The Evolution Of The Dragon By G. Elliot Smith

M.A., M.D., F.R.S.

CHAPTER III. THE BIRTH OF APHRODITE.*

1 An elaboration of a lecture delivered at the John Rylands Library, on 14 November, 1917.

IT may seem ungallant to discuss the birth of Aphrodite as part of the story of the evolution of the dragon. But the other chapters of this book, in which frequent references have been made to the early history of the Great Mother, have revealed how vital a part she played in the development of the dragon. The earliest real dragon was Tiamat, one of the forms assumed by the Great Mother ; and an even earlier prototype was the lioness (Sekhet) manifestation of Hathor.

Thus it becomes necessary to enquire more fully (than has been done in the other chapters) into the circumstances of the Great Mother's birth and development, and to investigate certain aspects of her ontogeny to which only scant attention has been paid in the preceding pages.

Several reasons have led me to select Aphrodite from the vast legion of Great Mothers for special consideration, in spite of high specialization in certain directions the Greek goddess of love retains in greater measure than any of her sisters some of the most primitive associations of her original parent. Like vestigial structures in biology, these traits afford invaluable evidence, not only of Aphrodite's own ancestry and early history, but also of that of the whole family of goddesses of which she is only a specialized type. For Aphrodite's connexion with shells is a survival of the circumstances which called into existence the first Great Mother and made her not only the Creator of mankind and the universe, but also the parent of all deities, as she was historically the first to be created by human inventiveness. In this lecture I propose to deal with the more general aspects of the evolution of all these daughters of the Great Mother nut I have used Aphrodite's name in the title because her shell- associations can be demonstrated more clearly and definitely than those of any of her sisters.

In the past a vast array of learning has been brought to bear upon the problems of Aphrodite's origin ; but this effort has, for the most part, been characterized by a narrowness of vision and a lack of adequate appreciation of the more vital factors in her embryological history. In the search for the deep human motives that found specific expression in the great goddess of love, too little attention has been paid to primitive man's psychology, and his persistent striving for an elixir of life to avert the risk of death, to renew youth and secure a continuance of existence after death. On the other hand, the possibility of obtaining any real explanation has been dashed aside by most scholars, who have been content simply to juggle with certain stereotyped catch- phrases and baseless assumptions, simply because the traditions of classical scholarship have made these devices the pawns in a rather aimless game.

It is unnecessary to cite specific illustrations in support of this statement. Reference to any of the standard works on classical archaeology, such as Roscher's "Lexicon,"will testify to the truth of my accusation. In her "Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion "Miss Jane Harrison devotes a chapter (VI) to "The Making of a Goddess,"and discusses ". But she strictly observes the traditions of the classical method ; and assumes that the meaning of the myth of Aphrodite's birth from the sea - the germs of which are at least fifty centuries old - can be decided by the omission of any representation of the sea in the decoration of a pot made in the fifth century B.C. !

But apart from this general criticism, the lack of resourcefulness and open mindedness, certain more specific factors have deflected classical scholars from the true path. In the search for the ancestry of Aphrodite, they have concentrated their attention too exclusively upon the Mediterranean area and Western Asia, and so ignored the most ancient of the historic Great Mothers, the African Hathor, with whom (as Sir Arthur Evans* clearly demonstrated more than fifteen years ago) the Cypriote goddess has much closer affinities than with any of her Asiatic sisters. Yet no scholar, either on the Greek or Egyptian side, has seriously attempted to follow up this clue and really investigate the nature of the connections between Aphrodite and Hathor, and the history of the development of their respective specializations of functions.1

1 "Mycenaean Tree and Pillar Cult,"p. 52. Compare also A. E. W. Budge, "The Gods of the Egyptians,"Vol. I, p. 435.

* With a strange disregard of Sir Arthur Evans's " Mycenaean Tree and Pillar Cult,"Mr. H. R. Hall makes the following remarks in his "AEgean Archaeology "(p. 150): "The origin of the goddess Aphrodite has long been taken for granted. It has been regarded as a settled fact that she was Semitic, and came to Greece from Phoenicia or Cyprus. But the new discoveries have thrown this, like other received ideas, into the melting- pot, for the Minoans Undoubtedly worshipped an Aphrodite. We see her, naked and with her doves, on gold plaques from one of the Mycenaean shaft-graves (Schuchhardt, Scfiliemann, Figs. 180, 181), which must be as old as the First Late Minoan period (c. 1600-1500 B.C.), and - not rising from the foam, but sailing over it - in a boat, naked, on the lost gold ring from Mochlos. It is evident now that she was not only a Canaanitish-Syrian goddess, but was common to all the people of the Levant. She is Aphrodite-Paphia in Cyprus, Ashtaroth-Astarte in Canaan, Atargatis in Syria, Derketo in Philistria, Hathor in Egypt ; what the Minoans called her we do not know, unless she was Britomarlis. She must take her place by the side of Rhea-Diktynna in the Minoan pantheon."

But some explanation must be given for my temerity in venturing to invade the intensively cultivated domains of Aphrodite "with a mind undebauched by classical learning ". I have already explained how the study of Libations and Dragons brought me face to face with the problems of the Great Mother's attributes. At that stage of the enquiry two circumstances directed my attention specifically to Aphrodite. Mr. Wilfrid Jackson was collecting the data relating to the cultural uses of shells, which he has since incorporated in a book. 2

2 "Shells as Evidence of the Migration of Early Culture."

As the results of his search accumulated, the fact soon emerged that the original Great Mother was nothing more than a cowry-shell used a life-giving amulet ; and that Aphrodite's shell-associations were survival of the earliest phase in the Great Mother's history.

At this psychological moment Dr. Rendel Harris claimed that Aphrodite was a personification of the mandrake. But the magical attributes of the mandrake, which he claimed to have been responsible for converting the amulet into a goddess, were identical with those which Blackson's investigations had previously led me to regard as the reasons for deriving Aphrodite from the cowry. The mandrake was clearly a surrogate of the shell or vice versa."The problem to be solved was to decide which amulet was responsible for suggesting the process of life-giving. The goddess Aphrodite was closely related to Cyprus ; the mandrake was a magical plant there ; and the cowry is so intimately associated with the island as to be called Cypraea. So far as is known, however, the shell-amulet is vastly more ancient than the magical reputation of the plant. Moreover, we know why the cowry was regarded as feminine and accredited with life-giving attributes. There are no such reasons for assigning life-giving powers or the female sex to the mandrake. The claim that its magical properties are due to the fancied resemblance of its root to a human being is wholly untenable.3 The roots of many plants are at least as manlike ; and, even if this character was the exclusive property of the mandrake, how does it help to explain the remarkable repertory of quite arbitrary and fantastic properties and the female sex assigned to the plant? Sir James Frazer's claim that "such beliefs and practices illustrate the primitive tendency to personify nature "4 is a gratuitous and quite irrelevant assumption, which offers no explanation whatsoever of the specific and arbitrary nature of the form assumed by the personification. But when we investigate the historical development of the peculiar attributes of the cowry-shell, and appreciate why and how they were acquired, any doubt as to the source from which the mandrake contained its "magic "is removed ; and with it the fallacy of Sir James Frazer's wholly unwarranted claims is also exposed.

1 "The Ascent of Olympus."

2 A striking confirmation of the fact that the mandrake is really a surrogate of the cowry is afforded by the practice in modern Greece of using the mandrake earned in a leather bag in the same way (and for the same magical purpose as a love philtre) as the Baganda of East Africa use the cowry (in a leather bag) at the present time.

3 Old Gerade was frank enough to admit that he " never could perceive shape of man or woman "(quoted by Rendel Harris, op. cit., p. 110).

4 "Jacob and the Mandrakes,"Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol. VIII, p. 22.

It is not without interest to note that on the Mochlos ring the goddess is sailing in a papyrus float of Egyptian type, like the moon-goddess in her crescent moon.

The association of this early representative of Aphrodite with doves is of special interest in view of Highnard's attempt ("Le Mythe de Venus,"Annales du Musée Guimet, T. 1, 1880, p. 23) to derive the name of "la déesse a la colombe "from the Chaldean and Phoenician fhrit or phrut meaning "a dove ".

Mr. Hall might have extended his list of homologues to Mesopotamia, Iran, and India, to Europe and Further Asia, to America, and, in fact, every part of the world that harbours goddesses.

If we ignore Sir James Frazer's naive speculations we can make use of the compilations of evidence which he makes with such remark- able assiduity. But it is more profitable to turn to the study of the remarkable lectures which Dr. Rendel Hams has been delivering in this room l during the last few years. Our genial friend has been cultivating his garden on the slopes of Olympus," and has been plucking the rich fruits of his ripe scholarship and nimble wit. At the same time, with rougher implements and cruder methods, I have been burrowing in the depths of the earth, trying to recover information concerning the habits and thoughts of mankind many centuries before Dionysus and Apollo, and Artemis and Aphrodite, were dreamt of.

In the course of these subterranean gropings no one was more surprised than I was to discover that I was getting entangled in the roots of the same plants whose golden fruit Dr. Rendel Hams was gathering from his Olympian heights. But the contrast in our respective points of view was perhaps responsible for the different appearance the growths assumed.

To drop the metaphor, while he was searching for the origins of the deities a few centuries before the Christian era began, I was finding their more or less larval forms flourishing more than twenty centuries before the commencement of his story. For the gods and goddesses of his narrative were only the thinly disguised representatives of much more ancient deities decked out in the sumptuous habiliments of Greek culture.

