|

|

History of Atlantis by Lewis Spence

Index | Chapter: 1 | 2 |3 | 4 |5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |9 | 10 |11 | 12 |13 | 14 |15 | 16

CHAPTER V.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF ATLANTIS

WE must now consider the geographical questions connected with the site and topography of Atlantis. With these is inevitably bound up the problem of its actual existence. We are not dealing with a Greece or a Rome, an Egypt or an Assyria, but with a continent submerged, the very existence of which is in some quarters strenuously denied. In the first place, then, before we proceed to draw conclusions with reference to its geographical position and physiographical features from the literary sources at our command, we are compelled to examine such geological proof as we possess that Atlantis existed at all. This must, indeed, be satisfactorily demonstrated before we can reasonably regard the island of Atlantis as a fit subject for anything approaching an historical thesis.

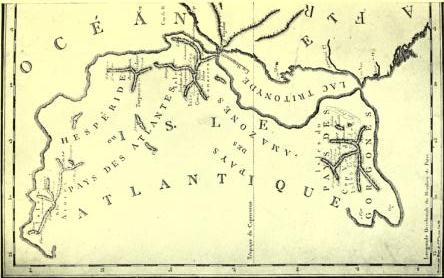

ATLANTIS IN TERTIARY TIMES (After R. M. Gattefosse).

The geological proof for the existence of Atlantis is extensive, and in this place can only be summarized. A full account of it will be found in my former works The Problem of Atlantis and Atlantis in America. It is here conceded that the only portion of geological time which has a definite bearing on the problem is the Quaternary epoch, which embraces the Pleistocene or Ice Age, and the commencement of which may, for practical purposes, be placed about 500,000 years ago. The Quaternary is subdivided into four glacial epochs and one post-glacial epoch. It is only in this post-glacial epoch, which probably began about 25,000 years ago, that any human form approaching modern man is to be discovered in Europe. If, then, we are to posit an Atlantis peopled by human types recognizable as modern, the period in which we must do so is confined to the last 25,000 years of European history. Does modern geology uphold the probability of the existence of an Atlantean continent at any time during this period?

M. Pierre Termier, Director of Science of the Geological Chart of France, is one of a growing band of geologists who devoutly believe that a great Atlantean continent existed during the period in question. With the gradual collection of new evidence relative to the geology and the biology of the Atlantic region, the theory concerning the existence of such a land-mass has taken on an entirely new complexion. This evidence does not depend upon the misty surmises of visionaries, or the dogmatic assertions of that type of antiquary who twists tradition and philology into the semblance of testimony, but on considerations the most rational and credible. That an Atlantean continent at one time occupied the present oceanic gulf between Europe and America is a scientific truth now accepted by geologists of all shades of opinion, and the only question of debate which still remains has reference to the precise period in geological history at which this continent flourished.

The bed of the Atlantic is the most unstable part of the earth's surface, says M. Termier. Its eastern region is a great volcanic zone. In its European-African depression sea-volcanoes and insular volcanoes are abundant. Its islands are largely formed of lava, and a similar formation occurs in its American or western region. The bed of the Atlantic, this authority assures us, is still in movement, in its extreme eastern zone, for a space of about 1,875 m iles in breadth, which embraces Iceland, the Azores, the Canaries, Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands. In any part of this area unrecorded submarine cataclysms may be taking place at any time.

M. Termier believes that a North Atlantic continent formerly existed, comprising Russia, Scandinavia, Great Britain, Greenland and Canada, to which was added later a southern band made up of a large part of Central and Western Europe and an immense portion of the United States. "There was also," he says, "a South Atlantic or African-Brazilian continent, extending northward to the southern border of the Atlas, eastward to the Persian Gulf and Mozambique Channel, westward to the eastern border of the Andes and to the sierras of Colombia and Venezuela. Between the two continents passed the Mediterranean depression, that ancient maritime furrow which has formed an escarp about the earth since the beginning of geologic time, and which we see so deeply marked in the present Mediterranean, the Caribbean Sea, and the Sunda or Flores Sea. A chain of mountains broader than the chain of the Alps, and perhaps in some parts as high as the majestic Himalayas, once lifted itself on the land-enclosed shore of the North Atlantic continent, embracing the Vosges, the Central Plateau of France, Brittany, the south of England and of Ireland, and also Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and, in the United States, all the Appalachian region."

