|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER VI.

THE MAKING OF A GODDESS.

Anthropomorphism | The Mother and the Maid | The Lady of the Wild Things | The Mother as Kourotrophos | Demeter and Kor | The Anodos of the Maiden | Pandora | The Maiden-Trinities | The Judgment of Paris | Athene | Aphrodite | Hera

IN the last chapter we have traced the development from Keres to Erinyes, and have seen that, on the whole, this development was a downward course. The Erinyes are in a sense more civilized than the Keres; they are beings more articulate, more clearly outlined and concerned with issues moral rather than physical; but the career they start as angry souls they end as Poinae, ministers of vindictive torment; there is in them no element of hope, no kindly impulse towards purification, they end where they began as irreconcileable demons rather than friendly gods.

We have further marked the attempt of Aeschylus to turn the vindictive demons of the old religion into the gentler divinities of the new, and we have seen that, for all his genius, the attempt failed wholly. The Erinyes never, save here and there to a puzzled antiquarian, became really Semnae; the popular instinct of their utter distinctness remained sound. We have now to note that, where the genius of a poet fails, the slow-moving widespread instinct of a people may prevail; ghosts are not wholly angry, and the gentler form of ghost may and does become a god.

The line between a spirit (saipatv) and a regular god (teos) is drawn with no marked precision. The difference is best realized by remembering the old principle that man makes all the objects of his worship in his own image. Before he has himself clearly realized his own humanity the line that marks him off from other animals, he makes his divinities sometimes wholly animal, sometimes of mixed, monstrous shapes. His animal-shaped gods the Greek quickly outgrew; something will be said of them when we come to the religion of the Bull-Dionysos. Mixed monstrous shapes long haunted his imagination; bird-woman-souls, Gorgon-bogeys, Sphinxes, Harpies and the like were, as has been seen, the fitting vehicles of a religion that was mainly of vague fear. But as man became more conscious of his humanity and pari passu grew more humane, a more complete anthropomorphism steadily prevailed, and in the figures of wholly human gods man mirrored his gentler affections, his advance in the ordered relations of life.

Xenophanes, writing in the 6th century B.C., knew that God is 'without body, parts or passions,' but he knew also that, till man becomes wholly philosopher, his gods are doomed perennially to take and retake human shape. His thrice-familiar words still bear repetition:

'One God there is greatest of gods and mortals;

Not like to man is he in mind or body.

All of him sees, all of him thinks and hearkens.....

But mortal man made gods in his own image

Like to himself in vesture, voice and body.

Had they but hands, methinks, oxen and lions

And horses would have made them gods like-fashioned,

Horse-gods for horses, oxen-gods for oxen.'

We are apt to regard the advance to anthropomorphism as necessarily a clear religious gain. A gain it is in so far as a certain element of barbarity is softened or extruded, but with this gain comes loss, the loss of the element of formless, monstrous mystery. The ram-headed Knum of the Egyptians is to the mystic more religious than any of the beautiful divine humanities of the Greek. Anthropomorphism provides a store of lovely motives for art, but that spirit is scarcely religious which makes of Eros a boy trundling a hoop, of Apollo a youth aiming a stone at a lizard, of Nike a woman who stoops to tie her sandal. Xenophanes put his finger on the weak spot of anthropomorphism. He saw that it comprised and confined the god within the limitations of the worshipper. It is not every religion that advances as far as anthropomorphism, but the farthest of anthropomorphism is not very far.

Anthropomorphism

Traces of animal form are among the recognized Greek gods few and scattered. Pausanias heard at Phigaleia of a horse-headed Demeter, and again of a fish-bodied Eurynome whom some called Artemis, but for the most part by the 6th and 5th centuries B.C. mixed forms, half animal, half human, belong to beings half-way between man and god, demons rather than full-fledged divinities and demons malignant rather than beneficent. Such are Boreas, Echidna, Typhon and the snake-tailed giants.

