Celtic Myth and Legend Poetry and Romance

by Charles Squire

CHAPTER XIV

FINN AND THE FENIANS*

The epoch of Emain Macha is followed in the annals of ancient Ireland by a succession of monarchs who, though doubtless as mythical as King Conchobar and his court, seem to grow gradually more human. Their line lasts for about two centuries, culminating in a dynasty with which legend has occupied itself more than with its immediate predecessors. This is the one which began, according to the annalists, in A.D. 177, with the famous Conn "the Hundred-Fighter", and, passing down to the reign of his even more famous grandson, Cormac "the Magnificent", is connected with the third Gaelic cycle--that which relates the exploits of Finn and the Fenians. All these kings had their dealings with the national gods. A story contained in a fifteenth-century Irish manuscript, and called "The Champion's Prophecy",2 tells how Lugh appeared to Conn, enveloped him in a magic mist, led him away to an enchanted palace, and there prophesied to him the number of his descendants, the length of their reigns, and the manner of their deaths. Another tradition relates how Conn's son, Connla, was wooed by a goddess and borne away, like the British Arthur, in a boat of glass to the Earthly Paradise beyond the sea.1 Yet another relates Conn's own marriage with Becuma of the Fair Skin, wife of that same Labraid of the Quick Hand on Sword who, in another legend, married Liban, the sister of Fand, Cuchulainn's fairy love. Becuma had been discovered in an intrigue with Gaiar, a son of Manannán, and, banished from the "Land of Promise", crossed the sea that sunders mortals and immortals to offer her hand to Conn. The Irish king wedded her, but evil came of the marriage. She grew jealous of Conn's other son, Art, and insisted upon his banishment; but they agreed to play chess to decide which should go, and Art won. Art, called "the Lonely" because he had lost his brother Connla, was king after Conn, but he is chiefly known to legend as the father of Cormac.

Many Irish stories occupy themselves with the fame of Cormac, who is pictured as a great legislator--a Gaelic Solomon. Certain traditions credit him with having been the first to believe in a purer doctrine than the Celtic polytheism, and even with having attempted to put down druidism, in revenge for which a druid called Maelcen sent an evil spirit who placed a salmon-bone crossways in the king's throat, as he sat at meat, and so compassed his death. Another class of stories, however, make him an especial favourite with those same heathen deities. Manannán son of Lêr, was so anxious for his friendship that he decoyed him into fairyland, and gave him a magic branch. It was of silver, and bore golden apples, and, when it was shaken, it made such sweet music that the wounded, the sick, and the sorrowful forgot their pains, and were lulled into deep sleep. Cormac kept this treasure all his life; but, at his death, it returned into the hands of the gods.1

King Cormac was a contemporary of Finn mac Coul2, whom he appointed head of the Fianna3 Eirinn, more generally known as the "Fenians". Around Finn and his men have gathered a cycle of legends which were equally popular with the Gaels of both Scotland and Ireland. We read of their exploits in stories and poems preserved in the earliest Irish manuscripts, while among the peasantry both of Ireland and of the West Highlands their names and the stories connected with them are still current lore. Upon some of these floating traditions, as preserved in folk ballads, MacPherson founded his factitious Ossian, and the collection of them from the lips of living men still affords plenty of employment to Gaelic students.

How far Finn and his followers may have been historical personages it is impossible to say. The Irish people themselves have always held that the Fenians were a kind of native militia, and that Finn was their general. The early historical writers of Ireland supported this view. The chronicler Tighernach, who died in 1088, believed in him, and the "Annals of the Four Masters", compiled between the years 1632 and 1636 from older chronicles, while they ignore King Conchobar and his Red Branch Champions as unworthy of the serious consideration of historians, treat Finn as a real person whose death took place in 283 A.D. Even so great a modern scholar as Eugene O'Curry declared in the clearest language that Finn, so far from being "a merely imaginary or mythical character", was "an undoubtedly historical personage; and that he existed about the time at which his appearance is recorded in the Annals is as certain as that Julius Caesar lived and ruled at the time stated on the authority of the Roman historians".1

The opinion of more recent Celtic scholars, however, is opposed to this view. Finn's pedigree, preserved in the Book of Leinster, may seem at first to give some support to the theory of his real existence, but, on more careful examination of it, his own name and that of his father equally bewray him. Finn or Fionn, meaning "fair", is the name of one of the mythical ancestors of the Gaels, while his father's name, Cumhal2, signifies the "sky", and is the same word as Camulus, the Gaulish heaven-god identified by the Romans with Mars. His followers are as doubtfully human as himself. One may compare them with Cuchulainn and the rest of the heroes of Emain Macha. Their deeds are not less marvellous.