In his lecture on Aphrodite, Dr. Rendel Harris claimed that the goddess was a personification of the mandrake ; and I think he made out a good prima facie case in support of his thesis. But other scholars have set forth equally valid reasons for associating Aphrodite with the argonaut, the octopus, the purpura, and a variety of other shells, both univalves and bivalves.

The goddess has also been regarded as a personification of water, the ocean, or its foam.1 Then again she is closely linked with pigs, lions, deer, goats, rams, dolphins, and a host of other creatures, not forgetting the dove, the swallow, the partridge, the sparling, the goose, and the swan."2

1 The well-known circumstantial story told in Hesiod's theogony.

3 Sir James Frazer's claim that the incident of the ass in a late Jewish story of Jacob and the mandrakes (pp. cit., p. 20) "helps us to understand the function of the dog,"is quite unsupported. The learned guardian of the Golden Bough does not explain how it helps us to understand.

The mandrake theory does not explain, or give adequate recognition to, any of these facts. Nor does Dr. Rendel Harris suggest why it is so dangerous an operation to dig up the mandrake which he identifies with the goddess, or why it is essential to secure the assist ance of a dogs in the process. The explanation of this fantastic fable gives an important clue to Aphrodite's antecedents.

THE SEARCH FOR THE ELIXIR OF LIFE. BLOOD AS LIFE

In delving into the remotely distant history of our species we can not fail to be impressed with the persistence with which, throughout the whole of his career, man (of the species sapiens) has been seeking4 for an elixir of life, to give added "vitality "to the dead (whose existence was not consciously regarded as ended), to prolong the days of active life to the living, to restore youth, and to protect his own life from all assaults, not merely of time, but also of circumstance. In other words, the elixir he sought was something that would bring "good luck "in all the events of his life and its continuation. Most of the amulets, even of modern times, the lucky trinkets, the averters of the "Evil Eye,"the practices and devices for securing good luck in love and sport, in curing bodily ills or mental distress, in attaining material prosperity, or a continuation of existence after death, are survivals of this ancient and persistent striving after those objects which our earliest forefathers called collectively the "givers of life ".

From statements in the earliest literature that has come down to us from antiquity, no less than from the views that still prevail among the relatively more primitive peoples of the present day, it is clear that originally man did not consciously formulate a belief in immortality.

It was rather the result of a defect of thinking, or as the modern psychologist would express it, an instinctive repression of the unpleasant idea that death would come to him personally, that primitive man refused to contemplate or to entertain the possibility of life coming to an end. So intense was his instinctive love of life and dread of physical damage as would destroy his body that man unconsciously avoided thinking of the chance of his own death: hence his belief in the continuance of life cannot be regarded as the outcome of an active process of constructive thought.

This may seem altogether paradoxical and incredible.

How, it may be asked, can man be said to repress the idea of death, if he instinctively refused to admit its possibility? How did he escape the inevitable process of applying to himself the analogy he might have been supposed to make from other men's experience and recognize that he must die?

Man appreciated the fact that he could kill an animal or another man by inflicting certain physical injuries on him. But at first he seems to have believed that if he could avoid such direct assaults upon himself, his life would flow on unchecked. When death does occur and the onlookers recognize the reality, it is still the practice among certain relatively primitive people to search for the man who has inflicted death on his fellow.

It would, of course, be absurd to pretend that any people could fail to recognize the reality of death in the great majority of cases. The mere fact of burial is an indication of this. But the point of difference between the views of these early men and ourselves, was the tacit assumption on the part of the former, that in spite of the obvious changes in his body (which made inhumation or some other procedure necessary) the deceased was still continuing an existence not unlike that which he enjoyed previously, only somewhat duller, less eventful and more precarious. He still needed food and drink, as he did be fore, and all the paraphernalia of his mortal life, but he was dependent upon his relatives for the maintenance of his existence.

Such views were difficult of acceptance by a thoughtful people, once they appreciated the fact of the disintegration of the corpse in the grave ; and in course of time it was regarded as essential for continued existence that the body should be preserved. The idea developed, that so long as the body of the deceased was preserved and there were restored to it all the elements of vitality which it had lost at death, the continuance of existence was theoretically possible and worthy of acceptance as an article of faith.

Let us consider for a moment what were considered to be elements of vitality by the earliest members of our species.1

1 Some of these have been discussed in Chapter I (" Incense and Libations ") and will not be further considered here.

From the remotest times man seems to have been aware of the fact that he could kill animals or his fellow men by means of certain physical injuries. He associated these results with the effusion of blood. The loss of blood could cause unconsciousness and death. Blood, therefore, must be the vehicle of consciousness and life, the material whose escape from the body could bring life to an end."

The first pictures painted by man, with which we are at present acquainted, are found upon the walls and roofs of certain caves in Southern France and Spain. They were the work of the earliest known representatives of our own species, Homo sapiens, in the phase of culture now distinguished by the name " Aurignacian ".

The animals man was in the habit of hunting for food are depicted. In some of them arrows are shown implanted in the animal's flank near the region of the heart ; and in others the heart itself is represented.

This implies that at this distant time in the history of our species, it was already realized how vital a spot in the animal's anatomy the heart was. But even long before man began to speculate about the functions of the heart, he must have learned to associate the loss of blood on the part of man or animals with death, and to regard the pouring out of blood as the escape of its vitality. Many factors must have contributed to the new advance in physiology which made the heart the centre or the chief habitation of vitality, volition, feeling, and knowledge.

Not merely the empirical fact, acquired by experience in hunting, of the peculiarly vulnerable nature of the heart, but perhaps also the knowledge that the heart contained life-giving blood, helped in developing the ideas about its functions as the bestower of life and consciousness.

The palpitation of the heart after severe exertion or under th influence of intense emotion would impress the early physiologist with the relationship of the heart to the feelings, and afford confirmation of his earlier ideas of its functions.

But whatever the explanation, it is known from the folk-lore Of even the most unsophisticated peoples that the heart was originally regarded as the seat of life, feeling, volition, and knowledge, and that the blood was the life-stream. The Aurignacian pictures in the caves of Western Europe suggest that these beliefs were extremely ancient.

The evidence at our disposal seems to indicate that not only were such ideas of physiology current in Aurignacian times, but also certain cultural applications of them had been inaugurated even then. The remarkable method of blood-letting by chopping off part of a finger seems to have been practised even in Aurignacian times.1

1 Sollas, op. cit., pp. 347 et seq.

If it is legitimate to attempt to guess at the meaning these early people attached to so singular a procedure, we may be guided by the ideas associated with this act in outlying corners of the world at the present time. On these grounds we may surmise that the motive underlying this, and other later methods of blood-letting, such as circumcision, piercing the ears, lips, and tongue, gashing the limbs and body, et cetera, was the offering of the life-giving fluid.

Once it was recognized that the state of unconsciousness or death was due to the loss of blood it was a not illogical or irrational procedure to imagine that offerings of blood might restore consciousness and life to the dead.2 If the blood was seriously believed to be the vehicle of feeling and knowledge, the exchange of blood or the offering of blood to the community was a reasonable method for initiating any one into the wider knowledge of and sympathy with his fellow-men.

2 The "redeeming blood"

Blood-letting, therefore, played a part in a great variety of ceremonies, of burial and of initiation, and also those of a therapeutic3 and, later, of a religious significance.

3 The practice of blood-letting for therapeutic purposes was probably first suggested by a confused rationalisation. The act of blood-letting was a means of healing ; and the victim himself supplied the vitalizing fluid !

But from Aurignacian times onwards, it seems to have been Emitted that substitutes for blood might be endowed with a similar potency.

The extensive use of red ochre or other red materials for packing around the bodies of the dead was presumably inspired by the idea that materials simulating blood-stained earth, were endowed with the same life-giving properties as actual blood poured out upon the ground in similar vitalizing ceremonies.

As the shedding of blood produced unconsciousness, the offering of blood or red ochre was, therefore, a logical and practical means of restoring consciousness and reinforcing the element of vitality which was diminished or lost in the corpse.

The common statement that primitive man was a fantastically irrational child is based upon a fallacy. He was probably as well endowed mentally as his modern successors ; and was as logical and rational as they are ; but many of his premises were wrong, and he hadn't the necessary body of accumulated wisdom to help him to correct his false assumptions.

If primitive man regarded the dead as still existing, but with a reduced vitality, it was a not irrational procedure on the part of the people of the Reindeer Epoch in Europe to pack the dead in red ochre (which they regarded as a surrogate of the life-giving fluid) to make good the lack of vitality in the corpse.

If blood was the vehicle of consciousness and knowledge, the exchange of blood was clearly a logical procedure for establishing communion of thought and feeling and so enabling an initiate to assimilate the traditions of his people.

If red carnelian was a surrogate of blood the wearing of bracelets or necklaces of this life-giving material was a proper means of warding off danger to life and of securing good luck.

If red paint or the colour red brought these magical results, it was clearly justifiable to resort to its use.

All these procedures are logical. It is only the premises that were erroneous.

