Tutankhamen

Amenism, Atenism And Egyptian Monotheism

By E.A.W. Budge. 1923

Index | Previous | Next

THE CULT OF ATEN,

THE GOD AND DISK OF THE SUN, ITS ORIGIN,

DEVELOPMENT AND DECLINE.

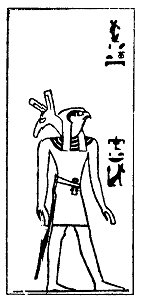

Amongst all the mass of the religious literature of Ancient Egypt, there is no document that may be considered to contain a reasoned and connected account of the ideas and beliefs which the Egyptians associated with the god Aten. The causes of his rise into favour towards the close of the XVIIIth dynasty can be surmised, and the principal dogmas which the founder of his cult and his followers promulgated are discoverable in the Hymns that are found on the walls of the rock-hewn tombs of Tall al-'Amarnah; but the true history of the rise, development and fall of the cult can never be completely known. The word aten or athen is a very old word for the "disk" or "face of the sun," and Atenism was beyond doubt an old form of worship of the sun. But there were many forms of sun-worship older than the cult of Aten, and several solar gods were worshipped in Egypt many. many centuries before Aten was regarded as a special form of the great solar god at all. One of the oldest forms of the Sun-god worshipped in Egypt was HER (Horus), who in the earliest times seems to have represented the "height" or "face" of heaven by day. He was symbolized by the sparrowhawk, the right eye of the bird representing the sun and his left the moon.

In later times he was called "Her-ur" or "Her-sems," the "older Horus," and it was he who fought daily against Set, the darkness of night and the night Sky, and triumphed over him.

The oldest seat of the cult of the Sun-god was the famous city of Anu the On of the Bible, and the Heliopolis of Greek and Latin writers.

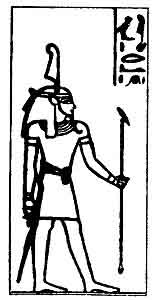

Here, from time immemorial, existed a temple dedicated to the Sun-god, and attached to it was a college of his priests, who from a very remote period were renowned for their wisdom and learning. They called their god TEM or ATEM and in later times, at least, he was depicted in the form of a man wearing the Crowns of the South and North, and holding in his right hand ankh ("life") and in his left a sceptre. He was king of heaven and also of Egypt. He was a solar god and, like every other ancient god in Egypt, had absorbed the attributes of several indigenous gods whose names even are now not known.

|

|

The Pyramid Texts show that he was all-powerful in heaven, and that his priests proclaimed him to be the greatest of all the gods. The supremacy of Tem is asserted in the various versions of the Book of the Dead, and all the other solar gods are regarded as forms of him in the various recensions of this work. Thus in the XVIIth Chapter he says: "I am Tem in his rising. I was the Only One [when] I came into existence in Nenu (or Nu). I am Ra when he rose for the first time. I am the Great God who created himself [from] Nenu, and who made his names to become the gods of his company. I am he who is irresistible among the gods. I am Tem, the dweller in his Disk, or Ra in his rising in the eastern horizon of the sky. I am Yesterday; I know To-day 'I am the Bennu (i.e., Phoenix) which is in Anu (Heliopolis), and I keep the register of the things which are created and of those which are not yet in existence." The Company of the gods over whom "Father Tem" presided consisted of Shu and Tefnut, Geb and Nut, Osiris and Isis, and Set and Nephthys. According to one tradition, Tem produced Shu and Tefnut from his own body, and these three gods formed the first Triad, or Trinity, Tem saying, "From [being] god one I became three."