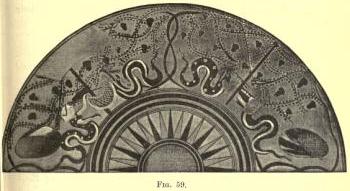

In the design from a black-figured

cylix in fig. 59 we have a curious and rare instance of beings of

monstrous form, yet obviously beneficent. The scene is a vineyard

at the time of vintage. On the reverse (not figured here) we have

the same vintage-setting, but goats, the destroyers of the vine,

are nibbling at the vine-stems. On the obverse (fig. 59) we have

snake-bodied nymphs rejoicing in the grape harvest. Two of them

hold a basket of net or wicker in which the grapes will be

gathered, a third holds a great cup for the vine-juice, a fourth

plays on the double flutes. Unhappily we can give no certain name

to these kindly grape-gathering, flute-playing snake-nymphs. They

are copai, but assuredly they are not Erinyes and we dare not

even call them Eumenides. Probably any Athenian child would have

named them without a moment's hesitation, but we must be content

to say that, in their essence, they are Charites, givers of grace

and increase, and that their snake-bodies mark them not as

malevolent, but as earth-daemons, genii of fertility. They are

near akin to the local Athenian hero, the snake-tailed Cecrops,

and we are tempted to conjecture that in art, though not in

literature, he may have lent his snake-tail to the Agraulid

nymphs, his daughters. Later it will be seen that earth-born

goddesses, though they shed their snake-form, keep as their

vehicle and attribute the snake they once were.

In the design from a black-figured

cylix in fig. 59 we have a curious and rare instance of beings of

monstrous form, yet obviously beneficent. The scene is a vineyard

at the time of vintage. On the reverse (not figured here) we have

the same vintage-setting, but goats, the destroyers of the vine,

are nibbling at the vine-stems. On the obverse (fig. 59) we have

snake-bodied nymphs rejoicing in the grape harvest. Two of them

hold a basket of net or wicker in which the grapes will be

gathered, a third holds a great cup for the vine-juice, a fourth

plays on the double flutes. Unhappily we can give no certain name

to these kindly grape-gathering, flute-playing snake-nymphs. They

are copai, but assuredly they are not Erinyes and we dare not

even call them Eumenides. Probably any Athenian child would have

named them without a moment's hesitation, but we must be content

to say that, in their essence, they are Charites, givers of grace

and increase, and that their snake-bodies mark them not as

malevolent, but as earth-daemons, genii of fertility. They are

near akin to the local Athenian hero, the snake-tailed Cecrops,

and we are tempted to conjecture that in art, though not in

literature, he may have lent his snake-tail to the Agraulid

nymphs, his daughters. Later it will be seen that earth-born

goddesses, though they shed their snake-form, keep as their

vehicle and attribute the snake they once were.

The Mother and the Maid

The gods reflect not only man's human form but also his human relations. In the Homeric Olympus we see mirrored a family group of the ordinary patriarchal type, a type so familiar that it scarcely arrests attention. Zeus, Father of Gods and men, is supreme; Hera, though in constant and significant revolt, occupies the subordinate place of a wife; Poseidon is a younger brother, and the rest of the Olympians are grouped about Zeus and Hera in the relation of sons and daughters. These sons and daughters are quarrelsome among themselves and in constant insurrection against father and mother, but still they constitute a family, and a family subject, if reluctantly, to the final authority of a father.

But when we come to examine local cults we find that, if these mirror the civilization of the worshippers, this civilization is quite other than patriarchal. Hera, subject in the Homeric Olympus, reigns alone at Argos; Athene at Athens is no god's wife, she is affiliated in some loose fashion to Poseidon, but the relation is one of rivalry and ultimate conquest, nowise of subordination. At Eleusis two goddesses reign supreme, Demeter and Kore, the Mother and the Maid; neither Hades nor Triptolemos their nursling ever disputes their sway. At Delphi in historical days Apollo held the oracle, but Apollo, the priestess knows, was preceded by a succession of women goddesses:

'First in my prayer before all other gods

I call on Earth, primaeval prophetess.

Next Themis on her mother's oracular seat

Sat, so men say. Third by unforced consent

Another Titan, daughter too of Earth,

Phoebe. She gave it as a birthday gift

To Phoebus, and giving called it by her name.'

Gaia the Earth was first, and elsewhere Aeschylus tells us that Themis was but another name of Gaia. Prometheus says the future was foretold him by his mother:

'Themis she

And Gaia, one in form with many names.'

In historical days in Greece, descent was for the most part traced through the father. These primitive goddesses reflect another condition of things, a relationship traced through the mother, the state of society known by the awkward term matriarchal, a state echoed in the lost Catalogues of Women, the Eoiai of Hesiod, and in the Boeotian heroines of the Nekuia. Our modern patriarchal society focusses its religious anthropomorphism on the relationship of the father and the son; the Roman Church with her wider humanity includes indeed the figure of the Mother who is both Mother and Maid, but she is still in some sense subordinate to the Father and the Son.

Of the many survivals of matriarchal notions in Greek mythology one salient instance may be noted. St Augustine, telling the story of the rivalry between Athene and Poseidon, says that the contest was decided by the vote of the citizens, both men and women, for it was the custom then for women to take part in public affairs. The men voted for Poseidon, the women for Athene; the women exceeded the men by one and Athene prevailed. To appease the wrath of Poseidon the men inflicted on the women a triple punishment,'they were to lose their vote, their children were no longer to be called by their mothers name and they themselves were no longer to be called after their goddess, Athenians.'

