|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER V.

THE DEMONOLOGY OF GHOSTS AND SPEITES AND BOGEYS.

Ker as Evil Sprite | Ker as Bacillus | Ker as Evil Sprite | Keres Of Old Age And Death | Ker of Death | Ker As Harpy And Wind-Demon | Ker as Wind-Demoms | Ker as Fate | Ker as Gorgon | Ker as Sirens | Ker as Sphinx | Ker as Erinys | Erinyes of Aeschylus | Curse of Blood | Tragic Erinyes | Erinys As Snake | Semnai Theai | Eumenides

IN the preceding chapters the nature of Greek ritual has been discussed. The main conclusion that has emerged is that this ritual in its earlier phases was mainly characterized by a tendency to what the Greeks called airorpoirri, i.e. the turning away, the aversion of evil. This tendency was however rarely quite untouched by an impulse more akin to our modern notion of worship, the impulse of induction, the fostering of good influences.

Incidentally we have of course gathered something of the nature of the objects of worship. When the ritual was not an attempt at the direct impulsion of nature, we have had brief uncertain glimpses of sprites and ghosts and underworld divinities. It now remains to trace with more precision these vague theological or demonological or mythological outlines, to determine the character of the beings worshipped and something of the order of their development.

In theology facts are harder to seek, truth more difficult to formulate than in ritual. Ritual, i.e. what men did, is either known or not known; what they meant by what they did the connecting link between ritual and theology can sometimes be certainly known, more often precariously inferred. Still more hazardous is the attempt to determine how man thought of the objects or beings to whom his ritual was addressed, in a word what was his theology, or, if we prefer the term, his mythology.

At the outset one preliminary caution is imperative. Our minds are imbued with current classical mythology, our imagination peopled with the vivid personalities, the clear-cut outlines of the Olympian gods; it is only by a somewhat severe mental effort that we realize the fact essential to our study that there were no gods at all, that what we have to investigate is not so many actual facts and existences but only conceptions of the human mind, shifting and changing colour with every human mind that conceived them. Art which makes the image, literature which crystallizes attributes and functions, arrest and fix this shifting kaleidoscope; but, until the coming of art and literature and to some extent after, the formulary of theology is'all things are in flux' (trdvra pel).

Further, not only are we dealing solely with conceptions of the human mind, but often with conceptions of a mind that conceived things in a fashion alien to our own. There is no greater bar to that realizing of mythology which is the first condition of its being understood, than our modern habit of clear analytic thought. The very terms we use are sharpened to an over nice discrimination. The first necessity is that by an effort of the sympathetic imagination we should think back the'many'we have so sharply and strenuously divided, into the haze of the primitive 'one.'

Nor must we regard this haze of the early morning as a deleterious mental fog, as a sign of disorder, weakness, oscillation. It is not confusion or even synthesis; rather it is as it were a protoplasmic fulness and forcefulness not yet articulate into the diverse forms of its ultimate births. It may even happen, as in the case of the Olympian divinities, that articulation and discrimination sound the note of approaching decadence. As Maeterlinck beautifully puts it, la clarte parfaite nest-elle pas d ordinaire le signe de la lassitude des idees?

There is a practical reason why it is necessary to bear in mind this primary fusion, though not confusion, of ideas. Theology, after articulating the one into the many and diverse, after a course of exclusive and determined discrimination, after differentiating a number of departmental gods and spirits, usually monotheizes, i.e. resumes the many into the one. Hence, as will be constantly seen, mutatis mutandis, a late philosophizing author is often great use in illustrating a primitive conception: the multiform divinity of an Orphic Hymn is nearer to the primitive mind than the clear-cut outlines of Homers Olympians.

In our preliminary examination of Athenian festivals we found underlying the Diasia the worship of a snake, underlying the Anthesteria the revocation of souls. In the case of the Thesmophoria we found magical ceremonies for the promotion of fertility addressed as it would seem directly to the earth itself: in the Thargelia we had ceremonies of purification not primarily addressed to any one. In the Diasia and Anthesteria only was there clear evidence of some sort of definite being or beings as the object of worship. The meaning of snake-worship will come up for discussion later, for the present we must confine ourselves to the theology or demonology of the beings worshipped in the Anthesteria, the Keres, sprites, or ghosts, and the theological shapes into which they are developed and discriminated.

The Ker as Evil Sprite

That the Keres dealt with in the Anthesteria'worshipped'is of course too modern a word were primarily ghosts, admits, in the face of the evidence previously adduced, of no doubt. That in the fifth century B.C. they were thought of as little winged sprites the vase-painting in fig. 7 clearly shows, and to it might be added the evidence of countless other Athenian white lekythi where the eidolon or ghost, is shown fluttering about the grave. But to the ancients Keres a word of far larger and vaguer connotation than our modern ghosts, and we must grasp this wider connotation if we would understand the later developments of the term.

Something of their nature has already appeared in the apotropaic precautions of the Anthesteria. Pitch was smeared on the doors to catch them, cathartic buckthorn was chewed to eject them; they were dreaded as sources of evil; they were, if not exactly evil spirits, certainly spirits that brought evil: else why these precautions? Plato has this in his mind when he says 'There are many fair things in the life of mortals, but in most of them there are as it were adherent Keres which pollute and disfigure them.' Here we have not merely a philosophical notion, that there is a soul of evil in things good, but the reminiscence surely of an actual popular faith, i.e. the belief that Keres, like a sort of personified bacilli, engendered corruption and pollution. To such influences all things mortal are exposed. Conon in telling the story of the miraculous head of Orpheus says that when it was found by the fisherman'it was still singing, nor had it suffered any change from the sea nor any other of the outrages that human Keres inflict on the dead, but it was still blooming and bleeding with fresh blood.'Conon is of course a late writer, and full of borrowed poetical phrases, but the expression human Keres is not equivalent to the Destiny of man, it means rather sources of corruption inherent in man.

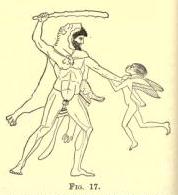

In fig. 7 we have seen a representation

of the harmless Keres, the souls fluttering out of the

grave-pithos. Fortunately ancient art has also left us a

representation of a baleful Ker. The picture in fig. 17 is from a

pelike found at Thisbe and now in the Berlin Museum. Heracles,

known by his lion skin and quiver, swings his rudely hewn club

against a tiny winged figure with shrivelled body and distorted

ugly face. We might have been at a loss to give a name to his

feeble though repulsive antagonist but for an Orphic Hymn to

Heracles which ends with the prayer:

In fig. 7 we have seen a representation

of the harmless Keres, the souls fluttering out of the

grave-pithos. Fortunately ancient art has also left us a

representation of a baleful Ker. The picture in fig. 17 is from a

pelike found at Thisbe and now in the Berlin Museum. Heracles,

known by his lion skin and quiver, swings his rudely hewn club

against a tiny winged figure with shrivelled body and distorted

ugly face. We might have been at a loss to give a name to his

feeble though repulsive antagonist but for an Orphic Hymn to

Heracles which ends with the prayer:

'Come, blessed hero, come and bring allayments

Of all diseases. Brandishing thy club,

Drive forth the baleful fates; with poisoned shafts

Banish the noisome Keres far away.'

The Ker as Bacillus

The primitive Greek leapt by his religious imagination to a forecast of the truth that it has taken science centuries to establish, i.e. the fact that disease is caused by little live things^ germs bacilli we call them, he used the word Keres. A fragment of the early comic poet Sophrori speaks of Herakles throttling Hepiales. Hepiales must be the demon of nightmare, well known to us from other sources and under various confused names as Ephialtes, Epiales, Hepialos. The Etymologicon Magnum explains 'Hepialos' as a shivering fever and'a daimon that comes upon those that are asleep.' It has been proposed to regard the little winged figure which Herakles is clearly taking by the throat as Hepiales, demon of nightmare, rather than as a Ker. The question can scarcely be decided, but the doubt is as instructive as any certainty. Hepiales is a disease caused by a Ker; i.e. it is a special form of Ker, the nightmare bacillus. Blindness also was caused by a Ker, as was madness; hence the expression casting a black Ker on their eyes.' Blindness and madness, blindness of body and spirit are scarcely distinguished, as in the blindness of Oedipus; both come of the Keres-Erinyes.

To the primitive mind all diseases are caused by, or rather are, bad spirits. Porphyry tells us that blisters are caused by evil spirits which come at us when we eat certain food and settle on our bodies. He goes to the very heart of ancient religious 'aversion' when he adds that it is on account of this that purifications are practised, not in order that we may induce the presence of the gods, but that these wretched things may keep off. He might have added, it is on account of these bad spirits that we fast; indeed ayveLa, the word he uses, means abstinence as well as purity. Eating is highly dangerous because you have your mouth open and a Ker may get in. If a Ker should get in when you are about to partake of specially holy food there will naturally be difficulties. So argues the savage. Porphyry being a vegetarian says that these bad spirits specially delight in blood and impurities generally and they 'creep into people who make use of such things.' If you kept about you holy plants with strong scents and purging properties, like rue and buckthorn, you might keep the Keres away, or, if they got in, might speedily and safely eject them.

