The Evolution Of The Dragon By G. Elliot Smith

M.A., M.D., F.R.S.

CHAPTER II. DRAGONS AND RAIN GODS.*

1919

* An elaboration of a Lecture delivered in the John Rylands Library on 8 November, 1916.

AN adequate account of the development of the dragon-legend would represent the history of the expression of mankind's aspirations and fears during the past fifty centuries and more For the dragon was evolved along with civilization itself. The search for the elixir of life, to turn back the years from old age and confer the boon of immortality, has- been the great driving force that compelled men to build up the material and the intellectual fabric of civilization. The dragon-legend is the history of that search which has been pre served by popular tradition : it has grown up and kept pace with the constant struggle to grasp the unattainable goal of men's desires; and the story has been constantly growing in complexity, as new incidents were drawn within its scope and confused with old incidents whose real meaning was forgotten or distorted. It has passed through all the phases with which the study of the spreading of rumours or the development of dreams has familiarized students of psychology. The simple original stones, which become blended and confused, their meaning distorted and reinterpreted by the rationalizing of incoherent incidents, are given the dramatic form with which the human mind invests all stories that make a strong appeal to its emotions, and then secondarily elaborated with a wealth of circumstantial detail. This is the history of popular legends and the development of rumours. But these phenomena are displayed in their most emphatic form in dreams.2 In his waking state man restrains his roving fancies and exercises what Freud has called a " censorship " over the stream of his thoughts : but when he falls asleep, the " censor" dozes also; and free rein is given to his unrestrained fancies to make a hotch-potch of the most varied and unrelated incidents, and to create a fantastic mosaic built up from fragments of his actual experience, bound together by the cement of his aspirations and fears. The myth resembles the dream because it has developed without any consistent and effective censorship. The individual who tells one particular phase of the story may exert the controlling influence of his mind over the version he narrates : but as it is handed on from man to man and generation to generation the " censorship " also is constantly changing. This lack of unity of control implies that the development of the myth is not unlike the building-up of a dream-story.

l In his lecture, " Dreams and Primitive Culture," delivered at the John Rylands Library on 10 April, 1918, Dr. Rivers has expounded the principles of dream-development.

But the dragon-myth is vastly more complex than any dream, because mankind as a whole has taken a hand in the process of shaping it; and the number of centuries devoted to this work of elaboration has been far greater than the years spent by the average individual in accumulating the stuff of which most of his dreams have been made. But though the myth is enormously complex, so vast a mass of detailed evidence concerning every phase and every detail of its history has been preserved, both in the literature and the folk-lore of the world, that we are able to submit it to psychological analysis and determine the course of its development and the significance of every incident in its tortuous rambling.

In instituting these comparisons between the development of myths and dreams, I should like to emphasize the fact that the interpretation of the myth proposed in these pages is almost diametrically opposed to that suggested by Freud, and pushed to a reductio ad absurdum by his more reckless followers, and especially by Yung.

The dragon has been described as " the most venerable symbol employed in ornamental art and the favourite and most highly decorative motif in artistic design ". It has been the inspiration of much, if not most, of the world's great literature in every age and clime, and the nucleus around which a wealth of ethical symbolism has accumulated throughout the ages. The dragon-myth represents also the earliest doctrine or systematic theory of astronomy and meteorology.

In the course of its romantic and chequered history the dragon has been identified with all of the gods and all of the demons of every religion. But it is most intimately associated with the earliest stratum of divinities, for it has been homologized with each of the members of the earliest Trinity, the Great Mother, the Water God, and the Warrior Sun God, both individually and collectively. To add to the complexities of the story, the dragon-slayer is also represented by the same deities, either individually or collectively; and the weapon with which the hero slays the dragon is also homologous both with him and his victim, for it is animated by him who wields it, and its powers of destruction make it a symbol of the same power of evil which it itself destroys.

Such a fantastic paradox of contradictions has supplied the materials with which the fancies of men of every race and land, and every stage of knowledge and ignorance, have been playing for all these centuries It is not surprising, therefore, that an endless series of variations of the story has been evolved, each decked out with topical allusions and distinctive embellishments. But throughout the complex tissue of this highly embroidered fabric the essential threads of the web and wool of its foundation can be detected with surprising constancy and regularity.

Within the limits of such an account as this it is obvious that I can deal only with the main threads of the argument and leave the interesting details of the local embellishments until some other time.

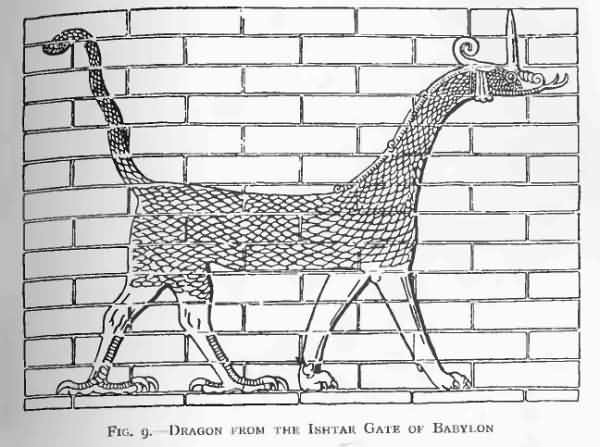

The fundamental element in the dragon's powers is the control of water. Both in its beneficent and destructive aspects water was regarded as animated by the dragon, who thus assumed the role of Osiris or his enemy Set. But when the attributes of the Water God became confused with those of the Great Mother, and her evil avatar, the lioness (Sekhet) form of Hathor in Egypt, or in Babylonia the destructive Tiamat, became the symbol of disorder and chaos, the dragon became identified with her also.

Similarly the third member of the Earliest Trinity also became the dragon. As the son and successor of the dead king Osiris the living king Horus became assimilated with him. When the belief became more and more insistent that the dead king had acquired the boon of immortality and was really alive, the distinction between him and the actually living king Horus became correspondingly minimized. This process of assimilation was advanced a further stage when the king became a god and was thus more closely identified with his father and predecessor. Hence Horus assumed many of the functions of Osiris; and amongst them those which in foreign lands contributed to making a dragon of the Water God. But if the distinction between Horus and Osiris became more and more attenuated with the lapse of time, the identification with his mother Hathor (Isis) was more later still. For he took her place and assumed many of her attributes in the later versions of the great saga which is the nucleus of all literature of mythology - I refer to the story of " The Destruction Of Mankind ".

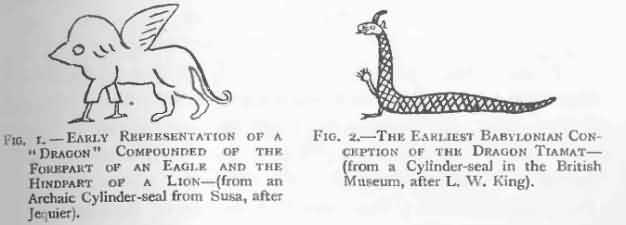

The attributes of these three members of the Trinity, Hathor, Osiris and Horus, thus became intimately linked the one with the other and in Susa, where the earliest pictorial representation of a real dragon developed, it received concrete form (Fig. 1 ) as a monster compounded of the lioness of Hathor (Sekhet) with the falcon (or eagle) of Horus, but with the human attributes and water-controlling powers which originally belonged to Osiris. In some parts of Africa the earliest " dragon " was nothing more than Hathor's cow or the gazelle or antelope of Horus (Osiris) or of Set.

But if the dragon was compounded of all three deities, who was the slayer of the evil dragon?

The story of the dragon-conflict is really a recital of Horus's vendetta against Set, intimately blended and confused with different versions of " The Destruction of Mankind ' The commonplace incidents of the originally prosaic stories were distorted into an almost unrecognizable form, then secondarily elaborated without any attention to their original meaning, but with a wealth of circumstantial embellishment, in accordance with the usual methods of the human mind that I have already mentioned. The history of the legend is in fact the most complete, because it is the oldest and the most widespread, illustration of those instinctive tendencies of the human spirit to bridge the gaps in its disjointed experience, and to link together in a kind Of mental mosaic the otherwise isolated incidents in the facts of daily life and the rumours and traditions that have been handed down from the story-teller's predecessors.

In the " Destruction of Mankind," which I shall discuss more fully in the following pages, Hathor does the slaying; in the later stories Horus takes his mother's place and earns his spurs as the Warrior Sun-god :1 hence confusion was inevitably introduced between the enemies of Re, the original victims in the legend, and Horus's traditional enemies, the followers of Set. Against the latter it was Osiris himself who fought originally; and in many of the non-Egyptian variants of the legend it is the rain-god himself who is the warrior.

1 Hence soldiers killed in battle and women dying in childbirth receive special consideration in the exclusive heaven of (Osiris's) Horus's Indian and American representatives, Indra and Tlaloc.

Hence all three members of the Trinity were identified, not only with the dragon, but also with the hero who was the dragon-siayer.

