The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER VIII

AMAZONS OF AMERICA

WHEN Christopher Columbus was returning from his first voyage of discovery, he was told by the Indians of Hispaniola of another island, called Mantinino, which was inhabited solely by women. They employed themselves in labour not suited to their sex, using the bow and arrow, hunting, and going to war. Once a year they received Caribs from other islands among them, the men only staying a short time, and on their next annual visit taking away with them the male infants that had been born, the girls remaining with their mothers. These women, besides using bows and arrows, had defensive armour of brass plates. This intelligence added to the admiral's conviction that he was on the coast of the Indies, for the ancients had spoken of islands where the Themysciran Amazons had taken refuge, and one of his own countrymen, a great traveller by land, the Venetian, Marco Polo, as we know, had given an account of what was considered by many as their last abode. But although Columbus constantly heard rumours of the mysterious island, which often seemed to be in the immediate neighbourhood, yet ever receded, he was not destined to see it or any of its inhabitants. No one, indeed, succeeded in identifying the particular island of which the natives of the Caribbean Sea seemed to give such explicit details. Other Spanish adventurers, however, had different tales to tell.

In 1540, some forty years after Allonzo Pinzon had discovered the great Marañon, Francesco de Orellana, making his way from far-off Peru to the Atlantic through the Brazils, explored the magnificent river, he and his companions meeting with many difficulties. They were told of a race of pigmies, of men whose heads grew out of their backs, of others whose feet were turned the wrong way round, so that if any one attempted to follow in their tracks, the pursuers were misled, actually receding from those they desired to catch up. There were also men with tails, and stories of the Ozacoulets, a tribe of warriors with white skins, blue eyes, and long light-coloured beards; but most persistent of all were the rumours of warrior women who lived apart from men. The grandeur and novelty of the scenes they were passing through, the weirdness of the stories they heard, all prepared the Spanish adventurers to accept the marvellous, so that when they had accomplished rather more than half of their journey, and were approaching the Trombetus River in the neighbourhood of the great, densely wooded island of Tumpinambaranas, formed by the junction of the Madera with the Marañon, they found themselves opposed by warlike natives gathered on the banks, and among them noticed women seemingly acting as leaders of the men, they readily fell into the notion that here they had stumbled upon the renowned Amazons. In this belief they were confirmed by the natives whom they cross-examined, and de Orellana, duly impressed with this wonderful discovery, and some say actuated by a desire to magnify his own exploits, renamed the Marañon River the Amazon, a name subsequently given to a whole vast province.

Garcilaso Inca de la Vega, in his account of the expedition of Gonzalo Pizarro and his lieutenants, quotes Father Carbajal, who was in the train of de Orellana. The good father says that the Indians attacked the small but well-armed party of Spaniards so fiercely because they were tributaries to the Amazons, which betrays a certain confusion of ideas with Asiatic traditions. However, he and others of his Spanish companions saw some ten or twelve Amazons who were fighting in the front ranks of the Indians, acting as though they were in command, and with such vigour that the Indians did not dare to turn their backs, and those who fled before the enemy were killed with sticks by their own party. These women appeared to be very tall, robust, fair of complexion, with long hair twisted over their heads, skins of wild beasts wound round their loins, and carried bows and arrows in their hands, with which they killed many of the explorer's party.

