Celtic Myth and Legend Poetry and Romance

by Charles Squire

CHAPTER XXI

THE MYTHOLOGICAL "COMING OF ARTHUR"

The "Coming of Arthur", his sudden rise into prominence, is one of the many problems of the Celtic mythology. He is not mentioned in any of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi, which deal with the races of British gods equivalent to the Gaelic Tuatha Dé Danann. The earliest references to him in Welsh literature seem to treat him as merely a warrior-chieftain, no better, if no worse, than several others, such as "Geraint, a tributary prince of Devon", immortalized both by the bards1 and by Tennyson. Then, following upon this, we find him lifted to the extraordinary position of a king of gods, to whom the old divine families of Dôn, of Llyr, and of Pwyll pay unquestioned homage. Triads tell us that Lludd--the Zeus of the older Pantheon--was one of Arthur's "Three Chief War-Knights", and Arawn, King of Hades, one of his "Three Chief Counselling Knights". In the story called the "Dream of Rhonabwy", in the Red Book of Hergest, he is shown as a leader to whom are subject those we know to have been of divine race--sons of Nudd, of Llyr, of Brân, of Govannan, and of Arianrod. In another "Red Book" tale, that of "Kulhwch and Olwen", even greater gods are his vassals. Amaethon son of Dôn, ploughs for him, and Govannan son of Dôn, rids the iron, while two other sons of Beli, Nynniaw and Peibaw, "turned into oxen on account of their sins", toil at the yoke, that a mountain may be cleared and tilled and the harvest reaped in one day. He assembles his champions to seek the "treasures of Britain"; and Manawyddan son of Llyr, Gwyn son of Nudd, and Pryderi son of Pwyll rally round him at his call.

The most probable, and only adequate explanation, is given by Professor Rhys, who considers that the fames of two separate Arthurs have been accidentally confused, to the exceeding renown of a composite, half-real, half-mythical personage into whom the two blended.1 One of these was a divine Arthur, a god more or less widely worshipped in the Celtic world--the same, no doubt, whom an ex voto inscription found in south-eastern France calls Mercurius Artaius.2 The other was a human Arthur, who held among the Britons the post which, under Roman domination, had been called Comes Britanniæ. This "Count of Britain" was the supreme military authority; he had a roving commission to defend the country against foreign invasion; and under his orders were two slightly subordinate officers, the Dux Britanniarum (Duke of the Britains), who had charge of the northern wall, and the Comes Littoris Saxonici (Count of the Saxon Shore), who guarded the south-eastern coasts. The Britons, after the departure of the Romans, long kept intact the organization their conquerors had built up; and it seems reasonable to believe that this post of leader in war was the same which early Welsh literature describes as that of "emperor", a title given to Arthur alone among the British heroes.1 The fame of Arthur the Emperor blended with that of Arthur the God, so that it became conterminous with the area over which we have traced Brythonic settlement in Great Britain.2 Hence the many disputes, ably, if unprofitably, conducted, over "Arthurian localities" and the sites of such cities as Camelot, and of Arthur's twelve great battles. Historical elements doubtless coloured the tales of Arthur and his companions, but they are none the less as essentially mythic as those told of their Gaelic analogues--the Red Branch Heroes of Ulster and the Fenians.

Of those two cycles, it is with the latter that the Arthurian legend shows most affinity.3 Arthur's position as supreme war-leader of Britain curiously parallels that of Finn's as general of a "native Irish militia". His "Round Table" of warriors also reminds one of Finn's Fenians sworn to adventure. Both alike battle with human and superhuman foes.

Both alike harry Europe, even to the walls of Rome. The love-story of Arthur, his wife Gwynhwyvar (Guinevere), and his nephew Medrawt (Mordred), resembles in several ways that of Finn, his wife Grainne, and his nephew Diarmait. In the stories of the last battles of Arthur and of the Fenians, the essence of the kindred myth still subsists, though the actual exponents of it slightly differ. At the fight of Camlan, it was Arthur and Medrawt themselves who fought the final duel. But in the last stand of the Fenians at Gabhra, the original protagonists have given place to their descendants and representatives. Both Finn and Cormac were already dead. It is Oscar, Finn's grandson, and Cairbré, Cormac's son, who fight and slay each other. And again, just as Arthur was thought by many not to have really died, but to have passed to "the island valley of Avilion", so a Scottish legend tells us how, ages after the Fenians, a man, landing by chance upon a mysterious western island, met and spoke with Finn mac Coul. Even the alternative legend, which makes Arthur and his warriors wait under the earth in a magic sleep for the return of their triumph, is also told of the Fenians.