Like the Ultonian warriors, they move, too, on equal terms with the gods. "The Fianna of Erin", says a tract called "The Dialogue of the Elders",1 contained in thirteenth and fourteenth century manuscripts, "had not more frequent and free intercourse with the men of settled habitation than with the Tuatha Dé Danann".2 Angus, Mider, Lêr, Manannán, and Bodb the Red, with their countless sons and daughters, loom as large in the Fenian, or so-called "Ossianic" stories as do the Fenians themselves. They fight for them, or against them; they marry them, and are given to them in marriage.

A luminous suggestion of Professor Rhys also hints that the Fenians inherited the conduct of that ancient war formerly waged between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomors. The most common antagonists of Finn and his heroes are tribes of invaders from oversea, called in the stories the Lochlannach. These "Men of Lochlann" are usually identified, by those who look for history in the stories of the Fenian cycle, with the invading bands of Norsemen who harried the Irish coasts in the ninth century. But the nucleus of the Fenian tales antedates these Scandinavian raids, and mortal foes have probably merely stepped into the place of those immortal enemies of the gods whose "Lochlann" was a country, not over the sea--but under it.3

The earlier historians of Ireland were as ready with their dates and facts regarding the Fenian band as an institution as with the personality of Finn. It was said to have been first organized by a king called Fiachadh, in 300 B.C., and abolished, or rather, exterminated, by Cairbré, the son of Cormac mac Art, in 284 A.D. We are told that it consisted of three regiments modelled on the Roman legion; each of these bodies contained, on a peace footing, three thousand men, but in time of war could be indefinitely strengthened. Its object was to defend the coasts of Ireland and the country generally, throwing its weight upon the side of any prince who happened to be assailed by foreign foes. During the six months of winter, its members were quartered upon the population, but during the summer they had to forage for themselves, which they did by hunting and fishing. Thus they lived in the woods and on the open moors, hardening themselves for battle by their adventurous life. The sites of their enormous camp-fires were long pointed out under the name of the "Fenians' cooking-places".

It was not easy to become a member of this famous band. A candidate had to be not only an expert warrior, but a poet and a man of culture as well. He had practically to renounce his tribe; at any rate he made oath that he would neither avenge any of his relatives nor be avenged by them. He put himself under bonds never to refuse hospitality to anyone who asked, never to turn his back in battle, never to insult any woman, and not to accept a dowry with his wife. In addition to all this, he had to pass successfully through the most stringent physical tests. Indeed, as these have come down to us, magnified by the perfervid Celtic imagination, they are of an altogether marvellous and impossible character. An aspirant to the Fianna Eirinn, we are told, had first to stand up to his knees in a pit dug for him, his only arms being his shield and a hazel wand, while nine warriors, each with a spear, standing within the distance of nine ridges of land, all hurled their weapons at him at once; if he failed to ward them all off, he was rejected. Should he succeed in this first test, he was given the distance of one tree-length's start, and chased through a forest by armed men; if any of them came up to him and wounded him, he could not belong to the Fenians. If he escaped unhurt, but had unloosed a single lock of his braided hair, or had broken a single branch in his flight, or if, at the end of the run, his weapons trembled in his hands, he was refused. As, besides these tests, he was obliged to jump over a branch as high as his forehead, and stoop under one as low as his knee, while running at full speed, and to pluck a thorn out of his heel without hindrance to his flight, it is clear that even the rank and file of the Fenians must have been quite exceptional athletes.1

But it is time to pass on to a more detailed description of these champions.2 They are a goodly company, not less heroic than the mighty men of Ulster. First comes Finn himself, not the strongest in body of the Fenians, but the truest, wisest, and kindest, gentle to women, generous to men, and trusted by all. If he could help it, he would never let anyone be in trouble or poverty. "If the dead leaves of the forest had been gold, and the white foam of the water silver, Finn would have given it all away."

Finn had two sons, Fergus and his more famous brother Ossian1. Fergus of the sweet speech was the Fenian's bard, and, also, because of his honeyed words, their diplomatist and ambassador. Yet, by the irony of fate, it is to Ossian, who is not mentioned as a poet in the earliest texts, that the poems concerning the Fenians which are current in Scotland under the name of "Ossianic Ballads" are attributed. Ossian's mother was Sadb, a daughter of Bodb the Red. A rival goddess changed her into a deer--which explains how Ossian got his name, which means "fawn". With such advantages of birth, naturally he was speedy enough to run down a red deer hind and catch her by the ear, though far less swift-footed than his cousin Caoilte2, the "Thin Man". Neither was he so strong as his own son Oscar, the mightiest of all the Fenians, yet, in his youth, so clumsy that the rest of the band refused to take him with them on their warlike expeditions. They changed their minds, however, when, one day, he followed them unawares, found them giving way before an enemy, and, rushing to their help, armed only with a great log of wood which lay handy on the ground, turned the fortunes of the fight.