But the weapon used by the latter was also animated by the same Trinity, and in fact identified with them. In the Saga of the Winged Disk, Horus assumed the form of the sun equipped with the wings of his own falcon and the fire-spitting uraeus serpents. Flying down from heaven in this form he was at the same time the god and the god's weapon. As a fiery bolt from heaven he slew the enemies of Re, who were now identified with his own personal foes, the followers of Set. But in the earlier versions of the myth (i.e. the " Destruction of Man kind "), it was Hathor who was the " Eye of Re " and descended from heaven to destroy mankind with fire; she also was the vulture (Mut); and in the earliest version she did the slaughter with a knife or an axe with which she was animistically identified.

But Osiris also was the weapon of destruction, both in the form of the flood (for he was the personification of the river) and the rain-storms from heaven. But he was also an instrument for vanquishing the demon, when the intoxicating beer or the sedative drink (the potency of which was due to the indwelling spirit of the god) was the chosen means of overcoming the dragon.

This, in brief, is the framework of the dragon-story. The early Trinity as the hero, armed with the Trinity as weapon, slays the dragon, which again is the same Trinity. With its illimitable possibilities for dramatic development and fantastic embellishment with incident and ethical symbolism, this theme has provided countless thousands of story-tellers with the skeleton which they clothed with the living flesh of their stories, representing not merely the earliest theories of as astronomy and meteorology, but all the emotional conflicts of daily life, the struggle between light and darkness, heat and cold, right and wrong, justice and injustice, prosperity and adversity, wealth and poverty. The whole gamut of human strivings and emotions was drawn into the legend until it became the great epic of the human spirit and the main theme that has appealed to the interest of all mankind in every age.

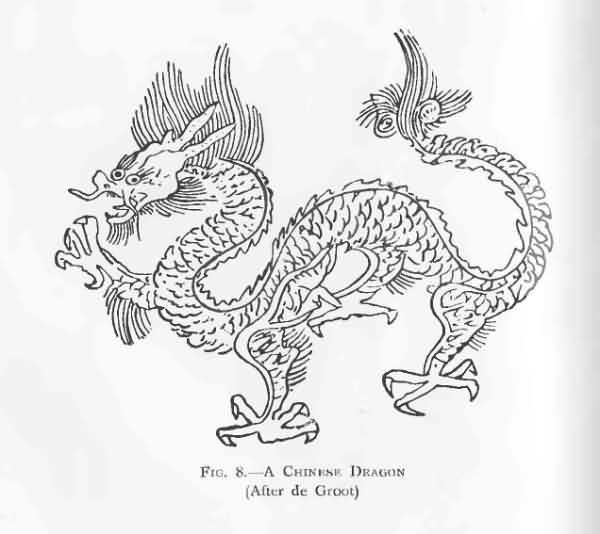

An ancient Chinese philosopher, Wang Fu, writing in the time of the Han Dynasty, enumerates the " nine resemblances " of the dragon. " His horns resemble those of a stag, his head that of a camel, his eyes those of a demon, his neck that of a snake, his belly that of a clam, his scales those of a carp, his claws those of an eagle, his soles those of a tiger, his ears those of a cow."1 But this list includes only a small minority of the menagerie of diverse creatures which at one time or another have contributed their quota to this truly astounding hotch potch.

1 M. W. de Visser, " The Dragon in China and Japan," Verhandelin gen der Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam, Afdeeling Letterkunde, Deel X11I, No. 2, 1913, p. 70.

This composite wonder-beast ranges from Western Europe to the Far East of Asia, and as we shall see, also even across the Pacific to America. Although in the different localities a great number of most varied ingredients enter into its composition, in most places where the dragon occurs the substratum of its anatomy consists of a serpent or a crocodile, usually with the scales of a fish for covering, and the feet and wings, and sometimes also the head, of an eagle, falcon, or hawk, and the fore limbs and sometimes the head of a lion. An association of anatomical features of so unnatural and arbitrary a nature can only mean that all dragons are the progeny of the same ultimate ancestors.

But it is not merely a case of structural or anatomical similarity, hut also of physiological identity, that clinches the proof of the derivation of this fantastic brood from the same parents. Wherever the dragon is found, it displays a special partiality for water. It controls the rivers or seas, dwells in pools or wells, or in the clouds on the tops of mountains, regulates the tides, the flow of streams, or the rainfall and is associated with thunder and lightning. Its home is a manse at the bottom of the sea, where it guards vast treasures, usually pearl but also gold and precious stones. In other instances the dwelling j upon the top of a high mountain; and the dragon's breath form the rain-clouds. It emits thunder and lightning. Eating the dragon's heart enables the diner to acquire the knowledge stored in this " organ of the mind " so that he can understand the language of birds, and in fact of all the creatures that have contributed to the making Of , dragon.

It should not be necessary to rebut the numerous attempts that have been made to explain the dragon-myth as a story relating to extinct monsters. Such fantastic claims can be made only by writers devoid of any knowledge of palaeontology or of the distinctive features of the dragon and its history. But when the Keeper of the Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities in the British Museum, in a book that is not intended to be humorous,1 seriously claims Dr. Andrews' discovery of a gigantic fossil snake as " proof " of the former existence of " the great serpent-devil Apep," it is time to protest.

1 E. A. Wallis Budge, "The Gods of the Egyptians," 1904, vol. i

Those who attempt to derive the dragon from such living creatures as lizards like Draco volans or Moloch horridus2 ignore the evidence of the composite and unnatural features of the monsters.

2Gould's "Mythical Monsters," 1886.

"Whatever be the origin of the Northern dragon, the myths, when they first became articulate for us, show him to be in all essentials the same as that of the South and East. He is a power of evil, guardian of hoards, the greedy withholder of good things from men; and the slaying of a dragon is the crowning achievement of heroes - of Siegmund, of Beowulf, of Sigurd, of Arthur, of Tristam - even of Lancelot, the beau ideal of mediaeval chivalry " (Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. viii., p. 467). But if in the West the dragon is usually a "power of evil," in the far East he is equally emphatically a symbol of beneficence. He is identified with emperors and kings; he is the son of heaven the bestower of all bounties, not merely to mankind directly, but also to the earth as well.

Even in our country his symbolism is not always wholly malevolent, otherwise - if for the moment we shut our eyes to the history of the development of heraldic ornament - dragons would hardly figure as the supporters of the arms of the City of London, and as the symbol of many of our aristocratic families, among which the Royal House of Tudor is included. It is only a few years since the Red Dragon of Cadwallader was added as an additional badge to the achievement of the Prince of Wales. But, "though a common ensign in war, both and the West, as an ecclesiastical emblem his opposite qualities have remained consistently until the present day. Whenever the dragon is represented, it symbolizes the power of evil, the devil and his works. Hell in mediaeval art is a dragon with gaping jaws, belching fire".

And in the East the dragon's reputation is not always blameless. For it figures in some disreputable incidents and does not escape the sort of punishment that tradition metes out to his European cousins.

THE DRAGON IN AMERICA AND EASTERN ASIA.

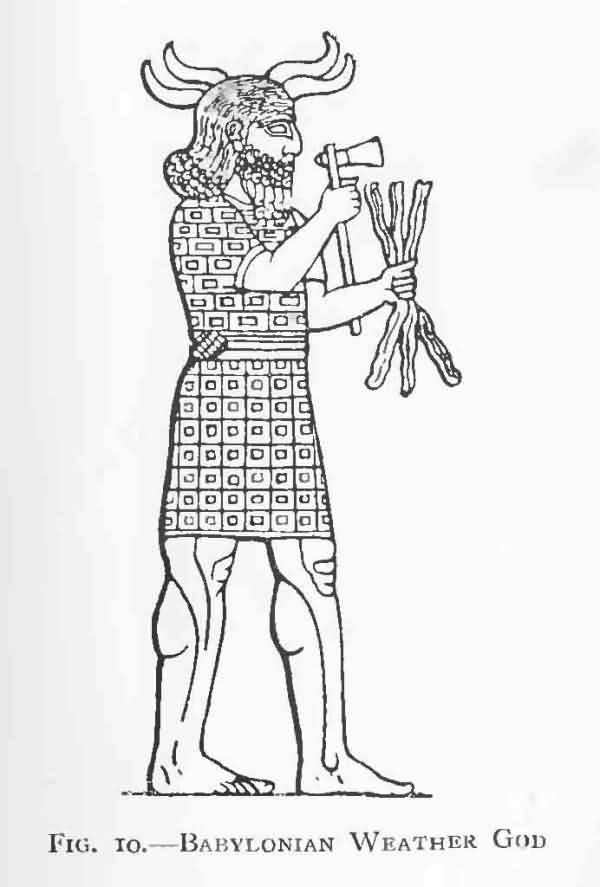

In the early centuries of the Christian era, and probably also even for two or three hundred years earlier still, the leaven of the ancient civilizations of the Old World was at work in Mexico, Central America and Peru. The most obtrusive influences that were brought to bear, especially in the area from Yucatan to Mexico, were inspired by the Cambodian and Indonesian modifications of Indian beliefs and practices. The god who was most often depicted upon the ancient Maya and Aztec codices was the Indian rain-god Indra, who in America was provided with the head of the Indian elephant, (i.e. seems to have been confused with the Indian Ganesa) and given other attributes more suggestive of the Dravidian Nâga than his enemy, the Aryan deity. In other words the character of the American god, known as Ckac by the Maya people and as Tlaloc by the Aztecs, is an interesting illustration of the effects of such a mixture of cultures as Dr. Rivers has studied in Melanesia.1

1 '"History of Melanesian Society," Cambridge, 1914.