But these parallels, though they illustrate Arthur's pre-eminence, do not show his real place among the gods. To determine this, we must examine the ranks of the older dynasties carefully, to see if any are missing whose attributes this new-corner may have inherited. We find Lludd and Gwyn, Arawn, Pryderi, and Manawyddan side by side with him under their own names. Among the children of Dôn are Amaethon and Govannan. But here the list stops, with a notable omission. There is no mention, in later myth, of Gwydion. That greatest of the sons of Dôn has fallen out, and vanished without a sign.

Singularly enough, too, the same stories that were once told of Gwydion are now attached to the name of Arthur. So that we may assume, with Professor Rhys, that Arthur, the prominent god of a new Pantheon, has taken the place of Gwydion in the old.1 A comparison of Gwydion-myths and Arthur-myths shows an almost exact correspondence in everything but name.

Like Gwydion, Arthur is the exponent of culture and of arts. Therefore we see him carrying on the same war against the underworld for wealth and wisdom that Gwydion and the sons of Dôn waged against the sons of Llyr, the Sea, and of Pwyll, the Head of Hades.

Like Gwydion, too, Arthur suffered early reverses. He failed, indeed, even where his prototype had succeeded. Gwydion, we know from the Mabinogi of Mâth, successfully stole Pryderi's pigs, but Arthur was utterly baffled in his attempt to capture the swine of a similar prince of the underworld, called March son of Meirchion.2 Also as with Gwydion, his earliest reconnaissance of Hades was disastrous, and led to his capture and imprisonment. Manawyddan son of Llyr, confined him in the mysterious and gruesome bone-fortress of Oeth and Anoeth, and there he languished for three days and three nights before a rescuer came in the person of Goreu, his cousin.1 But, in the end, he triumphed. A Welsh poem, ascribed to the bard Taliesin, relates, under the title "The Spoiling of Annwn",2 an expedition of Arthur and his followers into the very heart of that country, from which he appears to have returned (for the verses are somewhat obscure) with the loss of almost all his men, but in possession of the object of his quest--the magic cauldron of inspiration and poetry.

Taliesin tells the story as an eye-witness. He may well have done so; for it was his boast that from the creation of the world he had allowed himself to miss no event of importance. He was in Heaven, he tells us,3 when Lucifer fell, and in the Court of Dôn before Gwydion was born; he had been among the constellations both with Mary Magdalene and with the pagan goddess Arianrod; he carried a banner before Alexander, and was chief director of the building of the Tower of Babel; he saw the fall of Troy and the founding of Rome; he was with Noah in the Ark, and he witnessed the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah; and he was present both at the Manger of Bethlehem and at the Cross of Calvary. But, unfortunately, Taliesin, as a credible personage, rests under exactly the same disabilities as Arthur himself. It is not denied by scholars that there was a real Taliesin, a sixth-century bard to whom were attributed, and who may have actually composed, some of the poems in the Book of Taliesin.1 But there was also another Taliesin, whom mythical poet of the British Celts, Professor Rhys is inclined to equate with the Gaelic Ossian.2 The traditions of the two mingled, endowing the historic Taliesin with the god-like attributes of his predecessor, and clothing the mythical Taliesin with some of the actuality of his successor.3

It is regrettable that our bard did not at times sing a little less incoherently, for his poem contains the fullest description that has come down to us of the other world as the Britons conceived it. Apparently the numerous names, all different and some now untranslatable, refer to the same place, and they must be collated to form a right idea of what Annwn was like. With the exception of an obviously spurious last verse, here omitted, the poem is magnificently pagan, and quite a storehouse of British mythology4.

"I will praise the Sovereign, supreme Lord of the land,

Who hath extended his dominion over the shore of the world.

Stout was the prison of Gweir1, in Caer Sidi,

Through the spite of Pwyll and Pryderi:

No one before him went into it.

The heavy blue chain firmly held the youth,

And before the spoils of Annwn woefully he sang,

And thenceforth till doom he shall remain a bard.

Thrice enough to fill Prydwen2 we went into it;

Except seven, none returned from Caer Sidi3.

"Am I not a candidate for fame, to be heard in song

In Caer Pedryvan4, four times revolving?

The first word from the cauldron, when was it spoken?

By the breath of nine maidens it was gently warmed.

Is it not the cauldron of the chief of Annwn? What is its

fashion?

A rim of pearls is round its edge.

It will not cook the food of a coward or one forsworn.

A sword flashing bright will be raised to him,

And left in the hand of Lleminawg.

And before the door of the gate of Uffern5 the lamp was burning.