The end of this continental era, thinks M. Termier, came during the Tertiary Period, or that before the Quaternary, when the mass, bounded on the south by a chain of mountains, was submerged long before the collapse of those volcanic lands of which the Azores are the last vestiges. The South Atlantic Ocean was likewise occupied for many thousands of centuries by a great continent now engulfed beneath the sea. These movements of depression probably occurred at several more or less distantly removed periods. In the Europe of the Tertiary era the movement was developing which gave rise to the Alpine mountain chain. How far did this chain extend into the Atlantic region? Did some fragments of it rise high enough to lift themselves for some centuries above the waters? This question M. Termier answers in the affirmative.

He believes that the geology of the whole Atlantic region has singularly altered in the course of the later periods of the earth's history. During the Secondary period there were numerous depressions, the Tertiary Period saw the annihilation of the continental areas, and subsequently there appeared a new design, the general direction of which was not east and west as formerly, but north and south. Near the African coast, he holds, there have certainly been important movements during Quaternary times, when other changes undoubtedly took place in the true oceanic region. " Geologically speaking," he says, "Plato's theory of Atlantis is highly probable. . . . It is entirely reasonable to believe that long after the opening of the Strait of Gibraltar certain of these emerged lands still existed, and among them a marvellous island, separated from the African continent by a chain of other smaller islands. One thing alone remains to be proved that the cataclysm which caused this island to disappear was subsequent to the appearance of man in Western Europe. The cataclysm is undoubted. Did men then live who could withstand the reaction and transmit the memory of it? That is the whole question. I do not believe it at all insoluble, though it seems to me that neither geology nor zoology will solve it. These two sciences appear to have told all they can tell, and it is from anthropology, from ethnography, and lastly from oceanography that I am now awaiting the final answer."

Criticising this statement, Professor Schuchert writes: "The Azores are true volcanic and oceanic islands, and it is almost certain that they never had land connections with the continents on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. If there is any truth in Plato's thrilling account, we must look for Atlantis off the western coast of Africa, and here we find that five of the Cape Verde Islands and three of the Canaries have rocks that are unmistakably like those common to the continents. Taking into consideration also the living plants and animals of these islands, many of which are of European-Mediterranean affinities of late Tertiary time, we see that the evidence appears to indicate clearly that the Cape Verde and Canary Islands are fragments of a greater Africa. . . . What evidence there may be to show that this fracturing and breaking down of western Africa took place as suddenly as related by Plato, or that it occurred about 10,000 years ago, is as yet unknown to geologists."

Professor R. F. Scharff, of Dublin, who has perhaps contributed more valuable data to the literature of Atlantean research than any other living scientist, concludes that Madeira and the Azores were connected with Portugal in Miocene or later Tertiary times, when man had already appeared in Europe, and that from Morocco to the Canary Islands and thence to South America stretched a vast land which extended southward as far as St. Helena. This great continent, he believes, began to subside before the Miocene. But he holds that its northern portions persisted until the Azores and Madeira became isolated from Europe. "I believe," he says, "that they were still connected in early Pleistocene (Ice Age) times with the continents of Europe and Africa, at a time when man had already made his appearance in Western Europe, and was able to reach the islands by land."

Among those modern geologists who uphold the Atlantean theory is Professor Edward Hull, whose investigations have led him to conclude that the Azores are the peaks of a submerged continent which flourished in the Pleistocene period. "The flora and fauna of the two hemispheres," says Professor Hull, "support the geological theory that there was a common centre in the Atlantic, where life began, and that during and prior to the glacial epoch great land-bridges north and south spanned the Atlantic Ocean." He adds: "I have made this deduction by a careful study of the soundings as recorded on the Admiralty charts." Dr. Hull also holds the view that at the time this Atlantic continent existed there was also a great Antillean continent or ridge shutting off the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico from what is called the Gulf Stream.

These considerations would appear to sustain the contention of modern geologists that the bed of the Atlantic has undergone constant change, and that, indeed, it may have risen and sunk many times since the period of the last Ice Age, as Sir William Dawson once stated.

From such evidence we may be justified in concluding that the hypothesis of a formerly existing land-mass in the Atlantic Ocean is by no means based on mere surmise. The fact that geologists of distinction have risked their reputations by testifying in no uncertain manner to the reality of a former Atlantean continent should surely give pause to those who impatiently refuse even to examine the probabilities of the arguments so ably upheld. But the most significant consideration which emerges is that this >modern expert evidence is almost entirely in favour of the existence of a comparatively recent land-mass or masses in the Atlantic, and if we take into consideration the whole of the evidence, and the nature of its sources, it does not seem beyond the bounds of human credence that at a period probably no earlier than that mentioned by Plato in his Critias, viz. 9600 B.C., this ancient continent was still in partial existence, but in process of disintegration that an island of considerable size, the remnant, perhaps, of the African 'shelf," still lay opposite the entrance to the Mediterranean, and that lesser islands connected it with Europe, Africa, and, perhaps, with our own shores.