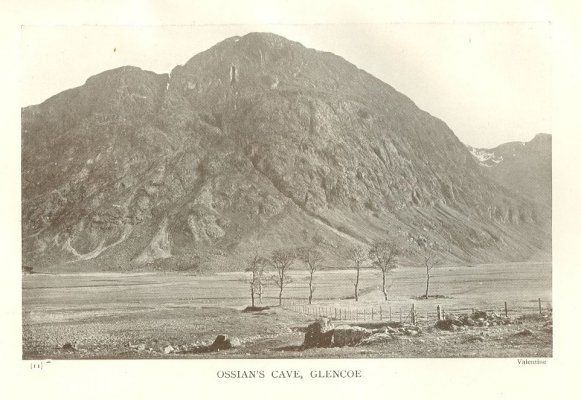

OSSIAN'S CAVE, GLENCOE

After this, Oscar was hailed the best warrior of all the Fianna; he was given command of a battalion, and its banner, called the "Terrible Broom", was regarded as the centre of every battle, for it was never known to retreat a foot. Other prominent Fenians were Goll1, son of Morna, at first Finn's enemy but afterwards his follower, a man skilled alike in war and learning. Even though he was one-eyed, we are told that he was much loved by women, but not so much as Finn's cousin, Diarmait O'Duibhne2, whose fatal beauty ensnared even Finn's betrothed bride, Grainne3. Their comic character was Conan, who is represented as an old, bald, vain, irritable man, as great a braggart as ancient Pistol and as foul-mouthed as Thersites, and yet, after he had once been shamed into activity, a true man of his hands. These are the prime Fenian heroes, the chief actors in its stories.

The Fenian epic begins, before the birth of its hero, with the struggle of two rival clans, each of whom claimed to be the real and only Fianna Eirinn. They were called the Clann Morna, of which Goll mac Morna was head, and the Clann Baoisgne4, commanded by Finn's father, Cumhal. A battle was fought at Cnucha5, in which Goll killed Cumhal, and the Clann Baoisgne was scattered. Cumhal's wife, however, bore a posthumous son, who was brought up among the Slieve Bloom Mountains secretly, for fear his father's enemies should find and kill him. The boy, who was at first called Deimne1, grew up to be an expert hurler, swimmer, runner, and hunter. Later, like Cuchulainn, and indeed many modern savages, he took a second, more personal name. Those who saw him asked who was the "fair" youth. He accepted the omen, and called himself Deimne Finn.

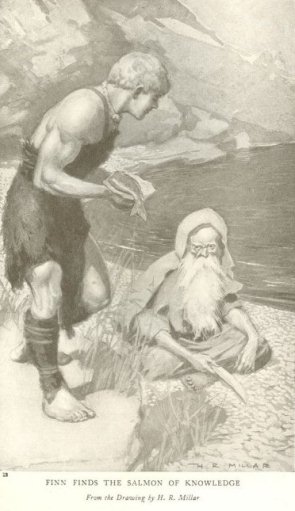

At length, he wandered to the banks of the Boyne, where he found a soothsayer called Finn the Seer living beside a deep pool near Slane, named "Fec's Pool", in hope of catching one of the "salmons of knowledge", and, by eating it, obtaining universal wisdom. He had been there seven years without result, though success had been prophesied to one named "Finn". When the wandering son of Cumhal appeared, Finn the Seer engaged him as his servant. Shortly afterwards, he caught the coveted fish, and handed it over to our Finn to cook, warning him to eat no portion of it. "Have you eaten any of it?" he asked the boy, as he brought it up ready boiled. "No indeed," replied Finn; "but, while I was cooking it, a blister rose upon the skin, and, laying my thumb down upon the blister, I scalded it, and so I put it into my mouth to ease the pain." The man was perplexed. "You told me your name was Deimne," he said; "but have you any other name?" "Yes, I am also called Finn." "It is enough," replied his disappointed master." Eat the salmon yourself, for you must be the one of whom the prophecy told." Finn ate the "salmon of knowledge", and thereafter he had only to put his thumb under his tooth, as he had done when he scalded it, to receive fore-knowledge and magic counsel.1

Thus armed, Finn was more than a match for the Clann Morna. Curious legends tell how he discovered himself to his father's old followers, confounded his enemies with his magic, and turned them into faithful servants.2 Even Goll of the Blows had to submit to his sway.