These rumours of the Amazonian nation were plentiful, but no one ever came across the country, at least no one of sufficient standing to give accurate geographical indications. The country was supposed to be buried in the gloomy forests, though it was said to possess rich cities. Some time after the adventure of de Orellana and Carbajal, another missionary, Father Cristobal de Acuña, who had long dwelt in the Brazils, gave, in his New Discovery of the Great River of the Amazons, considerably more details. "These man-like women," he writes, "have their abodes in the extensive forests and lofty hills, among which that which rises above the rest, and is therefore beaten by the winds for its pride with most violence, so that it is bare and clear of vegetation, is called Yacamiaba. The Amazons are women of great valour, and they have always preserved themselves without the ordinary intercourse with men; and even when these, by agreement, come every year to their land, they receive them with arms in their hands, such as bows and arrows, which they brandish about for a time, until they are satisfied that the Indians come with peaceful intentions. They then drop their arms and go down to the canoes of their guests, where each one chooses a hammock, the nearest at hand, which they take to their own houses, and, hanging them in a place where their owners could recognise them, they receive the Indians as guests for a few days. After this the Indians return to their own country, repeating their visits every year at the same season. The daughters who are born from this intercourse are preserved and brought up by the Amazons themselves, as they are destined to inherit their valour and the customs of the nation; but it is not so certain what they do with the sons. An Indian who had gone with his father to this country when very young stated that the boys were given to their fathers when they returned the following year. But others--and they appear most probable, as it is most general--say that when the Amazons find that a baby is a male, they kill it. Time will discover the truth; and if these are the Amazons made famous by historians, there are treasures shut up in their territory which would enrich the whole world." This is much the same story that was gathered by Columbus, though the admiral's will-o'-the-wisp tribe are supposed to be on an island of the Caribbean Sea, while those brought before de Orellana were on the mainland, some said hidden in the forests, others safe on an island formed by the sweep of two rivers, an island like Tumpinambaranas, which is 210 miles long and contains 950 square miles, or, again, on an island in one of the great lakes.

Alas for the good father! time exploded the legend, at least as he understood the matter. Neither Amazon nation nor their fabulous treasures have ever been found. Yet it was not from any want of willingness or energy on the part of the Spaniards. Animated by stories such as those recorded by Acosta and Herrera and sworn to by wandering whites and natives before the Royal Audienza at Quito, there was real enthusiasm and emulation displayed in furthering exploration for this constantly receding country "where women alone are." Nuño de Gusman, writing in July 1530 from Omittan to the Emperor Charles V. (Charles I. of Spain), says, with cheerful anticipation of what was in store for a lucky and enterprising Don, "I shall go to find the Amazons, which some say dwell in the sea, some in an arm of the sea, and that they are rich and accounted of the people for goodness, and whiter than other women. They use bows and arrows and targets; have many great treasures." We find, among others, Hernando de Ribera conducting a search party. He came across many natives who reported to him that beyond the Mansion of the Sun--that is to say, westward of a great lake wherein the sun sank daily to rest--there would be found that much-sought-after country "where women alone dwelt." This might allude even to Peru, where, among the Cordilleras of the Andes, temples of the sun had been built on high mountains, such as Intihuatana, "the Seat of the Sun," a fortress temple on a high hill near Cuzco, in the vicinity of Lake Titikaka, some 1300 feet above sea-level. There was, however, no record of women warriors on that side of the Andes, at all events in the days of the Incas. To return to Brazil, Ribera was told that the women possessed both white and yellow metal (silver and gold) in such abundance that they made their seats and household utensils out of them. Close neighbours of theirs, so it was said, were the pigmies, who formed a nation by themselves. About forty-seven years later Anthony Knivet, who went with Thomas Candish on his second voyage to the South Seas, was captured by the Portuguese, escaped, and wandered through Brazil. He heard of the Amazons, and, indeed, claimed that his Indian companions said that they traversed the mysterious country; but when Knivet urged an attack on the women, the natives "durst not, for they said, We know that the country is very populous, and we shall all be killed."

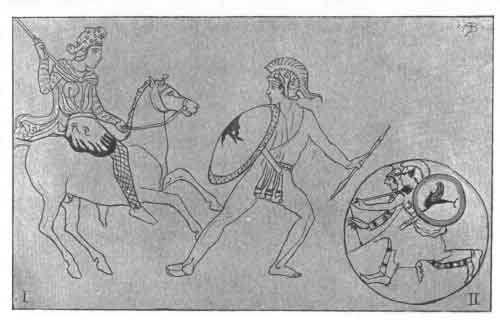

I.--FIGURES FROM CRATES FROM SIR WM. TEMPLE'S COLL. BRITISH MUSEUM. COMBAT OF GREEKS AND AMAZONS.

II.--KYLIX. TWO AMAZONS CHARGING. BRITISH MUSEUM.

