Chapter XV: The Grææ and the Gorgons, Perseus and Medusa, Atlas-Andromeda

The Grææ And Gorgons

Pyxis Ática from the National Archaeological Museum of Athens showing Perseus stealing the eye from three Grææ

The Grææ were three sisters who lived in the Western extreme of the ocean. Their names were Deino, Pephredo, and Enyo, which mean "alarm," "dread," and "horror." They were the daughters of Phorkys and Keto. The Graea shared one eye and one tooth among one another and were believed to be hideous looking creatures.

They dwelt near the entrance to the Underworld, and were the gaurdians of the Gorgons. They protected the nymphs, who protected Hades' invisible helmet and a pair of winged sandals belonging to Hermes. They also oversaw the safety of the shield of Athena.

THE Grææ were three sisters who were gray–haired from their birth, whence their name. The Gorgons were monstrous females with huge teeth like those of swine, brazen claws, and snaky hair. None of these beings make much figure in mythology except Medusa, the Gorgon, whose story we shall next advert to.

We mention them chiefly to introduce an ingenious theory of some modern writers, namely, that the Gorgons and Grææ were only personifications of the terrors of the sea, the former denoting the strong billows of the wide open main, and the latter the white–crested waves that dash against the rocks of the coast. Their names in Greek signify the above epithets.

PERSEUS AND MEDUSA.

Perseus was the son of Jupiter and Danae.

His grandfather Acrisius, alarmed by an oracle which had told him that his daughter’s child would be the instrument of his death, caused the mother and child to be shut up in a chest and set adrift on the sea.

The chest floated towards Seriphus, where it was found by a fisherman who conveyed the mother and infant to Polydectes, the king of the country, by whom they were treated with kindness. When Perseus was grown up Polydectes sent him to attempt the conquest of Medusa, a terrible monster who had laid waste the country. She was once a beautiful maiden whose hair was her chief glory but as she dared to vie in beauty with Minerva, the goddess deprived her of her charms and changed her beautiful ringlets into hissing serpents.

She became a cruel monster of so frightful an aspect that no living thing could behold her without being turned into stone. All around the cavern where she dwelt might be seen the stony figures of men and animals which had chanced to catch a glimpse of her and had been petrified with the sight.

Perseus, favoured by Minerva and Mercury, the former of whom lent him her shield and the latter his winged shoes, approached Medusa while she slept and taking care not to look directly at her, but guided by her image reflected in the bright shield which he bore, he cut off her head and gave it to Minerva, who fixed it in the middle of her AEgis.

Milton, in his “Comus,” thus alludes to the AEgis:

“What thus snaky-headed Gorgon-shield

That wise Minerva wore, unconquered virgin,

Wherewith she freezed her foes to congealed stone,

But rigid looks of chaste austerity,

And noble grace that dashed brute violence

With sudden adoration and blank awe!”

[See: Comus by John Milton]

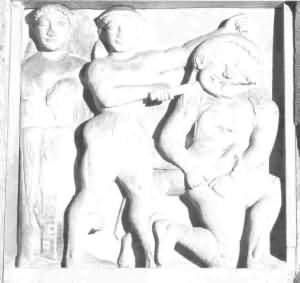

Medusa the Gorgon about to met her fate at the hands of

Perseus, with Athena standing behind him.

An architectual sculpture from the ancient temple at Selinunte,

Sicily

Armstrong, the poet of the “Art of Preserving Health,” thus describes the effect of frost upon the waters:

“Now blows the surly North and chills throughout

The stiffening regions, while by stronger charms

Than Circe e’er or fell Medea brewed,

Each brook that wont to prattle to its banks

Lies all bestilled and wedged betwixt its banks,

Nor moves the withered reeds...

The surges baited by the fierce North-east,

Tossing with fretful spleen their angry heads,

E’en in the foam of all their madness struck

To monumental ice.

. . . . . . . .

Such execution,

So stern, so sudden, wrought the grisly aspect

Of terrible Medusa,

When wandering through the woods she turned to stone

Their savage tenants; just as the foaming Lion

Sprang furious on his prey, her speedier power

Outran his haste,

And fixed in that fierce attitude he stands

Like Rage in marble!”- Imitations of Shakespeare.