In the extract from the XVIIth Chapter given above, we must note that 1. Tem originally existed in Nenu, or Nu, the great mass of primeval waters. 2. He was the Only One in existence when he had come into being. 3. He created himself the Great God. 4. He possessed various names, and these he turned into the gods who formed his Pest or Ennead, merely by uttering their names. 5. He was irresistible among the gods, i.e., he was the Over-lord of the gods. 6. He comprehended time past and time to come. 7. He dwelt in the Solar Disk (Aten). 8. He rose in the sky for the first time under the form of Ra, and he was himself the Bennu, i.e., the Soul of Ra. 9. He kept the Registers of things created and uncreated. Though the papyrus from which we get these facts is not older than the XVIIIth dynasty, each of the statements which are here grouped exists in the various religious texts that were written under the Ancient Empire, say, two thousand years earlier.

Of the style and nature of the worship of Tem we know nothing, but, from the fact that he was depicted in the form of a man, we appear to be justified in assuming that it was of a character

superior to that of the cults of sacred animals, birds and reptiles, which were general in Egypt under the earlier dynasties. Tem, the man-god, absorbed the attributes of Her-ur, the old Sky-god, and of Khepera, the Beetle-god, who represented one or more of the forms of an ancient Sun-god between sunset and sunrise, and of Her-aakhuti ("Horus of the two horizons"). Khepera was the sun during the hour that precedes the dawn. Her was the sun by day, and Tem was the setting sun; the names of these gods are of native origin. We may conclude that the priests of Tem incorporated into their forms of worship as many as possible of the rites and ceremonies to which the people had been accustomed in their worship of the older gods. For there was nothing strange in the absorption of one god by another to the Egyptian, the god absorbed being regarded by him merely as a phase or character of the absorbing god. The Egyptians, like many other Orientals, were exceedingly tolerant in such matters.

The monuments prove that, quite early in the Dynastic Period, there was known and worshipped in Lower Egypt another form of the Sun-god who was called RA. Of his origin and early history nothing is known, and the meaning of his name has not yet been satisfactorily explained. It does not seem to be Egyptian, but it may be that of some Asiatic sun-god, whose cult was introduced into Egypt at a very remote period. His character and attributes closely resemble those of the Babylonian god Marduk, and both Ra and Marduk may be only different names of one and the same ancestor. The centre of the cult of Ra in Egypt was Anu, or Heliopolis, and the city must have been inhabited by a cosmopolitan population (who were chiefly worshippers of the sun) from time immemorial. All the caravans from Arabia and Syria halted there, whether outward or homeward bound, and men of many nations and tongues must have exchanged ideas there as well as commodities. The control of the water drawn from the famous Well of the Sun, the 'Ain ash-Shams' of Arab writers, was, no doubt, in the hands of the priests of Anu, and the payments made by grateful travellers for the watering of their beasts, together with other offerings, made them rich and powerful. The waters of the well were believed to spring from the celestial waters of Nenu, or Nu, and the Nubian King Piankhi tells us that when he went to Anu he bathed his face in the water in which Ra was wont to bathe his face.1 We may note in passing that the Virgin Mary drew water from this well when the Holy Family halted at Anu.

Under the IVth dynasty the priests of Anu obtained very

considerable power, and they succeeded in acquiring pre-eminence

for their god Ra among the other gods of Lower Egypt. Whether or

not they chose the kings cannot be said, but it is certain that

they caused the name of Ra to form a part of the Nesu bat names

of the builders of the second and third pyramids at Gizah. Thus

we have KHAF-RA (Khephren) and MENKAU-RA (Mycerinus). Not

satisfied with this, they rejected the descendants of the great

pyramid builders, and set upon the throne a number of kings whom

they declared to be the sons of their god Ra by the wife of one

of his priests. The first of these adopted as his fifth, or

personal name, the title of "Sa Ra," i.e., son of Ra. This

title, which was certainly adopted by the kings of the Vth

dynasty, was borne by every king of Egypt afterwards, and the

Nubian, Persian, Macedonian, or Roman who became king of Egypt

saw no absurdity in styling himself "son of Ra." Thanks to the

excavations made by Borchardt and Schäfer, under the

direction of F. von Bissing, several important facts dealing with

the worship of Ra have been brought to light. The sun temples

built by the later kings of the Vth dynasty were usually

buildings about 325 feet long

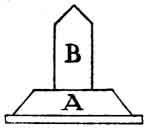

and 245 feet broad. At the west end stood a truncated, or

"blunted," pyramid (A), and on the top of it was an obelisk made

of stone (B).  In front of the east side of the pyramid stood

an alabaster B altar, and on the north side of the altar were

channels along which the blood of the victims, both A animal and

human, ran into alabaster bowls which were placed to receive it.

