The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

Chapter I: Introductory

Chapter II. The Amazons of Antiquity

Chapter III: The Amazons of

Antiquity--(continued)

Chapter IV: Amazons in Far Asia

Chapter V: Modern Amazons of the

Caucasus

Chapter VI: Amazons of Europe

Chapter VII: Amazons of Africa

Chapter VIII: Amazons of America

Chapter IX: The Amazon Stones

Chapter X: Conclusion

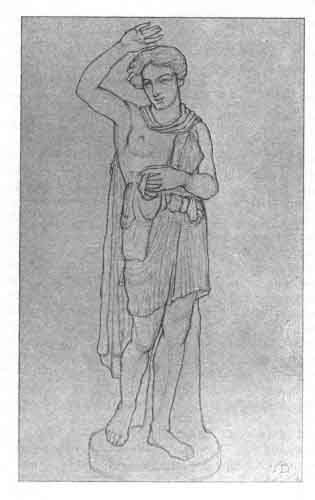

WOUNDED AMAZON. BERLIN MUSEUM, ATTRIBUTED TO POLYCLETUS, SCULPTOR.

NEVER, perhaps, has the alchemy of Greek genius been more potent than in the matter of the Amazonian myth. It has bestowed a charm on the whole amazing story which has been most prolific in its results; but, unfortunately, by tending to confine it to the narrow vistas of poetry, the intensely interesting psychological aspect has been somewhat obscured. Yet to us the chief value of this myth is due rather to the insight it affords into the mental workings of primitive races, the attitude of man towards that which he dreads but does not fully comprehend, than to the influence of Hellenic art and literature, fruitful in beautiful and humanising manifestations though that influence has been. The Greek spirit, indeed, working upon a crude collection of stories, took the sting, out of the lessons they should have taught. For, as we shall endeavour to show, the message of the myth to a people struggling towards a higher civilisation to beware of barbarians and their ways, was softened to an attitude of admiration before physical beauty and courage, and a tender pity for woman, fomenter of strife though she might be.

We may unhesitatingly sweep away the story of the unnatural state about which so many Greek poets and historians entertain us. But while relegating the Amazonian state to the realms of imagination, we must recognise the Amazon herself as a not insignificant historic fact--a fact, indeed, of sufficient moment to have peopled a whole world of fiction, real enough to its original creators, and whose force is hardly spent even now.

Etymology will not help us much, though it has been relied upon by controversialists. Any argument founded on the descriptive nature of the word, or on its somewhat suspicious many-sidedness, must prove a double-edged weapon, as likely to injure the wielder as his opponent. Besides the obvious "breastless" (a-mazon) and "moon" (maza), we are offered a choice of a variety of interpretations conveying to us such meanings as "vestals," "girdle-bearers," and other synonyms, also "game eaters" and "eaters of strong foods." But after all the word is hybrid Greek, not a native name, and may be classed as a nickname, itself much younger than the supposed state; and then, naturally, it would be as comprehensively descriptive as the ingenuity of man could devise. We may, therefore, leave the etymologists to the labyrinthine twistings of their own wordy warfare.

The tale begins rationally enough with the perfectly familiar incident in the life-history of so many nations, the expulsion of a surplus growth of population and its emigration to new fields. In this case we have reference to a cabal against two youthful Scythian princes, who, being ordered into exile, carry with them a whole horde of followers--men, women, and children. There is the story of their settling down, of their casting off of the old Scythian simplicity before a growing desire for riches, which leads to conquest and ultimately to their undoing--the men being mostly massacred by their enraged neighbours. Then comes the extraordinary violent rage of the widows and orphans, first against the slayers of their husbands and fathers, and later against men in general, this aversion bringing about the founding of a state that is to be manless, the women throwing aside their girdles, that priceless symbol of the unmarried, only for a brief spell in the spring-time, when by commerce with their male neighbours means should be taken to guard against the extinction of the race.

