The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER IV

AMAZONS IN FAR ASIA

AMAZONS as portrayed for us by the Greeks belonged, at all events in the fulness of their development, to Asia Minor, we might almost say to Pontus, yet traditions of their excursions to the Farthest East existed. Certainly the idea of the woman fighter and the female community is very generally diffused.

As for the women of the Thermodon, while many held that the remnants of the Themysciran hosts had wandered beyond the Tanais, there were long persistent rumours of their having taken refuge in the fastnesses of the Caucasus, and having made their way thence to Persia, Tartary, and the east. Thus some of those writers who chronicle the visit of Thalestris to Alexander when he was in Hyrcania suppose that she may have belonged to an Asiatic offshoot from the Caucasus, whence the tribe had spread yet farther afield. However, the more we journey eastward the less easy does it become to distinguish between the migratory and the local legends.

Mountains and forests seem to have been the favourite places of refuge for the Amazons, the great alluvial plains the seats of their growth and power. But we also discover a widespread tendency to locate their colonies on islands, partly, no doubt, on account of their remoteness, though, as we shall endeavour to prove, largely owing to more or less clear observation often obscured by too sweeping deductions. While we find the early Portuguese voyagers and their competitors placing a colony of these women in Socotra or some island, or islands, off the southeast coast of Africa, Marco Polo, the Venetian traveller, who wrote late in the thirteenth century, tells us of certain dual islands off the coast of India. He says: "When you leave this kingdom of Kesmacoran (Mekran), which is on the mainland, you go by sea some 500 miles towards the south, and then you find the two islands, Male and Female, lying about thirty miles distant from one another. The people are all baptized Christians, but maintain the ordinances of the Old Testament: thus when their wives are with child they never go near them till their confinement, and for forty days thereafter. In the island, however, which is called Male, dwell the men alone, without their wives or any other women. Every year when the month of March arrives the men all set out for the other island, and tarry there for three months,--to wit, March, April, May,--dwelling with their wives for that space. At the end of those three months they return to their own island, and pursue their husbandry and trade for the other nine months. . . . As for the children which their wives bear them, if they be girls, they abide with their mothers; but if they are boys, the mothers bring them up till they are fourteen, and then send them to their fathers. Such is the custom of the two islands. The wives do nothing but nurse their children and gather such fruit as their island produces, for their husbands do furnish them with all necessaries." All of which offers a striking contrast to the social economy usually attributed to the Amazons. Instead of the women being trained and equipped for warfare, we have a peace organisation, so that the whole appears to us little more than an exaggeration of common facts.

We are told that these people lived on flesh and rice; that there was plenty of ambergris cast up on the shores; that the men were excellent fishers; and, moreover, that they dwelt in islands far from the mainland. Now, under such conditions as these, in a small community, the men would probably be away from home at regular seasons for months together, pursuing their avocations of rice cultivation, fishing, and barter, and then the home island would be populated chiefly, if not entirely, by women and children. Added to this a possible adherence to Old Testament law (Marco Polo says that the islands had a bishop who was subject to the Archbishop of Socotra, whose Christianity would, no doubt, be somewhat akin to that of the Copts), or some analogous heathen custom, and we have a perfectly comprehensible explanation of the story. To this day we can easily discover innumerable "dual" colonies of this description during such seasons as local industries make migration on the part of the larder-fillers imperative. But the Venetian's story, taken literally, was a fruitful source of many embellished yarns, which long beguiled a wonder-loving world.

