The Evolution Of The Dragon By G. Elliot Smith

M.A., M.D., F.R.S.

Professor Of Anatomy In The University Of Manchester

1919

PREFACE

SOME explanation is due to the reader of the form and scope of these elaborations of the lectures which I have given at the John Rylands Library during the last three winters.

They deal with a wide range of topics, and the thread which binds them more or less intimately into one connected story is only imperfectly expressed in the title "The Evolution of the Dragon ".

The book has been written in rare moments of leisure snatched from a variety of arduous war-time occupations; and it reveals only too plainly the traces of this disjointed process of composition. On 23 February, 1915, I presented to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society an essay on the spread of certain customs and beliefs in ancient times under the title "On the Significance of the Geographical Distribution of the Practice of Mummification, "and in my Rylands Lecture two weeks later I summed up the general conclusions.[1]

In view of the lively controversies that followed the publication of the former of these addresses, I devoted my next Rylands Lecture (9 February, 1916) to the discussion of "The Relationship of the Egyptian Practice of Mummification to the Development of Civilization ". In preparing this address for publication in the Bulletin some months later so much stress was laid upon the problems of "Incense and Libations "that I adopted this more concise title for the elaboration of the lecture which forms the first chapter of this book. This will explain why so many matters are discussed in that chapter which have little or no connexion either with "Incense and Libations " or with "The Evolution of the Dragon ".

[1] The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilisation in the East and in America, "Bulletin of the John R viands Library, January-March, 1916.

The study of the development of the belief in water's life-giving attributes, and their personification in the gods Osiris, Ea, Soma [Haoma] and Varuna, prepared the way for the elucidation of the history of "Dragons and Rain Gods "in my next lecture (Chapter II).

What played a large part in directing my thoughts dragon-wards was the discussion of certain representations of the Indian Elephant upon Precolumbian monuments in, and manuscripts from, Central America (Nature, 25 Nov., 1915; 16 Dec., 1915; and 27 Jan., 1916). For in the course of investigating the meaning of these remarkable designs I discovered that the Elephant-headed rain-god of America had attributes identical with those of the Indian Indra (and of Varuna and Soma) and the Chinese dragon. The investigation of these identities established the fact that the American rain-god was transmitted across the Pacific from India via Cambodia.

The intensive study of dragons impressed upon me the importance of the part played by the Great Mother, especially in her Babylonian avatar as Tiamat, in the evolution of the famous wonder-beast. Under the stimulus of Dr. Rendel Harris's Rylands Lecture on "The Cult of Aphrodite, "I therefore devoted my next address ( 14 November, 1917) to the "Birth of Aphrodite "and a general discussion of the problems of Olympian obstetrics.

Each of these addresses was delivered as an informal demonstration of large series of lantern projections; and, as Mr. Guppy insisted upon the publication of the lectures in the Bulletin, it became necessary, as a rule, many months after the delivery of each address, to rearrange my material and put into the form of a written narrative the story which had previously been told mainly by pictures and verbal comments upon them.

In making these elaborations additional facts were added and new points of view emerged, so that the printed statements bear little re semblance to the lectures of which they pretend to be reports. Such transformations are inevitable when one attempts to make a written report of what was essentially an ocular demonstration, unless every one of the numerous pictures is reproduced.

Each of the first two lectures was printed before the succeeding lecture was set up in type. For these reasons there is a good deal of repetition, and in successive lectures a wider interpretation of evidence mentioned in the preceding addresses. Had it been possible to revise book at one time, and if the pressure of other duties had permitted me to devote more time to the work, these blemishes might have been eliminated and a coherent story made out of what is little more than a collection of data and tags of comment. No one is more conscious than the writer of the inadequacy of this method of presenting an argument of such inherent complexity as the dragon story : but my obligation to the Rylands Library gave me no option in the matter : I had to attempt the difficult task in spite of all the unpropitious circumstances. This book mu? be regarded, then, not as a coherent argument, but merely as some of the raw material for the study of the dragon's history.

In my lecture (13 November, 1918) on "The Meaning of Myths, "which will be published in the Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, I have expounded the general conclusions that emerge from the studies embodied in these three lectures; and in my forthcoming book, "The Story of the Flood, "I have submitted the whole mass of evidence to examination in detail, and attempted to extract from it the real story of mankind's age-long search for the elixir of life.

In the earliest records from Egypt and Babylonia it is customary to portray a king's beneficence by representing him initiating irrigation works. In course of time he came to be regarded, not merely as the giver of the water which made the desert fertile, but as himself the personification and the giver of the vital powers of water. The fertility of the land and the welfare of the people thus came to be regarded as dependent upon the king's vitality. Hence it was not illogical to kill him when his virility showed signs of failing and so imperilled the country's prosperity. But when the view developed that the dead king acquired a new grant of vitality in the other world he became the god Osiris, who was able to confer even greater boons of life-giving to the land and people than was the case before. He was the Nile, and he fertilized the land The original dragon was a beneficent creature, the personification of water, and was identified with kings and gods.

But the enemy of Osiris became an evil dragon, and was identified with Set.

The dragon-myth, however, did not really begin to develop until an aging king refused to be slain, and called upon the Great Mother, as the giver of life, to rejuvenate him. Her only elixir was human blood; and to obtain it she was compelled to make a human sacrifice. Her murderous act led to her being compared with and ultimately identified with a man-slaying lioness or a cobra. The story of the slaying of the dragon is a much distorted rumour of this incident; and in the process of elaboration the incidents were subjected to every kind of interpretation and "also confusion with the legendary account of the conflict between Horus and Set.

When a substitute was obtained to replace the blood the slaying of a human victim was no longer logically necessary : but an explanation had to be found for the persistence of this incident in the story. Man kind (no longer a mere individual human sacrifice) had become sinful and rebellious (the act of rebellion being complaints that the king or god was growing old) and had to be destroyed as a punishment for this treason. The Great Mother continued to act as the avenger of the king or god. But the enemies of the god were also punished by Horus in the legend of Horus and Set. The two stories hence be came confused the one with the other. The king Horus took the place of the Great Mother as the avenger of the gods. As she was identified with the moon, he became the Sun-god, and assumed many of the Great Mother's attributes, and also became her son. in the further development of the myth, when the Sun-god had completely usurped his mother's place, the infamy of her deeds of destruction seems to have led to her being confused with the rebellious men who were now called the followers of Set, Horus's enemy. Thus an evil dragon emerged from this blend of the attributes of the Great Mother and Set. This is the Babylonian Tiamat. From the amazingly complex jumble of this tissue of confusion all the incidents of the dragon- myth were derived.

When attributes of the Water-god or his enemy became assimilated with those of the Great Mother and the Warrior Sun-god, the animals with which these deities were identified came to be regarded individually and collectively as concrete expressions of the Water-god's powers. Thus the cow and the gazelle, the falcon and the eagle, the lion and the serpent, the fish and the crocodile became symbols of the life giving and the life-destroying powers of water, and composite monsters or dragons were invented by combining parts of these various creatures to express the different manifestations of the vital powers of water. The process of elaboration of the attributes of these monsters led to the development of an amazingly complex myth : but the story became still further involved when the dragon's life-controlling powers became confused with man's vital spirit and identified with the good or evil genius which was regarded as the guest, welcome or unwelcome, of every individual's body, and the arbiter of his destiny. In my remarks on the ka and the fravashi I have merely hinted at the vast complexity of these elements of confusion.

Had I been familiar with [Archbishop] Söderblom's important monograph,[1] when I was writing Chapters I and III, I might have at tempted to indicate how vital a part the confusion of the individual genius with the mythical wonder-beast has played in the history of the myths relating to the latter. For the identification of the dragon with the vital spirit of the individual explains why the stories of the former appealed to the selfish interest of every human being. At the time the lecture on "Incense and Libations "was written, I had no idea that the problems of the ka and tine fravashi had any connexion with those relating to the dragon. But in the third chapter a quotation from Professor Langdon's account of "A Ritual of Atonement for a Babylonian King "indicates that the Babylonian equivalent of the ka and the fravashi, "my god who walks at my side, "presents many points of affinity to a dragon.

