The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER VII

AMAZONS OF AFRICA

DIODORUS SICULUS, quoting Dionysius the historian, says that there was a prodigious race of Amazons who rose, flourished exceedingly, and disappeared long before the Trojan War--so long before, indeed, that their renown had been obscured by the newer glory of the Amazons of the Pontus. The more ancient race had its origin in Libya, that Africa which lay between Egypt and Ethiopia on the east, the Atlantic on the west, bounded on the north by the classic strip of Mediterranean shore, and on the south by the imaginary Oceanus River, a land harbouring many curious things and peoples. These regions, according to "ancient histories," unfortunately not cited, were at one time famed for their "warlike women of great force." Among these were the Gorgons, who dared to make war on the gods and the Greeks, and against whom Perseus, that prince of high virtue, son of Jupiter and foremost of Grecians of his day, fought under many difficulties and at much hazard to himself, so terrible were the women's valour and might. From which whole-hearted acceptance of the gorgonomachia we have fair warning to be cautious of these "ancient histories." Diodorus, it is interesting to note, writes of the Gorgons as of a numerous tribe or nation, rather than as the classic trio of sisters whom the gentle-eyed Pallas Athene and the aristocratic Perseus treated so scurvily. Certain it is that viragoes of the Gorgon type, setting divine and human law at defiance, have constantly made their appearance hereabout and a little to the southward. However, leaving this subject of inquiry aside, we find our authors stating that it was on the western limits. of this land of strange things, "towards the uttermost parts of the earth," that the Amazons first sprang to fame. There they "led another manner of life than our women do, for they used to exercise themselves in feats of arms until a certain time for the conservation of their virginity, and after that was expired they married to have children. They alone held the dominion and commanded, administering all public offices and affairs, and their men, after the fashion of women, had in charge the private business of the house, obeying their wives, and utterly ignorant of matters of war and the government of the commonwealth." We have here, in this special form of marriage, a radical departure from the Themysciran policy, and one all the more striking as it coincides in a most remarkable manner with what is reported of African Amazons within historic times, as we shall have occasion to relate in connection with the eastern and western regions. In other particulars--in war training, suppression of the right breast, and special reliance on horse-craft--the African and Asiatic customs largely agreed.

As regards the first seat of their government, a most interesting question arises. Diodorus says that they lived on the island Hisperia, otherwise Tritonia, so called because it was situated in a fen called Tritonida from a river of that name which entered the ocean. The fen lay between Ethiopia and the Atlas. It is generally assumed that by this the Hesperides, or Fortunate Isles (or the modern Canaries), is intended, and this conjecture seems to be confirmed by the statement that Tritonia was a country subject to earthquakes and where, as it did in the Asiatic cradle of the Amazon race, flames belched forth from the ground. But the description given by our author appears rather to apply to an oasis in a marsh, or perhaps the Great Sahara, or an island detached from an alluvial delta. It is remarkable that it is placed like a wedge between the Atlas range and the land of the black men. Such-like spots have, we know, at various times formed refuges for races of a different kind to the blacks, where local civilisations were developed, and whence these higher races sallied forth to conquer with fire and sword. We are also told that Tritonia was ultimately submerged, being swallowed up by the sea after a tremendous earthquake, a statement which inclined many to identify the African Amazonia with the lost Atlantis, though that would certainly not tally with the other curious topographical details given by Diodorus.

Our Sicilian historian goes on to say that the Amazons soon conquered the whole of the island, with the exception of Mene, the sacred city of the "fish-eaters." They wore no armour, clothing themselves in the skins of snakes, which approximates these women to witch doctors or priestesses of some form of sun worship, for snakes are connected with magic and the sun. Down to these days snakes are among the most treasured fetishes of the natives of this part of the country, and another sun animal, the crocodile, was associated with the modern royal Amazons of Dahomey. The ancient ones had for arms the bow and arrow and the sword. Thus they are clearly differentiated in religion and war panoply from the Themysciran Amazons. In Africa, as in Asia, the lust of conquest proved irresistible. Queen Merina, assembling an army of 30,000 infantry women and 2000 horse, entered the Land of the Blacks, attacking the Atlantides, capturing their chief towns, and putting every man to the sword. This politic rigour had the desired effect: the whole country submitted to the yoke of the Amazons, who placed the men under vassalage to be ruled over by women governors, and recruited fresh warriors from among the strongest of their own sex. Apparently while Merina was away, Hercules, coming west, had marked the extreme limits of his conquests by erecting his Pillars (the triumphal and thanksgiving1 columnos usually built as symbols of possession) on the twin rocks of Calpe and Abyla, where the Iberian peninsula most nearly touches the African coast, passed over to the Hesperides, attacked the Amazons, destroying their power in the west, as he had attempted to do in the east. Other writers say that Hercules delivered his crushing blow to the strength of the Libyan Amazons either in the Ionian Isles or in Egypt.

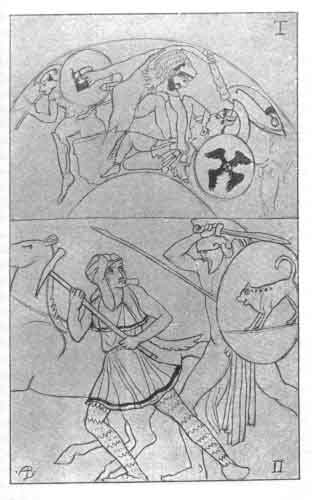

I.--COMBAT OF HERCULES AND AMAZONS.