Marco Polo, it must be confessed, was merely taking up the running, for the legend, in one form or another, is extremely old. Hiuen Tsang is one of the best known of these raconteurs. He was a Chinese Buddhist priest, who spent fifteen years of' his life, between 629 and 645 A.D., in a pilgrimage through India. Probably he is the greatest traveller who ever visited the land and recorded his experiences; for he passed through the country from Kabul to Kashmir, to the mouths of the Ganges and the Indus, from Nepal to Kanchipura, near Madras, and was only deterred from sailing over to Ceylon owing to the disturbed state of the island following on the recent death of the king. Although Hiuen Tsang did not visit Ceylon, he gave a quaint account of its early history. He reports that in the distant ages a certain boy and girl were born on the mainland, their mother being a princess and their father a lion (shall we say, the result of a mésalliance between a rajah's daughter and some doughty chieftain of a forest-robber race?). After many adventures that hardly concern us, but including the slaying of the man-lion by his son, the youth and maid are cast adrift in two boats. The boy landed in Ceylon, which was so rich in gems that it was henceforth to be known as the Isle of Precious Stones. The sister found herself high and dry on another part of the island, and becoming acquainted with evil spirits, brought forth 500 daughters, who were rhackshasis, or female demons who lived on men's flesh. These rhackshasis were extremely beautiful and lived in a magnificent fortress of iron, over which floated a magic flag, which quivered voluptuously in the breeze when luck was to befall the community, but drooped when disaster threatened. To this castle surmounted by its piratical signal the bewitching women lured men, who, after a brief dalliance as soothing as it was delusive, found themselves incarcerated in dungeons, there to await their turn to form a meal for their lady-loves.

A fatal day came, however, when the rhackshasis cajoled a party of rich merchants to their gorgeous home. All unconscious, the men played their part, little guessing the fate reserved for them. But by chance the leader of the trading band, wandering about the fortress precincts, approached a dark spot, and was attracted by piteous lamentations. Investigating the matter, he was horrified to learn that the dungeons were filled with men, who once had sported with the dames, but now awaited a terrible doom. There was, however, hope for the men who were yet free. The prisoners had learnt too late that on the seashore there dwelt a divine horse, who, if sufficiently implored, would ferry the beseechers across to the mainland. So without a moment's delay the merchant gathered his companions, and all turning their faces shoreward, prayed the horse to help them. Thereupon the equine divinity appeared, and bidding them cling to his mane and never look back, plunged into the sea with his living load. It was not a moment too soon, for the women, missing their male companions, rushed to the water's edge, and weeping aloud, called on their lovers to return. Seeing that this had no effect, they picked up their baby sons and flew through the air, crying and beseeching all the way, and finally landing where the horse landed. But on the mainland they were powerless, the men remaining deaf to their appeals, blind to their blandishments.

Then the queen rose in the air and flew straight to the home of the leading merchant. There she told a sorrowful tale of her marriage to the precious son of the house; of his departure for unknown lands and the arrival of tidings of his death; and of her utter despair at being left in poverty with her fatherless boy. As they wept over his suffering, the parents of the missing man took pity on her, giving her shelter. Then the merchant returned, and refusing to listen to the rhackshasis, turned her out of doors, whereupon misfortunes quickly overwhelmed the house. The king of the land, hearing of the wonderful beauty of the strange woman, and welcoming her to his palace, turned his wrath upon the unfortunate merchant. Disaster upon disaster followed, involving all concerned, and the kingdom was in a sad plight. When matters were at their worst, the king was met by the divine horse, who opened the monarch's eyes to the kind of creature he was harbouring. The rhackshasis was seized, a great army assembled, and Ceylon was invaded, the demon women--who had given up in despair when they saw their enchanted flag hang disconsolate round the staff--being destroyed.