Gradually he welded the two opposing clans into one Fianna, over which he ruled, taking tribute from the kings of Ireland, warring against the Fomorian "Lochlannach", destroying every kind of giant, serpent, or monster that infested the land, and at last carrying his mythical conquests over all Europe.

Out of the numberless stories of the Fenian exploits it is hard to choose examples. All are heroic, romantic, wild, fantastic. In many of them the Tuatha Dé Danann play prominent parts. One such story connects itself with an earlier mythological episode already related. The reader will remember3 how, when the Dagda gave up the kingship of the immortals, five aspirants appeared to claim it; how of these five--Angus, Mider, Lêr, Ilbhreach son of Manannán, and Bodb the Red--the latter was chosen; how Lêr refused to acknowledge him, but was reconciled later; how Mider, equally rebellious, fled to "desert country round Mount Leinster" in County Carlow; and how a yearly war was waged upon him and his people by the rest of the gods to bring them to subjection. This war was still raging in the time of Finn, and Mider was not too proud to seek his help. One day that Finn was hunting in Donegal, with Ossian, Oscar, Caoilte, and Diarmait, their hounds roused a beautiful fawn, which, although at every moment apparently nearly overtaken, led them in full chase as far as Mount Leinster. Here it suddenly disappeared into a cleft in the hillside. Heavy snow, "making the forest's branches as it were a withe-twist", now fell, forcing the Fenians to seek for some shelter, and they therefore explored the place into which the fawn had vanished. It led to a splendid sídhe in the hollow of the hill. Entering it, they were greeted by a beautiful goddess-maiden, who told them that it was she, Mider's daughter, who had been the fawn, and that she had taken that shape purposely to lead them there, in the hope of getting their help against the army that was coming to attack the sídh. Finn asked who the assailants would be, and was told that they were Bodb the Red with his seven sons, Angus "Son of the Young" with his seven sons, Lêr of Sídh Fionnechaidh with his twenty-seven sons, and Fionnbharr of Sídh Meadha with his seventeen sons, as well as numberless gods of lesser fame drawn from sídhe not only over all Ireland, but from Scotland and the islands as well. Finn promised his aid, and, with the twilight of that same day, the attacking forces appeared, and made their annual assault. They were beaten off, after a battle that lasted all night, with the loss of "ten men, ten score, and ten hundred". Finn, Oscar, and Diarmait, as well as most of Mider's many sons, were sorely wounded, but the leech Labhra healed all their wounds.1

Sooth to say, the Fenians did not always require the excuse of fairy alliance to start them making war on the race of the hills. One of the so-called "Ossianic ballads" is entitled "The Chase of the Enchanted Pigs of Angus of the Brugh2". This Angus is, of course, the "Son of the Young", and the Brugh that famous sídh beside the Boyne out of which he cheated his father, the Dagda. After the friendly manner of gods towards heroes, he invited Finn and a picked thousand of his followers to a banquet at the Brugh. They came to it in their finest clothes, "goblets went from hand to hand, and waiters were kept in motion". At last conversation fell upon the comparative merits of the pleasures of the table and of the chase, Angus stoutly contending that "the gods' life of perpetual feasting" was better than all the Fenian huntings, and Finn as stoutly denying it. Finn boasted of his hounds, and Angus said that the best of them could not kill one of his pigs. Finn angrily replied that his two hounds, Bran3 and Sgeolan4, would kill any pig that trod on dry land. Angus answered that he could show Finn a pig that none of his hounds or huntsmen could catch or kill. Here were the makings of a pretty quarrel among such inflammable creatures as gods and heroes, but the steward of the feast interposed and sent everyone to bed. The next morning, Finn left the Brugh, for he did not want to fight all Angus's fairies with his handful of a thousand men. A year passed before he heard more of it; then came a messenger from Angus, reminding Finn of his promise to pit his men and hounds against Angus's pigs. The Fenians seated themselves on the tops of the hills, each with his favourite hound in leash, and they had not been there long before there appeared on the eastern plain a hundred and one such pigs as no Fenian had ever seen before. Each was as tall as a deer, and blacker than a smith's coals, having hair like a thicket and bristles like ships' masts. Yet such was the prowess of the Fenians that they killed them all, though each of the pigs slew ten men and many hounds. Then Angus complained that the Fenians had murdered his son and many others of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who, indeed, were none other than the pigs whose forms they had taken. There were mighty recriminations on both sides, and, in the end, the enraged Fenians prepared to attack the Brugh on the Boyne. Then only did Angus begin to yield, and, by the advice of Ossian, Finn made peace with him and his fairy folk.