KYLIX. BRITISH MUSEUM.

II.-ACHILLES SLAYING PENTHESILEIA.

AMPHERA (WINE JAR), BRITISH MUSEUM.

Of Merina we are told that she marched across Africa with her great army, and passing through Ethiopia, came into Egypt, there entering into a league with Horus, a sun god and son of the moon gods, Osiris and Isis. Strengthened by such an alliance, she subdued the Arabs, conquered Syria, and receiving the submission of the Cilicians, passed through Phrygia to the Mediterranean. Towns were founded and colonies also planted as the triumphant march progressed. The Mediterranean offered no obstacle to the conquering host: Lesbos and other islands fell to the Amazons. Cast ashore on Samos after a terrific storm, one of those sudden furies to which that sea is so liable, they erected a temple in accordance with a vow taken in the hour of peril. Exhausted by their long warfare, the Amazons succumbed to the fierce attacks of large Greek and Greecised armies led by Mompsus the Thracian and Sypylus the Scythian, and on the death of Merina the African Amazons ceased to exist as a nation. So far Diodorus. Other writers incline to the idea of an eastern invasion of Libya. They say that Egypt was overrun by the Scythian Amazons, as it undoubtedly had been invaded before by various martial Asiatics, and was subsequently to be by the Persians. Of these Amazons some are said to have returned to the Greek isles, some wandered westward across Africa to the Atlantic. A third version is that on the break-up of the Themysciran power certain Amazons made their way from Sarmatia through Gaul and Iberia to the Atlantic, where they put to sea and captured the Hesperides, returning east across the continent to Egypt.

It is a remarkable fact that the history of Northern Africa presents a record of constant penetration by waves of conquest from the east, now by way of Egypt, and again by white or brown tribes dribbling through the mountainous ranges cutting off the Mediterranean coast fringe, or entering by way of the west. There is a recurring story of white or brown races pushing back the black people and driving a wedge right across the continent, which was rendered possible by the physical character of the country. Lady Lugard describes very fully a trans-continental belt which afforded a vulnerable point in the natural defences of Libya and Ethiopia. First there is the historic Mediterranean coast strip from the Nile to Cape Spartel, then a barrier of grim mountains, but usually with a fairly fertile southern slope, jutting out like feelers into the dreary sandy wastes of the deserts, which stretch right across between latitudes 10° and 15°. Next we have the waterways of the Nile, the Bahr-el-Gazel, the lakes and rivers of Darfour and Wadai, the Shari, Lake Chad, the rivers of Hausaland--the Benne, the Niger, and the Senegal. This chain offers at once a barrier against the southern advance of the sands and provides a fertile subtropical belt, comprising Black Land--the Soudan, Ethiopia, Nigreta, Tekrour, Genowah, in some parts peopled with races of very mixed blood. North of the waterways is the sand ocean, which, in spite of its changing surface, retains a deadly monotony; south of it are in many places dense and gloomy forests, regions inhabited by giants, pigmies, cannibals, and beasts of strange forms. Against all these the white and brown invaders had to battle, a struggle which has left a deep impression on tradition and literature, and not least on the people. That ancient historians knew something of these regions is evident from their descriptions of Ethiopia and Libya, with their natural boundaries of seas, sandy plains, and the, strictly speaking, nonexistent but fairly well represented river Oceanus. And then there is the Semitic and Asiatic invasion, both direct by way of the Nile and south-westward through the Atlas ranges. It is the echoes of such emigrations that we have in Diodorus's account of the eastward march of the Libyan Amazons.

Herodotus, writing of the Libyan tribes, refers to the Zavecians, "whose wives drive their chariots to battle," a custom which must have been introduced into Northern Africa from Asia through Syria.

Philology is also not without its interest in this matter. Mr. J. C. Prichard, quoting M. Venture, says that the Berbers (of unquestioned Asiatic origin) inhabiting the Northern Atlas call their language Amazigh, which has been translated as "the noble language." There have been some authors who trace the word Amazon from this term. However that may be, it is certain that these tribes of Northern Africa have bred many valiant fighting women. When in the seventy-seventh year of Hegira the Moslems under Hossan Ibn Annoman captured Carthage and sent the Imperial troops packing in hot haste to Constantinople, they suddenly found themselves confronted by a more formidable enemy. This was a native queen, Dhabba, whom the Arabs called Cahina or "The Sorceress." She was regarded as a saint and magician by her people, and had contrived to enlist under her banner the wild Moors from Mauritania and the Berbers from the verge of the desert and the fastnesses of the Atlas range, also receiving active support from the civilised dwellers of the flat coast strip and its many wealthy walled towns. Dhabba proved victorious, and caused Hossan and his Moslem host to retire to Egypt. But after all she was a barbarian, and her patriotism took a barbaric turn. Pointing out that the followers of Mahomet were attracted to their country by the rich towns, the beautiful gardens with their groves of fruit trees, she advised her troops to dismantle the town walls, to pull down majestic buildings, uproot the prolific gardens, and hew down the fruit orchards. The nomads from the desert, the semi-troglodytes from mountain ranges were nothing loth, and the whole country was quickly converted into a howling wilderness. It was a costly mistake, for thereby the numerous and powerful seaboard population was rendered hostile, and when Hossan returned with greater forces, he found the queen's legions thinned and the coastal people anxious to welcome him. Dhabba, in spite of her bravery, was defeated, and, refusing to submit, was beheaded.