An earlier pilgrim, Fa Hsien, another Chinese Buddhist priest, who lived in India for a space of fourteen years, only returning home in 413 A.D., actually visited Ceylon, and calls it the Land of Lions, which is interesting in view of the preceding legend. Fa Hsien too heard faint echoes of some prehistoric period, and reported thereon that the island was originally inhabited by "devils, spirits, and dragons." Even in those early days, at a period anterior to the advent of Buddha, merchants from the mainland traded with the uncouth islanders, though the devils and spirits did not appear in person. Their methods of dealing were far more delicate than the usual market-haggling, for they trustfully spread out their goods on the shore, duly ticketing each piece or heap with the price they should fetch, and the merchants, having made their selections and deposited the exchange value, departed. These, indeed, must have been tolerably bons diables, and probably their rhackshasis nature only made itself manifest when the wily Hindu or his precursor proved but indifferently honest. To the more civilised mainlander the small black island aborigines would appear uncanny "devils," though profitable trafficking might be carried on with them. This would be difficult enough owing to their extreme wildness and the timidity of the forest and mountain folk, who moved about like will-o'-the-wisps, and only became formidable when ill-treated or robbed. On the other hand, the feminine arts brought to bear on the visitors, who would be susceptible in spite of their cupidity, would naturally be attributed to sorcery, and the whole story ultimately assume the picturesque and marvellous form in which it is presented to us by Hiuen Tsang.

These Ceylon rhackshasis, although of local parentage, are merely a variant of the vampire women so commonly met with, at least in the realms of fancy, and of whom Circe and the Syrens are types, and whose analogues may be found in Norse and Teutonic mythology. Of the early eastern exploits of the Themysciran Amazons we are told in connection with the legends of Dionysus, that protean hero-god who represents spring-tide and the arts of husbandry, more especially the wealth of the vine. Of him, it must be remembered, the poets say that this "twice born" was brought up at Nicæa, went to the rescue of his father Jupiter in the war against Saturn and the Titans, sharing in the success, aided, some say, by the valiant Amazons. With them he went through Asia as far as India, and on his way back took in Egypt as part of his conquest. Dionysus of the earlier Greek fables was a handsome youth. Then we know him as a beautiful hero, glorying in his eastern exploits and bringing back the vine, which had been destroyed during the Deucalion deluge. Wherever he went, and was received, he brought with him prosperity. His Amazonian guard appears to symbolise his sterner aspects. Undoubtedly it was this phase of the myth that was uppermost in the minds of many observant travellers in India. For instance, Niebuhr, describing the rich profusion of carvings on the rock-hewn-temples of Elephanta, says: "One woman has but a single breast, from which it should be seen that the story of the Amazons was not unknown to the old Indians." He gives a picture of this supposed Amazon, of which many examples may be found scattered up and down India wherever Brahmanical influence has made itself felt. The truth is, this is no Amazon, but the mighty Arddhanarishwara, representing the union of the "moon-crested" god Shiva with the female principle Uma, or of his wife Parvati. Many are the stories, full of philosophical meaning, told of this dual personality, teaching that the complete life cannot be one-sided, the sexes being interdependent. It is a sermon in stone telling of life and toleration, and, therefore, is in exact opposition to the warnings conveyed by the original Amazon myths; also differing from the Talmudist account of Adam's first appearance as a man-woman of monstrous size and a terror to the angels. Both the eastern allegories tell of the unity of nature, though they travel along divergent roads. Yet, united and separate, the Indian mystic duality are not without their grimness, for they represent the great natural forces and the supernatural and their unfathomable workings. Shiva is "he of whom growth" (increase, prosperity) "is," the "wearer of the eight forms"--that is, the personification of earth, water, air, fire, ether, the sun, the moon, and sacrifice. Parvati is the universal, the nature goddess. The religious books say that Shiva and Parvati were one in body, united like the word and the sense.

According to one of the Puranas, Arddhanarishwara, sprang "full armed," like another Pallas Athene, from the wrinkled brow of Brahma the Creator, who ordered a division, so that Shiva and Parvati came into separate existence. In another of the Puranas we find that after marriage Shiva and Parvati lived on Mount Kailasa, where the wife kept house and the divine husband supported his family by begging. But Shiva smoked too liberally of the intoxicating herbs, and neglected his task of mendicancy, whereupon Parvati reproved him, sent him forth to beg, and then carried off their children to her father the Himalayas. But repenting, she assumed the form of Anna-purna, goddess of food, and laid an embargo on all eatables in any house where Shiva sought charity, so that he was sent empty away. On reaching home, the famished and disheartened Shiva was welcomed by Parvati with smiles, and she bestowed food on him. Then he embraced her, and they became one. Whatever the version, the lesson of toleration and interdependence is laid down.