Dealing with the improbability of such an island as Atlantis, ever having existed, Mr. W. H. Babcock objects that: The advocates of a real Atlantis try to pile up proofs of a great land-mass existing at some time in the Atlantic Ocean, a logical proceeding so far as it goes, but one that falls short of its mark, for the land may have ascended and descended again ages before the reputed Atlantis period. It is of no avail to demonstrate its presence in the Miocene, Pliocene, or Pleistocene epoch, or, indeed, at any time prior to the development of a well organised civilisation among men, or, as Plato apparently reasons, between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago. Also what is wanted is evidence of the great island Atlantis, not of the former seaward extension of some existing continent, nor of any land-bridge spanning the ocean. It is true that such conditions might serve as distant preliminaries for the production of Atlantis Island by the breaking down and submergence of the intervening land, but this only multiplies the cataclysms to be demonstrated and can have no real relevance in the absence of proof of the island itself. The geologic and geographicphenomena of pre-human ages are beside the question. The tale to be investigated is of a flourishing insular growth of artificial human society on a large scale, not so very many thousands of years ago, evidently removed from all tradition of engulfment and hence dreading it not at all, but sending forth its conquering armies until the final defeat and annihilating cataclysm."

The reader will observe that I have not "tried to pile up proofs of a great land-mass existing at some time in the Atlantic Ocean," otherwise than to permit him to follow the general argument with clarity, but that I have confined most of the geological evidence to that part of it which deals with the possible existence of Atlantis at the period indicated in Plato's myth. As regards the portion of Mr. Babcock's statement which relates to the condition of "human society on a large scale" to be found in Atlantis, I have never subscribed to this notion, but have, in my former works, indicated that I believed such human society as Atlantis boasted to be of a comparatively primitive character. The protagonist of the Atlantis theory need not rely solely upon the evidence of Plato, as Mr. Babcock appears to think. To do so would unduly and unnecessarily limit the sphere of both proof and inquiry.

The soundings taken in the Atlantic by various Admiralty authorities have revealed the existence of a great bank or elevation commencing near the coast of Ireland, traversed by the fifty-third parallel, and extending in a southerly direction embracing the Azores, to the neighbourhood of French Guiana and the mouths of the Amazon and Para Rivers. The level of this great ridge is some 9,000 feet above the bed of the Atlantic. Soundings taken by the various expeditions of the Hydra, Porcupine and Challenger during the nineteenth century especially uphold the hypothesis of the former existence of land in the Atlantic region.

Regarding the relationship of the submarine banks of the North Atlantic to the problem, Mr. W. H. Babcock writes: "All of these subaqueous mountain-top lands or hidden elevated plateaus are conspicuously nearer the ocean surface than the real depths of the sea so much nearer that they inevitably raise the suspicion of having been above that surface within the knowledge and memory of man. It is notorious that coasts rise and fall all over the world in what may be called the normal non-spasmodic action of the strata, and sometimes the movement in one direction upward or downward seems to have persisted through many centuries. If we assume that Gettysburg Bank has been continuously descending at the not extravagant rate of two feet in a century then it was a considerable island above water about the period dealt with by the priests of Sais. Apparently the rising of Labrador and Newfoundland since the last recession and dispersion of the great ice-sheet has been even more. Here the elements of exact comparison in time and conditions are lacking; nevertheless, the reported uplift of more than 500 feet in one quarter and nearly 600 in another is impressive as showing what the old earth may do in steady endeavour. It must be borne in mind, too, that a sudden acceleration of the descent of Gettysburg Bank and its consorts may well have occurred at any stage in so feverishly seismic an area. All considered, it seems far from impossible that some of these banks may have been visible and even habitable at some time when men had attained a moderate degree of civilisation. But they would not be of any vast extent."