Returning to the Upper Nile, we find Sir George Rawlinson stating that in his days the king of the Behrs on the White Nile had a guard of women, who protected him so effectually that no man could approach his person except his ministers, who came to strangle him when he was nearing his end--a gentle attention designed to prevent his departing this world as a mere common disease-ridden mortal. But we may well ask whether this guard and the gruesome custom had not a profounder meaning. We are tempted to see in the petty sovereign a representative of a once god-king, whose duty and high privilege it was to offer his life as a sacrifice for the good of his people, he himself merely hastening his journey, and then these guards would be recognised as successors to priestesses. Certainly the conjunction of attendants and custom is suggestive of Asiatic practices. As late as 1840, M. d'Arnaud found the king of the Behrs surrounded by a body of spearswomen.

It was somewhere in this neighbourhood that Father Alvares gathered information concerning an Amazonian nation differing widely from the classical type. The father accompanied the Portuguese Ambassador to the Court of Prester John, Emperor of Abyssinia in 1520-1527, and in his quaintly straightforward narrative of the mission he gives an account of the tributary kingdoms of Damute and Gorage, which lay to the south-west of Prester John's territories. After this he adds: "They say that at the extremity of these kingdoms of Damute and Gorage, towards the south, is what may be called the kingdom of the Amazons; but not so,--as it seems to me, or as it has been told to me, or as the book of Infante Don Pedro related or relates to us,--because these Amazons (if these are so) all have husbands generally throughout the year, and always at all times with them, and pass; their life with their husbands. They have not a king, but have a queen. She is not married, nor has she any special husband, but withal does not omit having sons and daughters, and her daughter is the heir to the kingdom. They say that they are women of a very warlike disposition, and they fight riding on certain animals, light, strong, and agile, like cows, and are great archers; and when they are little they dry up the left breast, in order not to impede drawing the arrow. They also say that there is very much gold in this kingdom of the Amazons, and that it comes from this country to the kingdom of Damute, and so it goes to many parts. They say that the husbands of these women are not warriors, and that their wives dispense them from it. They say that a great river has its source in the kingdom of Damute, and opposite to the Nile, because each one goes in its own direction, the Nile to Egypt: of this other no one in the country knows where it goes to, only it is presumed that it goes to Manicuigo." Here we have sufficient details of what appears to have been a matriarchal state, peculiar in this, that the women were trained as warriors, but not Amazonian as described at Themyscira, though the drying-up of one breast is certainly suggestive of the Asiatic practice. But it is the account of a complete community, like that of the Sauromatœ Gynœcocratumeni, merely with the special social functions reversed; thus it does not fall into the same class as the Grecian myth of the unnatural state, which no doubt explains the cautious hesitation of the, reverend chronicler.

Father Jaos dos Santos, who had preceded Alvares, visiting Abyssinia as a missionary in 1506, says: "In the neighbourhood of Damute is a province in which the women are so much addicted to war and hunting that they constantly go armed. When contention fails in their neighbourhood they purposely excite quarrels among themselves, that they may exercise their skill and courage, and neither the one be injured nor the other relaxed by idleness. They are much more daring than the men of the country, and that they may have no impediment to the proper exercise of their right arm, they are accustomed, while their daughters are young, to scar the breast of that side with a hot iron, and thus wither it to prevent growth. Most of the women are more occupied with warfare than the management of their domestic affairs, whence they rarely marry, and live as formerly did the Amazons of Themyscira. Where by chance any enter the marriage state and have children, they take charge of them no longer than till they are weaned, after which they send them to their fathers to be brought up. But the chief of them imitate the example of their queen, who lives in a state of perpetual virginity, and is regarded as a deity by her subjects--nay, even all the sovereigns whose territories are adjacent to hers pride themselves on living with her on friendly terms, and defend her against any attack. Indeed, the power of this monarch is such as to make her another Queen of Sheba, whose authority over her subjects, as is related by the Patriarch Bermudes in his book on Prester John, was without limit. The same patriarch relates that off the coast of China islands are found peopled with Amazons who suffer no man among them except at certain seasons, for the preservation of the race."

This mention of Chinese islands reminds us that Socotra was also said to be an Amazon island, while others declare that the dual Male and Female islands, wherein, as Marco Polo describes, the sexes lived apart with only periodical visits, lay off Socotra. Thomas Wright, in a note on Marco Polo's travels, refers to two different maps whereon these islets were marked respectively as "Les Deux Frères" and "Les Deux Sœurs." This, however, might well have been in allusion to their nearness and similarity of outline. The naming of localities by discoverers is generally determined on a very lax system, and therefore proves a dangerous guide for shaping any theories. For instance, we know that William Baffin during his explorations in the Arctic regions in 1616 named an islet Women Island because they first met women there after several months of isolation, yet he says that men were with them. So it comes about that much of the nomenclature of new-found lands is misleading, because it is determined by accidents often of a trivial nature.

