|

|

History of Atlantis by Lewis Spence

Index | Chapter: 1 | 2 |3 | 4 |5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |9 | 10 |11 | 12 |13 | 14 |15 | 16

CHAPTER XI.

LIFE IN ATLANTIS

FROM what has gone before, we should now be able to draw such conclusions as will afford us a reasonably trustworthy picture of life in Atlantis at the period of its last phase that preceding its final submergence. We have already gleaned some information regarding its conditions during the earlier period, and must now approach its "reconstruction" as a community probably much on the same level of 'civilisation as was Mexico at the arrival of Cortez, or China before the era of European intervention, with, of course, the exception that its people were unacquainted with metals of any kind.

In the course of centuries the face of the island-continent must have undergone great changes under the civilising agency of a race eminently well fitted for the tasks of advancement. Plato's account speaks of canals more than a thousand miles long and roads which evidently stretched far inland. The circumstance that the country was divided into cantons and that each land -owner was bound by law to furnish his quota of men for the Army and Navy, leads to the assumption that a very considerable part of it was cultivated and that it had also a fairly large sea-faring population. But it can scarcely be doubted that very large tracts of wild and desert region existed, and that, indeed, the greater part of the island was still under those tundra conditions which prevailed in Europe at the era in question. The presence of a great mountain-range must have affected both agriculture and the general climatic conditions, and it is possible that Atlantis must have been densely afforested in parts.

We hear of no other towns or cities excepting the capital, but we cannot doubt that others existed. It is possible to gather a general idea of the style of architecture in vogue, both from the account of Plato, and the researches of the Anglo-Spanish School of Archaeology at Huelva in Spain, already alluded to. Plato states that the style of architecture affected by the Atlanteans was "barbaric," and this to a Greek certainly meant "Oriental." He tells us that the exterior of the great temple of Cleito and Poseidon was garnished with silver, that its pinnacles glittered with gold, and that the interior was roofed with ivory, gold, silver and orichalcum, or copper. But in view of a complete ignorance of all metals on the part of the Azilians, such a description is certainly misleading. It is much safer to rely upon the results of the recent Spanish excavations at Huelva, and regard Atlantean architecture as of the "Cyclopean" type, such as is encountered at Mycenae and elsewhere.

Such buildings are constructed of large blocks of stone accurately squared, with well-fitting beds and joints, but unequal in size. Enormous monoliths were usually employed for gateways. But the term "Cyclopean" is also given to walls constructed of polygonal blocks, which in many cases are fitted together with great skill and care. Examples of this species of masonry exist not only in Greece, but also in many sites in Etruria and America, and there can be no doubt of the extreme antiquity of the method employed.

Examples of this particular kind of architecture are to be encountered in many parts of Europe and Asia, and, indeed, it seems clear that it is nothing more or less than a form of the ancient Atlantean mode of building construction. The people who introduced it to Europe, whence it probably spread eastward, were undoubtedly the proto-Iberians, the "Mediterranean Race" of Sergi, and the earliest sites on which it has been discovered seem to justify the assumption of its introduction from a Western area. It certainly did not progress in historical succession from East to West, as the Iberians, the builders of these venerable monuments, did not originate in the eastern region of the Mediterranean. As much may be said of the rough stone monuments usually associated with Iberian handiwork, the stone circles, menhirs and dolmens of Britain, France and the Iberian Peninsula, the brochs of Scotland, the great stone forts of Ireland, the nuraghi of Sardinia, and the similar talayats of the Balearic Isles. It has also been shown that the rough stone monuments of Portugal are practically all to be found near the Atlantic sea-coast, and very few inland.

I have also shown elsewhere that the general architectural plan of the city of Atlantis, as described by Plato, appears to have been copied far and wide. It is well known that the plan and outline of the great cities of antiquity were frequently carried out in their colonial settlements, and many sites, both in Europe and Africa, appear to have been copied from the Atlantean model. Of these the most outstanding is Carthage, the plan of which is almost identical with that of Atlantis. Indeed, both Atlantis and Carthage had a citadel hill encircled by zones of land and water, a canal to the sea, and bridges over the zones, fortified by towers. In both cases the docks were roofed in, the cities were encircled by three walls, both had great cisterns for the supply of drinking water and baths, and both were guarded by a great sea-wall, masking the entrance to the harbour.