Not only does the elephant-headed god in America represent a blend of the two great Indian rain-gods which in the Old World are mortal enemies,' the one of the other (partly for the political reason that the Dravidians and Aryans were rival and hostile peoples), but all the traits of each deity, even those depicting the old Aryan conception of their deadly combat, are reproduced in America under circumstances which reveal an ignorance on the par[ of the artists of the significance of the paradoxical contradictions they are representing. But even many incidents in the early history of the Vedic gods, which were due to arbitrary circumstances in the growth of the legends, reappear in America. To cite one instance (out of scores which might be quoted), in the Vedic story Indra assumed many of the attributes of the god Soma. In America the name of the god of rain and thunder, the Mexican Indra, is Tlaloc, which is generally translated "plaque of the earth," from the "earth," and pulque[" pulque, a fermented drink (like the Indian drink soma) made from the juice of the agave ".l

The so-called " long-nosed god " (the elephant-headed rain-god) has been given the non-committal designation " god B," by Schellhas.;

1 H. Beuchat, "Manuel d' Archéologie

Américaine," 1912, p. 319.

'2 " Representation of Deities of the Maya Manuscripts," Papers

of th Peabody Museum, vol. iv., 1904.

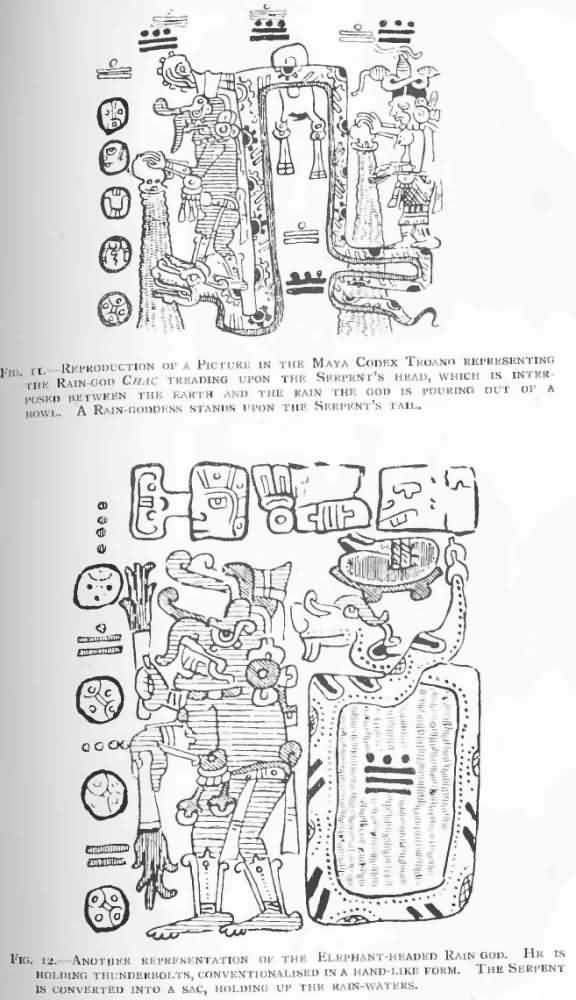

I reproduce here a remarkable drawing (Fig. 11 ) from the Codex Troano, in which this god, whom the Maya people called Choc, is shown pouring the rain out of a water-jar (just as the deities of Babylonia and India are often represented), and putting his foot upon the head of a serpent, who is preventing the rain from reaching the earth. Here we find depicted with childlike simplicity and directness the Vedic conception of Indra overcoming the demon Vritra. Stempell describes this scene as " the elephant-headed god standing upon the head of a serpent "; while Seler, who claims that god is a tortoise, explains it as the serpent forming a footstool for the rain-god.3 In the Codex Cortes the same theme is depicted in another way, which is truer to the Indian conception of Vritra, as " the restrainer "T (Fig. 12).

4 " Die Tierbilder der mexikanischen und der Maya-Handschriften," Zeitschrift Ethnologie, Bd. 42, 1910, pp. 75 and 77. In the remark able series of drawings from Maya and Aztec sources reproduced by Seler in his articles in the Zeitschrift Ethnologie, the Peabody Museum Papers, and his monograph on the Codex Vaticanus, not only is practically every episode of the dragon-myth of the Old World graphically depicted, but also every phase and incident of the legends from India (and Babylonia, Egypt and the AEgean) that contributed to the building-up of the myth.

The serpent (the American rattlesnake) restrains the water by coiling itself into a sac to hold up the rain and so prevent it from reaching the earth. In the various American codices this episode is depicted in as great a variety of forms as the Vedic poets of India described when they sang of the exploits of Indra. The Maya Chac is, in fact, Indra transferred to the other side of the Pacific and there only thinly disguised by a veneer of American stylistic design.

But the Aztec god Tlaloc is merely the Chac of the Maya people transferred to Mexico. Schellhas declares that the " god B," the " most common figure in the codices," is a " universal deity to whom the most varied elements, natural phenomena, and activities are subject " Many authorities consider God B to represent Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent, whose Aztec equivalent is Quetzalcoatl. Others identify him with Itzamna, the Serpent God of the East, or with Chac, the Rain God of the four quarters and the equivalent of Tlaloc of the Mexicans." 2

1 Compare Hopkins, " Religions of India," p. 94.

2 Herbert J. Spinden, " Maya Art," p. 62.

From the point of view of its Indian analogies these confusions are peculiarly significant, for the same phenomena are found in India. The snake and the dragon can be either the rain-god of the East or the enemy of the rain-god; either the dragon-slayer or the evil dragon who has to be slain. The Indian word Naga, which is applied to the beneficent god or king identified with the cobra, can also mean "elephant," and this double significance probably played a part in the confusion of the deities in America.

In the Dresden Codex the elephant-headed god is represented in one place grasping a serpent, in another issuing from a serpent's mouth, and again as an actual serpent (Fig. 13). Turning next to the attributes of these American gods we find that they reproduce with amazing precision those of Indra. Not only were they the divinities who controlled rain, thunder, lightning, and vegetation, but they also earned axes and thunderbolts (Fig. 13) like their homologues in the Old World. Like Indra, Tlaloc was intimately associated with the East and with the tops of mountains, where he had a special heaven, reserved for warriors who fell in battle and women who died in childbirth. As a water-god also he presided over the souls of the drowned and those who suffered from dropsical affections. Indra also specialized in the same branch of medicine.

In fact, if one compares the account of Tlaloc's attributes and achievements, such as is given in Mr. Joyce's " Mexican Archaeology" or Professor Seler's monograph on the "Codex Vaticanus," with Professor Hopkins's summary of Indra's character (" Religions of India ") the identity is so exact, even in the most arbitrary traits and confusions with other deities' peculiarities, that it becomes impossible for any serious investigator to refuse to admit that Tlaloc and Chac are merely American forms of Indra. Even so fantastic a practice as the representation of the American rain-god's face as composed of contorted snakes1 finds its analogy in Siam, where in relatively recent times this curious device was still being used by artists.2

1 Seler, " Codex Vaticanus," Figs. 299-304.

2 See, for example, F. W. K. Müller, " Nang," Int. Arch.f. Ethnolog., 1894, Suppl. zu Bd. vii., Taf. vii., where the mask of Ravana (a late surrogate of Indra in the Ramayana) reveals a survival of the prototype of the Mexican designs.

" As the god of fertility maize belonged to him [Tlaloc], though not altogether by right, for according to one legend he stole it after it had been discovered by other gods concealed in the heart of a mountain."3 Indra also obtained soma from the mountain by similar means.4

3 Joyce, op. cit., p. 37.

4 For the incident of the stealing of the soma by Garuda, who in this legend is the representative of Indra, see Hopkins, " Religions of India," pp. 360-61.

In the ancient civilization of America one of the most prominent deities was called the " Feathered Serpent," in the Maya language, Kukulkan, Quiche Gukumatz, Aztec Quetzalcoatl, the Pueblo " Mother of Waters". Throughout a very extensive part of America the snake, like the Indian Nâga, is the emblem of rain, clouds, thunder and lightning. But it is essentially and pre-eminently the symbol of rain; and the god who controls the rain, Chac of the Mayas, Tlaloc of the Aztecs, carried the axe and the thunderbolt like his homologues and prototypes in the Old World. In America also we find reproduced in full, not only the legends of the antagonism between the thunder-bird and the serpent, but also the identification of these two rivals in one composite monster, which, as I have already mentioned, is seen the winged disks, both in the Old World and the New.1 Hardly any incident in the history of the Egyptian falcon or the thunder-birds of Babylonia, Greece or India, fails to reappear in America and find pictorial expression in the Maya and Aztec codices.

1 " The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization in the East and in America," Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 1916, Fig. 4, "The Serpent-Bird ".