That such a myth should have sprung to life and gained credence is not difficult to understand. To the inhabitants of the Archipelago and Magna Grecia, no matter whence they originated, distant Asia and the regions to the north-east of the Black Sea and round about the Caspian were lands of peril shrouded in mystery, out of which fierce hordes swept down bent on rapine and conquest. Beyond the fringe of the nearer Mediterranean coast there were worlds of darkness, peopled by the fertile Greek mind with many unnatural but by no means illogically conceived monsters; for the makers of the myths had hardly emerged from the influence of animistic interpretation of nature. All phenomena were explainable in the terms of human emotions, and man acknowledged himself the relation, and not always the superior relation, of the beasts of the field, nay, even of the stocks and stones. To such men, nomadic tribes from the sandy Asian wastes bursting out of clouds of dust on their fleet horses to pillage and slaughter and then as swiftly pass away, had suggested the Centaur myth, the man-horses lying behind the woods ready to swoop down upon the unwary. The aborigines of forest districts, whose attacks were as dangerous and unexpected as that of the wild boar and wild goat, naturally suggested the satyrs. That yet older terror, the herds of wild buffaloes with their irresistible onrush and indomitable fierceness, had given birth to the superhumanly cunning winged man-bulls of Assyria. Successive waves of invasion rolling seaward from the north-east made utter Scythia a constant source of danger, and when the reflux waves carried the over-swollen coast population north-eastward, they entered an inhospitable country, where pitchy lakes and unctuous soil belched forth fire, smoke, and steam, an ominous presage of what might be expected beyond. Towering above stood a further barrier of rugged black mountains, inhabited by a race of savage warriors whose very women fought with all the ferocity of lionesses. This ever-menacing danger, with dim recollections of an outworn stage of development, when a matriarchal polity prevailed, and the nearer, more ghastly remembrance of the worship of cruel, sensual Astarte, that moon huntress goddess who came out of the Far East smeared with human gore, surrounded by her women priests, evolved in the brains of men whose thoughts were prone to take the dramatic form the idea of a truly monstrous state, the very existence of which was a perpetual threat against humanity. Indeed, the Amazonian state, with its population of women warriors, ruled by a queen who banished all men save a few crippled slaves, and banded together with the express purpose of making war upon mankind, perfectly symbolised the peril that Greece had to face. For the myth told not merely of war, but of unnatural war, war which if successful foredoomed family and civic life.

It is symbolic however we look upon it. A noteworthy fact is that certain legends made the Amazons worshippers of Artemis, while others declared them to be deadly enemies of that goddess and her followers. In art we find Amazons wearing the crescent moon on their heads; possibly, too, the triple-towered crown; while their shields were either crescent-shaped or round--these, with their spears and bows and arrows, are the emblems of the moon huntress goddess, both in the guise of savage Astarte and of her Hellenised, humanised counterpart, Artemis. It would be natural for a state whose people lived on the spoils of sport and warfare, who looked upon the sacrifice of male infants as a duty, who drank out of human skulls and were suspected of cannibalism, to worship Astarte, whose early history reeked of blood and was punctuated by mutilation, a deity who symbolised a stage of society when the hunting of wild beasts was of supreme importance. The apparent conflict between the various versions of the myth no doubt arose from a confusion brought about with the lapse of time between the two aspects of this goddess. In the early. forms of the legend it would be quite in accordance with their general trend to associate the warrior women with a female deity who, at all events in the degenerate days of her cult in Asia Minor, represented lust in excelsis. And here, it is likely enough, the myth was founded on solid fact, for it is well-nigh certain that the savage horde from Scythia paid homage to some prototype of Astarte. Her worship is undoubtedly of Eastern origin; this being so, one more reason would be added for the Greeks looking with mingled anxiety and abhorrence to the north-east. Among the several great cities of antiquity which were said to have been founded by queens leading successive swarms from the great parent hive of the Amazonian state was Ephesus. We know that its celebrated Temple to Diana (Artemis) was attended by eunuch priests and probably contained statues of Amazons due to the chisels of the foremost of Grecian sculptors. Though her servants cried aloud, "Great is Diana of the Ephesians," she was really a mild version of Astarte, tamed by the influence of Greek art and thought. Another significant fact is that in its earlier forms the myths of the Amazons and gryphons are represented as implacable enemies, and even in quite late art they are jumbled up with the wars of the centaurs and the gigantomachia, which points to the realms of fancy.

