|

|

History of Atlantis by Lewis Spence

Index | Chapter: 1 | 2 |3 | 4 |5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |9 | 10 |11 | 12 |13 | 14 |15 | 16

CHAPTER XVI.

THE ATLANTEAN CULTURE COMPLEX

WE find then that the old belief that the great power of Atlantis founded something in the nature of ready-made colonies in Egypt, North Africa, America, and elsewhere, must give way to the much more sane and reasonable hypothesis that a species of slow cultural penetration drifted eastward and westward from the area of the now submerged continent. It is, indeed, extremely improbable that Atlantis actually founded anything in the nature of a colony. It is much more likely that the Atlantean influence, after gaining a footing on the shores of Europe, America and Africa, slowly skirted these and finally penetrated some little distance into their interiors. Indeed it is on the coast-lines of these continents that we discover the best evidences of what may be termed Atlantean influence.

Every great civilization has been distinguished by a very definite group of cultural and customary manifestations and practices, and the proof that the Atlantean civilisation was so distinguished is fairly evident. From the shores of western Europe to those of eastern America a certain culture-complex is distributed and is found on the intervening insular localities, while its manifestations are also to be discovered in great measure in North Africa and Egypt on the one hand, and in Mexico, Central America and Peru on the other. This culture-complex is so constant in the region alluded to that it is clear now that a lost oceanic link formerly united its American and European extremities.

The principal elements which distinguished the Atlantean culture-complex are the practice of mummification, the practice. of witchcraft, the presence of the pyramid, head-flattening, the couvade, the use of three-pointed stones, the existence of certain definite traditions of cataclysm, and several other minor cultural and traditional evidences. The main argument is that these are all to be found collectively confined within an area stretching from the western coasts of Europe to the eastern shores of America, and embracing the western European islands and the Antilles. So far as I am aware, these elements are not to be found associated with each other in any other part of the world. This seems to supply the surest kind of proof that they must have emanated from some Atlantic area now submerged, which formerly acted as a link between east and west, and whence these customs were distributed eastward and westward respectively.

We have seen that the ancient Aurignacians of Spain and France possessed the rudiments of the art of mummification, and it is also well-known that their kindred on the Canary islands were acquainted with it in its more advanced stage. From the work of Alonzo de Espinosa, a friar of the sixteenth century, we learn that in these islands there existed a caste of embalmers who, like those of the Nile country, were regarded as outcasts. The corpse was embalmed with a mixture of melted mutton-grease and grass-seed, stones and the bark of pine-trees, the object being to give the shrunken frame the contours of life. The body was then placed in the sun until it was dried, and was later sewn up in sheepskin, which was then enclosed in pine-bark. Some of the more distinguished dead were placed in sarcophagi made of hard wood and carved in one piece in the shape of the body, precisely as were the Egyptian mummy-cases. It is also known that dressed skins were swathed round the body just as linen bands were wound round the Egyptian corpse. The Canarese custom further resembles the Egyptian in that the first incision in the body was made with a stone knife. Examination of the mummies found in the Canary Islands prove them to bear a close resemblance to those of Peru.

The beginnings of mummification are thus found among the Aurignacians of Spain and France, and its later stage among the people of the Canary Islands. If we cross the ocean to the Antilles, we find that the art of mummification had at one time flourished there. In Porto Rico the skull and bones of the dead were wrapped in cotton cloth or in baskets and preserved for worship. Again the skulls were frequently attached to false bodies made of cotton and were kept in a separate temple. The Caribs likewise made cotton images which contained human bones. Peter Martyr alludes to certain zemis or idols made of cotton, and one of these, discovered in Santo Domingo, consisted of a skull enclosed in a cotton covering and mounted on a body stuffed with the same material. Artificial eyes had been inserted in the eye-sockets and cotton bandages tied round the legs and arms. In Haiti it was the practice, before interring the body, to bind it with bandages of woven cloth and to place it in a grave with symbols and amulets. Las Casas and Columbus both mention that the Indians of Haiti made statues of wood in which they placed the bones of relatives, giving the statues the names of the people to whom the bones belonged. One myth of the Haitian Indians told how a certain idol, Faraguvaol, was, like the mummified Osiris, discovered in the trunk of a tree. When wrapped in cotton he was able to escape from it as the Egyptian ba or soul could escape from its mummy-swathings.

