Celtic Myth and Legend Poetry and Romance

by Charles Squire

CHAPTER XI

THE GODS IN EXILE

But though mortals had conquered gods upon a scale unparalleled in mythology, they had by no means entirely subdued them. Beaten in battle, the people of the goddess Danu had yet not lost their divine attributes, and could use them either to help or hurt. "Great was the power of the Dagda", says a tract preserved in the Book of Leinster, "over the sons of Milé, even after the conquest of Ireland; for his subjects destroyed their corn and milk, so that they must needs make a treaty of peace with the Dagda. Not until then, and thanks to his. good-will, were they able to harvest corn and drink the milk of their cows."1 The basis of this lost treaty seems to have been that the Tuatha Dé Danann, though driven from the soil, should receive homage and offerings from their successors. We are told in the verse dinnsenchus of Mag Slecht, that--

Of Eremon, the noble man of grace,

There was worshipping of stones

Until the coming of good Patrick of Macha".2

Dispossessed of upper earth, the gods had, however, to seek for new homes. A council was convened, but its members were divided between two opinions. One section of them chose to shake the dust of Ireland off its disinherited feet, and seek refuge in a paradise over-seas, situate in some unknown, and, except for favoured mortals, unknowable island of the west, the counterpart in Gaelic myth of the British

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadow'd, happy, fair with orchard-lawns

And bowery hollows crown'd with summer sea"1

--a land of perpetual pleasure and feasting, described variously as the "Land of Promise" (Tir Tairngiré), the "Plain of Happiness" (Mag Mell), the "Land of the Living" (Tir-nam-beo), the "Land of the Young" (Tir-nan-ōg), and "Breasal's Island" (Hy-Breasail). Celtic mythology is full of the beauties and wonders of this mystic country, and the tradition of it has never died out. Hy-Breasail has been set down on old maps as a reality again and again;2 some pioneers in the Spanish seas thought they had discovered it, and called the land they found "Brazil"; and it is still said, by lovers of old lore, that a patient watcher, after long gazing westward from the westernmost shores of Ireland or Scotland, may sometimes be lucky enough to catch a glimpse against the sunset of its--

Of these divine emigrants the principal was Manannán son of Lêr. But, though he had cast in his lot beyond the seas, he did not cease to visit Ireland. An old Irish king, Bran, the son of Febal, met him, according to a seventh-century poem, as Bran journeyed to, and Manannán from, the earthly paradise. Bran was in his boat, and Manannán was driving a chariot over the tops of the waves, and he sang:1

"Bran deems it a marvellous beauty

In his coracle across the clear sea:

While to me in my chariot from afar

It is a flowery plain on which he rides about.

"What is a clear sea

For the prowed skiff in which Bran is,

That is a happy plain with profusion of flowers

To me from the chariot of two wheels.

"Bran sees

The number of waves beating across the clear sea:

I myself see in Mag Mon2

Red-headed flowers without fault.

"Sea-horses glisten in summer

As far as Bran has stretched his glance:

Rivers pour forth a stream of honey

In the land of Manannán son of Lêr.

"The sheen of the main, on which thou art,

The white hue of the sea, on which thou rowest about,

Yellow and azure are spread out,

It is land, and is not rough.

"Speckled salmon leap from the womb

Of the white sea, on which thou lookest:

They are calves, they are coloured lambs

With friendliness, without mutual slaughter.

"Though but one chariot-rider is seen

In Mag Mell1 of many flowers,

There are many steeds on its surface,

Though them thou seest not.

"Along the top of a wood has swum

Thy coracle across ridges,

There is a wood of beautiful fruit

Under the prow of thy little skiff.

"A wood with blossom and fruit,

On which is the vine's veritable fragrance;

A wood without decay, without defect,

On which are leaves of a golden hue."

And, after this singularly poetical enunciation of the philosophical and mystical doctrine that all things are, under their diverse forms, essentially the same, he goes on to describe to Bran the beauties and pleasures of the Celtic Elysium.