All this, of course, does not do away with the historic fact that out of those dark regions warrior women came, now as leaders, at other times in bands--both as camp-followers and in the fighting ranks. The phenomena, indeed, can hardly be said to be peculiar to any age or clime. Our own island history records the valour of Boadicea, queen of the Iceni, her sudden tempestuous appearance, leading in the slaughter of the Roman legionaries, the sacking of Roman camps and cities, and noble in her reverses. History and art tell us that the women of Germania and Gaul fought against the Romans. And such incidents repeat themselves again and again. In 1792 the French Revolution brought forth an Amazonian brigade, and it is not without interest to note in passing that a worthy French historian had years before claimed that the Franks were direct descendants of the Sarmatian Amazons. The eighteenth-century brigade comprised the gross dames de la Halle and the women of the Faubourg St. Antoine, who, their blood aflame with the lust of killing, decked themselves out, with some dim thought of classic times (that heroic age which fired the thought of a whole revolutionary generation), in short petticoats, red Phrygian caps, and carried most business-like pikes. Plutarch tells us of the valiant women of Argos who defended their city against the Spartans so well that they were allowed to dedicate a statue to Mars, and the women were thenceforth permitted to wear false beards on their nuptial day.

But as regards fighting, have we not that far more piquant incident of Thalestris appearing before Alexander as he was marching through Parthia, fresh from the conquest of Persia and the defeat of the Scythians? That a queen leading an army with a legion of women warriors did come to offer homage there is much reason to think possible, though the title "Queen of the Amazons" may be put down as a later embroidery of Greek historians. Plutarch, it is true, treats the whole story as a fiction, and quotes Lysimachus and Alexander himself in support of his contention. Against this we have circumstantial accounts of the invasion of Persia in the time of Cyrus by "barbarians" led by women. Rumours of warrior women are very persistent in further Asia, and the tradition culminates in the comic-opera squadron of 150 Amazons enrolled under Ranjeet Singh of Lahore. In the Caucasus travellers reported the existence of bands of fighting women down to comparatively recent times, but they were part of the community, not representatives of a female state. The fashion spread westward, for we find Amazonian bands in Bohemia during the eighth century, and we have tales of an attempt to establish a matriarchate among those turbulent people.

From Africa we have early tales of Amazons, partly, no doubt, founded on the real existence of great queens and their women guards, but largely coloured by the Greek myth. We have stories of Amazons to the south-east of Egypt and that other land of terrors, which Lady Lugard has so graphically described, a land to the south of the civilised portion, a country of the Nem-nems, or the Lem-lems, or the Rem-rems, or the Dem-dems, or the Gnem-gnems (for the savages always bore a repeat name, and do so down to these days), and those who wrote of them invariably added, "who eat men."

Curiously enough, Greek authors refer both to the African Amazons of the east and middle north, who are said to have overrun Asia, and also to a great Amazonian invasion coming from Ethiopia in the west. Some, indeed, would have us believe that these were descendants of the Scythian Amazons, who had wandered across the Mediterranean, passed through the Straits, and reached the Hesperides, whence they attacked Ethiopia, and, marching eastward, entered Egypt, crossed over to the Ionian Isles and Asia, to be finally overthrown by Hercules. It is a most curious story this eastward invasion, with its plausible account of an alliance with Horus, son of Isis, a sun goddess, consort and successor of that primeval moon and corn god and kin, the great, all-pervading Osiris, and herself identified with human sacrifice and mutilation, Now, the history of Africa north of the equator shows that there had been persistent penetrations from the east by a people of Asiatic origin coming through Arabia and westward by Africanised Asiatics, who, finding penetration from the Mediterranean shores slow, appear to have overrun the Atlantic coast and pushed eastward to blend with Nile infiltration. Did the fighting women come with the invaders, then truly descendants of the Amazons in the sense. that these dames of spear and buckler had fought for many centuries side by side with their trucculent men-kind? or did the civilised Egyptians and Berbers, advancing cautiously, ever struggling with the black bi-named eaters of men, find lands of armed maidens ready to dispute their way? If so, we have a spontaneous growth, later to be exaggerated by the declamatory. Greeks. Certain it is that we have early evidence of fighting bands of African women, perhaps the most famous of which are the eunuch-tended Congo and Dahomeyan Royal Guards, then the less definitely authenticated matriarchal countries of women-fighters on the eastward side, but no credible accounts of a woman-governed, manless state.