[1] Nathan Söderblom, "Les Fravashis Etude sur les Traces dans le Mazdéisme d'une Ancienne Conception sur la Survivance des Morts, "Paris, 1899.

When in the lecture on "Incense and Libations "I ventured to make the daring suggestion that the ideas underlying the Egyptian conception of the ka were substantially identical with those entertained by the Iranians in reference to the fravashi, I was not aware of the fact that such a comparison had already been made. In [Archbishop] Söderblom's monograph, which contains a wealth of information in corroboration of the views set forth in Chapter I, the following statement occurs : "L'analyse, faite par M. Brede-Kristensen (Ægypternes forestillinger om livet efter döden, 14 ss. Kristiania, 1896) du ka Ægyptien, jette une vive lumiere sur notre question, par la frappante analogie qui semble exister entre le sens originaire de ces deux termes ka et fravashi "(p. 58, note 4). "La similitude entre le ka et la fravashi a été signalée déja par Nestor Lhote, Lettres écrites d'Egypte, note, selon Maspero, Études de mythologie et d'archéo logie égyptiennes, I, 47, note 3. "

In support of the view, which I have submitted in Chapter I, that the original idea of fat fravashi, like that of the ka, was suggested by the placenta and the foetal membranes, I might refer to the specific statement (Farvardin-Yasht. XXIII, I) that "les fravashis tiennent en ordre l'enfant dans le sein de sa móre et l'enveloppent de sorte qu'il ne meurt pas "(pp. cit., Söderblom, p. 4l, note I). The fravashi "nourishes and protects "(p. 57) : it is "the nurse "(p. 58) : it is always feminine (p. 58). It is in fact the placenta, and is also associated with the functions of the Great Mother.

"Nous voyons dans fravashi une personification de la force vitale, conservée et exercée aussi aprés la mort. La fravashi est le principe de vie, la faculté qu'a l'homme de se soutenir par la nourriture, de manger, d'absorber et ainsi d'exister et de se développer. Cette etymologic et le r óle attribute a la fravashi dans le développement de l'embryon, des animaux, des plantes rappellent en quelque sorte, comme le remarque M. Foucher, l'idée directrice de Claude Bernard. Seulement la fravashi n'a jamais été une abstraction. La fravashi est une puissance vivante, un hoimtnculus in homine, un ótre personnifié comme du reste toutes les sources de vie et de mouvement que l'homme non civilisé apercoit dans son organisme.

Il ne faut pas non plus considérer la fravashi comme un double de l'homme, elle en est plut ót une partie, un h óte intime qui continue son existence aprés la mort aux memes conditions qu'avant, et lui oblige les vivants a lui fournir les aliments nécessaires "(pp. cit., p 59)

Thus the fravashi has the same remarkable associations with nourishment and placental functions as the ka. As a further suggestion of its connexion with the Great Mother as the inaugurator of the year, and in virtue of her physiological (uterine) functions the moon-controlled measurer of the month, it is important to note that "Le 19e jour de chaque mois est également consecré aux fravashis en général. Le premier mois porte aussi le nom de Farvardin. Quant aux formes des fetes mensuelles, elles semblent conformes a celles que nous allons rappeler [les fetes célébrées en l'honneur des mortes] "(pp. cit., p. 10).

But the fravashi was not only associated with the Great Mother, but also with the Water-god or Good Dragon, for it controlled the waters of irrigation and gave fertility to the soil (pp. cit., p. 36). The fravashi was also identified with the third member of the primitive Trinity, the Warrior Sun-god, not merely in the general sense as the adversary of the powers of evil, but also in the more definite form of the Winged Disk (pp. cit., pp. 67 and 68).

In all these respects fat fravashi is brought into close association with the dragon, so that in addition to being "the divine and immortal element "(pp. cit., p. 51), it became the genius or spirit that possesses a man and shapes his conduct and regulates his behaviour. It was in fact the expression of a crude attempt on the part of the early psychologists of Iran to explain the working of the instinct of self-preservation.

In the text of Chapters I and III I have referred to the Greek, Babylonian, Chinese, and Melanesian variants of essentially the same conception. Söderblom refers to an interesting parallel among the Karens, whose kelah corresponds to the Iranian fravashi (p. 54, Note 2: compare also A. E. Crawley, "The Idea of the Soul, " 1909).

In the development of the dragon-myth astronomical factors played a very obtrusive part : but I have deliberately refrained from entering into a detailed discussion of them, because they were not primarily the real causal agents in the origin of the myth. When the conception of a sky-world or a heaven became drawn into the dragon story it came to play so prominent a part as to convince most writers that the myth was primarily and essentially astronomical. But it is clear that origin- ally the myth was concerned solely with the regulation of irrigation systems and the search upon earth for an elixir of life.

When I put forward the suggestion that the annual inundation of the Nile provided the information for the first measurement of the year, I was not aware of the fact that Sir Norman Lockyer ( "The Dawn of Astronomy, "1894, p. 209), had already made the same claim and substantiated it by much fuller evidence than I have brought together here.

In preparing these lectures I have received help from so large a number of correspondents that it is difficult to enumerate all of them. But I am under a special debt of gratitude to Dr. Alan Gardiner for calling my attention to the fact that the common rendering of the Egyptian word didi as "mandrake "was unjustifiable, and to Mr. F. LI. Griffith for explaining its true meaning and for lending me the literature relating to this matter. Miss Winifred M. Crompton, the Assistant Keeper of the Egyptian Department in the Manchester Museum, gave me very material assistance by bringing to my attention some very important literature which otherwise would have been over looked; and both she and Miss Dorothy Davison helped me with the drawings that illustrate this volume. Mr. Wilfrid Jackson gave me much of the information concerning shells and cephalopods which forms such an essential part of the argument, and he also collected a good deal of the literature which I have made use of. Dr. A. C. Haddon, F.R.S., of Cambridge, lent me a number of books and journals which I was unable to obtain in Manchester; and Mr. Donald A. Mackenzie, of Edinburgh, has poured in upon me a stream of information, especially upon the folklore of Scotland and India. Nor must I forget to acknowledge the invaluable help and forbearance of Mr. Henry Guppy, of the John Rylands Library, and Mr. Charles W. E. Leigh, of the University Library. To all of these and to the still larger number of correspondents who have helped me I offer my most grateful thanks.

During the three years in which these lectures were compiled I have been associated with Dr. W. H. R. Rivers, F.R.S., and Mr. T. H. Pear in their psychological work in the military hospitals, and the influence of this interesting experience is manifest upon every page of this volume.

But perhaps the most potent factor of all in shaping my views and directing my train of thought has been the stimulating influence of Mr. W. J. Perry's researches, which are converting ethnology into a real science and shedding a brilliant light upon the early history of civilization.

G. ELLIOT SMITH.

9 December, 1918.

CHAPTER I. INCENSE AND LIBATIONS *

* An elaboration of a Lecture on the relationship of the Egyptian practice of mummification to the development of civilization delivered in the John Rylands Library, on 9 February, 1916.

The dragon was primarily a personification of the life-giving and life- destroying powers of -water. This chapter is concerned with the genesis of this biological theory of water and its relationship to the other germs of civilization.

IT is commonly assumed that many of the elementary practices of civilization, such as the erection of rough stone buildings, whether houses, tombs, or temples, the crafts of the carpenter and the stonemason, the carving of statues, the customs of pouring out libations or burning incense, are such simple and obvious procedures that any people might adopt them without prompting or contact of any kind with other populations who do the same sort of things. But if such apparently commonplace acts be investigated they will be found to have a long and complex history.