When we went with Arthur--a splendid labour!--

Except seven, none returned from Caer Vedwyd6.

"Am I not a candidate for fame, to be heard in song

In Caer Pedryvan, in the Isle of the Strong Door,

Where twilight and pitchy darkness meet together,

And bright wine is the drink of the host?

Thrice enough to fill Prydwen we went on the sea.

Except seven, none returned from Caer Rigor7.

"I will not allow much praise to the leaders of

literature.

Beyond Caer Wydyr1 they saw not the prowess of Arthur;

Three-score hundreds stood on the walls;

It was hard to converse with their watchman.

Thrice enough to fill Prydwen we went with Arthur;

Except seven, none returned from Caer Golud2.

"I will not allow much praise to the spiritless.

They know not on what day, or who caused it,

Or in what hour of the serene day Cwy was born,

Or who caused that he should not go to the dales of Devwy.

They know not the brindled ox with the broad head-band,

Whose yoke is seven-score handbreadths.

When we went with Arthur, of mournful memory,

Except seven, none returned from Caer Vandwy3.

"I will not allow much praise to those of drooping

courage,

They know not on what day the chief arose,

Nor in what hour of the serene day the owner was born,

Nor what animal they keep, with its head of silver.

When we went with Arthur, of anxious striving,

Except seven, none returned from Caer Ochren4".

Many of the allusions of this poem will perhaps never be explained. We know no better than the "leaders of literature" whom the vainglorious Taliesin taunted with their ignorance and lack of spirit in what hour Cwy was born, or even who he was, much less who prevented him from going to the dales of Devwy, wherever they may have been.

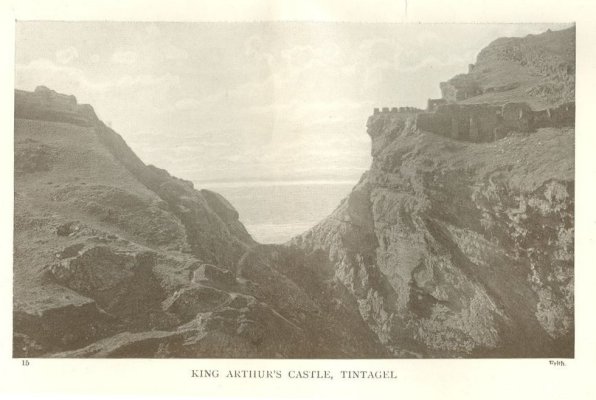

KING ARTHUR'S CASTLE, TINTAGEL

We are in the dark as much as they were with regard to the significance of the brindled ox with the broad head-band, and of the other animal with the silver head.1 But the, earlier portion of the poem is, fortunately, clearer, and it gives glimpses of a grandeur of savage imagination. The strong-doored, foursquare fortress of glass, manned by its dumb, ghostly sentinels, spun round in never-ceasing revolution, so that few could find its entrance; it was pitch-dark save for the twilight made by the lamp burning before its circling gate; feasting went on there, and revelry, and in its centre, choicest of its many riches, was the pearl-rimmed cauldron of poetry and inspiration, kept bubbling by the breaths of nine British pythonesses, so that it might give forth its oracles. To this scanty information we may add a few lines, also by Taliesin, and contained in a poem called "A Song Concerning the Sons of Llyr ab Brochwel Powys":--

"Perfect is my chair in Caer Sidi:

Plague and age hurt not him who 's in it--

They know, Manawyddan and Pryderi.

Three organs round a fire sing before it,

And about its points are ocean's streams

And the abundant well above it--,

Sweeter than white wine the drink in it."2

Little is, however, added by it to our knowledge. It reminds us that Annwn was surrounded by the sea--"the heavy blue chain" which held Gweir so firmly;--it informs us that the "bright wine" which was "the drink of the host" was kept in a well; it adds to the revelry the singing of the three organs; it makes a point that its inhabitants were freed from age and death; and, last of all, it shows us, as we might have expected, the ubiquitous Taliesin as a privileged resident of this delightful region. We have two clues as to where the country may have been situated. Lundy Island, off the coast of Devonshire, was anciently called Ynys Wair, the "Island of Gweir", or Gwydion. The Welsh translation of the Seint Greal, an Anglo-Norman romance embodying much of the old mythology, locates its "Turning Castle"--evidently the same as Caer Sidi--in the district around and comprising Puffin Island off the coast of Anglesey.1 But these are slender threads by which to tether to firm ground a realm of the imagination.