The myth is aetiological, and it mirrors surely some shift in the social organization of Athens. The citizens were summoned by Cecrops, and it is noticeable that with his name universal tradition associates the introduction of the patriarchal form of marriage. Athenaeus quoting from Clearchos, the pupil of Aristotle, says,'At Athens Cecrops was the first to join one woman to one man: before connections had taken place at random and marriages were in common hence, as some think, Cecrops was called " Twy-formed ", since before his day people did not know who their fathers were, on account of the number (of possible parents).' A society that had passed to patriarchy naturally misjudged the marriage-laws of matriarchy and regarded it as a mere state of promiscuity. Cecrops, tradition said, was the first to call Zeus the Highest, and with the worship of Zeus the Father it is possible that he introduced the social conditions of patriarchy. Apollo, the son of Zeus, was worshipped at Athens as Patroos.

The primitive Greek was of course not conscious that he mirrored his own human relations in the figures of his gods, but, in the reflective days of Pythagoras, the analogy between human and divine was not left unnoted. The evidence he adduces as to the piety of women is perhaps the most illuminating comment on primitive theology ever made by ancient or modern.'Women,' he 3 says,'give to each successive stage of their life the same name as a god, they call the unmarried woman Maiden (K6prj\ the woman given in marriage to a man Bride, her who has borne children Mother, and her who has borne children's children Grandmother.' Invert the statement and we have the whole matriarchal theology in a nutshell. The matriarchal goddesses reflect the life of women, not women the life of the goddesses.

Of these various forms of the conditions of woman, woman as maiden, bride, mother and grandmother, the last, grandmother comes little into prominence; it only lends a name to Maia, the mother of Hermes. Nymphs we have everywhere, but the two cardinal conditions are obviously to a primitive society Mother and Maiden. When these conditions crystallized into the goddess forms of Demeter and Kore, they appear as Mother and Daughter, but primarily the conditions expressed are Mother and Maid, woman mature and woman before maturity, and of these two forms the Mother-form as more characteristic is, in early days, the more prominent; Kore as daughter rather than maiden is the product of mythology. When we come to the religion of Dionysos, it will be seen that the Mother-goddess has for her attribute of motherhood a son rather than a daughter.

The Earth Mother As Karpophorus Or

The Lady of the Wild Things

The Mother-goddess was almost necessarily envisaged as the Earth. The ancient Dove-priestesses at Dodona were the first to chant the Litany:

'Zeus was, Zeus is, Zeus shall be, great Zeus.

Earth sends up fruits, so praise we Earth the Mother.

The two lines have no necessary connection; it may be that their order is inverted and that long before the Dove-priestesses sang the praises of Zeus they had chanted their hymn to the Mother. It was fitting that women priestesses should sing to a woman goddess, to Ga who was also Ma. Mother-Earth bore not only fruits but the race of man. As the poet Asiussaid:

'Divine Pelasgos on the wood-clad hills

Black Earth brought forth, that mortal man might be.'

Pelasgos claimed no father, but he, the first father, had a mother. And here it must be noted that the local mother must necessarily have preceded Gaia the abstract and universal. Primitive man does not tend to deal in abstractions. Each local hero claimed descent from a local earth-nymph or mother. Salamis, Aegina and'dear mother Ida'are not late geographical abstractions; each is a local mother, a real parent, and all are later merged in the great All-Mother Ge.

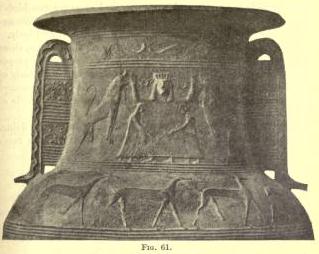

The Earth-Mother and each and every local nymph was mother not only of man but of all creatures that live; she is the 'Lady of the Wild Things'. Art brings her figure very clearly before us. On an early stamped Boeotian amphora in the National Museum at Athens (figs. 60 and 61) she is vividly presented.

The Great Mother stands with uplifted hands exactly in the attitude of the still earlier figures recently discovered in the Mycenaean shrine at Cnossos. To either side of her is a lion, heraldically posed like the lions of the Gate at Mycenae; below her is a frieze of deer. The figure is supported or rather encircled by two women figures, one at either side. These seem to be part of a ring of encircling worshippers.