None of these things that seem so obvious to us was attempted until a multitude of diverse circumstances became focussed in some particular community, and constrained some individual to make the discovery. Nor did the quality of obviousness become apparent even when the enlightened discoverer had gathered up the threads of his predecessor's ideas and woven them into the fabric of a new invention. For he had then to begin the strenuous fight against the opposition of his fellows before he could induce them to accept his discovery. He had, in fact, to contend against their preconceived ideas and their lack of appreciation of the significance of 'the progress he had made before he could persuade them of its "obviousness ". That is the history of most inventions since the world began.

But it is begging the question to pretend that because tradition has made such inventions seem simple and obvious to us it is unnecessary to inquire into their history or to assume that any people or any individual simply did these things without any instruction when the spirit moved it or him so to do.

The customs of burning incense and making libations in religious ceremonies are so widespread and capable of being explained in such plausible, though infinitely diverse, ways that it has seemed unnecessary to inquire more deeply into their real origin and significance. For example, Professor Toy[1] disposes of these questions in relation to incense in a summary fashion. He claims that "when burnt before the deity "it is "to be regarded as food, though in course of time, when the recollection of this primitive character was lost, a conventional significance was attached to the act of burning. A more refined period demanded more refined food for the gods, such as ambrosia and nectar, but these also were finally given up. "

[1] "Introduction to the History of Religions, "p. 486.

This, of course, is a purely gratuitous assumption, or series of assumptions, for which there is no real evidence. Moreover, even if there were any really early literature to justify such statements, they explain nothing. Incense-burning is just as mysterious if Prof. Toy's claim be granted as it was before.

But a bewildering variety of other explanations, for all of which the merit of being "simple and obvious "is claimed, have been suggested. The reader who is curious about these things will find a luxurious crop of speculations by consulting a series of encyclopaedias.[2]

2 He might start upon this journey of adventure by reading the article on "Incense "in Hastings' Encylopiadia of Religion and Ethics.

I shall content myself by quoting only one more. "Frankincense and other spices were indispensable in temples where bloody sacrifices formed part of the religion. *The atmosphere of Solomon's temple must have been that of a sickening slaughter-house, and the fumes of incense could alone enable the priests and worshippers to support it. This would apply to thousands of other temples through Asia, and doubtless the palaces of kings and nobles suffered from uncleanliness and insanitary arrangements and required an antidote to evil smells to make them endurable. "[3]

* Samuel Laing, "Human Origins, "Revised by Edward Clodd, 1903, p. 38.

It is an altogether delightful anachronism to imagine that religious ritual in the ancient and aromatic East was inspired by such squeamishness as a British sanitary inspector of the twentieth century might experience !

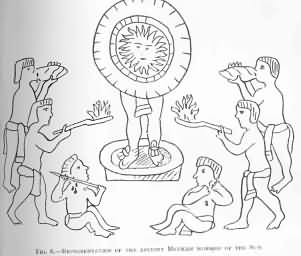

FIG. 1 ”THE CONVENTIONAL EGYPTIAN REPRESENTATION OF THE BURNING OF INCENSE AND THE POURING OF LIBATIONS

Period of the New Empire after Lepsius

But if there are these many diverse and mutually destructive reasons in explanation of the origin of incense-burning, it follows that the meaning of the practice cannot be so "simple and obvious ".

For scholars in the past have been unable to agree as to the sense in which these adjectives should be applied.

But no useful purpose would be served by enumerating a collection of learned fallacies and exposing their contradictions when the true explanation has been provided in the earliest body of literature that has come down from antiquity. I refer to the Egyptian "pyramid Texts ".

Before this ancient testimony is examined certain general principles involved in the discussion of such problems should be considered. In this connexion it is appropriate to quote the apt remarks made, in reference to the practice of totemism, by Professor Sollas.[1] "If it is difficult to conceive how such ideas . . . originated at all, it is still more difficult to understand how they should have arisen repeatedly and have developed in much the same way among races evolving independently in different environments. It is at least simpler to suppose that all [of them] have a common source . . . and may have been carried ... to remote parts of the world. "

I do not think that anyone who conscientiously and without bias examines the evidence relating to incense-burning, the arbitrary details of the ritual and the peculiar circumstances under which it is practised in different countries, can refuse to admit that so artificial a custom must have been dispersed throughout the world from some one centre where it was devised.

[1] "Ancient Hunters, "2nd Edition, pp. 234 and 235.

The remarkable fact that emerges from an examination of these so-called "obvious explanations "of ethnological phenomena is the failure on the part of those who are responsible for them to show any adequate appreciation of the nature of the problems to be solved. They know that incense has been in use for a vast period of time, and that the practice of burning it is very widespread. They have been so familiarized with the custom and certain more or less vague excuses for its perpetuation that they show no realization of how strangely irrational and devoid of obvious meaning the procedure is. The reasons usually given in explanation of its use are for the most part merely paraphrases of the traditional meanings that in the course of history have come to be attached to the ritual act or the words used to designate it. Neither the ethnologist nor the priestly apologist will, as a rule, admit that he does not know why such ritual acts as pouring out water or burning incense are performed, and that they are wholly inexplicable and meaningless to him.

Nor will they confess that the real inspiration to perform such rites is the fact of their predecessors having handed them down as sacred acts of devotion, the meaning of which has been entirely forgotten during the process of transmission from antiquity. Instead of this they simply pretend that the significance of such acts is obvious. Stripped of the glamour which religious emotion and sophistry have woven around them, such pretended explanations become transparent subterfuges, none the less real because the apologists are quite innocent of any conscious intention to deceive either themselves or their disciples. It should be sufficient for them that such ritual acts have been handed down by tradition as right and proper things to do. But in response to the instinctive impulse of all human beings, the mind seeks for reasons in justification of actions of which the real inspiration is unknown.

It is a common fallacy to suppose that men's actions are inspired mainly by reason. The most elementary investigation of the psychology of everyday life is sufficient to reveal the truth that man is not, as a rule, the pre-eminently rational creature he is commonly supposed to be.[1] He is impelled to most of his acts by his instincts, the circumstances of his personal experience, and the conventions of the society in which he has grown up. But once he has acted or decided upon a course of procedure he is ready with excuses in explanation and attempted justification of his motives. In most cases these are not the real reasons, for few human beings attempt to analyse their motives or in fact are competent without help to understand their own feelings and the real significance of their actions. There is implanted in man the instinct to interpret for his own satisfaction his feelings and sensations, i.e. the meaning of his experience. But of necessity this is mostly of the nature of rationalizing, i.e. providing satisfying interpretations of thoughts and decisions the real meaning of which is hidden.

[1] On this subject see Elliot Smith and Pear, "Shell Shock and its Lessons, "Manchester University Press, 1917, p. 59.

Now it must be patent that the nature of this process of rationalization will depend largely upon the mental make-up of the individual - of the body of knowledge and traditions with which his mind has be- me stored in the course of his personal experience. The influences which he has been exposed, daily and hourly, from the time of his birth onward, provide the specific determinants of most of his beliefs nd views. Consciously and unconsciously he imbibes certain definite 'deas, not merely of religion, morals, and politics, but of what is the correct and what is the incorrect attitude to assume in most of the circumstances of his daily life.

[1] An interesting discussion of this matter by the late Professor William James will be found in his "Principles of Psychology, "Vol. 1, pp. 261 et seq.

These form the staple currency of his beliefs and his conversation. Reason plays a surprisingly small part in this process, for most human beings acquire from their fellows the traditions of their society which relieves them of the necessity of undue thought. The very words in which the accumulated traditions of his community are conveyed to each individual are themselves charged with the complex symbolism that has slowly developed during the ages, and tinges the whole of his thoughts with their subtle and, to most men, vaguely appreciated shades of meaning.1 During this process of acquiring the fruits of his community's beliefs and experiences every individual accepts without question a vast number of apparently ample customs and ideas. He is apt to regard them as obvious, and to assume that reason led him to accept them or be guided by them, although when the specific question is put to him he is unable to give their real history.