The physical character of the Keres, their connection with 'the lusts of the flesh' comes out very clearly in a quaint moralising poem preserved by Stobaeus and attributed to Linos. It deals with the dangers of Keres and the necessity for meeting them by'purification.'Its ascetic tone and its attribution to Linos probably point to Orphic origin. It runs as follows:

'Hearken to these my sayings, zealously lend me your hearing

To the simple truth about all things. Drive far away the disastrous

Keres, they who destroy the herd of the vulgar and fetter

All things around with curses manifold. Many and dreadful

Shapes do they take to deceive. But keep them far from thy spirit,

Ever watchful in mind. This is the purification

That shall rightly and truly purge thee to sanctification

(If but in truth thou hatest the baleful race of the Keres),

And most of all thy belly, the giver of all things shameful,

For desire is her charioteer and she drives with the driving of madness.'

It is commonly said that diseases are 'personified' by the Greeks. This is to invert the real order of primitive thought. It is not that a disease is realized as a power and then turned into a person, it is that primitive man seems unable to conceive of any force except as resulting from some person or being or sprite, something a little like himself. Such is the state of mind of the modern Greek peasant who writes XoXepa with a capital letter. Hunger, pestilence, madness, nightmare have each a sprite behind them; are all sprites.

The Ker as Evil Sprite

Of course, as Hesiod knew, there were ancient golden days when these sprites were not let loose, when they were shut up safe in a cask and

'Of old the tribes of mortal men on earth

Lived without ills, aloof from grievous toil

And catching plagues which Keres gave to men.'

But alas !

'The woman with her hands took the great lid

From off the cask and scattered them, and thus

Devised sad cares for mortals. Hope alone

Kemained therein, safe held beneath the rim,

Nor flitted forth, for she thrust to the lid.'

Who the woman was and why she opened the jar will be considered later; for the moment we have only to note what manner of things came out of it. The account is strange and significant. She shut the cask too late:

'For other myriad evils wandered forth

To man, the earth was full, and full the sea.

Diseases, that all round by day and night

Bring ills to mortals, hovered, self-impelled,

Silent, for Zeus the Counsellor their voice

Had taken away.'

Proclus understands that these silent ghostly insidious things are Keres, though he partly modernizes them. He says in commenting on the passage, 'Hesiod gives them (i.e. the diseases) bodily form making them approach without sound, showing that even of these things spirits are the guardians, sending invisibly the diseases decreed by fate and scattering the Keres in the cask.' After the manner of his day he thinks the Keres were presided over by spirits, that they were diseases sent by spirits, but primitive man believes the Keres are the spirits, are the diseases. Hesiod himself was probably not quite conscious that the jar or pithos was the great grave-jar of the Earth-mother Pandora, and that the Keres were ghosts. 'Earth,'says Hesiod,'was full and full the sea.' This crowd of Keres close-packed is oddly emphasized in a fragment by an anonymous poet:

'Such is our mortal state, ill upon ill,

And round about us Keres crowding still;

No chink of opening

Is left for entering.'

This notion of the swarm of unknown unseen evils hovering about men haunts the lyric poets, lending a certain primitive reality to their vague mournful pessimism. Simonides of Amorgos seems to echo Hesiod when he says 'hope feeds all men' but hope is all in vain because of the imminent demon host that work for man's undoing, disease and death and war and shipwreck suicide.

'No ill is lacking, Keres thousand-fold

Mortals attend, woes and calamities

That none may scape.'

Here and elsewhere to translate 'Keres' by fates is to make a premature abstraction. The Keres are still physical actual things not impersonations. So when Aeschylus puts into the mouth of his Danaid women the prayer

'Nor may diseases, noisome swarm,

Settle upon our heads, to harm

Our citizens,'

the 'noisome swarm' is no mere 'poetical' figure but the reflection of a real primitive conviction of live pests.

The little fluttering insect-like diseases are naturally spoken of for the most part in the plural, but in the Philoctetes of Sophocles the festering sore of the hero is called 'an ancient Ker'; here again the usage is primitive rather than poetical. Viewing the Keres 'as little inherent physical pests,' we are not surprised to learn from Theognis that

'For hapless man wine doth two Keres hold

Limb-slacking Thirst, Drunkenness overbold.'

Nor is it man alone who is beset by these evil sprites. In that storehouse of ancient superstition, the Orphic Lithica*, we hear of Keres who attack the fields. Against them the best remedy is the Lychnis stone, which was also good to keep off a hailstorm.

'Lychnis, from pelting hail be thou our shield,

Keep off the Keres who attack each field.'

And Theophrastus tells us that each locality has its own Keres dangerous to plants, some coming from the ground, some from the air, some from both. Fire also, it would seem, might be infested by Keres. A commentator on Philo says that it is important that no profane fire, i.e. such as is in ordinary use, should touch an altar because it may be contaminated by myriads of Keresy Instructive too is the statement of Stesichorus, who according to tradition 'called the Keres by the name Telchines.' Eustathius in quoting the statement of Stesichorus adds as explanatory of Keres tas crcotwcret: the word ovcorcocret is late and probably a gloss, it means darkening, killing, eclipse physical and spiritual. Leaving the gloss aside, the association of Keres with Telchines is of capital interest and takes us straight back into the world of ancient magic. The Telchines were the typical magicians of antiquity, and Strabo tells us that one of their magic arts was to 'besprinkle animals and plants with the water of Styx and sulphur mixed with it, with a view to destroy them.'

Thus the Keres, from being merely bad influences inherent and almost automatic, became exalted and personified into actual magicians. Eustathius in the passage where he quotes Stesichorus allows us to see how this happened. He is commenting on the ancient tribe of the Kouretes: these Kouretes, he says, were Cretan and also called Thelgines (sic), and they were sorcerers and magicians.' Of these there were two sorts: one sort craftsmen and skilled in handiwork, the other sort pernicious to all good things; these last were of fierce nature and were fabled to be the origins of squalls of wind, and they had a cup in which they used to brew magic potions from roots. They (i.e. the former sort) invented statuary and discovered metals, and they were amphibious and of strange varieties of shape, some were like demons, some like men, some like fishes, some like serpents; - and the story went that some had no hands, some no feet, and some had webs between their fingers like geese. And they say that they were blue-eyed and black-tailed.' Finally comes the significant statement that they perished struck down by the thunder of Zeus or by the arrows of Apollo. The old order is slain by the new. To the imagination of the conqueror the conquered are at once barbarians and magicians, monstrous and magical, hated and feared, craftsmen and medicine men, demons, beings endowed like the spirits they worship, in a word Keres- Telchines. When we find the good, fruitful, beneficent side of the Keres effaced and ignored we must always remember this fact that we see them through the medium of a conquering civilization.

The Keres Of Old Age And DeathTHE KERES OF OLD AGE AND DEATH.

By fair means or foul, by such ritual procedures as have already been noted, by the chewing of buckthorn, the sounding of brass, the making of comic figures, most of the Keres could be kept at bay; but there were two who waited relentless, who might not be averted, and these were Old Age and Death. It is the thought that these two Keres are waiting that with the lyric poets most of all overshadows the brightness of life. Theognis prays to Zeus:

'Keep far the evil Keres, me defend

From Old Age wasting, and from Death the end.'

These haunting Keres of disease, disaster, old age and death Mimnermus can never forget:

'We blossom like the leaves that come in spring, What time the sun begins to flame and glow,

And in the brief span of youth's gladdening

Nor good nor evil from the gods we know,

But always at the goal black Keres stand

Holding, one grievous Age, one Death within her hand.

And all the fruit of youth wastes, as the Sun

Wastes and is spent in sunbeams, and to die

Not live is best, for evils many a one

Are born within the soul. And Poverty

Has wasted one man's house with niggard care,

And one has lost his children. Desolate

Of this his earthly longing, he must fare

To Hades. And another for his fate

Has sickness sore that eats his soul. No man

Is there but Zeus hath cursed with many a ban.

Here is the same dismal primitive faith, or rather fear. All things are beset by Keres, and Keres are all evil. The verses of Mimnermus are of interest at this point because they show the emergence of the two most dreaded Keres, Old Age and Death, from the swarm of minor ills. Poverty, disease and desolation are no longer definitely figured as Keres.

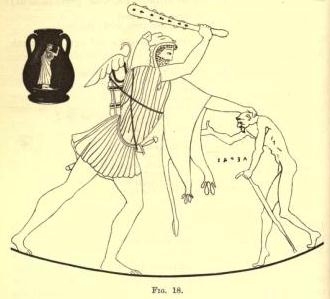

The vase-painter shows this fact in

a cruder form. On a red-figured amphora (fig. 18) in the Louvre

Herakles is represented lifting his club to slay a shrivelled

ugly little figure leaning on a stick the figure obviously is an

old man. Fortunately it is inscribed yrjpas. It is not an old man, but Old Age itself,

the dreaded Ker. The representation is a close parallel to

Herakles slaying the Ker in fig. 17. The Ker of Old Age has no

wings: these the vase-painter rightly felt were inappropriate. It

is in fact a Ker developed one step further into an

impersonation. The vase may be safely dated as belonging to about

the middle of the 5th century B.C. It is analogous in style, as

in subject, to an amphora in the British Museum bearing the

love-name Charmides.