As for Father dos Santos, his reference to the quarrelsomeness of the women may be put down to professional zeal; but his remarks about the queen are most instructive. Her condition of life was certainly not that attributed to the Asiatic Amazon sovereigns, and seems to have reference to a sacred priest-queen, whose life was a consecration, if not a sacrifice. The alleged attitude of the neighbouring chiefs, who desired to be on friendly terms with her and deemed it an honour to defend her dominions, rather confirms this view. Father Alvares paints a less pleasing picture, but one closer to classic examples. On the other hand, the lapse of some twenty years between the two accounts may well have brought about changes, notably in the dignity of the ruler. Another Portuguese priest, the celebrated Don Jao Bermudes, patriarch and presbyter, who was sent on a religious mission to Prester John's country, rather tends to confirm the version of dos Santos, for he too, in describing the province of women near Damute, says that "the queen of these women knoweth no man, and for that act is worshipped among them as a goddess." This worthy patriarch categorically avers that the nation owed its origin to the Queen of Sheba. But he was fond of dogmatic statements, somewhat greedy of marvels, so much so that his lively accounts of various animals--among others, vultures which could lift and fly away with buffaloes--drew down a scathing rebuke from the industrious Samuel Purchas, the famous collector and translator of voyages; then this worthy editor, having cried out against the fables and the fabulists, adds, with the true note of the philosophy of doubt: "And yet may Africa have a prerogative in rarities, and some seeming incredulities be true," a fact which we of this generation have proved in more than one connection, though not in all, that has been said of the mysteries of the Dark Continent.

It is, at first sight, somewhat of a far cry from these regions of the White Nile to the coast of Guinea, yet, as we have seen, it is on that line of waterways which form a chain across the continent. At this other extremity we find considerable traces of Amazonian organisation dating back at least several centuries. While Father Alvares describes a woman-dominated state, with women warriors, in the East, M. d'Arnaud and others give us glimpses of female guards on the Upper Nile, and earlier travellers tell us of Amazonian forces in the Congo and Guinea, the latter the very region of which Diodorus Siculus appears to write, the first clear account being of the Monomotapa women soldiers given by Pigafetta, and of the Dahomeyan Amazons penned by explorers between 1703-1730. The latest to deal at any length with the subject of the Dahomeyans is M. Foa, who gave in 1890 many details of the country and the mettle of the women soldiers as proved by their encounters with the French under General Dodd. He says that the force only dates back to the early days of the last century, when Gezo created the female army as a means to guard against a similar accident to that which befell his brother Admozan, who was dethroned by a popular rising. That is, of course, a mistake, as the records of European travellers go back to the early part of the eighteenth century, when the force was apparently old and well-established. Gezo, as a matter of fact, was merely the reorganiser, and in passing we may take note of the curious name of the dethroned brother, which appears to link us up with the Berbers of the north and the Kaffirs of the east, south of the equator. According to M. Foa, Gezo recruited his Amazons from among slave women taken in war. For this purpose young and strong women were chosen, who were confined to the precincts of the royal palace and subjected to a most severe training. The Amazons formed an exact counterpart of the regular army, the officers being women who held equal rank with the men leaders. Many of these female warriors were allowed to marry. They formed part of the standing army, and were at one time 10,000 strong, headed by a Royal Guard of Elephant Hunters, who wore trousers reaching to the knee, short skirts, a linen strip over the upper part of the body, and antlers fixed to their caps. The ordinary women soldiers wore the same uniform but with a small cap adorned with a tortoise badge cut out of blue cloth. They had their heads shaved, and necklaces of beads and amulets hung from their necks. Their arms consisted of short Dahomeyan swords,--a kind of scimitar,--battle-axes, bows and arrows, and flint-lock guns. But the French authority describes the women as anything but good shots with gun or bow, though in hand-to-hand fights they proved exceedingly fierce, and generally victorious over native tribes. These Amazons were allowed all kinds of privileges, having precedence of every one except the chiefs, and when they went forth a small girl preceded them, ringing a bell, so that all men and ordinary women should stand aside and afford a free passage to the truculent warriors, who, we are told, were very masculine and extremely ugly.

M. Foa seems to have been rather hasty in his generalisations, though doubtless accurate enough in describing what he actually saw. But an English traveller had written an account in 1708 of what came under his own observation, and he says that the then King of Dahomey had a great number of women armed like soldiers, "having their proper officers, and furnished like regular troops with drums, colours, and umbrellas." It is also recorded that in 1728 and 1729 the king conquered the combined forces of Wydah and Popos with his Amazonian troops, an account of this expedition being given by Archibald Dalzel, sometime Governor of the Gold Coast, in a book published in 1793, but written many years before. Commander Frederick Forbes, who was in the country for a considerable time, also has much to say about these forces, which he understood were of very ancient origin. He describes them as wonderfully strong and agile, and divided into numerous corps.