On the north side of the rectangular walled enclosure was a row

of store rooms, and on the east and south sides were passages,

the walls of which were decorated with reliefs. Opposite the

altar, on the east side, was a gateway; from this ran a path,

which led by an inclined causeway to another gate, Which formed

the entrance to another large enclosure, about 1,000 feet square.

The priests lived in this enclosure, and in special chambers were

kept the sacred objects which were carried in procession on days

of festival.

In front of the east side of the pyramid stood

an alabaster B altar, and on the north side of the altar were

channels along which the blood of the victims, both A animal and

human, ran into alabaster bowls which were placed to receive it.

On the north side of the rectangular walled enclosure was a row

of store rooms, and on the east and south sides were passages,

the walls of which were decorated with reliefs. Opposite the

altar, on the east side, was a gateway; from this ran a path,

which led by an inclined causeway to another gate, Which formed

the entrance to another large enclosure, about 1,000 feet square.

The priests lived in this enclosure, and in special chambers were

kept the sacred objects which were carried in procession on days

of festival.

The principal object of the cult of Ra and his special symbol was the obelisk, but it has been suggested that the earliest worshippers of the sun believed that their god dwelt in a particular stone of pyramidal shape. At stated seasons, or for special purposes, the Spirit of the Sun was induced by the priests to inhabit the stone, and it was believed to be present when gifts were offered up to the god, and when human victims, who were generally prisoners of war, were sacrificed. The exact signification of this sun symbol is not known. Some think that the obelisk represented the axis of earth and heaven, but the Egyptians can hardly have evolved such an idea; others assign to it a phallic signification, and others associate it with an object that produced fire and heat. That it symbolized Ra is certain, and there was in every sanctuary a shrine in which, behind sealed doors, was a model of an obelisk. The cult of the standing stone, or pillar, was probably older than the cult of Ra, and the old name of Heliopolis is Anu, i.e., the city of the pillar.

The Spirit of the Sun visited the temple of the sun from time to time in the form of a Bennu bird, and alighted "on the Ben-stone,1 in the house of the Bennu in Anu in later times the Bennu-bird, which the Egyptians regarded as the "soul of RA," was known as the Phoinix, or Phœnix.

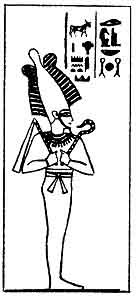

Under the VIth dynasty the priests of Ra succeeded in thrusting their god into the position of over-lord of all the gods, and as we see from the names Ra-Khepera, Ra-Atem, Ra-Heraakhuti and the like, all the old solar gods of the north of Egypt were regarded as forms of Ra. He was king of heaven and judge of gods and men, and the attempt was also made to make the people accept him as the over-lord of Osiris and king of the Tuat, or Underworld. But in this last matter the priests failed, and Osiris maintained his position as the god and judge of the dead. The priests had assigned to Ra in the funerary compositions, which are now known as the "Pyramid Texts," great powers over the dead, and, in fact, over all the gods and demons and denizens of the underworld, but before a century had passed, Osiris had established absolute sovereignty over his realm of Amentt.