Such are specimens of the tales which go to make up the Fenian cycle of sagas. Hunting is the most prominent feature of them, for the Fenians were essentially a race of mighty hunters. But the creatures of their chase were not always flesh and blood. Enchanters who wished the Fenians ill could always lure them into danger by taking the shape of boar or deer, and many a story begins with an innocent chase and ends with a murderous battle. But out of such struggles the Fenians always emerge successfully, as Ossian is represented proudly boasting, "through truthfulness and the might of their hands".

The most famous chase of all is, however, not that of deer or boar, but of a woman and a man, Finn's betrothed wife and his nephew Diarmait.1 Ever fortunate in war, the Fenian leader found disaster in his love. Wishing for a wife in his old age, he sent to seek Grainne, the daughter of Cormac, the High-King of Ireland. Both King Cormac and his daughter consented, and Finn's ambassadors returned with an invitation to the suitor to come in a fortnight's time to claim his bride. He arrived with his picked band, and was received in state in the great banqueting-hall of Tara. There they feasted, and there Grainne, the king's daughter, casting her eyes over the assembled Fenian heroes, saw Diarmait O'Duibhne.

This Fenian Adonis had a beauty-spot upon his cheek which no woman could see without falling instantly in love with him. Grainne, for all her royal birth, was no exception to this rule. She asked a druid to point her out the principal guests. The druid told her all their names and exploits. Then she called for a jewelled drinking-horn, and, filling it with a drugged wine, sent it round to each in turn, except to Diarmait. None could be so discourteous as to refuse wine from the hand of a princess. All drank, and fell into deep sleep.

Then, rising, she came to Diarmait, told him her passion for him, and asked for its return. "I will not love the betrothed of my chief," he replied, "and, even if I wished, I dare not." And he praised Finn's virtues, and decried his own fame. But Grainne merely answered that she put him under geasa (bonds which no hero could refuse to redeem) to flee with her; and at once went back to her chair before the rest of the company awoke from their slumber.

After the feast, Diarmait went round to his comrades, one by one, and told them of Grainne's love for him, and of the geasa she had placed upon him to take her from Tara. He asked each of them what he ought to do. All answered that no hero could break a geis put upon him by a woman. He even asked Finn, concealing Grainne's name, and Finn gave him the same counsel as the others. That night, the lovers fled from Tara to the ford of the Shannon at Athlone, crossed it, and came to a place called the "Wood of the Two Tents", where Diarmait wove a hut of branches for Grainne to shelter in.

Meanwhile Finn had discovered their flight, and his rage knew no bounds. He sent his trackers, the Clann Neamhuain1, to follow them. They tracked them to the wood, and one of them climbed a tree, and, looking down, saw the hut, with a strong seven-doored fence built round it, and Diarmait and Grainne inside. When the news came to the Fenians, they were sorry, for their sympathies were with Diarmait and not with Finn. They tried to warn him, but he took no heed; for he had determined to fight and not to flee. Indeed, when Finn himself came to the fence, and called over it to Diarmait, asking if he and Grainne were within, he replied that they were, but that none should enter unless he gave permission.

So Diarmait, like Cuchulainn in the war of Ulster against Ireland, found himself matched single-handed against a host. But, also like Cuchulainn, he had a divine helper. The favourite of the Tuatha Dé Danann, he had been the pupil of Manannán son of Lêr in the "Land of Promise", and had been fostered by Angus of the Brugh. Manannán had given him his two spears, the "Red Javelin" and the "Yellow Javelin", and his two swords, the "Great Fury" and the "Little Fury". And now Angus came to look for his foster-son, and brought with him the magic mantle of invisibility used by the gods. He advised Diarmait and Grainne to come out wrapped in the cloak, and thus rendered invisible. Diarmait still refused to flee, but asked Angus to protect Grainne. Wrapping the magic mantle round her, the god led the princess away unseen by any of the Fenians.

By this time, Finn had posted men outside all the seven doors in the fence. Diarmait went to each of them in turn. At the first, were Ossian and Oscar with the Clann Baoisgne. They offered him their protection. At the second, were Caoilte and the Clann Ronan, who said they would fight to the death for him. At the third, were Conan and the Clann Morna, also his friends. At the fourth, stood Cuan with the Fenians of Munster, Diarmait's native province. At the fifth, were the Ulster Fenians, who also promised him protection against Finn. But at the sixth, were the Clann Neamhuain, who hated him; and at the seventh, was Finn himself.