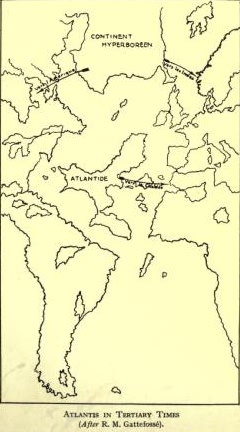

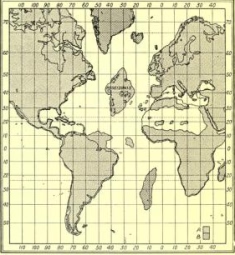

MAP SHOWING PROBABLE RELATIVE POSITION OF ATLANTIS (A) AND ANTILLIA (B)

But we have even more valuable evidence from other sources than from geology alone. The evidence afforded from biological research is even more remarkable. Professor Scharff in his paper already quoted from has made it clear that the larger mammalia of the Atlantic islands were not imported, and states that his endeavours to trace "the history of their origin on the islands point rather to some of them, at any rate, having reached the latter ' in the normal way, which is by a land-connection with Europe."

The reptilian fauna of the Atlantic islands is almost entirely European in character. Among the lizards, a North African and a Chilian form are allied. The large family of the burrowing Amphisbaenidae is absolutely confined to America, Africa, and the Mediterranean region. In his monograph on the mollusca of the Atlantic islands Mr. T. V. Wolias ton drew attention to the fact that the Mediterranean element is much more traceable in the Canaries than in any other groups of islands. He believes that the Atlantic islands have originated from the breaking-up of a land which was once more or less continuous, and which had been intercolonised along ridges and tracts now lost beneath the ocean.

Professor Simroth, writing on the similarity between the slugs of Spain, Portugal, North Africa, and the Canaries, concluded that there was probably a broad land-connection between these four countries, and that it must have persisted until comparatively recent times. Dr. W. Kobelt, who formerly ridiculed the Atlantean theory, later altered his views. Comparing the European with the West Indian and Central American fauna, he points out that the land shells on the two opposite sides of the Atlantic certainly imply an ancient connection between the Old World and the New, which became ruptured only toward the close of the latter part of the Tertiary period. Dr. von Ihering lays stress on the fact that no malacologist nowadays could explain the presence of these continental molluscs on the Atlantic islands in any other way but by their progresssion on land.

The presence of large hawks or buzzards, observed by the discoverers of the Azores in 1439, led to the islands receiving the name of Azores, or Hawk Islands. These birds usually live on mice, rats, and young rabbits, and this implies the existence of such mammals on the islands. It appears to be substantiated that the existence of the Azores had already been known to earlier navigators, for in a book published in 1345 by a Spanish friar the Azores are referred to, and the names of the several islands given. On an atlas published at Venice in 1385 some of the islands are mentioned by name, as Capraria, or Isle of Goats, now San Miguel; Columbia, or Isle of Doves, now Pico; Li Congi, Rabbit Island, now Flo res; and Corvi Marini, or Isle of Sea Crows, now Corvo. This nomenclature given prior to the discovery the "official" discovery of the islands, that is seems to justify the assumption that mammals such as the wild goat and the rabbit flourished there at that period, and had reached the islands from Europe by a land-connection at a remoter era.

Certain zoologists, says Professor Scharff, recognise a distinct division of the marine area of the globe as consisting of the middle portion of the Atlantic, which they call " Mesatlantic." Two genera of mammals are assigned as characteristic of this region the Monachus or Monk Seal, and the Sirenian Manatus. Neither of these animals frequents the open ocean. Their several species inhabit the Mediterranean, the West Indies, and the coasts and estuaries of the West African and East South American sea-boards. The range of these marine animals seems to many zoologists to imply that their ancestors have spread along some coast-line which formerly united the Old World and the New at no very distant period.

Sixty per cent, of the butterflies and moths found in the Canaries are of Mediterranean origin, and twenty per cent, of these are to be found in America. Some crustaceans afford proof of the justice of the Atlantean hypothesis. The genus Platyarthus is represented by three species in Western Europe and North Africa, one in the Canaries and one in Venezuela. "There is," says Scharff, "another group of Crustacea which yields such decisive indications of the former land-connection between Africa and South America that scarcely anything else is needed to put that theory on a firm basis. The group referred to is that of the fresh-water decapods, the species on both sides of the Atlantic showing a most remarkable affinity."

Experiments have shown that certain snails cannot withstand prolonged immersion in sea-water. Yet these species are found alike in Europe, America, and the Canary Islands. It is therefore manifest that they must have progressed thence by land. Many similar parallels could be drawn from plant life, if space permitted.