In the Elephanta carving the differences of sex are given great prominence with true Oriental love of exaggeration. The figure is 16 feet 9 inches high, the right side being Shiva, the left Uma. Each half has two arms. In the case of Shiva, the back hand holds up one of his most venerated symbols, the hooded cobra, while the other rests on the head of Nandi, the sacred bull steed. Dr. Wilson declared that it represents not the domesticated bullock, but the wild bos gavæus of the forests, which goes far to prove the antiquity of these carvings, or of their prototypes. The head-dress is of the usual high and much-decorated pattern. On the right is the crescent, and under the cap the hair is represented by a series of little knobs; on the left two heavy folds descend to Uma's shoulder, and the hair is shown in rows of neat ringlets. Uma holds up a large mirror, which Niebuhr and others, with their notion of Greek influence, mistook for a small round shield. The feminine side of Arddhanarishwara, is, therefore, distinctly associated with the arts of peace, not with those of war or governance.

It is curious that the Latins of the third century of our era possessed a truer account of those carvings than we did in the eighteenth century. A part of Porphory's lost treatise De Styge has been preserved, and this relates to the questioning of certain Indians who came into Syria during the reign of Heliogabalus. These Indians spoke about a vast natural cave in a lofty mountain. "And," said they, "in this cave there is a statue which was about ten or twelve cubits. It stands upright, with the hands extended in the form of the cross. And the right of its face is that of a man, while the left is that of a woman. Now in the same way the right arm too, and the right foot, and the whole half are of a man, and the left of a woman: so that on seeing it we are astonished that we can see the dissimilarity of the two sides in one body without division. In this statue, they say, are carved round the right the sun, round the left the moon; and down the two arms are cleverly carved a number of angels and all the things that exist in the universe--that is, the heaven, the mountains and the sea, and the river and ocean, and plants and animals, and, in a word, all things that are. This statue, they say, God gave his son when creating the universe, that he might have a model." They also declared that the statue sweated in summer unless fanned by the priests; but we must remember that originally the statue was painted black or blue on the right, vermilion on the left, or yellow and white, and this painting may have had something to do with the phenomena, The angels and other decorative accessaries are not on but behind the statue. This divergence may be due to a misunderstanding on the part of the interrogators, and so with a few other inaccuracies. But the particulars given seem to point clearly to Elephanta, and if this is so, then we have evidence of a much earlier date than the tenth, or even the eighth, century, which modern students of Indian antiquities are inclined to assign to the carvings. It will be seen that the pilgrims from India gave their Roman questioners a true notion of the elemental and religious character of these carvings, which had nothing to do with any Amazonian polities.

Nevertheless, warlike women were well known in India. We hear of them from Greek sources by way of Megathenes, who was there as ambassador about 300 B.C. On the death of Alexander in Babylonia, one of his successful lieutenants who struggled to grasp the Eastern power usurped by the great Macedonian was Seleukotos Nikador, who ultimately became master of Babylonia, Bactria, and lord of Western and Central Asia. But when he reached India, he found himself confronted by a powerful native chief, who, revolting against the Greek and other foreign governors, had assumed imperial power, with his seat of government at Pataliputra (modern Patna). This Indian, whom the natives knew as Chandragupta Pataliputra, and the Greeks called Sandrokotos, was, by his father's side, a descendant of an ancient royal house of Northern India, but his mother had been of low caste, and consequently he was of the people too; but royal traditions were strong within him, and old customs would be purposely fostered in order to revive well-known forms as against the innovations introduced by the Greeks. After Seleukotos had been repulsed, he sent Megathenes as his ambassadar to Pataliputra, and it is mainly from fragments of his accounts that we derive outside knowledge of India and Indian ways. He reports that Sandrokotos dwelt practically isolated in his palace, surrounded by an inner guard of armed women. Vincent A. Smith says that the rajah's prime minister, Chanakya, prescribed that "on getting up from bed, the king should be received by troops of women armed with bows." It was a tradition that under certain circumstances these women were at liberty to slay the king, and the slayer married his successor. This personal guard of the king attended him when he appeared in public. When he went hunting the guard of women was quite numerous, some riding in chariots, others mounted on horses and elephants, and all equipped with weapons as though they were going on a campaign.