Another French observer, the Abbé Laffitte, who was in Dahomey about 1870, had a poor opinion of the morals of these women, but he attests to their bravery and their staunchness to the king. When Gezo attacked Abeokuta and was repulsed with great slaughter, he was personally in great danger, for the men fled, leaving their king at the mercy of the enemy. Had it not been for the Amazons, who stood firm to guard his retreat, Gezo would inevitably have been captured. On this occasion the greater number of the women were left dead on the field. Gezo's successor also attempted to capture Abeokuta, and it was again the Amazons who prevented the retreat being converted into a disastrous defeat, they engaging the enemy while the king sought safety in flight. Abeokuta, by the way, had always been a thorn in the side of their Dahomey majesties, It was a community formed by natives who had been persecuted by the razias of the Amazons, and taking refuge under a rocky hillside, had built themselves a fortified town, which proved impregnable. It is in Yoruba, and its name literally means "under the rocks." In Burton's time, however, the king deemed himself of such importance that he remained in semi-seclusion, and nobody but members of his own family and servants were permitted to see him eat, drink, or take snuff. In Laffitte's time the Amazons were allowed to marry, but only if they were too old or too feeble for warfare. It would seem to have been an economical method of pensioning off used-up warriors. They were, the abbé affirms, hard workers, for the king gave them no rations or pay; so, at all events before marriage, they had to earn their living by labour.

Sir Richard Burton, after his second visit to Dahomey, wrote at once amusingly and instructively on the whole subject. His evidence certainly points conclusively to a long past, though he is by no means inclined to be romantic over either the traditions or persons. He asserts that Gezo had reorganised the force, and for this purpose chose recruits from the most comely and fit daughters of his chiefs. Moreover, they seemed to have, at least nominally, formed part of his harem; so the marriage arrangements, if the French travellers were not mistaken in their facts, must have crept in at a later date, probably to relieve the royal treasury. But there certainly appears to have been considerable variation in the matter of recruiting and organisation.

In Burton's days the Amazon army was composed of the Fanti company of the king's bodyguard, their head-dress consisting of a narrow white cotton fillet with a crocodile cut out of blue cloth sewn on to the band, the hair being cut short, though the head was not shaven. Then there were the right and left wings, including five arms: (1) blunderbuss women, (2) elephant hunters, (3) razor women (who were armed with a razor-like blade, 18 inches long, kept open by means of strong springs, and mounted on a pole 2 feet long), (4) archeresses (carrying the native bow and poisoned arrows), (5) infantry (armed with tower muskets). The elephant hunters appeared to be a corps de parade, while the archeresses had evidently degenerated from a former high estate to a mere body of skirmishers and camp-followers. They had knives lashed to their wrists, wore extremely scanty clothing, and had prominent tattoo marks extending down to the knee. The whole force amounted to about 350 royal bodyguard and 2500 women of the line. The gala uniforms were not without a certain gallant and picturesque effect. A narrow fillet of blue or white bound the hair, the bosom was concealed by a sleeveless waistcoat of various colours, buttoning in front and leaving the arms free. Loin-wrappers of blue, pink, or yellow extended to the ankles, and were fastened round the waist by white sashes falling in long floating ends on one side. Bandoliers, bullet-bags, and short knives completed the outfit. The workaday uniforms were rather more summary, consisting of browny grey tunics, armless, but covering the bosom and extending to the knees; short trousers; and sashes. The bow and arrow women, as we have already said, had a far more primitive costume, probably with the idea of being more adapted for rough camp and bush work. The officers of all arms were distinguished in various ways. Burton says that the female commander-in-chief, who was one of the king's councillors, was a dame of vast proportions. The captain of the royal bodyguard wore a "bonnet like that of a French cordon-bleu, but pink and white below, with two crocodiles of blue cloth on the top, the whole confined by silver horns and lanyards." Another commandress had a silver hammerhead projecting above her eyes, which gave her the semblance of a unicorn. Considering her proportions, this irresistibly reminds us that Pausanias says that the Ethiopian bulls have horns on their noses, evidently referring to the rhinoceros, that unwieldy prototype of the fabled elegant and agile unicorn. All chief women had umbrellas of state, usually emblazoned with their badges of office, also special standards and girl orderlies to carry their guns. The Amazonian bands comprised players on cymbals, drums, and rattles. Much of the manœuvring consisted of elaborate dancing, sometimes in companies or in small groups, with frequent pas de seul.

The Abbé Pierre Bouché, who had seen much missionary service in Guinea and the hinterland, gives quite a different version as regards the recruiting of the Amazons. He says they were chosen from among (1) criminals, (2) the unfaithful in matters matrimonial, (3) nagging wives. Even in Burton's time nagging wives and other social nuisances were "dashed" to the king for service in his army, and there can be little doubt that practice in this direction differed from time to time. But Burton is positive that the harem restrictions were rigorous enough. Bouché, however, like Laffitte, had no high opinion of them morally, though of their courage and capacity for physical endurance he was in no doubt whatever, and he founded his opinion pour et contre both from what he saw and what he had heard from trustworthy witnesses. The abbé quotes a graphic description of a full-dress war-rehearsal at which M. Borghero was present somewhere about 1880. On an open square was erected a broad hedge of prickly cactus; beyond this was a clear space, then a timber house with steeply slanting roof, and beyond that a collection of huts. Three thousand Amazons were mustered, and they had to take the "village" (represented by the cluster of huts) by assault and by a frontal attack. This little game was complicated by the usual conventions which complicate all war games the world over: it was understood that the warriors were to be thrice repulsed (by non-existent defenders) in their assaults on the fort (or aforementioned timber house). M. Borghero was stupefied by the dash and pluck of the women, who swarmed over the prickly barrier with bare feet, scaled the house, twice retired hurriedly, but at the third assault, clambering up the house, slithered down on the opposite side, and then scampered off to surround and enter the huts.