The vase-painter shows this fact in

a cruder form. On a red-figured amphora (fig. 18) in the Louvre

Herakles is represented lifting his club to slay a shrivelled

ugly little figure leaning on a stick the figure obviously is an

old man. Fortunately it is inscribed yrjpas. It is not an old man, but Old Age itself,

the dreaded Ker. The representation is a close parallel to

Herakles slaying the Ker in fig. 17. The Ker of Old Age has no

wings: these the vase-painter rightly felt were inappropriate. It

is in fact a Ker developed one step further into an

impersonation. The vase may be safely dated as belonging to about

the middle of the 5th century B.C. It is analogous in style, as

in subject, to an amphora in the British Museum bearing the

love-name Charmides.

Gradually the meanings of Ker became narrowed down to one, to the great evil, death and the fate of death, but always with a flitting remembrance that there were Keres of all mortal things. This is the usage most familiar to us, because it is Homeric. Homer's phraseology is rarely primitive often fossilized and the regularly recurring 'Ker of death' is heir to a long ancestry. In Homer we catch the word Ker at a moment of transition; it is half death, half death-spirit. Odysseus says

'Death and the Ker avoiding, we escape,'

where the two words death and Ker are all but equivalents: they are both death and the sprite of death, or as we might say now-a-days death and the angel of death. Homer's conception so dominates our minds that the custom has obtained of uniformly translating 'Ker' by fate, a custom that has led to much confusion of thought.

The Ker of Death

Two things with respect to Homer's usage must be borne in mind. First, his use of the word Ker is, as might be expected, far more abstract and literary than the usage we have already noted. It is impossible to say that Homer has in his mind anything of the nature of a tiny winged bacillus. Second, in Homer Ker is almost always defined and limited by the genitive Oavaroio, and this looks as though, behind the expression, there lay the half-conscious knowledge that there were Keres of other things than death. Ker itself is not death, but the two have become well-nigh inseparable.

Some notion of the double nature, good and bad, of Keres seems to survive in the expression two-fold Keres. Achilles says:

'My goddess-mother silver-footed Thetis

Hath said that Keres two-fold bear me on

To the term of death.'

It is true that both the Keres are carrying him deathward, but there is strongly present the idea of the diversity of fates. The English language has in such cases absolutely no equivalent for Ker, because it has no word weighted with the like associations.

In one passage only in the Iliad, i.e. the description of the shield of Achilles, does a Ker actually appear in person, on the battlefield:

'And in the thick of battle there was Strife

And Clamour, and there too the baleful Ker.

She grasped one man alive, with bleeding wound,

Another still unwounded, and one dead

She by his feet dragged through the throng. And red

Her raiment on her shoulders with men's blood.'

A work of art, it must be remembered, is being described, and the feeling is more Hesiodic than Homeric. The Ker is in this case not a fate but a horrible she-demon of slaughter.

The Ker As Harpy And Wind-Demon

In Homer the Keres are no doubt mainly death-spirits, but they have another function, they actually carry off the souls to Hades. Odysseus says:

'Howbeit him Death - Keres carried off

To Hades'house.'

It is impossible here to translate Keres by 'fates' the word is too abstract: the Keres are angels, messengers, death-demons, souls that carry off souls.

The idea that underlies this

constantly recurring formulary emerges clearly when we come to

consider those analogous apparitions, the Harpies. The Harpies

betray their nature clearly in their name, in its uncontracted

form anbqriim,' which appears on the

vase-painting in fig. 19; they are the Snatchers, winged

women-demons, hurrying along like the storm wind and carrying all

things to destruction.

The idea that underlies this

constantly recurring formulary emerges clearly when we come to

consider those analogous apparitions, the Harpies. The Harpies

betray their nature clearly in their name, in its uncontracted

form anbqriim,' which appears on the

vase-painting in fig. 19; they are the Snatchers, winged

women-demons, hurrying along like the storm wind and carrying all

things to destruction.

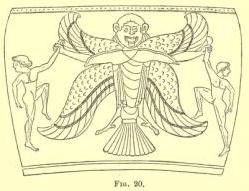

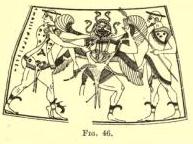

The vase-painting in fig. 19 from a large black-figured vessel in the Berlin Museum is specially instructive because, though the winged demons are inscribed as Harpies, the scene of which they form part, i.e. the slaying of Medusa, clearly shows that they are Gorgons; so near akin, so shifting and intermingled are the two conceptions. On another vase (fig. 20), also in the Berlin Museum,

we see an actual Gorgon with the typical Gorgon's head and protruding tongue performing the function of a Harpy, i.e. of a Snatcher. We say 'an actual Gorgon,' but it

is not a Gorgon of the usual form but a bird-woman with a

Gorgon's head. The bird-woman is currently and rightly associated

with the Siren, a creature to be discussed later, a creature

malign though seductive in Homer, but gradually softened by the

Athenian imagination into a sorrowful death angel.

We say 'an actual Gorgon,' but it

is not a Gorgon of the usual form but a bird-woman with a

Gorgon's head. The bird-woman is currently and rightly associated

with the Siren, a creature to be discussed later, a creature

malign though seductive in Homer, but gradually softened by the

Athenian imagination into a sorrowful death angel.

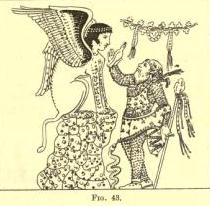

The tender bird-women of the

so-called'Harpy tomb'from Lycia (fig. 21), now in the British

Museum, perform the functions of a Harpy, but very gently. They

are at least near akin to the sorrowing Sirens on Athenian tombs.

We can scarcely call them by the harsh name of the 'Snatchers.'

And yet, standing as it did in Lycia, this 'Harpy tomb' may be

the outcome of the same stratum of mythological conceptions as

the familiar story of the daughters of the Lycian Pandareos.

Penelope in her desolation cries aloud:

The tender bird-women of the

so-called'Harpy tomb'from Lycia (fig. 21), now in the British

Museum, perform the functions of a Harpy, but very gently. They

are at least near akin to the sorrowing Sirens on Athenian tombs.

We can scarcely call them by the harsh name of the 'Snatchers.'

And yet, standing as it did in Lycia, this 'Harpy tomb' may be

the outcome of the same stratum of mythological conceptions as

the familiar story of the daughters of the Lycian Pandareos.

Penelope in her desolation cries aloud:

'Would that the storm might snatch me adown its dusky way

And cast me forth where Ocean is outpour'd with ebbing spray,

As when Pandareos' daughters the storm winds bore away,'

and then, harking back, she tells the ancient Lycian story of the fair nurture of the princesses and how Aphrodite went to high Olympus to plan for them a goodly marriage. But whom the gods love die young:

Meantime the Harpies snatched away the maids, and gave them o'er

To the hateful ones, the Erinyes, to serve them evermore.'

'Early death was figured by the primitive Greek as a snatching away by evil death-demons, storm-ghosts. These snatchers he called Harpies, the modern Greek calls them Nereids. In Homer's lines we seem to catch the winds as snatchers, half-way to their full impersonation as Harpies. To give them a capital letter is to crystallize their personality prematurely. Even when they become fully persons, their name carried to the Greek its adjectival sense now partly lost to us.

Another function of the Harpies links them very closely with the Keres, and shows in odd and instructive fashion the animistic habit of ancient thought. The Harpies not only snatch away souls to death but they give life, bringing things to birth. A Harpy was the mother by Zephyros of the horses of Achilles. Both parents are in a sense winds, only the Harpy wind halts between horse and woman. By winds as Vergil tells us mares became pregnant.

The Ker as Wind-demon

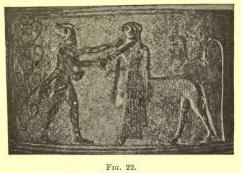

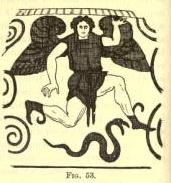

As such a Harpy, half horse, half

Gorgon-woman, Medusa is represented on a curious Boeotian vase

(fig. 22) of very archaic style now in the Louvre. The

representation is instructive, it shows how in art as in

literature the types of Gorgon and Harpy were for a time in flux;

a particular artist could please his own fancy. The horse Medusa

was apparently not a success, for she did not survive.

As such a Harpy, half horse, half

Gorgon-woman, Medusa is represented on a curious Boeotian vase

(fig. 22) of very archaic style now in the Louvre. The

representation is instructive, it shows how in art as in

literature the types of Gorgon and Harpy were for a time in flux;

a particular artist could please his own fancy. The horse Medusa

was apparently not a success, for she did not survive.

