The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER VI

AMAZONS OF EUROPE

IN order, on the one hand, to round off their stories of the break-up of the great Amazonian power, and on the other, to account for certain phenomena witnessed in various corners of the then known world, the Greek chroniclers put forward various plausible tales. While, as we have seen, they asserted that a galley-load or two of female prisoners, being conveyed to Greece after the battle of the Thermodon, revolted, and making their way beyond the Tanais, founded the Sarmatian-Amazon state, so, they held, the routed legions of Orithya, smarting under their defeat before Athens, and deciding never to return to Themyscira, wandered through Thrace into the wilds of Central Europe. Of these women there are many to claim descent. Indeed, Gilbert Charles le Gendre, Marquis de Saint Aubin-sur-Loire, writing in the early part of the eighteenth century in his Antiquités Française, declares that the Franks had sprung from the Thracian Amazons. Other sections of the lost legions are supposed to have lingered for many centuries in more or less autonomous colonies in various secluded corners.

Curious tales of these "women nations" crept up unexpectedly in popular lore. This was, no doubt, due to the Sarmatians and their customs, those descendants of the Sauromatœ of Herodotus and Pliny. In his Natural History Pliny says that beyond--that is, to the north-east of--the river Tanais, there dwelt the Sauromatœ Gynœcocratumeni ("the Sauromatœ ruled over by women"). This would seem to point to a matriarchal form of government rather than to the old Amazonian manless state, and was, in fact, an elaboration of Herodotus, whose account of the Sauromatœ we have already given at some length. It will be remembered that this nation was said to be a colony founded by part of the Amazons whom Hercules had dispatched towards Greece, but who, all too insecurely guarded, had risen in revolt and directed their galleys to the Black Sea coast. The rule of a queen was quite within the laws of the old Slav race, and we have in Pliny's story little more than a confusion between a queen's dominions and a mythical matriarchate. We may even take note of the views of some authorities who hold that the "ruled over by women" must not be taken too literally, but rather be regarded in the light of a descriptive jibe addressed by neighbouring women-enslaving races against the Sarmatians, who admitted women to share their most prized privileges, sports and warfare.

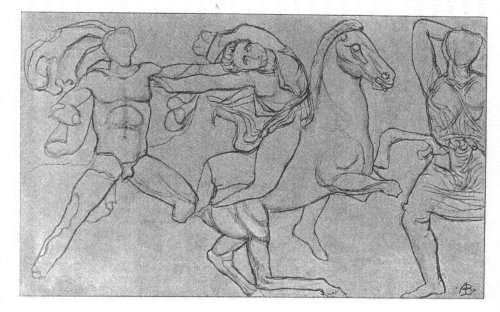

SECTION OF PHIGALEIAN FRIEZE, COMBAT OF GREEKS AND AMAZONS. BRITISH MUSEUM.

The geography of this region is very confused, not only because the boundary between Europe and Asia has been a constantly shifting line, but owing to the still more bewildering fact of natural topographical transformations. Inland seas have shrunk, rivers changed their courses, swamps dried up. As for the Tanais, it was regarded as the boundary between Europe and Asia, and has been identified with the Don, which river rises in Lake Ivan Ozero, in the far government of Tula, flows south-east, then south-west, and so into the Sea of Azof (the old Palus Mæotis, once far more eastward than it is now). Some geographers have identified the Tanais with the Donetz, which flows south-east from a little above Karkof and joins the Don not far above the Sea of Azof, but this seems quite improbable. As regards the Sarmatians, it is clear that they migrated westward, being the first Slavs to spread over Russia, Poland, and Bohemia, and this accounts for much in the survival of both legends and habits.

As late as the eighteenth century we hear of women communities in Russia: indirectly from George, Lord Macartney, who went on a delicate mission as British Ambassador to St. Petersburg between the years 1765 and 1767. Writing upon the subject of the Cossacks, he refers to those of Zaporavia, who, he says, were 30,000 strong, and "consist of persons of all nations, and live in a singular sort of society, to which no woman is admitted. They are a sort of male Amazons, who, at a particular season of the year, resort to a certain island of the Dnieper, and in the neighbourhood, where they rendezvous with the women dependent upon them." He says their customs were those of the most primitive savagery. The girls remained with their mothers, but the boys, on reaching a suitable age, accompanied the men, to be trained as hunters and warriors. This arrangement, however, was far more natural under the circumstances than appeared to the worthy Irishman, whose details as to the mode of life and excesses need not be taken too seriously, for they appear to be the usual gloss placed by superior ignorance on exceptional customs only partially understood. What stands out clearly enough is that these men, under the service which they owed to the Government, had perforce to lead a nomadic life, and the organisation of these warrior bands compelled them, while away patrolling vast stretches of country, busy training and hunting, to leave their womenkind in village camps. No doubt a river island would be chosen as a place of some safety, having a natural protection, and this would give rise to the wild legends. However, the student will find the passage in all its crudeness given in Some Account of the Life of Earl Macartney, edited by Sir J. Barlow.