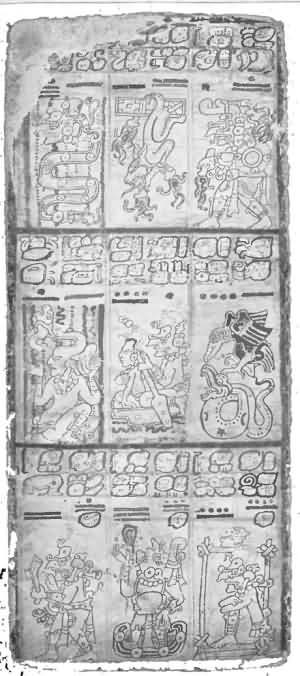

Fig. 13.

A photographic reproduction of the 36th page of the Dresden Maya Codex.

Of the three pictures in the top row one represents the elephant- headed god Chac with a snake's body. He is pouring out rain. The central picture represents the lightning animal carrying fire down from heaven to earth. On the right Chac is shown in human guise carrying thunder weapons in the form of burning torches.

In the second row a goddess sits in the rain : her head is prolonged into that of a bird, holding a fish in its beak. The central picture shows Chac in his boat ferrying a woman across the water from the East. The third illustration depicts the familiar conflict between the vulture and serpent.

In the third row Chac is seen with his axe : in the central picture he is standing in the water looking up towards a rain-cloud; and on the right he is shown sitting in a hut resting from his labours.

What makes America such a rich storehouse of historical data is the fact that it is stretched across the world almost from pole to pole; and for many centuries the jetsam and flotsam swept on to this vast strand has made it a museum of the cultural history of the Old World, much of which would have been lost for ever if America had not saved it. But a record preserved in this manner is necessarily in a highly confused state. For essentially the same materials reached America in manifold forms. The original immigrants into America brought from North-Eastern Asia such cultural equipment as had readied the area east of the Yenesei at the time when Europe was in the Neolithic phase of culture. Then when ancient mariners began to coast along the Eastern Asiatic littoral and make their way to America by the Aleutian route there was a further infiltration of new ideas. But when more venturesome sailors began to navigate the open seas and exploit Polynesia, for centuries, probably from about 300 B.C. to 700 A.D., there was a more or less constant influx of customs and beliefs, which were drawn from Egypt and Babylonia, from the Mediterranean and East Africa, from India and Indonesia, China and Japan, Cambodia and Oceania. One and the same fundamental idea, such as the attributes of the serpent as a water-god, reached America in an infinite variety of guises, Egyptian, Babylonian, Indian, Indonesian, Chinese and Japanese, and from this amazing jumble of confusion the local priesthood of Central America built up a system of beliefs which is distinctively American, though most of the ingredients and the principles of synthetic composition were borrowed from the Old World.

Every possible phase of the early history of the dragon-story and all the ingredients which in the Old World went to the making of it have been preserved in Amaican pictures and legends in a bewildering variety of forms and with an amazing luxuriance of complicated symbolism and picturesque ingenuity. In America, as in India and Eastern Asia, the power controlling water was identified both with a serpent (which in the New World, as in the Old, was often equipped with such inappropriate and arbitrary appendages, as wings, horns and crests) and a god, who was either associated or confused with an elephant. Now many of the attributes of these gods, as personifications of the life-giving powers of water, are identical with those of the Babylonian god Ea and the Egyptian Osiris, and their reputations as warriors with the respective sons and representatives, Mavduk and Horus. The composite animal of Ea-Marduk, the " sea-goat " (the Capricornus of the Zodiac), was also the vehicle of Varuna in India whose relationship to Indra was in some respects analogous to that of Ea to Marduk in Babylonia. The Indian " sea-goat " or Makare, was in fact intimately associated both with Varuna and with Indra. This monster assumed a great variety of forms, such as the crocodile, the dolphin, the sea-serpent or dragon, or combinations of the heads of different animals with a fish's body (Fig. 14). Amongst these we find an elephant-headed form of the makara, which was adopted as far east as Indonesia and as far west as Scotland.

I have already called attention to the part played by the makara, in determining the development of the form of the elephant-headed god in America. Another form of the makara is described in the following American legend, which is interesting also as a mutilated version of the original dragon-story of the Old World.

In 1912 Hernandez translated and published a Maya manuscript 8 which had been written out in Spanish characters in the early days of the conquest of the Americas, but had been overlooked until six ears ago. It is an account of the creation, and includes the following passages : " All at once came the water [? rain] after the dragon was carried away. The heaven was broken up; it fell upon the earth; and they say that Cantul-ti-ku (four gods), the four Baccab, were those who destroyed it. . . . ' The whole world," said ¿lk-Mtc-chek-nale (he who seven rimes makes fruitful), ' proceeded from the seven bosoms of the earth.' And he descended to make fruitful Itsam-kab-ain (the female whale with alligator-feet), when he came down from the central angle of the heavenly region" (p.171).

Fig. 14.

A. The so-called " sea-goat " of Babylonia, a creature compounded of the antelope and fish of Ea.

B. The " sea-goat " as the vehicle of Ea or Marduk.

C to K - a series of varieties of the macara from the Buddhist Rails at Buddha Gaya and Mathura, circa 70 B.C. - 70 A.D., after Cunningham (" Archaeological Survey of India," Vol. Ill, 1873, Plates IX and XXIX).

L. The macara as the vehicle of Varuna, after Sir George Birdwood. It is not difficult to understand how, m the course of the easterly diffusion of culture, such a picture should develop into the Chinese Dragon or the American Elephant-headed God.

Hernandez adds that " the old fishermen of Yucatan still call the whale Itzam : this explains the name of ftzaes, by which the Mayas were known before the founding of Mayapan ".

The close analogy to the Indra-story is suggested by the phrase describing the coming of the water " after the dragon was carried away ". Moreover, the Indian sea-elephant makara, which was confused in the Old World with the dolphin of Aphrodite, and was sometimes also regarded as a crocodile, naturally suggests that the " female whale with the alligator-feet " was only an American version of the old Indian legend.

All this serves, not only to corroborate the inferences drawn from the other sources of information which I have already indicated, but also to suggest that, in addition to borrowing the chief divinities of their pantheon from India, the Maya people's original name was derived from the same mythology.1

1 From the folk-lore of America I have collected many interesting variants of the Indra story and other legends (and artistic designs) of the elephant. I hope to publish these in the near future.

It is of considerable interest and importance to note that in the earliest dated example of Maya workmanship (from Tuxtla, in the Vera Cruz State of Mexico), for which Spinden assigns a tentative date of 235 B.C., an unmistakable elephant figures among the four hieroglyphs which Spinden reproduces (pp. cit., p. 171). A similar hieroglyphic sign is found in the Chinese records of the Early Chow Dynasty (John Ross, "The Origin of the Chinese People," 1916, P. 152).

The use of the numerals four and seven in the narrative translated by Hernandez, as in so many other American documents, is itself, as Mrs. Zelia Nuttall has so conclusively demonstrated,1 a most striking and conclusive demonstration of the link with the Old World.

1 Peabody Museum Papéis, 1901.

Indra was not the only Indian god who was transferred to America for all the associated deities, with the characteristic stories of their exploits,2 are also found depicted with childlike directness of incident, but amazingly luxuriant artistic phantasy, in the Maya and Aztec codices.

2 See, for example, Wilfrid Jackson's " Shells as Evidence of the Migration of Early Culture," pp. 50-66.

We find scattered throughout the islands of the Pacific the familiar stories of the dragon. One mentioned by the Bishop of Wellington refers to a New Zealand dragon with jaws like a crocodile's, which spouted water like a whale, it lived in a fresh-water lake.3 In the same number of the same Journal Sir George Grey gives extracts from a Maori legend of the dragon, which he compares with corresponding passages from Spenser's " Faery Queen ". " Their strict verbal and poetical conformity with the New Zealand legends are such as at first to lead to the impression either that Spenser must have stolen his images and language from the New Zealand poets, or that they must have acted unfairly by the English bard " (p. 362). The Maori legend describes the dragon as "in size large as a monstrous whale, m shape like a hideous lizard; for in its huge head, its limbs, its tail, its scales, its tough skin, its sharp spines, yes, in all these it resembled a lizard " (p.364).

3 " Notes on the Maoris, etc.," Journal of the Zoological Society * vol. i., 1869, p. 368.

Now the attributes of the Chinese and Japanese dragon as the controller of rain, thunder and lightning are identical with those of the American elephant-headed god. it also is associated with the East and with the tops of mountains. It is identified with the Indian Nâga, but the conflict involved in this identification is less obtrusive than it is either in America or in India, in Dravidian India the rulers and the gods are identified with the serpent : but among the Aryans, who were hostile to the Dravidians, the rain-god is the enemy of the Naga. In America the confusion becomes more pronounced because Tlaloc (Chac) represents both Indra and his enemy the serpent. The representation in the codices of his conflict with the serpent is merely a tradition which the Maya and Aztec scribes followed, apparently without understanding its meaning.