Mr. J. H. Fewkes, who has investigated the native customs of the Antilles, remarks that: "The dead were sometimes wrapped in cotton cloth, and cotton puppets or effigies of stuffed cotton cloth in which the bones of the dead were wrapped are mentioned in early writings. One of the best of these is figured in an article by the author in his pamphlet on zemis from Santo Domingo. . . . The figure, which was found, according to Dr. Cronau, in a cave in the neighbourhood of Maniel, west of the capital, measures 75 centimetres in height. According to the same author the head of this specimen was a skull with artificial eyes and covered with woven cotton. About the upper arms and thighs are found woven fabrics, probably of cotton, following a custom to which attention has been already called. There is a representation of bands over the forehead." Here we see a distinct reminiscence of mummy bandaging, and a great gap in the abdomen of the figure conclusively shows that the intention of the maker was to represent an eviscerated corpse.

If now we proceed further westward to the mainland of America we find abundant evidence of the practice of embalming the dead. This is, of course, more apparent in the highly civilised centres such as Mexico, Central America and Peru. The method of embalming the body differed in these several regions. In Mexico it was placed in a sedentary position inside a mummy-bundle, which was covered with embroidery, feathers and symbols. Over this was placed a network of rope, and on the top was placed a false head or mask, which provides a link with the practice of the Antilles. In Central America the body after embalment was disposed in a recumbent attitude and swathed round with bandages, almost as in Egypt. The pictures in the Mexican and Maya native manuscripts provide many representations of mummies. The Maya of Central America buried the bodies of kings and priests in elaborate sarcophagi of stone, accompanying them with canopic vessels similar to those employed in Egyptian funerary practice, and covered by lids representing the genii of the four parts of the compass, as was also the case in Egypt.

Like the Egyptians, too, the Maya associated certain colours with the principal bodily organs and with the cardinal points. In some cases colours and organs affected agree both as regards their Maya and Egyptian examples. We also find the dog regarded as the guide of the dead both in Egypt and Mexico. When a Mexican chieftain died a dog was slain, which was supposed to precede him to the other world, precisely as the dog Anubis did in the case of the dead Egyptian. A further striking similarity between Mexican and Egyptian funerary practice is the presence in Mexican manuscripts of the tat symbol in association with the mummy, the emblem which was believed to provide the dead with a new backbone on resurrection. This tat symbol, it may be said in passing, bears a strong resemblance to certain of the Azilian symbols found on painted pebbles and in caves in France and Spain .

Certain Mexican gods were actually developed from the idea of the mummy. One of them, Tlauizcalpan-tecutli, the god of the planet Venus, is shown both in the Codex Borgia and the Codex Borbonicus as a mummy accompanied by the small blue dog, the companion of the dead. On the recurrence of his festival a mock mummy-bundle was raised upon a mast, round which the celebrant priests danced. Perhaps the most instructive picture among the Mexican manuscripts in relation to this subject is that in the Sahagun MS., in which Mexican priests are depicted in the act of manufacturing the sham mummy, the mask, the paper ornaments and flags which accompanied it. Almost equally interesting is the Relation de las ceremoniosy Ritos de Michoacan, quoted by Seler, which contain a number of striking pictures illustrating the process of mummification in that region.

In Peru the art of mummification was widespread and the tombs of that country have furnished large numbers of mummied bodies. The dead were wrapped in llama skins, on which the outline of the eyes and mouth were carefully marked. In many other parts of America mummification was practised, but as I have already dealt with the whole evidence for this at very great length elsewhere, it would be a work of supererogation to detail it in this place.