As we have said, rumours of such colonies spread far afield. Long before Lord Macartney had penned his description of the Zaporavian Cossacks, Adamus Bremensis, writing in the sixteenth century, declared that there existed an island peopled by women only, lying off the Baltic shores. It is true, however, that this is generally said to be an error of the learned and pious historian, who confused the term Gwenland (Finland) with the land of gwens (the land of women).

That women in Europe as elsewhere took up arms in defence of their homes against external oppression, or during internecine disorders, there are endless instances to prove, from the days of Roman expansion down to our own times. With us in England, there have been many notable women leaders, and not a few examples of women banding together for warlike purposes, though sometimes without bloodthirstiness. One such case may be classed with the innocent stratagem of the Quaker, not he who trusted in Providence and kept his powder dry, but that other, who, more fundamentally pacific, indulged in dummy wooden cannon, only formidable to look upon. When the French, under the inspiration of the "Corsican Ogre," made their forlorn attempts to invade these islands, turning their attention to the west, Ireland and Wales, our countrywomen aided and abetted our men volunteers in many defensive ways. At Fishguard a notable feint was adopted on the approach of the enemy, the women banding together, with red shawls about their shoulders, marched about and massed in solid battalions on the green hillsides, so that the French general was deceived into believing that large bodies of reinforcements were at hand, with the result that the landing was not pressed. Local tradition has it that one of the red-shawled women, Jemima Nicholas, whose modest tombstone is still to be seen in the churchyard, actually managed to corner and deliver to the authorities seven French soldiers.

So naturally do particular needs bring about similar results that we find a parallel to this in Spanish history during the heroic period of the Gothic struggle against the Moorish invasion. One of the leaders, beaten back from the coast to his fortified town of Tadmir, found his fighting ranks so seriously depleted by the sword that he caused the women to don male attire, tie their hair under their chins to represent whiskers and beards, take up arms, and form a background to the actual fighters.

Thus strengthened he was able to present a redoubtable front to the Moslem and thereby exact honourable terms, which were scrupulously observed, in spite of the deception.

The true fighting spirit appears to have always been strong within the Spanish women's breasts. During the War of Succession, Barcelona was long defended largely by its women, though it ultimately fell to Marshal Berwick. Then during the Napoleonic campaign, when Saragossa was attacked by Marshal Lefrebre, there were only 120 soldiers and a few old guns to defend its 12-feet high ramparts. So the women formed themselves into companies of 200 and 300 strong, relieving the men and fighting side by side with them. Lefrebre could make no impression until he succeeded by means of bribery in having the powder magazine blown up. Then he rushed in with his troops, taking advantage of the dismay and disorganisation; but one of the maids, Agostina, seizing a lighted match, discharged a cannon at the serried ranks of the invaders, and rallying the town garrison, expelled the French, keeping them at a distance until the British came hurrying to the rescue. Agostina begged to be allowed to retain her rank as an artilleryman. She was awarded a pension and the honour of bearing the name and arms of Saragossa. On the Ligurian coast we hear of many equally brave actions on the part of women in keeping the Saracens at bay. A later incident, when the Niçois came into conflict with the Barbaresco pirates, is worthy of note. It occurred as late as 1527, when Catherine Sigurana was the means of repulsing Barbarossa from the citadel of Nice. Barbarossa, Bey of Tunis, was the vassal of Suliman II., the abhorrent ally of the shameless Francis I. of France. Sigurana was a patriotic virago of a type different to Penthesilea, for she was nicknamed Maufacia, which tells its own sad tale. But, indeed, every country in Europe had its fighting women and its individual feminine warriors, even the spirit of aggression having been kindled among crowds of them, as in the abortive prelude to the first Crusade, when Peter the Hermit led his contingent of 40,000 men, women, and children to destruction.

Not one of these well-known warlike acts of women, mainly in defence of their homes, was associated with any form of, or claim to, women rule. There is, however, one episode in European history which does stand out with peculiar prominence in spite of its semi-fabulous embellishments; and there is a second semi-Amazonian passage which is only too authentic.

