The Amazons

by Guy Cadogan Rothery

CHAPTER X

CONCLUSION

EVEN when divested of adventitious adornments, there remains a remarkable body of evidence as to the widely prevailing belief in the existence of countries, districts, or islands populated solely by women. Such a phenomenon cannot be entirely ignored by the student of human nature, and is, indeed, worthy of some painstaking inquiry. From the very outset it is clear that the Greek myth is not sufficient to account for all the stories, though it is, of course, indisputable that these legends have largely coloured most of the tales that have reached us. But that narrow and somewhat egoistic view which sought to trace back everything to Grecian influence is quite inadequate to explain the traditions found to exist in every quarter of the globe. We cannot admit the theory that these legends or customs have been spread by migrations. Nor can we accept the ideas put forward by Robert Southey, Sir Clement Markham, and Mr. E. J. Payne to the effect that the hardships imposed on women in savagedom caused revolts resulting in the formation of feminine "tribes," living apart, fighting, and only having voluntary intercourse with men, as an all-embracing explanation. We must seek deeper than such theories as these will take us.

It is possible to divide roughly the legends and traditions into three main classes. We have: (1) Women living apart in colonies, but having occasional communications with the outside world on a peaceful footing. (2) Women banded together as a fighting organisation. (3) Nations ruled over by queens, and mainly, or to a considerable extent, governed by women. Varied as are the stories which we have reviewed in the foregoing chapters, it will be seen that they all fall into one or other of these divisions. Now, if we examine the matter, we shall see that all three are simple outcomes of different stages in social evolution. Of course, we find them often profoundly modified by local conditions. They are so far healthful signs inasmuch as they are different manifestations of life rather than of stagnation, showing a striving after some form of ideal, however benighted, amidst the discomforts of periods of transition. We may see the three stages following each other, by no means always in the same sequence: a hyper-cultivation of one phase or another, frequent blendings, and much irregularity of survival. Which is quite what might be expected if we accustom ourselves to look upon the phenomena as usually the spontaneous outcome of local needs.

It must be admitted that as society emerges from savagedom into barbarism on the road towards civilisation, the burthens of the respective sexes are readjusted, and not without considerable friction and discomfort. Man ceases to be merely a fighting and hunting animal; he becomes the larder-filler in a wider sense. Now, this often involved, and, indeed, does still involve, gathering harvests and collecting foods or food values of one kind or another far from home. Sometimes the whole tribe will move from winter to summer quarters with this object in view. We find this typified in its most exaggerated form by the nomadic communities. But to go no great distance, we find this kind of thing largely prevailing to this day in Switzerland, in Norway, in certain parts of Italy and Corsica, chiefly, though not entirely, among shepherds and cattle-keeping folk. But often enough it is the men alone, with the growing lads, who go off on active work, leaving the homes to the safe-keeping of the women, with a sprinkling of old men and small boys. Corsica offers a curious combination of phenomena bearing on this point. First, we find that there is a winter migration of the shepherd people from the interior to the coast villages, and a summer migration away from the malarious coast to the mountain villages and grassy slopes, which often leads to a strange numerical inequality of the sexes in the different villages. Secondly, the island is annually invaded by a swarm of Italian able-bodied men and youths, chiefly from the districts surrounding Lucca, who come to till the vineyards and do other heavy agricultural work which the native Corsican deems beneath his dignity. Thousands of the Lucchessi come, generally in squads of five, remain for about three months, and then return to their homes. They invariably arrive without their womankind, so that their villages practically become feminine communities during these regularly recurring periods of absence.

A similar state of affairs is known to have existed among many tribes of the Caucasus. Quite late in the day Father Lamberti found that the Suani men, a brave, strongly built mountain tribe, and extremely poor, came down every summer to work in the plains at the foot of the Caucasus, taking back to their families in their isolated homes food, copper, and certain other raw materials for their modest industrial enterprises. Fishing as an industry frequently leads to the same conditions; indeed, even now during the herring season temporary feminine communities are formed on the coast of Scotland by the fish-cleaners, who remain hard at work dealing with the catches between the visits of the fleets. It is some such natural explanation that occurs in regard to Marco Polo's story of the Male and Female isles, thus coinciding also with what. we gather from Lord Macartney's account of the Zaporavna Cossacks and the Dnieper island. We can easily understand that such conditions, if accentuated beyond the ordinary course owing to local exigencies, would give rise to misapprehension among the ill-informed, or among people of other ways of living, who are by habit of thought and actual training intolerant of any divergence from the normal.

Then, again, these conditions, which exist chiefly among communities living in mountainous districts, forests, and small islands, would lead to developments in other directions. The women would of necessity cultivate the arts of governance and of warfare, for obviously the maleless villages would be more open to attack, and would often call for not merely bravery on the part of the women, but of cunning in the method of defence and counter-attack. Something of this conflict of sentiment and method is revealed to us by Quintus Smyrnus in his account of the struggle between the Greeks and Amazons before Troy. The warrior feeling is expressed by Hippodamia, who, excited by the brave deeds of Penthesilea and her companions, calls upon the Trojan maids and matrons--

"Come, friends, let us too in our hearts conceive

A martial spirit such as now inflames

Our warriors fighting for their native walls;

For not in strength are we inferior much

To men; the same our eyes, our limbs the same;

One common light we see, one air we breathe;

Nor different is the food we eat. What then

Denied to us hath Heaven on man bestowed?

O let us hasten to the glorious war!"

But Theano, "for her prudence famed," deprecates such a move--

"Till the foe hath closely girt our towers

We shall not need the aid of female hands."

Which shows how old these ever-new problems are. Forgotten for a season, they are rediscovered and proclaimed as startling novelties or divine revelations, only to be inevitably brought within the compass of reason by the hard logic of facts, and the Theanos prevails.

No doubt in certain stages of society the whole tribe moves, and the women, especially if of a hardy mountain or forest stock, would naturally share all forms of activity with the men within the measure of their strength, and the more skilful of them would be found in the fighting ranks with the male warriors. Thus it comes about that historians and travellers tell us now of unisex organisations, and then of women in Asia, Europe, Africa, and America--using the bow and arrow, the sling and the lance, aiding and abetting their husbands and brothers in martial exploits.

