Tutankhamen

Amenism, Atenism And Egyptian Monotheism

By E.A.W. Budge. 1923

Index | Previous | Next

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CULT OF ATEN UNDER AMENHETEP IV.

Amenhetep III was succeeded by his son by his beloved wife Ti, who came to the throne under the name of Amenhetep IV. He reigned about seventeen years, and died probably before he was thirty. The accuracy of the latter part of this statement depends upon the evidence derived from the mummy of a young man which was found in the Tomb of Queen Ti, and is generally believed to be that of Amenhetep IV. It is thought that this mummy was taken from a royal tomb at Tall al-'Amarnah in mistake for that of Ti, and transported to Thebes, where it was buried as her mummy. Dr. Elliot Smith examined the skeleton, and decided that it was that of a man 25 or 26 years of age, "without excluding the possibility that he may have been several years older." His evidence1 is very important, for he adds, "The cranium, however, exhibits in an unmistakable manner the distortion characteristic of a condition of hydrocephalus." So then if the skeleton be that of Amenhetep IV, the king suffered from water on the brain; and if he was 26 years old when he died he must have begun to reign at the age of nine or ten. But there is the possibility that he did not begin to reign until he was a few years older.

Even had his father lived, he was not the kind of man to teach his son to emulate the deeds of warrior Pharaohs like Thothmes III, and there was no great official to instruct him in the arts of war, for the long peaceful reign of Amenhetep III made the Egyptians forget that the ease and luxury which they then enjoyed had been purchased by the arduous raids and wars of their forefathers. To all intents and purposes, Ti ruled Egypt for several years after her husband's death, and the boy-king did for a time at least what his mother told him. His wife, Nefertiti, who was his father's daughter probably by a Mesopotamian woman, was no doubt chosen for him by his mother, and it is quite clear from the wall-paintings at Tall al-'Amarnah that he was very much under their influence. His nurse's husband, Ai, was a priest of Aten, and during his early years he absorbed from this group of persons the fundamentals of the cult of Aten and much knowledge of the religious beliefs of the Mitannian ladies at the Egyptian Court. These sank into his mind and fructified, with the result that he began to abominate not only Amen, the great god of Thebes, but all the old gods and goddesses of Egypt, with the exception of the solar gods of Heliopolis. In many respects these gods resembled the Aryan gods worshipped by his grandmother's people, especially Varuna, to whom, as to Ra, human sacrifices were sometimes offered, and to them his sympathy inclined. But besides this he saw, as no doubt many others saw, that the priests of Amen were usurping royal prerogatives, and by their wealth and astuteness were becoming the dominant power in the land. Even at that time the revenues of Amen could hardly be told, and the power of his priests pervaded the kingdom from Napata in the South to Syria in the North.

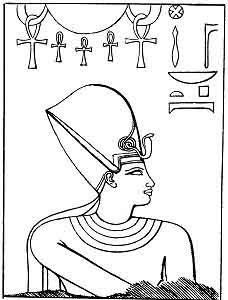

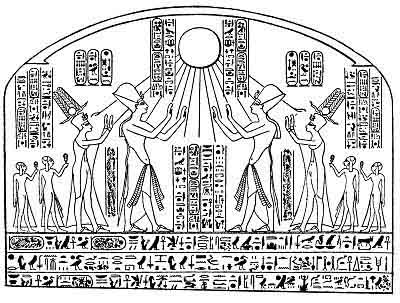

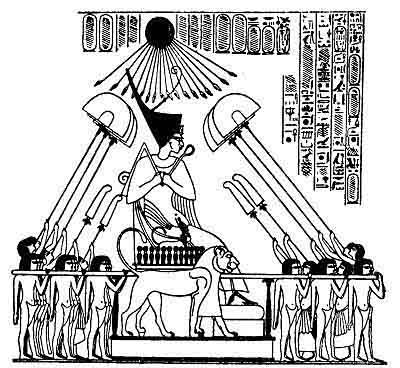

Plate VII

.Portion of a painted stone tablet with a portrait figure of Amenhetep IV in hollow relief. On him shine the rays of Aten which terminate in human hands. British Museum, No. 24431

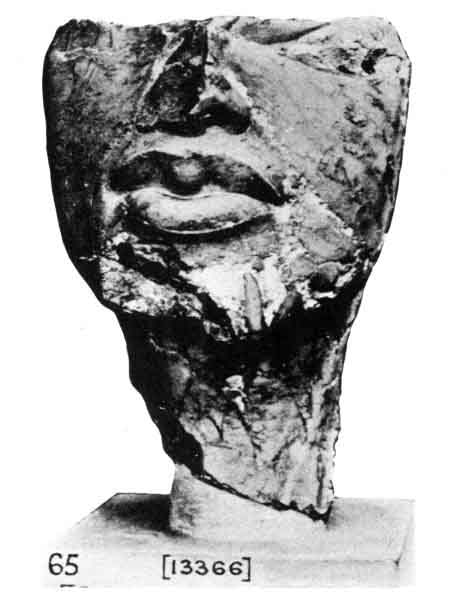

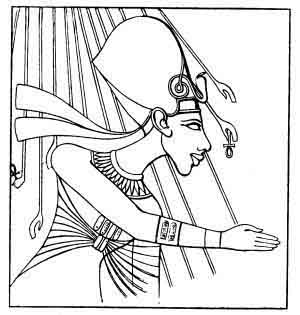

Plate VIII

.Portion of a head of a portrait figure of Amenhetep IV.

British Museum, No. 13366.

During the first five or six years of his reign Amenhetep IV, probably as the result of the skilful guidance of his mother, made little or no change in the government of the country. But his actions in the sixth and following years of his reign prove that whilst he was still a mere boy he was studying religious problems with zeal, and with more than the usual amount of boyish understanding. He must have been precocious and clever, with a mind that worked swiftly; and he possessed a determined will and very definite religious convictions and a fearless nature. It is also clear that he did not lightly brook opposition, and that he believed sincerely in the truth and honesty of his motives and actions. But with all these gifts he lacked a practical knowledge of men and things. He never realized the true nature of the duties which as king he owed to his country and people, and he never understood the realities of life. He never learnt the kingcraft of the Pharaohs, and he failed to see that only a warrior could hold what warriors had won for him. Instead of associating himself with men of action, he sat at the feet of Ai the priest, and occupied his mind with religious speculations; and so, helped by his adoring mother and kinswomen, he gradually became the courageous fanatic that the tombs and monuments of Egypt show him to have been. His physical constitution and the circumstances of his surroundings made him what he was. In recent years he has been described by such names as "great idealist," "great reformer," the "world's first revolutionist," the "first individual in human history," etc. But, in view of the known facts of history, and Dr. Elliot Smith's remarks quoted above on the distortion of the skull of Amenhetep IV, we are fully justified in wondering with Dr. Hall if the king "was not really half insane."1 None but a man half insane would have been so blind to facts as to attempt to overthrow Amen and his worship, round which the whole of the social life of the country centred.