That America should possess its Amazons, not only armed cap-à-pie, but ruling over a man-free state, was inevitable. The fifteenth-century European was dominated by the Greek spirit. He went West, not to discover a new world, but to find a short cut to India, with its boundless wealth and all its wonders and monsters, as recorded by the ancients. Dreams of the lost Atlantis, the superb island-continent, the home of the Elysian fields, which had formed in imagination a mysterious and golden bridge between Africa and India, was a constant obsession to them. It accounted so conveniently for many problems and for so many of their plausible theories. Consequently, it is quite natural that the early explorers from all countries, but more especially those who had come into closer contact with and had received an intellectual stimulus from Arabic civilisation, should have seen things with a distorted vision, the result of preconceived ideas, unfailing credulity, and an abundant superstition. It is not necessary to disbelieve Francisco de Orellana's account of his meeting opposition from bands of armed women on the banks of the Marañon, and it was quite in the order of things that he should rename that river the Amazon, and straightway call forth from the vasty deep of his own credulity a state which was the exact counterpart of the Scythian Amazonia. That he and numerous other of his contemporaries had to make warfare on armed women may be accepted as fact; that they may have formed corps or "tribes" by themselves is possible. Native tradition itself is busy with tales of great queens and women leaders. We know that there were women priests, and in certain stages of evolution the priest is a leader and warrior. The elaborate tales of travellers who followed in the footsteps of the conquistadors, however, are suspect, both on account of their too close resemblance to Asiatic myths and because of the absence of corroboration in detail.

Of the historic Amazon little need be said for the moment. Under stress, human nature is very much to-day what it was yesterday and will be to-morrow; and woman, being woman, under stress is very apt to exaggerate human passions. It would be idle and tedious to labour the point which myth and history illustrate so well.

On the Greek humanising spirit we may dwell somewhat more at length. No graven or fictile representation of an Amazon approximately coeval with even the latest true myth-monger has come down to us. All the sculptures and decorated pottery we have belong to a comparatively late date, when the original abhorrence which had conjured up the myth was passing away. Literature, however, gives us some idea of the primitive view.