"It is by your door that I will pass out, O Finn," cried Diarmait. Finn charged his men to surround Diarmait as he came out, and kill him. But he leaped the fence, passing clean over their heads, and fled away so swiftly that they could not follow him. He never halted till he reached the place to which he knew Angus had taken Grainne. The friendly god left them with a little sage advice: never to hide in a tree with only one trunk; never to rest in a cave with only one entrance; never to land on an island with only one channel of approach; not to eat their supper where they had cooked it, nor to sleep where they had supped, and, where they had slept once, never to sleep again. With these Red-Indian-like tactics, it was some time before Finn discovered them.

However, he found out at last where they were, and sent champions with venomous hounds to take or kill them. But Diarmait conquered all who were sent against him.

Yet still Finn pursued, until Diarmait, as a last hope of escape, took refuge under a magic quicken-tree1, which bore scarlet fruit, the ambrosia of the gods. It had grown from a single berry dropped by one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who, when they found that they had carelessly endowed mortals with celestial and immortal food, had sent a huge, one-eyed Fomor called Sharvan the Surly to guard it, so that no man might eat of its fruit. All day, this Fomor sat at the foot of the tree, and, all night, he slept among its branches, and so terrible was his appearance that neither the Fenians nor any other people dared to come within several miles of him.

But Diarmait was willing to brave the Fomor in the hope of getting a safe hiding-place for Grainne. He came boldly up to him, and asked leave to camp and hunt in his neighbourhood. The Fomor told him surlily that he might camp and hunt where he pleased, so long as he refrained from taking any of the scarlet berries. So Diarmait built a hut near a spring; and he and Grainne lived there, killing the wild animals for food.

But, unhappily, Grainne conceived so strong a desire to eat the quicken berries that she felt that she must die unless her wish could be gratified. At first she tried to hide this longing, but in the end she was forced to tell her companion. Diarmait had no desire to quarrel with the Fomor; so he went to him and told the plight that Grainne was in, and asked for a handful of the berries as a gift.

But the Fomor merely answered: "I swear to you that if nothing would save the princess and her unborn child except my berries, and if she were the last woman upon the earth, she should not have any of them." Whereupon Diarmait fought the Fomor, and, after much trouble, killed him.

It was reported to Finn that the guardian of the magic quicken-tree lived no longer, and he guessed that Diarmait must have killed him; so he came down to the place with seven battalions of the Fenians to look for him. By this time, Diarmait had abandoned his own hut and taken possession of that built by the Fomor among the branches of the magic quicken. He was sitting in it with Grainne when Finn and his men came and camped at the foot of the tree, to wait till the heat of noon had passed before beginning their search.

To beguile the time, Finn called for his chess-board and challenged his son Ossian to a game. They played until Ossian had only one more move.

"One move would make you a winner," said Finn to him, "but I challenge you and all the Fenians to guess it."

Only Diarmait, who had been looking down through the branches upon the players, knew the move. He could not resist dropping a berry on to the board, so deftly that it hit the very chessman which Ossian ought to move in order to win. Ossian took the hint, moved it, and won. A second and a third game were played; and in each case the same thing happened. Then Finn felt sure that the berries that had prompted Ossian must have been thrown by Diarmait.

He called out, asking Diarmait if he were there, and the Fenian hero, who never spoke an untruth, answered that he was. So the quicken-tree was surrounded by armed men, just as the fenced hut in the woods had been. But, again, things happened in the same way; for Angus of the Brugh took away Grainne wrapped in the invisible magic cloak, while Diarmait, walking to the end of a thick branch, cleared the circle of Fenians at a bound, and escaped untouched.

This was the end of the famous "Pursuit"; for Angus came as ambassador to Finn, urging him to become reconciled to the fugitives, and all the best of the Fenians begged Finn to consent. So Diarmait and Grainne were allowed to return in peace.

But Finn never really forgave, and, soon after, he urged Diarmait to go out to the chase of the wild boar of Benn Gulban1. Diarmait killed the boar without getting any hurt; for, like the Greek Achilles, he was invulnerable, save in his heel alone. Finn, who knew this, told him to measure out the length of the skin with his bare feet. Diarmait did so. Then Finn, declaring that he had measured it wrongly, ordered him to tread it again in the opposite direction. This was against the lie of the bristles; and one of them pierced Diarmait's heel, and inflicted a poisoned and mortal wound.