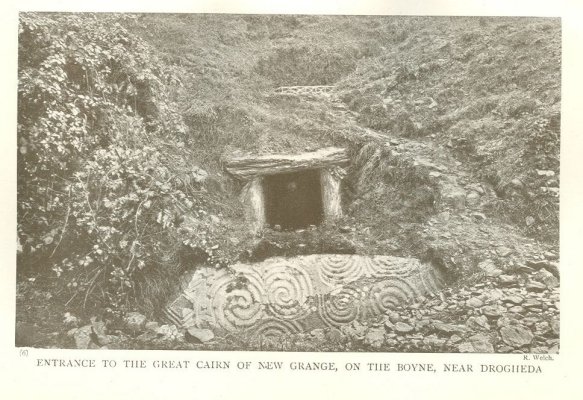

But there were others--indeed, the most part--of the gods who refused to expatriate themselves. For these residences had to be found, and the Dagda, their new king, proceeded to assign to each of those who stayed in Ireland a sídh. These sídhe were barrows, or hillocks, each being the door to an underground realm of inexhaustible splendour and delight, according to the somewhat primitive ideas of the Celts. A description is given of one which the Dagda kept for himself, and out of which his son Angus cheated him, which will serve as a fair example of all. There were apple-trees there always in fruit, and one pig alive and another ready roasted, and the supply of ale never failed. One may still visit in Ireland the sídhe of many of the gods, for the spots are known, and the traditions have not died out. To Lêr was given Sídh Fionnachaidh1, now known as the "Hill of the White Field", on the top of Slieve Fuad, near Newtown Hamilton, in County Armagh. Bodb Derg received a sídh called by his own name, Sídh Bodb2, just to the south of Portumna, in Galway. Mider was given the sídh of Bri Leith, now called Slieve Golry, near Ardagh, in County Longford. Ogma's sídh was called Airceltrai; to Lugh was assigned Rodrubân; Manannán's son, Ilbhreach, received Sídh Eas Aedha Ruaidh3, now the Mound of Mullachshee, near Ballyshannon, in Donegal; Fionnbharr4 had Sídh Meadha, now "Knockma", about five miles west of Tuam, where, as present king of the fairies, he is said to live to-day; while the abodes of other gods of lesser fame are also recorded. For himself the Dagda retained two, both near the River Boyne, in Meath, the best of them being the famous Brugh-na-Boyne. None of the members of the Tuatha Dé Danann were left unprovided for, save one.

ENTRANCE TO THE GREAT CAIRN OF NEW GRANGE, ON THE BOYNE, NEAR DROGHEDA.--R. Welch

It was from this time that the Gaelic gods received the name by which the peasantry know them to-day--Aes Sídhe, the "People of the Hills", or, more shortly, the Sídhe. Every god, or fairy, is a Fer-Sídhe1, a "Man of the Hill"; and every goddess a Bean-Sídhe, a "Woman of the Hill", the banshee of popular legend.2

The most famous of such fairy hills are about five miles from Drogheda.3 They are still connected with the names of the Tuatha Dé Danann, though they are now not called their dwelling-places, but their tombs. On the northern bank of the Boyne stand seventeen barrows, three of which--Knowth, Dowth, and New Grange--are of great size. The last named, largest, and best preserved, is over 300 feet in diameter, and 70 feet high, while its top makes a platform 120 feet across. It has been explored, and Roman coins, gold torques, copper pins, and iron rings and knives have been found in it; but what else it may have once contained will never be known, for, like Knowth and Dowth, it was thoroughly ransacked by Danish spoilers in the ninth century. It is entered by a square doorway, the rims of which are elaborately ornamented with a kind of spiral pattern. This entrance leads to a stone passage, more than 60 feet long, which gradually widens and rises, until it opens into a chamber with a conical dome 20 feet high. On each side of this central chamber is a recess, with a shallow oval stone basin in it. The huge slabs of which the whole is built are decorated upon both the outer and the inner faces with the same spiral pattern as the doorway.

