Celtic Myth and Legend Poetry and Romance

by Charles Squire

CHAPTER XX

THE VICTORIES OF LIGHT OVER DARKNESS

The powers of light were, however, by no means invariably successful in their struggles with the powers of darkness. Even Gwydion son of Dôn had to serve his apprenticeship to misfortune. As-sailing Caer Sidi--Hades1 under one of its many titles,--he was caught by Pwyll and Pryderi, and endured a long imprisonment.2 The sufferings he underwent made him a bard--an ancient Celtic idea which one can still see surviving in the popular tradition that whoever dares to spend a night alone either upon the chair of the Giant Idris (the summit of Cader Idris, in Merionethshire), or under the haunted Black Stone of Arddu, upon the Llanberis side of Snowdon, will be found in the morning either inspired or mad.3 How he escaped we are not told; but the episode does not seem to have quenched his ardour against the natural enemies of his kind.

Helped by his brother, Amaethon, god of agriculture, and his son, Lleu, he fought the Battle of Godeu, or "the Trees", an exploit which is not the least curious of Celtic myths. It is known also as the Battle of Achren, or Ochren, a name for Hades of unknown meaning, but appearing again in the remarkable Welsh poem which describes the "Spoiling of Annwn" by Arthur. The King of Achren was Arawn; and he was helped by Brân, who apparently had not then made his fatal journey to Ireland. The war was made to secure three boons for man--the dog, the deer, and the lapwing, all of them creatures for some reason sacred to the gods of the nether world.

Gwydion was this time not alone, as he apparently was when he made his first unfortunate reconnaissance of Hades. Besides his brother and his son, he had an army which he raised for the purpose. For a leader of Gwydion's magical attainments there was no need of standing troops. He could call battalions into being with a charm, and dismiss them when they were no longer needed. The name of the battle shows what he did on this occasion; and the bard Taliesin adds his testimony:

"I have been in the battle of Godeu, with Lieu and

Gwydion,

They changed the forms of the elementary trees and sedges".

In a poem devoted to it1 he describes in detail what happened. The trees and grasses, he tells us, hurried to the fight: the alders led the van, but the willows and the quickens came late, and the birch, though courageous, took long in arraying himself; the elm stood firm in the centre of the battle, and would not yield a foot; heaven and earth trembled before the advance of the oak-tree, that stout door-keeper against an enemy; the heroic holly and the hawthorn defended themselves with their spikes; the heather kept off the enemy on every side, and the broom was well to the front, but the fern was plundered, and the furze did not do well; the stout, lofty pine, the intruding pear-tree, the gloomy ash, the bashful chestnut-tree, the prosperous beech, the long-enduring poplar, the scarce plum-tree, the shelter-seeking privet and woodbine, the wild, foreign laburnum; "the bean, bearing in its shade an army of phantoms"; rose-bush, raspberry, ivy, cherry-tree, and medlar--all took their parts.

In the ranks of Hades there were equally strange fighters. We are told of a hundred-headed beast, carrying a formidable battalion under the root of its tongue and another in the back of its head; there was a gaping black toad with a hundred claws; and a crested snake of many colours, within whose flesh a hundred souls were tormented for their sins--in fact, it would need a Doré or a Dante to do justice to this weird battle between the arrayed magics of heaven and hell.

It was magic that decided its fate. There was a fighter in the ranks of Hades who could not be overcome unless his antagonist guessed his name--a peculiarity of the terrene gods, remarks Professor Rhys,1 which has been preserved in our popular fairy tales. Gwydion guessed the name, and sang these two verses:--

Sure-hoofed is my steed impelled by the spur;

The high sprigs of alder are on thy shield;

Brân art thou called, of the glittering

branches!

"Sure-hoofed is my steed in the day of battle:

The high sprigs of alder are on thy hand:

Brân . . . by the branch thou bearest

Has Amaethon the Good prevailed!"1

Thus the power of the dark gods was broken, and the sons of Dôn retained for the use of men the deer, the dog, and the lapwing, stolen from that underworld, whence all good gifts came.

It was always to obtain some practical benefit that the gods of light fought against the gods of darkness. The last and greatest of Gwydion's raids upon Hades was undertaken to procure--pork!2

Gwydion had heard that there had come to Dyfed some strange beasts, such as had never been seen before. They were called "pigs" or "swine", and Arawn, King of Annwn, had sent them as a gift to Pryderi son of Pwyll. They were small animals, and their flesh was said to be better than the flesh of oxen. He thought it would be a good thing to get them, either by force or fraud, from the dark powers. Mâth son of Mâthonwy, who ruled the children of Dôn from his Olympus of Caer Dathyl3, gave his consent, and Gwydion set off, with eleven others, to Pryderi's palace1. They disguised themselves as bards, so as to be received by Pryderi, and Gwydion, who was "the best teller of tales in the world", entertained the Prince of Dyfed and his court more than they had ever been entertained by any story-teller before. Then he asked Pryderi to grant him a boon--the animals which had come from Annwn. But Pryderi had pledged his word to Arawn that he would neither sell nor give away any of the new creatures until they had increased to double their number, and he told the disguised Gwydion so.