Undoubtedly the Amazons were held in great honour, and accordingly held themselves high in their own esteem; but while they took precedence, they declared, "We are no longer females, we are males," and the most deadly insult to a soldier was to call him a woman.

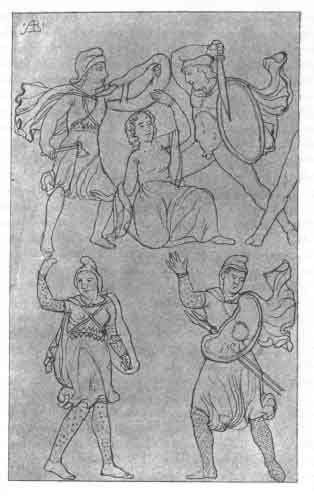

FIGURES FROM CRATES.

DEATH OF PRIAM AT THE TAKING OF TROY.

These contradictions clearly point to considerable changes in an old organisation whose origin was practically forgotten. It certainly can have had nothing to do with any matriarchal form of society, for it tends to show a respect not for women, but for a privileged caste. The official title of the Amazons was Akho-si, that is, "King's Wives," and their popular name Mi-no, or "our mothers." These terms are, of course, conventional. In the Arabian Nights a great Far Eastern king, whose daughter ruled the island of El-Wak-Wak, called his 25,000 mounted lancer women "his daughters," and in Moslem lands it is usual to address an unknown woman, no matter what her age, as "O my mother," merely as a token of honourable intentions. It is possible that the harem arrangement was merely a survival from an old form of royal guard similar to that of the kings of Behr, itself a probable modification of the priestess attendants on a god-king. This would account for the anomaly in the sentiment shown as regards the position of women. On the other hand, Winwood Reade tells us that a princess of the Congo could marry whom she pleased, but the husband had to assume a female name and feminine attire, cover his face, and when he went out he was preceded by a slave beating a drum to clear the way.

It will have been noticed that M. Foa states that the Amazons wore a blue tortoise badge on their headdresses. Whether this was a degenerate form of the blue crocodile seen by Forbes and Burton, or a special fetish of the then reigning king, it is hard to say. The tortoise is one of the amphibians specially honoured by most primitive races, for in their cosmogonies he replaces Atlas, bearing the weight of created world on his carapace. One thing is certain, the crocodile, another amphibian, is most significant locally, for Tokpodun was the crocodile god worshipped in many districts hereabouts, and crocodiles played their part in some of the sacrificial ceremonies, or annual "customs," as he did in Egypt. Lisa, the sun god, had a chameleon as messenger, a kind of Mercury. Snake worship is general throughout Dahomey and well beyond its confines. The python is regarded as the representative of the god who brings good and evil, and is sacred. Danhgbwe, "the snake mother," a small brown and white striped boa, is worshipped at Wydah; the great fetish of the hunters and foresters is Gbwe-ji, a small snake marked like a boa, while Aydo-whe-ho is the heavenly rainbow of the local pantheon, and is represented by a coiled horned snake. Vodun is the snake fetish of the slave coast, and, as we know by Bosman and the dark doings in Hayti, "voodoo" worship involves dancing orgies, in which women take part, and human sacrifice. All this is not without interest, for it brings us back to the snake-clothed, scimitar-bearing Amazons of Diodorus, connecting the warrior women with snake worship, the religious organisation, and, therefore, the kingship.

It is difficult to form an accurate idea as to their numbers, for there have always been considerable divergence in estimates. At times they appear to have been so numerous as to depopulate the country, partly as a result of their organisation, and partly owing to the frequent forays which the existence of a considerable body of warriors rendered necessary. Early travellers, however, were apt to carry away an erroneous impression of the military strength of the kings of Dahomey, because these astute persons were fond of adopting an ingenious ruse de guerre, marching their Amazons across the open exercise ground from the mud gates of the women's compounds to a thicket, the women then doubling back behind the trees to their old quarters, and emerging once more, thus forming units of an endless army. It is an illustration of one of those spontaneously evolved stratagems that may occur to People of very different ways of thinking. We have seen it in our own land, when the red-shawled women of Fishguard passed to and fro on the hillsides in order to deceive the French. This has been dubbed noble with us, though the Dahomeyans have been derided for their methods, which have been likened to the shifts of economically minded theatrical managers; some have even grown indignant at the deception. But indeed we are far too ready to hold the use of a simulacrum in contempt as a mere degrading subterfuge, a symbol, as it were, of hypocrisy. Often, no doubt, 'tis little but the homage paid by vice to virtue. Occasionally, on the contrary, and this more frequently than the unphilosophical allow for, it is the stepping-stone to higher things. Discontented with affairs as they exist, the husk is retained, the essential being neglected while groping about for the better. And these, dry husks though they are, may be infinitely preferable to the real thing, "the essential."