The second distinguishing element of the Atlantean culture-complex is the presence of witchcraft. It is not intended to convey the impression that witchcraft is not found in countries to which this culture-complex does not penetrate, the intention being to show that where it is discovered in connection with the other elements of the complex Atlantean culture had penetrated. In fact it seems probable that witchcraft, as a cult, originated in Atlantis. It is indeed a fertility cult, originating in a very early worship of the bull as a symbol of animal fertility, but what makes it of the greatest significance for the student of Atlantean Archaeology is the fact that in its most striking aspects it is associated with those regions which were undoubtedly most affected by immigration from Atlantis France, Spain and Mexico, and in the Aurignacian area of the two former countries. Its distribution in fact is much the same as that of the early customs which later developed into mummification.

That the Aurignacians practised it, we have the best evidence from their wall-paintings. In a rock-shelter at Cogul, near Lerida, in Spain, a painting has been discovered which represents a number of women dressed in the traditional costume of witches, with peaked hats and skirts descending from the waist, dancing round a male idol or priest, who is painted black the "black man," indeed, of witch tradition. The scene is representative of a witches' sabbath. That the witch-cult also flourished in Mexico before and after its invasion by Cortes, is well-known. The Mexican witches, the ciuateteo, were supposed to wander through the air, to haunt cross-roads, to afflict children with paralysis, and to use as their weapons the elf-arrows, precisely as did the witches of Europe. The witches' sabbath was indeed quite as notorious an institution in ancient Mexico as in mediaeval Europe. The Mexican witch, like her European sister, carried a broom on which she rode through the air, and was associated with the screech-owl. Indeed the queen of the witches, Tlazolteotl, is depicted as riding on a broom and as wearing the witch's peaked hat. Elsewhere she is seen standing beside a house accompanied by an owl, the whole representing the witch's dwelling, with medicinal herbs hanging from the eaves. The Mexican witches, too, like their European counterparts, smeared themselves with ointment which enabled them to fly through the air, and engaged in wild and lascivious dances, precisely as did the adherents of the cult in Europe. Indeed the old Spanish friars who describe them call them witches.

The connection between mummification and witch-craft is sufficiently clear, for the witches of Europe prized above all things a piece of Egyptian mummy-flesh as a vehicle for their magical operations, and the same practice was in vogue in America, where the hands and fingers of dead women were employed by the sorcerer for magical purposes. Moreover the Kwakiutl wizards of North-West America employed as a magical vehicle the skin and flesh of a dead man dried and roasted before the fire, and rubbed and pounded together.

This was then tied up in a piece of skin or cloth and squeezed into a hollow human bone, which was buried in the ground in a miniature coffin. The relationship between European and American witchcraft is thus sufficiently clear, nor does either system show any great degree of resemblance to the sorcery cults of Asia, most of which are essentially male organisations. These similarities, when considered along with the geographical occurrence of the cult, appear much too significant to be ignored, especially when it is borne in mind that the ancient Aurignacian area was in later times one of the strongholds of witchcraft in Europe. It would seem, too, that we have the very best possible reasons for regarding witchcraft in Europe and America as an emanation from Atlantis. In the Greek mythological tales of the Gardens of the Hesperides and of the Amazons of Hesperia, we find memories of a well-marked female cult, just as we do in the traditions of the Guanches of the Canary Islands, the last remnants of Atlantis. I have already summarized the traditional material connected with the Amazons and their invasion of Atlantis, from which it seems clear that they had a distinct association with witchcraft. They were, in short, a female cult of warlike tendencies and perhaps of cannibalistic leanings, like the more modern Amazons of Dahomey. It is significant, too, that we find the witches of Mexico behaving in precisely the same manner as the Amazons of classical tradition. In fact at one period in Mexican history a large force of Amazons or women warriors dwelling in the Huaxtec region on the Eastern coast of Mexico invaded the Mexican valley. They sacrificed their prisoners of war, and it is noteworthy that their leader on that occasion was Tlazolteotl, the chief goddess of the witches. Their principal weapon, like that of the Amazons, was the bow, and it is clear from Camargo's account of their patron goddess that she came from the classical Gardens of the Hesperides. He says that she " dwelt in a very pleasant and delectable place, where are many delightful fountains, brooks, and flower-gardens, which are called Tamoanchan, or the Place where are the Flowers, the nine-fold enchained, the place of the fresh, cool winds." This passage obviously connects the Amazons of Hesperia with those of Mexico, and the circumstance that both were armed with the bow, and the serpent-skin shield seems to clinch the matter.