In China and Japan the Indra-episode plays a much less prominent part for the dragon is, like the Indian Naga, a beneficent creature, which approximates more nearly to the Babylonian Ea or the Egyptian Osiris. It is not only the controller of water, but the impersonation of water and its life-giving powers : it is identified with the emperor, with his standard, with the sky, and with all the powers that give, maintain, and "prolong life and guard against all kinds of danger to life. In other words, it is the bringer of good luck, the rejuvenator of mankind the giver of immortality.

But if the physiological functions of the dragon of the Far East can thus be assimilated to those of the Indian Naga and the Babylonian and Egyptian Water God, who is also the king, anatomically he is usually represented in a form which can only be regarded as the Babylonian composite monster, as a rule stripped of his wings, though not of his avian feet. *

In America we find preserved in the legends of the Indians an accurate and unmistakable description of the Japanese dragon (which is mainly Chinese in origin). Even Spinden, who "does not care to dignify by refutation the numerous empty theories of ethnic connections between Central America " [and in fact America as a whole] " and the Old World," makes the following statement (in the course of a discussion of the myths relating to horned snakes in California) : " a similar monster, possessing antlers, and sometimes wings, is also very common in Algonkin and Iroquois legends, although rare in art. As a rule the horned serpent is a water spirit and an enemy of the thunder bird. Among the Pueblo Indians the horned snake seems to have considerable prestige in religious belief. ... It lives in the water or in the sky and is connected with rain or lightning."

Thus we find stories of a dragon equipped with those distinctive tokens of Chinese origin, the deer's antlers; and along with it a snake with less specialized horns suggesting the Cerastes of Egypt and Babylonia. A horned viper distantly akin to the Cerastes of the Old World does occur in California; but its " horns " are so insignificant as to make it highly improbable that they could have been in any way responsible for the obtrusive role played by horns in these widespread American stories. But the proof of the foreign origin of these stories is established by the homed serpent's achievements.

It " lives in the water or the sky " like its homologue in the Old World, and it is " a water spirit ". Now neither the Cobra nor the Cerastes is actually a water serpent. Their achievements in the myths therefore have no possible relationship with the natural habits of the real snakes. They are purely arbitrary attributes which they have acquired as the result of a peculiar and fortuitous series of historical incidents.

It is therefore utterly inconceivable and in the highest degree improbable that this long chain of chance circumstances should have happened a second time in America, and have been responsible for the creation of the same bizarre story in reference to one of the rarer American snakes of a localized distribution, whose horns are mere vestiges, which no one but a trained morphologist is likely to have noticed or recognized as such.

But the American horned serpent, like its Babylonian and Indian homologues, is also the enemy of the thunder bird. Here is a further corroboration of the transmission to America of ideas which were the chance result of certain historical events in the Old World, which I have mentioned in this lecture.

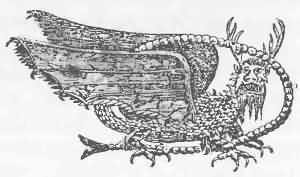

In the figure on page 94 I reproduce a remarkable drawing of an American dragon. If the Algonkin Indians had not preserved legends of a winged serpent equipped with deer's antlers, no value could be as signed to this sketch : but as we know that this particular tribe retains the legend of just such a wonder-beast, we are justified in treating this drawing as something more than a jest.

" Petroglyphs are reported by Mr. John Criley as occurring near Ava, Jackson County, Illinois. The outlines of the characters observed by him were drawn from memory and submitted to Mr. Charles S. Mason, of Toledo, Ohio, through whom they were furnished to the Bureau of Ethnology. Little reliance can be placed upon the accuracy of such drawing, but from the general appearance of the sketches the originals of which they are copies were probably made by one of the middle Algonquin tribes of Indians.1

1 I quote this and the following paragraphs verbatim from Garrick Maliery, " Picture Writing of the American Indians," 10th Annual Report, 1888-89, Bureau of Ethnology (Smithsonian Institute), p. 78.

"The ' Piasa ' rock, as it is generally designated, was referred to by the missionary explorer Marquette in 1675. Its situation was immediately above the city of Alton, Illinois."

Marquette's remarks are translated by Dr. Francis Parkman as follows: -

" On the flat face of a high rock were painted, in red, black, and green, a pair of monsters, each ' as large as a calf, with horns like a deer, red eyes, a beard like a tiger, and a frightful expression of countenance. The face is something like that of a man, the body covered with scales; and the tail so long that it passes entirely round the body, over the head, and between the legs, ending like that of a fish."'

Another version, by Davidson and Struve, of the discovery of > the petroglyph is as follows : -

" Again they (Joliet and Marquette) were floating on the broad bosom of the unknown stream. Passing the mouth of the Illinois, they soon fell into the shadow of a tall promontory, and with great astonishment beheld the representation of two monsters painted on its lofty limestone front. According to Marquette, each of these frightful figures had the face of a man, the horns of a deer, the beard of a tiger, and the tail of a fish so long that it passed around the body, over the head, and between the legs. It was an object of Indian worship and greatly impressed the mind of the pious missionary with the necessity of substituting for this monstrous idolatry the worship of the true God."

A footnote connected with the foregoing quotation gives the following description of the same rock : -

" Near the mouth of the Piasa creek, on the bluff, there is a smooth rock in a cavernous cleft, under an overhanging cliff, on whose face 50 feet from the base, are painted some ancient pictures or hieroglyphics, of great interest to the curious. They are placed in a horizontal line from east to west, representing men, plants and animals. The paintings, though protected from dampness and storms, are in great part destroyed, marred by portions of the rock becoming detached and falling down."

Mr. Me Adams, of Alton, Illinois, says, " The name Piasa is Indian and signifies, in the Illini, the bird which devours men ". He furnishes a spirited pen-and-ink sketch, 12 by 15 inches in size and purporting to represent the ancient painting described by Marquette.

On the picture is inscribed the following in ink : " Made by Wm. Dennis, April 3rd, 1825". The date is in both letters and figures On the top of the picture in large letters are the two words, " FLYING DRAGON ". This picture, which has been kept in the old Gilhani family of Madison county and bears the evidence of its age, is reproduced as Fig. 3.

He also publishes another representation with the following remarks : -

" One of the most satisfactory pictures of the Piasa we have ever seen is in an old German publication entitled ' The Valley of ¿e Mississippi Illustrated. Eighty illustrations from Nature, by H. Lewis from the Falls of St. Anthony to the Gulf of Mexico,' published about the year 1839 by Arenz and Co., Dusseldorf, Germany.

FIG. 3. - WM. DENNIS'S DRAWING OF THE " FLYING DRAGON " DEPICTED ON THE ROCKS

AT PIASA, ILLINOIS.

One of the large full-page plates in this work gives a fine view of the bluff at Alton, with the figure of the Piasa on the face of the rock. It is represented to have been taken on the spot by artists from Germany. . . . In the German picture there is shown just behind the rather dim outlines of the second face a ragged crevice, as though of a fracture. Part of the bluff's face might have fallen and thus nearly destroyed one of the monsters, for in later years writers speak of but one figure. The whole face of the bluff was quarried away in 1846-47."

The close agreement of this account with that of the Chinese and Japanese dragon at once arrests attention. The anatomical peculiarities are so extraordinary that if Pére Marquette's account is trustworthy there is no longer any room for doubt of the Chinese or Japanese derivation of this composite creature. If the account is not accepted we will be driven, not only to attribute to the pious seventeenth-century missionary serious dishonesty or culpable gullibility, but also to credit him with remarkably precise knowledge of Mongolian archaeology. When Aleonkin legends are recalled, however, I think we are bound to accent the missionary's account as substantially accurate.

Minns claims that representations of the dragon are unknown in China before the Han dynasty. But the legend of the dragon is much more ancient. The evidence has been given in full by de Visser.'

He tells us that the earliest reference is found in the Yih King, and shows that the dragon was " a water animal akin to the snake, which [used] to sleep in pools during winter and arises in the spring ". " It is the god of thunder, who brings good crops when he appears in the rice fields (as rain) or in the sky (as dark and yellow clouds), in other words when he makes the rain fertilize the ground " (p. 38).

In the Skit King there is a reference to the dragon as one of the symbolic figures painted on the upper garment of the emperor Hwang Ti (who according to the Chinese legends, which of course are not above reproach, reigned in the twenty-seventh century B.C.). In this ancient literature there are numerous references to the dragon, and not merely to the legends, but also to representations of the benign monster on garments, banners and metal tablets.2 " The ancient texts ... are short, but sufficient to give us the main conceptions of Old China with regard to the dragon. In those early days [just as at present] he was the god of water, thunder, clouds, and rain, the harbinger of blessings, and the symbol of holy men. As the emperors are the holy beings on earth, the idea of the dragon being the symbol of Imperial power is based upon this ancient conception " (pp. cit., p. 42).

In the fifth appendix to the Yih King, which has been ascribed to Confucius, (i.e. three centuries earlier than the Han dynasty mentioned by Mr. Minns), it is stated that " fCien (Heaven) is a horse, Kvuun (Earth) is a cow, Chen {Thunder) is a dragon" (pp. cit., p. 37).3

1 Op. cit., pp. 35 et seq.

'" See de Visser, p. 41.