On the other hand, we hear rumours of the Amazons in quite another direction. Sir Walter Raleigh, in his Discovery of Guiana, says that he spoke to a cacique who had been to the Amazon River and beyond. This chief reported that "the nations of these women are on the south side of the river, in the province of Topago, and their chiefest strength and retreats are in the lands situate on the south side of the entrance, some sixty leagues within the mouth of the same river. The memories of the like women," adds the gallant knight, "very ancient as well in Africa as in Asia, in many histories they are verified to have been in divers ages and provinces, but they which are not far from Guiana do accompany with men but once a year, and for the time of one month, which I gather by their relations to be April. At that time all the kings of the borders assemble and the queens of the Amazons; and after the queens have chosen, the rest cast lots for their valentines. This one month they feast, dance, and drink of their wines in abundance; and the moon being done, they all depart to their own provinces. If they conceive and be delivered of a son, they return him to the father; if of a daughter, they nourish it and retain it. And as many as have daughters send unto the begetter presents, all being desirous to increase their own sex and kind; but that they cut off the right breast I do not find to be true. It was further told me that if in the wars they took any prisoners that they would accompany with those also at what time soever, but in the end for certain they put them to death; for they are said to be very cruel and bloodthirsty, especially to such as offer to invade their country. These Amazons have likewise great store of these plates of gold, which they recover in exchange chiefly for a kind of green stones, which the Spaniards call piedras hijadas, and we use for spleen stones: and for the disease of the stone we also esteem them.

Of these I saw divers in Guiana, and commonly every cacique has one, which their wives for the most part wear, and they esteem them as great jewels."

Then the direction again changes, and we hear of the women on the north side of the great river, retreating up the Rio Negro, ultimately hiding successfully in Guiana. Raleigh says: "On the south side of the main mouth of the Orinoco are the Arwacas, and beyond them the cannibals [Caribs], and to the south of them the Amazons." Many years after this Father Gili, writing of the Orinoco and its neighbourhood, said he closely questioned an Indian as to the surrounding tribes. Several were mentioned, and among them were the Aikeambenanoes: "Well acquainted with the Tanamac tongue," the priest declares, "I instantly comprehended the sense of the last word, which is a compound and signifies 'women living alone.'" The Indian at once confirmed his interrogator's conjecture, and giving certain details of these near yet unapproachable women, alleged that their chief industry was the making of blowpipes for the discharge of poisoned arrows in war and in the chase. When de la Condamine went through Brazil in 1745 he also questioned the natives closely as to the Amazons, and he heard of an old Indian whose father had actually conversed with "the women without husbands." On reaching the village, it was found that the old man was dead, but his son, aged apparently seventy, said that his grandfather had spoken to four Amazons, one of whom was suckling an infant at her breast, as they passed from the south side of the river to go up the valley of the Rio Negro.

Another Indian living near Para actually offered to show a river farther up which (beyond the falls in the mountain fastness) the Amazons were to be found to that day. Unfortunately, this offer does not seem to have been accepted. The upper regions of Guiana appeared to be the centre most spoken of in these days as the home of the women. Although he says, "I know that all or the greater part of the Indians of South America are liars, credulous, and enamoured of the marvellous," still de la Condamine saw no reason for scepticism, even as regards the more elaborate details of the tribe and the manner of its maintenance.

Of the origin of the "women who live without husbands" a very significant legend appears to have been current along the middle and lower reaches of the Amazon. We are told that in some far-off indeterminate age the women rebelled against their husbands and retired to the hills accompanied by only one old man. They lived by their own industry, quite isolated. All daughters born to this lopsided community were carefully reared, while all boys were killed. Then one luckless male baby, coming into the world deformed and covered with scars, called forth maternal pity. In secrecy the mother lavished all her tenderness and art in the endeavour to cure her child, but without effect until she placed him in a strongly woven bag and squeezed him into a lovely shape. Thereafter he grew apace in seclusion, day by day becoming more charming in form and character. Eventually his retreat was discovered. Then began a long and tender persecution from the women, though the boy remained unmoved. Mother and son consulted together, and to escape his tormentors the youth was thrown into the lake, where he assumed the shape of a fish. Whenever the mother called, the fish swam ashore and was instantly transformed into his beautiful human form, taking food from the hands of his mother. Jealously guarded though the secret was, feminine curiosity soon ferreted it out; and then the other women, imitating the calls, clasped the deceived young man in their arms. It was next the turn of the old man to grow uneasy, for he noticed that he was being neglected. So he set himself to watch, and the spy was driven to fierce anger by the scene of magic enacted before his eyes. His own calls to the fish were of no avail, so he made strong nets. None was stout enough, however, for always the boy-fish escaped, breaking through the meshes. The old man sat down and thought deeply, and decided upon a plan. Going to each woman of the tribe, he craftily begged them for tresses of their hair. Therewith he made a net so strong and entangling that he promptly caught and killed the fish. After this the women finally abandoned the slayer; but while he was away in his fields, his hut was always put in order by some unknown agency, and his meals prepared for him by unseen hands. So again he hid and set himself to spy. And then he saw a pet parrot fly down, put off her feathers, and swiftly change into a beautiful girl, who at once set about her duties with painstaking industry. To rush forward and fling the feathers into the fire was the work of an instant, then the watcher turned and demanded, "Who are you?" "I am," replied the mysterious squaw, "the only woman who ever loved you. Now you have broken the spell I was under, and I am glad."1