As we have in effect already observed, the juste milieu is never a strong point in feminine nature, and so fighting woman becomes in very deed an "unholy terror," something particularly abhorrent to those who are fresh from casting off the fetters of barbarism. The ratio between fighting men and women would constantly vary under the influence of seasons or tribal evolution, and so tend to further accentuate error of judgment, giving rise to robust myths.

Great, too, is the influence of religious ideas. Marco Polo says that the dwellers in his dual islands observed the ordinances of the Old Testament. This segregation of women during periods of childbirth may be traced as having been a matter of common occurrence in all times and places. We have much evidence of this among the Hebrews and their neighbours, and also in modern times among races far apart. The Toda dairy folk of the Nilgeri Hills, whose most strange pre-nuptial custom is extremely suggestive of ceremonies attending the worship of Astarte of old and of the Indian goddesses Kali and Durgan to this day, build special huts for expectant mothers, such huts being placed away from the villages and all paths used by man and the sacred herds. They may not join the community again until after having undergone a purificatory ceremony. So too with the Waiknas of the Mosquito coast, a retreat being "prepared for them in the depths of the woods, where they are not allowed to emerge for a stated period--that accomplished, a public lustration of mother and infant takes place." Where moon-worship prevails, this custom is apt to be very much exaggerated, the segregation going right through the tribe, in obedience to the supposed lunar influence on physiological conditions. This idea was at the base of the religious ceremonies in which only one sex could take part, and which we find among barbarians and even the highly civilised Greeks and Romans, but which, in the more primitive states, would cause the sexes to divide up temporarily into unisex tribes. The Amazons of Asia, we are told, were worshippers of Artemis (Astarte), who had her great mysteries only to be witnessed by women, as well as ceremonies in which both sexes mingled in secret and openly.

Fortune of war is another of those important influences which must be taken into account. With both savage and barbarian the slaying of all male prisoners is a common practice dictated by policy more than revenge, and if only the conquest is sufficiently thorough the drastic measures bring about a peculiar state of affairs. Men and women of the Carib tribe were found by the early voyagers to use different languages. The Caribs themselves explained this by saying that they were originally a mainland nation, and that they had invaded the islands and slain all the men, and after a time had married the women. This idea of conquest is also perhaps portrayed in the Maha Bharata by those incidents that we have described. Even more striking is the incident of the siege of Damascus, under Khaled, lieutenant of Abu Becker, the first Caliph, when the Moslem women were surrounded by the enemy and succeeded in beating them off. It is easy to realise that had their mankind been destroyed the plucky dames might have succeeded in securing their retreat to the hills, and there formed a "woman's tribe," which would either have endured for a brief space before melting into the surrounding population, or under stress have been artificially kept up for a generation or two. That ring of tent-pole-wielding Hamzarite women camp-followers affords a perfect example of the accidental formation of such a tribe in the making, though another turn in the fortune of war diverted the probable sequence into a happier channel.

Another phase is more than hinted at in the adventures of the Argonauts in Lemnos, as given to us by the Rhodian Apollonius. Admitting a certain amount of tribal pride and organisation among the women, it is conceivable that the male and female "nations" would be some time before effecting reconciliation and merging into one tribe. But in such cases, as in those where, as we may allow did occasionally occur, the women struggling from savagedom to barbarism went off to form their own camps or "nations," the final result was inevitable, for, as Mr. Payne says, a day comes when the women have to surrender on the men's own terms. An amusing enough illustration of this is taking place in the United States, where, some thirty years ago, a Mrs. M‘Whirter, of Waco, announced that she had been inspired by the Almighty, and told to leave her husband, for it was sinful to live with man. The inspired prophetess found many willing disciples to adopt her creed, abandoning husbands, sons, fathers, brothers. So a new Women's Commonwealth sprang into being; a colony in due course was founded at Belmont, Texas, which was subsequently removed to Washington State. All went well for many years, then came a change, the eligible dames and damsels one by one forsaking their convictions; for, as one of the most recent brides candidly confessed, though "brought up in the belief that it was a sin to marry," when they met the "inevitable he" they were "just crazy over him," and thus the unnatural commonwealth breaks up to-day in America under the influence of the selfsame forces that acted thousands of years ago in Asia Minor.

As regards the alleged difference of languages used by opposite sexes, we must not attach too much importance to the matter, either in connection with the Caribs or any other people, for this state of affairs is often seen to prevail, mainly, it would almost appear, as an anti-matriarchal precaution, "superior" man having his own language for ruling and religious purposes. This is not unknown in the East, and some traces of it are to be found among the Indians of Peru. The ruling classes in all quarters of the globe often used a different language to that of the populace, and not always (as was the case with the Normans in England) as the result of conquest. The Incas had a language in which many words were secretly symbolical: thus Cuzco (or more correctly Cozco) to the ruled was merely the name of the Emperor's capital, but to the initiated it meant the umbilicus, which, having regard to the traditions of the race, was peculiarly significant--a device which has always been of immense service in welding together special castes, priestly classes, secret societies, and kindred organisations involving the observance of vows, with accompanying solidarity of interests, duties, and privileges.

Of the matriarchal stage of civilisation much might be said in this connection. It undoubtedly played a useful part, and must not be thought to have necessarily implied inferiority in the position of man. In fact, it may often be taken as evidencing the peculiarly migratory character of the male, who could not throw off his wandering habits or needs, although developing an unconscious desire for acquiring a "local habitation and a name," if not for himself at least for his offspring, and thus by the safest way in a most primitive society ensuring hereditary proprietorship in "chattels," lands, and totems. Dr. Livingstone found that among the Banyai the wives were the predominant partners, and the children of the unions belonged to the mothers' families. It was only by buying the wives (not an easy matter with them) that the children became the property of the father and his tribal section. Arrived at a certain stage on the road of evolution, such a condition, and all that it implied, would become odious to the male state, though such a feeling need not always be extended to a queen ruling over men, even of a warlike nation. There have been many strong women sovereigns, and we may take instances from one of our Amazon regions: such as the Queen of Sheba, who governed the rich and powerful country as an autocrat. That this traditional loyalty to a queen lingered in the locality we know not only from the Portuguese missionaries of the sixteenth century, but from what happened in the last century during our own Abyssinian Expedition (1866), when the Wallo Galla country, where Magdala was and Sheba had been, was found to be ruled over by two rival and warlike queens, each with a long following of devoted male subjects.