It is easy enough to see how winds were conceived of as Snatchers, death-demons, but why should they impregnate, give life? It is not, I think, by a mere figure of speech that breezes are spoken of as 'life-begetting' and 'soul-rearing'. It is not because they are in our sense life-giving and refreshing as well as destructive: the truth lies deeper down. Only life can give life, only a soul gives birth to a soul; the winds are souls as well as breaths. Here as so often we get at the real truth through an ancient Athenian cultus practice. When an Athenian was about to be married he prayed and sacrificed, Suidas tells us, to the Tritopatores. The statement is quoted from Phanodemus who wrote a book on Attic Matters.

Suidas tells us also who the Tritopatores were. They were, as we might guess from their name, fathers in the third degree, fore-fathers, ancestors, ghosts, and Demon in his Atthis said they were winds. To the winds, it has already been seen, are offered such expiatory sacrifices (crcfxiyia) as are due to the spirits of the underworld. The idea that the Tritopatores were winds as well as ghosts was never lost. To Photius and Suidas they are'lords of the winds'and the Orphics make them 'gate-keepers and guardians of the winds.' From ghosts of dead men, Hippocrates tells us, came nurture and growth and seeds, and the author of the Geoponica says that winds give life not only to plants but to all things. It was natural enough that the winds should be divided into demons beneficent and maleficent, as it depends where you live whether a wind from a particular quarter will do you good or ill.

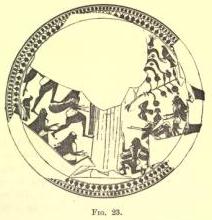

In the black-figured vase-painting

in fig. 23, found at Naukratis and now in the British Museum, a

local nymph is depicted: only hair and her feet, but she must be

the nymph Gyrene beloved of Apollo, for close to her and probably

held in her hand is a great branch of the silphium plant. To

right of her approaching to minister or to worship are winged

genii. It is the very image of oepateia, tendance, ministration, fostering care,

worship, all in one. The genii tend the nymph who is the land

itself, her and her products. The figures to the right are

bearded: they can scarcely be other than the spirits of the North

wind, the Boreadae, the cool healthful wind that comes over the

sea to sun-burnt Africa. If these be Boreadae, the opposing

figures, beardless and therefore almost certainly female, are

Harpies, demons of the South wind, to Africa the wind coming

across the desert and bringing heat and blight and

pestilence.

In the black-figured vase-painting

in fig. 23, found at Naukratis and now in the British Museum, a

local nymph is depicted: only hair and her feet, but she must be

the nymph Gyrene beloved of Apollo, for close to her and probably

held in her hand is a great branch of the silphium plant. To

right of her approaching to minister or to worship are winged

genii. It is the very image of oepateia, tendance, ministration, fostering care,

worship, all in one. The genii tend the nymph who is the land

itself, her and her products. The figures to the right are

bearded: they can scarcely be other than the spirits of the North

wind, the Boreadae, the cool healthful wind that comes over the

sea to sun-burnt Africa. If these be Boreadae, the opposing

figures, beardless and therefore almost certainly female, are

Harpies, demons of the South wind, to Africa the wind coming

across the desert and bringing heat and blight and

pestilence.

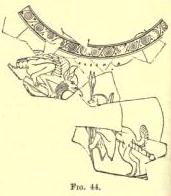

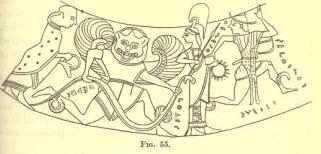

It might be bold to assert so much, but for the existence of another vase-painting on a situla from Daphnae (fig. 24), also, happily for comparison, in the British Museum. On the one side, not figured here, is a winged bearded figure ending in a snake, probably Boreas: such a snake-tailed Boreas was seen by Pausanias on the chest of Cypselus in the act of seizing Oreithyia. There is nothing harsh in the snake tail for Boreas, for the winds, as has already been noted, were regarded as earth-born.

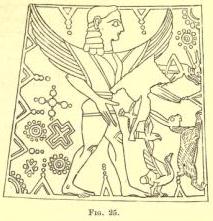

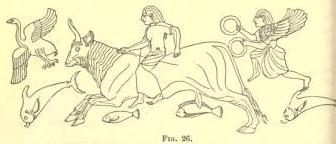

Behind Boreas is a plant in blossom

rising from the ground, a symbol of the vegetation nourished by

the North wind. On the reverse (fig. 25) is a winged figure

closely like the left hand genii of the Gyrene cylix, and this

figure drives in front of it destructive creatures, a locust, the

pest of the South, two birds of prey attacking a hare, and a

third that is obviously a vulture.

Behind Boreas is a plant in blossom

rising from the ground, a symbol of the vegetation nourished by

the North wind. On the reverse (fig. 25) is a winged figure

closely like the left hand genii of the Gyrene cylix, and this

figure drives in front of it destructive creatures, a locust, the

pest of the South, two birds of prey attacking a hare, and a

third that is obviously a vulture.

The two representations taken

together justify us in regarding the left hand genii as

destructive. Taking these two representations together with a

third vase-painting, the celebrated Phineus cylix, we are further

justified in calling these destructive wind-demons Harpies.

The two representations taken

together justify us in regarding the left hand genii as

destructive. Taking these two representations together with a

third vase-painting, the celebrated Phineus cylix, we are further

justified in calling these destructive wind-demons Harpies.

On this vase the Boreadae, Zetes and Kalais, show their true antagonism. The Harpies have fouled the food of Phineus like the pestilential winds they were, and the clean clear sons of the North wind give chase.

It is seldom that ancient art has preserved for us so clear a picture of the duality of things.

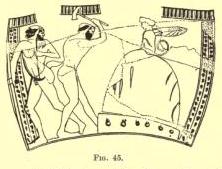

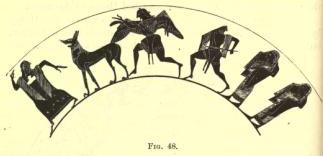

On black-figured vase-paintings little winged figures occur

not unfrequently to which it is by no means easy to give a name.

In fig. 26 we have such a representation Europa seated on the

bull passes in rapid flight over the sea which is indicated by

fishes and dolphins. In front of her flies a vulture-like bird,

behind comes a winged figure holding two wreaths.

Is she Nike, bringing good success to the lover? Is she a favouring wind speeding the flight? I incline to think the vase-painter did not clearly discriminate. She is a sort of good Ker, a fostering favouring influence. In all these cases of early genii it is important to bear in mind that the sharp distinction between moral and physical influence, so natural to the modern mind, is not yet established.

We return to the Keres from which the wind demons sprang.

The Ker as Fate

One Homeric instance of the use of Ker remains to be examined. When Achilles had the fourth time chased Hector round the walls of Troy, Zeus was wearied and

'Hung up his golden scales and in them set

Twain Keres, fates of death that lays men low.'

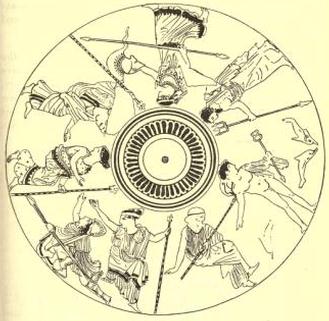

This weighing of Keres, this 'Kerostasia,' is a weighing of death fates, but it is interesting to find that it reappears under another name, i.e. the 'Psychostasia,' the weighing of souls. We know from Plutarch that Aeschylus wrote a play with this title. The subject was the weighing of the souls or lives not of Hector and Achilles, but Achilles and Memnon. This is certain because, Plutarch says, he placed at either side of the scales the mothers Thetis and Eos praying for their sons. Pollux adds that Zeus and his attendants were suspended from a crane. In the scene of the Kerostasia as given by Quintus Smyrnaeus, a scene which probably goes back to the earlier tradition of 'Arctinos, 'it is noticeable that Memnon the loser has a swarthy Ker while Achilles the winner has a bright cheerful one, a fact which seems to anticipate the white and black Erinyes.

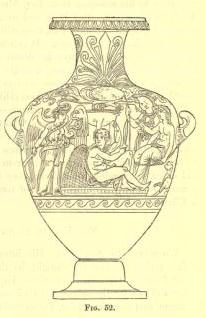

The scene of the Psychostasia or

Kerostasia, as it is variously called, appears on several

vase-paintings, one of which from the British Museum is

reproduced in fig. 27. Hermes holds the scales, in either scale

is the Ker or eidolon of one of the combatants; the lekythos is

black-figured, and is our earliest source for the Kerostasia. The

Keres are represented as miniature men, it is the lives rather

than the fates that are weighed. So the notion shifts.

The scene of the Psychostasia or

Kerostasia, as it is variously called, appears on several

vase-paintings, one of which from the British Museum is

reproduced in fig. 27. Hermes holds the scales, in either scale

is the Ker or eidolon of one of the combatants; the lekythos is

black-figured, and is our earliest source for the Kerostasia. The

Keres are represented as miniature men, it is the lives rather

than the fates that are weighed. So the notion shifts.