Witch cults were also to be found on the European and American islands which formed links in the chain between Atlantis and the respective mainlands. Among the Guanches of the Canary Islands was found a sect known as the Effenecs, whose virgin priestesses, the Magades, worshipped in stone circles. On the Barranco of Valeron the circle in which they celebrated their rites still stands. Like the Mexicans, Aurignacians and Cretans, they engaged in symbolic dances and cast themselves into the ocean as a sacrifice to the waters which they believed would one day submerge their islands. Like the priestesses of the Mexican Tlazolteotl, too, it was their duty to baptise infants. Polyandry was in vogue among them, and it would seem that feminine rule obtained in the island. In the Antilles it is a little difficult to disentangle the native elements of witchcraft from those of the cult of Obeah, which is of African origin, but the distinct presence in these islands of priestesses of that cult shows that it must also have had a strong hold in that area.

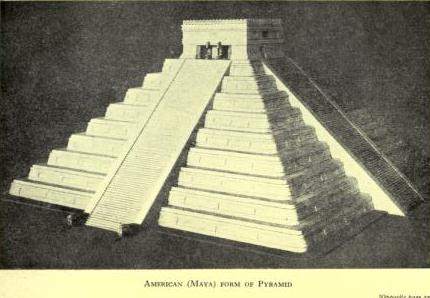

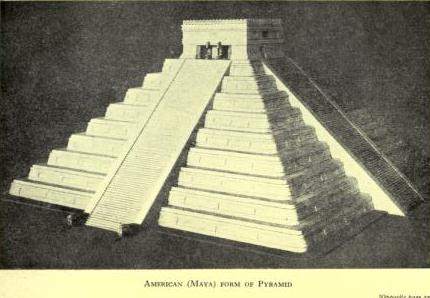

The presence of the pyramid is a further evidence of the presence of the Atlantean complex. The evidence for this has already been referred to, and it is only necessary to say here that pyramids, either of a fully developed character or in an evolutionary form, are found closely associated with the other elements of the Atlantean culture-complex in Europe, as in the Canary Islands (in dolmen form), in the Antilles and in Mexico and Peru, as well as in the region of the Mound-builders in the Mississippi country. But we arrive now at evidence of a still more remarkable character.

The custom of flattening the head artificially is one so very peculiar that it cannot be regarded as having originated in more than one distinct area, yet we find it indubitably associated with the other elements of the Atlantean complex, whilst we do not discover it in other parts of the world to which that complex did not penetrate. Thus we discern it very clearly in the Aurignacian figures depicted in the marvellous wall-painting at Alpera, among the natives of Biscay at the present day, in the Antilles, and among the Maya and Aztecs of Central America. This type of cranial distortion seems indeed to have been a part of the specific culture which spread along the Atlantic route from Biscay to Central America. Sir Daniel Wilson remarks that Dr. Foville, "a distinguished French physician at the head of the Asylum for the Insane in the department of Seine-Inferieure and Charenton, has brought to light the remarkable fact that the practice of distorting the skull in infancy still prevails in France, by means of a peculiar head-dress and bandages; and in his large work on the Anatomy of the nervous system he has engraved examples of such compressed heads, one of which might be mistaken for a Peruvian sepulchral relic. The practice is probably one inherited from times of remote antiquity, and is found chiefly to characterise certain districts. Normandy, Gascony, Limousin and Brittany are specially noted for its prevalence, with some local variations as to its method and results." It is also well known that deformation of the cranium is to-day widely practised by the Basques, who occupy almost the same territory as did the Cro-Magnons in Aurignacian times.

This custom of head -distortion is also practised among the Indians of the Antilles, of whom Charlevoix says;

"They flattened their heads by art, thus reducing the size of their forehead, which pleased them greatly. To do this their mothers took care to hold them tightly pressed between their hands or between two little boards, which by degrees flattened the head, whereby the skull hardened in a moulded shape."

