|

|

History of Atlantis by Lewis Spence

Index | Chapter: 1 | 2 |3 | 4 |5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |9 | 10 |11 | 12 |13 | 14 |15 | 16

CHAPTER VIII.

THE KINGS OF ATLANTIS

IT is from the writings of Diodorus the Sicilian, as well as from those of Plato, that we are enabled to glean the little we know concerning the royal line of Atlantis. Plato, indeed, assures us that such a succession existed, but he leaves us in the dark concerning the names of any of its members, with the exception of the sons of Poseidon: Atlas, Gadir or Eumolus, Amphisus, Eudemon, Mnesus, Autochthonus, Elassipus, Mestor, Azaes and Diaprepus. Let us examine these first, and see what we can glean from them.

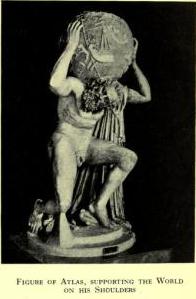

In other myths Atlas is alluded to as the son of lapetus and Clymene, and brother of Prometheus and Epimetheus, the Titans, along with whom he made war against Zeus. Defeated by the Hellenic Allfather, he was compelled to bear the skies upon his head and shoulders. According to Homer, he is, indeed, the bearer of the long columns which hold the heavens and earth asunder. Indeed, he is what students of Mexican mythology, following the late Professor Eduard Seler, would now call a "sky-supporter," one of these genii who uphold the roof of the world. The idea probably arose from the belief that Mount Atlas, in Africa, like other lofty mountains, actually upheld the skies. Other mythographers, as we have seen, represent Atlas as a wise astrologer, a monarch who first taught men the science of reading the stars. There was, of course, more than one Mount Atlas, and we find mountains similarly named in Mauretania, Arcadia and Caucasus. The Pleides, Hyades and Hesperides were his daughters.

Eumolus, or Eumolpus, otherwise known as Gadir, whose name is associated with Cadiz and the straits of Gibraltar, the ancient Fretum Gaditanum, was regarded as the founder of the Eleusinian mysteries, of which more hereafter. Of Amphisus, Eudemon and Mnesus, we find no mention in classical mythology. The name Autochthonus merely implies "aborigine," but it is to be remarked that it was usually applied by the Greeks to people of the ancient Pelasgian stock, whose story, says Mr. Walters in his Classical Dictionary, "may be paralleled from those of the Basques in Spain and the Celts of Wales." They were, indeed, the introducers of all culture to Greece. Elassipus, Mestor and Azaes are all equally unknown to classical tradition, and the same holds good of Diaprepus. We should remember, however, that Plato expressly states that these names had been Egyptianized from the Atlantean language by the priest of Sais, and subsequently Hellenised by Critias, so that there is little hope that they were transmitted in anything like their original form.

So far Plato. Diodorus tells us that Uranus was the first King of the Atlanteans. Uranus was the Greek god of the Sky, and father of lapetus the Titan, the Biblical Japhet, of Oceanus, the Cyclopes, and many other mythical figures, including the Giants. His most celebrated Atlantean children were Basilea (which simply means "queen") and Rhea or Pandora. Atlas, Saturn and Hesperus are also mentioned as his offspring. The Atlantides became the constellation of the Pleiades. A certain Jupiter not the god of that name later became King of the Atlanteans, displacing his father Saturn with the aid of the Titans.

It becomes clear that the mythical

history of Atlantis is in some manner associated with the

incidents of the war between the Gods and Titans, which bulks so

largely in Greek mythi-history and art. The story of the

Titanomachia, or divine war with the Titans, relates that Uranus

the first ruler of the world, cast his sons, Briareus, Cottys and

Gyes, the Hecatoncheires, or Hundred-handed, into Tartarus, along

with the Cyclopes, "the creatures with round or circular eyes,"

gigantic shepherds of Sicily. Gaea, his wife, indignant at this,

urged the Titans to rise against their father. They deposed him,

and raised Cronus to the throne. But Cronus, in turn, hurled the

Cyclopes back into Tartarus, and married his sister Rhea. Uranus

and Gaea had foretold that he would himself be deposed by his own

children, and as these were born he swallowed them, all but Zeus,

whom his mother concealed in a cave in Crete. When Zeus came to

manhood he gave his father a potion which caused him to disgorge

the children he had swallowed, and these turned against Cronus

and the ruling Titans. Gaea promised victory to Zeus if he would

deliver the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires from Tartarus. He did so,

and the Titans were overcome and themselves cast into

Tartarus.