Before leaving these general considerations [2] I want to emphasize certain elementary facts of psychology which are often ignored by those who investigate the early history of civilization.

For a fuller discussion of certain phases of this matter see my address

on "Primitive Man, "in the Proceedings of the British Academv, 1917, especially pp. 23-50.First, the multitude and the complexity of the circumstances that are necessary to lead men to make even the simplest invention render the concatenation of all of these conditions wholly independently on a second occasion in the highest degree improbable. Until very definite and conclusive evidence is forthcoming in any individual case it can safely be assumed that no ethnologically significant innovation in customs or beliefs has ever been made twice.

Those critics who have recently attempted to dispose of this claim by referring to the work of the Patent Office thereby display a singular lack of appreciation of the real point at issue. For the ethnological problem is concerned with different populations who are assumed not to share any common heritage of acquired knowledge, nor to have had any contact, direct or indirect, the one with the other. But the inventors who resort to the Patent Office are all of them persons sup- plied with information from the storehouse of our common civilization and the inventions which they seek to protect from imitation by others are merely developments of the heritage of all civilized peoples. Even when similar inventions are made apparently independently under such circumstances, in most cases they can be explained by the fact that two investigators have followed up a line of advance which has been determined by the development of the common body of knowledge.

This general discussion suggests another factor in the working of the human mind.

When certain vital needs or the force of circumstances compel a man to embark upon a certain train of reasoning or invention the results to which his investigations lead depend upon a great many circumstances. Obviously the range of his knowledge and experience and the general ideas he has acquired from his fellows will play a large part in shaping his inferences. It is quite certain that even in the simplest problem of primitive physics or biology his attention will be directed only to some of, and not all, the factors involved, and that the limitations of his knowledge will permit him to form a wholly inadequate conception even of the few factors that have obtruded themselves upon his attention. But he may frame a working hypothesis in explanation of the factors he had appreciated, which may seem perfectly exhaustive and final, as well as logical and rational to him, but to those who come after him, with a wider knowledge of the properties of matter and the nature of living beings, and a wholly different attitude towards such problems, the primitive man's solution may seem merely a ludicrous travesty.

But once a tentative explanation of one group of phenomena has been made it is the .method of science no less than the common tendency of the human mind to buttress this theory with analogies and fancied homologies. In other words the isolated facts are built up into a generalisation. It is important to remember that in most cases this mental process begins very early; so that the analogies play a very obtrusive part in the building up of theories.

As a rule a multitude of such influences play a part consciously or unconsciously in shaping v belief. Hence the historian is faced with the difficulty, often insuperable, of ascertaining (among scores of factors that de finitely played some part in the building up of a great generalization) the real foundation upon which the vast edifice has been erected. 1 refer to these elementary matters here for two reasons. First, because they are so often overlooked by ethnologists; and secondly, because in these pages I shall have to discuss a series of historical events in which a bewildering number of factors played their part. In sifting out a certain number of them, I want to make it clear that 1 do not pretend to have discovered more than a small minority of the most conspicuous threads in the complex texture of the fabric of early human thought.

Another fact that emerges from these elementary psychological considerations is the vital necessity of guarding against the misunderstandings necessarily involved in the use of words. In the course of long ages the originally simple connotation of the words used to denote many of our ideas has become enormously enriched with a meaning which in some degree reflects the chequered history of the expression of human aspirations. Many writers who in discussing ancient peoples make use of such terms, for example, as "soul, " "religion, " and "gods, "without stripping them of the accretions of complex symbolism that have collected around them within more recent times, become involved in difficulty and misunderstanding.

For example, the use of the terms "soul "or "soul-substance "in much of the literature relating to early or relatively primitive people is fruitful of misunderstanding. For it is quite clear from the context that in many cases such people meant to imply nothing more than "life "or "vital principle, "the absence of which from the body for any prolonged period means death. But to translate such a word simply as "life "is inadequate because all of these people had some theoretical views as to its identity with the "breath "or to its being in the nature of a material substance or essence. It is naturally impossible to find any one word or phrase in our own language to express the exact idea, for among every people there are varying shades of meaning which cannot adequately express the symbolism distinctive of each place and society. To meet this insuperable difficulty perhaps the term "vital essence "is open to least objection.

In my last Rylands lecture 1 I sketched in rough outline a tentative explanation of the world-wide dispersal of the elements of the civilization that is now the heritage of the world at large, and referred to the part played by Ancient Egypt in the development of certain arts, customs, and beliefs. On the present occasion I propose to examine certain aspects of this process of development in greater detail, and to study the far-reaching influence exerted by the Egyptian practice of mummification, and the ideas that were suggested by it, in starting new trains of thought, in stimulating the invention of arts and crafts that were unknown before then, and in shaping the complex body of customs and beliefs that were the outcome of these potent intellectual ferments.

1 "The Influence of Ancient Egyptian Civilization in the East and in America, "The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, Jan.-March, 1916.

In speaking of the relationship of the practice of mummification to the development of civilization, however, I have in mind not merely the influence it exerted upon the moulding of culture, but also the part played by the trend of philosophy in the world at large in determining the Egyptian's conceptions of the wider significance of embalming, and the reaction of these effects upon the current doctrines of the meaning of natural phenomena.

No doubt it will be asked at the outset, what possible connexion can there be between the practice of so fantastic and gruesome an art as the embalming of the dead and the building up of civilization ? Is it conceivable that the course of the development of the arts and crafts, the customs and beliefs, and the social and political organizations; in fact any of the essential elements of civilization has been deflected a hair's breadth to the right or left as the outcome, directly or in directly, of such a practice?

In previous essays and lectures 2 I have indicated how intimately this custom was related, not merely to the invention of the arts and crafts of the carpenter and stonemason and all that is implied in the building up of what Professor Lethaby has called the "matrix of civilization, " but also to the shaping of religious beliefs and ritual practices, which developed in association with the evolution of the temple and the conception of a material resurrection.

2 "The Migrations of Early Culture, "1915, Manchester University Press : "The Evolution of the Rock-cut Tomb and the Dolmen, "Essays and Studies Presented by William Ridgeway, Cambridge, 1913, p. 493 : "Oriental Tombs and Temples, "Journal of the Manchester Egyptian and Oriental Society, 1914-1915, p. 55.

I have also suggested the far- reaching significance of an indirect influence of the practice of mummification in the history of civilization. It was mainly responsible for prompting the earliest great maritime expeditions of which the history has been preserved.1 For many centuries the quest of resins and balsams for embalming and for use in temple ritual, and wood for coffin-making, continued to provide the chief motives which induced the Egyptians to undertake sea-trafficking in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. The knowledge and experience thus acquired ultimately made it possible for the Egyptians and their pupils to push their adventures further afield. It is impossible adequately to estimate the vastness of the influence of such intercourse, not merely in spreading abroad throughout the world the germs of our common civilization, but also, by bringing into close contact peoples of varied histories and traditions, in stimulating progress. Even if the practice of mummification had exerted no other noteworthy effect in the history of the world, this fact alone would have given it a pre-eminent place.

Another aspect of the influence of mummification I have already discussed, and do not intend to consider further in this lecture. I refer to the manifold ways in which it affected the history of medicine and pharmacy. By accustoming the Egyptians, through thirty centuries, to the idea of cutting the human corpse, it made it possible for Greek physicians of the Ptolemaic and later ages to initiate in Alexandria the systematic dissection of the human body which popular prejudice forbade elsewhere, and especially in Greece itself. Upon this foundation the knowledge of anatomy and the science of medicine has been built up.' "But in many other ways the practice of mummification exerted far-reaching effects, directly and indirectly, upon the development of medical and pharmaceutical knowledge and methods.3

1 "Ships as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture, "Manchester University Press, 1917, p. 37.