In Hesiod, as has already been noted, the Keres are more primitive and actual, they are in a sense fates, but they are also little winged spirits. But Hesiod is Homer-ridden, so we get the 'black Ker,' own sister to Thanatos and hateful Moros (Doom) and Sleep and the tribes of Dreams. We get also the dawnings of an Erinys, of an avenging fate, though the lines look like an interpolation:

'Night bore

The Avengers and the Keres pitiless.'

Hesiod goes on to give the names usually associated with the Fates, Klotho, Lachesis, Atropos, and says they

'To mortals at their birth

Give good and evil both.'

Whether interpolated or not the passage is significant both because it gives to the Keres the functions Homer allotted to the Erinyes, and also because with a reminiscence of earlier thought it makes them the source of good and of evil. It is probably this last idea that is at the back of the curious Hesiodic epithet Krjpi,Tpptfs, which occurs in the Works and Days':

'Then, when the dog-star comes and shines by day

For a brief space over the heads of men

Ker-nourished.'

'Men nourished for death'assuredly is not the meaning; the idea seems to be that each man has a Ker within him, a thing that nourishes him, keeps him alive, a sort of fate as it were on which his life depends. The epithet might come to signify something like mortal, subject to, depending on fate. If this be the meaning it looks back to an early stage of things when the Ker had not been specialized down to death and was not wholly'black,'when it was more a man's luck than his fate, a sort of embryo Genius.

Ker-nourished, would then be the antithesis of 'slain by Keres,' which Hesychius explains as those who died of disease; and would look back to a primitive doubleness of functions when the Keres were demons of all work. In vague and fitful fashion they begin where the Semnae magnificently end, as Moirae with control over all human weal and woe.

'These for their guerdon hold dominion

O'er all things mortal.'

In such returning cycles runs the wheel of theology.

But the black side of things is always, it would seem, most impressive to primitive man. Given that the Ker was a fate of death, almost a personified death, it was fitting and natural that it should be tricked out with ever increasing horrors. Hesiod, or the writer of the Shield, with his rude peasant imagination was ready for the task. The Keres of Pandora's jar are purely primitive, and quite natural, not thought out at all: the Keres of the Shield are a literary effort and much too horrid to be frightening. Behind the crowd of old men praying with uplifted hands for their fighting children stood

'The blue-black Keres, grinding their white teeth,

Glaring and grim, bloody, insatiable;

They strive round those that fall, greedy to drink

Black blood, and whomsoever first they found

Low lying with fresh wounds, about his flesh

A Ker would lay long claws, and his soul pass

To Hades and chill gloom of Tartarus.'

Pausanias in his description of the chest of Cypselus tells of the figure of a Ker which is thoroughly Hesiodic in character. The scene is the combat between Eteokles and Polyneikes; Polyneikes has fallen on his knees and Eteokles is rushing at him.' Behind Polyneikes is a woman-figure with teeth, as cruel as a wild beast's, and her finger-nails are hooked. An inscription near her says that she is a Ker, as though Polyneikes were carried off by Fate, and as though the end of Eteokles were in accordance with justice.' Pausanias regards the word Ker as the equivalent of Fate, but we must not impose a conception so abstract on the primitive artist who decorated the chest.

We are very far from the little fluttering ghosts, the winged bacilli, but there is a touch of kinship with those other ghosts who in the Nekuia draw nigh to drink the black blood (p. 75), and a forecast of the Erinyes the 'blue-black' Keres are near akin to the horrid Hades demon painted by Polygnotus on the walls of the Lesche at Delphi. Pausanias says, 'Above the figures I have mentioned (i.e. the sacrilegious man, etc.) is Eurynomos; the guides of Delphi say that Eurynomos is one of the demons in Hades, and that he gnaws the flesh of the dead bodies, leaving only the bones. Homer's poem about Odysseus, and those called the Minyas and the Nostoi, though they all make mention of Hades and its terrors, know no demon Eurynomos. I will therefore say this much, I will describe what sort of a person Eurynomos is and in what fashion he appears in the painting. The colour is blue-black like the colour of the flies that settle on meat; he is showing his teeth and is seated on the skin of a vulture.'The Keres of the Shield are human vultures; Eurynomos is the sarcophagus incarnate, the great carnivorous vulture of the underworld, the flesh-eater grotesquely translated to a world of shadows. He rightly sits upon a vulture's skin. Such figures, Pausanias truly observes, are foreign to the urbane Epic. But rude primitive man, when he sees a skeleton, asks who ate the flesh; the answer is'a Ker.' We are in the region of mere rude bogeydom, the land of Gorgo, Empusa, Lamia and Sphinx, and, strange though it may seem of Siren.

To examine severally each of these bogey forms would lead too far afield, but the development of the types of Gorgon, Siren and Sphinx both in art and literature is so instructive that at the risk of digression each of these forms must be examined somewhat in detail.

The Ker as Gorgon

The Gorgons are to the modern mind three sisters of whom one, most evil of the three, Medusa, was slain by Perseus, and her lovely terrible face had power to turn men into stone.

The triple form is not primitive, it is merely an instance of a general tendency, to be discussed later a tendency which makes of each woman-goddess a trinity, which has given us the Horae, the Charites, the Semnae, and a host of other triple groups. It is immediately obvious that the triple Gorgons are not really three but one - two. The two unslain sisters are mere superfluous appendages due to convention; the real Gorgon is Medusa. It is equally apparent that in her essence Medusa is a head and nothing more; her potency only begins when her head is severed, and that potency resides in the head; she is in a word a mask with a body later appended. The primitive Greek knew that there was in his ritual a horrid thing called a Gorgoneion, a grinning mask with glaring eyes and protruding beast-like tusks and pendent tongue. How did this Gorgoneion come to be? A hero had slain a beast called the Gorgon, and this was its head. Though many other associations gathered round it, the basis of the Gorgoneion is a cultus object, a ritual mask misunderstood. The ritual object comes first; then the monster is begotten to account for it; then the hero is supplied. to account for the slaying of the monster.

Ritual masks are part of the appliances of most primitive cults. They are the natural agents of a religion of fear and 'riddance.'Most anthropological museums contain specimens of 'Gorgoneia' still in use among savages, Gorgoneia which are veritable Medusa heads in every detail, glaring eyes, pendent tongue, protruding tusks. The function of such masks is permanently to 'make an ugly face,' at you if you are doing wrong, breaking your word, robbing your neighbour, meeting him in battle; for you if you are doing right.

Scattered notices show us that masks and faces were part of the apparatus of a religion of terror among the Greeks. There was, we learn from the lexicographers, a goddess Praxidike, Exactress of Vengeance, whose images were heads only, and her sacrifices the like. By the time of Pausanias this head or mask goddess had, like the Erinys, taken on a multiple, probably a triple form. At Haliartos in Boeotia he saw in the open air'a sanctuary of the goddesses whom they call Praxidikae. Here the Haliartans swear, but the oath is not one that they take lightly.' In like manner at ancient Pheneus, there was a thing called the Petroma which contained a mask of Demeter with the surname of Cidaria: by this Petroma most of the people of Pheneus swore on the most important matters. If the mask like its covering were of stone, such a stone-mask may well have helped out the legend of Medusa. The mask enclosed in the Petroma was the vehicle of the goddess: the priest put it on when he performed the ceremony of smiting the Underground Folk with rods.

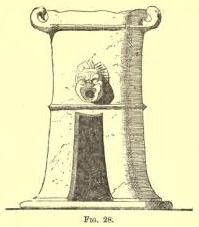

The use of masks in regular ritual was

probably a rare survival, and would persist only in remote

regions, but the common people were slow to lose their faith in

the apotropaic virtue of an 'ugly face.' Fire was a natural

terror to primitive man and all operations of baking beset by

possible Keres. Therefore on his ovens he thought it well to set

a Gorgon mask.

The use of masks in regular ritual was

probably a rare survival, and would persist only in remote

regions, but the common people were slow to lose their faith in

the apotropaic virtue of an 'ugly face.' Fire was a natural

terror to primitive man and all operations of baking beset by

possible Keres. Therefore on his ovens he thought it well to set

a Gorgon mask.

In fig. 28, a portable oven now in the museum at Athens, the mask is outside guarding the entrance.

In fig. 29 the upper part of a similar

oven is shown, and inside, where the fire flames up, are set

three masks. These ovens are not very early, but they are

essentially primitive.

In fig. 29 the upper part of a similar

oven is shown, and inside, where the fire flames up, are set

three masks. These ovens are not very early, but they are

essentially primitive.

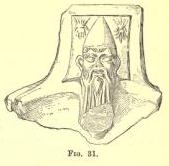

The face need not be of the type we call a Gorgon. In fig. 30 we have a Satyr type, bearded, with stark upstanding ears and hair, the image of fright set to frighten the frightful.

It might be

the picture of Phobos himself.

It might be

the picture of Phobos himself.