This circular design, "an island within an island," was formerly fairly common in West Africa. Hanno, the Carthaginian voyager, discovered such a plan in that region, and it is indubitably found also in America, especially in the ancient plan of the Aztec city of Mexico - Tenochtitlan and elsewhere.

The question of the presence of pyramids in Atlantis also arises. It seems unlikely that they were actually to be found there, but it is probable that the pyramid in Egypt and America is merely a later reminiscence of the sacred hill of Atlantis. In early Egypt, Mexico and Peru certain hills were regarded as especially sacred, as the homes of powerful supernatural beings. In Mexico the mountain was regarded as the home of the Goddess of Fertility, and in some parts of that country it was faced with stone, like the Egyptian pyramid, although in the region inhabited by the Mound Builders of the Mississippi, it was constructed from earth alone. The link between the Mexican pyramid constructed from masonry and the simple earthern hill is provided by the earthern mound sacred to the goddess Coatlicue close to the teocalli or pyramid of her son, Uitzilopochtli, at Mexico. Personages of importance were buried in these American pyramids just as they were in those of Egypt, which were also obviously developed from the idea of the sacred mountain. Indeed several of the Egyptian pyramids were called by such names as "Mountain of Ra," and similar titles.

Egyptian and American pyramids have thus a common evolutionary history. The idea must have sprung from a common centre. Both would appear to trace their descent from the sacred hill of Atlantis. Moreover, pyramids were to be found in the Canaries and the Antilles, the insular links in the chain between Europe and America, of which Atlantis is the missing link.

The food supply of the Atlanteans has been outlined by Plato. He states that the island produced a wealth of roots, fruits, vines and corn, but in this latter statement he is, perhaps, corrected by Diodorus, who, writing of the island Hesperia, which in this case is to be identified with Atlantis, says that corn was unknown to its inhabitants. Corn, the grain of Kore or Demeter, the agricultural goddess of Crete, is generally supposed to have been first cultivated in that country, or in Egypt, from a comparatively wild "grass," believed to be native to the Fayyoum or to Southern Palestine. But its origin is wrapped in impenetrable mystery, and the fact that it was so closely associated with the Eleusinian mysteries and with those of Osiris, both of which had a Western origin, might, perhaps, be taken as good evidence that it originated in Atlantis, although it would not be wise to dogmatize on the point. The fruit with the hard rind grown in Atlantis which afforded both meat, drink and ointment has already been alluded to, and was obviously the coconut, or some species thereof.

Animal food was supplied by cattle, large flocks of sheep and goats, and fish. The great plains would supply plenty of pasture to the ruminant animals, but it is unlikely that the horse was regarded as a food animal, as in the early ages, once it had become a beast of burden. The same applies to the elephant. That this animal was used in war is most probable. It will be recalled that the Carthaginians, who had many Atlantean memories, employed it for this purpose against the Romans and the Iberian tribes of Spain.

A notion of the costume and dress of the Atlanteans can only be gathered from the drawings which the Azilians have left us of themselves. These seem, to the writer, to resemble somewhat the costume of the Cretans of the Minoan period. In most of the upper Palaeolithic engravings of Europe the men are naked, but the man of Laussel wears a narrow girdle. The women, in the Spanish paintings, however, are usually clothed in a skirt which reaches from just above the waist to a little below the knees, leaving the upper part of the body bare. But it would not be reasonable to infer from these pictures that almost complete male nudity was universal, or even customary. Ceremonial costumes were certainly worn by the priests, as seen in the dancing figures from Vabri Megt who wear skins and animal masks, and the circumstance that many of the dead were wrapped in skins and leather jerkins on which shells had been sewn, justifies the assumption that in life they wore similar garments. The head-dresses of the statuettes found at Willendorf and Brassempouy closely resemble Egyptian head-coverings, and a number of the men in the Alpine paintings are represented as wearing plumed headdresses very like those still in use among Red Indian tribes. Others wear hats of high triangular shape, not unlike a Scots bonnet, and some of the women conical caps, made, perhaps, of bark or fur. Some of the men wear plumed bands beneath the knee and round the ankles like the Masai of south-eastern Africa; and probably both sexes wore ornaments of shells and teeth, painted or plain. Indeed, the general costume of the Azilians seems to have resembled that of the Aztecs of Mexico in some of its aspects, as well as that of the early Mediterranean peoples.

