Tutankhamen

Amenism, Atenism And Egyptian Monotheism

By E.A.W. Budge. 1923

Index | Previous | Next

THE REIGN OF TUTANKHAMEN.

("Living Image of Amen "), King of Egypt, about B.C. 1400.

WHEN and where TUTANKHAMEN was born is unknown, and there is some doubt about the identity of his father. From a scarab which was found in the temple of Osiris at Abydos,1 we learn that his mother was called Merit-Ra. In the inscription on the red granite lion in the Southern Egyptian Gallery in the British Museum (No. 431), he says that he "restored the monuments of his father, King of the South and North, Lord of the Two Lands, Nebmaatra, the emanation of Ra, the son of Ra, Amenhetep (III), Governor of Thebes." It is possible that Tutankhamen was the son of Amenhetep III by one of his concubines, and that when he calls this king his father the statement is literally true, but there is no proof of it. On the other hand, Tutankhamen may have used the word "father" simply as a synonym of "predecessor." The older Egyptologists accepted the statement made by him on the lion that he dedicated to the Temple of Sulb in Nubia as true, but some of the more recent writers reject it. The truth is that the name of Tutankhamen's father is unknown. He became king of Egypt by virtue of his marriage with princess ANKHSEN-PAATEN, the third daughter of Amenhetep IV1, at least that is what it is natural to suppose, but it is possible that he got rid of his immediate predecessor, Smenkhkara, or Seaakara, who married the princess MERITATEN, or ATENMERIT, the eldest daughter of Amenhetep IV, and usurped his throne.

When Tutankhamen ascended the throne he was, or at all events he professed to be, an adherent of the cult of Aten, or the "Solar Disk," and to hold the religious views of his wife and his father-in-law. Proof of this is provided by the fragment of a calcareous stone stele preserved at Berlin (No. 14197), on which he is described as "Lord of the Two Lands, Rakheperuneb, Lord of the Crowns, Tutankhaten, to whom life is given for ever."2

He did not at once sever his connection with the cult of Aten, for he started work on a temple, or some other building, of Aten at Thebes. This is certain from the fact that several of the blocks of stone which Heremheb, one of his immediate successors, used in his buildings bear Tutankhamen's name. It is impossible to describe the extent of Tutankhamen's building operations, for this same Heremheb claimed much of his work as his own, and cut out wherever possible Tutankhamen's name and inserted his own in its place. He went so far as to usurp the famous stele of Tutankhamen that Legrain discovered at Karnak in 1905.1 From this stele we learn that the "strong names" and official titles which Tutankhamen adopted were as follows:--

1. Horus name. KA-NEKHT-TUT-MES

2. Nebti name. NEFER-HEPU-S-GERH TAUI.

3. Golden Horus name. RENP-KHAU-S-HETEP-NETERU

4. Nesu bat name. NEB-KHEPERU-RA

5. Son of Ra name. TUTANKHAMEN

In some cases the cartouche of the nomen contains the signs which mean "governor of Anu of the South" (i.e., Hermonthis). When Tutankhaten ascended the throne he changed his name to Tutankhamen, i.e., "Living image of Amen."

Our chief authority for the acts of Tutankhamen is the stele in Cairo already referred to, and from the text, which unfortunately is mutilated in several places, we can gain a very good idea of the state of confusion that prevailed in Egypt when he ascended the throne. The hieroglyphs giving the year in which the stele was dated are broken away. The first lines give the names and titles of the king, who says that he was beloved of Amen-Ra, the great god of Thebes, of Temu and Ra-Heraakhuti, gods of Anu (Heliopolis), Ptah of Memphis, and Thoth, the Lord of the "words of god" (i.e., hieroglyphs and the sacred writings). He calls himself the "good son of Amen, born of Kamutef," and says that he sprang from a glorious seed and a holy egg, and that the god Amen himself had begotten him. Amen built his body, and fashioned him, and perfected his form, and the Divine Souls of Anu were with him from his youth up, for they had decreed that he was to be an eternal king, and an established Horus, who would devote all his care and energies to the service of the gods who were his fathers.

These statements are of great interest, for when understood as the king meant them to be understood, they show that his accession to the throne of Egypt was approved of by the priesthoods of Heliopolis, Memphis, Hermopolis and Thebes. Whatever sympathy he may have possessed for the Cult of Aten during the lifetime of Amenhetep IV had entirely disappeared when he set up his great stele at Karnak, and it is quite clear that he was then doing his utmost to fulfil the expectations of the great ancient priesthoods of Egypt.