The origin of these astonishing prehistoric monuments is unknown, but they are generally attributed to the race that inhabited Ireland before the Celts. Gazing at marvellous New Grange, one might very well echo the words of the old Irish poet Mac Nia, in the Book of Ballymote:

It is manifest to you that it is a king's mansion,

Which was built by the firm Dagda,

It was a wonder, a court, an admirable hill."1

It is not, however, with New Grange, or even with Knowth or Dowth, that the Dagda's name is now associated. It is a smaller barrow, nearer to the Boyne, which is known as the "Tomb of the Dagda". It has never been opened, and Dr. James Fergusson, the author of Rude Stone Monuments, who holds the Tuatha Dé Danann to have been a real people, thinks that "the bones and armour of the great Dagda may still be found in his honoured grave".2 Other Celtic scholars might not be so sanguine, though verses as old as the eleventh century assert that the Tuatha Dé Danann used the brughs for burial. It was about this period that the mythology of Ireland was being rewoven into spurious history. The poem, which is called the "Chronicles of the Tombs", not only mentions the "Monument of the Dagda" and the "Monument of the Morrígú", but also records the last resting-places of Ogma, Etain, Cairpré, Lugh, Boann, and Angus.

We have for the present, however, to consider Angus in a far less sepulchral light. He is, indeed, very much alive in the story to be related. The "Son of the Young" was absent when the distribution of the sídhe was made. When he returned, he came to his father, the Dagda, and demanded one. The Dagda pointed out to him that they had all been given away. Angus protested, but what could be done? By fair means, evidently nothing; but by craft, a great deal. The wily Angus appeared to reconcile himself to fate, and only begged his father to allow him to stay at the sídh of Brugh-na-Boyne (New Grange) for a day and a night. The Dagda agreed to this, no doubt congratulating himself on having got out of the difficulty so easily. But when he came to Angus to remind him that the time was up, Angus refused to go. He had been granted, he claimed, day and night, and it is of days and nights that time and eternity are composed; therefore there was no limit to his tenure of the sídhe. The logic does not seem very convincing to our modern minds, but the Dagda is said to have been satisfied with it. He abandoned the best of his two palaces to his son, who took peaceable possession of it. Thus it got a second name, that of the Sídh or Brugh of the "Son of the Young".1

The Dagda does not, after this, play much active part in the history of the people of the goddess Danu. We next hear of a council of gods to elect a fresh ruler. There were five candidates for the vacant throne--Bodb the Red, Mider, Ilbhreach1 son of Manannán, Lêr, and Angus himself, though the last-named, we are told, had little real desire to rule, as he preferred a life of freedom to the dignities of kingship. The Tuatha Dé Danann went into consultation, and the result of their deliberation was that their choice fell upon Bodb the Red, for three reasons--firstly, for his own sake; secondly, for his father, the Dagda's sake; and thirdly, because he was the Dagda's eldest son. The other competitors approved this choice, except two. Mider refused to give hostages, as was the custom, to Bodb Derg, and fled with his followers to "a desert country round Mount Leinster", in County Carlow, while Lêr retired in great anger to Sídh Fionnachaidh, declining to recognize or obey the new king.

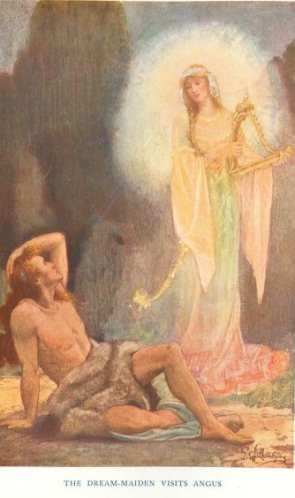

Why Lêr and Mider should have so taken the matter to heart is difficult to understand, unless it was because they were both among the oldest of the gods. The indifference of Angus is easier to explain. He was the Gaelic Eros, and was busy living up to his character. At this time, the object of his love was a maiden who had visited him one night in a dream, only to vanish when he put out his arms to embrace her. All the next day, we are told, Angus took no food.