3 There can be no doubt that the Chinese dragon is the descendant of the early Babylonian monster, and that the inspiration to create it probably reached Shena during the third millennium B.C. by the route indicated in my " Incense and Libations " (Bull. John Rylands Library, vol. iv., No. 2, p. 239). Some centuries later the Indian dragon reached the Far East and Indonesia and mingled with his Babylonian cousin in Japan and China.

The philosopher Hwai Nan Tsze (who died 122 B.C.) declared that the dragon is the origin of all creatures, winged, hairy, scaly, and mailed; and he propounded a scheme of evolution (de Visser, p. 65) He seems to have tried to explain away the fact that he had never actually witnessed the dragon performing some of the remarkable feats attributed to it : " Mankind cannot see the dragons rise : wind and rain assist them to ascend to a great height " (pp. cit., p. 65). Confticius also is credited with the frankness of a similar confession : " As to the dragon, we cannot understand his riding on the wind and clouds and his ascending to the sky. To-day I saw Lao Tsze; is he not like the dragon?" (p. 65).

This does not necessarily mean that these learned men were sceptical of the beliefs 'which tradition had forged in their minds, but that the dragon had the power of hiding itself in a cloak of invisibility, just as clouds (in which the Chinese saw dragons) could be dissipated in the sky. The belief in these powers of the dragon was as sincere as that of learned men of other countries in the beneficent attributes which tradition had taught them to assign to their particular deities. In the passages I have quoted the Chinese scholars were presumably attempting to bridge the gap between the ideas inculcated by faith and the evidence of their senses, in much the same sort of spirit as, for instance, actuated Dean Buckland last century, when he claimed that the glacial deposits of this country afforded evidence in confirmation of the Deluge described in the Book of Genesis.

The tiger and the dragon, the gods of wind and water, are the key stones of the doctrine called fung sami, which Professor de Groot has described in detail.1

He describes it " as a quasi-scientific system, supposed to teach men where and how to build graves, temples, and dwellings, in order that the dead, the gods, and the living may be located therein exclusively, or as far as possible, under the auspicious influences of Nature ". The dragon plays a most important part in this system, being " the chief spirit of water and rain, and at the same time representing one of the four quarters of heaven (i.e. the East, called the Azure Dragon, and the first of the seasons, spring). The word Dragon comprises the high grounds in general, and the water streams which have their sources therein or wind their way through them.2

1 " Religious System of China," vol. iii., chap,

xii., pp. 936-1056.

2 This paragraph is taken almost verbatim from de Visser, pp. 59

and 60.

The attributes thus assigned to the Blue Dragon, his control of . . and streams, his dwelling on high mountains whence they spring, and his association with the East, will be seen to reveal his identity 1 the go-called " god B " of American archaeologists, the elephant- headed god Tlaloc of the Aztecs, Chac of the Mayas, whose more direct parent was Indra.

It is of interest to note that, according to Gerini,1 the word Naga denotes not only a snake but also an elephant. Both the Chinese dragon and the Mexican elephant-god are thus linked with the Naga, who is identified both with Indra himself and Indra's enemy Vritra. This is another instance of those remarkable contradictions that one meets at every step in pursuing the dragon. In the confusion resulting from the blending of hostile tribes and diverse cultures the Aryan deity who, both for religious and political reasons, is the enemy of the Nagas becomes himself identified with a Naga!

1 G. E. Gerini, "Researches on Ptolemy's Geography of Eastern Asia," Asiatic Society's Monographs, No. 1, 1909, p. 146.

I have already called attention (Nature, Jan. 27, 1916) to the fact that the graphic form of representation of the American elephant- headed god was derived from Indonesian pictures of the makara. In India itself the makara (see Fig. 14) is represented in a great variety of forms, most of which are prototypes of different kinds of dragons. Hence the homology of the elephant-headed god with the other dragons is further established and shown to be genetically related to the evolution of the protean manifestations of the dragon's form.

The dragon in China is " the heavenly giver of fertilizing rain " (op. cit., p. 36). In the Shu King " the emblematic figures of the ancients are given as the sun, the moon, the stars, the mountain, the dragon, and the variegated animals (pheasants) which are depicted on the upper sacrificial garment of the Emperor " (p. 39). In the Li Aïthe unicorn, the phoenix, the tortoise, and the dragon are called the [cwoling (p. 39), which de Visser translates " spiritual beings," creatures with enormously strong vital spirit. The dragon possesses the most ling of all creatures (p. 64). The tiger is the deadly enemy of the dragon (p. 42).

The dragon sheds a brilliant light at night (p. 44), usually from his glittering eyes. He is the giver of omens (p. 45), good and bad, rains and floods. The dragon-horse is a vital spirit of Heaven and Earth (p. 58) and also of river water : it has the tail of a huge serpent.

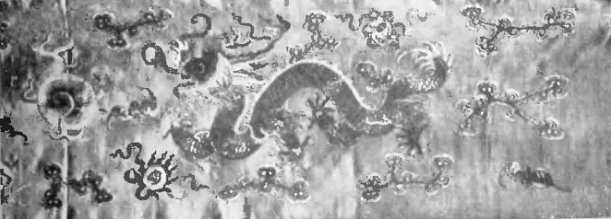

The ecclesiastical vestments of the Wu-ist priests are endowed with magical properties which are considered to enable the wearer to control the order of the world, to avert unseasonable and calamitous events such as drought, untimely and superabundant rainfall, and eclipses These powers are conferred by the decoration upon the dress. Upon the back of the chief vestment the representation of a range of mountains is embroidered as a symbol of the world : on each side (the right and left) of it a large dragon arises above the billows to represent the fertilizing rain. They are surrounded by gold-thread figures representing clouds and spirals typifying rolling thunder.1

1 De Visser, p. 102, and de Groot, vi., p. 1265, Plate XVIII. The reference to " a range of mountains ... as a symbol of the world " re calls the Egyptian representation of the eastern horizon as two hills between which Hathor or her son arises (see Budge, " Gods of the Egyptians," vol. ii., p. 101; and compare Griffith's " Hieroglyphs," p. 30) : the same conception was adopted in Mesopotamia (see Ward, " Seal Cylinders of Western Asia," fig. 412, p. 156) and in the Mediterranean (see Evans, " Mycenasan Tree and Pillar Cult," pp. 37 et sec.). It is a remarkable fact that Sir Arthur Evans, who, upon p. 64 of his memoir, reproduces two drawings of the Egyptian " horizon " supporting the sun's disk, should have failed to recognize in it the prototype of what he calls "the horns of consecration ". Even if the confusion of the " horizon " with a cow's horns was very ancient (for the horns of the Divine Cow supporting the moon made this inevitable), this rationalization should not blind us as to the real origin of the idea, which is preserved in the ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Cretan and Chinese pictures (see Fig. 26, facing p. 188).

A ball, sometimes with a spiral decoration, is commonly represented in front of the Chinese dragon. The Chinese writer Koh Hung tells us that " a spiral denotes the rolling of thunder from which issues a flash of lightning ".2 De Visser discusses this question at some length and refers to Hirth's claim that the Chinese triquetrum, i.e., the well- known three-comma shaped figure, the Japanese müsu-tomoe, the ancient spiral, represents thunder also.3

2 De Visser, p. 103.

Before discussing this question, which involves the consideration of the almost world-wide belief in a thunder-weapon and its relationship to the spiral ornament, the octopus, the pearl, the swastika and triskele, let us examine further the problem of the dragon's ball (see Fig. 15).

3 P. 104, The Chinese triquetrum has a circle in the centre and five or eight commas.

Fig. 15. PHOTOGRAPH OF A CHINESE EMBROIDERY MANCHESTER SCHOOL OF ART REPRESENTING THE DRAGON AND THE PEARL-MOON SYMBOL

De Groot regards the dragon as a thunder-god and therefore, like Hirth, assumes that the supposed thunder-ball is being belched forth and not being swallowed by the dragon. But de Visser, as the result Of a conversation with Mr. Kramp and the study of a Chinese picture in Slacker's "Chats on Oriental China" (1908, p. 54), puts forward the suggestion that the ball is the moon or the pearl-moon which the dragon is swallowing, thereby causing the fertilizing rain. The Chinese themselves refer to the ball as the " precious pearl." which, under the influence of Buddhism in China, was identified with " the pearl that grants all desires" and is under the special protection of the Naga, i.e., the dragon. Arising out of this de Visser puts the conundrum : "Was the ball originally also a pearl, not of Buddhism but of Taoism ? "

In reply to this question I may call attention to the fact that the germs of civilization were first planted in China by people strongly imbued with the belief that the pearl was the quintessence of life giving and prosperity-conferring powers : it was not only identified with the moon, but also was itself a particle of moon-substance which fell as dew into the gaping oyster. It was the very people who held such views about pearls and gold who, when searching for alluvial gold and fresh water pearls in Turkestan, were responsible for transferring these same life-giving properties to jade; and the magical value thus attached to jade was the nucleus, so to speak, around which the earliest civilization of China was crystallized.

As we shall see, in the discussion of the thunder-weapon (p. 121 ), the luminous pearl, which was believed to have fallen from the sky, was homologized with the thunderbolt, with the functions of which its own magical properties were assimilated.