A variant of this is given by Barboza Rodriguez. He records a legend which shows the women as rebels against their husbands, flying to the woods, and protected in their flight by the elements and wild beasts. The men found their passage barred by flood and tempest; fierce animals fought them; monkeys gathered in the trees and pelted them with deadly missiles. So the women retired and led their own lives. Then they repented, and admitted the men to their presence once a year, giving up the boys to them, but retaining the girls. And so matters went on, until one day the whole tribe of women disappeared down a hole in the earth, led to their last resting-place by an armadillo.

It would take us too long and certainly carry us too far from our present inquiry to fully analyse each clause of these exceedingly picturesque and pregnant stories. Some points, however, may be briefly noted. In these accounts of the Amazons we have a motive for their existence introduced which is quite distinct from anything suggested by the Greeks in the case of those of Asia. In the first story, the women retiring to the hills accompanied by one old man have all the appearance of a religious guard surrounding a priest-king. There is more than one hint of sacrifice, pre-eminently so in the case of the boy-fish, here introduced as a symbol of fertility; and finally in the most instructive version of the fable of net-entanglements--magic and woman's wiles. Hair is woman's delight and glory, but also a great means of offence. In certain cities of Asia Minor, Ashtoreth demanded the shaven head as the lesser of two personal sacrifices from her female worshippers. The Talmudists say that Lilith, the semi-human, semi-demon first wife of Adam, would, when she could, strangle the sons of men with tresses of her golden hair, out of revenge for the disinheritance of her own offspring, the Jinns. For this reason the amulet "childbirth tablets" hung on the walls of lying-in rooms of Jews both in the East and Eastern Europe always bore a representation of Lilith with an invocation for protection. But to return to our Brazilian legends. In the second, far less complicated, there is yet much that is suggestive, for here too we see the women set apart, protected supernaturally, and ending by sacrifice. For the descent into the earth means death, and its collective form and the leadership of the armadillo hints if not at the inhumation of the living, at least sacrificial burial on the death of some semi-divine chief.

It will be observed that in these two fables we are not asked to look upon the women as of a bellicose disposition-apart from their initiatory quarrel with their husbands--or as belonging to a war organisation. As a rule, however, the stories all laid stress upon their fighting, qualities, and this was very persistent among the Caribs, themselves a most warlike people.

Sir Robert Schomburgk, who knew Guiana and Venezuela so well, declaring that the "Caribs are most versed in wonderful tales," disbelieved all these rumours. Of course it was impossible altogether to ignore the positive assertions of eye-witnessing Spaniards, and so, to explain these away, Sir Robert suggested that they had mistaken young men with flowing hair, and wearing necklaces and ear-rings, for women; an opinion backed up by several other authors. This is not convincing, for we must remember that Father Carbajal expressly states that the fighting women he and his companions saw had their hair twisted round their heads. A recent writer, Mr. C. R. Enoch, in his book The Andes and the Amazon, quotes an official Peruvian report on the native tribes inhabiting the forest regions and eastern slope of the Andes, in which the following passage occurs: "The Nahumedes are an almost extinct tribe, on the river of the same name. They are those who attacked the explorer de Orellana, who believed that these savages, with their chemises and skirts and long hair, were women warriors, or Amazons, and which name was given to the river. This must be the explanation of the supposed existence of women warriors in these regions, for no legend or history among the Indians can be found relating to any empire of women." This is an example of doubt carried to extreme limits. If the Nahumedes are the people who attacked de Orellana, they have shifted their ground considerably, which, of course, is quite possible; but it is too much to say that the Indians possess no traditions of a tribe of fighting women, in face of the legends and rumours gathered not only by such men as Father de Acuña and those more or less his contemporaries, but by such travellers as de la Condamine and others.