Upon the following night, the unsubstantial lady again appeared, and played and sang to him. That following day, he also fasted. So things went on for a year, while Angus pined and wasted for love. At last the physicians of the Tuatha Dé Danann guessed his complaint, and told him how fatal it might be to him. Angus asked that his mother Boann might be sent for, and, when she came, he told her his trouble, and implored her help. She went to the Dagda and begged him, if he did not wish to see his son die of unrequited love, a disease that all Diancecht's medicine and Goibniu's magic could not heal, to find the dream-maiden. The Dagda could do nothing himself, but he sent to Bodb the Red, and the new king of the gods sent in turn to the lesser deities of Ireland, ordering all of them to search for her. For a year she could not be found, but at last the disconsolate lover received a message, charging him to come and see if he could recognize the lady of his dreams. Angus came, and knew her at once, even though she was surrounded by thrice fifty attendant nymphs. Her name was Caer, and she was the daughter of Etal Ambuel, who had a sídh at Uaman, in Connaught. Bodb the Red demanded her for Angus in marriage, but her father declared that he had no control over her. She was a swan-maiden, he said; and every year, as soon as summer was over, she went with her companions to a lake called "Dragon-Mouth", and there all of them became swans. But, refusing to be thus put off, Angus waited in patience until the day of the magical change, and then went down to the shore of the lake. There, surrounded by thrice fifty swans, he saw Caer, herself a swan surpassing all the rest in beauty and whiteness. He called to her, proclaiming his passion and his name, and she promised to be his bride, if he too would become a swan. He agreed, and with a word she changed him into swan-shape, and thus they flew side by side to Angus's sídhe, where they retook the human form, and, no doubt, lived happily as long as could be expected of such changeable immortals as pagan deities.1

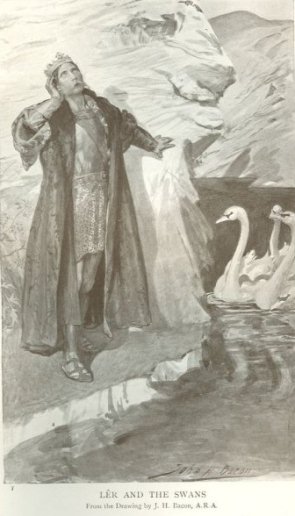

Meanwhile, the people of the goddess Danu were justly incensed against both Lêr and Mider. Bodb the Red made a yearly war upon Mider in his sídhe, and many of the divine race were killed on either side. But against Lêr, the new king of the gods refused to move, for there had been a great affection between them. Many times Bodb Derg tried to regain Lêr's friendship by presents and compliments, but for a long time without success.

At last Lêr's wife died, to the sea-god's great sorrow. When Bodb the Red heard the news, he sent a messenger to Lêr, offering him one of his own foster-daughters, Aebh2, Aeife3, and Ailbhe4, the children of Ailioll of Arran. Lêr, touched by this, came to visit Bodb the Red at his sídhe, and chose Aebh for his wife. "She is the eldest, so she must be the noblest of them," he said. They were married, and a great feast made, and Lêr took her back with him to Sídh Fionnachaidh.

Aebh bore four children to Lêr. The eldest was a daughter called Finola, the second was a son called Aed; the two others were twin boys called Fiachra and Conn, but in giving birth to those Aebh died.

Bodb the Red then offered Lêr another of his foster-children, and he chose the second, Aeife. Every year Lêr and Aeife and the four children used to go to Manannán's "Feast of Age", which was held at each of the sídhe in turn. The four children grew up to be great favourites among the people of the goddess Danu.

But Aeife was childless, and she became jealous of Lêr's children; for she feared that he would love them more than he did her. She brooded over this until she began, first to hope for, and then to plot their deaths. She tried to persuade her servants to murder them, but they would not. So she took the four children to Lake Darvra (now called Lough Derravargh in West Meath), and sent them into the water to bathe. Then she made an incantation over them, and touched them, each in turn, with a druidical wand, and changed them into swans.

But, though she had magic enough to alter their shapes, she had not the power to take away their human speech and minds. Finola turned, and threatened her with the anger of Lêr and of Bodb the Red when they came to hear of it. She, however, hardened her heart, and refused to undo what she had done. The children of Lêr, finding their case a hopeless one, asked her how long she intended to keep them in that condition.

"You would be easier in mind," she said, "if you had not asked the question; but I will tell you.

You shall be three hundred years here, on Lake Darvra; and three hundred years upon the Sea of Moyle1, which is between Erin and Alba; and three hundred years more at Irros Domnann2 and the Isle of Glora in Erris3. Yet you shall have two consolations in your troubles; you shall keep your human minds, and yet suffer no grief at knowing that you have been changed into swans, and you shall be able to sing the softest and sweetest songs that were ever heard in the world."