At the same time there are biologists who absolutely refute the notion of a land-bridge between the New and the Old World, and who believe the Old World type reached America by way of Behring Strait. This, however, has always appeared to the writer as a hypothesis much more difficult of belief than the Atlantean. The conclusions arrived at in a former work by aid of this evidence were as follows:

That a great continent formerly occupied the whole or major portion of the North Atlantic region, and a considerable portion of its southern basin. Of early geological origin, it must, in the course of successive ages, have experienced many changes in contour and mass, probably undergoing frequent submergence and emergence.

That in Miocene (Late Tertiary) times it still retained its continental character, but towards the end of that period it began to disintegrate, owing to successive volcanic and other causes.

That this disintegration resulted in the formation of greater and lesser insular masses. Two of these, considerably larger in area than any of the others, were situated (a) at a relatively short distance from the entrance to the Mediterranean ; and (b) in the region of the present West India Islands. These may respectively be called Atlantis and Antillia. Communication was possible between them by an insular chain.

That these two island-continents and the connecting chain of islands persisted until late Pleistocene times, at which epoch (about 25,000 years ago, or the beginning of the Post-Glacial epoch) Atlantis seems to have experienced further disintegration. Final disaster appears to have overtaken Atlantis about 10,000 B.C. Antillia, on the other hand, seems to have survived until a much more recent period, and still persists fragmentally in the Antillean group or West India Islands.

If these data be accepted as affording proof, as substantial as in the circumstances can be expected, of the existence of Atlantis at some time within the past twelve thousand years, we may now proceed to a consideration of its exact site.

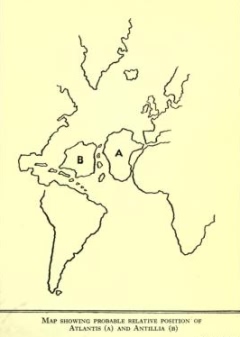

One of the most popular theories relating to the former site of Atlantis is that which gives it a coincidence of area with the Sargasso Sea. Although the Sargasso Sea is one of the most easily accessible parts of the earth's surface, one of its permanent and conspicuous features, more uncertainty respecting its actual character seems to exist than in the case of the peaks of Everest, or the Desert of Obi. That legend should be so busy concerning a large tract of the Atlantic Ocean, a floating continent of weed, lying no farther from the shores of the United States than does the Bay of Biscay from our own, is chiefly due to the popular ignorance of oceanography which prevails.

During quite recent years the most extraordinary reports have been circulated of the imprisonment in the vast fields of the Sargasso weed of flotillas of sea-going vessels ancient and modern, from the triremes of Tyre to the tramp steamer. These are, of course, gross exaggerations arising out of the persistent traditions of centuries. The Sargasso is, indeed, shunned by vessels for more reasons than one. But it is safe to say that no modern ocean-going liner could possibly become entrapped in its luxuriant masses of vegetation, did it seek to traverse them. But, as we have seen, good evidence exists that in more remote days vessels found much difficulty in navigating the Sargasso, if they were not caught within its toils.

The Sargasso Sea occupies an area of at least 3,000,000 square miles, embracing a tract extending from the 30th parallel of longitude to the Antilles, and from the 40th to the 20th parallel of latitude. This area, indeed, applies only to that portion of the sea which contains at least five per cent, of weed. But the natural region of the Sargasso, estimated not only on the occurrence of Gulf Weed, but also on the prevailing absence of currents and the relatively high temperature of the water in all depths, is at least 5,400,000 square miles, an area somewhat less than half of the continent of Europe.

The weed characteristic of this almost unique oceanic stretch belongs to the brown algae, and is named Sargassum bacciferum, more colloquially Gulf Weed. It is easily recognised by its small berry-like bladders, and is believed to be continually replenished by additional supplies torn from the North American coast by waves, and carried by currents until they accumulate in the great Atlantic whirl which surrounds the Sargasso. It is thought that the older patches gradually lose their power of floating, and perish by sinking in deep water. They become covered with white patches of polyzoa and worms living in twisted calcareous tubes, and small fishes, crabs, prawns and molluscs, inhabit the mass, all exhibiting remarkable adaptative colouring, although none of them naturally belong to the open sea.

The Arcturus expedition, under the direction of Dr. Beebe, of the New York Zoological Society, which is presently investigating these mysterious stretches of weed-encumbered ocean, some time ago dispatched a wireless message to the New York newspapers respecting the discovery of glass, volcanic rock and sponge deposits from the bed of the Sargasso. The chief purpose of the expedition is to determine whether the weed of which the Sargasso is composed is blown out from the land, or propagates itself, and to examine and photograph the strange forms of life which inhabit it.