It becomes clear that the mythical

history of Atlantis is in some manner associated with the

incidents of the war between the Gods and Titans, which bulks so

largely in Greek mythi-history and art. The story of the

Titanomachia, or divine war with the Titans, relates that Uranus

the first ruler of the world, cast his sons, Briareus, Cottys and

Gyes, the Hecatoncheires, or Hundred-handed, into Tartarus, along

with the Cyclopes, "the creatures with round or circular eyes,"

gigantic shepherds of Sicily. Gaea, his wife, indignant at this,

urged the Titans to rise against their father. They deposed him,

and raised Cronus to the throne. But Cronus, in turn, hurled the

Cyclopes back into Tartarus, and married his sister Rhea. Uranus

and Gaea had foretold that he would himself be deposed by his own

children, and as these were born he swallowed them, all but Zeus,

whom his mother concealed in a cave in Crete. When Zeus came to

manhood he gave his father a potion which caused him to disgorge

the children he had swallowed, and these turned against Cronus

and the ruling Titans. Gaea promised victory to Zeus if he would

deliver the Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires from Tartarus. He did so,

and the Titans were overcome and themselves cast into

Tartarus.

We find, then, the self-same personages connected with the war of the Gods and Titans as with Atlantis. Indeed it is clear that Diodorus actually applies the story and personnel of the war of the Gods and Titans to the history of Atlantis. On what grounds did he do so? He could only have done so because of an existing tradition. He certainly did not invent the tale of the Titanic War, which was in circulation centuries before his time. It seems reasonable to suppose, then, that a tradition actually existed of a great war in the Atlantic Ocean. The Gods, thought the Greeks, had their origin in the West. Thence came the mysteries and all culture. The Cyclopes and Titans are likewise connected with the West, the former with Sicily and the Mediterranean isles, the latter with other islands. Pomponius Mela states that Albion, the Titan, son of Poseidon, and the original tutelary god of Britain, was a brother of Atlas, and assisted him with Iberius, god of Ireland, to contest the Western passage of Hercules. Albion is that Alba from which Scotland takes her ancient name of Albany. There was thus a distinct race of Titans connected with the Atlantic, and if Albion and Iberius can be identified with the British Isles, it is only reasonable to assume that Atlas was also once the tutelary divinity of a western land in the ocean with which myth persistently connects his name.

The histories of all peoples commence with a dynasty of god-kings, only shading later into "real" history as time proceeds. The Greek and Roman dynasties, the Egyptian, the Babylonian, the Mexican and Central American annals, all began with traditional notions of the lives and deeds of heaven-descended monarchs. Nor is our own Britain any less pious in her royal genealogies. I have seen in a roadside inn a modern illustrated genealogy drawing the descent of King George V from Adam arid the early "mythical" Scottish Kings, and have we not our Lears and Arthurs? What is myth in its historical form? Is it not merely traditional history handed down before the age of writing? Mena, the first King of the First Dynasty of Egypt, was regarded as mythical until a reference to him was discovered upon a contemporary tomb. Troy was regarded as a dream of "Homer" before Schliemann discovered it. Chedarlaomer was also considered as legendary before inscriptions bearing his name were found. A hundred instances of great names recovered from myth could be adduced. Is there any good reason, then, for denying that it is quite probable that the names of the Kings of Atlantis as given by Plato and Diodorus may not at one time have belonged to veritable historical persons?

As I have said, we labour under the disability of having the names of the Kings of Atlantis in a Greek form only. Nor have we the least chronological clue to their period. That they ruled over Atlantis in its Stone Age period is as unlikely as that Lear or Arthur represent the Neolithic Age in Britian. They are called "the first Kings " of Atlantis, and no very extraordinary antiquity is claimed for them prior to the cataclysm.