This "Pursuit of Diarmait and Grainne", which has been told at such length, marks in some degree the climax of the Fenian power, after which it began to decline towards its end. The friends of Diarmait never forgave the treachery with which Finn had compassed his death. The ever-slumbering rivalry between Goll and his Clann Morna and Finn and his Clann Baoisgne began to show itself as open enmity. Quarrels arose, too, between the Fenians and the High-Kings of Ireland, which culminated at last in the annihilation of the Fianna at the battle of Gabhra1.

This is said to have been fought in A.D. 284. Finn himself had perished a year before it, in a skirmish with rebellious Fenians at the Ford of Brea on the Boyne. King Cormac the Magnificent, Grainne's father, was also dead. It was between Finn's grandson Oscar and Cormac's son Cairbré that war broke out. This mythical battle was as fiercely waged as that of Arthur's last fight at Camlan. Oscar slew Cairbré, and was slain by him. Almost all the Fenians fell, as well as all Cairbré's forces.

Only two of the greater Fenian figures survived. One was Caoilte, whose swiftness of foot saved him at the end when all was lost. The famous story, called the "Dialogue of the Elders", represents him discoursing to St. Patrick, centuries after, of the Fenians' wonderful deeds. Having lost his friends of the heroic age, he is said to have cast in his lot with the Tuatha Dé Danann. He fought in a battle, with Ilbhreach son of Manannán, against Lêr himself, and killed the ancient sea-god with his own hand.2 The tale represents him taking possession of Lêr's fairy palace of Sídh Fionnechaidh, after which we know no more of him, except that he has taken rank in the minds of the Irish peasantry as one of, and a ruler among, the Sídhe.

The other was Ossian, who did not fight at Gabhra, for, long before, he had taken the great journey which most heroes of mythology take, to that bourne from which no ordinary mortal ever returns. Like Cuchulainn, it was upon the invitation of a goddess that he went. The Fenians were hunting near Lake Killarney when a lady of more than human beauty came to them, and told them that her name was Niamh1, daughter of the Son of the Sea. The Gaelic poet, Michael Comyn, who, in the eighteenth century, rewove the ancient story into his own words,2 describes her in just the same way as one of the old bards would have done:

"A royal crown was on her head;

And a brown mantle of precious silk,

Spangled with stars of red gold,

Covering her shoes down to the grass.

"A gold ring was hanging down

From each yellow curl of her golden hair;

Her eyes, blue, clear, and cloudless,

Like a dew-drop on the top of the grass.

"Redder were her cheeks than the rose,

Fairer was her visage than the swan upon the wave,

And more sweet was the taste of her balsam lips

Than honey mingled thro' red wine.

"A garment, wide, long, and smooth

Covered the white steed,

There was a comely saddle of red gold,

And her right hand held a bridle with a golden bit.

"Four shoes well-shaped were under him,

Of the yellow gold of the purest quality;

A silver wreath was on the back of his head,

And there was not in the world a steed better."

Such was Niamh of the Golden Hair, Manannán's daughter; and it is small wonder that, when she chose Ossian from among the sons of men to be her lover, all Finn's supplications could not keep him. He mounted behind her on her fairy horse, and they rode across the land to the sea-shore, and then over the tops of the waves. As they went, she described the country of the gods to him in just the same terms as Manannán himself had pictured it to Bran, son of Febal, as Mider had painted it to Etain, and as everyone that went there limned it to those that stayed at home on earth.

"It is the most delightful country to be found

Of greatest repute under the sun;

Trees drooping with fruit and blossom,

And foliage growing on the tops of boughs.

"Abundant, there, are honey and wine,

And everything that eye has beheld,

There will not come decline on thee with lapse of time.

Death or decay thou wilt not see."

As they went they saw wonders. Fairy palaces with bright sun-bowers and lime-white walls appeared on the surface of the sea. At one of these they halted, and Ossian, at Niamh's request, attacked a fierce Fomor who lived there, and set free a damsel of the Tuatha Dé Danann whom he kept imprisoned. He saw a hornless fawn leap from wave to wave, chased by one of those strange hounds of Celtic myth which are pure white, with red ears. At last they reached the "Land of the Young", and there Ossian dwelt with Niamh for three hundred years before he remembered Erin and the Fenians. Then a great wish came upon him to see his own country and his own people again, and Niamh gave him leave to go, and mounted him upon a fairy steed for the journey. One thing alone she made him swear--not to let his feet touch earthly soil. Ossian promised, and reached Ireland on the wings of the wind. But, like the children of Lêr at the end of their penance, he found all changed. He asked for Finn and the Fenians, and was told that they were the names of people who had lived long ago, and whose deeds were written of in old books. The Battle of Gabhra had been fought, and St. Patrick had come to Ireland, and made all things new. The very forms of men had altered; they seemed dwarfs compared with the giants of his day. Seeing three hundred of them trying in vain to raise a marble slab, he rode up to them in contemptuous kindness, and lifted it with one hand. But, as he did so, the golden saddle-girth broke with the strain, and he touched the earth with his feet. The fairy horse vanished, and Ossian rose from the ground, no longer divinely young and fair and strong, but a blind, gray-haired, withered old man.