The persistence of such customs in Ancient Egypt makes it possible for us to obtain literary evidence to support the inferences drawn from archaeological data of a more remote age. For instance, the red jasper amulet sometimes called the " girdle-tie of Isis,"was supposed to represent the blood of the goddess and was applied to the mummy "to stimulate the functions of his blood "1 or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it was intended to add to the vital substance which was so obviously lacking in the corpse.

1 Davies and Gardiner, "The Tomb of Amenemhet,"p. 112.

THE COWRY AS A GIVER OF LIFE

Blood and its substitutes, however, were not the only materials that had acquired a reputation for vitalizing qualities in the Reindeer Epoch. For there is a good deal of evidence to suggest that shells also were regarded, even in that remote time, as life-giving amulets.

If the loss of blood was at first the only recognized cause of death, the act of birth was clearly the only process of life-giving. The portal by which a child entered the world was regarded, therefore, not only as the channel of birth, but also as the actual giver of life.2 The large Red Sea cowry-shell, which closely simulates this "giver of life,"then came to be endowed by popular imagination with the same powers. Hence the shell was used in the same way as red ochre or carnelian: it was placed in the grave to confer vitality on the dead, and worn on bracelets and necklaces to secure good luck by using the "giver of life "to avert the risk of danger to life. Thus the general life-giving properties of blood, blood substitutes, and shells, came to be assimilated the one with the other.3

2 As it is still called in the Semitic languages. In the Egyptian Pyramid Texts there is a reference to a new being formed "by the vulva of Tefnut "(Breasted).

3 Many customs and beliefs of primitive peoples suggest that this correlation of the attributes of blood and shells went much deeper than the similarity of their use in burial ceremonies and for making necklaces and bracelets. The fact that the monthly effusion of blood in women ceased during pregnancy seems to have given rise to the theory, that the new life of the child was actually formed from the blood thus retained. The beliefs that grew up in explanation of the placenta form part of the system of interpretation of these phenomena: for the placenta was regarded as a mass of clotted blood (intimately related to the child which was supposed to be derived from part of the same material) which harboured certain elements of the child's mentality (because blood was the substance of consciousness).

At first it was probably its more general power of averting death or giving vitality to the dead that played the more obtrusive part in the magical use of the shell. But the circumstances which led to the development of the shell's symbolism naturally and inevitably conferred upon the cowry special power over women. It was the surrogate of the life-giving organ. It became an amulet to increase the fertility of women and to help them in childbirth. It was, therefore, worn by girls suspended from a girdle, so as to be as near as possible to the organ it was supposed to simulate and whose potency it was believed to be able to reinforce and intensify. Just as bracelets and necklaces of camelian were used to confer on either sex the vitalizing virtues of blood, which it was supposed to simulate, so also cowries, or imitations of them made of metal or stone, were worn as bracelets, neck laces, or hair-ornaments, to confer health and good luck in both sexes. But these ideas received a much further extension.

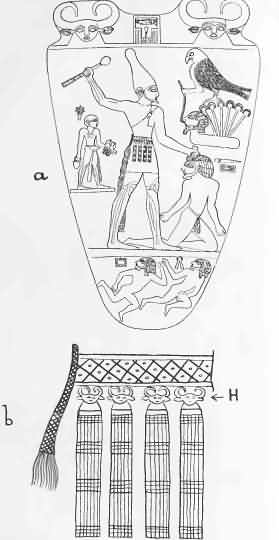

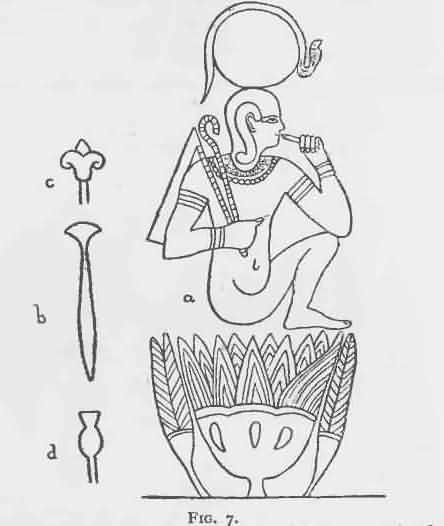

FIG. 18. -(a)

FIG. 18. -(a)

THE ARCHAIC Egyptian SLATE PALETTE OF NARMEK SHOWING, PERHAPS, THE KAKLIEST DESIGN OK HATHOK (AT THE UPPER CORNERS OK THE PALETTE) AS A WOMAN WITH COW'S HORNS AND EARS . THE PHARAOH IS WEARING A KILT FROM WHICH ARK SUSPENDED FOUR COW-HEADED HATHOR FIGURES IN PLACE OF THE COWRY-AMULETS OF MORE PRIMITIVE PEOPLES. THIS AFFORDS CORROBORATION OF THE VIEW 'THAT HATHOR ASSUMED THE FUNCTIONS ORIGINALLY ATTRIBUTED TO THE COWRY-SHELL.

(b)THE KING'S SPORRAN, WHERE HATHOR-HEADS (H) TAKE THE PLACE OF

THE COWRIES OF THE PRIMITIVE GIRDLE.

FIG. 19

FIG. 19

THE FRONT OF STELA B (FAMOUS FOR THE REALISTIC REPRESENTATIONS OF THE INDIAN ELEPHANT AT ITS UPPER CORNERS), ONE OF THE ANCIENT MAYA MONUMENTS AT CPPAN, CENTRAL AMERICA (AFTER MAUDSLAY'S PHOTOGRAPH AND DIAGRAM). -

THE GIRDLE OF THE CHIEF FIGURE IS DECORATED BOTH WITH SHELLS (OLIVA OR CONUS) AND AMULETS REPRESENTING HUMAN RACES CORRESPONDING TO THE HATHOR-HEADS ON THE NARMER PALETTE (FlG. l8).

As the giver of life, the cowry came to have attributed to it by some people definite powers of creation. It was not merely an amulet to increase fertility: it was itself the actual parent of mankind, the creator of all living things ; and the next step was to give these maternal functions material expression, and personify the cowry as an actual woman in the form of a statuette with the distinctly feminine characters grossly exaggerated ;1 and in the domain of belief to create the image of a Great Mother, who was the parent of the universe.

1 See S. Reinach, "Les Déesses Nues dans l'Art Oriental et dans l'Art Grec,"Revue Archéol., T. XXVI, 1895, p. 367. Compare also the figurines of the so-called Upper Palaeolithic Period in Europe.

Thus gradually there developed out of the cowry-amulet the conception of a creator, the giver of life, health, and good luck. This Great Mother, at first with only vaguely defined traits, was probably the first deity that the wit of man devised to console him with her watchful care over his welfare in this life and to give him assurance as to his fate in the future.

At this stage I should like to emphasize the fact that these beliefs had taken shape long before any definite ideas had been formulated as to the physiology of animal reproduction and before agriculture was practised.

Man had not yet come to appreciate the importance of vegetable fertility, nor had he yet begun to frame theories of the fertilizing powers of water, or give specific expression to them by creating the god Osiris in his own image.

Nor had he begun to take anything more than the most casual interest in the sun, the moon, and the stars. He had not yet devised a sky-world nor created a heaven. When, for reasons that I have already discussed, the theory of the fertilizing and the animating power of water was formulated, the beliefs concerning this element were assimilated with those which many ages previously had grown up in explanation of the potency of blood and shells. In addition to fertilizing the earth, water could also animate the dead. The rivers and the seas were in fact a vast reservoir of this animating substance. The powers of the cowry, as a product of the sea, were rationalized into an expression of the great creative force of the water.

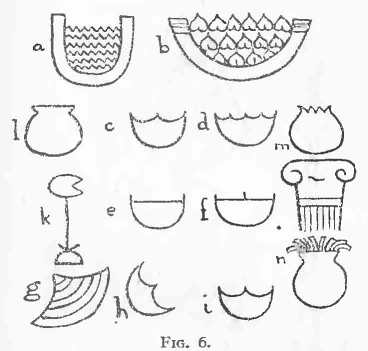

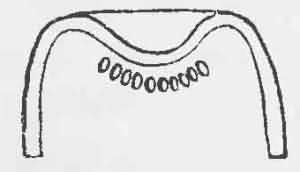

A bowl of water became the symbol of the fruitfulness of woman. Such symbolism implied that woman, or her uterus, was a receptacle into which the seminal fluid was poured and from which a new being emerged in a flood of amnionic fluid.

The burial of shells with the dead is an extremely ancient practice, for cowries have been found upon human skeletons of the so-called "Upper Palaeolithic Age "of Southern Europe.

At Laugerie-Basse (Dordogne) Mediterranean cowries were found arranged in pairs upon the body ; two pairs on the forehead, one near each arm, four in the region of the thighs and knees, and two upon each foot. Others were found in the Mentone caves, and are peculiarly important, because, upon the same stratum as the skeleton with which they were associated, was found part of a Cassis rufa, a shell whose habitat does not extend any nearer than the Indian Ocean.1

1 The literature relating to these important discoveries has been summarized by Wilfrid Jackson in his " Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture,"pp. 135-7.

These facts are very important. In the first place they reveal the great antiquity of the practice of burying shells with the dead, presumably for the purpose of "life-giving ". Secondly, they suggest the possibility that their magical value as givers of life may be more ancient than their specific use as intensifiers of the fertility of women. Thirdly, the association of these practices with the use of the shell Cassis indicates a very early cultural contact between the people living upon the North-Western shores of the Mediterranean in the Reindeer Age and the dwellers on the coasts of the Indian Ocean ; and the probability that these special uses of shells by the former were inspired by the latter.