Everything points to the probability that, just as Atlantis experienced several cataclysmic visitations, so did she experience more than one revolution of cultural and political change. The Aurignacian art which seems to have proceeded from her, exhibits certain signs of cultivation during many centuries long before it reached its European seat, and the Azilian decadence in art, coupled with a progress in things material, indicates another revolution of the wheel of human affairs in Atlantis. The Aurignacian remains, as has been said, seem to point to the prior existence of a very great civilisation upon Atlantis at some time prior to the end of the Pleistocene era.

If this hypothesis be examined without heat or bias, it will be recognised as by no means so wildly improbable as it at first appears.

The Aurignacian colonisation of Europe occurred at the close of the Great Ice Age, or about 25,000 years ago. In Europe, the main ice-cap stretched from Cape North in Norway to the North of France, covering a space coincident with present-day Prussia. Here and there, in the more southerly countries, it manifested itself where greater or less mountain ranges reared their heads, but its phenomena were less imposing in these regions, owing to the smaller size of the mountains, and their situation on a warmer isothermal line. North Africa shows little or no glaciation, and it is, therefore, most unlikely that Atlantis which was much in the same latitude, and which was a maritime country at that, would have experienced any great degree of glaciation, or indeed would during the Ice Age have possessed a climate any more rigorous than that of, say, the North of Scotland to-day.

If this be admitted, and if we also admit the presence upon Atlantis of a race of men the Cro-Magnon of undoubted superiority in culture and brain-power (a conclusion at which we are justified in arriving by virtue of the size of the Cro-Magnon brain-case, as well as from the remains of Aurignacian art) there is nothing very outrageous in the assumption that at a period when Europe was either buried beneath the Pleistocene ice, or powerfully affected in its southerly regions by local glaciations, Atlantis, comparatively free from those conditions, and enjoying a climate of reasonably temperate character, should not have nursed a civilisation which at a subsequent epoch was destroyed by a series of cataclysms of a volcanic or seismic nature.

We find that Plato's divine race, the sons of Poseidon, were descended on the female side from an autochthonous or aboriginal strain. These we may regard as the Azilians, for certain considerations seem to render it probable that the great civiliser Poseidon (if we regard him as a human figure), settled in Atlantis some centuries before the coming of the Azilians to Europe, or, roughly, about a thousand years before the submergence of Atlantis. By that time the ancient Aurignacian culture in the island-continent must have been almost totally extinct. That the race itself was not, seems to be implied by the statement in the myth of the war with the Titans regarding the Cyclopes. These Cyclopes were a tall, round-eyed race, clothed in skins, and dwelling in caves. Their description, indeed, answers almost exactly to that of the Cro-Magnons, who must have been the degenerate aborigines of Atlantis. The Cro-Magnon skull was large, the cheek-bones high, the eye-orbits immense, and the whole physique powerful. And we know that the Cro-Magnons, like the Cyclopes, dressed in skins and dwelt in caves.

We find, then, that Poseidon, the culture-bringer, arriving in Atlantis some centuries prior to its final submergence, allied himself with the remnants of the Cro-Magnon aborigines and gave their dying culture a more modern tendency, precisely as did Quetzalcoatl in Mexico. Indeed the myths of Poseidon and Quetzalcoatl are practically identical. In Atlantis in America I have adduced proof that the personalities of Atlas and Quetzalcoatl are the same (pp. 199 ff.) and this applies with equal force to Poseidon, the father of Atlas, who possesses the same attributes of the culture-hero . We know that Quetzalcoatl came to Mexico from some locality in the Atlantic. But whence did Poseidon come?

Poseidon, I believe, was the leader of the Azilian or proto-Azilian band of invaders who conquered Atlantis, and colonised it some centuries prior to making their great raid on Europe. He is usually described as a god of "Pelasgian" origin. Now this name Pelasgian is usually employed to denote a race who colonised Greece at an early period, and who built immense structures of solid stone. They were, indeed, the Mykenean race, the bringers of the mysteries of the Cabiri to Greece, a people of Iberian stock. The Azilians, as we have seen, were proto-Iberians. We have, therefore, good grounds for the statement that Poseidon was the leader or priest-king of the Azilian invaders of Atlantis. That the whole Iberian race is distantly of North African origin scarcely admits of doubt, and it seems probable that Poseidon, "god" of the Mediterranean Sea, must have led his people from the Atlas region of North Africa to Atlantis, whence, some centuries later, they were to invade both Europe and their original home.