Both the levee and the hunting retinue are very ancient institutions which are frequently referred to in native literature. Talboys Wheeler, in his account of ancient Indian plays, says that the first act of Sakimtala (written by Kalidasa about 56 B.C.) opens in a forest where the rajah appears in a chariot carrying bows and arrows and surrounded by women wearing garlands, but also armed with bows and arrows. Sir Richard Burton mentions that many native princes, especially those of Hyderabad and the Deccan, maintained female guards called urdu-begani or "camp captains." Then there is the well-known instance of Ranjeet Singh of Lahore, who had a bodyguard of Amazons, 150 strong, recruited from the loveliest girls he could procure from Cashmere, Persia, and the Punjab. They were richly dressed, armed with bows and arrows, and mounted on milk-white chargers. These were merely troupe de parade, but they represented the historic royal bodyguard of a past age. At Lucknow there was a strong guard of female sepoys kept within the palace precincts. The same custom prevailed at Hyderabad, as we have already said, down to the middle of the nineteenth century.

Travellers give us lively accounts of these female troops, gaudily uniformed in scarlet tunics, green trousers, and red cloth caps trimmed with gold lace and great green plumes. They carried muskets and swords, and paraded like other troops, apparently being officered by men. We hear more than once of their taking a sanguinary part in palace cabals and dynastic upheavals, queen-mothers leading reactionary factions to power by the aid of the women soldiers. Although small and slender, these Hyderabad damsels in war panoply were often mistaken for ordinary male sepoys by casual visitors to the palace, for they cultivated a man-like bearing. No doubt these armed women were connected with the safe-keeping of the harem; but for their origin we must go much farther back, and in this connection it should he remembered that the rajah of old was a sacred personage, a demigod. Thus the Ramayana, which appears to have been reduced to writing in the fifth century B.C., but was much older, recounts the adventures of Rama-Chandra, an incarnation of the god Vishnu, born to Dasaratha, King of Aysdha (Oude), himself a descendant of the sun god, who was grandson of the Creator, Brahma; while the ancestor of the Pandavas, the heroes of the more celebrated Maha Bharata, was Chandra, the moon god of Northern India. Now, this is particularly interesting; for though we have seen reference to an Amazonian colony in Ceylon, the earliest and most deliberate mention of such a phenomenon appears in the Maha Bharata.

This, like the earlier Ramayana, was originally a collection of religious and dynastic ballads dating back, according to Mounstuart Elphinstone's calculations, to at least 1500 B.C., and telling of the great deeds of the house of Bharata, the rules of an Aryan race. Later, however, the Brahmins annotated and converted the great epic into one of their own sacred books, in which the religious and moral teachings are embodied, though much of the older Vedic and pre-Vedic customs still remain in the voluminous poem.

The story opens in the city of Hastinapur, northeast of modern Delhi, on the upper banks of the Ganges, and is largely concerned with the doings of the exiled Pandavas, the rightful princes, who are banished by their uncle owing to the intrigues of their aunt. Perhaps the chief hero is the youngest prince, Arjuna, who interests us especially because the Maha Bharata gives a detailed account of an Aswamedha, or horse sacrifice, organised by him. We will follow Talboys Wheeler's analysis as far as it concerns our present purpose. The Aswamedha was at once a religious rite and an empire challenge. A horse having been carefully selected by the rajah, elaborate ceremonies followed, and the challenge engraved on a metal plate being fastened on the horse's forehead, it was turned loose. For the space of a whole twelvemonths the horse was permitted to wander whither it would, followed closely by the rajah and his retainers. If the horse trespassed on an adjoining state, the reigning rajah had but two alternatives: to seize it and place it in his stables and offer battle in its defence, or he might capture the horse and return it to the roving rajah with all due submission, which was tantamount to an acknowledgment of vassalage. In such circumstances the horse would go far and wide, and if all went well, at the end of the year it was conducted back triumphantly to the capital, where, in the presence of the conquered or submissive rajahs, it was ceremoniously sacrificed to the gods, amidst plaudits and songs in praise of the wanderers.