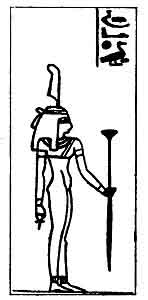

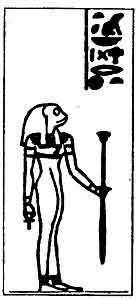

Aten, the great god, lord of heaven, from whom proceeds "life"; beneath is Amenhetep IV who is here represented conventionally as a Pharaoh.

He suffered from religious madness at least, and spiritual arrogance and self-sufficiency made him oblivious to everything except his own feelings and emotions.

Once having made up his mind that Amen and all the other "gods" of Egypt must be swept away, Amenhetep IV determined to undertake this work without delay. After years of thought he had come to the conclusion that only the solar gods, Tem, Ra and Horus of the Two Horizons were worthy of veneration, and that some form of their worship must take the place of that of Amen. The form of the Sun-god which he chose for worship was ATEN, i.e., the solar Disk, which was the abode of Tem and later of Ra of Heliopolis. But to him the Disk was not only the abode of the Sun-god, it was the god himself, who, by means of the heat and light which emanated from his own body, gave life to everything on the earth. To Aten Amenhetep ascribed the attributes of the old gods, Tem, Ra, Horus, Ptah, and even of Amen, and he proclaimed that Aten was "One" and "Alone." But this had also been proclaimed by all the priesthoods of the old gods, Tem, Khepera, Khnem, Ra, and, later, of Amen. The worshippers of every great god in Egypt had from time immemorial declared that their god was "One." "Oneness" was an attribute, it would seem, of everything that was worshipped in Egypt, just as it is in some parts of India. It is inconceivable that Amenhetep IV knew of the existence of other suns besides the sun he saw, and it was obvious that Aten, the solar disk, was one alone, and without counterpart or equal. Some light is thrown upon Amenhetep's views as to the nature of his god by the title which he gave him. This title is written within two cartouches and reads:--

"The Living Horus of the two horizons, exalted in the Eastern Horizon in his name of Shu-who-is-in-the-Disk."

It is followed by the words, "ever-living, eternal, great living Disk, he who is in the Set Festival,1 lord of the Circle (i.e., everything which the Disk shines on in every direction), lord of the Disk, lord of heaven, lord of the earth." Amenhetep IV worshipped Horus of the two horizons as the "Shu who was in the disk." If we are to regard "Shu" as an ordinary noun, we must translate it by "heat," or "heat and light," for the word has these meanings. In this case Amenhetep worshipped the solar heat, or the heat and light which were inherent in the Disk. Now, we know from the Pyramid Texts that Tem or Tem-Ra created a god and a goddess from the emanations or substance of his own body, and that they were called "Shu" and "Tefnut," the former being the heat radiated from the body of the god, and the latter the moisture. Shu and Tefnut created Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky), and they in turn produced Osiris, the god of the river Nile, Set, the god of natural decay and death, and their shadowy counterparts, Isis and Nephthys. But, if we regard "Shu" as a proper name in the title of Amenhetep's god, we get the same result, and can only assume that the king deified the heat of the sun and worshipped it as the one, eternal, creative, fructifying and life-sustaining force. The old Heliopolitan tradition made Tem or Tem-Ra, or Khepera, the creator of Aten the Disk, but this view Amenhetep IV rejected, and he asserted that the Disk was self-created and self-subsistent.

The frog-headed goddess Heqit, one of the Eight Members of the Ogdoad of Thoth.

The common symbol of the solar gods was a disk encircled by a serpent, but when Amenhetep adopted the disk as the symbol of his god, he abolished the serpent and treated the disk in a new and original fashion. From the disk, the circumference of which is sometimes hung round with symbols of "life," he made a series of rays to descend, and at the end of each ray was a hand, as if the ray was an arm, bestowing "life" on the earth. This symbol never became popular in the country, and the nation as a whole preferred to believe that the Sun-god travelled across the sky in two boats, the Sektet and the Atet. The form of the old Heliopolitan cult of the Sun-god that was evolved by Amenhetep could never have appealed to the Egyptians, for it was too philosophical in character and was probably based upon esoteric doctrines that were of foreign origin. Her and Suti, the two great overseers of the temples of Amen at Thebes, were content to follow the example of their king Amenhetep III, and bow the knee to Aten and, like other officials, to sing a hymn in his praise. But they knew the tolerant character of their master's religious views, and that outwardly at least he was a loyal follower of Amen, whose blood, according to the dogma of his priests, flowed in the king's veins. To Amenhetep III a god more or less made no difference, and he considered it quite natural that every priesthood should extol and magnify the power of its god. He was content to be a counterpart of Amen, and to receive the official worship due to him as such. But with his son it was different. The heat of Aten gave him life and maintained it in him, and whilst that was in him Aten was in him. The life of Aten was his life, and his life was Aten's life, and therefore he was Aten; his spiritual arrogance made him believe that he was an incarnation of Aten, i.e., that he was God--not a mere "god" or one of the "gods" of Egypt--and that his acts were divine. He felt therefore that he had no need to go to the temple of Amen to receive the daily supply of the "fluid of life," which not only maintained the physical powers of kings, but gave them wisdom and understanding to rule their country. Still less would he allow the high priest of Amen to act as his vicar. Finally he determined that Amen and the gods must be done away and all the dogmas and doctrines of their priesthoods abolished, and that Aten must be proclaimed the One, self-created, self-subsisting, self-existing god, whose son and deputy he was.

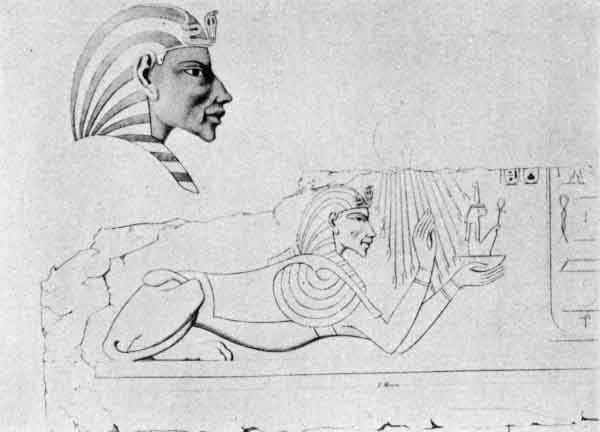

Plate IX.

Sphinx, with the head of Amenhetep IV, making an offering of Maat to Aten.

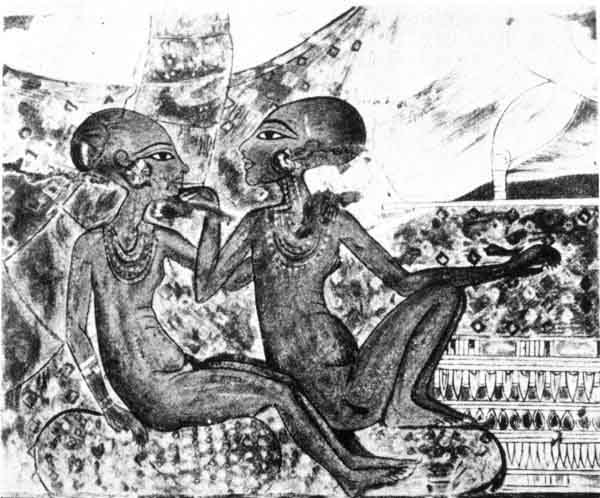

Plate X.