We are told of a turbulent, bloodthirsty race, cannibalistic, addicted to human sacrifice in their religious observances, sworn to repudiate the natural order of society, living only to make war on their neighbours, implacable in their hatreds. We see them disdaining Greek culture, rebels to the Greek demigods, overrunning Africa like demented Argonauts in search of a lieing belt (for never had symbolism been more audaciously misapplied than by the Amazonian assumption of the virginal girdle), laying siege to Athens, and only restrained from sacking Minerva's sacred city by the arts of diplomacy. It is a long story of rapine and robbery. Yet, even so early as the Homeric cycle of songs, the humanising spirit was at work. Achilles, called away from his duties to the dead Patroclus to stem the Trojan onslaught, is galled into Olympic anger by the vituperative and slaughter-dealing Amazonian queen and her captains, who had come to the aid of Priam merely to vent their rage against the Greeks. But in the very moment of his triumph, when victorious he is about to despoil the fallen queen, he is arrested by her physical beauty, and, admiring her warrior prowess, is seized with remorse that his hand should have delivered the death-blow to a woman. That the woman deserved her death, that she goaded Achilles to act in self-defence, does not alter the horror of the situation; for man feels himself in the wrong, no matter what the provocation. The pathos of such a situation called forth the best endeavours of art. The incident was dealt with at length by Arctinus of Miletus in his poem "Æthiopia," that continuation of the "Iliad," which his countrymen placed so high. It is an attitude towards the Amazons that is almost invariably found in Greek art. We have representations of their warfare with the gryphons and barbarians, their defeat by Hercules, their victories and repulses before Athens. We have them in groups and as single figures, not assuredly ideal female forms, for, although splendidly developed, and even in the vigorous postures of hand-to-hand combat, on foot or horseback, always graceful, there is a subtle suggestion in form and mien that is not quite feminine. The faces are generally strong, beautiful in outline, often tender in expression. There is, in fact, no hint of the virago in anything that the Greek sculptors have left for us, but there is that hint that these women were not as other women were. This is strictly in accordance with later Greek conception of the Amazons as a splendid race of women, sternly suppressing natural inclinations in the interests of their community and ideals. The rendering of such sentiments by artists is quite noticeable when we consider these sculptors in comparison with other examples of the Greek idealisation of the female form, whether it is a simpering Venus, a proud Diana, a majestic Athene, or, to come down to commoner clay, a laughing maiden and dignified matron. Now, if we further contrast this delicate suggestion of a difference founded on a natural deduction from the supposed ideal of the Amazon state with the violent representations of duality of personality as shown in Oriental art,--for instance, in the Arddhanarishwara,--we can the more clearly realise the refining influence of the Hellenic spirit. We can but pause in admiration at the sublimity of feeling and wondrous skill with which this is conveyed to the spectator. Yet, story for story, the ethical value of the Oriental is often far superior to that of the Occidental. But in the one case the spirituality is hidden, the representation of a beautiful thought is gross; in the other, on the contrary, it is sublimed. We may carry the comparison still further by contrasting the story of the rhackshasis-inhabited Ceylon, or the island of El Wak-Wak (which comes to us from India through Arabic sources), with the myth of the island of Ææa, where Circe dwelt surrounded by lovely handmaidens and her tamed wild beasts, bent, apparently, on much the same work as the Eastern women of inveigling men and then sacrificing them; but how poetically the cruelty underlying the lesson is softened. In the one case there is crude, vehement symbolism; in the other, much tender humanity. It is partly owing to the latter characteristic that when the Greek artists show men as opponents there may often be traced an underlying feeling of unwillingness. They are fighting to the death, but without hatred, though, of course, there are exceptions--such, for instance, as the two equestrian figures shown on a terra-cotta fragment in the Towneley Collection, where we see a beardless Greek youth bending forward on his rearing horse to seize with the left hand an Amazon by the hair, bending her head violently backwards; and as she falls, he lifts his right arm to strike her with a short sword. And there are many fierce combats in the larger relief sculptures.

As a rule, however, the artists seem bent on so telling the tale to the world that they may the more clearly impress the lesson they drew from the legends and from the hard struggles of life--"The pity of it, the pity of it!"

In the minor forms of art, the numismatic and fictile branches, we are as a rule a good deal closer in spirit, though by no means always in period of production, to the older versions of the legends. Because, of course, generally speaking, it is more popular art, which appealed to the oi-poloi. As regards numismatics of Hellenised countries, those tokens on which the apologists have relied so much in making out their case for the historical existence of the state, there is much that is extremely doubtful, a large number of the figures supposed to represent Amazons really being the geniuses of cities. There is, in fact, little to be gathered from them in this connection, either on the historic or the art side. In the pottery there is often a good deal that is rough, both in modelling and painting, and also in the matter of emotional expression. The crudeness is unquestionably due to its being popular art rather than to its age, for we find in many of the pieces a tendency to complication in design; the Amazons and Greeks do not fight face to face, but twist and turn about in elaborate evolutions, and this is often accompanied by a piling on of detail, thus getting away from the primitive types. But this pottery decoration is almost certainly imitative if not directly copyistic, too frequently falling to conscious caricature of the noble forms.

The legends, in any case, were favourite themes with the potters, who frequently show us the Amazons at their favourite trades of killing and maiming. The stories of Bellerophon, Hercules, Hippolyta, and Theseus are portrayed with endless variations, not without considerable vigour. A point to be noted is that in these paintings the Amazonian queens have the heads of Medusa on their round targets, though sometimes the gorgeion masks are seen on the Greek shields, betraying a certain confusion of ideas, or perhaps the different moral point of view of the artist. While the struggles are generally between the women and Greeks, we occasionally find Amazons assisting the Greeks in their fights against monsters, and the scenes between Achilles and Penthesilea are shown boldly and with some regard to sentiment. There is also a notable variation in the matter of costume, ranging from the short tunic or the chiton to the armour-clad female warriors with their Athenian helmets and crescent-shaped shields, and then to the Persian type of Amazon in close-fitting tunics and trousers, with Phrygian caps, which is often in startling contrast to the starkness of their adversaries.