It is not without deep meaning that while the Greeks held their warfare against the Amazons as among the most noteworthy and honourable of their feats of arms, the Indians only dreaded the odium of defeat, looking for no glory as a possible outcome of their fighting the female warriors. Yet the Greek ideal of womanhood was far inferior to that shown in early Indian traditions. The truth is, the Amazons symbolised all that was dangerous to man and State to the Greeks, something to be feared but fought and conquered; while to the Indians it meant merely a different phase of society, to be overcome rather by an intellectual revolution than by force of arms. So while the Greek fought and boasted of his successes, the Indian swept away the unnatural state by force of religious argument, and no doubt persecution. The difference shown in dealing with this troublesome matter (as it was to both) is all the more remarkable because the great Eastern Epic is not without its tales of many bloody conquests both in the military and religious fields.

Reviewing the whole subject, it seems clear that it is to religious influences that we must trace the existence of many, and probably the most startling, traditions concerning bands of women warriors and women societies. It reveals one of the most sombre sides of the human intellect. We have to go to the dark Caucasus to find the origin of the Greeks' Amazons. Here it was that Prometheus, who had stolen fire from heaven and placed divine truths at the service of mankind, was fettered to the rocks, exposed to the torture of the eagle until that bird, the emblem of priestcraft, was slain by Hercules. This was merely a symbolical presentation of what was actually taking place. For here too, as Strabo reveals, the Albanians had a sanctuary dedicated to the moon-god, a temple wherein men were sacrificed by a spear-thrust, the priests watching the fall and gush of blood for purposes of divination, after which the body was removed to a stated spot so that the people might take an active share in the sacrifice by trampling on the scapegoat and purifying themselves thereby. Farther to the north-east, at Phanagoria, near the Palus Mæotis, he also tells us, was a shrine to Venus Apatura, the Deceitful, who, having secured the aid of Hercules, allured her admirers one by one into a cave, where they were killed by the sturdy sons of Jupiter and Alcmena.

It is difficult not to see in this a local tradition with a Greek gloss, for we know how they loved to allegorise facts and to Greecise barbarian gods. Is not Venus in this instance Astarte? that Ashtoreth whom men knew as "Queen of the Heavens" and worshipped in such ghastly fashions as goddess of fertility? And is not Hercules her consort, the great Baal, giver of life and lord of fire, with his club-like thunderbolt? The whole story has the appearance of an allegorical description of some religious mysteries. By one of those peculiar, but easily understandable, workings of the human mind, worship was mainly propitiatory, linked up with the idea of sacrifice, which often led to such terrible conclusions.

Two main notions, it should be observed, underlay the theory and practice of sacrifice: the expiatory act and the propitiatory offering. In an animistic stage of development, the spirit pervaded everything. The tree-god was in the tree, the corn-god in the corn, formed part of it, and so on with the mountain, the glen, the lake, the spring, stream, and sea. Therefore, when man cut down a tree, bruised and ate corn, slew the buffalo for food, he was sacrificing the gods and had to offer thanksgiving, apology, and amends. So the flesh that was fed by the bruised corn and the slaughtered ox-god had in its turn to be bruised and slashed, hence the necessity for the ceremonial victim or the scapegoat. Then, as religion was in a sense exclusive, understood by, and concerned more directly the god-king or priest-king and the regal-priestly caste, it was for them to intercede, to offer the personal sacrifice, and later to seek for the scapegoat. While at first the god-king was himself sacrificed on the altar to the end that the people as a whole should thrive, later we find the priest-king delegating that inconvenient honour. So the king lamenting his sins, and in the agony of his contrition, caused many of his chosen people to die under the sacerdotal lash or knife, and thus by vicarious floggings or spilling of blood made atonement for his shortcoming.

To this day the transition stage is strangely exemplified in Tibet, for at Lhassa a scapegoat is annually selected from among members of the lowest caste; he is known as the logon gyalpo, or "carrier of one year's ill-luck." This unhappy wretch is allowed a term of licence, during which he may go about the town doing practically as he pleases, but always carrying a yak's tail, which he waves over the heads of people to chase away evil from them and take their sins on his own head; then, amidst the ringing of bells, he is driven from the town with kicks and blows, after which he is allowed a certain time of grace, during which he may make good his escape; but he is generally so badly used that almost invariably he is overtaken and killed. What chiefly arrests our attention is the fact that the doomed man draws lots with one of the Grand Lhamas as to which of the two shall be the victim. Although, as far as man's memory runneth, there never was any doubt whatever as to the ultimate result, the formality of this mock lottery, a simulacrum of an appeal to a Power ruling the destinies of men, is pregnant with meaning, taking us back, indeed, to that exclusive form of worship of which we have written.

As one result of this exclusiveness we frequently find a strange diversity of interpretation of religious beliefs among the privileged classes and the masses. Thus we trace the most exalted spirituality among the ancient Egyptians side by side with seemingly grotesque materialistic religious observances. Among the black savages and the copper-coloured barbarians we have evidence of lofty ideals of a Supreme Creator and of a Heavenly Hereafter, understood but by the elect of the ruling and priestly castes, while to the people religion is often of the grossest character. We see this in its most degraded form as recorded by John Cartwright of the Kurds, who "do adore and worship the devil, to the end that he may not hurt them or their cattle," or, as Father Bouché writes of the West African, whose devotion to his fetish (the native oricha: "he who sees" or "listens to" prayers) is defended by the black man on the ground that the Beneficent Creator is very far off, but the demons too near at home, with power to do harm. Under such conditions the propitiatory sacrifice is the rule. Either the offended god has to be appeased, or more often the evil spirit put into a good temper by an offering. As the tree puts forth branches, the seed begets the waving corn and its grain crop, so to ensure prosperity--which in its essential meant multiplication, fertility--life, or its equivalent, had to be given up. Hence the hanging of victims to trees; the fettering of them to mountains to be pierced by the darts of the sun and the fire from the clouds and eaten by those aerial Mercuries, the vultures and eagles; the casting. of sacrifices into rivers that crop-fattening floods might follow, or into the sea to the end that fish might be plentiful and the elements kind; the spilling of human blood in temples; the anointing of living bodies or sticks or stones; and the mutilations and renunciations of various kinds and in differing degrees.