Then Aeife went away and left them. She returned to Lêr, and told him that the children had fallen by accident into Lake Darvra, and were drowned.

But Lêr was not satisfied that she spoke the truth, and went in haste to the lake, to see if he could find traces of them. He saw four swans close to the shore, and heard them talking to one another with human voices. As he approached, they came out of the water to meet him. They told him what Aeife had done, and begged him to change them back into their own shapes. But Lêr's magic was not so powerful as his wife's, and he could not.

Nor even could Bodb the Red--to whom Lêr went for help,--for all that he was king of the gods. What Aeife had done could not be undone. But she could be punished for it! Bodb ordered his foster-daughter to appear before him, and, when she came, he put an oath on her to tell him truly "what shape of all others, on the earth, or above the earth, or beneath the earth, she most abhorred, and into which she most dreaded to be transformed".

Aeife was obliged to answer that she most feared to become a demon of the air. So Bodb the Red struck her with his wand, and she fled from them, a shrieking demon.

All the Tuatha Dé Danann went to Lake Darvra to visit the four swans. The Milesians heard of it, and also went; for it was not till long after this that gods and mortals ceased to associate. The visit became a yearly feast. But, at the end of three hundred years, the children of Lêr were compelled to leave Lake Darvra, and go to the Sea of Moyle, to fulfil the second period of their exile.

They bade farewell to gods and men, and went. And, for fear lest they might be hurt by anyone, the Milesians made it law in Ireland that no man should harm a swan, from that time forth for ever.

The children of Lêr suffered much from tempest and cold on the stormy Sea of Moyle, and they were very lonely. Once only during that long three hundred years did they see any of their friends. An embassy of the Tuatha Dé Danann, led by two sons of Bodb the Red, came to look for them, and told them all that had happened in Erin during their exile.

At last that long penance came to an end, and they went to Irros Domnann and Innis Glora for their third stage. And while it was wearily dragging through, Saint Patrick came to Ireland, and put an end to the power of the gods for ever. They had been banned and banished when the children of Lêr found themselves free to return to their old home. Sídh Fionnechaidh was empty and deserted, for Lêr had been killed by Caoilté, the cousin of Finn mac Coul.1

So, after long, vain searching for their lost relatives, they gave up hope, and returned to the Isle of Glora. They had a friend there, the Lonely Crane of Inniskea2, which has lived upon that island ever since the beginning of the world, and will be still sitting there on the day of judgment. They saw no one else until, one day, a man came to the island. He told them that he was Saint Caemhoc3, and that he had heard their story. He brought them to his church, and preached the new faith to them, and they believed on Christ, and consented to be baptised. This broke the pagan spell, and, as soon as the holy water was sprinkled over them, they returned to human shape. But they were very old and bowed--three aged men and an ancient woman. They did not live long after this, and Saint Caemhoc, who had baptised them, buried them all together in one grave.4

But, in telling this story, we have leaped nine hundred years--a great space in the history even of gods. We must retrace our steps, if not quite to the days of Eremon and Eber, sons of Milé, and first kings of Ireland, at any rate to the beginning of the Christian era.

At this time Eochaid Airem was high king of Ireland, and reigned at Tara; while, under him, as vassal monarchs, Conchobar mac Nessa ruled over the Red Branch Champions of Ulster; Curoi son of Daire1, was king of Munster; Mesgegra was king of Leinster; and Ailell, with his famous queen, Medb, governed Connaught.

Shortly before, among the gods, Angus Son of the Young, had stolen away Etain, the wife of Mider. He kept her imprisoned in a bower of glass, which he carried everywhere with him, never allowing her to leave it, for fear Mider might recapture her. The Gaelic Pluto, however, found out where she was, and was laying plans to rescue her, when a rival of Etain's herself decoyed Angus away from before the pleasant prison-house, and set his captive free. But, instead of returning her to Mider, she changed the luckless goddess into a fly, and threw her into the air, where she was tossed about in great wretchedness at the mercy of every wind.