What is certain is that the Sargasso Sea is the abode of myriads of marine creatures fishes, crustaceans, molluscs, from the probably gigantic to the infinitely small. It is the feeding-place of many species of birds. Some scientists suppose that as the upper life of this sea zone dies and falls to the bottom it must support a great and wonderful deep-sea life at various levels. These levels, to the very lowest, are now to be explored with the aid of trawls, dredges, hooks, traps and other devices. Living and dead specimens will be collected. Fish from the extreme depths, which explode when brought to the surface, will be taken out in air-pressure apparatus and kept alive in special aquarium tanks.

The present attitude of science towards the problem of the Sargasso may be summed up in the words of Lieut. J. C. Soley of the U.S. Navy, who, in his Circulation of the North Atlantic, says that the South-east branch of the Gulf Stream "runs in the direction of the Azores, where it is deflected by the cold, up welling stream from the north, and runs into the centre of the Atlantic Basin, where it is lost in the dead waters of the Sargasso Sea." Commenting on this, the U.S. Hydrographic Office observes: "Through the dynamical forces arising from the earth's rotation, which cause moving masses in the northern hemisphere to be deflected toward the right-hand side of their path, the algae that are borne by the Gulf Stream from the tropical seas find their way towards the inner edge of the circulatory drift which moves in a clockwise direction around the central part of the North Atlantic Ocean. In this central part the flow of the surface waters is not steady in any direction, and hence the floating seaweed tends to accumulate there. This accumulation is perhaps most observable in the triangular region marked out by the Azores, the Canaries and the Cape Verde Islands, but much seaweed is also found to the westward of the middle part of this region in an elongated area extending to the yoth meridian. The abundance of seaweed in the Sargasso Sea fluctuates much with the variation of the agencies which account for its presence, but this office does not possess any authentic records to show that it has ever materially impeded vessels."

It is obvious that this statement is influenced by present day conditions. If the gigantic rope-like masses of the Sargasso weed could scarcely impede the progress of modern steamers equipped with powerful screws, they may well have hampered the galley oars on which ancient and mediaeval navigators had perforce to rely in time of calm. Also it is scarcely credible that small sailing vessels could freely drive through them with an ordinary wind. As we have seen, there is a very large body of testimony that in ancient times the Atlantic was unnavigable, and that the Sargasso Sea formerly occupied a much larger area.

If the Gulf Weed was unobstructive, it is difficult fo account for the warnings and complaints of the geographical writers of antiquity. In these days, when ocean lanes and sea-ways are so narrowly laid down for steamships, and when the captains of sailing vessels have learned what areas of sea it is best to avoid, formal reports of impediment are scarcely to be expected. But there is assuredly some basis for the age-long evil repute of the Sargasso Sea.

We will recall that Plato in his Critias, speaking of the foundering of the continent of Atlantis beneath the waves, remarks that "the sea in these regions has become impassable. Vessels cannot pass there because of the sands which extend over the buried isle.' "It must be evident," says Mr. W. H. Babcock, in his Legendary Islands of the Atlantic , "that Plato would not have written thus unless he relied on the established general repute of that part of the ocean for difficulty of navigation."

Maury, writing about 1850, describes the Sargasso Sea as being "so thickly matted over with Gulf Weed that the speed of vessels passing through it is often retarded. To the eye, at a little distance, it seems substantial enough to walk upon. Patches of the weed are always to be seen floating along the edge of the Gulf Stream. Now if bits of cork, or chaff or any floating substance be put in a basin and a circular motion be given to the water, all the light substances will be found crowding together near the centre of the pool where there is the least motion, ust such a basin is the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf Stream; and the Sargasso Sea is the centre of the whirl. Columbus first found this weedy sea in his voyage of discovery; there it has remained to this day, moving up and down, and changing its position, like the calms of Cancer, according to the seasons, the storms and the winds. Exact observations as to its limits and their range, extending back for fifty years, assure us that its mean position has not been altered since that time."

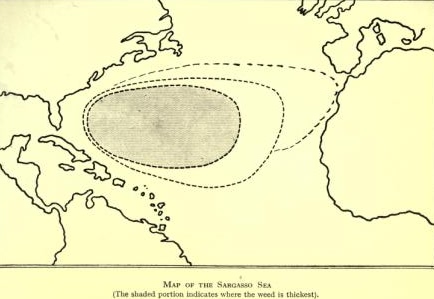

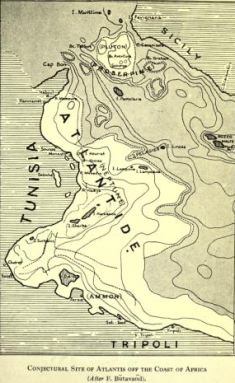

CONJECTURAL SITE OF ATLANTIS OFF THE COAST OF AFRICA (After F. Butavand).