Now it is a well-known fact that head-flattening by means of what is known as the cradle-board was, and is, still practised among several of the tribes of the American mainland. The Maya in especial applied pressure during infancy to the forehead, as can be seen by the sloping crania of the figures depicted in their statues and basreliefs, and the same holds good of several of the Indian peoples of the western coast of America. I cannot find traces of any practice of the kind in the Canary Islands, and it is possible that it may have died out there, but it is not a little strange to discover a custom so pronounced precisely in the line assumed for the dissemination of Atlantean culture both eastward and westward, a practice which is by no means common in other parts of the world.

It would seem, too, that the practice of tattooing the body must be associated with the Atlantean complex.

The persistent custom of tattooing, still so prevalent among our seafaring and labouring classes, has been regarded by more than one antiquary as a relic of that remote past when, in all probability, the entire population of the British islands was so decorated. That tattooing was considered by the Romans as a practice peculiarly British is manifest from many classical passages, but especially in one from Claudian, who personifies Brittania as a female whose head is crowned with the skin of a "Caledonian monster/' and whose cheeks are heavily marked with the imprints of the tattooing iron. Herodian, a Greek contemporary of Severus, is our authority for the statement that the northern Britons, whom that general encountered in his campaign, did not wear garments because they did not wish to conceal the tattoo designs with which their bodies were covered.

Ample proof is, indeed, forthcoming that the tribal name "Britons" signified the "tattooed people." The Goidelic or Gaelic-speaking inhabitants of the British Isles called themselves "Cruithne" or "Qrtanoi," "those who tattoo themselves." This word, in the mouths of the Kymric-speaking sailors of Marseilles, who carried merchandise to and from Briton, became "Brtanoi," and in those of the Greek merchants of that town, Bretanoi, thus for ever associating our national designation with a foreign mispronunciation. To the Welsh, another Kymric-speaking people, Pictland was known as "Priten," and at an early era there is proof that they gave this name to the whole island, "Ynys Prydain," or "The Picts Island," that is "The Island of the Tattooed People."

That "Cruithne" or "Qrtanoi" signified "Tattooed " is clear enough from another passage in Herodian, who says that the Northern Britons tattooed upon their skins the figures of animals. This notice of the practice is doubly valuable, as it was written at least a century before the name of the Picts or tattooed people is mentioned in classical literature. It is upheld by a rendering of the early Gaelic writer Duald MacFirbis, who says that "Cruithneach (Pictus) is one who takes the cruths or forms of beasts, birds and fishes on his visage, and on his whole body."

This evidence, it will be seen, is entirely apart from those older derivations which drew the name "Pict" from the Latin pictus, "painted." But that the name Pict, in its native, and not in its Latin form, meant "tattooed" is certain. It goes back to an old Goidelic form Qict, and to a much more ancient Aryan root peik, signifying "tattooed," and that the word naturally became confused by the Romans with their own term pictus admits of no doubt. Claudius's oft-quoted statement that the Picts were "nee falso nomine Pictos," "not wrongly called the Painted People," simply implies that he knew that they decorated their bodies with symbols, and was rather surprised to find their tribal name resemble the Latin word for a painted thing or person. "Pictos" says Rhys, "was a Celtican word of the same etymology and approximately of the same meaning as the Latin pictus. The Celticans applied it at an early date to the Picts on account of their tattooing themselves, and the Picts accepted it."

But that the word "Scot" also means "tattooed" is less generally known. Rhys believed it to come from a stem meaning 'cut," or "tattooed," in which derivation he is upheld by Macbain. A passage in Isidore of Seville explains "Scot" as "a word implying one having a painted body, on which various figures have been drawn by sharp iron and coloured stains." According to Mr. E. W. Nicholson, of the Bodleian, there seems to have been little or no real difference between "Scot" and "Pict." "There was probably no greater distinction between a 'Scot* and a "Pict*," he remarks, "than between a Saxon and an Angle: both names mean the same thing, 'Tattooed.'" Speaking of the Picts and Scots of Ireland, Professor Rhys remarked that "all Irish history goes to show that they were closely kindred communities of Cruithne, and I take it that the names Cruithne and Scots may have been originally applicable to both alike."