At the end of seven years, a gust blew her on to the roof of the house of Etair, one of the vassals of Conchobar, who was celebrating a feast. The unhappy fly, who was Etain, was blown down the chimney into the room below, and fell, exhausted, into a golden cup full of beer, which the wife of the master of the house was just going to drink. And the woman drank Etain with the beer.

But, of course, this was not the end of her--for the gods cannot really die,--but only the beginning of a new life. Etain was reborn as the daughter of Etair's wife, no one knowing that she was not of mortal lineage. She grew up to be the most beautiful woman in Ireland.

When she was twenty years old, her fame reached the high king, who sent messengers to see if she was as fair as men reported. They saw her, and returned to the king full of her praises. So Eochaid himself went to pay her a visit. He chose her to be his queen, and gave her a splendid dowry.

It was not till then that Mider heard of her. He came to her in the shape of a young man, beautifully dressed, and told her who she really was, and how she had been his wife among the people of the goddess Danu. He begged her to leave the king, and come with him to his sídh at Bri Leith. But Etain refused with scorn.

"Do you think," she said, "that I would give up the high king of Ireland for a person whose name and kindred I do not know, except from his own lips?"

The god retired, baffled for the time. But one day, as King Eochaid sat in his hall, a stranger entered. He was dressed in a purple tunic, his hair was like gold, and his eyes shone like candles.

The king welcomed him.

"But who are you?" he asked; "for I do not know you."

"Yet I have known you a long time," returned the stranger.

"Then what is your name?"

"Not a very famous one. I am Mider of Bri Leith."

"Why have you come here?"

"To challenge you to a game of chess."

"I am a good chess-player," replied the king, who was reputed to be the best in Ireland.

"I think I can beat you," answered Mider.

"But the chess-board is in the queen's room, and she is asleep," objected Eochaid.

"It does not matter," replied Mider. "I have brought a board with me which can be in no way worse than yours."

He showed it to the king, who admitted that the boast was true. The chess-board was made of silver set in precious stones, and the pieces were of gold.

"Play!" said Mider to the king.

"I never play without a wager," replied Eochaid.

"What shall be the stake?" asked Mider.

"I do not care," replied Eochaid.

"Good!" returned Mider. "Let it be that the loser pays whatever the winner demands."

"That is a wager fit for a king," said Eochaid.

They played, and Mider lost. The stake that Eochaid claimed from him was that Mider and his subjects should make a road through Ireland. Eochaid watched the road being made, and noticed how Mider's followers yoked their oxen, not by the horns, as the Gaels did, but at the shoulders, which was better. He adopted the practice, and thus got his nickname, Airem, that is, The Ploughman".

After a year, Mider returned and challenged the king again, the terms to be the same as before. Eochaid agreed with joy; but, this time, he lost.

"I could have beaten you before, if I had wished," said Mider, "and now the stake I demand is Etain, your queen."

The astonished king, who could not for shame go back upon his word, asked for a year's delay. Mider agreed to return upon that day year to claim Etain. Eochaid consulted with his warriors, and they decided to keep watch through the whole of the day fixed by Mider, and let no one pass in or out of the royal palace till sunset. For Eochaid held that if the fairy king could not get Etain upon that one day, his promise would be no longer binding on him.

So, when the day came, they barred the door and guarded it, but suddenly they saw Mider among them in the hall. He stood beside Etain, and sang this song to her, setting out the pleasures of the homes of the gods under the enchanted hills.

"O fair lady! will you come with me

To a wonderful country which is mine,

Where the people's hair is of golden hue,

And their bodies the colour of virgin snow?

"There no grief or care is known;

White are their teeth, black their eyelashes;

Delight of the eye is the rank of our hosts,

With the hue of the fox-glove on every cheek.

"Crimson are the flowers of every mead,

Gracefully speckled as the blackbird's egg;

Though beautiful to see be the plains of Inisfail1

They are but commons compared to our great plains.

"Though intoxicating to you be the ale-drink of Inisfail,

More intoxicating the ales of the great country;

The only land to praise is the land of which I speak,

Where no one ever dies of decrepit age.

"Soft sweet streams traverse the land;

The choicest of mead and of wine;

Beautiful people without any blemish;

Love without sin, without wickedness.