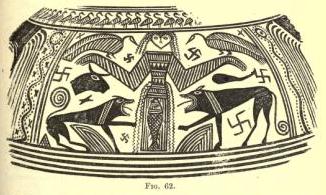

The design in fig. 62 from a painted Boeotian amphora, also in the Museum at Athens, shows a similar and even more complete conception of the 'Lady of the Wild Things.' Her two lions still keep heraldic guard, above her outstretched arms are two birds, her gown is decorated with the figure of a great fish. We are reminded of the Eurynome of Phigalia with her fish-tailed body.

The interesting thing about these early representations, these and countless others, is that we can give the goddess no proper name.

We call her rightly the Great Mother and the 'Lady of the Wild Things' but farther we cannot go. She has been named Artemis and Cybele, but for neither name is there a particle of evidence.

The Great Mother is mother of the

dead as well as the living. The design in fig. 63 is from the

interior of a rock-hewn tomb in Phrygia. The great figure of the

Mother and her lions occupies the whole height of the back wall

of the tomb. 'All things' as Cicero says, 'go back to earth and

rise out of the earth.'

The Great Mother is mother of the

dead as well as the living. The design in fig. 63 is from the

interior of a rock-hewn tomb in Phrygia. The great figure of the

Mother and her lions occupies the whole height of the back wall

of the tomb. 'All things' as Cicero says, 'go back to earth and

rise out of the earth.'

'Dust we are, and unto dust we shall return' and more tenderly Aeschylus:

'Yea, summon Earth, who brings all things to life

And rears and takes again into her womb.'

And so the Mother herself keeps ward in the metropolis of the dead, and therefore'the Athenians of old called the dead "Demeter's people".'On the festival day of the dead, the Nekusia at Athens, they sacrificed to Earth. To a people who practised inhumation, such ritual and such symbolism were almost inevitable. When the Earth-Mother developed into the Corn-Mother, such symbolism gained new life and force from the processes of agriculture. Cicero records that in his day it was still the custom to sow the graves of the dead with corn: 'that which thou sowest is not quickened except it die.' Out of the symbolism of the corn sown the Greeks did not develope a doctrine of immortality, but, when that doctrine came to them from without, the symbolism of the seed lay ready to hand.

The Mother as Kourotrophos

Early art figures the Mother in quaint

instructive fashion as Kourotrophos, the Child-Rearer. As such

she appears in the design in fig. 64 taken from an early

black-figured amphora of the 6th century B.C. in the British

Museum . This figure of the Mother is usually explained as Leto

with the twins Apollo and Artemis, but such an interpretation is,

I think, over-bold, and really misleading. The artist knows that

there is a Mother-Goddess; one child would be sufficient as an

attribute of motherhood, but in his quaint primitive fashion he

wishes to emphasise her motherhood, he gives her all the children

she can conveniently hold, one on each shoulder.

Early art figures the Mother in quaint

instructive fashion as Kourotrophos, the Child-Rearer. As such

she appears in the design in fig. 64 taken from an early

black-figured amphora of the 6th century B.C. in the British

Museum . This figure of the Mother is usually explained as Leto

with the twins Apollo and Artemis, but such an interpretation is,

I think, over-bold, and really misleading. The artist knows that

there is a Mother-Goddess; one child would be sufficient as an

attribute of motherhood, but in his quaint primitive fashion he

wishes to emphasise her motherhood, he gives her all the children

she can conveniently hold, one on each shoulder.

We have no right to name the children Apollo and Artemis, unless inscribed or marked as such by attributes. This is clear from the fact that, on a fragment of a vase found in the Acropolis excavations and unhappily still unpublished, we have a figure closely analogous, though later in style, to our Kourotrophos, bearing on her elbows two little naked imps who are inscribed: the one is Himeros, the other E(ros). The mother can in this case be none other than Aphrodite. The attribution is confirmed by another fragmen in which only half of the Mother-goddess is preserved and one child seated on her elbow; the child is not inscribed, but against the mother, in archaic letters, is written Aphrodi(te); near her as on our vase is standing Dionysos.

Pausanias , when examining the chest of Cypselos, saw a design on which was represented 'a woman carrying a white boy sleeping on her right arm; on the other arm she has a black boy who is like the one who is asleep; they both have their feet twisted; the inscriptions show that the boys are Death and Sleep, and that Night is the nurse of both.' He adds the rather surprising statement that it 'would have been easy to see who they were without the inscriptions.'

A woman with a child on each arm can then represent Aphrodite with Himeros and Eros; if one child is white and asleep and the other black, the group represents Night with Death and Sleep; if the group is to represent Leto and her twins, there must be something to mark the twins as Apollo and Artemis. On another amphora in the British Museum there does exist just the necessary differentiation: the child on the left arm is naked, the child on the right though also painted black wears a short chiton. We are justified in supposing that the one is a boy the other a girl, and there is at least a high probability that the differentiation of sex points to Apollo and Artemis.