But evidence of the most interesting kind has preserved traces of the manner in which our ancestors actually did tattoo themselves. There were Picts in France as well as in Britain and Ireland, the Pictavi of Poitiers and Poitou, whose custom of incising figures on their skins is illustrated in their coinage. In a coin of the Unalli, who inhabited the Cotentin, a head is depicted as tattooed with the design of a short sword, the hilt on the neck and the point level with the nostrils. Mr. Nicholson drew attention to this as probably associated with the name Calgacus, that of the Caledonian chief who gave battle to the Romans at Mons Graupius, and which in its native form Calgy means "sword." Calgacus, he thinks, may have been tattooed with the figure of a sword like the warrior represented on the coin in question.

A coin of the Aulerci of Maine shows a face the cheek of which is tattooed with a circle of dots, within which is the figure of a cock perhaps the earliest representation of that bird as the national emblem of Gaul. On a coin of the Bodiocasses of Bayeux appears a face circled with tattoo dots, enclosing the latter A. Coins found in Jersey abound in similar figures representing tattooed faces. Frequently the designs are astronomical, depicting comets and other heavenly bodies. On one of the coins of the Continental Picts is a head, on the jaw of which a cross is incised, having a knob at each of its four ends. All these examples hail from the West of Gaul, and the tattoo designs they display are regarded by Nicholson as probably the distinguishing marks of a Goidelic or Gaelic-speaking population, and as distinguishing it from the Kymric Celts, who do not appear to have tattooed themselves.

It is known that these Pictish tribes, who were scattered over the area from North-West France to the Orkneys, were a sea-faring people of piratical tendencies. It was such a tribe, the Veneti, whom Julius Caesar encountered in naval warfare off the Breton shores, and who were, he tells us, assisted by their kindred in Britain. Their ships were so much larger and better found than the Roman galleys that it was only after the most desperate resistance that he succeeded in overcoming them. The coasts of North-Western France and Britain, from Cornwall to Caithness, swarmed with Cruithne or Britanni of similar type, who existed on maritime trade with each other, on fishing, and, when these failed, on plunder. These tribes, in short, were the true begetters of British maritime power, who, while Norman and Saxon were still unknown upon the sea, made voyages of hundreds of miles in vessels of considerable tonnage with sails of skin, and iron cables.

May it not be that from these hardy seafarers of the far past the maritime custom of tattooing has descended to the modern British seamen? It is noteworthy that the dress of the British sailor of Nelson's time, with its bonnet, deep collar and striped vest, is identical with the popular costume of the maritime districts of Brittany, whose sailors and fishermen are notorious tattooers. We have, of course, no evidence for the continuance of the practice during the middle ages. But it should be borne in mind that it was not then usual to record pictorially the humbler orders of society, and it is manifest that, if the custom still lingers among certain classes, it must have behind it a venerable antiquity.

So far as the origins of tattooing in Britain are concerned, it can almost certainly be traced to the ethnological association of its Celtic tribes with the Iberian race. With the Iberians the Celts mingled freely in Spain, France and Britain. It is known that the Iberians were immediately of African origin, and the ancient Egyptians put it on record that the Iberian tribes of North Africa were addicted to tattooing their bodies. Whether tattooing originated in North Africa or not, it seems probable that the custom spread thence to Asia Minor, and later to India, from where it seems to have found its way to Polynesia. However that may be, it certainly became established in Britain at an early era, so strongly, indeed, as to become the distinguishing mark of its native races, and to give its name even to the island itself.

For us, of course, "Iberian" means "Atlantean," and as tattooing in Europe certainly originated with the Iberians of Africa, it seems obvious that it must have been of Atlantean provenance. This is borne out by the fact that the Indians of the Antilles tattooed themselves in precisely the same manner as did the people of Britain and Gaul. The Guetares of Costa Rica also tattooed themselves with the figures of animals, and the Maya of Central America employed tattooing as an honorific sign, as well as head-flattening.