Thus, when men grew doubtful as to the ethics of slaughtering slaves to the end that they might be buried with their dead lord, so that a worldly servitude should be continued by ghostly drudgery in the Land of Shades; or of the justice of decapitating a prisoner of war in order that he should become a sleepless sentry, his grinning head being stuck on a long pole to keep never-ceasing guard over the captain's hut or grave; and in their doubt substituted clay dolls, painted effigies, or dropped into the yawning grave whole troops of men, women, and little children scored on bark, stone slabs, or other convenient materials, and placed a graven image as a guard over the tomb instead of a genuine skull or stuffed skin--the simulacra proved an advance on the real things. No doubt they were mere empty forms, and suspiciously profitable to the surviving relatives, but they certainly were a gain to potential victims and to humanity. So when His Majesty of Dahomey had to eke out his thinned Amazonian bands by a trick, the subterfuge showed that growing humane feeling or exhaustion (which may powerfully help towards virtuous deeds) had depleted his hungry army, to the relief of his own country and his neighbours', and here too the make-believe was an improvement on the reality. Humanity is a frail thing, and is rarely strong enough to be off with the old love before it is on with the new.

As we have said, Dahomey is not the only country on the west coast where Amazons have been employed within modern times. The King of Yoruba had a woman bodyguard, so numerous, indeed, that the dusky monarch boasted that if they clasped hands they would reach across the kingdom; while in Bosman's day the petty King of Wydah had from 4000 to 5000 "wives," who executed the royal sentences. Moreover, we have a link connecting the West with Central and Eastern Africa. This is afforded by a spirited account by Pigafetta of the many adventures of Eduardo Lopez, who was in the kingdom of the Congo about 1580. In describing the empire of Monomotapa, he says that among the soldiers were legions of fighting women. They were highly esteemed, used the bow and arrow with considerable dexterity, and, in order to facilitate their doing so, burnt away the right breast. We are told that "they are very quick and swift, lively and courageous, and very cunning in shooting, but especially and above all venturous and constant in fight." They used cunning, often appearing to run before the enemy, and then turning to resist their advance. When hard pressed they dispersed in all directions, then, circling about, encompassed the foe on all sides. According to these Portuguese observers, the women enjoyed the king's favour, and had certain countries, or districts, assigned to them, where they brought up the female children, but sent away the boys at an early age. Lopez reported that in the north-east of the Congo Empire, "at the beginning of the Nilus," there dwelt the monstrous tribe of Giachas, or Agagi, giants who "feed upon man's flesh," who scarred their lips and cheeks with certain lines made with red-hot irons,1 and who were at continual war with the Congolese Amazons, evidently engaged in the attempt to penetrate to a more fertile country, being pressed by the barbarian invasion of their own country, as explained in the early part of this chapter.

We have a kind of echo of this from Father Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, in his absorbing history of Ethiopia, wherein, referring to the Congo, he says that in 1640 Llinga, a daughter of the late king, succeeded him, but, refusing to submit to Portuguese supervision, was driven from her country. However, she seems to have been well endowed mentally and to have exhibited considerable qualities as a ruler, as well as those of a warrior, for she kept a large following, carried on armed resistance for a long time, returned to the Congo, and forced peace on the wearied Portuguese. She clad herself in skins, carried axe, bows and arrows, and a sword. Even after her return she made strife a profession, probably in order to maintain her supremacy among a turbulent people; and one of her amiable customs was to offer a man as a sacrifice before going to war, striking off his head with her sword and publicly drinking his blood. She apparently had female assistants in her tyranny. Father Cavazzi goes on to tell us of another Amazonian virago in this region who cherished designs of forming a state of warrior women. Early in the sixteenth century the Congo was invaded from the north-east by the stalwart fighting Jagas. So it will be seen that the cannibal giants of Lopez' days still harried the kingdom. The Jagas committed great ravages under their chief, Zimbo. He, however, was ultimately defeated and driven south. journeying towards the Cape, he suddenly turned north, and creeping up the coast, settled on the banks of the Cunene River, where he formed a kingdom. On his death Zimbo was succeeded by one of his captains, who in turn was succeeded by his wife, Mussasa. Their daughter, Tembandumba, had been named after the celebrated consort of Zimbo, and was brought up to warlike pursuits.

It is a matter for curious conjecture whether this warlike training of the Jagas women was due to their experiences on the Upper Nile or to their contact with the old Amazonian troops of Monomotapa. In any case, while still quite young, Tembandumba seems to have nourished ambitious projects, and, the better to attain them, associated with herself a number of young girls, training them by fighting and hunting. She declined to be ruled by convention, and only entered into temporary matrimonial alliances, though scrupulously killing her lovers after very brief dalliance. Thus she, at all events, was always unmistakably off with the old love before she was on with the new. Her next act of self-assertion was to rebel against Mussasa and proclaim herself queen. She then organised the nation on a war footing. She commanded that all male infants, all twins, all females whose upper teeth appeared before their lower ones, and all those born within villages, should be killed by their mothers, the bodies pounded in mortars and, mixed with herbs, converted into magic ointment. Temporary husbands were to be captured by force of arms. The better to enforce male infant sacrifice, the queen assembled the tribe, and tearing her baby boy from her breast, flung him into a mortar and pounded him to death, adding herbs and roots, and forming an ointment which she rubbed all over her body, declaring herself thus rendered invulnerable. Other mothers, seized with imitative frenzy, did as the queen did, and then followed her to war. Before long, however, there arose a certain amount of passive resistance; male infants were kept in secret, and Tembandumba had to appoint officers to slay new-born babes.