If these surely not very dubious conclusions be granted as reasonable, we have the material for a sketch, faint and with many lacunae, perhaps, of historical events in Atlantis, from the period ante-dating the Cro-Magnon invasion of Europe to the final submergence of the island-continent.

We must, in the first place, imagine Atlantis, an island nearly the size of Australia, as the seat of a great prehistoric civilisation of very considerable pretensions. A race of fine physique such physique, indeed, as the world has not since beheld inhabits it. By the aid of flint tools, as well as native genius, it has succeeded under the happy conditions of an environment unhampered by the Pleistocene ice, in developing an admittedly higher type of artistic effort at a period about 23,000 years or more before the Christian era. It celebrates religious ceremonies in large caves decorated with elaborate paintings of its animal and semi-human gods, and further embellishes these with bas-reliefs and statuettes of idols. Its public life circulates and flourishes around these cave-temples, outside of which it probably erects huts and small houses of stone or clay. It develops, as we have seen, social classes, the prototypes of these of the present day.

Then, some 22,000 years ago, its island-home is visited by a severe seismic cataclysm beneath the fury of which portions of the area are hurled into the sea. Terrified, large masses of its inhabitants make for the European continent across the land-bridge. They have previously been averse from settling in the continental area because of the notoriously cold and uncongenial conditions obtaining there, but with the gradual disappearance of the ice these have been somewhat mitigated, and they now experience little difference between them and those of their native home. Those who remain carry on the ancient culture, which the colonists allow to degenerate somewhat.

About 14,000 B.C. a second cataclysm occurs, and this compels large numbers of the Atlanteans (Magdalenians) to fly to the European area. They carry with them an art which, because it has remained in the ancient home, considerably surpasses in technique and detail the degenerate Cro-Magnon art, but they have later to face a return of the glacial conditions in Europe.

Then, seemingly about 10,500 B.C., " Poseidon" and his Azilian Proto-Iberians invade Atlantis from the North African region.

It is from this point that we obtain a hold upon the realities of Atlantean history. Poseidon must have been an early culture-hero, similar to those whom we find connected with the Polynesian and Mexican migration myths. Indeed, he behaves in Atlantis precisely as these do in their own spheres. Now it is most unlikely that Plato could have personally manufactured a tale which fits in so precisely with the circumstances of other and later culture-hero tales. It is in such cases that Folklore is of assistance to history.

Poseidon takes over the lordship of the island of Atlantis. He marries a native woman. He excavates large canals, and builds "a temple upon a hill. He rears a progeny of twins, who subsequently rule the island and the surrounding isles, found a special caste and also a religious system of their own, based on ancestor-worship.

These circumstances are almost paralleled by the legend of Hotu Matua, the culture-hero of Easter Island, in the Pacific, a locality which, like the Canaries, is obviously a remnant of a great sunken oceanic continent.

Marooned on Easter Island with a band of followers, Hotu Motua set himself the task of reconstructing society there. He reared immense structures in stone, walls, rude shrines and statues. By a system of ingenious taboos he secured and perpetuated the religion of his Polynesian fathers.

Other myths exhibit similar circumstances. The Creek Indians say that Esaugetuh Emissee, "the Master of Breath," came to the island Nunne Chaha, which lay in the primeval Waste of Waters, and built a house there. He built a great encircling wall, and directed the waters into channels. What is this but the story of Poseidon in Atlantis?

Manibozho, the great god of the Algonquin Indians, is said to have "carved the land and sea to his liking," just as the Huron deity Tawiscara "guided the waters into smooth channels." The Peruvian god Pariacaca arrived, as Poseidon had done, in a hilly country. But the people reviled him, and he sent a great flood upon them, so that their village was destroyed. Meeting a beautiful maiden, Cheque Suso, who was weeping bitterly, he inquired the cause of her grief, and she informed him that the maize crop was dying for lack of water. He assured her that he would revive the maize if she would bestow her affections on him, and when she consented to his suit, he irrigated the land by canals. Eventually he turned his wife into a statue.