"We can see the people upon all sides,

But by no one can we be seen;

The cloud of Adam's transgression it is

That prevents them from seeing us.

"O lady, should you come to my brave land,

It is golden hair that will be on your head;

Fresh pork, beer, new milk, and ale,

You there with me shall have, O fair lady!"1

Then Mider greeted Eochaid, and told him that he had come to take away Etain, according to the king's wager. And, while the king and his warriors looked on helplessly, he placed one arm round the now willing woman, and they both vanished. This broke the spell that hung over everyone in the hall; they rushed to the door, but all they could see were two swans flying away.

The king would not, however, yield to the god. He sent to every part of Ireland for news of Etain, but his messengers all came back without having been able to find her. At last, a druid named Dalân learned, by means of ogams carved upon wands of yew, that she was hidden under Mider's sídh of Bri Leith. So Eochaid marched there with an army, and began to dig deep into the abode of the gods of which the "fairy hill" was the portal. Mider, as terrified as was the Greek god Hades when it seemed likely that the earth would be rent open,1 and his domains laid bare to the sight, sent out fifty fairy maidens to Eochaid, every one of them having the appearance of Etain. But the king would only be content with the real Etain, so that Mider, to save his sídh, was at last obliged to give her up. And she lived with the King of Ireland after that until the death of both of them.

But Mider never forgave the insult. He bided his time for three generations, until Eochaid and Etain had a male descendant. For they had no son, but only a daughter called Etain, like her mother, and this second Etain had a daughter called Messbuachallo, who had a son called Conairé, surnamed "the Great". Mider and the gods wove the web of fate round Conairé, so that he and all his men died violent deaths.2

132:1 De Jubainville: Cycle Mythologique Irlandais, p. 269.

132:2 See chap. IV--"The Religion of the Ancient Britons and Druidism".

133:1 Tennyson: Idylls of the King: The Passing of Arthur.

133:2 See Wood-Martin: Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland, Vol. I, pp. 213-215.

134:1 The following verses are taken from Dr. Kuno Meyer's translation of the romance entitled The Voyage of Bran, Son of Febal, published in Mr. Nutt's Grimm Library, Vol. IV.

134:2 The Plain of Sports.

135:1 The Happy Plain.

136:1 Pronounced Shee Finneha.

136:2 Pronounced Shee Bove.

136:3 Pronounced Shee Assaroe.

136:4 Pronounced Finnvar.

137:1 Pronounced Far-shee.

137:2 O'Curry: Lectures on the MS. Materials of Ancient Irish History, Appendix p. 505.

137:3 See Fergusson: Rude Stone Monuments, pp. 200-213.

138:1 O'Curry: MS. Materials, p. 505.

138:2 Fergusson: Rude Stone Monuments, p. 209.

139:1 This story is contained in the Book of Leinster.

140:1 Pronounced Ilbrec.

142:1 This story, called the Dream of Angus, will be found translated into English by Dr. Edward Müller in Vol. III. of the Revue Celtique, from an eighteenth-century MS. in the British Museum.

142:2 Pronounced Aive.

142:3 Pronounced Aiva.

142:4 Pronounced Alva.

144:1 Now called "North Channel"

144:2 The Peninsula of Ems, in Mayo.

144:3 A small island off Benmullet.

146:1 See chap. XIV--"Finn and the Fenians".

146:2 An island off the coast of Mayo. Its lonely crane was one of the "Wonders of Ireland", and is still an object of folk-belief.

146:3 Pronounced Kemoc.

146:4 This famous story of the Fate of the Children of Lêr is not found in any MS. earlier than the beginning of the seventeenth century. A translation of it has been published by Eugene O'Curry in Atlantis, Vol. IV, from which the present abridgment is made.

147:1 Pronounced Dara.

150:1 A poetical name for Ireland.

151:1 Translated by O'Curry, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, Lecture IX, p. 192, 193.

152:1 Iliad, Book XX.

152:2 The story of Mider's revenge and Conairé's death is told in the romance Bruidhen Dá Derga, "The Destruction of Da Derga 's Fort", translated by Dr. Whitley Stokes, Eugene O'Curry and Professor Zimmer from the original text.

Index | Next: Chapter XII. The Irish Iliad