The Hindu carries this theory of penance so far that the mere repetition of prayers, ceremonial observances, accompanied by sacrifices, no matter by whom undertaken or for what purpose, gained an irresistible power for the persevering ascetic over heaven and earth, gods and demons. Not only holy men, but gods and, on the other hand, evil necromancers obtained such dominion by penance. Which unites them on the one side with the Egyptians and their theory in the efficacy of the sacred books as talismans and of the use of the mystic "Words of Power," on the other with the magicians and their "Abracadabra" and formularies. But, if we only go back far enough, we find that these "Words of Power" of any kind can only be secured by deeds of austerity, in the form either of personal penance or vicarious atonement, and propitiatory offerings of sacrifices. Herodotus says that the Egyptians beat themselves after offering sacrifices to Isis; but Strabo tells us of far more significant human sacrifice in the Caucasus, and darkly reveals two other forms at Phanagoria; for we know that both death and even more terrible kinds of self-sacrifice were offered to Astarte and to Baal. A point of which we are bound to take note is raised by Mr. J. G. Frazer, who suggests that Astarte became a moon goddess as the result of an error, or rather a confusion in art representation.

He points out that in the Semitic language the moon is masculine, and says that it is through the very early influence of Egyptian art in Assyria that the moon was associated with the Eastern goddess. Both Isis and Hathor are sun goddesses, usually depicted as adorned with the sun disc between two cows' horns placed on their heads. Often the horns are shown alone, and this may have given rise to the notion that the disc was the full moon and the horns the crescent moon. So, he holds, Astarte was given the horns of the crescent moon. While giving this all due weight, we must not forget that Astarte and her congeners were the consorts of Baal and his congeners, and regarded as the goddess of the night sky. The peculiar appearance of the moon in its last phase, with the darkened disc seemingly resting in the bright crescent cup; its total disappearance, to be followed by a reappearance of a small curved fillet which gradually grew, led to its being regarded as feminine, as abundant folklore testifies.

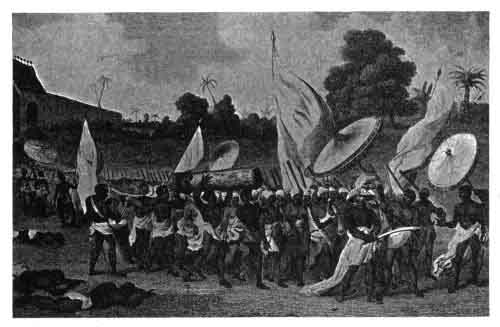

ARMED WOMEN, WITH THE KING AT THEIR HEAD, GOING TO WAR.

The Babylonian trinity consisted of Anu, the Creator; Sin, the sun god; and Ishtar, the moon goddess, who wore the crescent. As the planet was credited with influence on fertility generally, we have one reason for certain specialised sacrificial ceremonies connected with the worship of that goddess in her many manifestations, from the grim Ishtar to the more gentle, though often cruel, Venus. Some hint of this we have in relation to the Amazons of the Caucasus, who, according to Strabo, spent two months of each spring on a neighbouring mountain which formed the boundary between their own territory and that of the Gargarenses, who also ascended the mountain, so that, in obedience to ancient custom, they might perform common sacrifices. They met "in secret and in darkness," as might be expected from worshippers of Astarte. Evidence of other forms of self-sacrifice seem to be referred to in the legends of the American Amazons, e.g. (1) those who, in order to obtain the fertility talismans, had to wound their own bodies and offer their blood; (2) the whole Amazon tribe disappearing in a hole in the earth, led by an armadillo. Again, we have the tale of the infant placed in a bag and squeezed into a new and beautiful shape. As de Gubernatis has shown, the sack has two symbolical meanings: it is the night, or the clouds hiding the sun--therefore death; and it also denotes the act of devouring, another form of death. But night and death, though a conflict with the sun and light, are merely means to renewed life. The American Amazon sacrifices her boy so that he may have a beautiful rebirth, and, as we know, the saintly youth goes through a second form of sacrifice, being thrown into the lake and metamorphosed into a fish, that other symbol of life-giving power, and as such is worshipped by the women and finally again sacrificed. This sacrifice, it will be remembered, was effected by means of entanglement in a net woven from the hair of women. Now, in many places the worship of the moon goddess entailed abandonment of the female body within the dark temples to all strangers who might come, or in lieu thereof the milder offering of their tresses.

We are told in the Maha Bharata that Shantanu, descendant of Chandra, the great moon god of Northern India, married the incarnated Ganges. This beneficent river goddess had assumed human shape as a penance, probably in order to obtain greater power, and on her earthly pilgrimage she had met seven minor gods, who told her a most piteous tale. By an unlucky chance, these mystic seven had come between a holy hermit and his sacrifice, and he, being a man with enormous accumulated power as the result of long-continued acts of austerity, had, with the usual irascibility of the self-righteous, cursed them with the terrible doom: "Be born among men." So Ganges, taking pity on them, married Shantanu, and the seven sons of the royal and divine pair were the seven gods. As each was born, his earthly destiny having thus been fulfilled, she threw him into the mighty stream, whence he straightway entered heaven.

Here, it would seem, is a clear allusion to offers of human sacrifices to the fertilising goddess-river. It corresponds with what we know of the great Nile Sed ceremonials of the Egyptian flood time. Greatly modified, we find it again in the marriage of the Doge of Venice with the Adriatic, the Doge casting into the waves a symbolical ring that he might gain dominion over them; and yet again in the blessing of the waters, whether it be by priests in the Mediterranean or by czars on the Neva; or again by the offerings freely given by fishermen, which may take the form of the silver coin placed by Yorkshire boatmen in the corks of their nets, or the casting of the Adonis gardens into the waves by Sicilians and others. All these are sacrifices meant to repay the rivers (or the sea) for their gifts of food and prosperity to the people, sacrifices which in the case of the Ganges were afterwards softened into the custom of throwing the dead, or their ashes, into the sacred waters, so that they might be born again into a higher sphere, and in that of the Nile by the substitution of flowers for the maidens.