"Lord," said Gwydion, "I can set you free from your promise. Neither give me the swine at once, nor yet refuse them to me altogether, and to-morrow I will show you how."

He went to the lodging Pryderi had assigned him, and began to work his charms and illusions. Out of fungus he made twelve gilded shields, and twelve horses with gold harness, and twelve black grey-hounds with white breasts, each wearing a golden collar and leash. And these he showed to Pryderi.

"Lord," said he, "there is a release from the word you spoke last evening concerning the swine--that you may neither give them nor sell them. You may exchange them for something which is better. I will give you these twelve horses with their gold harness, and these twelve greyhounds with their gold collars and leashes, and these twelve gilded shields for them."

Pryderi took counsel with his men, and agreed to the bargain. So Gwydion and his followers took the swine and went away with them, hurrying as fast as they could, for Gwydion knew that the illusion would not last longer than a day. The memory of their journey was long kept up; every place where they rested between Dyfed and Caer Dathyl is remembered by a name connecting it with pigs. There is a Mochdrev ("Swine's Town") in each of the three counties of Cardiganshire, Montgomeryshire, and Denbighshire, and a Castell y Moch ("Swine's Castle") near Mochnant ("Swine's Brook"), which runs through part of the two latter counties. They shut up the pigs in safety, and then assembled all Mâth's army; for the horses and hounds and shields had returned to fungus, and Pryderi, who guessed Gwydion's part in it, was coming northward in hot haste.

There were two battles--one at Maenor Penardd, near Conway, and the other at Maenor Alun, now called Coed Helen, near Caernarvon. Beaten in both, Pryderi fell back upon Nant Call, about nine miles from Caernarvon. Here he was again defeated with great slaughter, and sent hostages, asking for peace and a safe retreat.

This was granted by Mâth; but, none the less, the army of the sons of Dôn insisted on following the retreating host, and harassing it. So Pryderi sent a complaint to Mâth, demanding that, if there must still be war, Gwydion, who had caused all the trouble, should fight with him in single combat.

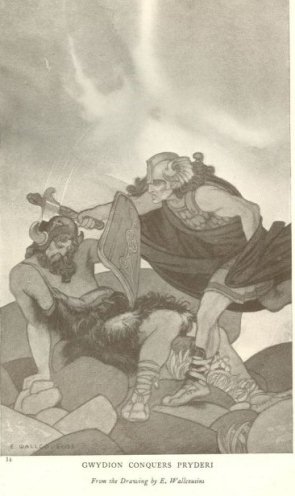

Gwydion agreed, and the champions of light and darkness met face to face. But Pryderi was the waning power, and he fell before the strength and magic of Gwydion. "And at Maen Tyriawc, above Melenryd, was he buried, and there is his grave", says the Mabinogi, though the ancient Welsh poem, called the "Verses of the Graves of the Warriors"1, assigns him a different resting-place.2

This decisive victory over Hades and its kings was the end of the struggle, until it was renewed, with still more complete success, by one greater than Gwydion--the invincible Arthur.

305:1 Or the Celtic Elysium, "a mythical country beneath the waves of the sea".

305:2 See the Spoiling of Annwn, quoted in chap. XXI--"The Mythological 'Coming of Arthur'".

305:3 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, pp. 250-251.

306:1 Book of Taliesin VIII, Vol. I, p. 276, of Skene. I have followed Skene's translation, with the especial exception of the curious line referring to the bean, so translated in D. W. Nash's Taliesin. If a correct rendering of the Welsh original, it offers an interesting parallel to certain superstitions of the Greeks concerning this vegetable.

307:1 Rhys: Hibbert Lectures, note to p. 245.

308:1 Lady Guest's translation in her notes to Kulhwch and Olwen.

308:2 The following episode is retold from Lady Guest's translation of the Mabinogi of Mâth, Son of Mathonwy.

308:3 Now called Pen y Gaer. It is on the summit of a hill half-way between Llanrwst and Conway, and about a mile from the station of Llanbedr.

309:1 Said to have been at Rhuddlan Teivi, which is, perhaps, Glan Teivy, near Cardigan Bridge.

311:1 Poem XIX in the Black Book of Caermarthen, Vol. I, p. 309, of Skene.

Where the waves beat against the land."

Index | Next: Chapter XXI. The Mythological

''Coming of Arthur''