Two of the daughters of Amenhetep IV.

Reproduced by permission of the Egyptian Exploration Society.

From a bas-relief now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Without, apparently, considering the probable effect of his decision when translated into action, he began to build the temple of Gem-Aten in Per-Aten, at Thebes. In it was a chamber or shrine, in which the ben, or benben, i.e., the "Sun-stone," was placed, and in doing this he followed the example of the priests of Heliopolis. The site he selected for this temple was a piece of ground about half way between the Temple of Karnak and the Temple of Luxor. He decided that this temple should be the centre of the worship of Aten, which should henceforward be the one religion of his country. The effect of the king's action on the priests of Amen and the people of Thebes can be easily imagined when we remember that with the downfall of Amen their means of livelihood disappeared. But Amenhetep was the king, the blood of the Sun-god was in his veins, and Pharaoh was the master and owner of all Egypt, and of every person and thing in it. Priests and people were alike unable to resist his will, and, though they cursed Aten and his fanatical devotee, they could not prevent the confiscation of the revenues of Amen and the abolition of his services. Not content with this, Amenhetep caused the name of Amen to be obliterated on the monuments, and in some cases even his father's name, and the word for "gods" was frequently cut out. Not only was there to be no Amen, but there were to be no gods; Aten was the only god that was to be worshipped.

The result of the promulgation of this decree can be easily imagined. Thebes became filled with the murmurings of all classes of the followers of Amen, and when the temple of Aten was finished, and the worship of the new god was inaugurated, these murmurings were changed to threats and curses, and disputes between the Amenites and Atenites filled the city. What exactly happened is not known and never will be known, but the result of the confusion and uproar was that Amenhetep IV found residence in Thebes impossible, and he determined to leave it, and to remove the Court elsewhere. Whether he was driven to take this step through f ear for the personal safety of himself and his family, or whether he wished still further to insult and injure Amen and his priesthood, cannot be said, but the reason that induced him to abandon his capital city and to destroy its importance as such must have been very strong and urgent. Having decided to leave Thebes he sought for a site for his new capital, which he intended to make a City of God, and found it in the north, at a place which is about 160 miles to the south of Cairo and 50 miles to the north of Asyut. At this point the hills on the east bank of the Nile enclose a sort of plain which is covered with fine yellow sand. The soil was virgin, and had never been defiled with temples or other buildings connected with the gods of Egypt whom Amenhetep IV hated, and the plain itself was eminently suitable for the site of a town, for its surface was unbroken by hills or reefs of limestone or sandstone. This plain is nearly three miles from the Nile in its widest part and is about five miles in length. The plain on the other side of the river, which extended from the Nile to the western hills, was very much larger than that on the east bank, and was also included by the king in the area of his new capital. He set up large stelæ on the borders of it to mark the limits of the territory of Aten, and had inscriptions cut upon them stating this fact.

We have already seen that Amenhetep IV had, whenever possible,

caused the name of Amen to be chiselled out from stelæ,

statues, and other monuments, and even from his father's

cartouches, whilst at the same time the name of Amen formed part

of his name as the son of Ra. It was easy to remedy this

inconsistency, and he did so by changing his name from Amenhetep,

which means "Amen is content," to AAKHUNATEN, ![]() a name which by analogy should mean

something like "Aten is content." This meaning has already been

suggested by more than one Egyptologist, but there is still a

good deal to be said for keeping the old translation, "Spirit of

Aten." I transcribe the new name of Amenhetep IV, Aakhunaten, not

with any wish to add another to the many transliterations that

have been proposed for it, but because it represents with

considerable accuracy the hieroglyphs. The Pyramid Texts show

that the phonetic value of

a name which by analogy should mean

something like "Aten is content." This meaning has already been

suggested by more than one Egyptologist, but there is still a

good deal to be said for keeping the old translation, "Spirit of

Aten." I transcribe the new name of Amenhetep IV, Aakhunaten, not

with any wish to add another to the many transliterations that

have been proposed for it, but because it represents with

considerable accuracy the hieroglyphs. The Pyramid Texts show

that the phonetic value of ![]() was

was ![]() or

or ![]() . The first sign represents a short vowel,

a, e, or i; the second a, like the Hebrew aleph, the third

kh, and the fourth u; therefore the phonetic value

of in Pyramid times was aakh, or aakhu, but in later times the

a was probably dropped, and then the value of

. The first sign represents a short vowel,

a, e, or i; the second a, like the Hebrew aleph, the third

kh, and the fourth u; therefore the phonetic value

of in Pyramid times was aakh, or aakhu, but in later times the

a was probably dropped, and then the value of ![]() would be akh, as

Birch read it sixty years ago. If this were so, the name will be

correctly transliterated by "Akhenaten." How the name was

pronounced we do not know and never shall know, but there is no

good ground for thinking that "Ikhnaton" or "Ikh-en-aton"

represents the correct pronunciation. In passing we may note that Aten has

nothing to do with the Semitic 'adhon, "lord."

would be akh, as

Birch read it sixty years ago. If this were so, the name will be

correctly transliterated by "Akhenaten." How the name was

pronounced we do not know and never shall know, but there is no

good ground for thinking that "Ikhnaton" or "Ikh-en-aton"

represents the correct pronunciation. In passing we may note that Aten has

nothing to do with the Semitic 'adhon, "lord."

At this time Amenhetep IV adopted two titles in connection with his new name, i.e., "Ankh-em-Maat" and "Aa-em-aha-f," the former meaning, "Living in Truth" and the latter "great in his life period."

What is meant exactly by "living in truth" is not clear. Maat means what is straight, true, real, law, both physical and moral, the truth, reality, etc. He can hardly have meant "living in or by the law," for he was a law to himself, but he may have meant that in Atenism he had found the truth or the "real" thing, and that all else in religion was a phantom, a sham. Aten lived in maat, or in truth and reality, and the king, having the essence of Aten in him, did the same. The exact meaning which Amenhetep IV attached to the other title, "great in his life-period," is also not clear. He, as was every Pharaoh who preceded him, was a "son of Ra," but he did not claim, as they did, to "live like Ra for ever," and only asserted that his life-period was great. Amenhetep IV called his new capital Aakhutaten, i.e., "the Horizon of Aten," and he and his followers regarded it as the one place in which Aten was to be found. It was to them the visible symbol of the splendour and benevolence and love of the god, the sight of it rejoiced the hearts of all beholders, and its loveliness, they declared, was beyond compare. It was to them what Babylon was to the Babylonians, Jerusalem to the Hebrews, and Makkah to the Arabs; to live there and to behold the king, who was Aten's own son, bathed in the many-handed, life-giving rays of Aten, was to enjoy a foretaste of heaven, though none of the writers of the hymns to Aten deign to tell us what the heaven to which they refer so glibly was like. Having taken up his a ode in this city, Amenhetep set to work to organize the cult of Aten, and to promulgate his doctrine, which, like all writers of moral and religious aphorisms, he called his "Teaching," Sbait.