In the Maha Bharata we are told that Rajah Arjuna, after performing many gallant deeds and various sacrifices, decided upon the Aswamedha. Leaving Hastinapur, the horse leads the party into many strange places and formidable adventures. In the fifth stage he enters a country inhabited by women only, ruled over by Rani Paraminta. Now, the custom of this country was for the women, who were very beautiful and belonged to the rhackshasis class, to receive men, entertain them kindly, and retain them by their sides by their artful wiles; but if the men remained over a month (and there was little hope of their escape from the vigilant guard), they were killed. And those women who had harboured them and were not with child committed satti. In this manner was the nation kept ever young. When Arjuna reached this country, or rather was led there by the sacred horse, he fell into great perplexity. Turning to his followers, he said, "This is a marvellous country that the horse has led us to. If we conquer these women, we shall obtain no credit thereby; but if we are conquered, our disgrace will be greater than can be conceived. Moreover, these women are of great strength, and whoever lives with them for a month is a dead man. They will now seize our horse, and we shall find it hard to stand against them." As they pondered deeply, oppressed by gloomy forebodings, a brilliant cavalcade appeared. The women warriors were of dazzling loveliness, all between fifteen and sixteen years of age, mounted on superb horses, gorgeously dressed and adorned with pearls round their necks and arms, while they carried bows in their hands, and quivers full of arrows hung from their waists. Promptly they seized upon the Aswamedha horse and conveyed it to the rani, who ordered it to be taken to her stables, there to be kept as an extra charger.

Then the rani sallied forth mounted on an elephant and surrounded by her cavalry. As the opposing forces met, Rani Paraminta cried out, "Oh, Arjuna, you who have triumphed over so many men, can you conquer me?" and so saying, she shot a single arrow with such sureness of aim and such strength that the men stood amazed. "I myself will take you prisoner. You must abandon this unprofitable Aswamedha sacrifice, become my slave, drink with me, and pass your time in pleasure." "Yet, oh, rani, if I remain, I die," answered Arjuna. "In either case you are helpless. If you resist me, you fall by my arrows; if you remain, you have to face the light of my eyes." Then Arjuna confessed himself conquered, for he felt himself in love, captivated by her skill and her beauty. But he appealed to her superior understanding: it was impossible for him before gods and men to abandon the Aswamedha sacrifice; once commenced, it must be persisted in while life remained. He would carry out his task; then, if she would go to Hastinapur, on his return he would marry her and find gallant husbands for all who accompanied her. To this the rani replied that she had intended to kill them all; however, that which the rajah had said pleased her. She was willing to return the horse, even to hasten off to Hastinapur and there await Arjuna's glorious return. So she departed, surrounded by her cavalry, with a vast array of elephants loaded with treasure in her train. Which was, of course, an act of submission in accordance with the rules of this curious war game.

It is unnecessary to follow the adventurers through all their intricate windings to the happy ending, for our concern is with the women, but we may mention, as having a bearing on one aspect of our inquiry, that the horse took the wanderers to a forest where men and women grew on trees, flourishing for a day and then dying, and also to a land of serpent-worshippers. It is possible that this race of warrior women may have had some reference to the peculiar customs and warlike habits of the Nais women of the mountainous regions on the Malabar coast, though it seems to point to traditions of a peculiar state of affairs in some dim past. One point is to be noted: unlike the Greeks, who held their wars against the Amazons as amongst their most splendid feats of arms, the Indian prince holds quite another view, although he dreads both their strength and their snares. Probably the Brahmins have moralised the tale, with a view to show that the prince only escaped disaster by resisting allurements and bringing the adventure within religious bounds.