Another Peruvian myth recounts that the god Thonapa, angered at the people of Yamquisapa in the province of Alla-suyu because they were so bent on pleasure, drowned their city in a great lake. The people of this region worshipped a statue in the form of a woman which stood on the summit of the hill Cachapucara, Thonapa destroyed both hill and image and disappeared into the sea.

We find in these myths most of the elements which go to make up the story of Poseidon in Atlantis, the sacred hill, the making of zones of land and water, the god marrying the native maiden, the disastrous flood. This is what is known to mythologists as "the test of recurrence." If one part of a myth be found in one part of the world, and another overlapping section of it in another part, it is demonstrably clear that these are floating fragments of a once homogeneous myth, and that the parts of these which do not correspond are supplementary to each other, linked together by those which do correspond.

Now, no such myth, so far as I am aware, was current concerning the Mediterranean islands, or could have been available to Plato. How, then, was it possible for him to make use of material which undoubtedly existed elsewhere, but of which he could not have been aware had not a general tradition of the circumstances of Atlantean history survived, disseminated on one hand to Europe, and Egypt, and on the other to America? Traditions, we know, survive for countless centuries, and there is nothing extravagant in the supposition that that which referred to Atlantis slowly but surely became known to peoples on both continents.

In the account of Diodorus it is clear that Uranus stands for Poseidon as given in that of Plato. Both are described as the father of Atlas, who, for practical purposes, may be called the central or pivotal figure in Atlantean history. Plato provides us with no further details concerning the Kings of Atlantis, after telling us that they reigned there "for generations." Not so Diodorus, who, it would seem, had access to a tradition or traditions of greater scope, so far as this particular part of the Atlantean story is concerned. In fact, he carries on the history of the Atlantean King until the time of Jupiter, who, he assures us, was a totally different personage from the deity of that name.

First, we have Basilea "the great mother, "the queen" par excellence y who is, of course, no other than she whom the entire Mediterranean from Carthage to Canaan, subsequently revered as the Mother Goddess, Astaroth, Astarte, Diana, Venus, Aphrodite, Isis that great maternal figure who had a hundred names, and a hundred breasts, yet one single personality, and who is also found in Britain, Ireland and Gaul, and in America, though not in Germany or among the Slavs. Her "distribution" is precisely on the lines and currents of Atlantean colonisation and emigration. Wherever her name has gone, something of Atlantis also has gone. The invading Atlanteans, Cro-Magnon and Azilian, were the first to bring her cult to Europe, as their statuettes or idols of her prove. They portray a woman with the exaggerated symbols of motherhood, as Macalister remarks. She was the goddess and along with her, as in the Atlantis of Plato, went the bull, as will be made clear when we come to consider Atlantean religion in its proper place. The myth in Diodorus which speaks of her dementia at the death of her children is, of course, the madness which, in many places in classical story, is described as forming part of her cult the fury of wild, feral Nature, as displayed in the story of Isis, and that of the Mother Goddess of Scotland, the Cailleach Mheur. The madness of Agave on the death of Pentheus is a distortion of it, the despair of Kore at the disappearance of Persephone a memory of it.

Atlas, her brother, who followed her, was, says Diodorus, a wise astrologer, the first to discover the knowledge of the sphere. Even to this day his name is connected with the science of Geography. That an entire ocean, that a mountain range still existing, should be called after him is significant. It is always the eponymous figures from whom localities and races are named, those men who grow in course of time to godhead. Hellas was the father of all the Greeks, the English have Ingwe for their sire, the Scots worshipped Scota or Skatha, whose name still survives in that of the island of Skye, the Romans took their name from Romulus, and hundreds of other races call or called themselves the children of eponymous forebears. There is, therefore, nothing unreasonable in the supposition that the people of Atlantis called themselves after Atlas, the Titan who was once a man, and gave the country his name.