Having appointed himself High Priest, he, curiously enough, adopted the old title of the High Priest of Heliopolis and called himself "Ur-maa," i.e., the "Great Seer." But he did not at the same time institute the old semi-magical rites and ceremonies which the holders of the title in Heliopolis performed. He did not hold the office very long, but transferred it to Merira, one of his loyal followers.

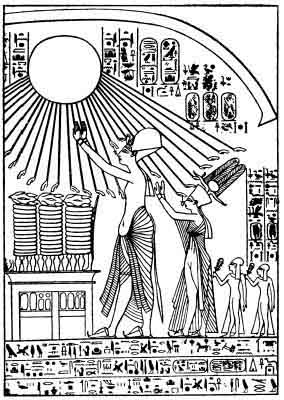

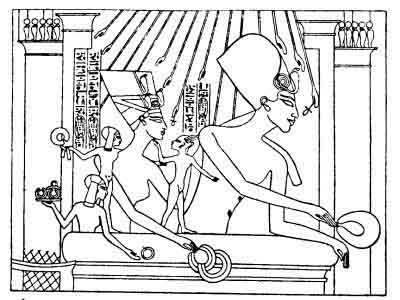

Amenhetep IV, accompanied by his queen and family, making offerings to Aten.

When still a mere boy, probably before he ascended the throne and rejected his name of Amenhetep, he seems to have dreamed of building temples to Aten, and so when he took up his residence in his new city he at once set to work to build a sanctuary for that god. Among his devoted followers was one Bek, an architect and master builder, who claims to have been a pupil of the king, and who was undoubtedly a man of great skill and taste. Him the king sent to Sun, the Syene of the Greek writers, to obtain stone for the temple of Aten, and there is reason to think that, when the building was finished, its walls were most beautifully decorated with sculptures and pictures painted in bright colours. A second temple to Aten was built for the Queen-mother Ti, and a third for the princess Baktenaten, one of her daughters; and we should expect that one or more temples were built in the western half of the city across the Nile. With the revenues filched from Amen Aakhunaten built several temples to Aten in the course of his reign. Thus he founded Per-gem-Aten in Nubia at a place in the Third Cataract; Gem-pa-Aten em. Per-Aten at Thebes; Aakhutaten in Southern Anu (Hermonthis); the House of Aten in Memphis; and Res-Ra-em-Anu.

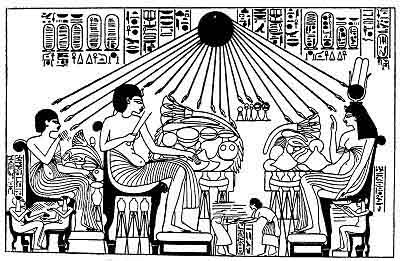

Amenhetep IV and his queen and family worshipping Aten.

al-'Amarnah tablets in the British Museum under the form Hi-na-tu-na.1.

It will be noticed that no mention is made of Aten in the name of this last temple of Aten. He also built a temple to Aten in Syria, which is mentioned on one of the Tall

Amenhetep IV and his Queen Nefertiti bestowing gold-collars upon favourite courtiers.

Between the king and queen is the princess Ankh-s-en-pa-Aten,

who married Tutankhamen, and behind the queen are two of her other daughters.

As the buildings increased in Aakhutaten and the cult of Aten developed, the king's love for his new city grew, and he devoted all his time to the worship of his god. Surrounded by his wife and family and their friends, and his obedient officials, who seem to have been handsomely rewarded for their devotion, the king had neither wish nor thought for the welfare of his kingdom, which he allowed to manage itself. His religion and his domestic happiness filled his life, and the inclinations and wishes of the ladies of his court had more weight with him than the counsels and advice of his ablest officials. We know nothing of the forms and ceremonies of the Aten worship, but hymns and songs and choruses must have filled the temple daily. And the stele of Tutankhamen proves (see p. 9) that a considerable number of dancing men and acrobats were maintained by the king in connection with the service of Aten. Not only was the king no warrior, he was not even a lover of the chase. As he had no son to train in manly sports and to teach the arts of government and war, for his offspring consisted of seven daughters,1 his officers must: have wondered how long the state in which they were then living would last. The life in the City of Aten was no doubt pleasant enough for the Court and the official classes, for the king was generous to the officers of his government in the City, and, like the Pharaohs of old, he gave them when they died tombs in the hills in which to be buried. The names of many of these officers are well known, e.g., Merira I, Merira II, Pa-nehsi (the Negro), Hui, Aahmes, Penthu, Mahu, Api, Rames, Suti, Nefer-kheperu-her-sekheper, Parennefer, Tutu, Ai, Mai, Ani, etc.2

Amenhetep IV and his Queen Nefertiti and some of the daughters seated with the rays of Aten falling upon them.

The queen wears the disk, horns and plumes of Hathor and Isis.

The abnormal development of the lower part of the body seems to be

a characteristic of every member of the royal family.

The tombs of these men are different from all others of the

same class in Egypt. The walls are decorated with pictures

representing

(1) the worship of Aten by the king and his mother;

(2) the bestowal of gifts on officials by the king;

(3) the houses, gardens and estates of the nobles;

(4) domestic life, etc.

The hieroglyphic texts on the walls of the tombs contain the names of those buried in them, the names of the offices which they held under the king, and fulsome adulation of the king, and of his goodness, generosity and knowledge. Then there are prayers for funerary offerings, and also Hymns to Aten. The long Hymn in the tomb of Ai is not by the king, as was commonly supposed; it is the best of all the texts of the kind in these tombs, and many extracts from it are found in the tombs of his fellow officials. A shorter Hymn occurs in some of the tombs, and of this it is probable that Aakhunaten was the author. We look in vain for the figures of the old gods of Egypt, Ra, Horus, Ptah, Osiris, Isis, Anubis, and the cycles of the gods of the dead and of the Tuat (Underworld), and not a single ancient text, whether hymn, prayer, spell, incantation, litany, from the Book of the Dead in any of its Recensions is to be found there. To the Atenites the tomb was a mere hiding place for the dead body, not a model of the Tuat, as their ancestors thought. Their royal leader rejected all the old funerary Liturgies like the "Book of Opening the Mouth," and the "Liturgy of funerary offerings," and he treated with silent contempt such works as the "Book of the Two Ways," the "Book of the Dweller in the Tuat," and the "Book of Gates."

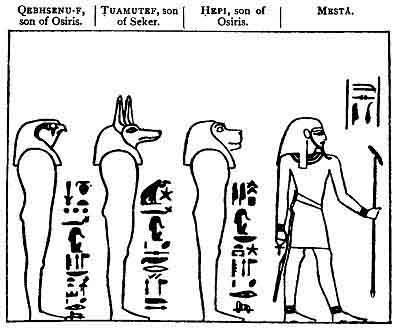

The four grandsons of Horus the Aged.

They were the gods of the four cardinal points, and later, as the sons of Osiris, protected the viscera of the dead.