Bohemia, the Boiemum of Tacitus, originally formed part of the vast Hercynian forest. It is an elevated plateau, practically surrounded by a chain of high and grim mountains, whose spurs jut out into the plain, and is traversed by many rivers, including the romantic Elbe. Here the Borii, a Celtic people, dwelt before the advent of the Marcomani, who in turn gave place to the Slavs, themselves of the Sarmatian stock, and, therefore, presumably connected with tribes having Amazonian tendencies. These Slavs of Bohemia were ruled over by elected chiefs, the last of whom was Crocus, or Krok, who had a daughter named Libussa.

Æneas Silvius, in his Historia Boëmii, says that Libussa succeeded her father, and calling many women to high office, trained her sex assiduously in military exercises before leading them to numerous victories. On her death there were those in the kingdom who desired to bring about a change in this state of affairs, which caused a revolt of the women, headed by Valasca, or Dlasta, one of Libussa's favourite henchwomen. Valasca seized the reins of government, placing women in all offices. She ordained that only women should be trained to the art of warfare. The better to ensure this end, while the girls were to receive a specialised military education, the boys were to be so treated as to render this impossible, their right eye and their thumbs being removed, making the handling of weapons in a fight out of the question--a piece of cruelty which betrayed the inherent weakness of her schemes and cause. Valasca is said to have reigned for seven strenuous years, and then on her demise the business of the nation resumed its normal course. Great ruins on Mount Vidovole, known as the Divin-hrad ("The Virgin's City"), were long pointed out as the reputed headquarters of Valasca.

That these experiments in high statecraft were not without a patriotic basis, and tended to foster national pride, is proved by the fact that the old folk-songs are full of allusion to valiant deeds of these two heroines. These time-worn fragments of pagan civilisation are intensely interesting, for they show that the whole mode of thought of the people tended to self-glorification, the whole tribe forming one large family, and their outlook on the world was animistic. Nature was in close sympathy with the chosen people. A squabble among petty chiefs over land questions sufficed to cause the rivers to overflow and the mountains to quake. It was on such a nation that Libussa and Valasca tried their powers. But, as is the way with minstrelsy, the deeds of the good women and the effects that they produced were somewhat exaggerated. The truth seems to be that Libussa, the youngest of three daughters, was born in 680, succeeded her father in 700, and died in 738, leaving heirs. It was strictly within the primitive Slav habits that a younger child, if possessing special qualifications, should succeed to family property and headship; for, with sound common sense, primogeniture was not recognised, practical experience so constantly demonstrating the first-born as deficient, mentally and physically. Libussa, who was reported to possess the gift of prophecy, called to her assistance her two sisters, Kaça and Teta, and also instituted for her support a Council of Virgins. Among other of her works was the establishment of the Three Orders, or Estates, partly as a barrier against the pretensions of the nobles, and partly to maintain the old laws, for the Orders acted as Courts of justice. She married Przemyl, a peasant, founded the city of Prague, and wherever possible employed women to fill responsible posts. At her death, however, the Council of Virgins was abolished. Thereupon Valasca, Libussa's chief confidante, rose, and gathering the discontented about her, attempted to found a women's state; but her triumph was only partial and shortlived. One can well imagine that the edicts issued by a select committee of "young persons" must have been decidedly irksome to the staunch men of the somewhat turbulent and much-threatened land, so that the overthrow of the feminine influence set up by Libussa cannot be a subject for much wonderment. Still, Bohemia, even in her days, was very far from being an Amazonia. Libussa herself married and left a posterity which was represented in the proud house of the Hapsburgs, whose last descendant in the direct line, Maria Theresa, played so important a part in Europe, and did so much for her country. That the old folk-songs and traditions have in the main transmitted faithfully enough certain extreme proposals of the irate Valasca (ironic Fate's caricature of her worthy mistress) is probable. However, as, apparently, the majority of the men preserved their right eye and their thumbs, they could afford, after the heat of the struggle, to sing only of the glorious achievements of the safely dead heroines.

The second series of episodes do not reflect much honour on humanity, or rather, carry us back to the primitive stage of the Greek mythus, though certain mitigating circumstances have to be taken into consideration. Quite early in the days of the first French Revolution the women, especially those of Paris, assumed an active share in political affairs, and rarely, it must be confessed, took sides in the interests of peace or goodwill. But, as Michelet truly observes, the women had for centuries borne the brunt of double suffering, for they partook of the miseries of those they loved as well as of their own. They were driven to desperation by a long and heavy accumulation of wrongs, which seemed to have no ending. They had taken part in the capture of the Bastille, and had witnessed attempts at reaction, tolerated if not encouraged by the Royal Family, and fostered by the Court ladies.