A number of spirited ballads1 tell how Ossian, stranded in his old age upon earthly soil, unable to help himself or find his own food, is taken by St. Patrick into his house to be converted. The saint paints to him in the brightest colours the heaven which may be his own if he will but repent, and in the darkest the hell in which he tells him his old comrades now lie in anguish. Ossian replies to the saint's arguments, entreaties, and threats in language which is extraordinarily frank. He will not believe that heaven could be closed to the Fenians if they wished to enter it, or that God himself would not be proud to claim friendship with Finn. And if it be not so, what is the use to him of eternal life where there is no hunting, or wooing fair women, or listening to the songs and tales of bards? No, he will go to the Fenians, whether they sit at the feast or in the fire; and so he dies as he had lived.

201:1 The translations of Fenian stories are numerous. The reader will find many of them popularly retold in Lady Gregory's Gods and Fighting Men. Thence he may pass on to Mr. Standish Hayes O'Grady's Silva Gadelica; the Waifs and .Strays of Celtic Tradition, especially Vol. IV; Mr. J. G. Campbell's The Fians; as well as the volumes of the Revue Celtique and the Transactions of the Ossianic Society.

201:2 See O'Curry's translation in Appendix CXXVIII to his MS. Materials.

202:1 The story, found in the Book of the Dun Cow, appears in French in De Jubainville's Épopée Celtique.

203:1 This famous story is told in several MSS. of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. For translations see Dr. Whitley Stokes, Irische Texte, and Standish Hayes O'Grady, Transactions of the Ossianic Society, Vol. III.

203:2 In Gaelic spelling, Fionn mac Cumhail.

203:3 Pronounced Fēna.

204:1 O'Curry: MS. Materials, Lecture XIV, p. 303.

204:2 Pronounced Coul or Cooal.

205:1 Agalamh na Senórach. Under the title The Colloquy of the Ancients, there is an excellent translation of it, from the Book of Lismore, in Standish Hayes O'Grady 's Silva Gadelica.

205:2 O'Grady: Silva Gadelica.

205:3 Hibbert Lectures, p. 355.

207:1 See The Enumeration of Finn's Household, translated by O'Grady in Silva Gadelica.

207:2 For a good account, see J. G. Campbell's The Finns, pp. 10-80.

208:1 In more correct spelling, Oisin, and pronounced Usheen or Isheen.

208:2 Pronounced Kylta or Cweeltia.

209:1 Pronounced Gaul.

209:2 Pronounced Dermat O'Dyna.

209:3 Pronounced Grania.

209:4 Pronounced Baskin.

209:5 Now Castleknock, near Dublin.

210:1 Pronounced Demna.

211:1 This and other "boy-exploits" of Finn mac Cumhail are contained in a little tract written upon a fragment of the ninth century Psalter of Cashel. It is translated in Vol. IV of the Transactions of the Ossianic Society.

211:2 Campbell's Fians, p. 22.

211:3 See chap. XI--"The Gods in Exile".

213:1 From the Colloquy of the Ancients in O'Grady's Silva Gadelica.

213:2 It is translated in Vol. VI of the Transactions of the Ossianic Society.

213:3 Pronounced Brăn, not Brān.

213:4 Pronounced Skōlaun or Scolaing.

215:1 A fine translation of the Pursuit of Diarmait and Grainne has been published by S. H. O'Grady in Vol. III of the Transactions of the Ossianic Society.

216:1 Pronounced Navin or Nowin.

218:1 The mountain-ash, or rowan.

221:1 Now called Benbulben. It is near Sligo.

222:1 Pronounced Gavra.

222:2 See O'Grady's Silva Gadelica.

223:1 Pronounced Nee-av.

223:2 The Lay of Oisin in the Land of Youth, translated by Brian O'Looney for the Ossianic Society--Transactions, Vol. IV. A fine modem poem on the same subject is W. B. Yeats' Wanderings of Oisin.

226:1 See the Transactions of the Ossianic Society. They are generally called the Dialogues of Oisin and Patrick.