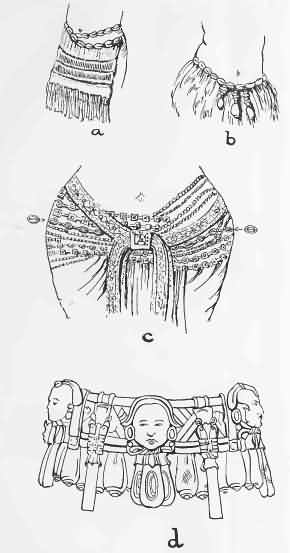

FIG. 20.

DIAGRAMS ILLUSTRATING THE FORM OF COWRY-BELTS WORN IN (a) EAST

AFRICA AND (b) OCEANIA RESPECTIVELY.

(c) ANCIENT INDIAN GIRDLE (FROM THE FIGURE OF SIRIMA DEVATA ON

THE BHARAT TOPR.), CONSISTING OF STRINGS OK PEARLS AND PRECIOUS

STONES, AND WHAT SEEM TO BE (FOURTH ROW FROM THE TOP) MODELS OF

COWRIES.

(d) THE COPAN GIRDLE (FROM FIG. 19) IN WHICH BOTH SHELLS AND

HEADS OF DEITIES ARE REPRESENTED. THE TWO OBJECTS SUSPENDED FROM

THE BELT BETWEEN THE HEADS RECALL HATHOR'S SISTRA.

This hint assumes a special significance when we first get a clear view of the more fully-developed shell-cults of the Eastern Mediterranean many centuries later. For then we find definite indications that the cultural uses of shells were obviously borrowed from the Erythraean area.

Long before the shell-amulet became personified as a woman the Mediterranean people had definitely adopted the belief in the cowry's ability to give life and birth.

THE ORIGIN OF CLOTHING

The cowry and its surrogates were supposed to be potent to confer fertility on maidens ; and it became the practice for growing girls to wear a girdle on which to suspend the shells as near as possible to the organ their magic was supposed to stimulate. Among many peoples "this girdle was discarded as soon as the girls reached maturity.

This practice probably represents the beginning of the history of clothing ; but it had other far-reaching effects in the domain of belief.

It has often been claimed that the feeling of modesty was not the reason for the invention of clothing, but that the clothes begat modesty.' This doctrine contains a certain element of truth, but is by no means the whole explanation. For true modesty is displayed by people who have never worn clothes.

Before mankind could appreciate the psychological fact that the wearing of clothing might add to an individual's allurement and enhance her sexual attractiveness, some other circumstances must have been responsible for suggesting the experiments out of which this empirical knowledge emerged. The use of a girdle (a) as a protection against danger to life, and (b) as a means of conferring fecundity on girls1 provided the circumstances which enabled men to discover that the sexual attractiveness of maidens, which in a state of nature was originally associated with modesty and coyness, was profoundly intensified by the artifices of clothing and adornment.

1 It is important to remember that shell-girdles were used by both sexes for general life-giving and luck-bringing purposes, in the funerary ritual of both sexes, in animating the dead or statues of the dead, to attain success in hunting, fishing, and head-hunting, as well as in games. Thus men also at times wore shells upon their belts or aprons, and upon their implements and fishing nets, and adorned their trophies of war and the chase with them. Such customs are found in all the continents of the Old World and also in America, as, for example, in the girdles of Conus- and Oliva-shells worn by the figures sculptured upon the Copan stelae. See, for example, Maudslay's pictures of stele N, Plate 82 (Biologia Central- Americana ; Archaeology) inter alia. But they were much more widely used by women, not merely by maidens, but also by brides and married women, to heighten their fertility and cure sterility, and by pregnant women to en sure safe delivery in child-birth. It was their wider employment by women that gives these shells their peculiar cultural significance.

Among people (such as those of East Africa and Southern Arabia) in which it was customary for unmarried girls to adorn them selves with a girdle, it is easy to understand how the meaning of the practice underwent a change, and developed into a device for enhancing their charms and stimulating the imaginations of their suitors.

Out of such experience developed the idea of the magical girdle as an allurement and a love-provoking charm or philtre. Thus Aphrodite's girdle acquired the reputation of being able to compel love. When Ishtar removed her girdle in the under-world reproduction ceased in the world. The Teutonic Brunhild's great strength lay in her girdle. In fact magic virtues were conferred upon most goddesses in every part of the world by means of a cestus of some sort.2 But the outstanding feature of Aphrodite's character as a goddess of love is intimately bound up with these conceptions which developed from the wearing of a girdle of cowries.

2 Witness the importance of the girdle in early Indian and American sculptures: in the literature of Egypt, Babylonia, Western Europe, and the Mediterranean area. For important Indian analogies and Egyptian parallel^ see Moret, " Mystéres Égyptiens,"p. 91, especially note 3. The magic girdle assumed a great variety of forms as the number of surrogates of the cowry increased. The mugwort (Artemisia) of Artemis was worn in the girdle on St. John's Eve (Rendel Harris, of. cit., p. 91): the people of Zante use vervain in the same way ; the people of France (Creuse et Corréres) rye-stalks ; Eve's fig-leaves ; in Vedic India the initiate wore the " cincture of Munga's herbs "; and Kali had her girdle of hands. Breasted, ("Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt,"p. 29) says : "In the oldest fragments we hear of Isis the great, who fastened on the girdle in Khemmis, when she brought her [censer] and burned incense before her son Horus ".

In the Biblical narrative, after Adam and Eve had eaten the for bidden fruit, "the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked ; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons,"or, as the Revised Version expresses it, "girdles". The girdle of fig-leaves, however, was originally a surrogate of the girdle of cowries: it was an amulet to give fertility. The consciousness of nakedness was part of the knowledge acquired as the result of the wearing of such girdles (and the clothing into which they developed), and was not originally the motive that impelled our remote ancestors to clothe themselves.

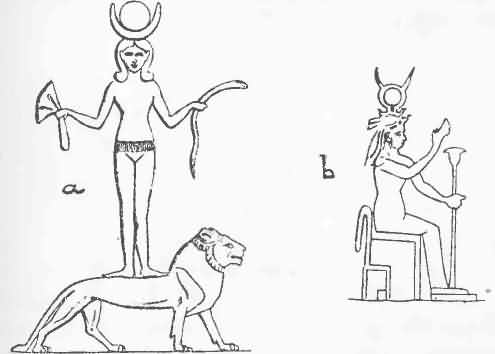

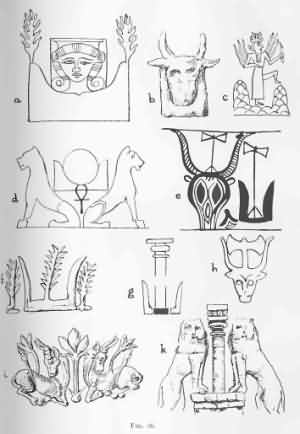

FlG. 4. - - TWO REPRESENTATIONS OF ASTARTE (QETBSH).

(a) The mother-goddess standing upon a lioness (which is her Sekhet form): she is wearing her girdle, and upon her head is the moon and the cow's horns, conventionalised so as to simulate the crescent moon. Her hair is represented ,n the conventional form which is sometimes used as Hathor's symbol. In her hands are the serpent and the lotus, which again are merely forms of the goddess herself.

(b) Another picture of Astarte (from Reseller's "Lexikon") holding the papyrus sceptre which at times is regarded as an animate form of the mother-goddess herself and as such a thunder weapon.

The use of fig-leaves for the girdle in Palestine is an interesting connecting link between the employment of the cowry and the man drake for similar purposes in the neighbourhood of the Red Sea and in Cyprus and Syria respectively (vide infra).

In Greece and Italy, the sweet basil has a reputation for magical properties analogous to those of the cowry. Maidens collect the plant and wear bunches of it upon their body or upon their girdles ; while married women fix basil upon their heads.1 It is believed that the odour of the plant will attract admirers: hence in Italy it is called Bacia-nicola. "Kiss me, Nicholas ".2

1 This distinction between the significance of the amulet when worn on the girdle and on the head (in the hair), or as a necklace or bracelet, is very widespread. On the girdle it usually has the significance of stimulating the individual's fertility: worn elsewhere it was intended to ward off danger to life, i.e. to give good luck. An interesting surrogate of Hathor's distinctive emblem is the necklace of golden apples worn by a priestess of Apollo (Rendel Harris, op. cit., p. 42).

2 De Gubernatis, "[Mythologie des Plantes,"Vol. II, p. 35.

In Crete it is a sign of mourning presumably because its life-pro longing attributes, as a means of conferring continued existence to the dead, have been so rationalized in explanation of its use at funerals.

On New Year's day in Athens boys carry a boat and people remark, "St. Basil is come from Caesarea".