With Gwydion, too, have disappeared the whole of the characters connected with him in that portion of the Mabinogi of Mâth, Son of Mathonwy, which recounts the myth of the birth of the sun-god. Neither Mâth himself, nor Lieu Llaw Gyffes, nor Dylan, nor their mother, Arianrod, play any more part; they have vanished as completely as Gwydion. But the essence of the myth of which they were the figures remains intact. Gwydion was the father by his sister Arianrod, wife of a waning heaven-god called Nwyvre (Space), of twin sons, Lieu, a god of light, and Dylan, a god of darkness; and we find this same story woven into the very innermost texture of the legend of Arthur.2 The new Arianrod, though called "Morgawse" by Sir Thomas Malory1, and "Anna" by Geoffrey of Monmouth2, is known to earlier Welsh myth as "Gwyar"3. She was the sister of Arthur and the wife of the sky-god, Lludd, and her name, which means "shed blood" or "gore", reminds us of the relationship of the Morrígú, the war-goddess of the Gaels, to the heaven-god Nuada4. The new Lleu Llaw Gyffes is called Gwalchmei, that is, the "Falcon of May"5, and the new Dylan is Medrawt, at once Arthur's son and Gwalchmei's brother, and the bitterest enemy of both6.

Besides these "old friends with new faces", Arthur brings with him into prominence a fresh Pantheon, most of whom also replace the older gods of the heavens and earth and the regions under the earth. The Zeus of Arthur's cycle is called Myrddin, who passed into the Norman-French romances as "Merlin". All the myths told of him bear witness to his high estate. The first name of Britain, before it was inhabited, was, we learn from a triad, Clas Myrddin, that is, "Myrddin's Enclosure".7 He is given a wife whose attributes recall those of the consorts of Nuada and Lludd. She is described as the only daughter of Coel--the British name of the Gaulish Camulus, a god of war and the sky--and was called Elen Lwyddawg, that is, "Elen, Leader of Hosts". Her memory is still preserved in Wales in connection with ancient roadways; such names as Ffordd Elen ("Elen's Road") and Sarn Elen ("Elen's Causeway") seem to show that the paths on which armies marched were ascribed or dedicated to her.1 As Myrddin's wife, she is credited with having founded the town of Carmarthen (Caer Myrddin), as well as the "highest fortress in Arvon", which must have been the site near Beddgelert still called Dinas Emrys, the "Town of Emrys", one of Myrddin's epithets or names.2

Professor Rhys is inclined to credit Myrddin, or, rather, the British Zeus under whatever name, with having been the god especially worshipped at Stonehenge.3 Certainly this impressive temple, ever unroofed and open to the sun and wind and rain of heaven, would seem peculiarly appropriate to a British supreme god of light and sky. Neither are we quite without documentary evidence which will allow us to connect it with him. Geoffrey of Monmouth4, whose historical fictions usually conceal mythological facts, relates that the stones which compose it were erected by Merlin. Before that, they had stood in Ireland, upon a hill which Geoffrey calls "Mount Killaraus", and which can be identified as the same spot known to Irish legend as the "Hill of Uisnech", and, still earlier, connected with Balor. According to British tradition, the primeval giants who first colonized Ireland had brought them from their original home on "the farthest coast of Africa", on account of their miraculous virtues; for any water in which they were bathed became a sovereign remedy either for sickness or for wounds. By the order of Aurelius, a half-real, half-mythical king of Britain, Merlin brought them thence to England, to be set up on Salisbury Plain as a monument to the British chieftains treacherously slain by Hengist and his Saxons. With this scrap of native information about Stonehenge we may compare the only other piece we have--the account of the classic Diodorus, who called it a temple of Apollo.1 At first, these two statements seem to conflict. But it is far from unlikely that the earlier Celtic settlers in Britain made little or no religious distinction between sky and sun. The sun-god, as a separate personage, seems to have been the conception of a comparatively late age. Celtic mythology allows us to be present, as it were, at the births both of the Gaelic Lugh Lamhfada and the British Lleu Llaw Gyffes.

Even the well-known story of Myrddin's, or Merlin's final imprisonment in a tomb of airy enchantment--"a tour withouten walles, or withoute eny closure"--reads marvellously like a myth of the sun "with all his fires and travelling glories round him".2 Encircled, shielded, and made splendid by his atmosphere of living light, the Lord of Heaven moves slowly towards the west, to disappear at last into the sea (as one local version of the myth puts it), or on to a far-off island (as another says), or into a dark forest (the choice of a third).3 When the myth became finally fixed, it was Bardsey Island, off the extreme westernmost point of Caernarvonshire, that was selected as his last abode. Into it he went with nine attendant bards, taking with him the "Thirteen Treasures of Britain", thenceforth lost to men. Bardsey Island no doubt derives its name from this story; and what is probably an allusion to it is found in a first-century Greek writer called Plutarch, who describes a grammarian called Demetrius as having visited Britain, and brought home an account of his travels. He mentioned several uninhabited and sacred islands off our coasts which he said were named after gods and heroes, but there was one especially in which Cronos was imprisoned with his attendant deities, and Briareus keeping watch over him as he slept; "for sleep was the bond forged for him".1 Doubtless this disinherited deity, whom the Greek, after his fashion, called "Cronos", was the British heaven- and sun-god, after he had descended into the prison of the west.