Herodotus has a curious story about the Libyan Auseans, who dwelt on the shores of Lake Titonis. Their maidens once a year held a feast in honour of Minerva. This we may take to be Neith or Nit,--that is, Night,--whom the Egyptians regarded as one of the trio of primitive gods, as the Mother, Nature, or in some sense the First Principle, and whom they depicted as a nude black female, arched over, resting on finger-tips and toes, bespangled with stars to represent the vault of heaven. At these celebrations it was the custom for the girls "to draw up in two bodies and to fight with staves and clubs." The loveliest maiden was clad in armour, of Greek design in the days of the chronicler, who wonders, but cannot guess, what manner of defensive gear they had worn before they came into contact with the Hellenes. Those of the girls who fell in the fight were declared to be "false maidens." Herodotus goes on to say that the Auseans held that Minerva (Neith) was the daughter of Neptune and Lake Titonis, and was adopted by Jupiter. The whole of this is suggestive of religious celebrations carrying out the idea of conflict between two elements or powers, good and evil, with the underlying notion of the benefits to be derived from sacrifice. The Ausean genesis of Neith is a tale of opposing influences, some life phenomena observed as the outcome of the blending of salt and fresh water under the action of the sun. It was appropriate enough that the ceremonies connected with the birth of the grim primitive Neith should be an affair of the armed guard of maidens and associated with strife between light and darkness, the triumph of the true devotees and the slaying of the false.

In another quarter Father Lamberti records that a tribe in the northern parts of the Caucasus, living in elevated fortified villages, did not bury their dead, but placed their bodies in hollow trees, and hung the deceased's clothing on the branches. Now, both the Asiatic Adonis and the Egyptian Osiris were originally tree gods, and their bodies were concealed in trees, so that it came about that human sacrifices were hung on trees. We find allusion to this custom in the Maha Bharata, where we are told that the Aswamedha horse led Rajah Arjuna to a land wherein men and women grew on trees, hanging therefrom, flourishing for a day and then dying. The same story occurs in connection with the women's island of El-Wak-Wak, the fruits crying out "Wak-wak" when they were ripe and then dying. Burton suggests that these trees were the calabash, "that grotesque growth, a vegetable elephant, whose gourds, something larger than a man's head, hang by a slender filament." This fruit of the calabash or baobab, the "monkey bread," contains an acid pulp which plays no insignificant part in the matter of provisioning; so here, as with the pine tree of Adonis and the palm of Osiris, and possibly the oak of the Caucasus, all food trees, we have an explanation of the arboreal hangings. It is at the base of the whole philosophy of the widespread worship of the Tree of Life--often the Tree of Death, death being the preliminary of renewed life.

Something of this necessity for sacrifice we find, too, in connection with the ancient religious observances of India, as we have been reminded by our notes on the Arddhanarishwara of the Caves of Elephanta. Both Shiva and Parvati are mountain-born and associated with human sacrifice--he actively, she passively. Shiva, "he of whom increase is," is the "Lord of the Mountains," whose seat is Mount Kailasa and whose haunts are the Himalayas, those grim ranges which the ancients regarded as the easternmost spur of the Caucasus, and which brought forth his consort, Parvati, "Daughter of the Mountains." He is a modified reincarnation of the hoary Vedic Rudra, "God of Storms," and although his emblems are the crescent moon of increase and the trident form of the fertilising thunderbolt, yet he also wears the deadly cobra and is decked with collars of snakes and human skulls.

Vestiges of human sacrifices are still extant in the seclusion of the Himalayas and other Indian mountain chains. For instance, among the Todas of the Nilgiris, where certain sacred herds migrate from one dairy to another, the Kaltmuk, or boy attendant, or acolyte, is fed with rich food when he reaches the new dairy (which corresponds to the term of licence accorded to the Tibetan logon gyalpo, and to other graces extended to scapegoats), and then, being led forth by the priest-dairyman, is heaped with curses, so that all ill-luck threatening the cattle, dairy, or priests may be transferred to his shoulders. This done, with many ceremonial formalities clarified butter is poured on the boy's head, and he is left alone. The priests return to the dairy: so does the boy, but at leisure, and he has to pass part of the night outside the hut, creeping in when all are asleep, and slipping out again before break of day. No one pays any attention to him until the morning's work is over, for he is not supposed to exist; then the priests go through a form of ritual for the removal of the curses from his head, and so the Kaltmuk is free to return to his duties.

But there can be little doubt that this second ceremonial is an innovation; originally the boy did not return after the sundown anointing. In other cases, it is over certain stones away from the dairies that either butter-milk or clarified butter is poured, and we may conjecture that these were altars for human sacrifices, as the anointing is never observed when calves or bullocks are sacrificed either for purposes of augury or as offerings to the ghosts of the departed. Ghee was commonly poured over sacrificial victims, and ancient Indian religious books tell us that the vampire snake-worshipping women and other magicians of the forests anointed their own bodies with the fat of victims when they began their incantations. The same thing, we have seen, occurred in the Congo, in connection with Voodooism, and probably occurred in the Andes. As for Shiva, while he wields that life symbol the trident, and that other the cobra, he also grasps the pasha, or sacrificial noose, with which victims were strangled, and of which certain sects made such ghastly use, approximating to the practices of the Amur Tatars and the women royal guards of the White Nile.

Of the Amazons' part in such practices as these we have much other evidence. As we have already remarked, in early stages of civilisation the king is usually a god-king, and later a priest-king. It was a high office, but, as we have seen, one often fraught with awful consequences; for the divine ruler passed to the other world self-immolated, or by the assistance of his priestly attendants, who often were women. Thus we see the Behr king on the White Nile surrounded by a female guard, strangled when on his death-bed. This form of "happy dispatch" for honoured persons was widely prevalent. It still survives in a degraded form among the "Fish-Skinned" Tatars of the Amur. These degenerate nomads, who live on fish and dress in fish skins, habitually strangle their old folk with certain suggestive ritual. Drums are beaten, and all persons leave the camp except the victim and two near relatives, who act as executioners, or rather sacrificers. The grim work is carried out in the tent while the drums are being beaten outside. That women guards took part in such ceremonial death-scenes has been shown, and their semi-sacerdotal office is evident in many ways. Snelgrave reports that in his day the King of Dahomey, though not secluded, yet kept aloof from his people and even his courtiers. His chiefs and others during audiences, having prostrated themselves and kissed the ground, whispered whatever they wished to reach the royal cars into those of an old woman, who went to the king, transmitted the message, and then returned with the answer. Which shows another stage in the intervention of the privileged councillor between the sacred person and the supplicant. Then, as we know, the petty King of Abeokuta, also on the west coast of Africa, was guarded by women, while in the same region the King of Yoruba formerly possessed a female guard, and the executioner "wives" of the King of Wydah were 5000 in number.