A venerable tradition associated the Sargasso Sea with the sunken continent of Atlantis , and numerous writers have asserted their belief that in its area the former site of Plato's submerged island is to be found. However that may be, the Sargasso weed seems to have persisted for thousands of years. Weed of the same species as is found in the Sargasso occurs in the Pacific Ocean west of California, where it is known land formerly existed. That land once above water is now submerged beneath the Sargasso Sea seems apparent. The great bank mapped out by the several expeditions which undertook the survey of the Atlantic towards the latter part of last century in the Hydra, Porcupine, Challenger and Dolphin, has partial relations with the Sargasso area.

This bank commences at a point south of the coast of Ireland, is traversed by the 53rd parallel, and stretches in a direction which embraces the Azores toward the African coast. The general level of this great ridge or plateau is some 9,000 feet above that of the bed of the Atlantic. Other immense banks stretch from Iceland almost to the South American coast, where they adjoin the old sunken land of Antillia. It is precisely above the area where the great sunken plateaux converge, that is between the 4Oth and 6oth parallels of longitude, and the 2Oth and 4Oth parallels of latitude, that the Sargasso weed is thickest. There appears, too, to be good evidence that that algae propagates itself, and does not drift from the North American coasts or the Gulf Stream, as oceanographers formerly believed. But in all probability the matter will be set at rest by the report of the Arcturus expedition, the researches of which can scarcely fail to enlighten us regarding one of the most curious phenomenons of that marine world concerning the deeper mysteries of which we know so little.

It will be admitted that reliable evidence exists for the assumption that the area of the Sargasso Sea coincides with that of sunken Atlantis. A greater amount of proof that the weed of which it is composed is in some manner connected with the detritus of the sunken continent is certainly desirable. Not only does the coincidence of areas between the Sargasso and the traditional site of Atlantis assist such a hypothesis, the antiquity of the classical allusions to the Sargasso accumulation and the obviously wider area it occupied in ancient times appear to strengthen it.

We have here, of course, to consider the site of Atlantis only during that phase of its existence when it was occupied by human life. Practically all geologists are agreed, as we know, that in Miocene or late Tertiary times it still retained its continental character, occupying the whole or major part of the North Atlantic region, but many believe that it disappeared during that era. Others, to whose opinion we adhere, think that towards the end of the period in question, it began to disintegrate, owing to volcanic and seismic causes. This disintegration, as we think, resulted in the formation of the islands of Atlantis and Antillia. We can, for the present, leave the latter out of our considerations. What, exactly, was the geographical position and site of the island known as Atlantis, at the period when its early population, the Cro-Magnon Race, began to leave it for European soil?

The island, says Plato, (1) was situated in front of the Pillars of Hercules, otherwise the Straits of Gibraltar; (2) It was greater than Libya (the Greek name for Mediterranean Africa) and Asia (Asia Minor only in Plato's time) combined. This would give it an area, roughly, of about 2,650,000 square miles, or some 350,000 miles less than Australia. Supposing it to have lain, as Plato says, directly in front of, and at no great distance from, the Hispano-African coasts (as the fact that part of it was called "Gadiric," implies) then we must think of a land-mass which extended westward at least to the 45th parallel of longitude, and from north to south, nearly from the 45th parallel of latitude to about the 22nd parallel of latitude, as shown on the accompanying map. This area embraces not only the Azores and the Canary Islands, but much of the Sargasso Sea as well, though not its thickest part, and lies directly above the great banks surrounding the Azores and the Canaries. If we regard the Canaries as its south-eastern extremity (and it could not have come much farther in this direction without touching the African coast), and the Azores as the northern limit of the Atlantean land-mass proper at the period in question, and prolong it westward towards the 45th parallel of longitude, we have not only an area commensurate with that mentioned by Plato, but with those natural features which strikingly demonstrate its former presence. It seems probable, too, that the original area of Atlantis may have coincided with that of the whole area of the Sargasso Sea. This, of course, refers, as I have said, to the "last phase " of Atlantis, from 23,000 B.C. to about 9600 B.C., when it became finally submerged, according to Plato. Naturally it may have undergone some shrinkage during that period, as it certainly had during the period antecedent, but surely Plato must have had at his disposal some information of a very definite character to permit him to make a statement so clearly in accord, as I have shown, with the natural features of the Atlantic basin, submarine and supermarine. It does not seem to me that Mr. W. Scott-Elliot, in his interesting book, The Story of Atlantis, or M. Gattefosse" in his La Verite sur UAtlantide, have taken these features sufficiently into consideration along with Plato 's account in framing the excellent maps which accompany their arguments. The last phase of Atlantis, Poseidonius, as shown by Mr. Scott-Elliot's map, is a world away from the Hispano-African coast, as, allowing for the former existence of the African "shelf" and for Plato's statement, it could not possibly have been, and the same applies to M. Gattefosse"'s conjectural map of Atlantis in Tertiary times. If the island-continent lay, " before the mouth of the strait," as Plato says, and the quicksands left by its submergence hindered navigation at the very mouth of the strait, as Aristotle and Scylax of Caryanda assert, the island which caused the debris must logically have been in close proximity to the Straits of Gibraltar.