2 Egyptian Mummies, "Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. I Part HI, July, 1914, p. 189.

3 Such, for example, as its influence in the acquisition of the means of preserving the tissues of the body, which has played so large a part in the development of the sciences of anatomy, pathology, and in fact biology in general. The practice of mummification was largely responsible for the attainment of a knowledge of the properties of many drugs and especially of those which restrain putrefactive changes. But it was not merely in the acquisition of a knowledge of material facts that mummification exerted its influence. The humoral theory of pathology and medicine, which prevailed for so many centuries and the effects of which are embalmed for all time in our common speech, was closely related in its inception to the ideas which 1 shall discuss in these pages. The Egyptians themselves did not profit to any appreciable extent from the remarkable opportunities which their practice of embalming provided for studying human anatomy. The sanctity of these ritual acts was fatal to the employment of such opportunities to gain know ledge. Nor was the attitude of mind of the Egyptians such as to permit the acquisition of a real appreciation of the structure of the body.

There is then this prima-facie evidence that the Egyptian practice of mummification was closely related to the development of architecture, maritime trafficking, and medicine. But what I am chiefly concerned with in the present lecture is the discussion of the much vaster part it played in shaping the innermost beliefs of mankind and directing the course of the religious aspirations and the scientific opinions, not merely of the Egyptians themselves, but also of the world at large, for many centuries afterward.

It had a profound influence upon the history of human thought. The vague and ill-defined ideas of physiology and psychology, which had probably been developing since Aurignacian times1 in Europe, were suddenly crystallized into a coherent structure and definite form by the musings of the Egyptian embalmer. But at the same time, if the new philosophy did not find expression in the invention of the first deities, it gave them a much more concrete form than they had previously presented, and played a large part in the establishment of the foundations upon which all religious ritual was subsequently built up, and in the initiation of a priesthood to administer the rites which were suggested by the practice of mummification.

THE BEGINNING OF STONE-WORKING.

During the last few years I have repeatedly had occasion to point out the fundamental fallacy underlying much of the modern speculation in ethnology, and I have no intention of repeating these strictures here.2 But it is a significant fact that, when one leaves the writings of professed ethnologists and turns to the histories of their special subjects written by scholars in kindred fields of investigation, views such as I have been setting forth will often be found to be accepted without uestion or comment as the obvious truth.

1 See my address, "Primitive Man, "Proc. Brit. Academy, 1917.

2 See, however, op. cit. supra; also "The Origin of the Pre-Columbian Civilization of America, "Science, N.S., Vol. XLV, No. 1158, pp. 241- 246, 9 March, 1917.

There is an excellent little book entitled "Architecture, " written by professor W. R. Lethaby for the Home University Library, that affords an admirable illustration of this interesting fact. I refer to this particular work because it gives lucid expression to some of the ideas that I wish to submit for consideration. "Two arts have changed the surface of the world, Agriculture and Architecture "(p. 1 ). "To a large degree architecture "[which he defines as "the matrix of civilization "] "is an Egyptian art "(p. 66) : for in Egypt "we shall best find the origins of architecture as a whole "(p. 21 ).

Nevertheless Professor Lethaby bows the knee to current tradition when he makes the wholly unwarranted assumption that Egypt probably learnt its art from Babylonia. He puts forward this remarkable claim in spite of his frank confession that "little or nothing is known of a primitive age in Mesopotamia. At a remote time the art of Babylonia was that of a civilized people. As has been said, there is a great similarity between this art and that of dynastic times in Egypt. Yet it appears that Egypt borrowed of Asia, rather than the reverse. "[He gives no reasons for this opinion, for which there is no evidence, except possibly the invention of bricks for building.] "If the origins of art in Babylonia were as fully known as those in Egypt, the story of architecture might have to begin in Asia instead of Egypt " (p. 67).

But later on he speaks in a more convincing manner of the known facts when he says (p. 82):

When Greece entered on her period of high-strung life the time of first invention in the arts was owed to the heroes of Craft, like Tubal Cain and Daedalus, necessarily belong to the infancy of culture. The phenomenon of Egypt could not occur again; the mission of Greece was rather to settle down to a task of gathering, interpreting, and bringing to perfection Egypt's gifts. The arts of civilization were never developed in water tight compartments, as is shown by the uniformity of custom over the modern world. Further, if any new nation enters into the circle of culture it seems that, like Japan, it must ' borrow the capital '. The art of Greece could hardly have been more self-originated than is the science of Japan. Ideas of the temple and of the fortified town must have spread from the East, the square-roomed house, columnar orders, fine masonry, were all Egyptian.

Elsewhere I have pointed out that it was the importance which the Egyptian came to attach to the preservation of the dead and to the making of adequate provision for the deceased's welfare that gradually led to the aggrandisement of the tomb. In course of time this impelled him to cut into the rock,1 and, later still, suggested the substitution of stone for brick in erecting the chapel of offerings above ground. The Egyptian burial customs were thus intimately related to the conceptions that grew up with the invention of embalming. The evidence in confirmation of this is so precise that every one who conscientiously examines it must be forced to the conclusion that man did not instinctively select stone as a suitable material with which to erect temples and houses, and forthwith begin to quarry and shape it for such purposes.

1 For the earliest evidence of the cutting of stone for architectural purposes, see my statement in the Report of the British Association for 1914, p. 212.

There was an intimate connexion between the first use of stone for building and the practice of mummification. It was probably for this reason, and not from any abstract sense of "wonder at the magic of art, "as Professor Lethaby claims, that "ideas of sacredness, of ritual rightness, of magic stability and correspondence with the universe, and of perfection of form and proportion "came to be associated with stone buildings.

At first stone was used only for such sacred purposes, and the pharaoh alone was entitled to use it for his palaces, in virtue of the fact that he was divine, the son and incarnation on earth of the sun- god. It was only when these Egyptian practices were transplanted to other countries, where these restrictions did not obtain, that the rigid wall of convention was broken down.

Even in Rome until well into the Christian era "the largest domes tic and civil buildings were of plastered brick ". "Wrought masonry seems to have been demanded only for the great monuments, triumphal arches, theatres, temples and above all for the Coliseum. "(Lethaby, op. cit. p. 120).

Nevertheless Rome was mainly responsible for breaking down the hieratic tradition which forbade the use of stone for civil purposes. "In Roman architecture the engineering element became paramount. It was this which broke the moulds of tradition and recast construction into modern form, and made it free once more "(p. 130).

But Egypt was not only responsible for inaugurating the use of stone for building. For another forty centuries she continued to be the inventor of new devices in architecture. From time to time methods of building which developed in Egypt were adopted by her neighbours and spread far and wide. The shaft-tombs and mastabas of the Egyptian Pyramid Age were adopted in various localities in the region of the Eastern Mediterranean, especially in Crete, Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Southern Russia, and the North African Littoral, with certain modifications in each place, and in turn became the models which were roughly copied in later ages by the wandering dolmen-builders. The round tombs of Crete and Mycenae were clearly only local modifications of their square prototypes, the Egyptian Pyramids of the Middle Kingdom. "While this Ægean art gathered from, and perhaps gave to, Egypt, it passed on its ideals to the north and west of Europe, where the productions of the Bronze Age clearly show its influence " (Lethaby, p. 78) in the chambered mounds of the Iberian peninsula and Brittany, of New Grange in Ireland and of Macs Howe in the Orkneys. In the East the influence of these Ægean modifications may possibly be seen in the Indian stiipas and the dagabas of Ceylon, just as the stone stepped pyramids there reveal the effects of contact with the civilizations of Babylonia and Egypt.