Both the Ramayana and the Maha Bharata describe India as a land where towns were few and far between, a land mostly covered with dense forests, inhabited chiefly by two classes of folk--the ascetics, who dwelt in seclusion, piling up treasures of power by prayer, observing austerities, and offering sacrifices; and by evil beings, who opposed holy hermits, dealt in magic, and were mostly cannibals. Many of the latter were women of the rhackshasis class, against whom Rama and Arjuna offer frequent battle.

Palladius, Bishop of Hellenopolis, in his De Gentibus Indiæ, writes of another order of affairs, for he says that the Brahmin men in the valley of the Ganges lived on one side of the river and the women on the other, the husbands visiting their wives for forty days in June, July, and August, but that when a child was born the husband never returned. Here, again, we seem to have a garbled rendering of the two phenomena, the long absence of men from their villages during seasons of work, and the segregation of the sexes during certain periods not altogether unconnected with physiological reasons and religious observances resulting therefrom.

Of the state where men were ruled over by women we have a hint from Hiuen Tsang, who says that on the northern borders of the Bramaputra he found the kingdom of Kin-chi ("of the golden family"), which was governed by a queen. Her husband was named king, but he did not rule. We are not told whether this was customary, or merely an accident due to a weak consort mated to a domineering ram, but the Chinese philosopher rather conveys the idea that this was the normal condition of affairs.

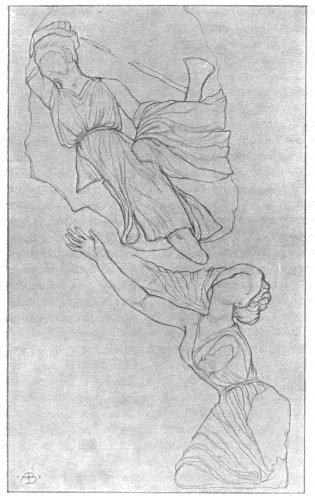

FRAGMENTS FROM MONSOLUS FRIEZE

(BRITISH MUSEUM).

We hear of Amazonian isles much farther east. In the Arabian Nights the story of Hsan el Bassorah tells of his love for a beautiful and mysterious lady, who after their marriage and birth of children flies off to the island of Wak-Wak, thus having some analogy with the charming Lilith, according to the Talmudists Adam's first wife, who, having peopled the earth with devils, flew away to mate with Satan and beget the whole legion of jinns.1 Hasan's wife, we are told, was the daughter of a very great king, who ruled over men and jinns. He had an army, 25,000 strong, of women, "smiters with swords and lungers with lances," any one of whom when mounted on a swift steed was equal in valour to a thousand knights. This king had seven daughters, who were braver and more expert than their 25,000 "sisters." The eldest of these seven, who "in valour and horsemanship, and craft and skill, and magic excels all folk of her dominions," was Hasan's wife and queen of Wak-Wak, the furthermost of a series of seven isles, whereon there was a forest near unto Mount Wak, where the trees bore fruit with the faces of the sons of Adam, who cried, "Wak-wak, glory to the Creating King," as soon as the sun rose, and again, "Wak-wak, glory to God," with the setting of the sun.

Lane in his notes to his translation says that the island of Wak-Wak, or El-Wak-Wak, well known in tradition and chronicles, appeared to be near Borneo. It was a land governed by a queen surrounded by troops of beautiful women. Gold was abundant, and the trees brought forth women, who hung by their hair from the branches, crying "Wak-wak," and when their hair was cut they died! An Arab author, Ibn-el-Wardee, quoted by Lane, mentions an island of women in the same sea in which there were no men. Mendoza, the historian of China, heard of two islands, a male and a female, like those of Marco Polo, off the coast of Japan; and it is curious that Professor de Goeje, as Sir Richard Burton informs us, heard Japan spoken of in Canton as Wo-Kwok. Burton in his notes on the tale of Hasan holds that the Arabian geographers spoke of two Wak-Waks. He quotes the French translation of Ibn-el-Fakih and Al-Ma’udi, who locate one of the islands in East Africa beyond Zanzibar and Sofala.