Apart from the crudeness naturally associated with a large portion of this work, which was mainly mechanical, the designs being stamped on the clay over and over again, we find attempts to show both the fierceness and the physical beauty of the women.

CAPITOL MUSEUM, WOUNDED AMAZON.

When we come to consider the sculptures, even the earliest specimens extant, we must not forget that they belong to an age far removed from the myth-mongers, a full thousand years later than the legendary days of Amazonian strength and pride. In this branch almost always the scenes of Amazon combats--be the warriors triumphant in victory or imposing in death--appear to express the Achillean divine sorrow mingled with respect. We can see this even in what remains of the friezes from the Temple of Æsculapius now at the Central Museum, Athens, though these fragments of statuary represent wonderfully lifelike incidents of the fiercest fighting, where the artists have put forth their best efforts to make the spectators enter into the feeling of the veritable frenzy of energy which seems actually to be enacted before them. An Amazon wounded in the throat slips from the back of her fleeing horse; another, fallen to her knees, shows a magnificent head in the agony of death; while in the forefront an Amazon, very much mutilated, is shown astride of a rearing horse, holding her steed by a muscular grip on its panting flanks: she is lifting her right arm apparently to strike forward with her deadly spear. The head and greater part of the right arm are missing, but both breasts are indicated under the folds of the draperies. Every figure is instinct with the strenuousness of the battle, displaying the subtleness of the perfectly trained, combined with great beauty of outline. Much care is shown with the drapery. In the sculptures from the Temple of Apollo the Deliverer erected at Phigaleia in the Peloponnesus, and preserved at the British Museum, there is an equally wonderful gallery of figures of Amazons and Greeks in battle, those of the female warriors having an arresting charm both when exhibiting the vigour of the fighters and the exhaustion of the vanquished. There are in those worn but yet splendid marbles many touching incidents, as well as a good deal of hard fighting. The grouping is spirited, the figures being so arranged as to stand out boldly, giving full value to the moving representations of the hazards, hardships, and rush of battle. A wounded Amazon whose horse has stumbled, thus pitching her forward, has her right foot seized by a Greek intent on completing her downfall. Another mounted Amazon is dragged from her horse by the head. This pulling back of the head by the hair in order to upset the equilibrium or deliver a deadly thrust is shown in three or four other groups, witnessing the intensity of its struggle. On the other hand, the Achillean remorse is given prominence in several places, though on the opposite side. A wounded Greek is supported by an Amazon, who has her arm passed behind his shoulders as she leads him away from the strife; another kneels down to lift a wounded sister; and in a third instance a woman thrusts forward her arms to ward off the threatened stroke aimed by an Amazon against a fallen foe. It must be said that the chivalry appears to be all on the feminine side, but the point is that there is chivalry shown in a fair fight. The Greek artist has not attempted to belittle or defame the warrior women, whom he regards as foes worthy of Hellenic steel and who are to be respected. This temple was built by Iktinos, who was associated with Pheidias in the designing of the Parthenon, and from what Pliny says it is clear that leading Athenian sculptors were responsible for its embellishment, so here we have the true Greek feeling. In both these instances the costumes of the Amazons are quite primitive. The chiton is worn, stopping short well above the knee, caught at the waist by a girdle, and carried across the breast to be fastened over the left shoulder. The legs and feet are bare, a strap sometimes being shown over the right ankle to hold the spur. The helmet, when worn, is of the Minerva type. Great skill is displayed in managing the drapery, so that it shows off the fine bodily development and the exertion. Simplicity is the characteristic of all the accessaries, throwing into greater prominence the physical beauties. The sculptures, now also at the British Museum, from the tomb of Mausolus, Satrap of Caria, which his widow erected at Halicarnassus, belong to a somewhat later date, and, though inspired by the same feeling, show more licence and less refinement in treatment. There is a reminiscence of the older artists. The drapery is longer and ample; the chlamis, flowing from the shoulder, is added; but in the violence of action the figures are rather apt to be startlingly undraped. There are characteristic touches which take us back to the Scythian wilds: an Amazon fleeing on horseback has vaulted round, and, though astride, faces the pursuing enemies, against whom she aims a dart, the Parthian bolt. Here the strife is very pronounced and many of the actions fierce, but it is a fight among equals.