PEARLS

During the chequered history of the Great Mother the attributes of the original shell-amulet from which the goddess was sprung were also changing and being elaborated to fit into a more complex scheme. The magical properties of the cowry came to be acquired by other Red Sea shells, such as Pterocera, the pearl oyster, conch shells, and others. Each of these became intimately associated with the moon.3 The pearls found in the oysters were supposed to be little moons, drops of the moon-substance (or dew) which fell from the sky into the gaping oyster. Hence pearls acquired the reputation of "shining by night,"like the moon from which they were believed to have come : and every surrogate of the Great Mother, whether plant, animal, mineral or mythical instrument, came to be endowed with the power of "shining by night ". But pearls were also regarded as the quintessence of the shell's life-giving properties, which were considered to be all the more potent because they were sky-given emanations of the moon-goddess herself. Hence pearls acquired the reputation of

being the "givers of life par excellence, an idea which found literal expression in the ancient Persian word margan (from mar, "giver"and gan, "life").

3 For the details see Jackson, op. cit., pp. 57-69. Both the shells and the moon were identified with the Great Mother. Hence they were homologized the one with the other.

This word has been borrowed in all the Turanian languages (ranging from Hungary to Kamskatckha), but also in the- non-Turanian speech of Western Asia, thence through Greek and Latin (margarita) to European languages.1 The same life-giving attributes were also acquired by the other pearl-bearing shells ; and at some subsequent period, when it was discovered that some of these shells could be used as trumpets, the sound produced was also believed to be life-giving or the voice of the great Giver of Life. The blast of the trumpet was also supposed to be able to animate the deity and restore his consciousness, so that he could attend to the appeals of supplicants. In other words the noise woke up the god from his sleep. Hence the shell-trumpet attained an important significance in early religious ceremonials for the ritual purpose of summoning the deity, especially in Crete and India, and ultimately in widely distant parts of the world. Long before these shells are known to have been used as trumpets, they were employed like the other Red Sea shells as "givers of life "to the dead in Egypt. Their use as trumpets was secondary.

1 Dr. Mingana has given me the following note: "It is very probable that the Graeco-Latin margarita, the Aramaeo-Syriac margarita, the Arabic margan, and the Turanian margan are derived from the Persian mar-gan, meaning both ' pearl ' and ' life,' or etymologically ' giver, owner, or possessor, of life '. The word gan, in Zend yan, is thoroughly Persian and is undoubtedly the original form of this expression."

And when it was discovered that purple dye could be obtained from certain of the trumpet-shells, the colouring-matter acquired the same life-giving powers as had already been conferred upon the trumpet and the pearls: thus it became regarded as a divine sub stance and as the exclusive property of gods and kings.

Long before, the colour red had acquired magic potency as a surrogate of life-giving blood ; and this colour-symbolism undoubtedly helped in the development of the similar beliefs concerning purple.

SHARKS AND DRAGONS

When the life-giving attributes of water were confused with the same properties with which shells had independently been credited long before, the shell's reputation was rationalized as an expression of the vital powers of the ocean in which the mollusc was born. But the same explanation was also extended to include fishes, and other denizens of the water, as manifestations of similar divine powers. In the lecture on " Dragons and Rain Gods"I referred to the identification of Ea, the Babylonian Osiris, with a fish . When the value of the pearl as the giver of life impelled men to incur any risks to obtain so precious an amulet, the chief dangers that threatened pearl-fishers were due to sharks. These came to be regarded as demons guarding the treasure-houses at the bottom of the sea. Out of these crude materials the imaginations of the early pearl-fishers created the picture of wonderful submarine palaces of Naga kings in which vast wealth, not merely of pearls, but also of gold, precious stones, and beautiful maidens (all of them "givers of life,"vide infra, p. 224), were placed under the protection of shark-dragons.1 The conception of the pearl (which is a surrogate of the life-giving Great Mother) guarded by dragons is linked by many bonds of affinity with early Erythraean and Mediterranean beliefs. The more usual form of the story, both in Southern Arabian legend and in Minoan and Mycenaean art, represents the Mother Goddess incarnate in a sacred tree or pillar with its protecting dragons in the form of serpents or lions, or a variety of dragon-surrogates, either real animals, such as deer or cattle, or composite monsters (Fig. 26).2

1 In Eastern Asia (see, for example, Shinji Nishimura, "The Hisago- Bune,"Tokio, 1918, published by the Tokio Society of Naval Architects, p. 18, where the dragon is identified with the want, which can be either a crocodile or a shark) ; in Oceania (L. Frobenius, "Das Zeitalter des Son nengottes,"Bd. L, 1904, and C. E. Fox and F. H. Drew, "Beliefs and Tales of San Cristoval,"Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. XLV, 1915, p. 140) ; and in America (see Thomas Gann, "Mounds in Northern Honduras,"Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1897-8, Part II, p. 661) the dragon assumes the form of a shark, a crocodile, or a variety of other animals.

2 In Western mythology the dragon guarding the

fruit-bearing tree of life is also identified with the Mother of

Mankind (Campbell, "Celtic Dragon Myth,"pp. xli and 18). Thus the

tree and its defender are both surrogates of the Great Mother.

When Eve ate the apple from the tree of Paradise she was

committing an act of cannibalism, for the plant was only another

form of herself. Her "sin "consisted in aspiring to attain the

immortality which was the exclusive privilege of the gods. This

incident is analogous to that found in the Indian tales where

mortals steal the amrita. By Eve's sin "death came into the world

"for the paradoxical reason that she had eaten the food of the

gods which gives immortality. The punishment meted out to her by

the Almighty seems to have been to inhibit the life-giving and

birth-facilitating action of the fruit of immortality, so that

she and all her progeny were doomed to be mortal and to suffer

the pangs of child-bearing.

There was a widespread belief among the ancients that ceremonies

in connexion with the gods must (to be efficacious) be done in

the reverse of the usual human way (Hopkins, "Religions of

India,"p. 201). So also an act which gives immortality to the

gods, brings death to man. The full realization of the fact that

man was mortal imposed upon the early theologians the necessity

of explaining the immortality of the gods. The elixir of life was

the food of the gods that conferred eternal life upon them. By

one of those paradoxes so dear to the maker of myths this same

elixir brought death to man.

2 'L Sir Arthur Evans, "Mycenaean Tree and Pillar Cult,"op. cit. supra: W. Hayes Ward, "The Seal Cylinders of Western Asia,"op. cit.: and Robertson Smith, "The Religion of the Semites,"p. 133: "In Hadramant it is still dangerous to touch the sensitive mimosa, because the spirit that resides in the plant will avenge the injury ". When men interfere with the incense trees it is reported: "the demons of the place flew away with doleful cries in the shape of white serpents, and the intruders died soon afterwards ".

There are reasons for believing that these stories were first invented somewhere on the shores of the Erythraean Sea, probably in Southern Arabia. The animation of the incense-tree by the Great Mother, for the reasons which I have already expounded,1 formed the link of her identification with the pearl, which probably acquired its magical reputation in the same region.

1 Vide supra, p. 38.

"In the Persian myth, the white Haoma is a divine tree, growing in the lake Vourukasha: the fish Khar-mâhi circles protectingly around it and defends it against the toad Ahriman. It gives eternal life, children to women, husbands to girls, and horses to men. In the Min ókhired the tree is called ' the préparer of the corpse "(Spiegel, "Eran. Altertumskunde,"II, 115 -quoted by Jung, "Psychology of the Unconscious,"p. 532). The idea of guarding the divine tree' by dragons was probably the result of the transference to that particular surrogate of the Great Mother of the shark-stories which origin ated from the experiences of the seekers after pearls, her other representatives.

There are many other bits of corroborative evidence to suggest that these shell-cults and the legends derived from them were actually transmitted from the Red Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean. Nor is it surprising that this should have happened, when it is recalled that Egyptian sailors were trafficking in both seas long before the Pyramid Age, and no doubt carried the beliefs and the legends of one region to the other. I have already referred to the adoption in the Mediterranean area of the idea of the dragon-protectors of the tree- and pillar- forms of the Great Mother, and suggested that this was merely a garbled version of the pearl-fisher's experience of the dangers of attacks by sharks. But the same legends also reached the Levant in a less modified form, and then underwent another kind of transformation (and confusion with the tree-version) in Cyprus or Syria.

As the shark would be a not wholly appropriate actor in the Mediterranean, its role is taken by its smaller Selachian relative, the dog-fish. In the notes on Pliny's Natural History, Dr. Bostock and Mr. H. T. Riley 1 refer to the habits of dog-fishes ("Canes marini"), and quote from Procopius ("De Bell. Pers."B. I, c. 4) the following "wonderful story in relation to this subject ": "Sea-dogs are wonderful admirers of the pearl-fish, and follow them out to sea. ... A certain fisherman, having watched for the moment when the shell-fish was deprived of the attention of its attendant sea-dog, . . . seized the shell-fish and made for the shore. The sea-dog, however, was soon aware of the theft, and making straight for the fisherman, seized him. Finding himself thus caught, he made a last effort, and threw the pearl-fish on shore, immediately on which he was torn to pieces by its protector."2

1 Bonn's Edition, 1855, Vol. II, p. 433.

2 A Cretan scene depicts a man attacking a dog-headed sea-monster (Mackenzie, op. cit., "Myths of Crete,"p. 139).

Though the written record of this story is relatively modern the incident thus described probably goes back to much more ancient times. It is only a very slightly modified version of an ancient narrative of a shark's attack upon a pearl-diver.