Maddened by tales of how the national tricolour cockade had been trampled underfoot by the courtiers in the presence of the king and queen, and replaced by the "anti-patriotic" black or white bunch of ribbons, that momentous march on Versailles was decided on. A young girl at the Central Markets had seized a drum and beaten the general assembly, and as the crowd of women poured forth they were met by others from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and contingents of yet others who had been harangued in the Palais Royal by a young lady. Another woman, the already notorious actress, Theroigne de Mericourt, surnamed "the Amazon of Liege," grasping a lighted match, got astride of a cannon, and was dragged along thus in the hurly-burly of that curious procession, half friendly, half ferocious, almost wholly demented, wending its weary way to aristocratic and unspeakably profligate Versailles. The women would not be denied, and they, more than the men, were instrumental in bringing king and queen, dauphin and the rest, back to the Tuileries, that gigantic stride towards the tragic end. Early in 1792 the Municipality of Paris had decided that all sansculottes should be armed with pikes, and in August of that year the National Assembly decreed that the ordinance should apply to every citizen; whereupon the women claimed that they too came under the law. It was in the spirit of the "Declaration of the Rights of Women," issued by Olympe de Gonges as a counterpoise of the Contrat Social of Jean Jacques Rousseau and the "Declaration of the Rights of Man," in which she declared, "Woman is born free and with equal rights with man. Woman has the right to mount the scaffold: she must also have the right to mount the platform of the orator."

At last the market-women, those robust Dames de la Halle, and their sisters of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, formed themselves into an Amazonian brigade, imposing on themselves the duty of guarding the prisoners, escorting the dismal tomberaux to the guillotine on the Place de la Révolution. Their uniform was a short skirt, striped blue, white, and red; sabots covered their feet; and they wore the red Phrygian cap (the "Cap of Liberty," formally adopted as a badge by the Jacobins in 1792), adorned with a huge tricolour cockade. Each woman had a baldric slung across her shoulder, supporting a cutlass, and carried the democratic pike. It was an ugly band, often engaged in uglier work. Theroigne de Mericourt and Rose Lacombe had come to the fore in most of these events. Theroigne, indeed, was placed in command of the third corps of the army of the Faubourg, and went about dressed in a red riding-habit, huge hat and plume of feathers, and carrying a sword of honour that had been presented to her. Another warrior, the opera-singer, la Maillard, who had represented the Goddess of Freedom at the Feast of Reason, adopted a different outward manifestation of "the rights of women," donning male attire, fighting duels, and, assisted by other similarly attired women, went about Paris endeavouring to

compel every maid and matron to follow suit.1 All these women came to grief. Theroigne, suspected of being a Girondist by the Amazons, was seized on the Terrace of the Tuileries, stripped naked, and whipped like a naughty child by her erstwhile companions in arms, amidst the hilarious jeers of the populace. She became a raving lunatic, and died in Bicétre as late as 1817. Rose Lacombe came to her undoing through love: trying to save an aristocrat, she fell into disgrace; but, although toppled from her dizzy position as popular favourite, she was luckier than her companion leader, dying in peace long after the revolutionary fury had run its course. Olympe de Gonges, having irritated Robespierre by her pretensions and irresponsibility, was condemned to die; and though she pleaded approaching maternity, a jury of matrons consigned her to the guillotine; while la Maillard, by her endeavour to force her sisters into pantaloons, raised such a tumult that she hurried the Committee of Public Safety into issuing a decree that women should take no part in government, and that all their Clubs where politics were discussed should be closed.

Less shocking to human feelings, though equally warlike in spirit, were the armed battalions of women and girls formed in the provinces, especially in the Dauphiné, who were sworn to defend the country and democracy. They were also active in the clubs and political circles; and on the other hand, the women of the Royalist or reactionary side entered the militant ranks: there were various leaders and individual fighters, though few instances of their banding together in companies. But the feminine ambition of the French women in those days was to share work and responsibilities, not to usurp independent power.

Footnotes

107:1 Similar sartorial eccentricities have shown themselves in our days. There are followers of la Maillard and also of Theroigne, for the colour manifestation is showing itself among the "advanced" women of Finland. Mr. Paul Waineman says: "Red is now the recognised hue for women socialists. This is carried to such an extent that the female socialist members of the Diet wear bright scarlet gowns when sitting in the House."

Next: Chapter VII: Amazons of Africa