Thus it would appear that he rejected en bloc all funerary rites and ceremonies, and disapproved of all services of commemoration of the dead, which were so dear to the hearts of all Egyptians. The absence of figures of Osiris in the tombs of his officials and all mention of this god in the inscriptions found in them suggests that he disbelieved in the Last judgment, and in the dogma of rewards for the righteous and punishments for evil doers. If this were so, the Field of Reeds, the Field of the Grasshoppers, the Field of Offerings in the Elysian Fields, and the Block of Slaughter with the headsman Shesmu, the five pits of the Tuat, and the burning of the wicked were all ridiculous fictions to him. Perhaps they were, but they were ineradicably fixed in the minds of his subjects, and he gave them nothing to put in the place of these fictions. The cult of Aten did not satisfy them, as history shows, for right or wrong, the Egyptian, being of African origin, never understood or cared for philosophical abstractions.

Another question arises: did the Atenites mummify their dead? It is clear from the existence of the tombs in the hills about Aakhunaten that important officials were buried; but what became of the bodies of the working class folk and the poor? Were they thrown to the jackals "in the bush"? All this suggests that the Atenites adored and enjoyed the heat and light which their god poured upon them, and that they sang and danced and praised his beneficence, and lived wholly in the present. And they worshipped the triad of life, beauty and colour. They abolished the conventionality and rigidity in Egyptian painting and sculptures and introduced new colours into their designs and crafts, and, freed from the control of the priesthoods, artists and workmen produced extraordinarily beautiful results. The love of art went hand in hand with their religion and was an integral part of it. We may trace its influence in the funerary objects, even of those who believed in Osiris and were buried with the ancient rites and ceremonies especially in figures, vases, etc., made of pottery. Perhaps the brightly coloured vignettes, which are found in the great rolls of the Book of the Dead that were produced at this period, were painted by artists who copied the work of Atenite masters.

Amenhetep IV seated on his portable lion-throne beneath the

rays of Aten;

he holds in his hands the old Pharaonic symbols of

sovereignty ![]() and

dominion

and

dominion ![]()

Now whilst Aakhunaten was organizing and developing the cult of Aten, and he and his Court and followers were passing their days and years in worshipping their god and in beautifying their houses, what was happening to the rest of Egypt? Tutankhamen tells us that the revenues of the gods were diverted to the service of Aten, that the figures of the gods had disappeared from their thrones, that the temples were deserted, and that the Egyptians generally were living in a state of social chaos. For the first twelve years; or so of Aakhunaten's reign the tribute of the Nubians was paid, for the Viceroy of Nubia had at hand means for making the tribes bring gold, wood, slaves, etc., to him. In the north of Egypt General Heremheb, the Commander-in-Chief, managed to maintain his lord's authority, but there is no doubt, as events showed when he became king of Egypt, that he was not a wholly sincere worshipper of Aten, and that his sympathies lay with the priesthoods of Ptah of Memphis and Ra of Heliopolis. The Memphites and the Heliopolitans must have resented bitterly the building of temples to Aten in their cities, and there can be little doubt that that astute soldier soon came to an understanding with them. Moreover, he knew better than his king what was happening in Syria, and how the Khabiru were threatening Phœnicia from the south, and how the Hittites were consolidating their position in Northern Syria, and increasing their power in all directions. He, and every one in Egypt who was watching the course of events, must have been convinced that no power which the king could employ could stop the spread of the revolt in Western Asia, and that the rule of the Egyptians there was practically at an end.

When the king as Amenhetep IV ascended the throne, all his father's friends in Babylonia, Assyria, Mitanni, the lands of the Kheta and Cyprus hastened to congratulate him, and all were anxious to gain and keep the friendship of the new king of Egypt. Burraburiyash, king of Karduniash, hoped that the new king and he would always exchange presents, and that the old friendship between his country and Egypt would be maintained. Ashuruballit sent him gifts and asked for 20 talents of gold in return. Tushratta, king of Mitanni, addressed him as "my son-in-law," sent greetings to Queen Ti, and spoke with pride of the old friendship between Mitanni and Egypt.

The rays of Aten giving "life" to Amenhetep IV whilst he is bestowing gifts on his favourite courtiers.

He also wrote to Queen Ti, and again refers to the old friendship. But Aakhunaten did not respond in the manner they expected, and letters sent by them to him later show that the gifts which he sent were mean and poor. Clearly he lacked the open-handedness and generosity of his father Amenhetep III. As years went on, the governors of the towns and cities that were tributaries of Egypt wrote to the king protesting their devotion, fidelity and loyalty, many of them referring to favours received and asking for new ones. Very soon these protestations of loyalty were coupled with requests for Egyptian soldiers to be sent to protect the king's possessions. Thus one Shuwardata writes: To the king, my lord, my gods and my Sun. Thus saith Shuwardata, the slave: Seven times and seven times did I fall down at the feet of the king my lord, both upon my belly and upon my back. Let the king, my lord, know that I am alone, and let the king, my lord, send troops in great multitudes, let the king, my lord, know this.1

The people of Tunip, who were vassals of Thothmes III, wrote and told the king that Aziru had plundered an Egyptian caravan, and that if help were not sent Tunip would fall as Ni had already done. Rib-Adda of Byblos writes: We have no food to eat and my fields yield no harvest because I cannot sow com. All my villages are in the hands of the Khabiru. I am shut up like a bird in a cage, and there is none to deliver me. I have written to the king, but no one heeds. Why wilt thou not attend to the affairs of thy country? That "dog," Abd-Ashratum, and the Khabiri have taken Shigata and Ambi and Simyra. Send soldiers and an able officer. I beseech the king not to neglect this matter. Why is there no answer to my letters? Send chariots and I will try to hold out, else in two months' time Abd-Ashratum will be master of the whole country. Gebal (Byblos) will fall, and all the country as far as Egypt will be in the hands of the Khabiri. We have no grain; send grain. I have sent my possessions to Tyre, and also my sister's daughters for safety. I have sent my own son to thee, hearken to him. Do as thou wilt with me, but do not forsake thy city Gebal. In former times when Egypt neglected our city we paid no tribute; do not thou neglect it. I have sold my sons and daughters for food and have nothing left. Thou sayest, "Defend thyself," but how can I do it? When I sent my son to thee he was kept three months waiting for an audience. Though my kinsmen urge me to join the rebels, I will not do it.

Abi-Milki of Tyre writes: To the king, my lord, my gods, my Sun. Thus saith Abi-Milki, thy slave. Seven times and seven times do I fall down at the feet of the king my lord. I am the dust under the sandals of the king my lord. My lord is the sun that riseth over the earth day by day, according to the bidding of the Sun, his gracious Father. It is he in whose moist breath I live, and at whose setting I make my moan. He maketh all the lands to dwell in peace by the might of his hand; he thundereth in the heavens like the Storm-god, so that the whole earth trembleth at his thunder. . . . Behold, now, I said to the Sun, the Father of the king my Lord, When shall I see the face of the king my Lord? And now behold also I am guarding Tyre, the great city, for the king my lord until the king's mighty hand shall come forth unto me to give me water to drink and wood to warm myself withal. Moreover, Zimrida, the king of Sidon, sendeth word day by day unto the traitor Aziru, the son of Abd-Ashratum, concerning all that he hath heard from Egypt. Now behold, I have written unto my lord, for it is well that he should know this.