From what has been said above it is evident that, before the close of the VIth dynasty, the priests of the various solar gods of Lower Egypt had assigned to each of them all the essential powers and characteristics which Amenhetep claimed for his god Aten. But before we consider these powers in detail we must summarize briefly the principal historical facts relating to the rise and development of the Aten cult. Wherever a solar god was worshipped in Egypt the habitat of this god was believed to be the solar Disk (aten or athen) But the oldest solar god who was associated with the Disk was Tem, or Atmu, who is frequently referred to in religious texts as "Tem in his Disk"; when Ra usurped the attributes of Tem he became the "dweller in his Disk." Heraakhuti was the "god of the two horizons," i.e., the Sun-god by day, from sunrise to sunset, and in the hieroglyphs with which his name is written, we see the Disk resting upon the horizon of the east and the horizon of the west. Thothmes IV, who owed his throne to the priesthoods of Tem and Ra at Heliopolis, incorporated the name of Tem in his Nebti title, and styled himself "made of Ra," "chosen of Ra," and "beloved of Ra." As the name of Amen is wanting in every one of his titles, it seems reasonable to assume that his personal sympathies lay with the cult of the solar gods of the North and not with the cult of Amen of Thebes. But he maintained good relations with the priests of Amen, and made gifts to their god, who through the victories of Thothmes III was recognized in the Egyptian Win, Egypt, and Syria as the god of all the world.

Thothmes IV was succeeded by his son Amenhetep, the third king to bear the name, and the priesthood of Thebes asserted that he was the veritable son of their god Amen, whose blood ran in his veins. According to this fiction the god assumed the form of Thothmes IV, and Queen Mutemuaa became with child by him. How much or how little religious instruction the child received cannot be said, but it is probable that any teaching which he received from his mother, the princess of Mitanni, would make his mind to incline towards the religion of her native land. From the titles which Amenhetep assumed when he became king it is clear that he was content to be "the chosen of Ra," "the chosen of Tem," or "the chosen of Amen," and it seems to have mattered little to him whether he was the "beloved" and "emanation of Ra" or the "beloved" and "emanation of Amen." His predecessors on the throne of Egypt believed in all seriousness that they had divine blood in their veins, and they acted as they thought gods would act; they had themselves hedged round with elaborate ceremonial procedure, which made men believe that their king was a god. To Amenhetep all the gods of Egypt were alike, and we see from the bas-reliefs in the temple at Sulb, some fifty miles above the head of the Second Cataract, that he was as willing to worship himself and to offer sacrifices to himself as to Amen, in whose honour he had rebuilt the temple. It is impossible to think of his performing daily the rites and ceremonies which the king of Egypt was expected to perform in the shrine of Amen-Ra at Karnak, in order to obtain from the god the power and knowledge necessary for governing his people.

One of the most important events in his life, and one fraught with very far-reaching consequences, was his marriage with the lady Ti (or Tei), a private individual, apparently of no high rank or social position.1 In the Tall al-'Amarnah letters her name is transcribed Tei. Her father was called Iuau, and her mother Thuau. Their tomb was discovered in 1905,2 and it is clear that before the marriage of their daughter to Amenhetep III they were humble folk. According to a consensus of modern Egyptological opinion they were natives of Egypt, not foreigners as the older Egyptologists supposed.

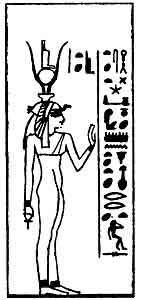

Plate V.

Queen Ti, wife of Amenhetep III. From a drawing in Davis's work on her tomb (Plate XXXIII).

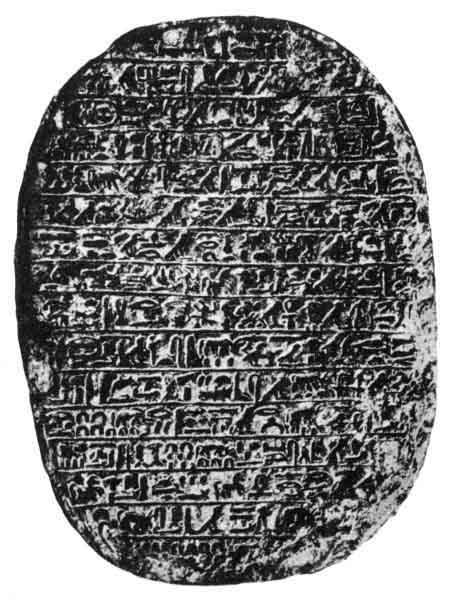

Plate VI.