In fig. 31 we have neither Gorgon nor Satyr but that typical bogey of the workshop, the Cyclops. He wears the typical workman's cap, and to either side are set the thunderbolts it is his business to forge.

The craftsman is regarded as an uncanny bogey himself, cunning over-much, often deformed, and so he is good to frighten other bogeys.

The Cyclops was a terror even in high Olympus. Callimachus in his charming way tells how

'Even the little goddesses are in a dreadful fright;

If one of them will not be good, up in Olympos'height,

Her mother calls a Cyclops, and there is sore disgrace,

And Hermes goes and gets a coal, and blacks his dreadful face,

And down the chimney comes. She runs straight to her mother's lap,

And shuts her eyes tight in her hands for fear of dire mishap.'

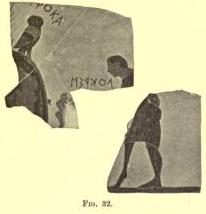

This fear of the bogey that beset the potter, and indeed beset every action, even the simplest, of human life, is very well shown in the Hymn 'The Oven, or the Potters,'which shows clearly the order of beings against which the 'ugly face' was efficacious:

If you but pay me my hire, potters, I sing to command.

Hither, come hither, Athene, bless with a fostering hand

Furnace and potters and pots, let the making and baking go well;

Fair shall they stand in the streets and the market, and quick shall they sell,

Great be the gain. But if at your peril you cheat me my price,

Tricksters by birth, then straight to the furnace I call in a trice

Mischievous imps one and all, Crusher and Crasher by name,

Smasher and Half-bake and Him-who-burns-with-Unquenchable-Flame,

They shall scorch up the house and the furnace, ruin it, bring it to nought.

Wail shall the potters and snort shall the furnace, as horses do snort.'

How real was the belief in these evil sprites and in the power to avert them by magic and apotropaic figures is seen on a fragment of early Corinthian pottery now in the Berlin Museum reproduced in fig. 32.

Here is the great oven and here is the

potter hard at work, but he is afraid in his heart, afraid of the

Crusher and the Smasher and the rest. He has done what he can; a

great owl is perched on the oven to protect it, and in front he

has put a little ugly comic man, a charm to keep off evil

spirits: he might have put a Satyr-head or a Gorgoneion; he often

did put both; it is all the same. Pollux tells us it was the

custom to put such comic figures before bronze-foundries; they

could be either hung up or modelled on the furnace, and their

object was 'the aversion of ill-will'. These little images were

also called ftacncavia or by the

unlearned trpoffaarcavia, charms

against the evil eye; and if we may trust the scholiast on

Aristophanes they formed part of the furniture of most people's

chimney corners at Athens. Of such ftaa-Kavia the Gorgon mask was one and perhaps

the most common shape.

Here is the great oven and here is the

potter hard at work, but he is afraid in his heart, afraid of the

Crusher and the Smasher and the rest. He has done what he can; a

great owl is perched on the oven to protect it, and in front he

has put a little ugly comic man, a charm to keep off evil

spirits: he might have put a Satyr-head or a Gorgoneion; he often

did put both; it is all the same. Pollux tells us it was the

custom to put such comic figures before bronze-foundries; they

could be either hung up or modelled on the furnace, and their

object was 'the aversion of ill-will'. These little images were

also called ftacncavia or by the

unlearned trpoffaarcavia, charms

against the evil eye; and if we may trust the scholiast on

Aristophanes they formed part of the furniture of most people's

chimney corners at Athens. Of such ftaa-Kavia the Gorgon mask was one and perhaps

the most common shape.

In literature the Gorgon first meets us

as a Gorgoneion, and this Gorgoneion is an underworld bogey.

Odysseus in Hades would fain have held further converse with dead

heroes, but Homer is quite non-committal as to who and what the

awful monster is; all that is clear is that the head only is

feared as an atrorpotraiov, a bogey to

keep you off. Whether he knew of an actual monster called a

Gorgon is uncertain. The nameless horror may be the head of

either man or beast, or monster compounded of both.

In literature the Gorgon first meets us

as a Gorgoneion, and this Gorgoneion is an underworld bogey.

Odysseus in Hades would fain have held further converse with dead

heroes, but Homer is quite non-committal as to who and what the

awful monster is; all that is clear is that the head only is

feared as an atrorpotraiov, a bogey to

keep you off. Whether he knew of an actual monster called a

Gorgon is uncertain. The nameless horror may be the head of

either man or beast, or monster compounded of both.

In this connection it is instructive to note that, though the human Medusa-head on the whole obtained, the head of any beast is good as a protective charm. Prof. Ridge way has conclusively shown that the Gorgoneion on the aegis of Athene is but the head of the slain beast whose skin was the raiment of the primitive goddess; the head is worn on the breast, and serves to protect the wearer and to frighten his foe; it is a primitive half-magical shield. The natural head is later tricked out into an artificial bogey.

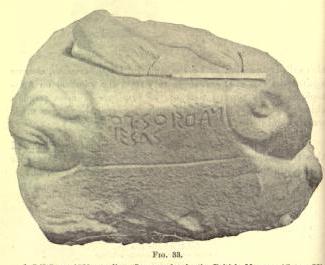

We are familiar with the Gorgoneion on shields, with the Gorgoneion on tombs, and as an amulet on vases. On the basis in fig. 33 the Gorgoneion is set to guard a statue of which two delicate feet remain. On two sides of the triangular statue we have the Gorgon head; on the third, serving a like protective purpose, a ram's head. The statue, dedicated in the precinct of Apollo at Delos, probably represents the god himself, but we need seek for no artificial connection between Gorgon, rams and Apollo; Gorgoneion and ram alike are merely prophylactic. The basis has a further interest in that the inscription dates the Gorgon-type represented with some precision. The form of the letters shows it to have been the work and the dedication of a Naxian artist of the early part of the 6th century.

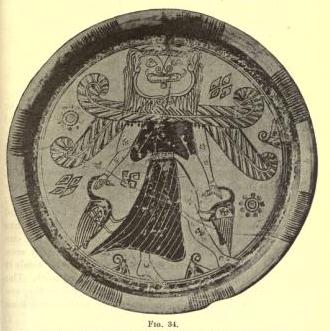

On a Rhodian plate in the British Museum in fig. 34 the Gorgoneion has been furnished with a body tricked out with wings, but the mask-head is still dominant. The figure is conceived in the typical heraldic fashion of the Mistress of Wild Things; she is in fact the ugly bogey, Erinys-side of the Great Mother; she is a potent goddess, not as in later days a monster to be slain by heroes. The highest divinities of the religion of fear and riddance became the harmful bogeys of the cult of 'service.' The Olympians in their turn became Christian devils.

Aeschylus in instructive fashion places side by side the two sets of three sisters, the Gorgons and the Graiae. They are but two by-forms of each other. Prometheus foretells to lo her long wandering in the bogey land of Nowhere:

'Pass onward o'er the sounding sea, till thou

Dost touch Kisthene's dreadful plains, wherein

The Phorkides do dwell, the ancient maids,

Three, shaped like swans, having one eye for all,

One tooth whom never doth the rising sun

Glad with his beams, nor yet the moon by night

Near them their sisters three, the Gorgons, winged,

With snakes for hair hated of mortal man

None may behold and bear their breathing blight.'

The daughters of Phorkys, whom Hesiod calls Grey Ones or Old Ones, Graiae, are fair of face though two-thirds blind and one-toothed; but the emphasis on the one tooth and the one eye shows that in tooth and eye resided their potency, and that in this they were own sisters to the Gorgons.

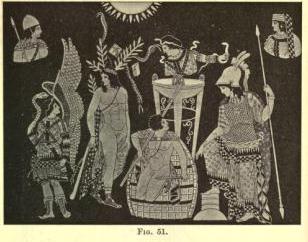

The Graiae appear, so far as I

know, only once in vase-paintings, on the cover of a pyxis in the

Central Museum at Athens, reproduced in fig. 35.

The Graiae appear, so far as I

know, only once in vase-paintings, on the cover of a pyxis in the

Central Museum at Athens, reproduced in fig. 35.

They are sea-maidens, as the dolphins show; old Phorkys their father is seated near them, and Poseidon and Athene are present in regular Athenian fashion. Hermes has brought Perseus, and Perseus waits his chance to get the one eye as it is passed from hand to hand.

The eye is clearly seen in the hand outstretched above Perseus; one blind sister hands it to the other. The third holds in her hand the fanged tooth.

The vase-painter will not have the Graiae old and loathsome, they are lovely maidens; he remembers that they were white-haired from their youth.

The account given by Aeschylus of the Gorgons helps to explain their nature:

'None may behold, and bear their breathing blight.'

They slay by a malign effluence, and this effluence, tradition said, came from their eyes. Athenaeus quotes Alexander the Myndian as his authority for the statement that there actually existed creatures who could by their eyes turn men to stone.

Some say the beast which the Libyans called Gorgon was like a wild sheep, others like a calf; it had a mane hanging over its eyes so heavy that it could only shake it aside with difficulty; it killed whomever it looked at, not by its breath but by a destructive exhalation from its eyes.