In a letter from Lapaya the writer says: If the king were to write to me for my wife I would not refuse to send her, and if he were to order me to stab myself with a bronzed dagger I would certainly do so. Among the writers of the Letters is a lady who reports the raiding of Ajalon and Sarha by the Khabiri. All the letters tell the same story of successful revolt on the part of the subjects of Egypt and the capture and plundering and burning of towns and villages by the Khabiri, and the robbery of caravans on all the trade routes. And whilst all this was going on the king of Egypt remained unmoved and only occupied himself with the cult of his god! The general testimony of the Tall al-'Amarnah Letters proves that he took no trouble to maintain the friendly relations that had existed between the kings of Babylonia and Mitanni and his father. He seems to have been glad enough to receive embassies and gifts from Mesopotamia, and to welcome flattering letters full of expressions of loyalty and devotion to himself, but the gifts which he sent back did not satisfy his correspondents. He sent little or no gold to be used in decorating temples in Mesopotamia and for making figures of gods, and some of the letters seem to afford instances of double-dealing on the part of the king of Egypt. At all events, he waged no wars in Mesopotamia, and when one city after another failed to send tribute he made no attempt to force them to do so. It is uncertain how much he really knew of what was happening in Western Asia, but when Tushratta and others sent him dispatches demanding compensation for attacks made upon their caravans, when passing through his territory, he must have realized that the power of Egypt in that country had greatly weakened.

As the years went on he must have known that the Egyptians hated his god and loathed his rule, and such knowledge must have, more or less, affected the health of a man of his physique and character.

During the earlier years of his reign painters and sculptors gave him the conventional form of an Egyptian king, but later he is represented in an entirely different manner. He had naturally a long nose and chin and thick, protruding lips, and he was somewhat round-shouldered, and had a long slim body, and he must have had some deformity of knees and thighs. On the bas-reliefs and in the paintings all these physical characteristics are exaggerated, and the figures of the king are undignified caricatures.1 But these must have been made with the king's knowledge and approval, and must be faithful representations of him as he appeared to those who made them. In other words, they are examples of the realism in art (which he so strongly inculcated in the sculptors and artists who claimed to be his pupils) applied to himself. History is silent as to the last years of his reign, but the facts now known suggest that, overwhelmed by troubles at home and abroad, and knowing that he had no son to succeed him, and that he had failed to make the cult of Aten the national religion, his proud and ardent spirit collapsed, and with it his health, and that he became a man of sorrow. Feeling his end to be near, he appointed as co-regent Sakara tcheser-kheperu, who had married his eldest daughter Merit-Aten, and died probably soon afterwards. He was buried in a rock-hewn tomb, which he had prepared in the hills five miles away on the eastern bank of the Nile instead of in the western hills, where all the kings of the XVIIIth dynasty were buried. Even in the matter of the position of his tomb he would not follow the custom of the country. This tomb was found in 1887-8 by native diggers, who cut out the cartouches of the king and sold them to travellers.

Under the section dealing with Amenhetep III reference has beep. made to the series of large steatite scarabs on which this king commemorated in writing noteworthy events in his life. Up to the present nothing has been found at Tall al-'Amarnah or in Egypt which would lead us to suppose that his son Amenhetep IV copied his example, but a very interesting scarab found at Sadenga in the Egyptian Sudan1 proves that he did, at least on one occasion. This scarab is now in the British Museum (No. 51084). On one side of the body of the scarab is the king's prenomen and on the other is his nomen. the base, which is mutilated at the sides, are seven lines of text.

This inscription shows that the scarab was made for Amenhetep IV before he adopted his new name of Aakhunaten. The last three lines give names and titles of the king and his queen, and the first four contain an address or prayer concerning some god. The breaks at the beginnings and ends of the lines do not permit a connected translation to be made, but the general meaning of the inscription is as follows:--

"The king of the South and of the North, Nefer-kheperu-Ra-ua-en-Ra, giver of life, son of Ra, loving him, Amenhetep, God, Governor of Thebes, great in the duration of his life, [and] the great royal wife Nefertiti, living and young, say: Long live the Beautiful God, the great one of roarings (thunders?) in the great and holy name of . . . Dweller in the Set Festival like Ta-Thunen, the lord of . . . the Aten (Disk) in heaven, stablished of face, gracious (or pleasant) in Anu (On)." This address or prayer seems to have been made to some Thunder-god, whose name was great and holy: the ordinary god of the thunder in Egypt was Aapep, who in this character is called "Hemhem-ti." The mention of Tathunen is interesting, for he was, of course, one of the "gods" whom Amenhetep IV at a later period of his life wished to abolish. Can this inscription represent an attempt to assimilate an indigenous Sudani Thunder-god with Aten? The writer of one of the Tall al-'Amarnah Letters quoted above (p. 101) speaks of the Thundering of Amenhetep IV, and says that when he thunders all the people quake with fear. From this it seems that some phase of Aten was associated in the minds of foreigners with the Thunder-god, but there is no evidence to show who that god was.

The facts known about the life and reign of Aakhunaten seem to me to prove that from first to last he was a religious fanatic, intolerant, arrogant and obstinate, but earnest and sincere in his seeking after God and in his attempts to make Aten the national god of Egypt. Modern writers describe him as a "reformer," but he reformed nothing. He tried to force the worship of "Horus of the Two Horizons in his name of Shu (i.e., Heat) who is in the Aten" upon his people and failed. When he found that his subjects refused to accept his personal views about an old, perhaps the oldest, solar god, whose cult had been dead for centuries, he abandoned the capital of his great and warlike ancestors in disgust, and like a spoilt child, which no doubt he was, he withdrew to a new city of his own making. Like all such religious megalomaniacs, so long as he could satisfy his own peculiar aspirations and gratify his wishes, no matter at what cost, he was content. Usually the harm which such men do is limited in character and extent, but he, being a king, was able to inflict untold misery on his country during the seventeen years of his reign. He spent the revenues of his country on the cult of his god, and in satisfying his craving for beauty in shape and form, and for ecstatic religious emotion; Though lavish in the rewards in good gold and silver to all those who ministered to this craving, he was mean and niggardly when it came to spending money for the benefit of his country. The Tall al-'Amarnah Letters make this fact quite clear. The peoples of Western Asia might think and say that the King of Egypt had "turned Fakir," but there was little asceticism in his life. His boast of "living in reality," or "living in truth," which suggests that he lived a perfectly natural and simple life, seeing things as they really were, on the face of it seems to be ludicrous. Aakhunaten had much in common with Hakim, the Fatimid Khalifah of Egypt (A.D. 996-1021). Each was the son of a wealthy, pleasure-loving, luxurious father, and each succeeded to the throne when he was a boy. Each had a strange face, each was moved to break with tradition and introduce new ideas, but the spirit in which each made changes was that of a mad reformer. Christians and Jews were to Al-Hakim what the Amenites were to Aakhunaten. Both king and Khalifah were pious in an intolerant and arrogant fashion, and each was a builder of places for worship. Each thought that he was the incarnation of God, and each usurped the attributes of the Deity, and prescribed rules for worship. Each was a patron of the arts, but there is no evidence that the Pharaoh encouraged learned men to flock to his Court as did the Khalifah. Al-Hakim frequently had his enemies murdered, and in his fits of rage had people killed wholesale. Though we have no knowledge that such atrocities were committed at Aakhutaten, yet it would be rash to assume that persons who incurred the king's displeasure in a serious degree were not removed by the methods that have been well known at Oriental Courts from time immemorial.