Turning in another direction, we find the same thing presenting itself at Pataliputra in the Punjab, and we hear of Indian rajahs going out hunting surrounded by armed female warriors, corresponding in this particular with the King of Dahomey and his picked Elephant Huntresses. In Bantam it appears to have been the custom for the women royal guards to elect from among their own sons a new king in default of a direct heir. All this we may compare to Megasthenes' account, who says that the women guards at Pataliputra were at liberty to kill the king if found drunk, the executioner marrying the successor.

Throughout all this we may note differences of detail, but the mission of these women as a buffer class between the claimant to superhuman attributes and his people is clear enough. How illuminating, therefore, to find this phenomenon of organising a special guard of women repeating itself in Eastern China in the fifth and sixth decades of the nineteenth century, as though spontaneously evolved from the exigencies of the case. When those misnamed "Princes of Peace," the Tae-pings, inaugurated a vast religious movement, they declared that they were expecting a sacred leader. To them appeared that "Celestial Virtue," Tien-wang, and, claiming both divinity in his own person as second son of God and dominion over the world as regent of the Celestial King, it seemed to follow naturally that he should be protected by a bodyguard of women warriors. And although the religious movement quickly assumed a political phase, the fanatical aspect only increased as the Celestial King and his female guard swept through the land, carrying fire and sword in every direction in the name of peace and goodwill.

It is remarkable that the ancients in writing of the African Amazons, and American Indian traditions, describe the warrior women as a "white" race. It has been argued from this that both the African and American Amazons must have been emigrants from Europe or Asia. But assuming that there was foundation for the reports, the fact would be capable of quite another interpretation. It would point, indeed, to an exclusive class. As Sir Richard Burton rightly says, though in a different connection: "Rank makes some difference in colour; the higher it is the fairer the skin. . . . Even amongst the negroes of Central Africa we find the chief lighter-tinted than his subjects." To the black or copper-coloured a slight lessening in shade means "white." Tradition, therefore, seems to indicate, at all events in the earlier stages, the existence of an exclusive caste of warrior women both in Africa and America, and with some associated idea of self-sacrifice. They were, like the Lenâpé "Woman" tribe of North America, and the mutilated beings of Central and South Africa, as well as of Asia Minor in ancient times, somewhat in the position of scapegoats.

Captain John Adams, writing about the Congo (in 1823), says: "One of the conditions by which a female is admitted into the order of priesthood is leading a life of celibacy and renouncing the pleasures of the world." This renunciation was certainly the prevalent idea as regards the Dahomeyan Amazons in the early days, and perhaps also, so far as regards the queen, in the regions of the White Nile. At least one of the Portuguese missionaries declares that the queen of the Abyssinian Amazons was looked up to by her neighbours as a goddess, and the same was said of the mysterious foundress of that equally mysterious second great will-o'-the-wisp golden city of the continent, Dobayba, about which Vasca Nuñez de Balboa and his successors on the Isthmus of Darien heard so much and dared many perils in vain to seek. Certain legends said that Dobayba was a mighty female who lived at the beginning of time, mother of the god who created the sun, moon, and all things--in fact, the supreme Nature goddess. Others asserted that she was a powerful Indian princess who had held sway among the mountains, built a beautiful city, enriched with gold, and gained widespread renown for her wisdom and military prowess. After her death she was regarded as a divinity and worshipped in a golden temple. Traditions were persistent of a rich concealed temple, where neighbouring caciques and their subjects made pilgrimage, carrying offerings of gold and slaves to be sacrificed. Neglect of these rites brought drought, most dreaded of Nature's punishments. Farther south we hear much the same tale of the Brazilian warrior women (who were "whiter than other women") in Nuño de Gusman's letter to the Emperor Charles V.

Nevertheless, the vestal state is by no means essential to the religious idea. Angelo Mosso, writing of the Minoan age in Crete, finely says: "Priestesses were mothers and maidens who initiated the Greek race into the religion of beauty." That, however, was in an advanced stage. Often the sacerdotal state might, indeed, enjoin abstention from marriage, yet demand personal sacrifice. This was unquestionably the case with the followers of Astarte. There appears to be a hint of that state of affairs in the curious traditions recorded by Strabo which we have already cited, and again in the legend of the American Amazons, who took to the hill caves with only one old man, to whom they ministered. The "marriage" to the King of Dahomey, and at Wydah, would have a ceremonial import if we regard these monarchs as priest-(descendants of tribal god-) kings. And in this connection we may take note of Sir Richard Burton's description of the eighteen Tansi-no, or fetish women, of Dahomey, who had charge of the king's grave. These women, who were accompanied by a band playing on horns and rattles (always and everywhere associated with magic and incantations), were called the "King's Ghosts," and were said to be of the blood royal. These were the terrestrial counterparts of the sacrificed female retinue who accompanied the dead king into the grave. The mere fact that the Dahomeyan dynasty was a modern one does not invalidate such arguments, for the kings and the people were inheritors of the immemorial customs. Another interesting point is that these black Amazons, when they took their walks abroad, were always preceded by a small girl ringing a bell, so that common mortals should make way for the privileged women, reminding us irresistibly of the vestal processions in classic times. Nor must we forget that tradition said the Amazons from the Thermodon dwelt within the sanctuary at Ephesus. Pausanias makes distinct mention of this, though he contradicts the story that the sanctuary had actually been founded by them. Putting aside all question of Themysciran Amazons, it would seem from this statement quite clear that some of the priestesses and female attendants must have had a reputation for more or less martial qualities: they were at once the ministrants and the guards. That Artemis herself still retained her Eastern reputation as a warrior appears not improbable when we consider that at Aulis in Attica there were two statues to her, one in the guise of a huntress, while in the other she was represented as grasping two torches, which symbolised not the holding aloft of the pure flame of the nobler passions (generally represented by a single torch), but the brandishing of war signals.