The text continues: He made to flourish again the monuments which had existed for centuries, but which had fallen into ruin [during the reign of Aakhunaten]. He put an end to rebellion and disaffection. Truth marched through the Two Lands [which he established firmly]. When His Majesty became King of the South the whole country was in a state of chaos, similar to that in which it had been in primeval times (i.e., at the Creation). From Abu (Elephantine) to the Swamps [of the Delta] the properties of the temples of the gods and goddesses had been [destroyed], their shrines were in a state of ruin and their estates had become a desert. Weeds grew in the courts of the temples. The sanctuaries were overthrown and the sacred sites had become thoroughfares for the people. The land had perished, the gods were sick unto death, and the country was set behind their backs.

The state of general ruin throughout the country was, of course, largely due to the fact that the treasuries of the great gods received no income or tribute on any great scale from the vassal tribes of Palestine and Syria. It is easy to understand that the temple buildings would fall into ruin, and the fields go out of cultivation when once the power of the central authority was broken. Tutankhamen next says that if an envoy were sent to Tchah (Syria) to broaden the frontiers of Egypt, his mission did not prosper; in other words, the collectors of tribute returned empty-handed because the tribes would not pay it. And it was useless to appeal to any god or any goddess, for there was no reply made to the entreaties of petitioners. The hearts of the gods were disgusted with the people, and they destroyed the creatures that they had made. But the days wherein such things were passed by, and at length His Majesty ascended the throne of his father, and began to regulate and govern the lands of Horus, i.e., the temple-towns and their estates. Egypt and the Red Land (i.e., Desert) came under his supervision, and every land greeted his will with bowings of submission.

The text goes on to say that His Majesty was living in the Great House which was in Per-Aakheperkara. This palace was probably situated either in a suburb of Memphis or in some district at no great distance from that city. (Some think that it was in or quite near Thebes.) Here "he reigned like Ra in heaven," and he devoted him self to the carrying out of the "plan of this land." He pondered deeply in his mind on his courses of action, and communed with his own heart how to do the things that would be acceptable to the people. It was to be expected that, when once he had discarded Aten and all his works, he would have gone and taken up his abode in Thebes, and entered into direct negotiations with the priests of Amen. In other words, Tutankhamen was not certain as to the kind of reception he would meet with at Thebes, and therefore he went northwards, and lived in or near Memphis. Whilst here "he sought after the welfare of father Amen," and he cast a figure of his "august emanation," in gold, or silver-gold. Moreover, he did more than had ever been done before to enhance the power and splendour of Amen. The text unfortunately gives no description of the figure of Amen which he made in gold, but a very good idea of what it was like maybe gained from the magnificent solid gold figure of the god that is in the Carnarvon Collection at Highclere Castle, and was exhibited at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1922. A handsome silver figure of Amen-Ra, plated with gold, is exhibited in the British Museum (Fifth Egyptian Room, Table-case I, No. 42). This must have come from a shrine of the god. He next fashioned a figure of "Father Amen" on thirteen staves, a portion of which was decorated with gold tcham (i.e., gold or silver-gold), lapis lazuli and all kinds of valuable stones; formerly the figure of Amen only possessed eleven (?) staves. He also made a figure of Ptah, south of his wall, the Lord of Life, and a portion of this likewise was decorated with gold or silver-gold, lapis lazuli, turquoises and all kinds of valuable gems. The figure of Ptah, which originally stood in the shrine in Memphis, only possessed six (?) staves. Besides this, Tutankhamen built monuments to all the gods, and he made the sacred images of them of real tcham metal, which was the best produced. He built their sanctuaries anew, taking care to have durable work devoted to their construction; he established a system of divine offerings, and made arrangements for the maintenance of the same. His endowments provided for a daily supply of offerings to all the temples, and on a far more generous scale than was originally contemplated.

He introduced or appointed libationers and ministrants of the gods, whom he chose from among the sons of the principal men in their villages, who were known to be of good reputation, and provided for their increased stipends by making gifts to their temples of immense quantities of gold, silver, bronze and other metals. He filled the temples with servants, male and female, and with gifts which had formed part of the booty captured by him. In addition to the presents which he gave to the priests and servants of the temples, he increased the revenues of the temples, some twofold, some threefold and others fourfold, by means of additional gifts of tcham metal, gold, lapis lazuli, turquoises, precious stones of all kinds, royal cloth of byssus, flax-linen, oil, unguents, perfumes, incense, ahmit and myrrh. Gifts of "all beautiful things" were given lavishly by the king. Having re-endowed the temples, and made provision for the daily offerings and for the performance of services which were per-formed every day for the benefit of the king, that is to say, himself, Tutankhamen made provision for the festal processions on the river and on the sacred lakes of the temples. He collected men who were skilful in boat-building, and made them to build boats of new acacia wood of the very best quality that could be obtained in the country of Negau. Many parts of the boats were plated with gold, and their effulgence lighted up the river.