Among other new-corners is Kai, who, as Sir Kay the Seneschal, fills so large a part in the later romances. Purged of his worst offences, and reduced to a surly butler to Arthur, he is but a shadow of the earlier Kai who murdered Arthur's son Llacheu2, and can only be acquitted, through the obscurity of the poem that relates the incident, of having also carried off, or having tried to carry off, Arthur's wife, Gwynhwyvar.3 He is thought to have been a personification of fire,1 upon the strength of a description given of him in the mythical romance of "Kulhwch and Olwen". "Very subtle", it says, "was Kai. When it pleased him he could render himself as tall as the highest tree in the forest. And he had another peculiarity--so great was the heat of his nature, that, when it rained hardest, whatever he carried remained dry for a handbreadth above and a handbreadth below his hand; and when his companions were coldest, it was to them as fuel with which to light their fire."

Another personage who owes his prominence in the Arthurian story to his importance in Celtic myth was March son of Meirchion, whose swine Arthur attempted to steal, as Gwydion had done those of Pryderi. In the romances, he has become the cowardly and treacherous Mark, king, according to some stories, of Cornwall, but according to others, of the whole of Britain, and known to all as the husband of the Fair Isoult, and the uncle of Sir Tristrem. But as a deformed deity of the underworld2 he can be found in Gaelic as well as in British myth. He cannot be considered as originally different from Morc, a king of the Fomors at the time when from their Glass Castle they so fatally oppressed the Children of Nemed.3 The Fomors were distinguished by their animal features, and March had the same peculiarity.4 When Sir Thomas Malory relates how, to please Arthur and Sir Launcelot, Sir Dinadan made a song about Mark, "which was the worst lay that ever harper sang with harp or any other instruments",1 he does not tell us wherein the sting of the lampoon lay. It no doubt reminded King Mark of the unpleasant fact that he had--not like his Phrygian counterpart, ass's but--horse's ears. He was, in fact, a Celtic Midas, a distinction which he shared with one of the mythical kings of early Ireland.2

Neither can we pass over Urien, a deity of the underworld akin to, or perhaps the same as, Brân.3 Like that son of Llyr, he was at once a god of battle and of minstrelsy;4 he was adored by the bards as their patron;5 his badge was the raven (bran, in Welsh);6 while, to make his identification complete, there is an extant poem which tells how Urien, wounded, ordered his own head to be cut off by his attendants.7 His wife was Modron,8 known as the mother of Mabon, the sun-god to whom inscriptions exist as Maponos. Another of the children of Urien and Modron is Owain, which was perhaps only another name for Mabon.9 Taliesin calls him "chief of the glittering west",10 and he is as certainly a sun-god as his father Urien, "lord of the evening",11 was a ruler of the dark underworld.

It is by reason of the pre-eminence of Arthur that we find gathered round him so many gods, all probably various tribal personifications of the same few mythological ideas. The Celts, both of the Gaelic and the British branches, were split up into numerous petty tribes, each with its own local deities embodying the same essential conceptions under different names. There was the god of the underworld, gigantic in figure, patron alike of warrior and minstrel, teacher of the arts of eloquence and literature, and owner of boundless wealth, whom some of the British tribes worshipped as Brân, others as Urien, others as Pwyll, or March, or Mâth, or Arawn, or Ogyrvran. There was the lord of an elysium--Hades in its aspect of a paradise of the departed rather than of the primeval subterranean realm where all things originated--whom the Britons of Wales called Gwyn, or Gwynwas; the Britons of Cornwall, Melwas; and the Britons of Somerset, Avallon, or Avallach. Under this last title, his realm is called Ynys Avallon, "Avallon's Island", or, as we know the word, Avilion. It was said to be in the "Land of Summer", which, in the earliest myth, signified Hades; and it was only in later days that the mystic Isle of Avilion became fixed to earth as Glastonbury, and the Elysian "Land of Summer" as Somerset.1 There was a mighty ruler of heaven, a "god of battles", worshipped on high places, in whose hands was "the stern arbitrament of war"; some knew him as Lludd, others as Myrddin, or as Emrys.