We do not find among early writers any claim that the female warriors were called by any local name remotely approaching that of Amazons, although these writers had always clearly in their minds the Asiatic and African stories. A recent authority, Dr. D. G. Brinton, however, has made the curious discovery that the word amazunu is used by the natives at the mouth of the mighty river to describe "a torrent of roaring water," and as especially applied to a bore at the outfall of the Marañon. Thereupon he suggests that the Spaniards heard this term used in reference to something wild, impetuous, and dangerous in connection with the river, and straightway evolved a non-existent tribe. It is only fair to say that there is no evidence of this in Carbajal's account or that of de Acuña. Still, it would be interesting to trace the origin of such a compound word. It is certain that the river and province was named by the Spaniards from "the Amazons made famous by historians," descendants of whom they imagined they had stumbled upon, and not from any chance name uttered by the Indians. Is it possible that the compound word is, after all, of later date than the Spanish Conquest and the renaming of the river? Such tricks of philology are by no means uncommon.

As late as 1743, when de la Condamine was travelling through the country, rumours about the Amazons still persisted, but, like de Acuña, de Ribera, Gili, and many more, this worthy explorer never caught a glimpse of them or the mysterious Manoa. He could only meet people who said they had seen them in some remote, ill-defined region, and who knew others who had years before visited the women and country, which, however, could never be located. When de la Condamine was making his inquiries, it was said that the Amazons had moved off up the Rio Negro, and they continued to retreat before the inquisitive whites into the unmapped forest regions of Guiana. Humboldt, like de la Condamine, was a strong believer in the tales, though his investigations were as little conclusive. Sceptics were equally numerous, and some had made their voices heard even in the days of the conquistadors. There were those ready to insist that the legend grew from the crafty designs of de Orellana, who wished by these devious means to wipe out the memory of his gross treachery to his chief Pizarro, thinking that by marvellous accounts of his own exploits he would wrest applause and rewards from those at home. It is scarcely necessary to attribute wilful intention to mislead on the part of Father Carbajal and other explorers on this head. That women did appear in arms in America as well as in Asia, and for the matter of that in Europe too, there is no reason to doubt. Many instances may be cited.

Juan de lo Cosa reported that when he sailed with Rodrigo de Bastides in 1501 he landed with a party far north of the Orinoco on the site now occupied by Cartagena, and he and his party were boldly attacked by men and women who mingled in the fight, both sexes wielding most dexterously the long dart, or azagay, and bow with poisoned arrows. Hulderick Schnirdel, who travelled in company with Spaniards through the country of the River Plate and the Amazon between the years 1534 and 1554, heard much of the fighting Amazons, who were said to live in an island, to have no silver or gold, which they left with their husbands on the mainland--altogether a novel account. Schnirdel went in search of the island, but fruitlessly. He doubted that a nation existed, though he attests that the fighting of women in the ranks with their menkind was common enough. A little later, in 1587, Lopez Vaz recounts the adventures of Lopez de Agira. This de Agira was the rebel and renegade who murdered Don Fernando de Gusman, who had proclaimed himself Emperor of Peru. After the murder, de Agira, accompanied by a few soldiers and natives, started down the Amazon en route for the Atlantic. They met with some opposition, and found it was true that Amazons existed--"that is to say, women who fight in the wars with bows and arrows; but these women fight to aid their husbands, and not by themselves alone without companies of men, as de Orellana reports. There were of these women upon divers parts of the river, who, seeing Spaniards fighting with their husbands, came in to succour them, and showed themselves more valiant than their husbands." But the comparative rarity of the phenomena would be sufficient to stir the imagination of the Spaniards, whose minds, as we have said, were stored with stories of the classic period and tales of the East.