Kramp called de Visser's attention to the fact that the Chinese hieroglyphic character for the dragon's ball is compounded of the signs for jewel and moon, which is also given in a Japanese lexicon as divine pearl, the pearl of the bright moon.

" When the clouds approached and covered the moon, the ancient Chinese may have thought that the dragons had seized and swallowed this pearl, more brilliant than all the pearls of the sea " (de Visser P. 108).

The difficulty de Visser finds in regarding his own theory as wholly satisfactory is, first, the red colour of the ball, and secondly, the spiral pattern upon it. He explains the colour as possibly an attempt to re present the pearl's lustre. But de Visser seems to have overlooked the fact that red and rose-coloured pearls obtained from the conch-shell were used in China and Japan.1

1 Wilfrid Jackson, " Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture," p. 106.

"The spiral is much used in delineating the sacred pearls of Buddhism, so that it might have served also to design those of Taoism; although I must acknowledge that the spiral of the Buddhist pearl goes upward, while the spiral of the dragon is flat " (p. 103).

De Visser sums up the whole argument in these words : -

" These are, however, all mere suppositions. The only facts we know are : the eager attitude of the dragons, ready to grasp and swallow the ball; the ideas of the Chinese themselves as to the ball being the moon or a pearl; the existence of a kind of sacred "moon-pearl "; the red colour of the ball, its emitting flames and its spiral- like form. As the three last facts are in favour of the thunder theory, I should be inclined to prefer the latter. Yet I am convinced that the dragons do not belch out the thunder. If their trying to grasp or swallow the thunder could be explained, I should immediately accept the theory concerning the thunder-spiral, especially on account of the flames it emits. But I do not see the reason why the god of thunder should persecute thunder itself. Therefore, after having given the above facts that the reader may take them into consideration, I feel obliged to say : ' non liquet'" (p. 108).

It does not seem to have occurred to the distinguished Dutch scholar, who has so lucidly put the issue before us, that his demonstration of the fact of the ball being the pearl-moon about to be swallowed by the dragon does not preclude it being also confused with the thunder. Elsewhere in this volume I have referred to the origin of the spiral symbolism and have shown that it became associated with the pearl before it became the symbol of thunder. The pearl-association in fact was one of the links in the chain of events which made the pearl and the spirally-coiled arm of the octopus the sign of thunder.1

1 shall discuss this more fully in " The Birth of Aphrodite ".

It seems quite clear to me that de Visser's pearl-moon theory is the true interpretation. But when the pearl-ball was provided with the spiral, painted red, and given flames to represent its power of emitting light and shining by night, the fact of the spiral ornamentation and of the pearl being one of the surrogates of the thunder-weapon was rationalized into an identification of the ball with thunder and the light it was emitting as lightning. It is, of course, quite irrational for a thunder-god to swallow his own thunder : but popular interpretations of subtle symbolism, the true explanation of which is deeply buried in the history of the distant past, are rarely logical and almost invariably irrelevant.

In his account of the state of Brahmanism in India after the times of the two earlier Vedas, Professor Hopkins2 throws light upon the real significance of the ball in the dragon-symbolism. " Old legends are varied. The victory over Vritra is now expounded thus : Indra, who slays Vritra, is the sun. Vritra is the moon, who swims into the sun's mouth on the night of the new moon. The sun rises after swallowing him, and the moon is invisible because he is swallowed. The sun vomits out the moon, and the latter is then seen in the west, and increases again, to serve the sun as food, in another passage it is said that when the moon is invisible he is hiding in plants and waters."

This seems to clear away any doubt as to the significance of the ball. It is the pearl-moon, which is both swallowed and vomited by the dragon.

The snake takes a more obtrusive part in the Japanese than in the Chinese dragon and it frequently manifests itself as a god of the sea. The old Japanese sea-gods were often female water-snakes. The cultural influences which reached Japan from the south by way of Indonesia - many centuries before the coming of Buddhism - naturally emphasized the serpent form of the dragon and its connexion with the ocean.

But the river-gods, or " water-fathers," were real four-footed dragons identified with the dragon-kings of Chinese myth, but at the time were strictly homologous with the Naga Rajas or cobra- kings of India.

The Japanese " Sea Lord " or " Sea Snake " was also called " Abundant-Pearl-Prince," who had a magnificent palace at the bottom of the sea. His daughter ("Abundant-Pearl-Princess") married a youth whom she observed, reflected in the well, sitting on a cassia tree near the castle gate. Ashamed at his presence at her lying-in she was changed into a want or crocodile (de Visser, p. 139), elsewhere described as a dragon (makara). De Visser gives it as his opinion that the want is " an old Japanese dragon, or serpent-shaped sea-god, and the legend is an ancient Japanese tale, dressed in an Indian garb by later generations " (p. 140). He is arguing that the Japanese dragon existed long before Japan came under Indian influence. But he ignores the fact that at a very early date both India and China were diversely influenced by Babylonia, the great breeding place of dragons; and, secondly, that Japan was influenced by Indonesia, and through it by the West, for many centuries before the arrival of such later Indian legends as those relating to the palace under the sea, the castle gate and the cassia tree. As Aston (quoted by de Visser) remarks, all these incidents and also the well that serves as a mirror, " form a combination not unknown to European folklore".

After de Visser had given his own views, he modified them (on p. 141) when he learned that essentially the same dragon-stories had been recorded in the Kei Islands and Minahassa (Celebes). In the light of this new information he frankly admits that "the re semblance of several features of this myth with the Japanese one is so striking, that we may be sure that the latter is of Indonesian origin." He goes further when he recognizes that " probably the foreign invaders, who in prehistoric times conquered Japan, came from Indonesia, and brought the myth with them" (p. 141). The evidence recently brought together by W. J. Perry in his book "The Megalithic Culture of Indonesia " makes it certain that the people of Indonesia in turn got it from the West.

An old painting reproduced by F. W. K. Muller, who called de Visser's attention to these interesting stories, shows Hohodemi the youth on the cassia tree who married the princess) returning home mounted on the back of a crocodile, like the Indian Varuna upon the makara in a drawing reproduced by the late Sir George Birdwood.1

1 See Fig. 14.

The want or crocodile thus introduced from India, via Indonesia, is really the Chinese and Japanese dragon, as Aston has claimed. Aston refers to Japanese pictures in which the Abundant-Pearl-Prince and his daughter are represented with dragon's heads appearing over their human ones, but in the old Indonesian version they maintain their forms as want or crocodiles.

The dragon's head appearing over a human one is quite an Indian motive, transferred to China and from there to Korea and Japan (de Vissa', p. 142), and, I may add, also to America.

[Since the foregoing paragraphs have been printed, the Curator of the Liverpool Museum has kindly called my attention to a remarkable series of Maya remains in the collection under his care, which were obtained in the course of excavations made by Mr. T. W. F. Gann, M.R.C.S., an officer in the Medical Service of British Honduras (see his account of the excavations in Part II. of the 19th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution of Washington). Among them is a pottery figure of a want or makara in the form of an alligator, equipped with diminutive deer's horns (like the dragon of Eastern Asia); and its skin is studded with circular elevations, presumably meant to represent the spots upon the star-spangled " Celestial Stag" of the Aryans (p. 130). As in the Japanese pictures mentioned by Aston, a human head is seen emerging from the creature's throat. It affords a most definite and convincing demonstration of the sources of American culture.]

The jewels of flood and ebb in the Japanese legends consist of the pearls of flood and ebb obtained from the dragon's palace at the bottom of the sea. By their aid storms and floods could be created to destroy enemies or calm to secure safety for friends. Such stories are the logical result of the identification of pearls with the moon, the influence of which upon the tides was probably one of the circumstances which was responsible for bringing the moon into the circle of the great scientific theory of the life-giving powers of water. This in turn played a great, if not decisive, part in originating the earliest belief in a sky world, or heaven.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE DRAGON.

The American and Indonesian dragons can be referred back primarily to India, the Chinese and Japanese varieties to India and Babylonia. The dragons of Europe can be traced through Greek channels to the same ultimate source. But the cruder dragons of Africa are derived either from Egypt, from the AEgean, or from India All dragons that strictly conform to the conventional idea of what such a wonder-beast should be can be shown to be sprung from the fertile imagination of ancient Sumer, the "great breeding place of monsters" (Minns).

But the history of the dragon's evolution and transmission to other countries is full of complexities; and the dragon-myth is made up of many episodes, some of which were not derived from Babylonia.

In Egypt we do not find the characteristic dragon and dragon- story. Yet all of the ingredients out of which both the monster and the legends are compounded have been preserved in Egypt, and in perhaps a more primitive and less altered form than elsewhere. Hence, if Egypt does not provide dragons for us to dissect, it does supply us with the evidence without which the dragon's evolution would be quite unintelligible.

Egyptian literature affords a clearer insight into the development of the Great Mother, the Water God, and the Warrior Sun God than we can obtain from any other writings of the origin of this fundamental stratum of deities. And m the three legends : The Destruction of Mankind, The Story of the Winged Disk, and The Conflict between Horus and Set, it has preserved the germs of the great Dragon Saga. Babylonian literature has shown us how this raw material was worked up into the definite and familiar story, as well as how the features of a variety of animals were blended to form the composite monster. India and Greece, as well as more distant parts of Africa, Europe, and Asia, and even America have preserved many details that have been lost in the real home of the monster.