Two matters may be touched upon lightly: the association of the Amazons with sun and moon worship and with cannibalism. Strabo is our authority for the sanctuary to the moon god in the Caucasus and the shrine to Venus Apatura, while we know the Greeks all declared the Amazons worshipped Artemis (Astarte) and carried crescent-shaped shields. In Africa such records as we have connect the women warriors with the sun god, as evidenced by their use of snake skins, alligator and tortoise emblems, and their alliance with Horus; but Ptolemy refers to the Moon Mountain in Central Africa, apparently in the regions where the Abyssinian and White Nile Amazons were placed. In America we find the association with moon-worship both through the legends and the greenstone fertility amulets. In the mountains of the upper reaches of the Amazon River, however, we find great peaks crowned by temples bearing symbols both of the sun and moon, and other mountains called the Mansion of the Sun, the Seat of the Sun, and so on.

The connection with cannibalism is rather more vague except in so far as it concerns the Far East. Certain Greek writers say that the Amazons of the Thermodon drank out of human skulls, and many of the Asiatic legends refer to the dwellers in female colonies as eaters of men. But this expression of "eaters of men" may generally be taken as a figure of speech, on the one hand paying a doubtful tribute to women's wiles, and on the other referring picturesquely to their fighting powers. An army that carries all before it "eats up" the enemy, just like a cloud of locusts. In this sense, to "eat up" men is to slay, to wipe out, although it must be allowed that the figurative may originally have been truly descriptive. This is undoubtedly the case so far as Africa is concerned. The usual Greek qualifying epithet applied to the women was the milder "slayer of men." The Eastern legends--those related of Ceylon, of the great Indian forests, and of the imaginary El-Wak-Wak--clearly allude to anthropophagy as a habitual practice of the women. We have trace of this in at least one of the American tales, where we are told of a mother placing her sick boy in a bag and crushing him into a beautiful shape, which is suggestive of something more than ordinary human sacrifice, for placing in a bag is often a synonym for "devouring." Cannibalism existed in all this part of the continent, nay, still persists there, while one tribe possesses the remarkable habit and secret of removing bones from corpses and then dwarfing and desiccating them. There are traditions, too, in the Andes of human sacrifices for the purpose of ceremonial anointings, a practice which must have been in force prior to the days of the Incas, for we are told that this mysterious race was opposed to all such customs. It must be remembered that cannibalism had a religious import, though it may have originated in various parts of the world from motives of economic pressure. It was not, however, always a matter of satisfying appetite, the cravings of a depraved habit, or even an exhibition of revenge; there was the idea that by eating the enemy his strength was incorporated, and even the dead man's ghost enlisted as a kind of secondary guardian spirit. For the same reason the skulls of enemies were kept, and placed high on poles, above huts, and so on, as Herodotus reports of the savage Tauri, and even fed, as by the "Head-Hunters" of Borneo, who stuck cheroots between the parched lips to keep these ghastly guardians in good humour.

As a rule, however, the armed Amazons seemed to be ranged against cannibalism. In Greek tradition the Amazons not only fought and overcame the man-eating gryphons, but, according to some, helped Hercules in his struggles with the Hydra, and farther back assisted Dionysus against the giants. As to the early African Amazons, we also see them waging war against the savage black races, who, on the testimony of even late Arabic authors, we know, "ate men"; and this warfare was carried on, Pigafetta tells us, by the Congo Amazons and the giant anthropophagists down to the end of the sixteenth century.

It is curious to find that where rumours of fighting Amazons are most persistent we have abundant proof of primitive savagery lingering on. The fabulous Isle of the East, inhabited by women, where human sacrifices prevailed, was called El-Wak-Wak because "Wak-wak" was the only word uttered by the ceremonial victims. The Western African women, in their endeavours to reach Egypt, had to pass through a land peopled by cannibal tribes bearing the repeat names Nem-Nems, Gnem-Gnems, the Niam-Niams of to-day, who call their neighbours the Akka Tikki-Tikki.1 In the Amazon valley and the Andes such duplication is common as regards topographical names--for instance, the Huar-huari and Pina-pina rivers, Lake Titikaka; the mountain Sara-sara; Chapi-chapi village; and there is also the Inje-inje tribe, who are extremely retiring forest folk, still in the stone age of development, and are supposed to use only the one word "inje" doubled, with different inflexions to express all their wants and feelings, in this resembling the tree-grown puellæ Wakwakiensis. This repetition in all kinds of ways is a favourite form of emphasis with primitive people, just as it is with small children.

In passing, we may note the fact that in the three great centres of Amazonian traditions--in Asia, Africa, and America--though we have mention of mountains and forests, the real seats of activity are on extensive alluvial plains. Such situations have always been cradles of new nations and of social revolutions, for it is in these rich granaries that peoples mingle, man multiplies, where interests clash, giving rise to upheavals and abnormalities, until a new order of affairs has been evolved.

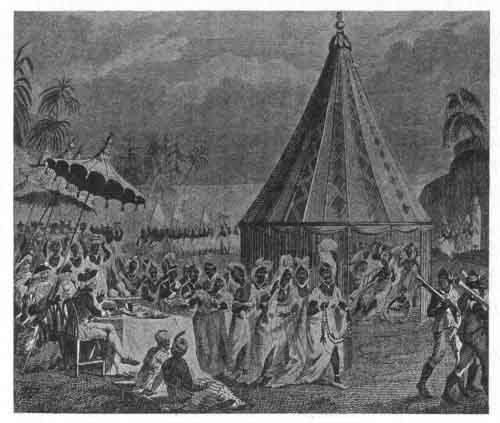

PUBLIC PROCESSION OF THE KING'S WOMEN, ETC.