For reasons which I shall discuss in the following pages, the r óle of the cowry and pearl as representatives of the Great Mother was in the Levant assumed by the mandrake, just as we have already seen the Southern Arabian conception of her as a tree adopted in Mycenaean lands. Having replaced the sea-shell by a land plant it became necessary, in adapting the legend, to substitute for the "sea-dog "some land animal. Not unnaturally it became a dog. Thus the story of the dangers incurred in the process of digging up a mandrake assumed the well-known form.1 The attempt to dig up the mandrake was said to be fraught with great danger. The traditional means of circumventing these risks has been described by many writers, ancient and modern, and preserved in the folk-lore of most European and western Asiatic countries. The story as told by Josephus is as follows: "They dig a trench round it till the hidden part of the root is very small, then they tie a dog to it, and when the dog tries hard to follow him that tied him, this root is easily plucked up, but the dog dies immediately, as it were, instead of the man that would take the plant away ".* Thus the dog takes the place of the dog-fish when the mandrake becomes the pearl's surrogate. The only discrepancy between the two stories is the point to which Josephus calls specific attention. For instead of the dog killing the thief, as the shark (dog fish) kills the stealer of pearls, the dog becomes the victim as a sub stitute for the man. As Josephus remarks, "the dog dies immediately, as it were, instead of the man that would take the plant away ". This distortion of the story is true to the traditions of legend-making. The dog-incident is so twisted as to be transformed into a device for plucking the dangerous plant without risk.

it is quite possible that earlier associations of the dog with the Great Mother may have played some part in this transference of meaning, if only by creating confusion which made such rationalization necessary. I refer to the part played by Anubis in helping Isis to collect the fragments of Osiris ; and the r óle played by Anubis, and his Greek avatar Cerberus, in the world of the dead. Whether the association of the dog-star Sirius with Hathor had anything to do with the confusion is uncertain.3

1 A number of versions of this widespread fable have been collected by Dr. Rendel Harris (pp. cit.) and Sir James Frazer (pp. cit.). I quote here from the former (p. 118).

2 Josephus, "Bell. Jud.,"VII, 6, 3, quoted by Rendel Harris, op. cit., p. 118.

3 The dog-star became associated with Hathor for reasons which are explained on p. 209. It was "the opener of the way "for the birth of the sun and the New Year.

There was an intimate association of the dog with the goddess of the underworld (Hecate) and the ritual of rebirth of the dead.1 Perhaps the development of the story of the underworld-goddess Aphrodite's dog and the mandrake may have been helped by this survival of the association of Isis with Anubis, even if there is not a more definite causal relationship between the dog-incidents in the various legends.

1 When Artemis acquired the reputation as a huntress and her deer be came her quarry the dog was rationalized into the new scheme.

The divine dog Anubis is frequently represented in connexion with the ritual of rebirth,2 where it is shown upon a standard in association with the placenta. The hieroglyphic sign for the Egyptian word mes, "to give birth,"consists of the skins of three dogs (or jackals, or foxes). The three-headed dog Cerberus that guarded the portal of Hades may possibly be a distorted survival of this ancient symbolism of the three-fold dog-skin as the graphic sign for the act of emergence from the portal of birth. Elsewhere (p. 223) in this lecture I have referred to Charon's obohts as a surrogate of the life-giving pearl or cowry placed in the mouth of the dead to provide "vital substance ". Rohde3 regards Charon as the second Cerberus, corresponding to the Egyptian dog-faced god Anubis: just as Charon received his obelus, so in Attic custom the dead were provided with the object of which is usually said to be to pacify the dog of hell.

2 See, for example, Morel's "Mystéres Égyptiens,"pp. 77-80 s "Psyche,"p. 244.

What seems to link all these fantastic beliefs and customs with the story of the dog and the mandrake is the fact that they are closely bound up with the conception of the dog as the guardian of hidden treasure.

The mandrake story may have arisen out of a mingling of these two streams of legend - the shark (dog-fish) protecting the treasures at the bottom of the sea, and the ancient Egyptian beliefs concerning the dog-headed god who presides at the embalmer's operations and superintends the process of rebirth.

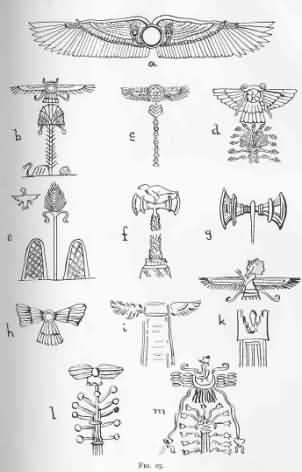

The dog of the story is a representative of the dragon guarding the goddess in the form of the mandrake, just as the lions over the gate at Mycenae heraldically support her pillar-form, or the serpents in Southern Arabia protect her as an incense tree. Dog, Lion, and

Serpent in these legends are all representatives of the goddess herself, i.e. merely her own avatars (Fig. 26).

At one time I imagined that the role of Anubis as a god of embalming and the restorer of the dead was merely an ingenuous device n the part of the early Egyptians to console themselves for the de predations of jackals in their cemeteries. For if the jackal were converted into a life-giving god it would be a comforting thought to believe that the dead man, even though devoured, was "in the bosom of his god "and thereby had attained a rebirth in the hereafter. In ancient Persia corpses were thrown out for the dogs to devour. There was also the custom of leading a dog to the bed of a dying man who presented him with food, just as Cerberus was given honey-cakes by Hercules in his journey to hell. But I have not been able to obtain any corroboration of this supposition. It is a remarkable coincidence that the Great Mother has been identified with the necrophilic vulture as Mut ; and it has been claimed by some writers1 that, just as the jackal was regarded as a symbol of rebirth in Egypt and the dead were exposed for dogs to devour in Persia, so the vulture's corpse-devouring habits may have been primarily responsible for suggesting its identification with the Great Mother and for the motive behind the Indian practice of leaving the corpses of the dead for the vultures to dispose of.2 It is not uncommon to find, even in English cathedrals, recumbent statues of bishops with dogs as footstools. Petronius ("Sat.,"c. 71) makes the following statement: "valde te rogo, ut secundum pedes statuae meae catellam pingas - ut mihi contingai tuo beneficio post mortem vivere ". The belief in the dog s service as a guide to the dead ranges from Western Europe to Peru.

1 See, for example, Jung, op. cit., p. 268.

3 Nekhebit, the Egyptian Vulture goddess, was identified by the Greeks with Eileithyia, the goddess of birth (Wiedemann, "Religion of the Ancient Egyptians,"p. 141). She was usually represented as a vulture hovering over the king. Her place can be taken by the falcon of Horus or in the Babylonian story of Etana by the eagle. In the Indian Mahabharata the Garuda is described as "the bird of liie . . . destroyer of all, creator of all".

To return to the story of the dog and the mandrake: no doubt the demand will be made for further evidence that the mandrake actually assumed the r óle of the pearl in these stories. If the remarkable repertory of magical properties assigned to the mandrake 1 to compared with those which developed in connexion with the cowry and the pearl,2 it will be found that the two series are identical. The mandrake also is the giver of life, of fertility to women, of safety in childbirth ; and like the cowry and the pearl it exerts these magical influences only if it be worn in contact with the wearer's skin.3 But the most definite indication of the mandrake's homology with the pearl is provided by the legend that "it shines by night ". Some scholars,4 both ancient and modern, have attempted to rationalize this tradition by interpreting it as a reference to the glow-worms that settle on the plant ! But it is only one of many attributes borrowed by the mandrake from the pearl, which was credited with this remarkable reputation only when early scientists conceived the hypothesis that the gem was a bit of moon substance.

As the memory of the real history of these beliefs grew dim, con fusion was rapidly introduced into the stories. I have already explained how the diving for pearls started the story of the great palace of treasures under the waters which was guarded by dragons. As the pearl had the reputation of shining by night, it is not surprising that it or some of its surrogates should in course of time come to be credited with the power of "revealing hidden treasures,"the treasures which in the original story were the pearls themselves. Thus the magic fern-seed and other treasure-disclosing vegetables 5 are surrogates of the mandrake, and like it derive their magical properties directly or indirectly from the pearl.

1 See Rendel Harris (pp. cii.} and Sir James Frazer (op. cit.).

2 Jackson, op. cit.

3 An interesting rationalization (of which Mr. T. H. Pear has kindly reminded me) of this ancient Oriental belief is still alive amongst British women. It is maintained that pearls " lose their lustre "unless they are worn in contact with the skin. This of course is a pure myth, but also an illuminating survival.

4 See Frazer, op. cit., p. 16, especially the references to the "devil's candle "and "the lamp of the elves ".

5 Rendel Harris, op. cit., p. 113: Other factors played a part in the development of this legend of opening up treasure-houses. Both Artemis and Hecate are associated with a magical plant capable of opening locks and helping the process of birth. Artemis is a goddess of the portal and her life-giving symbol in a multitude of varied forms is found appropriately placed above the lintel of doors.

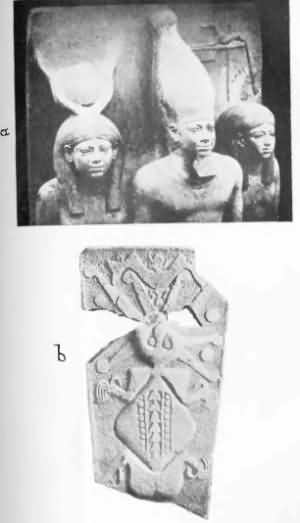

Fig. 21 (a)

Fig. 21 (a)

A SLATE TRIAD FOUND BY PROFESSOR G. A. REISNER IN THE TEMPLE

OF THE THIRD PYRAMID AT GlZA. If SHOWS THE PHAHAOH MYCKRINUS

SUPPORTED ON HIS RIGHT SIDE BY THE GODDESS HATHOR, REPRESENTED AS

A WOMAN WITH THE MOON AND THE COW'S HORNS UPON HER HEAD, AND ON

THE LEFT SIDE BY A NOME GODDESS, BEARING UPON HER HEAD THE

JACKAL-SYMBOL OF HER NOME.