As we have seen, the ancient inhabitants of Spain and Gaul were tattooed. I can discover no record of the practice in the Canary Islands, but when we find the custom in vogue in three of the "links" of which Atlantis is the missing one, it would seem as though the custom of tattooing must also have emanated from the sunken continent, and have been introduced east and west along with the other features of the complex. In Britain, in particular, did it seem to linger, as doubtless it would in such an isolated area, and from that we may imply that other Atlantean imports flourished in our island until a relatively late era.

Still another custom which is of more universal adoption is to be found in connection with the Atlantean complex. This is the couvade, that strange notion, which ordains that when a child is born the father should take to his bed and there remain for days or weeks after the mother has resumed her ordinary mode of life. Diodorus Siculus assures us that it prevailed among the ancient Corsicans, and Appolonius Rhodius says that it was practised by the Iberians of northern Spain. But we find it also among the Basques of Spain and France, that is almost in the old Aurignacian region, and among the Caribs of the West Indies as well as on the South American coast. It seems to have originated in the notion that there was a spiritual union between the father and the child, and that the latter would suffer were the sire not nursed as well as the mother. It has been traced in Europe to peoples of the Mediterranean race, that is to those races who are most closely connected with the immigrant peoples of Atlantis.

A symbolical usage, which in some manner binds together the various parts of the Atlantean complex, was the belief in the thunder-stone and its strange properties. This symbol, as the elf-arrow, or in other forms, is almost universal, and is regarded not only by primitive, but by many modern peoples as the source of tempests and seismic and volcanic phenomena, whether as the bolt of Vulcan, the lance of the Carib, or the arrow of the Mexican and Egyptian deities. But in the Atlantean region it affords yet another link between the witch and mummy cults of its peculiar culture-complex. In Mexico the planet Venus, the star of Quetzalcoatl, was regarded as the thunder-stone, and this symbol in many American and West European localities was carefully wrapped in swathings of cloth or hide precisely as the mummy is wrapped. It would seem, indeed, as if the original ideas associated with it had been fostered in some seismic region, and in any case, as has been said, it links up the witch and mummy cults with the notion of seismic instability. In some of the western Irish isles tempests were precipitated by unwinding the flannel bandages in which such sacred stones were wrapped, and in Mexico the god Hurakan, the hurricane, was the southern equivalent of the god Itzilacoliuhqui, who was merely the stone-knife of sacrifice, Quetzalcoatl, in his form of the planet Venus, wrapped up in mummy bandages.

This god, like Vulcan, had been

lamed through a supernatural accident, so that he had obviously a

volcanic significance, like the god of Mount Etna, whose volcanic

scoriae were regarded as thunderbolts.

This god, like Vulcan, had been

lamed through a supernatural accident, so that he had obviously a

volcanic significance, like the god of Mount Etna, whose volcanic

scoriae were regarded as thunderbolts.

It is difficult to believe that underlying these connections there is not some original symbolism having an application to seismic activity. Probably the thunder-stone was regarded as the very germ and essence of the tempest, the magical thing which caused ebullitions of nature, winds, earthquakes or eruptions. In another of its forms it was undoubtedly regarded as an earth-shaking implement, by means of which the gods fashioned the contours of the earth. To wrap it in bandages, however, seems to have been to render it temporarily quiescent, to have made a "mummy" of it. So long as it was confined within its swathings it was symbolically "dead" and unable to function, but once these were unwound its spirit of destruction was let loose.

Archaeologists have discovered, in some parts of the Antilles, a number of strange three-cornered stones, which appear to have a close relationship with the symbol. Their geographical distribution is confined to Porto Rico, and the eastern extremity of Santo Domingo, that is to that part of the archipelago which probably formed a part of the almost vanished Antillia. These stones are usually carved in the shape of a mountain, beneath which the head and legs of a buried Titan can be observed. Says Professor Mason: "The Antilles are all of volcanic origin, as the material of our stone implements plainly shows." He proceeds to say that their shape is highly suggestive of the islands in question, and that they seem to represent mythological figures bearing the island on their backs. He points to the legend of Typheus, who was slain by Jupiter and buried under Mount Etna, and concludes: "A similar myth may have been devised in various places to account for volcanic or mountainous phenomena."