The early Spanish critics accepted the story of the fighting women, as evidence to this effect accumulated, while more or less politely disbelieving the story of Amazon "nations," and their arguments are based on the very fact that women fight side by side with their husbands, and that such-like warrior women were well known both in ancient and modern history. It must also be remembered that America was still part of the Indies to most of the early explorers, and to them it seemed quite natural that the famous Themysciran nation should have migrated farther afield. It followed that these explorers should find that these warrior women were white, for so the fitness of things demanded, though there is a possible explanation for a light-coloured band of women if we suppose them to have belonged to a semi-religious caste. Then there was another school, holding that this nation of women was the remnant of those who had escaped from Asia through Africa by way of Hesperides or the lost Atlantis. To most of the travellers, as with Father de Acuña, the "Amazons made famous by historians," or, in other words, the Asiatic dames, could not be forgotten, and the stories of fabulous wealth could only contribute to their belief.

Down to quite recent times there were persistent rumours of wonderful cities hidden away in almost impenetrable forests, stored with great treasures of gold, and often said to be guarded by women, though we see from Schnirdel's report that the office of treasure-guardianship might be reversed. The typical examples were the phantom cities of Dobayba, where there existed a golden temple to a Nature goddess, and Manoa del Dorado, so constantly talked about as near at hand, but never seen: the latter a city with houses roofed with gold, bathed by a crystal-clear lake, the waters rippling over sands of gold. Now, in justification of this, we may point out that when the Spaniards came to Peru for the second time, and made the unfortunate Emperor Atahualpa prisoner in his own castle of Cajamarca, the Inca offered as a ransom to fill a room, said to be 22 feet by 27 feet, as high as he could reach, say 6 feet, with gold. This, it has been estimated, would have amounted to a value of a hundred million sterling. But the Spaniards were impatient, and slaughtered their prisoner, a proceeding indefensible on moral grounds, and as a matter of policy less sensible than killing the goose that laid the golden eggs. The treasure was never forthcoming. Yet at Cuzco, the true capital of the Inca power, and at Pachacamac, the Spaniards found the palace walls covered with plates of gold. Offerings of gold chains and flowers of golden plates also seem to have been thrown into lakes. At the birth of the last undoubted heir of the Incas, who received the symbolic name of Huasca, "The Chain," or "The Cable," a commemorative chain said to be 233 yards long and composed of heavy links of gold was made and cast into Lake Orcos, no doubt as a thanksoffering.

That the sands of lakes and rivers abounded in alluvial deposits of finely powdered gold is true to this day as it was of old. Stories of such richly endowed cities were not confined to Brazil and Peru, but were common to Guiana, Honduras, and so on. The grounds for these legends were perfectly natural, as we have just shown. Besides, many of the most wonderful buildings of the Incas, Aztecs, and others were placed either in most difficultly accessible mountains, or on islands in big lakes, or in dense forests. Von Hassell in 1905 explored much of the upper reaches of the Amazon on the Atlantic side of the Cordilleras, and he visited the great fluvial island of Tumpinambaranas, where he found stupendous ruins, reminding him of the civilisation of the Incas. He says that the Amazon plain must have been visited by repeated waves of emigrants, having civilisation as advanced as that of the Incas, but who had disappeared, leaving faint traces behind them. Baron Nordenskold, on his travels in Chaco, in Argentina, "found large places in the primeval forests beyond the real Calchaqui territory, in districts at present very sparsely inhabited."

The Toltec city of Quiché, capital of Utatlan, Central America, apparently had a population of 3,000,000, and the Spaniards' description of the Royal Palace reads like an account of the Alhambra in its days of glory. Experience taught that it was customary for people threatened with invasion to remove their treasures to as inaccessible retreats as possible, where, also, the womenfolk would be gathered, and these, in default of men, would as occasion demanded take part in the defence of their lares and penates. Villages, too, were often occupied by women, old men, and young children alone for many weeks together, while the men and youths were away on the war-path or some great hunting expedition. Moreover, in this part of the American continent, where moon-worship prevailed, there were certain ceremonies connected with womanhood and child-bearing involving the separation of women from all males, and apparently elaborate dances in the moonlight. Upon these solid enough foundations the Spaniards, by frequently injudicious questioning of the natives, built up a rickety superstructure of many strange fables. The evil practice of our own Counsels learned in the law have taught us the very real danger of putting leading questions, even when addressed to educated people able to grasp their meaning. But when you have a credulous cross-examiner, bewildered by the novelty of his surroundings, his head stuffed full with the stories from Quintus Curtius and Diodorus the Sicilian, and on the other hand a horde of naked savages, or even of semi-barbarians, catching most imperfectly at the meaning of their questioners, it will be readily seen that the answers easily took the form that the interlocutor more or less unconsciously desired.