In the earliest literature that has come down to us from antiquity a clear account is given of the original attributes of Osiris. " Horus comes, he recognizes his father in thee [Osiris], youthful in thy name of ' Fresh Water '." " Thou art indeed the Nile, great on the fields at the beginning of the seasons; gods and men live by the moisture that is in thee. He is also identified with the inundation of the river. " it ' Unis [the dead king identified with Osiris] who inundates the land." He also brings the wind and guides it. It is the breath of life which rises the king from the dead as an Osiris. The wine-press god comes to Osiris bearing wine-juice and the great god becomes " Lord of the overflowing wine " : he is also identified with barley and with the beer made from it. Certain trees also are personifications of the god.

But Osiris was regarded not only as the waters upon earth, the rivers and streams, the moisture in the soil and in the bodies of animals and plants, but also as " the waters of life that are in the sky ".

" As Osiris was identified with the waters of earth and sky, he may even become the sea and the ocean itself. We find him addressed thus : ' Thou art great, thou art green, in thy name of Great Green (Sea); lo, thou art round as the Great Circle (Okeanos); lo, thou art turned about, thou art round as the circle that encircles the Haunebu {AEgeans)."

This series of interesting extracts from Professor Breasted's " Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt " (pp. 18-26) gives the earliest Egyptians' own ideas of the attributes of Osiris. The Babylonians regarded Ea in almost precisely the same light and endowed him with identical powers. But there is an important and significant difference between Osiris and.Ea. The former was usually represented as a man, that is, as a dead king, whereas Ea was represented as a man wearing a fish-skin, as a fish, or as the composite monster with a fish's body and tail, which was the prototype of the Indian makara and " the father of dragons ".

In attempting to understand the creation of the dragon it is important to remember that, although Osiris and Ea were regarded primarily as personifications of the beneficent life-giving powers of water, as the bringers of fertility to the soil and the givers of life and immortality to living creatures, they were also identified with the destructive forces of water, by which men were drowned or their welfare affected in various ways by storms of sea and wind.

Thus Osiris or the fish-god Ea could destroy mankind. In other words the fish-dragon, or the composite monster formed of a fish and an antelope, could represent the destructive forces of wind and water. Thus even the malignant dragon can be the homologue of the usually beneficent gods Osiris and Ea, and their Aryan surrogates Mazda}) and Varuna.

By a somewhat analogous process of archaic rationalization respectively of Osiris and Ea, the sun-gods Horns and Mardul acquired a similarly confused reputation. Although their outstanding achievements were the overcoming of the powers of evil, and, as the givers of light, conquering darkness, their character as warriors made them also powers of destruction. The falcon of Horus thus became also a symbol of chaos, and as the thunder-bird became the most obtrusive feature in the weird anatomy of the composite Mesopotamian dragon and his more modern bird-footed brood, which ranges from Western Europe to the Far East of Asia and America.

That the sun-god derived his functions directly or indirectly from Osiris and Hathor is shown by his most primitive attributes, for in " the earliest sun-temples at Abusir, he appears as the source of life and increase". "Men said of him: 'Thou hast driven away the storm, and hast expelled the rain, and hast broken up the clouds. Horus was in fact the son of Osiris and Hathor, from whom he derived his attributes. The invention of the sun-god was not, as most scholars pretend, an attempt to give direct expression to the fact that the sun is the source of fertility. That is a discovery of modern science. The sun-god acquired his attributes secondarily (and for definite historical reasons) from his parents, who were responsible for his birth.

The quotation from the Pyramid Texts is of special interest as an illustration of one of the results of the assimilation of the idea of Osiris as the controller of water with that of a sky-heaven and a sun-god. The sun-god's powers are rationalized so as to bring them into conformity with the earliest conception of a god as a power controlling water.

Breasted attempts to interpret the statements concerning the storm and rain-clouds as references to the enemies of the sun, who steal the sky- god's eye, i.e., obscure the sun or moon. The incident of Horus's lots of an eye, which looms so large in Egyptian legends, is possibly more closely related to the earliest attempts at explaining eclipses of the sun and moon, the " eyes " of the sky. The obscuring of the sun and moon by clouds is a matter of little significance to the Egyptian : but the modern Egyptian fellah, and no doubt his predecessors also. regarded eclipses with much concern. Such events excite great alarm, - the peasants consider them as actual combats between the powers of good and evil.

In other countries where rain is a blessing and not, as. in Egypt, merely an unwelcome inconvenience, the clouds play a much more prominent part in the popular beliefs. In the Rig-Veda the power that holds up the clouds is evil : as an elaboration of the ancient Egyptian conception of the sky as a Divine Cow, the Great Mother, the Aryan Indians regarded the clouds as a herd of cattle which the Vedic warrior-god Indra (who in this respect is the homologue of the Egyptian warrior Horus) stole from the powers of evil and bestowed upon mankind. In other words, like Horus, he broke up the clouds and brought rain.

The antithesis between the two aspects of the character of these ancient deities is most pronounced in the case of the other member of this most primitive Trinity, the Great Mother. She was the great beneficent giver of life, but also the controller of life, which implies that she was the death-dealer. But this evil aspect of her character developed only under the stress of a peculiar dilemma in which she was placed. On a famous occasion in the very remote past the great Giver of Life was summoned to rejuvenate the aging king. The only elixir of life that was known to the pharmacopoeia of the times was human blood : but to obtain this life-blood the Giver of Life was compelled to slaughter mankind. She thus became the destroyer of man kind in her lioness avatar as Sekhet.

The earliest known pictorial representation of the dragon consists of the forepart of the sun-god's falcon or eagle united with the hindpart of the mother-goddess's lioness. The student of modern heraldry would not regard this as a dragon at all, but merely a gryphon or griffin. A recent writer on heraldry has complained that, " in spite of frequent corrections, this creature is persistently confused in the popular mind with the dragon, which is even more purely imaginary.1 But the investigator of the early history of these wonder-beasts is compelled, even at the risk of incurring the herald's censure, to regard the gryphon as one of the earliest known tentative efforts at dragon-making. But though the fish, the falcon or eagle, and the composite eagle-lion

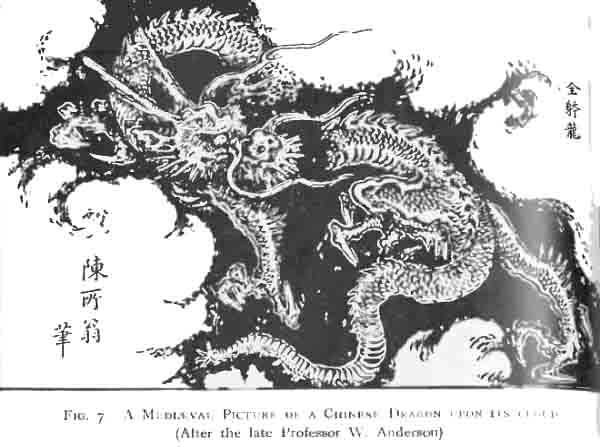

monster are early known pictorial representations of the dragon, g0od or bad, the serpent is probably more ancient still (Fig. 2).1 G. W. Eve, " Decorative Heraldry," 1897, p. 35.

The earliest form assumed by the power of evil was the serpent : but it is important to remember that, as each of the primary deities can be a power of either good or evil, any of the animals representing them can symbolize either aspect. Though Hathor in her cow manifestation is usually benevolent and as a lioness a power of destruction, the cow may become a demon in certain cases and the lioness a kindly creature. The falcon of Horus (or its representatives, eagle, hawk, woodpecker, dove, redbreast, etc) may be either good or bad : so also the gazelle (antelope or deer), the crocodile, the fish, or any of the menagerie of creatures that enter into the composition of good or bad demons.

" The Nagas are semi-divine serpents which very often assume human shapes and whose kings live with their retinues in the utmost luxury in their magnificent abodes at the bottom of the sea or in rivers or lakes. When leaving the Naga world they are in constant danger of being grasped and killed by the gigantic semi-divine birds, the Garudas, which also change themselves into men " (de Visser, p. 7).

" The Nagas are depicted in three forms : common snakes, guarding jewels; human beings with four snakes in their necks; and winged sea-dragons, the upper part of the body human, but with a horned, ox-like head, the lower part of the body that of a coiling-dragon. Here we find a link between the snake of ancient India and the four- legged Chinese dragon " (p. 6), hidden in the clouds, which the dragon himself emitted, like a modern battleship, for the purpose of rendering himself invisible. In other words, the rain clouds were the dragon's breath. The fertilizing rain was thus in fact the vital essence of the dragon, being both water and the breath of life.

" We find the Naga king not only in the possession of numberless jewels and beautiful girls, but also of mighty charms, bestowing super natural vision and hearing. The palaces of the Naga kings are always described as extremely splendid, abounding with gold and silver and precious stones, and the Naga women, when appearing in human shape, were beautiful beyond description " (p. 9).