Did the Atlanteans possess a literature, and, if so, was it expressed in written documents, or merely handed down orally? From the general tendency of their civilisation, as well as from other circumstances, one is tempted to believe that both a written and an oral literature flourished among them. We have already seen that the so-called alphabetic pebbles found among Azilian remains are more probably representations of the human form expressed conventionally and symbolically, but that is not to say that the more civilized Azilians of

Atlantis did not possess some system of writing, hieroglyphic or pictorial. The mere fact that the Azilians of Europe possessed something in the nature of a symbology is pretty good proof that their contemporaries in Atlantis had at least advanced as far as the use of a pictorial writing similar to that by which the Aztecs of Mexico expressed themselves, keeping accounts of tributes, fixing the date of religious festivals, and even chronicling the facts of history as well as the fancies of fiction. Plato, in stating that the laws of Atlantis were engraved on a column of orichalcum implies that they possessed some system of writing.

On this subject we may, perhaps, quote the opinion of Dr. T. Rice Holmes: "Many people have heard vaguely of the painted pebbles and the frescoes of Mas d'Azil and the other caverns in the Western Pyrenees which the veteran archaeologist, Edouard Piette, has for many years diligently searched. On one of the objects found in the cavern of Lorthet a spirited engraving on reindeer-horn representing reindeer and salmon are to be seen two small lozenges, each enclosing a central line: 'Justly proud of his work,' says Monsieur Piette, 'the artist has appended his signature.' Be this as it may, other explorers have exhumed from the Placard cave at Rochebertier and the caves of La Madelaine and Mas d'Azil antlers incised with signs which exactly resemble various Greek and Phoenician letters, and may be compared with signs that have been found in an island of the Pacific. These signs are not letters but symbols; they are not combined in such a way as to form words or inscriptions. 'But,' says Monsieur Piette, 'being symbols, they do constitute a kind of primitive writing.' True writing is, however, evident on a potsherd taken from a neolithic settlement at Los Murcielagos in Portugal.

If this fragment could itself be proved to be of neolithic age, it would follow that in that remote time the art of writing was already known to at least one branch of the Mediterranean stock."

If we examine the history of writing and symbolism in Europe and America, certain facts emerge which might, after all due caution was employed, point to an Atlantean origin for certain elements in both European and American symbols and glyphs. It is not claimed for a moment that the European alphabetic system which we presently employ is other than Phoenician in origin, with a possible Egyptian background. But the known origin of all systems of writing in symbolism, the identity of many European, Egyptian and American symbols which were used for the purposes of communication, and the obvious necessity for presupposing for these a link situated in an Atlantean locality, are circumstances which plead for careful consideration.

The late Augustus Le Plongeon professed to find complete identity between the Egyptian and Central American forms of hieroglyphic writing. But as a student of the latter, who has also more than a passing acquaintance with the script of Egypt, the present writer is quite unable to discern any superficial resemblances between Egyptian and Maya or Mexican writing, and cannot subscribe to Dr. Le Plongeon's "translations" of Maya inscriptions and manuscripts. That affinities do exist is certain, but, when revealed, they will be found to lie much deeper than Dr. Le Plongeon believed, and to have been communicated by channels very different from those he considered as having borne them.

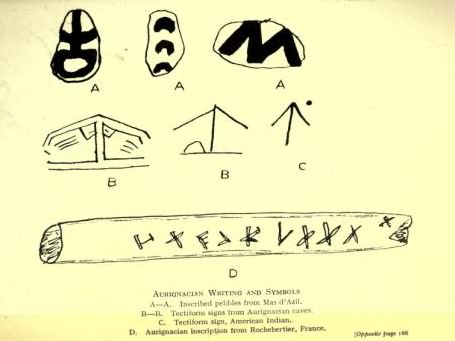

The fact that certain symbols, described as "tectiform" or "roof-formed" by some anthropologists, occur on the painted representations of buffaloes, both in Aurignacian caves and in the drawings of the Plains Indians of America is a good central point to start from in such a discussion, and serves to prove almost at once a symbolical connection between Europe and America. That these have no mere fortuitous resemblance is obvious, and this is rendered more clear by the circumstance that they occupy the same position on the body of the animal.