The information contained in the last two paragraphs enables us to understand the extent of the ruin that had fallen upon the old religious institutions of the country through the acts of Aakhunaten. The temple walls were mutilated by the Atenites, the priesthoods were driven out, and all temple properties were confiscated and applied to the propagation of the cult of Aten. The figures of the great gods that were made of gold and other precious metals in the shrines were melted down, and thus the people could not consult their gods in their need, for the gods had no figures wherein to dwell, even if they wished to come upon the earth. There were no priests left in the land, no gods to entreat, no funeral ceremonies could be performed, and the dead had to be laid in their tombs without the blessing of the priests.

During this period of religious chaos, which obtained throughout the country, a number of slaves, both male and female, and singing men, shemaiu, and men of the acrobat class had been employed by the Atenite king to assist in the performance of his religious services, and at festivals celebrated in honour of Aten. These Tutankhamen "purified" and transferred to the royal palace, where they performed the duties of servants of some kind in connection with the services of all the "father-gods." This treatment by the king was regarded by them as an act of grace, and they were exceedingly content with their new positions. The concluding lines of the stele tell us little more than that the gods and goddesses of Egypt rejoiced once more in beholding the performance of their services, that the old order of worship was reestablished, and that all the people of Egypt thanked the king for his beneficent acts from the bottom of their hearts. The gods gave the king life and serenity, and by the help of Ra, Ptah and Thoth he administered his country with wisdom, and gave righteous judgments daily to all the people.

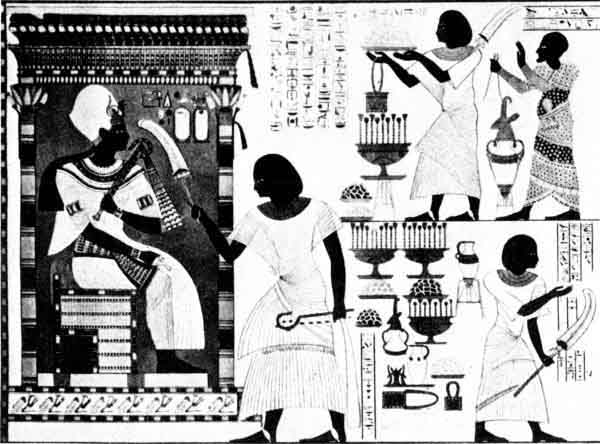

In line 18 on the Stele of Tutankhamen it is stated that the gifts made by the king to the priests and temples were part of the booty which His Majesty had captured from conquered peoples This suggests that even during his short reign of from eight to ten years he managed to make raids --they cannot be called wars--in the countries which his predecessors had conquered and made dependencies of Egypt. The truth of his statement is fully proved by the pictures and inscriptions found in the tomb of Hui in Western Thebes. This officer served in Nubia under Amenhetep IV, and as a reward for his fidelity and success the king made him Prince of Kesh (Nubia), and gave him full authority to rule from Nekhen, the modern Al-kab, about 50 miles south of Thebes, to Nest-Taui1 or Napata (Jabal Barkal), at the foot of the Fourth Cataract. During the reign of Tutankhamen Hui returned from Nubia to Thebes, bringing with him large quantities of gold, both in the form of rings and dust, vessels of gold and silver, bags full of precious stones, Sudani beds, couches, chairs of state, shields and a chariot.2 With these precious objects came the shekh of Maam, the shekh of Uait, the sons of all the principal chiefs on both sides of the river from Buhen (Wadi Halfah) to Elephantine, and a considerable number of slaves. Hui and his party arrived in six boats, and when all the gifts were unloaded they were handed over to Tutankhamen's officials, who had gone to receive them. It is not easy to decide whether this presentation of the produce of Nubia by Hui was an official delivery of tribute due to Tutankhamen, or a personal offering to the new king of Egypt. If Hui was appointed Viceroy of Kesh by Amenhetep IV or his father, it is possible that he was an adherent of the cult of Aten.

Plate I.

Hui presenting tribute and gifts from vassal peoples to Tutankhamen.

From Lepsius, Denkmäler III, 117

Plate II.

Red granite lion with an inscription on the base stating that it was made by Tutankhamen. It was dedicate by him to the temple of Sulb, in the Third Cataract in the Egyptian Sudan, when he "restored the monuments of his father, Amenhetep III. British Museum, Southern Egyptian Gallery, No. 431.

In this case, his gifts to Tutankhamen were probably personal, and were offered to him by Hui with the set purpose of placating the restorer of the cult of Amen. Be this as it may, the gold and silver and precious stones from Nubia were most acceptable to the king, for they supplied him with means for the re-endowment of the priests and the temples.