Professor Lethaby sees the influence of Egypt in the orientation of Christian churches (p. 133), as well as in many of their structural de tails (p. 142); in the domed roofs, the iconography, the symbolism, and the decoration of Byzantine architecture (p. 138); and in Mohammedan buildings wherever they are found.

For it was not only the architecture of Greece, Rome, and Christendom that received its inspiration from Egypt, but that of Islam also. These buildings were not, like the religion itself, in the main Arabic in origin. "Primitive Arabian art itself is quite negligible. When the new strength of the followers of the Prophet was consolidated with great rapidity into a rich and powerful empire, it took over the arts and artists of the conquered lands, extending from North Africa to Persia "(p. 158); and it is known how this influence spread as far west as Spain and as far east as Indonesia. "The Pharos at Alexandria, the great lighthouse built about 280 B.C., almost appears to have been the parent of all high and isolated towers. , . . Even on the coast of Britain, at Dover, we had a Pharos which was in some degree an imitation of the Alexandrian one. "The Pharos at Boulogne, the round towers of Ravenna, and the imitations of it elsewhere in Europe, even as far as Ireland, are other examples of its influence. But in addition the Alexandrian Pharos had "as great an effect as the prototype of Eastern minarets as it had for Western towers "(p. 1 15).

For an account of the evidence relating to these monuments, with full bibliographical references, see Déchelette, "Manuel d'Archéologie pré historique Celtique et Gallo-Romaine, "T. 1, 1912, pp. 390 et sec. : also Sophus Meller, "Urgeschichte Europas, "1905, pp. 74 and 75; and Louis Siret, "Les Cassitérides et l'Empire Colonial des Phéniciens, " L'Anthropologie, T. 20, 1909, p. 313.

I have quoted so extensively from Professor Lethaby's brilliant little book to give this independent testimony of the vastness of the influence exerted by Egypt during a span of nearly forty centuries in creating and developing the "matrix of civilization ". Most of this wider dispersal abroad was effected by alien peoples, who transformed their gifts from Egypt before they handed on the composite product to some more distant peoples. But the fact remains that the great centre of original inspiration in architecture was Egypt.

The original incentive to the invention of this essentially Egyptian art was the desire to protect and secure the welfare of the dead. The importance attached to this aim was intimately associated with the development of the practice of mummification.

With this tangible and persistent evidence of the general scheme of spread of the arts of building I can now turn to the consideration of some of the other, more vital, manifestations of human thought and aspirations, which also, like the "matrix of civilization "itself, grew up in intimate association with the practice of embalming the dead.

I have already mentioned Professor Lethaby's reference to architecture and agriculture as the two arts that have changed the surface of the world. It is interesting to note that the influence of these two in gradients of civilization was diffused abroad throughout the world in intimate association the one with the other. In most parts of the world the use of stone for building and Egyptian methods of architecture made their first appearance along with the peculiarly distinctive form

I agriculture and irrigation so intimately associated with early Babylonia and Egypt.1

1 . ' W. J. Perry, "The Geographical Distribution of Terraced Cultivation and Irrigation, "Memoirs and Proc. Manch. Lit. and Phil. Soc. Vol. 60, 1916.

But agriculture also exerted a most profound influence in shaping the early Egyptian body of beliefs.

I shall now call attention to certain features of the earliest mummies, and then discuss how the ideas suggested by the practice of the art of embalming the dead were affected by the early theories of agriculture and the mutual influence they exerted one upon the other.

THE ORIGIN OF EMBALMING.

I have already explained how the increased importance that came to be attached to the corpse as the means of securing a continuance of existence led to the aggrandizement of the tomb. Special care was taken to protect the dead and this led to the invention of coffins, and to the making of a definite tomb, the size of which rapidly increased as more and more ample supplies of food and other offerings were made. But the very measures thus taken the more efficiently to protect and tend the dead defeated the primary object of all this care. For, when buried in such an elaborate tomb, the body no longer be came desiccated and preserved by the forces of nature, as so often happened when it was placed in a simple grave directly in the hot dry sand.

It is of fundamental importance in the argument set forth here to remember that these factors came into operation before the time of the First Dynasty. They were responsible for impelling the Proto-Egyptians not only to invent the wooden coffin, the stone sarcophagus, the rock-cut tomb, and to begin building in stone, but also to devise measures for the artificial preservation of the body.

But in addition to stimulating the development of the first real architecture and the art of mummification other equally far-reaching results in the region of ideas and beliefs grew out of these practices.

From the outset the Egyptian embalmer was clearly inspired by

two ideals :

(a) to preserve the actual tissues of the body with a minimum

disturbance of its superficial appearance; and

(b) to preserve a likeness of the deceased as he was in life. At

first it was naturally attempted to make this simulacrum of the

body if it were possible, or alternatively, when this ideal was

found to be unattainable, from its wrappings or by means of a

portrait statue. It was soon recognized that it was beyond the

powers of the early embalmer to succeed in mummifying the body

itself so as to retain a recognizable likeness to the man when

alive: although from time to time such attempts were repeatedly

made,1 until the period of the XXI Dynasty, when the

operator clearly was convinced that he had at last achieved what

his predecessors, for perhaps twenty-five centuries, had been

trying in vain to do.

EARLY MUMMIES

In the earliest known (Second Dynasty) examples of Egyptian attempts at mummification2 the corpse was swathed in a large series of bandages, which were moulded into shape to represent the form of the body. In a later (probably Fifth Dynasty) mummy, found in 1892 by Professor Flinders Pétrie at Medom, the superficial bandages had been impregnated with a resinous paste, which while still plastic was moulded into the form of the body, special care being bestowed upon the modelling of the face3 and the organs of reproduction, so as to leave no room for doubt as to the identity and the sex. Professor Junker has described4 an interesting series of variations of these practices. In two graves the bodies were covered with a layer of stucco plaster. First the corpse was covered with a fine linen cloth: then the plaster was put on, and modelled into the form of the body But in two other cases it was not the whole body that was covered with this layer of stucco, but only the head. Professor Junker claims that this was done "apparently because the head was regarded as the most important part, as the organs of taste, sight, smell, and hearing were contained in it ". But surely there was the additional and more obtrusive reason that the face affords the means of identifying the individual! For this modelling of the features was intended primarily as a restoration of the form of the body which had been altered, if not actually destroyed. In other cases, where no attempt was made to restore the features in such durable materials as resin or stucco, the linen-enveloped head was modelled, and a representation of the eyes painted upon it so as to enhance the life-like appearance of the face.

1 See my volume on "The Royal Mummies, "General Catalogue ol the Cairo Museum.

2 G. Elliot Smith, "The Earliest Evidence of Attempts at Mummification in Egypt, "Report British Association, 1912, p. 612: compare also J. Garstang, "Burial Customs of Ancient Egypt, "London, 1907, pp. 29 and 30. Professor Garstang did not recognize that mummification had been attempted.

3 G. Elliot Smith, "The History of Mummification in Egypt, "Pro Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow, 1910 : also "Egyptian Mummies, " journal of Egyptian Archeology, Vol. I, Part III, July, 1914, Plate

4 "Excavations of the Vienna Imperial Academy of Sciences at the Pyramids of Gizah, 1914, "Journal of 'Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. I, Oct. 1914, p. 250.

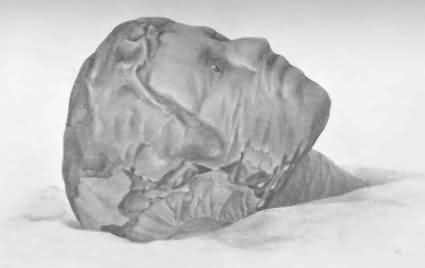

A MOULD TAKEN FROM A LIFE-MASK FOUND IN THE PYRAMID OF TETA BY MR. QUIBELL

These facts prove quite conclusively that the earliest attempts to reproduce the features of the deceased and so preserve his likeness, were made upon the wrapped mummy itself. Thus the mummy was intended to be the portrait as well as the actual bodily remains of the dead. In view of certain differences of opinion as to the original significance of the funerary ritual, which I shall have occasion to discuss later on, it is important to keep these facts clearly in mind.