Says Macalister: "Some of these marks or groups of marks have been claimed as proving the astonishing theory that Magdalenian man had evolved a form of writing by symbolic signs." Yet if the paintings from Alpera and elsewhere reveal anything to the student familiar with the origins of picture-writing, it is that those who created them were on the verge of discovering some such system. They are every whit as much of the nature of picture-writing as the similar drawings of the American Indians, Australians and Eskimos, or as the well-known Aztec story-book usually called the Codex Nuttall, in which the life-story of a hero is told by pictures along with which only a few symbols of names appear as "text." In places in the great Alpera wall-painting appear symbols precisely the same as those found on the painted Azilian pebbles, which proves conclusively that they were used as symbols, and probably name-symbols at that, and above these in more than one place are strokes evidently referring to numbers, and associated with the name-symbols in question. Moreover, in this especial instance, the "tectiform" device is apparent in association with these names and numerals, and the numerals are precisely similar to those in use among the Maya to express the figure "five." The entire scene, I believe, is not only the record of a great hunt, but of the names of some of the heroes who took part in it, and of the number of beasts accounted for. Now, practically the self-same symbols as appear in Azilian art are to be found in the picture-writings of the North American Indian tribes as the appended illustrations show. The American Indian symbols are assuredly connected with the more highly conventionalised writing systems of the Mexicans and Maya, just as the Azilian are, on the other hand, with those of Egypt and Babylonia. No other conclusion can be reached, then, save that the early pictorial symbols of the Old World and the New must have originated from one common source probably in the Atlantic area. If we deny this, we must assume either that the symbols of the Old World and the New are of separate and spontaneous origin, or that these Azilian symbols reached America via Asia.

The first assumption is one now generally rejected by students of symbology for the very obvious reasons that man is by no means an original "animal," and that symbological resemblances are usually much too precise to be fortuitous. The second is equally frail, because we find all the advanced systems of picture-writing in America strongly established on the Eastern side of the continent, and only their modern, broken-down or degenerate remains on the Western Coasts.

Arguing from such data, then, it seems reasonably clear that the symbolic system of painting anciently in use in both Europe and America must have had its inception in some area whence it could easily have been communicated to both. Such an area could only have existed in the Atlantic Ocean. Indeed, as I have already shown elsewhere a considerable proportion of the symbols in use among the Maya had a definite bearing upon a tradition of cataclysm. Moreover, these symbols are now known to students as " calculiform " or pebble-shaped, and seem to have been developed from painted pebbles, like the Azilian writing.

There is thus no good reason for denying to the Atlanteans the art of picture-writing, in an elementary form at least, and probably as highly developed as that which subserved the purposes of the great and far-flung Aztec Empire. Doubtless they had their civil and religious books, carved on stone or painted on cavern walls. As we have seen, the Canary Islands abound in caverns, " Where," says Osborn, "the ceilings were covered with a uniform coat of red ochre, while the walls were decorated with various geometric designs in red, black, grey and white." Rene Verneau, a French anthropologist of experience, writes of them: "All these walls (in the Grotto of Goldar) are decorated with paintings." 2 Thus, in the last remaining portion of Atlantis, proof is forthcoming that its ancient inhabitants possessed a symbolism of their own. All symbolism is merely a stage on the way to written expression, and pictures are as much thoughts brought to sight as words or printed pages. Nor is it likely that the dwellers in these caverns, shepherds or hunters, would have been on an equal cultural level with the inhabitants of the cities of Atlantis, any more than the shepherds of the Vosges are the cultural equals of the literati of Paris, or the cowboys of the far West the intellectual peers of the scholars of Boston or New York.

Regarding the manners and morality of the people of Atlantis, we are enabled to speak with greater freedom. All authorities are at one in arguing that the latter were by no means praiseworthy. Plato, indeed, paints rather a black picture of the morals of the Children of Poseidon. But we must remember that he is in some respects biased, as he was obviously endeavouring to make the Atlantean power a foil to his own native state of Athens, to play the one off against the other, to show that the Poseidonians, the progeny of the rather obnoxious sea-god, were by no means the equals either in morality or courage, of the People of Pallas Athene. There are, however, other good reasons why we may regard the later Atlanteans at least as a people who were by no means without blame. As I have said before, it seems perfectly possible that Atlantis may have survived until a considerably later date than Plato fixed for its submergence, and if this be so, we have a period of time in which its people may have advanced from the comparative state of barbarism which undoubtedly distinguished them in Azilian times to a condition of much greater mental complexity than was possible in that era.

If this be so, their invasion of the soil of their neighbours speaks badly for their general state of mind. Nor does the cruel sport of bull-baiting, which they appear to have indulged in, afford other than a picture of brutality which chimes ill with their alleged culture.