[See: Art of Preserving Health] [The Quest Of Medusa's Head]

PERSEUS AND ATLAS.

Atlas p. 141 1908 Edition

After the slaughter of Medusa, Perseus, bearing with him the head of the Gorgon, flew far and wide, over land and sea. As night came on, he reached the western limit of the earth, where the sun goes down. Here he would gladly have rested till morning.

It was the realm of King Atlas, whose bulk surpassed that of all other men. He was rich in flocks and herds and had no neighbour or rival to dispute his state. But his chief pride was in his gardens whose fruit was of gold, hanging from golden branches, half hid with golden leaves. Perseus said to him,

“I come as a guest. If you honour illustrious descent, I claim Jupiter for my father; if mighty deeds, I plead the conquest of the Gorgon. I seek rest and food.”

But Atlas remembered that an ancient prophecy had warned him that a son of Jove should one day rob him of His golden apples. So he answered,

“Begone! or neither your false claims of glory nor parentage shall protect you;”

and he attempted to thrust him out. Perseus, finding the giant too strong for him, said,

“Since you value my friendship so little, deign to accept a present;”

and turning his face away, he held up the Gorgon’s head.

Atlas, with all his bulk, was changed into stone. His beard and hair became forests, his arms and shoulders cliffs, his head a summit, and his bones rocks. Each part increased in bulk till be became a mountain, and (such was the pleasure of the gods) heaven with all its stars rests upon his shoulders.

THE SEA–MONSTER.

Perseus, continuing his flight, arrived at the country of the AEthiopians, of which Cepheus was king. Cassiopeia his queen, proud of her beauty, had dared to compare herself to the Sea–nymphs, which roused their indignation to such a degree that they sent a prodigious sea–monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to expose his daughter Andromeda to be devoured by the monster.

As Perseus looked down from his aerial height he beheld the virgin chained to a rock, and waiting the approach of the serpent. She was so pale and motionless that if it had not been for her flowing tears and her hair that moved in the breeze, he would have taken her for a marble statue. He was so startled at the sight that he almost forgot to wave his wings.

As he hovered over her he said,

“O virgin, undeserving of those chains, but rather of such as bind fond lovers together, tell me, I beseech you, your name, and the name of your country, and why you are thus bound.”

At first she was silent from modesty, and, if she could, would have hid her face with her hands; but when he repeated his questions, for fear she might be thought guilty of some fault which she dared not tell, she disclosed her name And that of her country, and her mother’s pride of beauty.

Before she had done speaking, a sound was heard off upon the water, and the sea–monster appeared, with his head raised above the surface, cleaving the waves with his broad breast. The virgin shrieked, the father and mother who had now arrived at the scene, wretched both, but the mother more justly so, stood by, not able to afford protection, but only to pour forth lamentations and to embrace the victim. Then spoke Perseus;

“There will be time enough for tears; this hour is all we have for rescue. My rank as the son of Jove and my renown as the slayer of the Gorgon might make me acceptable as a suitor; but I will try to win her by services rendered, if the gods will only be propitious. If she be rescued by my valour, I demand that she be my reward.”

The parents consent (how could they hesitate?) and promise a royal dowry with her.

And now the monster was within the range of a stone thrown by a skilful slinger, when with a sudden bound the youth soared into the air. As an eagle, when from his lofty flight he sees a serpent basking in the sun, pounces upon him and seizes him by the neck to prevent him from turning his head round and using his fangs, so the youth darted down upon the back of the monster and plunged his sword into its shoulder.

Irritated by the wound, the monster raised himself into the air, then plunged into the depth; then, like a wild boar surrounded by a pack of barking dogs, turned swiftly from side to side, while the youth eluded its attacks by means of his wings. Wherever he can find a passage for his sword between the scales he makes a wound, piercing now the side, now the flank, as it slopes towards the tail.

The brute spouts from his nostrils water mixed with blood. The wings of the hero are wet with it, and he dares no longer trust to them. Alighting on a rock which rose above the waves, and holding on by a projecting fragment, as the monster floated near he gave him a death stroke. The people who had gathered on the shore shouted so that the hills reechoed with the sound.