Large steatite scarab recording the slaughter of two hundred and twenty-six wild cattle by Amenhetep III. British Museum (Fourth Egyptian Room, Table-case B, No. 55585).

Be this as it may, there is no doubt that Ti was a very remarkable woman and that her influence over her husband was very great. Her name appears in the inscriptions side by side with that of her husband, a fact which proves that he acknowledged her authority as co-ruler with himself; and she assisted at public functions and in acts of ceremonial worship in a manner unknown to queens in Egypt before her time. Her power inside the palace and in the country generally was very great, and there is evidence that the king's orders, both private and public, were only issued after she had sanctioned them. In the Sudan the king was worshipped as a god, and as the son and equal and counterpart of Amen-Ra, and in the temple which Amenhetep built for her at Saddenga, some twenty or thirty miles south of Koshah, Ti was worshipped as a goddess. When Amenhetep married her, or perhaps when he became king, he caused a number of unusually large steatite scarabs to be made, with his names and titles and those of Ti cut side by side on their bases.1 On another group of large scarabs he caused his own names and titles, and the names of Ti and her father Iuau and mother Thuau, to be cut, and these are followed by the statement, "[She is] the wife of the victorious king whose territory in the South reaches to Karei (i.e., Napata, at the foot of the Fourth Cataract) and in the North to Naharn" (i.e. the country of the head waters of the Euphrates).2 Perhaps this is another way of saying the great and mighty king Amenhetep was proud to marry the daughter of parents of humble birth and to give her a position equal to his own. And it is possible, as Maspero suggested long ago, that some romantic episode is here referred to, similar to that in the old story where the king marries a shepherdess for love. What Ti's religious views were, or what gods she worshipped, we have no means of knowing, but the inscription which is found repeated on several large steatite scarabs suggests that she favoured the cult of Aten, and that in the later years of her life she was a zealous and devoted follower of that god. To please her Amenhetep caused a great lake to be made on her estate called Tcharukha in Western Thebes. This lake was about 1 1/8 mile (3,700 cubits) long and more than 5/8th of a mile (700 cubits) wide, and its modem representative is probably Birkat Habu. On the sixteenth day of the third month of the season Akhet (October), in the 11th year of his reign, His Majesty sailed over the lake in the barge called ATHEN-TEHEN i.e. "Aten sparkles." And in following years this day was celebrated as a festival. Both lake and barge were made to give the Queen pleasure, and the fact that the name of Aten formed part of the name of the latter, instead of Amen, has been taken to show that both the King and Queen wished to pay honour to this solar god. In fact, it was definitely stated by Maspero that this water procession of the King marked the inauguration of the cult of Aten at Thebes, and he is probably correct.

Amenhetep's children by Ti consisted of four daughters and one son; his daughters were called Ast, Henttaneb, Satamen and Baktenaten, and her son was Amenhetep IV, the famous Aakhunaten. Ti lived in Western Thebes during her husband's lifetime, and she continued to do so after his death. She visited Tall al-'Amarnah from time to time, and was present there in the twelfth year of her son's reign. What appears to be an excellent portrait of her is reproduced on Plate XXXIII of Mr. Davis's book on her tomb.