That women did fight on occasion--and this would be particularly true of the hill and forest tribes--we have already seen by various travellers' accounts. That they were occasionally for a length of several moons a tribe, as it were, by themselves, and guardians of tribal treasures, there is no reason to disbelieve. Ample material here for a very robust and circumstantial legend, without either party to the making thereof being, liars of malice aforethought.

An extraordinary fact, which should be mentioned in this place, as it may have some bearing on the subject, is that the Lenâpé tribe of North American Indians were called "Women." They were a branch of the great Algonkin nation, but found themselves down in Delaware, surrounded by the warlike Iroquois. That they could boast of an honourable origin is proved by the fact that the three Delaware sub-tribes had as their totems the tortoise (above all honoured as the servant of the All-Powerful Creator, and on whose back the earth was built up), the wolf, and the turkey. Moreover, Dr. Brinton informs us that Lenâpé means "men of our nation," or "our men." Yet it appears that for a lengthy period this tribe never went to war, and although in later years apparently not held in high esteem, unquestionably filled an important office as a kind of buffer nation of peacemakers. Among most American tribes there existed a Council of Women, composed of the old matrons, whose privilege it was to meet in war-time and discuss matters affecting the tribe. If they advocated peace, it was no disgrace for the "braves" to listen to them and consider the advisability of offering terms to the enemy. It was in some such position as this that the whole tribe of Delaware Algonkins were placed. According to their own statements, the Lenâpés became the peacemaking tribe at the special request of the Iroquois, who saw that the nations were eating each other up. So they approached the Lenâpés with an honourable proposition, and in the presence of the other assembled tribes gave the Delawares the long robe and ear-rings of women, so that they should not bear arms or mingle in strife; the calabash of oil and medicine, to the end that they might become the nurses; the corn pestle and hoe, so that they might cultivate the land; and, in order to emphasise the whole solemnity, bestowed on the chiefs of the "Women" tribe a belt of wampum, the greatest of symbols of peace and fraternity within their gift, as each division of the strange ceremony was reached. That the Lenâpés fulfilled their mission seems certain, although as time went on the Iroquois began to treat them as a conquered tribe, and used the term "Women" as applied to them with some contumely. This buffer tribe, with its claims to a high mission and its equivocal position and attributes, appears to be unique in American Indian social economy; on the other hand, at all events in the southern part of the continent, there were classes of men in the barbarian nations dressed and treated as women. The whole problem of the "Women" tribe, however, is far from being cleared up. Was it cajoled into its curious place as the result of some dim recollection of a once-powerful women-priest caste? Or was it merely a clever device suggested by pressing needs when it began to be recognised that there must be occasional cessation from the interminable intertribal slaughter? It is a mystery full of suggestion.

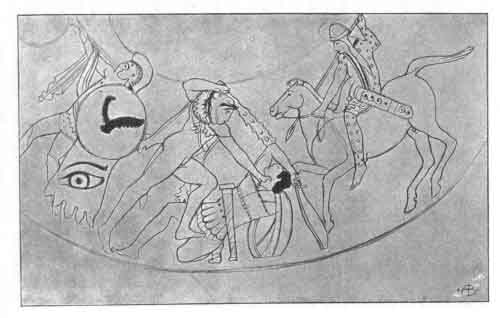

HYDRA (PITCHES) COMBAT OF HERCULES WITH AMAZONS. HAMILTON COLL. BRITISH MUSEUM.

To most, if not to all, of the tales that the Spaniards gave a willing credence there was a solid substratum of truth. The splendid build of the Caribs, the abnormal proportions of the men down in the terrible Tierra del Fuego, and the dwarfish tribes of the forest regions and of the degenerate Aztecs, would account for the giants and pigmies of whom so much was heard. In such matters the terms are essentially comparative to both questioner and questioned, and, moreover, the "little men" term may be relative not only to their stature but to moral qualities also. To the hard-fighting, hungry Carib the man of peace was unquestionably a "little man" no matter how tall or broad-shouldered he might be, just as to-day in the East the mass of people without influence are "little men" to the rulers and their satellites. Even the men with their toes pointing the wrong way (of whom the world had heard before from the early Greek writers on India) existed, for the reversing of moccasins or other feet-covering is a natural dodge adopted to bewilder, and the attempted explanation of such a trick would be quite sufficient to make confusion worse confounded.