They certainly agree with the Maya conception of the Cosmos, which alludes to the earth as supported on the back of a great dragon or four-footed whale, and they appear to be associated with the myth of Atlas himself, the world-bearer connected with the story of Atlantis, and they are further reflected in the myth of Quetzalcoatl, who, in his central American form, is assuredly the dragon or serpent who dwelt in the sea. They certainly seem to me to symbolise a deity, whose duty it was to uphold the earth, but who, like Atlas, occasionally felt the immensity of his burden and cast it from him, causing universal destruction and catastrophe.

It would seem, too, that in these three-pointed stones we find a combination of the idea of Atlas and that of the world-shaping pick or hammer. Thus, in the thunder-stone symbol, it seems, the whole significance of the Atlantean culture-complex finds a nucleus. To it must be referred, as to the hub of a wheel, the practice of mummification, witchcraft, and the mysteries and art of building in stone. The hammer of the thunder-god or creative deity with which he carved and shaped the earth was indeed identical with the implement by which the early sculptor fashioned his work. Manibozho, the god of the Algonquin Indians, shaped the hills and valleys with his hammer, constructing great beaver dams and moles across the lakes. His myth says that "he carved the land and sea to his liking," precisely as Poseidon carved the island of Atlantis into alternate zones of land and water. Poseidon was notoriously a god of earthquake as well as a marine deity, and it is a fair inference that he undertook the task in question with the great primeval pick, a sharp flint beak set in a wooden haft, the mjolnir of Thor, the hammer of Ptah, by which the operation of land-moulding was undertaken in most mythologies.

It would seem that this sacred pick or hammer must have become symbolic of Poseidon in the continent of Atlantis. In all likelihood it would be kept wrapped up in linen in his temple, just as the black stone of Jupiter was preserved at Pergamos, or the arrows of Uitzilopochtli in the great temple-pyramid at Mexico. At the Kaaba at Mecca, the centre of the Mahommedan world, a similar stone is preserved wrapped up in silks, and we have seen that in the Irish islands its counterpart was swathed in flannel and preserved in a separate house.

The mythology of Mexico holds many allusions to a certain Huemac or "Great Hand," who seems to be identical with Quetzalcoatl. This figure is also found in Maya mythology as Kab-ul, the "Working Hand," a deification of the hand which wields the great pick or hammer, as is obvious in its representations in the native manuscripts. Quetzalcoatl was the skilled craftsman, the mason, who came from an Atlantic region. In his Quiche form of Tohil he is represented by a flint stone. It seems then that we have here the culture hero from a marine locality symbolised by what appears to be the central emblem of the Atlantean culture-complex. Quetzalcoatl is also the planet Venus, and this identification gives a double significance to the complex. This is by no means weakened, when we discover that this Great Hand is actually identified with Atlantis in mediaeval legends, for the map of Bianco, which dates from 1436, contains an island, the Italian name of which may be translated "the Hand of Satan." Formaleoni, an Italian writer, had observed the name, but did not appreciate its significance until he chanced to stumble on a reference to a similar name in an old Italian romance, which told how a great hand rose every day from the sea and carried off a number of the inhabitants into the ocean. The legend is undoubtedly associated with the idea of earthquake or cataclysm in a marine locality, and it seems obvious that the Great Hand was the god of this Atlantic island, who took tribute of human lives by earthquake. The story appears to link up with that of the Minotaur, the bull-deity of Poseidon, who also took toll of human lives in Crete, and with the practice of the Canary Islands, whose priestesses, as we have seen, cast themselves into the sea to placate the god of Ocean, as well as with the myth of the Titans.

In Plato's account of Atlantis practically all the details of the Atlantean complex may be discovered, and the same holds good of the myth of Quetzalcoatl. Not only do the mainlands of the two continents display the clearest traces of the presence of this culture-complex, but their advanced island-groups are eloquent of its influence. I have attempted to show that nowhere else in the world has a culture-complex embracing these particular manifestations been shown to exist. Doubtless in time it will be possible to trace many greater or less additions to this complex, but those already proven to have been associated with it should suffice to make it plain that it did actually exist and that the great likelihood is that it emanated from a now sunken region in the Atlantic.

THE END