(b) THE ECUADOR APHRODITE. BAS-RELIEF PROM CERRO JABONCILLO A

GROTESQUE COMPOSITE MONSTER 1NTKNDED TO REPRESENT A WOMAN WHOSE

HEAD IS A CONVENTIONALIZED OCTOPUS. WHOSE BODY IS A LOLIGO, AND

WHOSE LIMBS ARE HUMAN.

The fantastic story of the dog and the mandrake provides the most definite evidence of the derivation of the mandrake-beliefs from the shell-cults of the Erythraean Sea. There are many other scraps of evidence to corroborate this. I shall refer here only to one of these. "The discovery of the art of purple-dyeing has been attributed to the Tyrian tutelary deity Melkart, who is identified with Baal by many writers. According to Julius Pollux (' Onomasticon/ I, iv.) and Nonnus (' Dionys.,' XL, 306) Hercules (Melkart) was walking on the seashore accompanied by his dog and a Tyrian nymph, of whom he was enamoured. The dog having found a Murex with its head protruding from its shell, devoured it, and thus its mouth became stained with purple. The nymph, on seeing the beautiful colour, bargained with Hercules to provide her with a robe of like splendour."This seems to be another variant of the same story.

THE OCTOPUS

Aphrodite was associated not only with the cowry, the pearl, and the mandrake, but also with the octopus, the argonaut, and other céphalopode. Tumpel seems to imagine that the identification of the goddess with the argonaut and the octopus necessarily excludes her association with molluscs ; and Dr. Rendel Harris attributes an equally exclusive importance to the mandrake. But in such methods of argument due recognition is not given to the outstanding fact in the history of primitive beliefs. The early philosophers built up their great generalizations in the same way as their modern successors. They were searching for some explanation of, or a working hypothesis to include, most diverse natural phenomena within a concise scheme. The very essence of such attempts was the institution of a series of homologies and fancied analogies between dissimilar objects. Aphrodite was at one and the same time the personification of the cowry, the conch shell, the purple shell, the pearl, the lotus, and the lily, the mandrake and the bryony, the incense tree and the cedar, the octopus and the argonaut, the pig, and the cow.

Every one of these identifications is the result of a long and chequered history, in which fancied resemblances and confusion of meaning play a very large part. But I cannot too strongly repudiate the claim made by Sir James Frazer that such events are merely so many evidences of the innate human tendency to personify nature The history of the arbitrary circumstances that were responsible for the development of each one of these homologies is entirely fatal to this wholly unwarranted speculation.1 Tumpel claims2 the Aphrodite was associated more especially with "a species of Sepia ". He refers to the attempts to associate the goddess of love with amulets of univalvular shells "in virtue of a certain peculiar and obscene symbol ism ", Naturalists, however, designate with the term Venus Cytherca certain gaping bivalve molluscs.

But, according to Tumpel (p. 386), neither univalvular nor bivalve shells can be regarded as a real part of the goddess's cultural equip ment. There is no representation of Aphrodite coming in a shell from across the sea.3 The truly sacred Aphrodite-shell was entirely different, so Tumpel believes : it was obviously difficult to preserve, but for that reason more worthy of notice, for the small pectines, virginalia marina (Apuleius de mag. 34, 35, and in reference thereto, Isidor. origg. 9, 5, 24) or spuria were only the commoner and more readily obtained surrogates: the univalvular shells such as those just mentioned, and the other the Nerites (periwinkles, etc.), the purple shell and the Echineis were also real Veneriae conchae. Among the Nerites Aelian enumerates. On account of their supposed medicinal value in cases of abortion and especially as a prophylactic for pregnant women the 'Evtvriic (pure Latin re[mi]mora) was called pisciculus !. According to Mutianus (Pliny, 9, 25 (41), 79 f.), it was a species of purple shell, but larger than the true Murex purpura. From this the sanctity of the Echine'is to the Cnidian Aphrodite is demonstrated: "quibus (conchis) inhaerentibus plenam venris stetisse navem portantem Periandro, ut castrarentur nobilis pueros, conchasque, quae id praestiterint, apud Cnidiorum Venerem coli"

1 Sir James Frazer, "Jacob and the Mandrakes," Proc. Brit. Academy.

2 K. Tumpel, "Die ' Muschel der Aphrodite,' " Phaologus, Zeitschrift fur das Classische Altenhum, Bd. 51, 1892, p. 385: compare also, with reference to the "Muschel der Aphrodite,"O. Jahn, SB. d. k. Sacks G. d. W., VII, 1853, p. 16 ff. ; also IX, 1855, p. 80 ; and Stephani, Compte rendu pour l'an 1870-71, p. 17 ff.

3 The fact that no graphic representation of this event has been found is surely a wholly inadequate reason for refusing to credit the story. Very few episodes in the sacred history of the gods received concrete expression in pictures or sculptures until relatively late. A Hellenistic representation of the goddess emerging from a bivalve was found in Southern Russia (Minns, "Scythians and Greeks,"p. 345).

Tumpel cites the following statements: "te (Venus) ex concha natam esse autumant: cave tu harum conchas spernas ! "Tibull. 3, 3, 24: "et fa veas concha, Cypria, vecta tua"; Statius Silv. 1, 2, 117: Venus to Violentilla, "haec et caeruleis mecum consurgere digna fluctibus et nostra potuit considere concha "; Fulgent, myth. 2, 4 "concha etiam marina pingitur (Venus) portari (I. HS: - am portare) "; Paulus Diacon. p. 52, "M. Cytherea Venus ab urbe Cythera, in quam primum devecta esse dicitur concha, cum in man esset concepta cet ".

Tumpel then (p. 387) accuses Stephani of being mistaken in his interpretation of Martial's Cytheriacae (Epign. II, 47, 1 = purple shells) as the amulets of Aphrodite, and claims that Jahn has given the correct solution of the following passages from Pliny (N.H., 9, 33 [52], 103, compare 32, 1 1 [53])"navigant ex his (conchis) veneriae, praebentesque concavam sui partem et aurae opponentes per summa aequorum velificant "; and further (9, 30 [49], 94): "in Propontide conchara esse acatii modo carinatam inflexa puppe, prora rostrata, in hac condi nauplium animal saepiae simile ludendi societate sola, duobus hoc fieri generibus: tranquillum enim vectorem demissis palmulis ferire ut remis ; si vero flatus invitet, easdem in usu gubemaculi porrigi pandique buccarum sinus aurae ".

Tumpel claims (pp. 387 and 388) that this quotation settles the question. Aphrodite's "shell,"according to him, is the Nauphus (depicted as a shell-fish, with its sail-like palmulae spread out to the wind, but with the same sails flattened into plate-like arms for steering), clearly "a species of Sepia" wholly like Aphrodite herself, a ship- like shell-fish sailing over the surface of the water, the concha veneria. [The analogy to a ship bearing the Great Mother is extremely ancient and originally referred to the crescent moon carrying the moon-goddess across the heavenly ocean.]

Elsewhere (p. 399) he discusses the reasons for the connexion of Aphrodite with the "nautilus,"by which is meant the argonaut of zoologists.

But if Jahn and Tumpel have thus clearly established the proof of the intimate association of Aphrodite with certain céphalopode, they are wholly unjustified in the assumption that their quotations from relatively modern authors disprove the reality of the equally close (though more ancient) relationship of the goddess to the cowry, the pearl-shell, the trumpet-shell, and the purple-shell.

It must not be forgotten that, as we have already seen, the primitive shell-cults of the Erythraean Sea had been diffused throughout the Mediterranean area long before Aphrodite was born upon the shores of the Levant, and possibly before Hathor came into existence in the south. The use of the cowry and gold models of the cowry goes back to an early time in AEgean history.1 And the influence of Aphrodite's early associations had become blurred and confused by the development of new links with other shells and their surrogates. 2

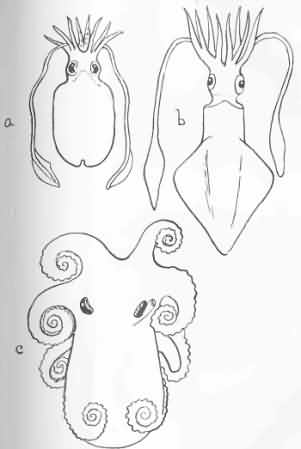

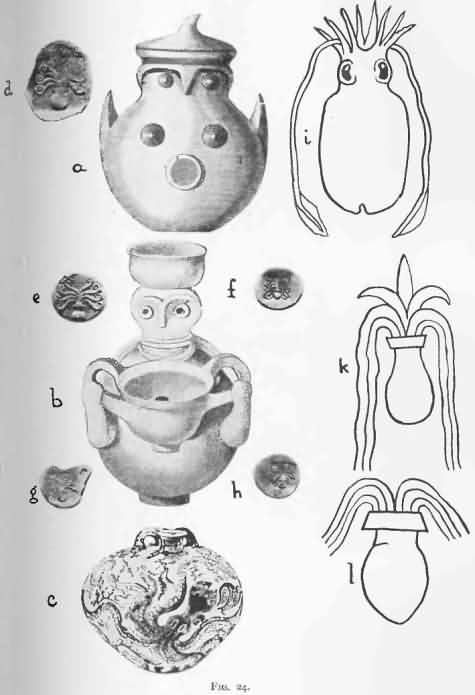

Fig.22. (a) Sepia Officinalis, after Tryon, "Cephalopoda"

(b) Loligo Vulgaris, after Tryon.