Nor need we have a moment's hesitation in crediting the existence of tailed tribes, for totemism and the respect that comes of fear inspired by wild horned beasts was quite sufficient to make man proud of caudal appendages and to supply his own deficiencies in this matter. Even Hercules so managed the draping of the lion's skin about his own body as to secure a very fine tail. Dionysus also treated his panther's skin in the same way, while his Seleni sported the tails of giddy goats with waggish effrontery. In most parts of Africa the buffalo's tail is an emblem of power, as the horse's tail is in Northern Africa and Arabia, whether carried in the hand or worn pendant behind from the waist, the latter method of personal adornment applying to the buffalo's tail, and is found to prevail in the south, east, and west.

Lord Hindlip, writing of the Kavirondo tribes in British East Africa, says the women are fond of a certain amount of adornment, and that "a peculiar ornament is a grass tail tied round the waist generally by a string of beads. I believe," he adds, "that this is an emblem of marriage, and to touch one of those tails is a breach of good manners, the offender being liable to a fine of five goats." Bruce and Baker also mention women in the far Sudan and in the Upper Nile Valley wearing tails of plaited skin or of string. In North America certain ceremonials include the Buffalo Dance, when every "brave" carries horns on his head and a tail waggles fiercely in the rear during the saltatory performance. Both the men and women of the Aymara Indians of Peru and Bolivia wear their hair long and plaited into tails, hence it was supposed that they had originally emigrated from China, or at least been influenced by a Chinese invasion prior to the Inca era. To all these, tails are of no small importance, and would be looked upon by their neighbours with awe or contempt according to tribal relations.

It is in this spirit that most of the Amazon stories must be treated. At the same time, we must not omit to quote some weighty opinions pointing to a more direct acceptation. De la Condamine, who was a thoroughgoing believer in the American Amazon nation, argued that its evolution was quite natural and a development for which we might have looked with confidence. He held that the women leading migratory lives, often following their husbands to war, were usually compelled to submit to very harsh domestic conditions. But the very conditions imposed upon them by their mode of life afforded ample opportunities for them to escape from the tyranny by simply detaching themselves from the tribe and forming a community wherein, if they did not exactly gain independence, they would no longer be slaves and beasts of burden. This method of establishing new communities was, he pointed out, going on in every colony where slave-holding was tolerated; the slaves growing tired of ill-treatment escaped to the forests or swamps, setting up their own camps and villages. Robert Southey re-echoed this opinion that "the lot of women is usually dreadful among savages. . . . Had we never heard of the Amazons of antiquity, I should, without hesitation, believe in those of America." To him the terrible hardships of the Indian women's lives demanded some such relief, and he looked upon the existence of such communities as redounding to the credit of humanity, showing that there was hope for its regeneration. A recent writer of deep philosophic tendencies, Mr. E. J. Payne, follows on the same lines. He regards the whole phenomena of Amazonian states as a perfectly legitimate and understandable outcome of the transition from savagery to barbarism, a period when life is peculiarly harsh to womankind. But, as he says, such communities always carry within themselves the seeds of decay, for they cannot extend, cannot indeed exist for long, without the tolerance of man. A day comes when he grows tired of a complacent attitude, and the women then have nothing to do but surrender on his own terms. These are undoubtedly both interesting and plausible theories, which do not really enter into conflict with the opinions that we have ventured to advance on the whole subject.

Footnotes

149:1 A point not noted by the American Orientalists is that Kamas, the Hindu god of love, is often shown astride a parrot, and was probably originally a parrot god. In Hindu stories the parrot constantly intervenes in amatory matters. It is curious to approach this bit of Hindu mythology with the Amazon legend and its romantic application. But for our own part we see in this only another instance of close observation of facts, in this case the peculiarly demonstrative affection most parrots have for their mates, which may even be carried further, as in the tale of the bird mourning and longing for death because the tree which had given it shelter had withered away. It is, in fact, an example of natural spontaneous symbolism.

Next: Chapter IX: The Amazon Stones