That there was some justification for the legends there can be no reasonable doubt. The very diversity met with in regard to them is strongly in favour of some solid foundation having existed; because, if we consider them critically, they answer to some need of humanity. If we take into account the tendency, on the one hand, to exaggerate, and on the other the frailty of mankind in the matter of giving and receiving evidence, we have much still left. We know that the Greeks loved the declamatory form; the Orientals revel in the superlative. We have seen the pitfalls that beset the inquiring explorers in America, and we have a similar note of warning from West Africa, where Father Bouché says: "Native interpreters aim less at being very accurate than at not displeasing the white man. They do not fail to flatter him by giving translations which they know he desires, or rather which they are aware will fall in with his views."

Even apart from what we may be permitted to call these amenities of the "traitrous translators'" art mistakes may arise innocently enough from sheer confusion of tongues, a blundering all too easy in matters both great and small, as daily experience sufficiently demonstrates. Take as an instance a little incident that came under the writer's own observation. A very small boy was in the habit of calling a particularly favoured lady of his acquaintance his "clean friend," to her immense delight but to the scandalised bewilderment of the child's parents. Then it was discovered that the youngster had been translating Italian into English through the medium of French. "Propria" became "propre," and, of course, "propre" meant "clean," therefore "il mia propria amica" ("mine own particular friend") became his "clean friend." Assuredly perfectly logical, and not without a certain poetical symbolism of speech all the more pleasing for its very spontaneous unconscious cerebration, yet which, under different circumstances, might have proved grotesquely misleading. We are all--savages, barbarians, and civilised--little children in this transmutation of thought into concrete phrase, with the help of all too unstable words and the evasive flux of grammatical rules. Yet admitting all this, and allowing it to have due weight in its application to our particular study, we may conclude that the legends should be credited to a large extent.

Let us clearly bear in mind our original three divisions of the subject. Of the third we need say little, for the matriarchal stage of civilisation has to be accepted in many quarters; and of great and little nations governed by women who not seldom were great fighters before the Lord, history repeatedly attests. We will only allude to this as a possible source of confusion, the outstanding deeds of a queen and her women captains being tacked on to or mixed up with the traditions of some more or less transitory women's camp. Into this category the Damute Amazons evidently, and the Bohemian Valasca probably, fall.

We have, then, the two first divisions. That, through the exigencies of social organisation, women and young children had, and still have in a minor degree, to live alone periodically and for many months on end, is proved by actual experience. Local conditions may have occasionally emphasised this peculiarity, which would easily be evolved into a theory of an autonomous female community. It may be conceded that these conditions, combined with a rebellion against male tyranny under the stress of struggling from savagedom to higher things, may frequently have led to revolts and temporary pacts among women, who lived apart and only admitted men as an act of toleration or policy. Such "nations" and "tribes" were probably enough also brought about as the result of conquest, the conquerors having slain all males, and, for a time, which would vary according to local social progress and especially topographical peculiarities, failed to subdue the females. Where there were mountains difficult of access, or dense forests, probably with swamp-isolated islands, no doubt the women with their children would preserve their savage aloofness all the longer, and would, having almost certainly a previous acquaintance with warfare, be able to give a very good account. of themselves as warriors, whether acting purely on the defensive or actively retaliating on the enemy. Under these circumstances, communication between the sexes would arise only gradually, and be of a spasmodic, even of a clandestine nature, until the inevitable day came when the women surrendered to the men on the latter's own terms; for such is the predestined fate of all such "commonwealths," ancient or modern. But, given a mountainous country, or a district covered by primeval forest, and obstinate resistance, the women tribe would soon be regarded as something outside of nature, either to be cursed or fought, and almost certainly to be looked upon with a mixture of dread and veneration.

This brings us to the fighting organisation. Now, both the temporary colonies of women evolved by natural everyday causes, and those feminine camps brought about by an abnormal concatenation of circumstances, would obviously have to organise for defence in savage and barbaric stages of evolution; and where the women had been accustomed to aid and abet their men in warfare, which is generally the case among nomadic tribes and mountaineers or forest dwellers, this organisation might be carried very far indeed. There were, then, we may conclude, women banded together to defend their homes, and others who joined the ranks, or even led men in warfare. But the fighting organisations as such were not the outcome of unisex "nations," they belong to the domain of religion. The god-king would have his armed guard, and these, we have seen, were often armed women, either because of the form of the worship or because of their fierceness, and such guards were, at all events in the earlier periods, a sacrificial body; and then the priest-king would strengthen his guards, converting them from his jailers, or perhaps more correctly from those who assisted him in his personal self-immolation, into ministrants of his own personal cult and policy, as exemplified by the King of Wydah and his thousands of "wives" who executed the royal sentences. When such guards grew numerous, it must often have become a matter of convenience and expediency to assign them special quarters, or even provinces, thus forming the nations, as we are told was the case in the Congo, and seems probable in connection with some of the sanctuaries in the Caucasus and Asia Minor. In such cases the women warriors would naturally come in time to form castes--or perhaps we had better say a privileged circle within the nation--and not a "nation" by themselves. They formed part of the social economy, and were not outside of it, though they might appear to be so when coming into contact with other races. And so we shall conclude by rejecting the idea of a long-sustained women's state, or even tribe (allowing for the exception of a transitory accident), while accepting the "women's islands" in a modified form, and the fighting Amazons as religious, or regal-religious, bodies.

Even thus stripped of much of the marvellous, the problem is intensely interesting. While teaching us the fundamental unity of nature, manifested not less in the tendency to fall into error and distort half-truths until they degenerate so far as to seemingly sanction ghastly practices, than in its aspirations to higher things, it happily points to the immense strides accomplished in the march of progress. Onrushing waves necessarily involve the disconcerting phenomena of reflux eddies, which seem to tell of the elusive nature of hope, so that we are often cast down as we reflect on present conditions and contrast them with the near past, mellowed as such views are into a haunting beauty by the glamour of blurring sentiment. Nevertheless, if our retrospective glance is sufficiently comprehensive, the evidence of secured progress is unmistakable, and so we are heartened to look forward to a bright future that assuredly will not be ours, but to which humanity is heir, and whose advent we may all in some measure contribute to hasten.

Footnotes

208:1 According to Arab traditions, Gian ben Gian was the gigantic king of the jinns, founder of the pyramids, who, having rebelled against God, was defeated by Lucifer before his fall. The jinns then became mischievous spirits of the dark and of lonely places.