May it not be that the vices usually attributed to the "Antediluvians " in the sacred writings of many peoples are nothing but a memory of the flagrant behaviour of the Atlanteans, who similarly perished by flood? The Scriptures assure us that the divine or heavenly race had become corrupted through intermarriage with the earthly denizens of the world. "The sons of God (or civilised race) saw the daughters of men (aborigines) that they were fair ; and they took them wives of all which they chose." This was precisely what Poseidon and his sons did. There were also, we are told, "giants (Titans) in the earth in those days." So evil did men become that the Creator resolved to destroy them.

In the seventy-first chapter of the Koran Noah is made to recite a prayer which shows clearly that, according to the traditions of the Mussulmans the Antediluvian race perished because of its sins. " Lord, leave not any families of the unbelievers on the earth, for if thou leavest them they will seduce thy servants, and will beget none but a wicked and unbelieving offspring," but this prayer, we are told was not actually uttered by Noah until he had found the Antediluvians to be reprobate and incorrigible during the 950 years he is said to have tried them. Noah also exclaimed: "Lord, forgive me and my parents, and every one who shall enter my house, and add unto the unjust doers nothing but destruction." On this subject the Oriental commentators on the Koran are divided, some maintaining that Noah here referred to his own dwelling-house, and others to the temple he had built for the worship of God, or to the Ark then in progress.

The Koran affirmed that Noah, while he was building the Ark, often replied to the scoffings of the unbelievers in this manner: " Though you scoff at us now, we will scoff at you hereafter, as ye scoff at us ; and ye shall surely know on whom a punishment shall be inflicted, which will cover you with shame, and on whom a lasting punishment shall fall."

In the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh the god Ea grows angry at the sinfulness of the people of Suruppak, and precipitates such a disastrous flood that "no continent appeared on the waste of waters." The Greek myth of Deucalion states that the Antediluvians "were insolent, and addicted to unjust actions ; they neither regarded oaths nor were they hospitable to strangers nor listened to suppliants; and this complicated wickedness was the cause of their destruction. Of a sudden the earth poured forth a vast quantity of water . . . and all men were destroyed." Ovid, in his Latin account of the Deluge makes Jupiter say: "It were endless to repeat the aggravated guilt which everywhere appeared." Egyptian legend relates that the god Tern let loose the waters of the primeval abyss over the earth to destroy mankind because of its wickedness.

Vishnu, in Hindu myth, sends a flood upon the earth because "all creatures had offended him." In Breton legend the city of Ys is overwhelmed by the waters because of the profligacy of its princess, "who had made a crown of her vices, and taken for her pages the seven capital sins." In a myth of the Arawak Indians the god Aimon Kondi scourges the world with fire, followed by a flood, because of the shortcomings of man, and countless other myths speak of the drowning of the human race for its wickedness. That a myth so widespread could have arisen without some most definite cause seems highly improbable. It is much more likely that evidence so overwhelmingly united must have behind it an actual historical condition.

Not the least valuable evidence from America is the myth of the destruction of the wicked as given by Mr. Jeremiah Curtin in his Creation Myths of Primitive America, and as described by an American Indian:

"There was a world before this one in which we are living at present. That was the world of the first people, who were different from us altogether. Those people were very numerous, so numerous that if a count could be made of all the stars in the sky, all the feathers on birds, all the hair and fur on animals they would not be so numerous as the first people.

"These people lived very long in peace, in concord, in harmony, in happiness. No man knows, no man can tell, how long they lived in that way. At last the minds of all except a very small number were changed. They fell into conflict one offended another, consciously or unconsciously, one injured another with or without intention, one wanted some special thing, another wanted that very thing also. Conflict set in, and because of this came a time of activity and struggle, to which there was no end or stop till the great majority of the first people that is all except a small number were turned into the various kinds of living creatures that are on earth now or have ever been on earth except man that is, all kinds of beasts, birds, reptiles, fish, worms and insects, as well as trees, plants, grasses, rocks and some mountains. They were turned into everything that we see on the earth or in the sky.

"The small number of the former people who did not quarrel, those great first people of the old time who remained of one mind and harmonious, left the earth, sailed away westward, passed that line where the sky comes down to the earth and touches it, sailed to places beyond; stayed there or withdrew to upper regions and lived in them happily, lived in agreement, live so to-day, and will live in the same way hereafter."

Surely such a world-wide memory of the profligacy of the Atlanteans cannot possibly have sprung from chance invention. We see that it deals with a world submerged for its vices, as Atlantis was. It is, then, possible to speak, as we shall see later, of pre-Platonic evidence for Atlantean history.