Aakhunaten was succeeded by his co-regent Sakara, whose reign was probably very short and unimportant. He was the son-in-law of the king and a devoted worshipper of Aten, whose cult he wished to make permanent. Nothing is known of his acts or whether deposition or death removed him from the throne. He was succeeded by Tutankhamen, whose reign has been already described. The short reign of Ai, who had married the nurse of Amenhetep IV, and was Master of the Horse, followed, and he was succeeded by Her-em-heb, a military officer who served in the north of Egypt during the reign of Aakhunaten. The restoration of the cult of Amen begun by Tutankhamen was finally confirmed by him, and the triumph of Amen was complete. The immediate result of this was the decline and fall of the cult of Aten, and the city "Horizon of Aten" lost all its importance and fell into decay. The artisan classes, finding no work, migrated to Thebes and other places where they could ply their crafts in the service of Amen, and many of the Atenites abandoned their god and transferred their worship to Amen. It is probable that the temples and houses of the officials were plundered by the mob, who treated them in the way that the property of an overthrown religious faction has always been treated in the East. The forsaken city soon fell into ruins and was never rebuilt or again inhabited. A liberal estimate for the life of the city is 50 years.

The remains of Aakhutaten are marked to-day by the ruins and rock-hewn tombs which lie near the Arab villages of Hagg Kandil and At-Tall, and are commonly known as "Tall al-'Amarnah." In 1887 this name was in common use among the Egyptians of Upper Egypt, and I asked Mustafa Agha, H.B.M.'s Vice-Consul at Luxor, to explain it. He said that the Bani 'Amran Arabs settled at At-Tall (ordinarily pronounced At-Tell, or even At-Till), and that for many years the Village was known as "Tall Bani 'Amran." When most of the Bani 'Amran left the place and returned to the desert, the village was called "Tall al-'Amarnah" (pronounced Tellel-'Amarnah). The site, which is a very large one, needs careful excavation from one end to the other, for only here can possibly be found material for the real history of Amenhetep IV and his reign. The discoveries already made there prove this, for over three hundred Letters and Despatches written in cuneiform from kings and governors in Western Asia were found on the site by a woman in 1887,1 and she sold them to a neighbour for 10 piastres (2s.). As a result of the woman's discovery Petrie made excavations at Tall al-'Amarnah and succeeded in finding several small fragments and chips of lists of signs and words, etc., and some beautifully painted pavements.2 The Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft began to excavate there in 1913, and in the year following they discovered a number of very important objects, among which may be specially mentioned a cuneiform tablet and a marvellously beautiful head of Queen Nefertiti, which is now in the Museum at Berlin. This head is the finest example known of the painted sculpture work from Tall al-'Amarnah, and should have been kept in Egypt and placed in the Egyptian Museum at Cairo. This oversight on the part of the officials of the Cairo Museum seems to require an explanation. Among the cuneiform fragments discovered by the German excavators at Tall al-'Amarnah in 1913 was one which was inscribed with a legend describing the expedition of Sargon of Akkad to Asia Minor. The original text of the legend of the "King of the Battle" is published by Schroeder in Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmäler, xii, pp. 2-4, and it has been translated by Weidner under the title of Der Zug Sargons von Akkad nach Kleinasien.

In the winter of 1920-21 the Egypt Exploration Society sent out an expedition to Tall al-'Amarnah, under the direction of Prof. T. E. Peet, to carry on the work of excavation from the point where the Germans left it in 1914. During the course of the work a considerable number of very interesting objects were found, including a fragment of a cuneiform tablet, inscribed with a list of signs, and some fine examples of variegated glass vessels and pottery. The data he collected1 answered a number of questions and settled some difficulties, and the Society determined to continue their excavation of the site. In 1922 Mr. Woolley succeeded Prof. Peet as Director of the Expedition, and continued the work as long as funds permitted. The discovery made by Lord Carnarvon and Mr. Howard Carter in December, 1922, has stirred up public interest in all that concerns the reigns of Tutankhamen and his predecessor Amenhetep IV, the notorious "Heretic King." It is more necessary now than ever that excavations should be carried on until the ruins at Tall al-'Amarnah have been thoroughly cleared and examined. In order to do this the Egypt Exploration Society must be liberally supported, and everyone who is interested in the History and Religion of the ancient Egyptians should subscribe to this work. Like everything else, the cost of excavating sites has increased in recent years, and subscriptions to the Society have not increased in proportion to the expenses. The President of the Society is the Right Hon. General J. Grenfell Maxwell, G.C.B., who is himself an ardent collector of Egyptian antiquities, and the Hon. Secretary is Dr. H. R. Hall, Deputy Keeper of the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities in the British Museum. The excavations and other operations of the Society are conducted with strict regard to efficient economy, and all the objects obtained from the excavations are distributed gratis among Museums.

HYMNS TO ATEN.

The first Hymn (A) is put into the mouth of Aakhunaten, and is known as the "Shorter Hymn to Aten." Several copies of it have been found in the tombs at Tall al-'Amarnah. Texts of it have been published by Bouriant, Daressy, Piehl and others, but the most correct version is that copied from the tomb of Api and published by Mr. N. de G. Davies.1 The second Hymn (B) is found in the tomb of Ai, and is known as the "Longer Hymn to Aten." The text was first published by Bouriant in Mission Archéologique, tom. I, p. 2, but badly, and he revised it in his Monuments du Culte d'Atonou, I., pl. xvi. A good text with a Latin translation was published by Breasted in his De Hymnis in Solem sub rege Amenophide IV conceptis, Berlin, 1894, and English versions of most of it were given by him in his History of Egypt, p. 315, and in other publications. Other versions and extracts have been published by Griffith, World's Literature, p. 5225; Wiedemann, Religion, pp. 40-42; Hall, Ancient History, p. 306; Erman, Religion, p. 64, etc.

The best text yet published is that of Davies1 and that, with a few trivial alterations, is reproduced in the following pages. In recent years this Hymn has been extolled as a marvellously beautiful religious composition, and parts of it have been compared with some of the Hebrew Psalms. In consequence it has been regarded as an expression of sublime human aspirations, and the outcome of a firm belief in a God who was a counterpart of the Yahweh of the Hebrews and identical with God Almighty. But if we examine the Hymn., line by line, and compare it with the Hymns to Ra, Amen and other gods, we find that there is hardly an idea in it which is not borrowed from the older Egyptian religious books. Aten is called the eternal, almighty, self-produced, living, or self-subsisting, creator of heaven and earth and all that is in them, and "one god alone." His heat and light are the sources of all life and only for these and the material benefits that they confer on man and beast is Aten praised in these hymns. There is nothing spiritual in them, nothing to appeal to man's higher nature.