Egyptologists, generally, have agreed that the scenes in Hui's tomb representing the presentation of gifts from Nubia have a historical character, and that we may consider that Tutankhamen really exercised rule in Nubia. But there are also painted on the walls scenes in which the chiefs and nobles of Upper Retennu (Syria) are presenting the same kinds of gifts to Tutankhamen, and these cannot be so easily accepted as being historical in character. In his great inscription, Tutankhamen says explicitly that during the reign of Aakhunaten it was useless to send missions to Syria to "enlarge the frontiers of Egypt," for they never succeeded in doing so. But he does not say that he himself did not send missions, i.e., make raids, into some parts of Phoenicia and Syria, and it is possible that he did. It is also possible that some of the Syrian chiefs, hearing of the accession of a king who was following the example of Thothmes III and honouring Amen, sent gifts to him with the view of obtaining the support of Egyptian arms against their foes.

Exactly when and how Tutankhamen died is not known, and his age at the time of his death cannot be stated. No tomb of his has been found in the mountains of Tall al-'Amarnah, and, up to the present, there is no evidence that he had a tomb specially hewn for him in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. During the course of his excavations in this Valley, Mr. Theodore Davis found a tomb which he believed to be that of Tutankhamen.1 In it there was a broken box containing several pieces of gold leaf stamped with the names of Tutankhamen and his wife Ankhsenamen, etc. In a pit some distance from this tomb he discovered what he took to be the débris from a tomb, such as dried wreaths of leaves and flowers. The cover of a very large jar, which had been broken, was wrapped up in a cloth on which was inscribed the name of Tutankhamen. One of the most beautiful objects found by Davis was the little blue glazed funerary vase which is figured on plate XCII of this book. It was discovered in a sort of hiding place under a large rock, and bears the inscription "Beautiful god, Neb-kheperu Ra, giver of life". These facts certainly suggest that Davis found a tomb of Tutankhamen.

The objects in the British Museum that bear the name of Tutankhamen are few, the largest and most important being the granite lion which he placed in the temple built by Amenhetep III at Sulb (the "Soleb" of Lepsius), about half-way up the Third Cataract on the left or west bank. Several scarabs2 and a bead bearing his prenomen or nomen are exhibited in Table-Case B. (Fourth Egyptian Room), and also the fragment of a I model of a boomerang in blue glazed faience in Wall-Case 225 (Fifth Egyptian Room), No. 54822. Two fine porcelain tubes for stibium, or eye-paint, are exhibited in Wall-Case 272 (Sixth Egyptian Room). The one (No. 27376) has a dark bluish green colour and is inscribed "Beautiful god, Lord of the Two Lands, Lord of Crowns, Neb-kheperu-Ra,

giver of life for ever" and the other (No. 2573), which is white in colour, is inscribed with the names of his wife and himself. A writing palette bearing the king's prenomen1 was found at Kurnah during the time of the French Expedition, and this and the other objects mentioned above suggest that the royal tomb was being plundered during the early years of the XIXth century.

An interesting mention is made of Tutankhamen in one of the tablets from Boghaz Keui, and it suggests that communications passed more or less frequently between the kings of the Hittites at that period and the kings of Egypt. The document is written in cuneiform characters2 in the Hittite language, and states that the Queen of Egypt, called Da-kha-mu-un wrote to the father of the reigning Hittite king to tell him that her husband Bi-ib-khu-ruri-ya-ash was dead, and that she had no son, and that she wanted one, and she asked him to send to her one of his many sons, and him she would make her husband.3 Now Bibkhururiyaash is nothing more nor less than a transcription of NEB-KHEPERU-RA, the prenomen of king Tutankhamen.

Footnotes

1:1 See Mariette, Abydos, Paris, 1880, tom. II, pl. 40N.

2:1 This name means "Her life is of Aten" (i.e., of the Solar Disk).

2:2 See Aegyptische Zeitschrift, Bd. 38, 1900, pp. 112-114.

3:1 See Annales du Service, Vol. V, 1905, p. 192; Recueil de Travaux, Vol. XXIX, 1907, pp. 162-173.

10:1 This is a name of Thebes, but it was also applied to the town of Napata, where the great temple of Amen-Ra of Nubia was situated.

10:2 See the drawing published by Lepsius, Denkmäler III, pl. 116-118.

12:1 See Davis-Maspero-Daressy, The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touat-ankhamanou, London, 1912.

12:2 See Hall, H. R., Catalogue of Egyptian Scarabs, London, 1913, Nos. 1968-1972, pp. 197, 198.

13:1 This is the legend as printed in Champollion, Monuments, tom. II, pl. CXCI bis No. 2.

13:2 For the text see Keilschrift aus Boghazkoï, Heft V, No. 6. Rev. III, 11. 7-13.

13:3 See Dr. F. Hrosny, Die Lösung des Hethitischen Problems, in the Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft, December, 1915, No. 56, p. 36.