But his respect for Ti and the honour in which he held her did not prevent Amenhetep from marrying other wives, and we know from the Tall al-'Amarnah tablets that he married a sister and a daughter of Tushratta, the King of Mitanni. His marriage with Gilukhipa, the daughter of Shutarna and sister of Tushratta, took place in the tenth year of his reign. And he commemorated the event by making a group of large scarabs inscribed on their bases with the statement that in the tenth year of his reign Gilukhipa, the daughter of Shutarna, prince of Neherna, arrived in Egypt with her ladies and escort of 317 persons.1 Exactly when Amenhetep married Tushratta's daughter Tatumkhipa is not known, but that he received many gifts with her from her father is certain, for a tablet at Berlin (No. 296) contains a long list of her wedding gifts from her father. In marrying princesses of Mitanni Amenhetep followed the example of his father, Thothmes IV, whose wife, whom the Egyptians called Mutemuaa, was a native of that country. It follows as a matter of course that the influence of these foreign princesses on the King must have been very considerable at the Theban Court, and they and the high officials and ladies who came to Egypt with them would undoubtedly prefer the cult of their native gods to that of Amen of Thebes. Ti's son, Amenhetep IV, and his sisters would soon learn their religious views, and the prince's hatred of Amen and of his arrogant priesthood probably dates from the time when he came in contact with the princesses of Mitanni, and learned to know Mithras, Indra, Varuna and other Aryan gods, whose cults in many respects resembled those of Horus, Ra, Tem and other Egyptian solar gods.

During the early years of his reign Amenhetep spent a great deal of his time in hunting, and to commemorate his exploits in the desert he caused two groups of large scarabs to be made. On the bases of these were cut details of his hunts and the numbers of the beasts he slew. One group of them, the "Hunt Scarabs," tells us that a message came to him saying that a herd of wild cattle had been sighted in Lower Egypt. Without delay he set off in a boat, and having sailed all night arrived in the morning near the place where they were. All the people turned out and made an enclosure with stakes and ropes, and then, in true African fashion, surrounded the herd and with cries and shouts drove the terrified beasts into it. On the occasion which the scarabs commemorate 170 wild cattle were forced into the enclosure, and then the King in his chariot drove in among them and killed 56 of them. A few days later he slew 20 more. This battue took place in the second year of Amenhetep's reign.1

The other group of "Hunt Scarabs" was made in the tenth year of his reign, and after enumerating the names and titles of Amenhetep and his wife Ti, the inscription states that from the first to the tenth year of his reign he shot with his own hand 102 fierce lions.2 No other King of Egypt used the scarab as a vehicle for advertising his personal exploits and private affairs. That Amenhetep had some reason for so doing seems clear, but unless it was to secularize the sacred symbol of Khepera, or to cast good-natured ridicule on some phase of native Egyptian belief which he thought lightly of, this use of the scarab seems inexplicable.

The reign of Amenhetep III stands alone in Egyptian History. When he ascended the throne he found himself absolute lord of Syria, Phoenicia, Egypt and the Egyptian Sudan as far south as Napata. His great ancestor Thothmes III had conquered the world, as known to the Egyptians, for him. Save in the "war" which he waged in Nubia in the fifth year of his reign he never needed to strike a blow to keep what Thothmes III had won. And this "war" was relatively an unimportant affair. It was provoked by the revolt of a few tribes who lived near the foot of the Second Cataract, and according to the evidence of the sandstone stele, which was set up by Amenhetep to commemorate his victory, he only took 740 prisoners and killed 312 rebels.1 In the Sudan he made a royal progress through the country, and the princes and nobles not only acclaimed him as their over-lord but worshipped him as their god. And year by year, under the direction of the Egyptian Viceroy of Kash, they dispatched to him in Thebes untold quantities of gold, precious stones, valuable woods, skins of beasts, and slaves. When he visited Phœnicia, Syria, and the countries round about he was welcomed and acknowledged by the shekhs and their tribes as their king, and they paid their tribute unhesitatingly. The great independent chiefs of Babylonia, Assyria, and Mitanni vied with each other in seeking his friendship, and probably the happiest times of his pleasure-loving life were the periods which he spent among his Mesopotamian friends and allies. His joy in hunting the lion in the desert south of Sinjar and in the thickets by the river Khabur can be easily imagined, and his love for the chase would gain him many friends among the shekhs of Mesopotamia. His visits to Western Asia stimulated trade, for caravans could travel to and from Egypt without let or hindrance, and in those days merchants and traders from the islands and coasts of the Mediterranean flocked to Egypt, where gold was as dust for abundance.