The language in which they are written is simple and clear, but there is nothing remarkable about the phraseology, unless the statements are dogmatic declarations like the articles of a creed. A very interesting characteristic of the hymns to Aten is the writer's insistence on the beauty and power of light, and it may be permitted to wonder if this is not due to Mitannian influence, and the penetration into Egypt of Aryan ideas concerning Mitra, Varuna, and Surya or Savitri, the Sun-god. Aten, or Horus of the Two Horizons, corresponds closely to Surya, the rising and setting sun, Ra to Savitri, the sun shining in full strength, "the golden-eyed, the golden-handed, and golden tongued." "As the Vivifier and Quickener, he raises his long arms of gold in the morning, rouses all beings from their slumber, infuses energy into them, and buries them in sleep in the evening."1 Surya, the rising and setting sun, like Aten, was the great source of light and heat, and therefore Lord of life itself. He is the Dyaus Pitar, the "Heaven-Father." Aten, like Surya, was the "fountain of living Light,"2, with the all-seeing, eye, whose beams revealed his presence, and "gleaming like brilliant flames "3 went to nation after nation. Aten was not only the light of the sun which seems to give new life to man and to ail creation, but the giver of light and all life in general. The bringer of light and life to-day, he is the same who brought light and life on the first of days, therefore Aten is eternal. Light begins the day, so it was the beginning of creation; therefore Aten is the creator, neither made with hands nor begotten, and is the Governor of the world. The earth was fertilized by Aten, therefore he is the Father-Mother of all creatures.

His eye saw everything and knew everything. The hymns to Aten suggest that Amenhetep IV and his followers conceived an image of him in their minds and worshipped him inwardly. But the abstract conception of thinking was wholly inconceivable to the average Egyptian, who only understood things in a concrete form. It was probably some conception of this kind that made the cult of Aten so unpopular with the Egyptians, and caused its downfall. Aten, like Varuna, possessed a mysterious presence, a mysterious power, and a mysterious knowledge. He made the sun to shine, the winds were his breath, he made the sea, and caused the rivers to flow. He was omniscient, and though he lived remote in the heavens he was everywhere present on earth. And a passage in the Rig-Veda would form an admirable description of him.

Light-giving Varuna! Thy piercing glance doth scan

In quick succession all this stirring active world.

And penetrateth, too, the broad ethereal space,

Measuring our days and nights and spying out all creatures.1

But Varuna possessed one attribute, which, so far as we know, was wanting in Aten; he spied out sin and judged the sinner. The early Aryan prayed to him, saying, "Be gracious, O Mighty God, be gracious. I have sinned through want of power; be gracious. What great sin is it, Varuna, for which thou seekest in thy worshipper and friend? Tell me, O unassailable and self-dependent god; and, freed from sin, I shall speedily come to thee for adoration."2

And Varuna was a constant witness of men's truth and falsehood. The early Aryan also prayed to Surya, and addressed to him the Gayatri, a formula which is the mother of the Vedas and of the Brahmans. He said to the god, "May we attain the excellent glory of the divine Vivifier: so may he enlighten or stimulate our understanding." The words secured salvation for a man.1 No consciousness of sin is expressed in any Aten text now known, and the Hymns to Aten contain no petition for spiritual enlightenment, understanding or wisdom. For what then did the follower of Aten pray? An answer to this question is given in the Teaching of Amenemapt, the son of Kanekht, who says:--

"Make the prayer which is due from thee to the Aten, when he

is rising,

Say, Grant to me, I beseech, strength [and] health.

He will give thy provision for the life.

And thou shalt be safe from that which would terrify

[thee]."2

Footnotes

75:1 See Davis, The Tomb of Queen Tiyi, London, 1910.

77:1 Ancient History of the Near East, p. 298.

80:1 The object of this festival seems to have been to prolong the life of the king, who dressed himself as Osiris, and assumed the attributes of Osiris, and by means of the rites and ceremonies performed became absorbed into the god. In this way the king renewed his life and divinity.

91:1 Babylonian Room, Table-Case F. No. 72 (29855).

92:1 The names of the seven daughters of Aakhunaten were 1. Aten-merit, 2. Maket-Aten, 3. Ankh-s-en-pa-Aten, 4. Nefer-neferu-Aten the little, 5. Nefer-neferu-Ra, 6. Setep-en-Ra, 7. Bakt-Aten. The first daughter married her father's co-regent, Sakara. The second died young and was buried in a tomb in the eastern hills. The third married Tutankhaten (Amen).

92:2 The tombs of all these have been admirably published by Davies, The Rock Tombs of El-Amarna. Six vols. London, 1903-08.

100:1 All these letters and reports are written in cuneiform upon clay tablets, of which over three hundred were found by a native woman at Tall al-'Amarnah in 1887-8. Summaries of the contents of those in the British Museum were published by Bezold and Budge in Tell el-Amarna Tablets, London, 1892, and by Bezold in Oriental Diplomacy, London, 1893. The texts of all the letters in London, Berlin, and Cairo were published, together with a German translation of them, by Winckler; another German translation was published by Knudtzon. The texts, with translations by Thureau-Dangin, of the six letters acquired by the Louvre in 1918, are published in Revue d'Assyriologie, Vol. XIX, Paris, 1921. Three of the letters are from Palestinian governors and two from Syrian chiefs; the third is by the King of Egypt and is addressed to Intaruda, governor of Aksaph.

103:1 Some interesting remarks by Dr. H. Asselbergs on the old and new style of bas-relief work in the reign of Amenhetep IV, with a photographic reproduction of a block published by Prisse in his Monuments, plate 10, No. 1, will be found in Aegyptische Zeitschrift, Band 58 (1923), P. 36 ff.

104:1 It was first Published by Hall, Catalogue of Scarabs, p. 302.

109:1 This discovery has been attributed to Petrie by Mr. Garvin in the Observer, February 25, 1923. I have told the true story of the "find" in my Nile and Tigris, Vol. I, p. 140 ff.

109:2 He dug there from November, 1891, to the end of March, 1892. See his Tell el Amarna, London, 1894, 4to.

110:1 See his preliminary Report in the Journal of Egyptian Archæology, Vol. VII (1921), p. 169 ff.

111:1 For the published literature see his Rock Tombs, Vol. IV, p. 28.

112:1 Ibid., Vol. VI, pl. xxvii.

113:1 Wilkins, Hindu Mythology, p. 33.

113:2 See Martin, Gods of India, p. 35.

113:3 Monier-Williams, Indian Wisdom, p. 19.

114:1 Monier-Williams' translation.

114:2 Rig-Veda, VII, 86, 3-6.

115:1 Martin, The Gods of India, p. 39.

115:2 Hieratic Papyri in the British Museum, ed. Budge, 2nd Series, London, 1923, pl. 5.