What the beast was and how the story arose cannot be decided, but it is clear that the Gorgon was regarded as a sort of incarnate Evil Eye. The monster was tricked out with cruel tusks and snakes, but it slew by the eye, it fascinated.

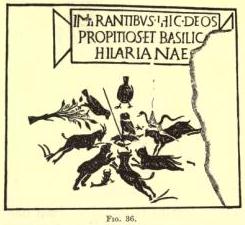

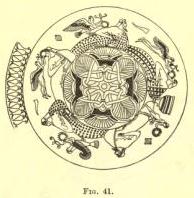

The Evil Eye itself is not frequent

on monuments; the Gorgoneion as a more complete and more

elaborately decorative horror attained a wider popularity. But

the prophylactic Eye, the eye set to stare back the Evil Eye, is

common on vases, on shields and on the prows of ships (see fig.

38). The curious design in fig. 36 is from a Roman mosaic dug up

on the Caelian hill. It served as the pavement in an entrance

hall to a Basilica built by a certain Hilarius, a dealer in

pearls (margaritarius) and head of a college of Dendrophoroi,

sacred to the Mother of the Gods. The inscription prays that'God

may be propitious to those who enter here and to the Basilica of

Hilarius,'and to make divine favour more secure, a picture is

added to show the complete overthrow of the evil eye. Very

complete is its destruction. Fourfooted beasts, birds and

reptiles attack it, it is bored through with a lance, and as a

final prophylactic on the eye-brow is perched Athene's little

holy owl. Hilarius prayed to a kindly god, but deep down in his

heart was the old savage fear.

The Evil Eye itself is not frequent

on monuments; the Gorgoneion as a more complete and more

elaborately decorative horror attained a wider popularity. But

the prophylactic Eye, the eye set to stare back the Evil Eye, is

common on vases, on shields and on the prows of ships (see fig.

38). The curious design in fig. 36 is from a Roman mosaic dug up

on the Caelian hill. It served as the pavement in an entrance

hall to a Basilica built by a certain Hilarius, a dealer in

pearls (margaritarius) and head of a college of Dendrophoroi,

sacred to the Mother of the Gods. The inscription prays that'God

may be propitious to those who enter here and to the Basilica of

Hilarius,'and to make divine favour more secure, a picture is

added to show the complete overthrow of the evil eye. Very

complete is its destruction. Fourfooted beasts, birds and

reptiles attack it, it is bored through with a lance, and as a

final prophylactic on the eye-brow is perched Athene's little

holy owl. Hilarius prayed to a kindly god, but deep down in his

heart was the old savage fear.

The Gorgon is more monstrous, more savage, than any other of the Ker-forms. The Gorgoneion figures little in poetry though much in art.'It is an underworld bogey but not human enough to be a ghost, it lacks wholly the gentle side of the Keres, and would scarcely have been discussed here, but that the art-type of the Gorgon lent, as will be seen, some of its traits to the Erinys, and notably the deathly distillation by which they slay:

'From out their eyes they ooze a loathly rheum.'

The Ker as Siren

The Sirens are to the modern mind mermaids, sometimes all human, sometimes fish-tailed, evil sometimes, but beautiful always. Milton invokes Sabrina from the waves by

'. . .the songs of Sirens sweet,

By dead Parthenope's dear tomb,

And fair Ligeia's golden comb

Wherewith she sits on diamond rocks

Sleeking her soft alluring locks.'

Homer by the magic of his song lifted them once and for all out of the region of mere bogeydom, and yet a careful examination, especially of their art form, clearly reveals traces of rude origin.

Circe's warning to Odysseus runs thus:

'First to the Sirens shalt thou sail, who all men do beguile.

Whoso unwitting draws anigh, by magic of their wile,

They lure him with their singing, nor doth he reach his home

Nor see his dear wife and his babes, ajoy that he is come.

For they, the Sirens, lull him with murmur of sweet sound

Crouching within the meadow: about them is a mound

Of men that rot in death, their skin wasting the bones around.'

Odysseus and his comrades, so forewarned, set sail:

'Then straightway sailed the goodly ship and swift the Sirens'isle

Did reach, for that a friendly gale was blowing all the while.

Forthwith the gale fell dead, and calm held all the heaving deep

In stillness, for some god had lulled the billows to their sleep.'

The song of the Sirens is heard:

'Hither, far-famed Odysseus, come hither, thou the boast

Of all Achaean men, beach thou thy bark upon our coast,

And hearken to our singing, for never but did stay

A hero in his black ship and listened to the lay

Of our sweet lips; full many a thing he knew and sailed away.

For we know all things whatsoe'er in Troy's wide land had birth

And we know all things that shall be upon the fruitful earth.'

It is strange and beautiful that Homer should make the Sirens appeal to the spirit, not to the flesh. To primitive man, Greek or Semite, the desire to know to be as the gods was the fatal desire.

Homer takes his Sirens as already familiar; he clearly draws from popular tradition. There is no word as to their form, no hint of parentage: he does not mean them to be mysterious, but by a fortunate chance he leaves them shrouded in mystery, the mystery of the hidden spell of the sea, with the haze of the noontide about them and the meshes of sweet music for their unseen toils, knowing all things yet for ever unknown. It is this mystery of the Sirens that has appealed to modern poetry and almost wholly obscured their simple primitive significance.

'Their words are no more heard aright

Through lapse of many ages, and no man

Can any more across the waters wan

Behold these singing women of the sea.'

Four points in the story of Homer must be clearly noted. The Sirens, though they sing to mariners, are not sea-maidens; they dwell on an island in a flowery meadow. They are mantic creatures like the Sphinx with whom they have much in common, knowing both the past and the future. Their song takes effect at midday, in a windless calm. The end of that song is death. It is only from the warning of Circe that we know of the heap of bones, corrupt in death horror is kept in the background, seduction to the fore.

It is to art we must turn to know the real nature of the Sirens. Ancient art, like ancient literature, knows nothing of the fish-tailed mermaid. Uniformly the art-form of the Siren is that of the bird-woman. The proportion of bird to woman varies, but the bird element is constant. It is interesting to note that, though the bird-woman is gradually ousted in modern art by the fish-tailed rnermaid, the bird element survives in mediaeval times. In the Hortus Deliciarum of the Abbess Herrad (circ. A.D. 1160), the Sirens appear as draped women with the clawed feet of birds; with their human hands they are playing on lyres.

The bird form of the Sirens was a problem even to the ancients. Ovid asks:

'Whence came these feathers and these feet of birds?

Your faces are the faces of fair maids.'

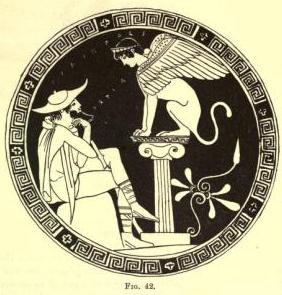

Ovid's aetiology is of course beside the mark. The answer to his pertinent question is quite simple. The Sirens belong to the same order of bogey beings as the Sphinx and the Harpy; the monstrous form expresses the monstrous nature; they are birds of prey but with power to lure by their song. In the Harpy-form the ravening snatching nature is emphasized and developed, in the Sphinx the mantic power of all uncanny beings, in the Siren the seduction of song. The Sphinx, though mainly a prophetess, keeps Harpy elements; she snatches away the youths of Thebes: she is but 'a man-seizing Ker.' The Siren too, though mainly a seductive singer, is at heart a Harpy, a bird of prey.

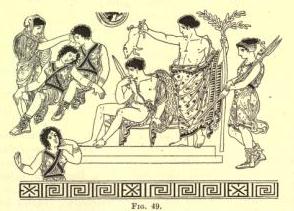

This comes out very clearly in

representations on vase-paintings.

This comes out very clearly in

representations on vase-paintings.

A black-figured aryballos of Corinthian style (fig. 37), now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, is our earliest artistic source for the Siren myth. Odysseus, bound to the mast, has come close up to the island: on the island are perched'Sirens twain.'Above the ship hover two great black birds of prey in act to pounce on the mariners. These birds cannot be merely decorative: they in a sense duplicate the Sirens.

The vase-painter knows the Sirens are singing demons sitting on an island; the text of Homer was not in his hands to examine the account word by word, but the Homeric story haunts his memory. He knows too that in popular belief the Sirens are demons of prey; hence the great birds. To the right of the Sirens on the island crouches a third figure; she is all human, not a third Siren. She probably, indeed all but certainly, represents the mother of the Sirens, Chthon, the Earth. Euripides makes his Helen in her anguish call on the

'Winged maidens, virgins, daughters of the Earth,

The Sirens,'

to join their sorrowful song to hers. The parentage is significant. The Sirens are not of the sea, not even of the land, but demons of the underworld; they are in fact a by-form of Keres, souls.