About this time also the practice originated of making a life-size portrait statue of the dead man's head and placing it along with the actual body in the burial chamber. These "reserve heads, "as they have been called, were usually made of fine limestone, but Junker found one made of Nile mud.2

A discovery made by Mr. J. E. Quibell in the course of his excavations at Sakkara suggests that, as an outcome of these practices a new procedure may have been devised in the Pyramid Age - the making of a death-mask. For he discovered what may be the mask taken directly from the face of the Pharaoh Teta (Fig. 3).

Junker believes that there was an intimate relationship between the plaster-covered heads and the reserve-heads. They were both expressions of the same idea, to preserve a simulacrum of the deceased when his actual body had lost all recognizable likeness to him as he was when alive. The one method aimed at combining in the sanie object the actual body and the likeness; the other at making a more life-like portrait apart from the corpse, which could take the place of the latter when it decayed.

2 The great variety of experiments that were being made at the be ginning of the Pyramid Age bears ample testimony to the fact that the original inventors of these devices were actually at work in Lower Egypt st that time.

Junker states further that "it is no chance that the substitute- heads . . . entirely, or at any rate chiefly, are found in the tombs that have no statue-chamber and probably possessed no statues. The statues [of the whole body] certainly were made, at any rate partly, with the intention that they should take the place of the decaying body, although later the idea was modified. The placing of the substitute-head in [the burial chamber of] the mastaba therefore be came unnecessary at the moment when the complete figure of the dead [placed in a special hidden chamber, now commonly called the serdab} was introduced. "The ancient Egyptians themselves called the serdab fazpr-twt or "statue-house, "and the group of chambers, forming the tomb-chapel in the mastaba, was known to them as the "ka-house "1

FIG. 4.PORTRAIT STATUE OF AN EGYPTIAN LADY OF THE PYRAMID AGE

It is important to remember that, even when the custom of making a statue of the deceased became fully established, the original idea of restoring the form of the mummy itself or its wrappings was never abandoned. The attempts made in the XVIII, and XXI and XXII Dynasties to pack the body of the mummy itself and by artificial means give it a life-like appearance afford evidence of this. In the New Empire and in Roman times the wrapped mummy was sometimes modelled into the form of a statue. But throughout Egyptian history it was a not uncommon practice to provide a painted mask for the wrapped mummy, or in early Christian times simply a portrait of the deceased.

With this custom there also persisted a remembrance of its original significance. Professor Garstang records the fact that in the XII Dynasty,2 when a painted mask was placed upon the wrapped mummy, no statue or statuette was found in the tomb. The undertakers apparently realized that the mummyl which was provided with the life-like mask was therefore fulfilling the purposes for which statues were devised. So also in the New Empire the packing and model of the actual mummy so as to restore its life-like appearance were regarded as obviating the need for a statue.

1 Aylward M. Blackman, "The Ka-House and the Serdab, "Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. Ill, Part IV, Oct., 1916, p. 250. The word serdab is merely the Arabic word used by the native workmen, which has been adopted and converted into a technical term by European archaeologists.

I must now return to the further consideration of the Old Kingdom statues. All these varied experiments were inspired by the same desire, to preserve the likeness of the deceased. But when the sculptors attained their object, and created those marvellous life-like portraits, which must ever remain marvels of technical skill and artistic feeling (Fig. 4), the old ideas that surged through the minds of the Pre-dynastic Egyptians, as they contemplated the desiccated remains of the dead, were strongly reinforced. The earlier people's thoughts were turned more specifically than heretofore to the contemplation of the nature of life and death by seeing the bodies of their dead pre served whole and incorruptible; and, if their actions can be regarded as an expression of their ideas, they began to wonder what was lacking in these physically complete bodies to prevent them from feeling and acting like living beings.

Such must have been the results of their puzzled contemplation of the great problems of life and death. Otherwise the impulse to make more certain the preservation of the body by the invention of mummification and to retain a life-like representation of the deceased by means of a sculptured statue remains inexplicable. But when the corpse had been rendered incorruptible and the deceased's portrait had been fashioned with realistic perfection the old ideas would recur with renewed strength. The belief then took more definite shape that if the missing elements of vitality could be restored to the statue, it might become animated and the dead man would live again in his vitalized statue. This prompted a more intense and searching investigation of the problems concerning the nature of the elements of vitality of which the corpse was deprived at the time of death. Out of these inquiries in course of time a highly complex system of philosophy developed.2

' It is a remarkable fact that Professor Garstang, who brought to light perhaps the best, and certainly the best-preserved, collection of Middle Kingdom mummies ever discovered, failed to recognize the fact that they had really been embalmed (op. at. p. 171).

2 The reader who wishes for fuller information as to the reality of these beliefs and how seriously they were held will find them still in active operation in China. An admirable account of Chinese philosophy will be found in De Groot's "Religious System of China, "especially Vol. IV, Book II. It represents the fully developed (New Empire) system of Egyptian belief modified in various ways by Babylonian, Indian and Central Asiatic influences, as well as by accretions developed locally in China.

But in the earlier times with which I am now concerned it formed a practical expression in certain ritual procedures, invented to convey t0 the statue the breath of life, the vitalising fluids, and the odour and sweat of the living body. The seat of knowledge and of feeling believed to be retained in the body when the heart was left in situ: that the only thing needed to awaken consciousness, and make it possible for the dead man to take heed of his friends and to act voluntarily, was to present offerings of blood to stimulate the physiological functions of the heart. But the element of vitality which left the body at death had to be restored to the statue, which represented the deceased in the Ka-house.1

In my earlier attempts2 to interpret these problems, I adopted the view that the making of portrait statues was the direct outcome of the practice of mummification. But Dr. Alan Gardiner, whose intimate knowledge of the early literature enables him to look at such problems from the Egyptian's own point of view, has suggested a modification of this interpretation. Instead of regarding the custom of making statues as an outcome of the practice of mummification, he thinks that the two customs developed simultaneously, in response to the twofold desire to preserve both the actual body and a representation of the features of the dead. But I think this suggestion does not give adequate recognition to the fact that the earliest at tempts at funerary portraiture were made upon the wrappings of the actual mummies.3

This fact and the evidence which I have already from Junker make it quite clear that from the beginning the palmer's aim was to preserve the body and to convert the mummy into a simulacrum of the deceased. When he realized that technical skill was not adequate to enable him to accomplish this aim, he fell back upon the device of making a more perfect and realistic portrait statue apart from the mummy. But, as I have already pointed out, he never completely renounced his ambition of transforming the mummy itself; and in the time of the New Empire he actually attained the result which he had kept in view for nearly twenty centuries.

1 A. M. Blackman, "The Ka-House and the Serdab, "The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. Ill, Part IV, Oct., 1916, p. 250.

2 "Migrations of Early Culture, "p. 37.

Dr. Alan Gardiner (Davies and Gardiner, "The Tomb of Amenemhét, "1915, p. 83, footnote) has, I think, overlooked certain statements in my writings and underestimated the antiquity of the embalmer's art; for he attributes to me the opinion that "mummification was a custom of relatively late growth ".