Amenhetep devoted a large portion of the wealth which he had inherited, and the revenues which he received annually from tributary peoples, to enlarging and beautifying the temples of Thebes. He had large ideas, and loved great and splendid effects, and he spared neither labour nor expense in creating them. He employed the greatest architects and engineers and the best workmen, and he gave them a "free hand," much as Hatshepsut did to her architect Senmut. On the east bank he made great additions to the temple of Karnak, and built an avenue from the river to the temple, and set up obelisks and statues of himself. He completed the temple of Mut and made a sacred lake on which religious processions in boats might take place. He joined the temples of Karnak and Luxor by an avenue of kriosphinxes, each holding a figure of himself between the paws, and at Luxor he built the famous colonnade, which is to this day one of the finest objects of its kind in Egypt. On the west bank he built a magnificent funerary temple, and before its pylon he set up a pair of obelisks and the two colossal statues of himself which are now known as the "Colossi of Memnon." A road led from the river to the temple, and each side of it was lined with stone figures of jackals. He also built on the Island of Elephantine a temple in honour of Khnemu, the great god of the First Cataract, and, as already said, he rebuilt and added largely to the temple which had been founded by Amenhetep III at Sulb. All these temples were provided with metal-plated doors, parts of which seem to have been decorated with rich inlays, and colour was used freely in the scheme of decoration. The means at the king's disposal enabled him to employ unlimited labour, and most of his subjects must have gained their livelihood by working for Amen and the king. Under such patrons as these the Arts and Crafts flourished, and artificers in stone, wood, brass, and faïence produced works the like of which had never before been seen in Egypt. Throughout his reign Amenhetep corresponded with his friends in Babylonia, Mitanni, and Syria, and the arrival and departure of the royal envoys gave opportunity for dispensing lavish hospitality, and for the display of wealth and all that it produces. The receptions in his beautifully decorated palace on the west bank of the river must have been splendid functions, such as the Oriental loves. The king spent his wealth royally; and in many ways, probably as a result of the Mitannian blood which flowed in his veins, his character was more that of a rich, luxury-loving, easygoing and benevolently despotic Mesopotamian Shekh than that of a king of Egypt. Very aptly has Hall styled him "Amenhetep the Magnificent." He died after a reign of about thirty-six years, and was buried in his tomb in the Western Valley at Thebes. On the walls of the chambers there are scenes representing the king worshipping the gods of the Underworld, and on the ceiling are some very interesting astronomical paintings.

The tomb was unfinished when the king was buried in it. It was pillaged by the professional robbers of tombs, and the Government of the day removed his mummy to the tomb of Amenhetep II, where it was found by Loret in 1899. Thus whatever views Amenhetep III may have held about Aten, he was buried in Western Thebes, with all the pomp and ceremony befitting an orthodox Pharaoh.

Footnotes

61:1 Stele of Piankhi, l. 102.

63:1 Pyramid Texts, II. N. 663, p. 372.

66:1 See Davis, The Tomb of Queen Tiyi, London, 1910.

66:2 See Davis, Tomb of Iouiya and Touiyou, London, 1907.

67:1 For an example see No. 4094 in the British Museum (Table Case B. Fourth Egyptian Room).

67:2 See Nos. 4096 and 16988.

69:1 See No. 49707 in the British Museum.

70:1 For a fine example of this group of scarabs, see No. 55585 in the British Museum.

70:2 Fine examples in the British Museum are Nos. 4095, 12520, 24169 and 29438.

71:1 The stele was made by Merimes, Viceroy of the Northern Sudan, and set up by him at Samnah, some 30 miles south of Wadi Halfah. It is now in the British Museum. (Northern Egyptian Gallery, No. 411, Bay 6.) An illustration of it will be found in the Guide, p. 115.