Atlas, says Diodorus, married his sister Hesperis, and the pair had seven daughters, after whom the planets were said to take their names. How long Atlas reigned we have no means of knowing, but it was probably during his tenure of the throne that the city of Atlantis was founded. It could scarcely have been a place of much consideration in the reign of Poseidon the first king, and it seems much more probable that the temple which contained his image and that of Cleito, his wife, was erected subsequent to his death. Against this view, however, may be placed the fact that the statues of his ten sons were also to be found in the sacred building, and that these were very evidently the images of "ancestors," deceased men deified. It may, therefore, be safer to conclude that, although the temple and the statues of Poseidon and Cleito dated from the reign of Atlas, the statues of the deified twins were placed there at a later period.

Atlas, the astronomer, must have employed the palace on the hill above the city as his observatory. But when we speak of "temples," "palaces" and "observatories," the critic may say "let us remember that we are dealing with an epoch more than 10,000 years ago, and that the Azilian immigrants to Spain did not build such structures. That is as it may be. The fact remains that extensive works of the Azilian period have been discovered at Huelva in south-western Spain by Mrs. Elena Whishaw, of the Anglo-Spanish School of Archaeology there. Mrs. Whishaw has succeeded in bringing to light numerous evidences of that Tartessian civilization which flourished in the South of Spain in pre-Roman and even in pre-Carthaginian times. After many discouragements she succeeded in founding the Anglo-Spanish School of Archaeology in 1914, first at Seville and later at Niebla, under the patronage of King Alfonso. The museum which she has erected outside the little walled town is a model of its kind, and is filled with the result of her excavations in all their stages from Palaeolithic to Arabic times.

The great majority of the Stone Age objects housed in the Museum have been classed in accordance with the views of modern authorities as belonging to the Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age. These are of a type apparently unique, for they are not, like the Palaeolithic objects of most other regions, of flint, but of various kinds of stone, including quartz, porphyry and slate, mostly recovered from drifts of the last Ice Age. The exhibits also include many Neolithic objects and numerous fragments of pottery, exquisitely polished, some bearing designs in relief. Funeral tiles of pottery have also been encountered near Seville in connection with remains which have been classified as Cro-Magnon, so that the manufacture of earthenware objects by Palaeolithic man in this region may at least be suspected.

That a high degree of civilisation flourished in Andalusia for many ages before the occupation of the province by the Romans, is, of course, well known. The ancient kingdom of Tartessus had long been in existence at the period when the Carthaginians entered and exploited Southern Spain. The foundation of this Tartessian culture may, perhaps, be referred to the fusion of the Libyans of the Atlas region of North Africa with the Stone Age people of Spain, but such a theory does not altogether account for the high degree of engineering skill displayed in the formation of great harbours and the erection of Cyclopean walls and strongholds, the remains of which constitute the salient archaeological background of the province and exhibit many signs of pre-Tartessian handiwork. At Niebla soundings have been taken to the depths of thirty feet of soil rich in Palaeolithic remains without any sign of coming to the end of the deposit. These remains vary from miniature darts of quartz, some less than half an inch long, beautifully chipped porphyry fish-hooks and small arrow-heads, and many other minute objects of the type usually classified as Azilian, the precise use of which remains to be decided. Enormous grain-crushers, too, have been excavated, made from what is known locally as black quartz. None of these objects could have been carried down to Niebla by the river.

For some time Mrs. Whishaw was puzzled to account for the absence of Cro-Magnon dwellings in a neighbour hood so rich in Aurignacian remains. An entire series of caves exists on the banks of the Rio Tinto opposite Niebla, but it was obvious that these had not been inhabited until long after Cro-Magnon man had given place to a later race. But in the neighbourhood of the spot where many of his remains had been unearthed, and well below the foundations of Niebla, there was found the lower courses of a wall chipped in the native limestone. The association of this wall with Palaeolithic implements of Aurignacian character would certainly seem to refer its handiwork to the Cro-Magnon race, and when the excellence of Aurignacian sculpture, painting and bone-carving is recalled, the theory seems to do no violence to probability.