The notion of the soul as a human-faced bird is familiar in Egyptian, but rare in Greek, art. The only certain instance is, so far as I know, the vase in the British Museum on which is represented the death of Procris. Above Procris falling in death hovers a winged bird-woman. She is clearly, I think, the soul of Procris. To conceive of the soul as a bird escaping from the mouth is a fancy so natural and beautiful that it has arisen among many peoples. In Celtic mythology Maildun, the Irish Odysseus, comes to an island with trees on it in clusters on which were perched many birds. The aged man of the island tells him,'These are the souls of my children and of all my descendants, both men and women, who are sent to this little island to abide with me according as they die in Erin.' Sailors to this day believe that sea-mews are the souls of their drowned comrades. Antoninus Liberalis tells how, when Ktesulla because of her father's broken oath died in child-bed, 'they carried her body out to be buried, and from the bier a dove flew forth and the body of Ktesulla disappeared.'

The persistent anthropomorphism of the Greeks stripped the bird-soul of all but its wings. The human winged eidolon prevailed in art: the bird-woman became a death-demon, a soul sent to fetch a soul, a Ker that lures a soul, a Siren.

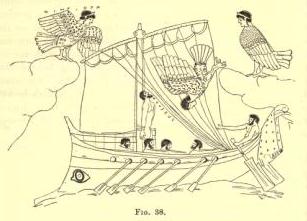

Later in date and somewhat

different in conception is the scene on a red-figured stamnos in

the British Museum (fig. 38). The artist's desire for a balanced

design has made him draw two islands, on each of which a Siren is

perched. Over the head of one is inscribed 'lovely-voiced.'

Later in date and somewhat

different in conception is the scene on a red-figured stamnos in

the British Museum (fig. 38). The artist's desire for a balanced

design has made him draw two islands, on each of which a Siren is

perched. Over the head of one is inscribed 'lovely-voiced.'

A third Siren flies or rather falls headlong down on to the ship. The drawing of the eye of this third Siren should be noted. The eye is indicated by two strokes only, without the pupil. This is the regular method of representing the sightless eye, i.e. the eye in death or sleep or blindness. The third Siren is dying; she has hurled herself from the rock in despair at the fortitude of Odysseus. This is clearly what the artist wishes to say, but he may have been haunted by an artistic tradition of the pouncing bird of prey. He also has adopted the number three, which by his time was canonical for the Sirens. By making the third Siren fly headlong between the two others he has neatly turned a difficulty in composition. On the reverse of this vase are three Love-gods, who fall to be discussed later. Connections between the subject matter of the obverse and reverse of vases are somewhat precarious, but it is likely, as the three Love-gods are flying over the sea, that the vase-painter intended to emphasize the seduction of love in his Sirens.

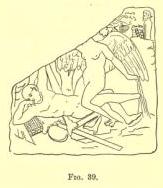

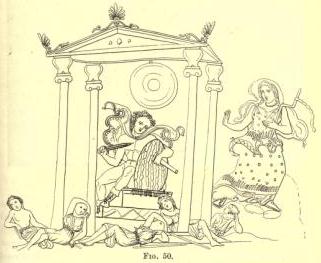

The clearest light on the lower nature

of the Sirens is thrown by the design in fig. 39 from a

Hellenistic relief. The monument is of course a late one, later

by at least two centuries than the vase-paintings, but it

reflects a primitive stage of thought and one moreover wholly

free from the influence of Homer. The scene is a rural one. In

the right-hand corner is a herm, in front of it an altar, near at

hand a tree on which hangs a votive syrinx. Some peasant or

possibly a wayfarer has fallen asleep.

The clearest light on the lower nature

of the Sirens is thrown by the design in fig. 39 from a

Hellenistic relief. The monument is of course a late one, later

by at least two centuries than the vase-paintings, but it

reflects a primitive stage of thought and one moreover wholly

free from the influence of Homer. The scene is a rural one. In

the right-hand corner is a herm, in front of it an altar, near at

hand a tree on which hangs a votive syrinx. Some peasant or

possibly a wayfarer has fallen asleep.

Down upon him has pounced a winged and bird-footed woman. It is the very image of obsession, of nightmare, of a haunting midday dream.

The woman can be none other than an evil Siren. Had the scene been represented by an earlier artist, he would have made her ugly because evil; but by Hellenistic times the Sirens were beautiful women, all human but for wings and sometimes bird-feet.

The terrors of the midday sleep were well known to the Greeks in their sun-smitten land; nightmare to them was also daymare. Such a visitation, coupled possibly with occasional cases of sunstroke, was of course the obsession of a demon. Even a troubled tormenting illicit dream was the work of a Siren. In sleep the will and the reason are becalmed and the passions unchained. That the midday nightmare went to the making of the Siren is clear from the windless calm and the heat of the sun in Homer. The horrid end, the wasting death, the sterile enchantment, the loss of wife and babes, all look the same way. Homer, with perhaps some blend of the Northern mermaid in his mind, sets his Sirens by the sea, thereby cleansing their uncleanness; but later tradition kept certain horrid primitive elements when it made of the Siren a Jietaira disallowing the lawful gifts of Aphrodite.

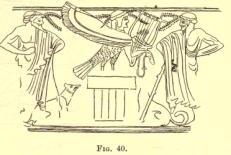

There remains another aspect of the Sirens. They appear frequently as monuments, sometimes as actual mourners, on tombs. Here all the erotic element has disappeared; they are substantially Death-Keres, Harpies, though to begin with they imaged the soul itself. The bird-woman of the Harpy tomb, the gentle angel of death, has been already noted. The Siren on a black-figured lekythos in the British Museum (fig. 40) is purely monumental.

She stands on the grave stele playing

her great lyre, while two bearded men with their dogs seem to

listen intent. She is grave and beautiful with no touch of

seduction. Probably at first the Siren was placed on tombs as a

sort of charm, a Trpoftao-Kaviov, a soul to keep off souls. It

has already been shown, in dealing with apotropaic ritual, that

the charm itself is used as countercharm. So the dreaded

Death-Ker is set itself to guard the tomb. Other associations

would gather round. The Siren was a singer, she would chant the

funeral dirge; this dirge might be the praises of the dead. The

epitaph that Erinna wrote for her girlfriend Baukis begins

She stands on the grave stele playing

her great lyre, while two bearded men with their dogs seem to

listen intent. She is grave and beautiful with no touch of

seduction. Probably at first the Siren was placed on tombs as a

sort of charm, a Trpoftao-Kaviov, a soul to keep off souls. It

has already been shown, in dealing with apotropaic ritual, that

the charm itself is used as countercharm. So the dreaded

Death-Ker is set itself to guard the tomb. Other associations

would gather round. The Siren was a singer, she would chant the

funeral dirge; this dirge might be the praises of the dead. The

epitaph that Erinna wrote for her girlfriend Baukis begins

Pillars and Sirens mine and mournful urn.'

On later funeral monuments Sirens appear for the most part as mourners, tearing their hair and lamenting. Their apotropaic function was wholly forgotten. Where an apotropaic monster is wanted we find an owl or a sphinx.

Even on funeral monuments the notion of the Siren as either soul or Death-Angel is more and more obscured by her potency as sweet singer. Once, however, when she appears in philosophy, there is at least a haunting remembrance that she is a soul who sings to souls. In the cosmography with which he ends the Republic, Plato thus writes:

'The spindle turns on the knees of Ananke, and on the upper surface of each sphere is perched a Siren, who goes round with them hymning a single tone. The eight together form one Harmony.'

Commentators explain that the Sirens are chosen because they are sweet singers, but then, if music be all, why is it the evil Sirens and not the good Muses who chant the music of the spheres? Plutarch felt the difficulty. In his Symposiacs he makes one of the guests say:

'Plato is absurd in committing the eternal and divine revolutions not to the Muses but to the Sirens; demons who are by no means either benevolent or in themselves good.'

Another guest, Ammonius, attempts to justify the choice of the Sirens by giving to them in Homer a mystical significance.

'Even Homer,'he says, 'means by their music not a power dangerous and destructive to man, but rather a power that inspires in the souls that go from Hence Thither, and wander about after death, a love for things heavenly and divine and a forgetfulness of things mortal, and thereby holds them enchanted by singing. Even here he goes on to say,'a dim murmur of that music reaches us, rousing reminiscence.'

It is not to be for a moment supposed that Homer's Sirens had really any such mystical content. But, given that they have the bird-form of souls, that they'know all things, 'are sweet singers and dwellers in Hades, and they lie ready to the hand of the mystic. Proclus in his commentary on the Republic says, with perhaps more truth than he is conscious of,

'the Sirens are a kind of souls living the life of the spirit.'

His interpretation is not merely fanciful; it is a blend of primitive tradition with mystical philosophy.

The Sirens are further helped to their high station on the spheres by the Orphic belief that purified souls went to the stars, nay even became stars. In the Peace of Aristophanes 4 the servant asks Trygaeus,

'It is true then, what they say, that in the air A man becomes a star, when he comes to die?'

To the poet the soul is a bird in its longing to be free:

'Could I take me to some cavern for mine hiding,

On the hill-tops, where the sun scarce hath trod,

Or a cloud make the place of mine abiding,