Finally, she had to abandon her idea of the woman state, and she accepted male infants captured in war for ointment-manufacturing purposes. The tribe was cannibalistic and offered human sacrifices; women, however, were only killed on the death of great chiefs, first as a matter of enforced routine, and later as voluntary candidates for post-mortem honours. Tembandumba kept her people in continual strife, ruling mainly through women. Then she fell under the spell of one of her husbands, and, tolerating him too long, was poisoned when she began to manifest tokens of conjugal unrest. She was a repulsive-looking creature, and her magic ointment had not been used as an eye salve, for she lost one of them in battle. Thus ended this curious experiment, which may be paralleled with the traditions of Valasca's rule in Bohemia. But Cavazzi's story is mainly that of abnormality. Unless we conjecture that the Jagas brought their women-warrior and women-ruling proclivities from the Nile basin, it is less significant than that of Edward Lopez, whose tale of a royal female guard employed on desperate undertakings links up the Congo with Guinea and the White Nile, and so, in a sense, completes this African circle, stretching from Abyssinia to Dahomey, with a great loop south of the equator, taking in this Cunene colony as its extreme limit.

Footnotes

112:1 These were the pillars which the Spanish monarchs were to assume as part of their heraldic insignia, and which their lieutenants still later were to imitate when taking possession of huge tracts of country in the New World in the name of their sovereigns.

133:1 Tattoo marks are used primarily as tribal and professional badges, originally being connected with totemism, the adornment for the sake of personal attraction or repulsion (in love matters or warfare) being a natural development of the system. Ancient legends say that the Annamites, being in sore danger from monsters of the air and sea, tattooed themselves so as to resemble dragons and fishes, becoming brothers thereof. Hence, probably, the wonderful dragons and fishes spread all over China and Japan. Man held himself as a descendant of fierce animals, and adorned his body with cicatrices, dyes, or skins p. 134 accordingly. Hence the use of the pelts of lions, leopards, and buffaloes, the cloaks of birds' feathers, the snake coverings of the Libyan Amazons, and the peculiar clothing of the present-day "Fish-Skinned" Tatars of the Amur. It is curious to find that in Bruce's time certain tribes of the Sudan tattooed their stomachs, sides, and back with fish-scales. The god-king and priest-king, who sat on the thrones provided with animals' feet and birds' claws, and had footstools of their ancestral beasts, when they died were often depicted so as to show this peculiar union, and they appear with the body of a lion or the head of an eagle. The priestly class and devotees tattooed themselves with the symbols of their deities. That the practice was regarded as idolatrous is shown in Leviticus, where we read (xix. 28): "Ye shall not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead nor print any marks upon you." Pliny, who speaks of the Moseyni, who dwelt near Themyscira, as a tribe "who make marks upon their bodies," said that the Daci also made scars on their arms to denote their origin, and that these marks were reproduced on new-born babes unto the fourth generation, though Aristotle holds that these birth-marks disappeared after the third. As regards the sacerdotal use of cicatricial tattooings, M. Foa says that the priests and priestesses of Dahomey, especially those of the Serpent and Thunder, were horribly tattooed. One peculiar form was like a web. A number of filaments of skin were arranged in concentric circles and united by cross filaments to a central knob of skin, the whole design being detached from the body except at its outer circle. This is undoubtedly of a symbolical nature, referring to mysteries and magic. Much of the tattooing is conventionalised to the extreme limit, differing from the practice of the Pacific islanders or the paintings of American Indians. For instance, the turkey totem of the Lenapé is represented by the imprint of the claw; on the west coast of Africa the horns of the antelope by two curved lines (also seen in India); while the tortoise is shown as a square, with projecting outline for the four paws, and a straight bar across for the head and tail. Much of the tattooing in Africa on the lips and cheeks, as was the case with the Nile Jagas, or on the forehead and breast, on the trunk as with the Sudan fish tribe, or on the legs as with the Dahomeyan elephant huntresses, consists of mere dots and lines, occasionally with curves (or snakey lines). Now, it is to be noted that the divination board, somewhat like an exaggerated backgammon board, with its men of sacred palm kernels, is widely used. The combination of numbers seems to be closely connected with notions of religious organisations--the different spheres of action, number of gods, hierarchy of priests, and so on. This idea of numbers we find among the Assyrians, where Anu, the Creator, was represented by the number 60; Sin, the sun god, by 30; Ishtar, the moon goddess, by 15. It has to do with the mystery of numbers, whence the sacredness of the numbers three and seven, and the mathematical jugglings of the magicians, white or black, and was, no doubt, derived from astrology and the practical application thereof.

Next: Chapter VIII: Amazons of America