Later foundations have also been unearthed which have been referred to the Bronze Age. These are situated outside the walls of Niebla, facing the river on the south side, and occupying a space of about 100 feet in length. They are composed of what is locally known as hormazo, a primitive and coarser variety of the later concrete, known as hormigon, peculiar to Andalusia. The employment of one or other of these materials affords a criterion by which the approximate period of building-construction in this region can be arrived at, and this determines the early character of a Cyclopean wall of rough-hewn stones of enormous size built along the banks of the Rio Tinto to the east of the town, and held together by hormazo mortar.

This structure was revealed in 1923 by the agency of a series of floods. The river has been artificially deepened all along the wall to form a harbour, and if proof were required that such was the design of the primitive builders, it is found in a stairway over thirty feet wide cut in the rock which leads down to the river from one of the five great gate-towers of the town. The wall was doubtless built to prevent the silting-up of the artificial pool, and at the same time strengthen the defence of the city. Mrs. Whishaw has recently received permission under a royal order to excavate freely within the walls of Niebla, and hopes to learn more of the earliest phase of its history when this has been undertaken under expert direction.

Not only then, does it seem to be clear from Mrs. Whishaw's excavations that the Cro-Magnon race actually built in stone, as the Cyclopean wall in question has been found in association with their artifacts, but that the Azilian or Proto-Iberian race constructed the large ancient harbour at Huelva, and the walls and staircases there, some of which reveal work akin to that of the strange polygonal masonry of Incan Peru . Indeed , Mrs. Whishaw , an archaeologist of ripe experience, herself attributes the works in question to Atlantean immigrants, and is presently preparing an extended essay on the subject, which she is to entitle Atlantis in Andalusia.

There is thus no reason why we should not speak of "palaces" and "observatories" in the Atlantis of the time of Atlas. Probably the latter resembled the inti-huatana of Peru, Incan and pre-Incan, and there seems to be nothing wildly improbable in envisaging the sage Atlas seated in such a building, occupied with the study of the heavenly bodies.

We may infer, from the circumstance that Atlas was engaged in the researches of astronomy, that his reign was a peaceful one. In all probability it was of considerable duration, and witnessed the growth and consolidation of the Atlantean power.

Didorus tells us that Jupiter was a king of the Atlanteans, and as he is careful to assure us that this personage was not the same as the god of that name, we must infer that he was a man named after that god. But there seems to be some dubiety concerning whether Saturnus, the brother of Atlas, or Jupiter, his son, came first to the throne. "This Jupiter," says Diodorus, "either succeeded to his father Saturnus, as King of the Atlan tides, or displaced him." It would thus seem either that Saturn reigned first and left the succession to his son in the usual manner, or that Jupiter hurled him from the throne. The latter appears to be the more probable surmise, as Diodorus tells us that: "Saturn, it is said, made war upon his son, with the aid of the Titans, but Jupiter overcame him in a battle, and conquered the whole world." "Saturn," he also remarks, "was profane and covetous." We may thus assume that an irreligious and grasping old king or chieftain, whose avarice and profanity had become a menace to the body politic, was displaced by a more pious and considerate son. Saturn, we are told, availed himself of the aid of the Titans, that is, probably of the more ancient Aurignacian part of the population, the tall Cro-Magnon people, in his struggle with his son, and it is likely that this use of a people until now quiescent, had not a little to do with later unrest in Atlantis.

We may, then, regard Jupiter as the third King of Atlantis, or at least the third of whom we have any definite knowledge. It was in his reign that those elements of unrest which were to play so disastrous a part in Atlantean history began to manifest themselves. But it may be, and indeed it seems much more likely, that the four outstanding figures in Atlantean history, Poseidon, Atlas, Saturn and Jupiter, represent the founders of four separate dynasties as well as individual reigns. Indeed this may be gleaned from Plato's account, which tells us that, "for many centuries they did not lose sight of their august origin, they obeyed all the laws, and were religious adorers of the gods their ancestors." Four reigns could not cover such a length of time, and we are driven to the conclusion that the personages named were the first monarchs of new dynastic lines. This is all the more probable because they have the names of "Classical" gods, bestowed upon them by Plato's informant in default of being able to supply their Atlantean or Egyptian names in a form understandable to Greek hearers. The founders of new dynasties nearly always go down in history as beings of divine or semi-divine birth. There are several cases of the kind in Egyptian history, the first King of the Merovingian line of the Franks, Merowig, was supposed to be of supernatural birth, and Roman, Greek and Babylonian examples also exist.