The conjectural map of Bory de St. Vincent, which was compiled not only from Plato's account, but from that of Diodorus Siculus, appears more in consonance with the facts as given by these authors, but I think it should certainly have shown Atlantis as extending farther northward, so as to face the straits of Gibraltar, and come more "under Mount Atlas," as Diodorus states it did. Moreover it shows no proximity to the "Gadiric" region of Spain.

MAP SHOWING POSITION OF ATLANTIS ACCORDING TO SCOTT ELLIOT

The latest theory regarding the site of Atlantis is that of M. F. Butavand, as given in his La Veritable Histoire de Atlantide (Paris, 1925). He believes that Atlantis was situated inside the Straits of Gibraltar, and that it was, indeed, a portion of the ancient coast of what is now Tunis and Tripoli. He thinks that the "sea" alluded to by Plato as having been opposite Atlantis was the Tyrrhenian Sea, and casts doubts on Plato's chronology. The arguments hydraulic and oceanographic with which he buttresses his theory are as remarkable as they are ingenious, and he identifies several islands now existing off the sunken coast of Tripoli with those alluded to by Proclus, in his commentary on the Timceus, as having been contiguous to Atlantis. He adduces proof that this part of the Mediterranean was particularly difficult of navigation, and argues that it must have been this especial locality which was so alluded to by the Priest of Sais. He further brings philological evidence to his aid, and manages to involve with his thesis the story of the Israelites crossing the Red Sea! Interesting and ingenious as is his essay, however, one must regard it as scarcely designed to contribute to the lucidity of Atlantean study.

And in what circumstances did the Atlantic Ocean come to bear the name of Atlas? Did it not do so because the traditions of Atlantis, the island-continent which had once occupied a considerable portion of it, survived into historic times? Atlantis is the genitive or possessive form of Atlas, meaning "of Atlas," and "Atlantic" is merely the adjective thereof. The handiest dictionary renders it as "pertaining to Atlas." Skeat derives it as "named after Mount Atlas . . . from crude form Atlanti." The name Atlas means "the sustainer, or bearer," from the Sanskrit root Tal, "to bear." But there is always a "but" in these matters it seems extraordinary that the island of Atalanta, near Eubcea, the largest island of the Agean Sea, had a history somewhat resembling that of Atlantis. Strabo in his First Book (3. 20.) says: "And they say, also, of the Atalanta near Eubcea, that its middle portions, because they had been rent asunder, got a ship-canal through the rent, and that some of the plains were overflowed even as far as twenty stadia, and that a trireme was lifted out of the docks and cast over the wall." Diodorus Siculus says that Atalanta was once a peninsula, and that it was broken away from the mainland by an earthquake. Now both writers obviously refer to an earthquake which occurred in 426 B.C., or the year before Plato's birth. Plato must, therefore, have known of the occurrence. There was also a tradition in the neighbouring island of Eubcea that that place had been separated from Boeotia by an earthquake.

"The epithet Atlantic," says Dr. Smith in his Classical Dictionary, was applied to it from the mythical position of Atlas being upon its shores." That means it was called after the god or Titan Atlas. But at what date was it first so called? Homer alludes to it as " Oceanus." Plato himself calls it "Atlantic," as if it were a name with which he was well acquainted.

We may then conclude that the island-continent of Atlantis at the time of its submergence extended from a point close to the entrance to the Mediterranean to the 45th parallel of longitude, and from north to south, nearly from the 45th parallel of latitude to about the 22nd parallel of latitude.