There was a gentler deity, friendly to man, to help whom he fought or cajoled the powers of the underworld; Gwydion he was called, and Arthur. Last, perhaps, to be imagined in concrete shape, there was a long-armed, sharp-speared sun-god who aided the culture-god in his work, and was known as Lleu, or Gwalchmei, or Mabon, or Owain, or Peredur, and no doubt by many another name; and with him is usually found a brother representing not light, but darkness. This expression of a single idea by different names may be also observed in Gaelic myth, though not quite so clearly. In the hurtling of clan against clan, many such divinities perished altogether out of memory, or survived only as names, to make up, in Ireland, the vast, shadowy population claiming to be Tuatha Dé Danann, and, in Britain, the long list of Arthur's followers. Others--gods of stronger communities--would increase their fame as their worshippers increased their territory, until, as happened in Greece, the chief deities of many tribes came together to form a national Pantheon.

We have already tried to explain the "Coming of Arthur" historically. Mythologically, he came, as, according to Celtic ideas, all things came originally, from the underworld. His father is called Uther Pendragon.1 But Uther Pendragon is (for the word "dragon" is not part of the name, but a title signifying "war-leader") Uther Ben, that is, Brân, under his name of the "Wonderful Head",2 so that, in spite of the legend which describes Arthur as having disinterred Brân's head on Tower Hill, where it watched against invasion, because he thought it beneath his dignity to keep Britain in any other way than by valour,1 we must recognize the King of Hades as his father. This being so, it would only be natural that he should take a wife from the same eternal country, and we need not be surprised to find in Gwynhwyvar's father, Ogyrvran, a personage corresponding in all respects to the Celtic conception of the ruler of the underworld. He was of gigantic size;2 he was the owner of a cauldron out of which three Muses had been born;3 and he was the patron of the bards,4 who deemed him to have been the originator of their art. More than this, his very name, analysed into its original ocur vran, means the evil bran, or raven, the bird of death.5

But Welsh tradition credits Arthur with three wives, each of them called Gwynhwyvar. This peculiar arrangement is probably due to the Celtic love of triads; and one may compare them with the three Etains who pass through the mythico-heroic story of Eochaid Airem, Etain, and Mider. Of these three Gwynhwyvars,6 besides the Gwynhwyvar, daughter of Ogyrvran, one was the daughter of Gwyrd Gwent, of whom we know nothing but the name, and the other of Gwyrthur ap Greidawl, the same "Victor son of Scorcher" with whom Gwyn son of Nudd, fought, in earlier myth, perpetual battle for the possession of Creudylad, daughter of the sky-god Lludd. This same eternal strife between the powers of light and darkness for the possession of a symbolical damsel is waged again in the Arthurian cycle; but it is no longer for Creudylad that Gwyn contends, but for Gwynhwyvar, and no longer with Gwyrthur, but with Arthur. It would seem to have been a Cornish form of the myth; for the dark god is called "Melwas", and not "Gwynwas", or "Gwyn", his name in Welsh.1 Melwas lay in ambush for a whole year, and finally succeeded in carrying off Gwynhwyvar to his palace in Avilion. But Arthur pursued, and besieged that stronghold, just as Eochaid Airem had, in the Gaelic version of the universal story, mined and sapped at Mider's sídh of Bri Leith.2 Mythology, as well as history, repeats itself; and Melwas was obliged to restore Gwynhwyvar to her rightful lord.

It is not Melwas, however, that in the best-known versions of the story contends with Arthur for the love of Gwynhwyvar. The most widespread early tradition makes Arthur's rival his nephew Medrawt. Here Professor Rhys traces a striking parallel between the British legend of Arthur, Gwynhwyvar, and Medrawt, and the Gaelic story of Airem, Etain, and Mider.3 The two myths are practically counterparts; for the names of all the three pairs agree in their essential meaning. "Airem", like "Arthur", signifies the "Ploughman", the divine institutor of agriculture; "Etain", the "Shining One", is a fit parallel to "Gwynhwyvar", the "White Apparition"; while "Mider" and "Medrawt" both come from the same root, a word meaning "to hit", either literally, or else metaphorically, with the mind, in the sense of coming to a decision. To attempt to explain this myth is to raise the vexed question of the meaning of mythology. Is it day and dark that strive for dawn, or summer and winter for the lovely spring, or does it shadow forth the rescue of the grain that makes man's life from the devouring underworld by the farmer's wit? When this can be finally resolved, a multitude of Celtic myths will be explained. Everywhere arise the same combatants for the stolen bride; one has the attributes of light, the other is a champion of darkness.