The two first groups belong to the supreme age of Greek art, when the influence of Pheidias, Polyclitus, and Praxiteles was at work. Of the great masters themselves we have no certain examples, though five celebrated marble statues of Amazons are almost indubitably copies of their original bronzes. All five have a strong family likeness. The Vatican Amazon has been attributed to Pheidias, and though in part badly restored, is a thing of priceless beauty. This youthful warrior has been recognised as a special type, differing not so much in general design but in treatment; unlike the others, she is not supposed to be wounded in her right side. She leans on her lance in the left hand; the right arm (which has been restored) is lifted above the head, the fingers lightly twined about the upper part of the lance. There can be little doubt that the hand should be grasping it, the whole poise of the figure showing that she is preparing to vault on to the back of her horse. The body shows vigour, though in actual repose prior to vaulting; the face is calm, and almost sweet in spite of the firmness of the outline. She wears a short chiton, caught up at the waist and fastened over the right shoulder, leaving part of the left thigh and the chest exposed. There is some sign of the a-mazon mutilation; otherwise, it is a model of youthful perfection, though in some respects it might be that of an Adonis.

The Capitoline Amazon shows even more tenderness, while true femininity is cleverly avoided. The head, however, is said to belong to another statue. The wounded girl, in her short chiton, the right leg slightly bent back from the knee, must have been represented as leaning on her lance with her right hand (but this has been restored so as to show it uplifted above the head), the left hand drawing the drapery away from her wounded side. There is no sign of the a-mazon mutilation in this statue; the right breast is exposed, but the left is expressed, though covered by drapery. The Berlin wounded Amazon has her right arm lifted above her head, as though instinctively raised from the sword-thrust in her side. She leans with her left arm on a column, her left leg is drawn back, contracted by pain; but, clear as is the evidence of anguish, there is no contortion of limb or features. The chiton is quite short, and there is little drapery over the upper part of the body; but the folds, which are elaborate, are at once decorative and natural. This statue has been attributed to Polyclitus, but is probably more justly claimed to be a copy of the original bronze, which may, according to the delightful story, have been the one set up in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus. It will be remembered that, according to a never-too-probable occurrence reported by Pliny, Pheidias, Polyclitus, Cresilas, and Phradmon, all competed for the honour of providing the ex veto Amazon, each being asked to make his vote for the best work. Each placed his own statue first and that of Polyclitus second, virtually a majority verdict for the latter. Though this story of competition has a certain air of reasonableness about it (for, according to very ancient tradition, Ephesus, whether or not originally founded by the Scythian women warriors, had given them refuge when hard pressed during their retreat after their dash into Attica), all that we can deduct from it is that statues of Amazons were shown in the temple. At all events, this tale of emulation among Greek sculptors to honour Artemis in her more tender moods as the Succourer illustrates the humanising spirit of their art, and would go to explain the undoubtedly striking similarity to the general design of the above three Amazons and, those of the Lansdowne and Vienna Collections. We are here, certainly, very far from the dreadful bloodthirsty woman of the primitive legend, or even from the boastful queen of the "Iliad."

The myth, forged in the dim past, when strife was dire and inevitable, had played its part. As outward pressure relaxed, and men became more enlightened, the story lost much of its grimness, but had not spent its power: the poet and artist made it their own, drawing from its grim details new meanings, refining its lessons to fit them for a happier stage of civilisation. And so they softened the story of Amazonian cruelty to serve their own ends, promoting the cult of the beautiful by holding up the splendid human figures, at once strong and graceful, to the emulation of maid and matron, and by calling for masculine admiration and pity.