The parents, transported with joy, embraced their future son–in–law, calling him their deliverer and the saviour of their house, and the virgin, both cause and reward of the contest, descended from the rock.

Marble relief of Perseus and Andromeda,

Capitoline Museum, Rome.

Cassiopeia was an AEthiopian, and consequently, in spite of her boasted beauty, black; at least so Milton seems to have thought, who alludes to this story in his “Penseroso,” where he addresses Melancholy as the

“...goddess, sage and holy,

Whose saintly visage is too bright

To hit the sense of human sight,

And, therefore, to our weaker view,

O’erlaid with black, staid Wisdom’s hue.

Black, but such as in esteem

Prince Memnon’s sister might beseem.

Or that starred AEthiop queen that strove

To set her beauty’s praise above

The sea-nymphs, and their powers offended.”

[See: Milton's Penseroso]

Cassiopeia is called “the starred AEthiop, queen” because after her death she was placed among the stars, forming the constellation of that name. Though she attained this honour, yet the Sea–Nymphs, her old enemies, prevailed so far as to cause her to be placed in that part of the heaven near the pole, where every night she is half the time held with her head downward, to give her a lesson of humility.

Memnon was an AEthiopian prince, of whom we shall tell in a future chapter.

[See: Memnon in Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion Jane Ellen Harrison]

THE WEDDING FEAST.

The joyful parents, with Perseus and Andromeda, repaired to the palace, where a banquet was spread for them, and all was joy and festivity. But suddenly a noise was heard of warlike clamour, and Phineus, the betrothed of the virgin, with a party of his adherents, burst in, demanding the maiden as his own. It was in vain that Cepheus remonstrated

“You should have claimed her when she lay bound to the rock, the monster’s victim. The sentence of the gods dooming her to such a fate dissolved all engagements, as death itself would have done.”

Phineus made no reply, but hurled his javelin at Perseus, but it missed its mark and fell harmless. Perseus would have thrown his in turn, but the cowardly assailant ran and took shelter behind the altar. But his act was a signal for an onset by his hand upon the guests of Cepheus.

They defended themselves and a general conflict ensued, the old king retreating from the scene after fruitless expostulations, calling the gods to witness that he was guiltless of this outrage on the rights of hospitality.

Perseus and his friends maintained for some time the unequal contest; but the numbers of the assailants were too great for them, and destruction seemed inevitable, when a sudden thought struck Perseus,

“I will make my enemy defend me.”

Then with a loud voice he exclaimed, “If I have any friend here let him turn away his eyes!” and held aloft the Gorgon’s head.

“Seek not to frighten us with your jugglery,” said Thescelus, and raised his javelin in the act to throw, and became stone in the very attitude. Ampyx was about to plunge his sword into the body of a prostrate foe, but his arm stiffened and he could neither thrust forward nor withdraw it.

Another, in the midst of a vociferous challenge, stopped, his mouth open, but no sound issuing. One of Perseus’s friends, Aconteus, caught sight of the Gorgon and stiffened like the rest. Astyages struck him with his sword, but instead of wounding, it recoiled with a ringing noise.

Phineus beheld this dreadful result of his unjust aggression, and felt confounded. He called aloud to his friends, but got no answer; he touched them and found them stone. Falling on his knees and stretching out his hands to Perseus, but turning his head away, he begged for mercy.

“Take all,” said he, “give me but my life.”

“Base coward,” said Perseus, “thus much I will grant you; no weapon shall touch you; moreover, you shall be preserved in my house as a memorial of these events.” So saying, he held the Gorgon’s head to the side where Phineus was looking, and in the very form which he knelt, with his hands outstretched and face averted, he became fixed immovably, a mass of stone!

The following allusion to Perseus is from Milman’s “Samor”:

“As ‘mid the fabled Libyan bridal stood

Perseus in stern tranquillity of wrath,

Half stood, half floated on his ankle-plumes

Out-swelling, while the bright face on his shield

Looked into stone the raging fray; so rose,

But with no magic arms, wearing alone

Th’ appalling and control of his firm look,

The Briton Samor; at his rising awe

Went abroad, and the riotous hall was mute.”

[See: Milman's Samor]