(c) The position usually adopted by the resting octopus, after Tryon.

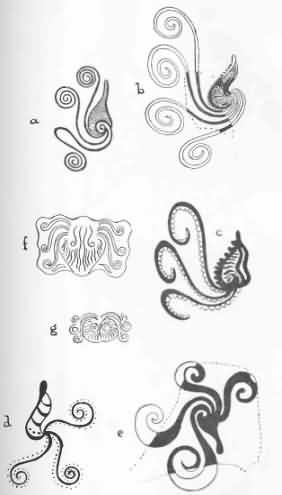

But the connexion of Aphrodite with the octopus and its kindred played a very obtrusive part in Minoan and Mycenaean art ; and its influence was spread abroad as far as Western Europe " and towards the East as far as America. In many ways it was a factor in the development of such artistic designs as the spiral and the volute, and not improbably also of the swastika.

Starting from the researches of Tumpel, a distinguished French zoologist, Dr. Frederic Houssay,3 sought to demonstrate that the cult of Aphrodite was "based upon a pre-existing zoological philosophy ". The argument in support of his claim that Aphrodite was a personification of the octopus must be sharply differentiated into two parts: first, the reality of the association of the octopus with the goddess, of which there can be no doubt ; and secondly, his explanation of it, which (however popular it may be with classical writers and modern scholars) 4 is not only a gratuitous assumption, but also, even if it were based upon more valid evidence than the speculations of such recent writers as Pliny, would not really carry the explanation very far.

1 See Schliemann, "ilios,"p. 455 ; and Siret, op. cit.

2 Siret, op. cit. supra, p. 59.

3 "Les Théories de la Genése a Mycénes et le sens zoologique de certains symboles du culte d'Aphrodite,"Revue Archéologique, 3!e série, T. XXVI, 1895, p. 13.

4 It was adduced also by Tumpel and others before him.

I refer to Kis claim that "les premiers conquérants de la mer furent induits en vénération du poulpe nageur (octopus) parce qu'ils crurent nue quelque-uns de ces céphalopodes, les poulpes sacrés (argonauta) avaient, comme eux et avant eux, inventé la navigation " (pp. cit., p. 15). Idle fancies of this sort do not help us to understand the arbi trary beliefs concerning the magical powers of the octopus.

The real problem we have to solve is to discover why, among all the multitude of bizarre creatures to be found in the Mediterranean Sea, the octopus and its allies should thus have been singled out for distinctive appreciation, and also acquired the same remarkable attri butes as the cowry.

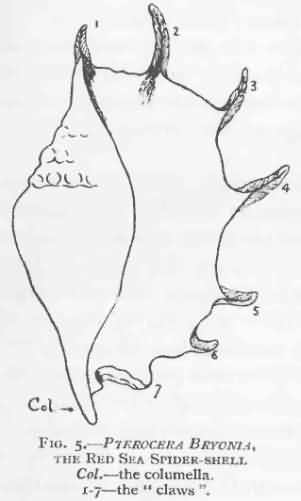

I believe that the Red Sea "Spider shell,"Pterocera, was the link between the cowry and the octopus. This shell was used, like the cowry, for funeraiy purposes in Egypt and as a trumpet in India. But it was also depicted upon a series of remarkable primitive statues of the god Min, which were found at Coptos during the winter 1893-4 by Professor Flinders Pétrie. Some of these objects are now in the Cairo Museum and the others in the Ashmolean Museum in Ox ford. They are supposed to be late predynastic representations of the god Min. If this supposition is correct they are the earliest idols (apart from mere amulets) that have been preserved from antiquity.

Upon these statues, representations of the Red Sea shell Pterocera bryonia are sculptured in low relief. Mr. F. LI. Griffith is disinclined to accept my suggestion that the object of these pictures of the shell was to animate the statues. But whether this was their purpose or not, it is probably not without some significance that these life-giving shells were associated with so obtrusively phallic a deity as Min. In any case they afford concrete evidence of cultural contact between Coptos and the Red Sea, and indicate that these particular shells were chosen as symbols of that sea or its coast.

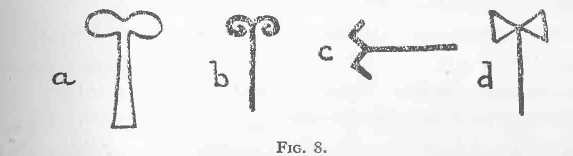

The distinctive feature of the Pterocera is that the mantle in the adult expands into a series of long finger-like processes each of which secretes a calcareous process or "claw ". There are seven of these claws as well as the long columella (Fig. 5). Hence, when the shell-cults were diffused from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean (where the Pterocera is not found), it is quite likely that the people of the Levant may have confused with the octopus some sailor's account of the eight-rayed shell (or perhaps representations of it on some amulet or statue). Whether this is the explanation of the confusion or not, it is certain that the beliefs associated with the cowry and the octopus in the AEgean area are identical with those linked up with the cowry and the Pterocera in the Red Sea.

I have already mentioned that the mandrake is believed to possess the same magical powers. Sir James Frazer has called attention to the fact that in Armenia the bryony (Bryonia alba) is a surrogate of the mandrake and is credited with the same attributes. Lovell Reeve ("Conchologia Iconica,"VI, 1851) refers to the Red Sea Pterocera as the "Wild Vine Root " species, previously known as Strombus radix bryoniae ; and Chemnitz ("Conch. Cab.,"1788, Vol. X, p. 227) says the French call it "Racine de brione femelle imparfaite,"and refer to it as "the maiden ". Here then is further evidence that this shell (a) was associated in some way with a suiTogate of the mandrake (Aphrodite), and (b] was re garded as a maiden. T hus clearly it has a place in the chequered history of Aphrodite. I have suggested the possibility of its con fusion with the octopus, which may have led to the inclusion of the latter within the scope of the marine creatures in Aphrodite s cultural equipment. According to Matthioli (Lib. 2, p. 135), another of Aphrodite's creatures, the purple shell-fish, was also known as "the maiden ". By Pliny it is called Pelogia, in Greek was the term applied to the flesh of swine that had been sacrificed to Ceres and Proserpine (Hesych.). In fact, the purple-shell was "the maiden "and also "the sow ": In other words it was Aphrodite. The use of the term "maiden "for the Pterocera suggests a similar identification. To complete this web of proof it may be noted that an old writer has called the mandrake the plant of Circe, the sorceress who turned men into swine by a magic draught.1 Thus we have a series of shells, plants, and marine creatures accredited with identical magical properties, and each of them known in popular tradition as "the maiden ". They are all culturally associated with Aphrodite.

1 Just as Hathor (or her surrogate Horus) turned men into the creatures of Set, i.e. pigs, crocodiles, et cetera.

I shall have occasion to refer to M. Siret's account of the discovery of the AEgean octopus-motif upon AEneolithic objects in Spain, and of the widespread use in Western Europe of certain conventional designs derived from the octopus. M. Siret also (see the table, Fig. 6, on p. 34 of his book) makes the remarkable claim that the conventional form of the Egyptian Bes, which, according to Quibell,2 is the god whose function it is to preside over sexual intercourse in its purely physical aspect, is derived from the octopus. If this is true - and I am bound to admit that it is far from being proved - it suggests that the Red Sea littoral may have been the place of origin of the cultural use of the octopus and an association with Hathor, for Bes and Hathor are said to have been introduced into Egypt from there.

That the octopus was actually identified with the Great Mother and also with the dragon is revealed by the fact of the latter assuming an octopus-form in Eastern Asia and Oceania, and by the occurrence of octopus-motifs in the representation of the goddess in America. One of the most remarkable series of pictures depicting the Great Mother is found sculptured in low relief upon a number of stone slabs from Manabi in Central America, one of which I reproduce here.

The head of the goddess is a conventionalised octopus; to that was added a body consisting of a Loligo ; and, to give greater definiteness to this remarkable process of building up the form of the goddess, conventional representations of her arms and legs (and in some of the sculptures also the pudetidum muliebré) were added. Thus there can be no doubt of the identification of this American Aphrodite and the octopus.

In the Polynesian Rata-myth there is a very instructive series of manifestations of the dragon.1 The first form assumed by the monster in this story was a gaping shell-fish of enormous size ; then it appeared as a mighty octopus ; and lastly, as a whale, into whose jaws the hero Nganaoa sprang, as his representatives are said to have done elsewhere throughout the world (Frobenius, op. cit., pp. 59-219).

Houssay (pp. cit. infra) calls attention to the fact that at times Astarte was shown carrying an octopus as her emblem/ and has sugested that it was mistaken for a hand, just as in America the thunder bolt of Chac was given a hand-like form in the Dresden Codex (vide supra, Fig. 13), and elsewhere (e.g. Fig. 12).