Even in Sir Thomas Malory's version of the Arthurian story, taken by him from French romances far removed from the original tradition, we find the myth subsisting. Medrawt's original place as the lover of Arthur's queen had been taken in the romances by Sir Launcelot, who, if he was not some now undiscoverable Celtic god,1 must have been an invention of the Norman adapters. But the story which makes Medrawt Arthur's rival has been preserved in the account of how Sir Mordred would have wedded Guinevere by force, as part of the rebellion which he made against his king and uncle.1 This strife was Celtic myth long before it became part of the pseudo-history of early Britain. The triads2 tell us how Arthur and Medrawt raided each other's courts during the owner's absence. Medrawt went to Kelli Wic, in Cornwall, ate and drank everything he could find there, and insulted Queen Gwynhwyvar, in revenge for which Arthur went to Medrawt's court and killed man and beast. Their struggle only ended with the Battle of Camlan; and that mythical combat, which chroniclers have striven to make historical, is full of legendary detail. Tradition tells how Arthur and his antagonist shared their forces three times during the fight, which caused it to be known as one of the "Three Frivolous Battles of Britain", the idea of doing so being one of "Britain's Three Criminal Resolutions". Four alone survived the fray: one, because he was so ugly that all shrank from him, believing him to be a devil; another, whom no one touched because he was so beautiful that they took him for an angel; a third, whose great strength no one could resist; and Arthur himself, who, after revenging the death of Gwalchmei upon Medrawt, went to the island of Avilion to heal him of his grievous wounds.

And thence--from the Elysium of the Celts popular belief has always been that he will some day return. But just as the gods of the Gaels are said to dwell sometimes in the "Land of the Living", beyond the western wave, and sometimes in the palace of a hollow hill, so Arthur is sometimes thought to be in Avilion, and sometimes to be sitting with his champions in a charmed sleep in some secret place, waiting for the trumpet to be blown that shall call him forth to reconquer Britain. The legend is found in the Eildon Hills; in the Snowdon district; at Cadbury, in Somerset, the best authenticated Camelot; in the Vale of Neath, in South Wales; as well as in other places. He slumbers, but he has not died. The ancient Welsh poem called "The Verses of the Graves of the Warriors"1 enumerates the last resting-places of most of the British gods and demi-gods. "The grave of Gwydion is in the marsh of Dinlleu", the grave of Lieu Llaw Gyffes is "under the protection of the sea with which he was familiar", and "where the wave makes a sullen sound is the grave of Dylan"; we know the graves of Pryderi, of Gwalchmei, of March, of Mabon, even of the great Beli, but

"Not wise the thought--a grave for Arthur".2

312:1 A poem in praise of Geraint, the brave man from the region of Dyvnaint (Devon) . . . the enemy of tyranny and oppression", is contained in both the Black Book of Caermarthen and the Red Book of Hergest. "When Geraint was born, open were the gates of heaven", begins its last verse. It is translated in Vol. I of Skene, p. 267.

313:1 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 8.

313:2 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, pp. 40-41.

314:1 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 7.

314:2 "It is worthy of remark that the fame of Arthur is widely spread; he is claimed alike as a prince in Brittany, Cornwall, Wales, Cumberland, and the Lowlands of Scotland; that is to say, his fame is conterminous with the Brythonic race, and does not extend to the Gaels".--Chambers's Encyclopædia.

314:3 For Arthurian and Fenian parallels see Campbell's Popular Tales of the West Highlands.

316:1 See chap. I of Rhys's Arthurian Legend--"Arthur, Historical and Mythical".

316:2 A triad in the Hengwrt MS. 536, translated by Skene. It was Trystan who was watching the swine for his uncle, while the swineherd went with a message to Essylt (Iseult), "and Arthur desired one pig by deceit or by theft, and could not get it"

317:1 See note to chap. XXII--"The Treasures of Britain".

317:2 Book of Taliesin, poem xxx, Skene, Vol. I, p. 256.

317:3 In a probably very ancient poem embedded in the sixteenth-century Welsh romance called Taliesin, included by Lady Guest in her Mabinogion.

318:1 "The existence of a sixth-century bard of this name, a contemporary of the heroic stage of British resistance to the Germanic invaders, is well attested. A number of poems are found in mediæval Welsh MSS., chief among them the so-called Book of Taliesin, ascribed to this sixth-century poet. Some of these are almost as old as any remains of Welsh poetry, and may go back to the early tenth or the ninth century; others are productions of the eleventh, twelfth, and even thirteenth centuries."--Nutt: Notes to his (1902) edition of Lady Guest's Mabinogion.