On the other hand: "Le territoire des Zendjs commence au canal (Al-Khali) derive du Haut Nil et se prolonge jusqu'au pays des Sofalah et des Wak-Wak." Which Burton says is simply the peninsula of Guardefui, conquered by the Gallas before the Moslem Somals swept them away. The pagan Gallas continually called out "Wak" like the Moslems cry "Allah"! "This identification," continues Burton, "explains a host of other myths, such as the Amazons who, as Marco Polo tells us, held the Female Island. The fruit, which resembled a woman's head (whence the puellæ wakwakieness hanging by their hair from trees) and which when ripe called out 'Wak-wak' and 'Allah al Khallak' (the Creator), refers to the calabash trees, that grotesque growth, a vegetable elephant, whose gourds, something larger than a man's head, hang by a slender filament." The second Wak-Wak has been variously identified with the Seychelles, Madagascar, Malacca, Sunda, Java, an island off Sumatra, an island off the coast of Japan, and even far-off New Guinea, the latter because there flocks of birds of paradise settle on the trees and call out "Wak-wak-wak." Other authorities tell us that to the south of China there was a maleless island, where the women mated with the winds; while the patriarch Bermudes refers to an island in those waters inhabited by Amazons, who, in the usual way, only received men at stated seasons, keeping the girls born to them and sending the boys to their fathers. Then, as Pinkerton tells us, the Jesuit missionaries heard of similar islands from inhabitants of the Marianne Island, these rumours referring to one of the same group, the Ladronnes of evil repute, or to the more southerly Carolines, of which like tales were told. So vague, however, was all this, that it may with equal possibility apply to one fabled isle, floating in indefinite seas, roaming now here, now there, according to man's credulity and ignorance, or to certain abnormal social conditions cropping up again and again in many localities, far apart on the face of the waters as well as in time. And this brings us back to the Far East.

Certainly in this Farthest East not only the traditions, but the actual existence of Amazon guards may be traced to within our own times. In the early seventies of the last century there were women palace-guards at Bangkok, on the same lines as those at Hyderabad. And at the same period in Bantam, which then held an almost semi-independent position under the Dutch, the king had a royal troop of women soldiers, who rode astride and carried muskets and lances. It was said that if the king died without a direct heir, the Amazons met and elected a king from among their own sons. Sir Richard Burton points out that Tien-Wang, the Celestial King of the Tae-Pings ("Princes of Peace"), had a bodyguard of 1000 women soldiers. Now this is particularly interesting, because Tien-Wang had headed a formidable rebellion against the reactionary Tartar Emperor of China in 1851, and calling himself Tien-Teh (Celestial Virtue), declared that he was the restorer of the true God, second son of God, brother of Jesus, sovereign of all beneath the sky, true lord of China. This universal monarch and his misnamed followers accomplished great conquests, and would probably have made themselves masters of China had not Gordon intervened, bringing about defeats and the capture of Nankin in 1864, whereupon Tien-Wang committed hari-kari. His followers for the most part escaped into Tonkin, where they were long known as the very troublesome Black Banners and Yellow Banners. The momentous point in all this is the dual claim to sovereignty made by Tien-Wang, as a divine personage and a world-monarch, and his surrounding himself with female guards, which connects the Chinese religious reformer sociologically not only with the princes of the Deccan, but, as we shall presently see, with the dusky rulers of the Upper Nile and the west coast of Africa.

Footnotes

81:1 This was, no doubt, an attempt on the part of the Talmudists to account for the worship of demons by the early Hebrews.