The presence in China of the characteristically Egyptian beliefs concerning the animation of statues (de Groot, op. cit. pp. 339-356), whereas the practice of mummification, though not wholly absent, is not obtrusive might perhaps be interpreted by some scholars as evidence in favour of the development of the custom of making statues independently of mummification. But such an inference is untenable. Not only is it the fact that in most parts of the world the practices of making statues and mummifying the dead are found in association the one with the other, but also in China the essential beliefs concerning the dead are based upon the supposition that the body is fully preserved (see de Groot, chap. XV.). It is quite evident that the Chinese customs have been derived directly or indirectly from some people who mummified their dead as a regular practice. There can be no doubt that the ultimate source of their inspiration to do these things was Egypt.

I need mention only one of many identical peculiarities that makes this quite certain. De Groot says it is "strange to see Chinese fancy depict the souls of the viscera as distinct individuals with animal forms "(p. 71). The same custom prevailed in Egypt, where the "souls " or protective deities were first given animal forms in the Nineteenth Dynasty (Reisner).

In these remarks I have been referring only to funerary portrait statues. Centuries before the attempt was made to fashion them modellers had been making of clay and stone representations of cattle and human beings, which have been found not only in Predynastic graves in Egypt but also in so-called "Upper Palaeolithic " deposits in Europe.

But the fashioning of realistic and life-size human portrait-statues for funerary purposes was a new art, which gradually developed in the way I have tried to depict. No doubt the modellers made use of the skill they had acquired in the practice of the older art of rough impressionism.

Once the statue was made a stone-house (the serdab) was provided for it above ground.1. As the dolmen is a crude copy of the serdab it can be claimed as one of the ultimate results of the practice of mummification. It is clear that the conception of the possibility of a life beyond the grave assumed a more concrete form when it was realized that the body itself could be rendered incorruptible and distinctive traits could be kept alive by means of a portrait statue. There are reasons for supposing that primitive man did not realize or contemplate the possibility of his own existence coming to an end.1

Even when he witnessed the death of his fellows he does not appear to have appreciated the fact that it was really the end of life and not merely a kind of sleep from which the dead might awake. But if the corpse were destroyed or underwent a process of natural disintegration the fact was brought home to him that death had occurred.

If these considerations, which early Egyptian literature seems to suggest, be borne in mind, the view that the preservation of the body from corruption implied a continuation of existence becomes intelligible. At first the subterranean chambers in which the actual body was housed were developed into a many-roomed house for the deceased, complete in every detail.3 But when the statue took over the function of representing the deceased, a dwelling was provided for it above ground. This developed into the temple where the relatives and friends of the dead came and made the offerings of food which were regarded as essential for the maintenance of existence.

1 The Arabic word conveys the idea of being "hidden underground, " because the house is exposed by excavation.

See Alan H. Gardiner, "Life and Death (Egyptian), "Hastings' Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics.

2 See the quotation from Mr. Quibell's account in my statement in the Report of the British Association for 1914, p. 215.

3 Mr. Blackman here quotes the actual word in hieroglyphics and adds the translation "god's fluid "and the following explanation in a footnote : "The Nile was supposed to be the fluid which issued from Osiris. The expression in the Pyramid texts may refer to this belief ” the dead "[in the Pyramid Age it would have been more accurate if he had said the dead king, in whose Pyramid the inscriptions were found] "being usually identified with Osirisâ since the water used in the libations was Nile water. "

The evolution of the temple was thus the direct outcome of the ideas that grew up in connexion with the preservation of the dead. For at first it was nothing more than the dwelling place of the re animated dead. But when, for reasons which I shall explain later (see p. 30), the dead king became deified, his temple of offerings became the building where food and drink were presented to the god, not merely to maintain his existence, but also to restore his consciousness, and so afford an opportunity for his successor, the actual king, to consult him and obtain his advice and help. The presentation of offerings and the ritual procedures for animating and restoring consciousness to the dead king were at first directed solely to these ends. But in course of time, as their original purpose became obscured, these services in the temple altered in character, and their meaning became turned into acts of homage and worship, and of prayer and plication, and in much later times, acquired an ethical and moral significance that was wholly absent from the original conception of the temple services. The earliest idea of the temple as a place of offering has not been lost sight of. Even in our times the offertory still finds a place in temple services.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF LIBATIONS.

The central idea of this lecture was suggested by Mr. Aylward M. Blackman's important discovery of the actual meaning of incense and libations to the Egyptians themselves.1 The earliest body of literature preserved from any of the peoples of antiquity is comprised in the texts inscribed in the subterranean chambers of the Sakkara Pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. These documents, written forty-five centuries ago, were first brought to light in modern times in 1880-81; and since the late Sir Gaston Maspero published the first translation of them, many scholars have helped in the task of elucidating their meaning. But it remained for Blackman to discover the ex planation they give of the origin and significance of the act of pouring out libations. "The general meaning of these passages is quite clear. The corpse of the deceased is dry and shrivelled. To revivify it the vital fluids that have exuded from it [in the process of mummification] must be restored, for not till then will life return and the heart beat again. This, so the texts show us, was believed to be accomplished by offering libations to the accompaniment of incantations "(pp. cit. p. 70).

In the first three passages quoted by Blackman from the Pyramid Texts "the libations are said to be the actual fluids that have issued from the corpse ". In the next four quotations "a different notion is introduced. It is not the deceased's own exudations that are to revive his shrunken frame but those of a divine body, the [god's fluid] ' that came from the corpse of Osiris himself, the juices that dissolved from his decaying flesh, which are communicated to the dead sacrament- wise under the form of these libations. "

1 "The Significance of Incense and Libations in Funerary and Temple Ritual, "Sprache und Altertumskunde, Bd. 50, 1912, p. 69.

This dragging-in of Osiris is especially significant. For the analogy of the life-giving power of water that is specially associated with Osiris played a dominant part in suggesting the ritual of libations. Just as water, when applied to the apparently dead seed, makes it germinate and come to life, so libations can reanimate the corpse. These general biological theories of the potency of water were current at the time and, as I shall explain later (see p. 28), had possibly received specific application to man long before the idea of libations developed. For, in the development of the cult of Osiris l the general fertilizing value when applied to the soil found specific exemplification in the potency of the seminal fluid to fertilize human beings. Malinowski pointed out that certain Papuan people, who are ignorant of the fact that women are fertilized by sexual connexion, believe that they be rendered pregnant by rain falling upon them (op. cit. infra).

1 The voluminous literature relating to Osiris will be found summarized in the latest edition of "The. Golden Bough "by Sir James Frazer. But in referring the reader to this remarkable, compilation of evidence, it is necessary to call particular attention to the fact that Sir James Frazer's interpretation is permeated with speculations based upon the modern ethnological dogma of independent evolution of similar customs and beliefs without cultural contact between the different localities where such similarities make their appearance.

The complexities of the motives that inspire and direct human activities are entirely fatal to such speculations, as I have attempted to indicate, (see above, p. 195). But apart from this general warning, there are other objections to Sir James Frazer's theories. In his illuminating article upon Osiris and Horus, Dr. Alan Gardiner (in a criticism of Sir James Frazer's "The Golden Bough : Adonis, Attis, Osiris; Studies in the History of Oriental Religion, "Journal of Egyptian Archeology, Vol. II, 1915, p. 122) insists upon the crucial fact that Osiris was primarily a king, and that "it is always as a dead king, " "the role of the living king being invariably played by Horus, his son and heir ".

He states further : "What Egyptologists wish to know about Osiris beyond anything else is how and by what means he became, associated with the processes of vegetable life ". An examination of the. literature relating to Osiris and the. large series of homologous deities in other countries (which exhibit prima fade evidence of a common origin) suggests the idea that the king who first introduced the practice of systematic irrigation there by laid the foundation of his reputation as a beneficent reformer. When, for reasons which I shall discuss later on (see p. 220), the. dead king be came deified, his fame as the controller of water and the fertilization of the earth became apotheosized also. I venture to put forward this suggestion only because none, of the alternative hypotheses have, been propounded seem to be in accordance with, or to offer an adequate explanation of, the body of known facts concerning Osiris.