318:2 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, p. 551.

318:3 "There can be little doubt but that the sixth-century bard succeeded to the form and attributes of a far older, a prehistoric, a mythic singer."--Nutt: Notes to Mabinogion.

318:4 I have been obliged to collate four different translators to obtain an acceptable version of what Mr. T. Stephens, in his Literature of the Kymri, calls "one of the least intelligible of the mythological poems". My authorities have been Skene, Stephens, Nash, and Rhys.

319:1 A form of the name Gwydion.

319:2 The name of Arthur's ship.

319:3 Revolving Castle.

319:4 Four-cornered Castle.

319:5 The Cold Place.

319:6 Castle of Revelry.

319:7 Kingly Castle.

320:1 Glass Castle.

320:2 Castle of Riches.

320:3 Meaning is unknown. See chap. XVI--"The Gods of the Britons".

320:4 Meaning is unknown. See chap. XX--"The Victories of Light over Darkness".

321:1 Unless they should be "the yellow and the brindled bull" mentioned in the story of Kulhwch and Olwen.

321:2 Book of Taliesin, poem XIV. The translation is by Rhys: Arthurian Legend. p. 301.

322:1 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 325.

322:2 Rhys: ibid., chap. I.

323:1 Malory's Morte Darthur, Book II, chap. 11.

323:2 Historia Britonum, Book VIII, chap. xx.

323:3 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 169.

323:4 Rhys: ibid., p 169.

323:5 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 13.

323:6 Rhys: ibid., pp. 19-23.

323:7 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, p. 168.

324:1 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, p. 167.

324:2 See Rhys's exposition of the mythological meaning of the Red Book romance of the Dream of Maxen Wledig, in his Hibbert Lectures, pp. 160-175.

324:3 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, pp. 192-195.

324:4 Historia Britonum, Book VIII, chaps. IX-XII.

325:1 See chap. IV and Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, p. 194.

325:2 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, pp. 158, 159.

325:3 Ibid., p. 155.

326:1 Plutarch: De Defectu Oraculorum.

326:2 The Seint Greal, quoted by Rhys: Arthurian Legend, pp. 61-62.

326:3 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 59.

327:1 Elton: Origins of English History, p. 269.

327:2 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 12.

327:3 Ibid., p.70.

327:4 The name March means "horse".

328:1 Morte Darthur. Book X, chap. XXVII.

328:2 Called Labraid Longsech.

328:3 Rhys: Arthurian Legend. See chap. XI--"Urien and his Congeners".

328:4 Ibid., p. 260.

328:5 Ibid., p. 261.

328:6 Ibid., p. 256.

328:7 Red Book of Hergest, XII. Rhys: Arthurian Legend, pp. 253-256.

328:8 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 247.

328:9 Ibid.

328:10 The Death-song of Owain. Taliesin, XLIV, Skene, Vol. I, p. 366.

328:11 Book of Taliesin, XXXII. Skene, however, translates the word rendered "evening" by Rhys as "cultivated plain".

329:1 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 345.

330:1 Both by Malory and Geoffrey of Monmouth.

330:2 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 256.

331:1 See chap. XVIII--"The Wooing of Branwcn and the Beheading of Bryn".

331:2 He is called Ogyrvran the Giant.

331:3 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 326.

331:4 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, pp. 268-269.

331:5 Rhys: Lectures on Welsh Philology, p. 306. But the derivation is only tentative, and an interesting alternative one is given, which equates him with the Persian Ahriman.

331:6 The enumeration of Arthur's three Gwynhwyvars forms one of the Welsh triads.

332:1 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, p. 342.

332:2 See chap. XI--"The Gods in Exile".

332:3 Rhys: Arthurian Legend, chap. II--"Arthur and Airem".

333:1 In the mysterious Lancelot, not found in Arthurian story before the Norman adaptations of it, Professor Rhys is inclined to see a British sun-god, or solar hero. A number of interesting comparisons are drawn between him and the Peredur and Owain of the later "Mabinogion" tales, as well as with the Gaelic Cuchulainn. See Studies in the Arthurian Legend.

334:1 Morte Darthur, Book XXI, chap. I.

334:2 The fullest list of translated triads is contained in the appendix to Probert's Ancient Laws of Cambria, 1823. Many are also given as an appendix in Skene's Four Ancient Books of Wales.

335:1 Black Book of Caermarthen XIX, Vol. I, pp. 309-318 in Skene.

335:2 This is Professor Rhys's translation of the Welsh line, no doubt more strictly correct than the famous rendering: "Unknown is the grave of Arthur".