This, too, provides a powerful argument that the only four Kings of Atlantis of whose names we have any record, were not gods, but human men, to whom later divine honours were paid. It would also seem to have been customary in Atlantis to deify kings after their deaths, precisely as it was in Egypt and Rome, and not infrequently among the tribes of ancient Britain and the North-American Indians. This, of course, at once accounts for their being regarded as gods by subsequent generations. They were, in fact, "gods," precisely in the sense that Numa Pompilius or Marcus Aurelius were considered as "gods" after their death.

With what we may then believe to be the dynasty of Jupiter, a revolutionary spirit seems to have manifested itself in the body politic of Atlantis. "In the course of time," says Plato, "the vicissitudes of human affairs corrupted little by little their divine institutions, and they began to comport themselves like the rest of the children of men. They hearkened to the promptings of ambition, and sought to rule by violence. Then Zeus, the King of the gods, beholding this race once so noble, growing depraved, resolved to punish it, and by sad experience to moderate its ambition."

It is here that Plato's account in the Critias ends, and I believe it to have remained unfinished because of his death. I also believe that he could have told us much more about Atlantis had he survived to elaborate his account of it. The passage in question applies, in my view, not to the events which prefaced the final catastrophe, but to that part of Atlantean history in which the spirit of revolution first reared its head. Saturn, the miserly and anti-religious occupant of the throne, had evidently aroused popular feeling against his policy, or the lack of it, and had estranged not only his subjects, but his heir. The latter probably headed a public revolt against the aged tyrant, who, unable to obtain the assistance of his subjects, had recourse to the older autochthonous stock of Aurignacians. There was, says Diodorus, a battle, in which he and his allies were defeated, and he was hurled from power.

But the Atlanteans, formerly pacific and law-abiding, had now become inoculated with the fever of party strife. Bad feeling must have been maintained between the opposing factions, even after peace had been nominally secured, and its results were probably to be witnessed in a general state of political unrest and popular disorganisation. It was evidently at this stage that Zeus through the mouthpiece of his priesthood, of course issued a general warning to the contending parties. They were probably told by the hierophants that a council of the gods had been convoked by the Allfather, at which their conduct had been condemned. After that all is darkness, so far as Plato is concerned. But there is little doubt that his account would have narrated the terms of the god's strictures and warnings, and have proceeded to acquaint us with its results, which, I believe, would have informed us of the manner in which revolution at home was put an end to by the politic resolve of the governing bodies, royal and spiritual, to divert the public attention to conquest abroad a policy which ended in the great invasion of Europe recorded by Plato in his Timceus, and by archaeology as the invasion of the Azilians.

It was probably in the reign of the King of Altantis, known as "Jupiter" that the decision to invade Europe was arrived at for the reason given above. But that the invasion in question was not the first, is made clear by the statement of Plato that the Kings of Atlantis "governed Libya as far as Egypt, and Europe to the borders of Etruria." This, as I have shown, corresponds generally to the spread of the Azilian or proto-Iberian race, but certainly not to that of the Cro-Magnon, from which we may infer that the Azilian people had made good their footing in Europe and Africa some time previously to their mass invasion of those regions.

Now it is strange, but nevertheless true, that for corroboration of the conditions of Atlantis at this particular era we are compelled to turn to a source which might in some ways appear the most unlikely to provide us with the proofs we require, yet which, when once it is carefully considered, we are bound to recognise as affording us precisely the desired measure of confirmation. I speak of the ancient literature of Britain and Ireland, the Welsh Triads and the Irish sagas and folk-romances. In the first especially we receive the fullest and most astonishing clues to the Atlantean history of the period in question. Before pursuing it farther, let us examine this data and glean from it the testimony which it undoubtedly contains regarding the obscure details of Atlantean chronicle.