I have dwelt on this point because vase-paintings are here, as so often, highly instructive in the matter of the development and slow differentiation and articulation of theological types. At first all is vague and misty; there is, as it were, a blank formula, a mother-goddess characterized by twins. If we give her a name at all she is Kourotrophos. As her personality grows she differentiates, she is Aphrodite with Eros and Himeros, she is Night with Sleep and Death. When Apollo and Artemis came from the North they became the twins par excellence, and they are affiliated to the old religion; the Mother as Kourotrophos became Leto with Apollo and Artemis.

The like process goes on in literature, though it is less obviously manifest. At the opening of the Thesmophoria the Woman-Herald in Aristophanes makes proclamation as follows:

'Keep solemn silence. Keep solemn silence. Pray to the two Thesmophoroi, to Demeter, and to Kore, and to Plouton, and to Kalligeneia, and to Kourotrophos, and to Hermes, and the Charites.'

Discussion from the time of the scholiast onwards has raged as to who Kourotrophos is is she Hestia, is she Ge? The simple truth is never faced that she is Kourotrophos, an attribute become a personality. Her personality, it is true, faded before the dominant personality of the Mother of Eleusis, but her presence in the ancient ritual-formulary speaks clearly for her original actuality. Once she had faded, all the other more successful goddesses, Ge, Artemis, Hekate, Leto, Demeter, Aphrodite, even Athene, contend for her name as their epithet. There is no controversy so idle and apparently so prolific as that which seeks to find in these ancient inchoate personalities, such as Kourotrophos and Kalligeneia, the epithets of the Olympians they so long predated.

The figure of the Mother as Kourotrophos lent itself easily to later abstractions. Themis is one of the earliest, and she attains a real personality; her sisters Eunomia and Dike are scarcely flesh and blood, they are beautiful stately shadows. The 'making of a goddess' is always a mystery, the outcome of manifold causes of which we have lost count. At the close of the 5th century B.C. at the end of the weary, fatal Peloponnesian war, Eirene, Peace, almost attained godhead, and godhead as the Mother. Cephisodotos, father of Praxiteles, made for the market-place at Athens a statue of her carrying the child Ploutos, the Athenians built her an altar and did sacrifice to her, Aristophanes brings her on the stage, but it is all too late and in vain, she remains an abstraction as lifeless as Theoria or Opora, and finds no place among the humanities of Olympus.

Tyche, Fortune, another late

abstraction of the Mother, though she is scarcely more human than

Eirene, obtained a wide popularity. Pausanias saw at Thebes a

sanctuary of Tyche; he remarks after naming the artists, 'it was

a clever plan of them to put Ploutos in the arms of Tyche as his

mother or nurse, and Cephisodotos was no less clever; he made for

the Athenians the image of Eirene holding Ploutos.'

Tyche, Fortune, another late

abstraction of the Mother, though she is scarcely more human than

Eirene, obtained a wide popularity. Pausanias saw at Thebes a

sanctuary of Tyche; he remarks after naming the artists, 'it was

a clever plan of them to put Ploutos in the arms of Tyche as his

mother or nurse, and Cephisodotos was no less clever; he made for

the Athenians the image of Eirene holding Ploutos.'

These abstractions, Tyche, Ananke and the like, were popular with the Orphics. Their very lack of personality favoured a growing philosophic monotheism. The design in fig. 65 is carved in low relief on one of the columns of the Hall of the Mystae of Dionysos, recently excavated at Melos. Tyche holds a child presumably the local Ploutos of Melos in her arms. Above her is inscribed, 'May Agathe Tyche of Melos be gracious to Alexandros, the founder of the holy Mystae.' Tyche, Fortune, might be, to the uninitiated, the Patron, the Good Luck of any and every city, but to the mystic she had another and a deeper meaning; she, like the Agathos Daimon, was the inner Fate of his life and soul. In her house, as will later be seen, he lodged, observing rules of purity and abstinence before he was initiated into the underworld mysteries of Trophonios, before he drank of the waters of Lethe and Mnemosyne. It is one of the countless instances in which the Orphics went back behind the Olympian divinities and mysticized the earlier figures of the Mother or the Daughter.

Demeter and Kor

So long as and wherever man lived for the most part by hunting, the figure of the'Lady of the Wild Things'would content his imagination. But, when he became an agriculturist, the Mother-goddess must perforce be, not only Kourotrophos of all living things, but also the Corn-mother, Demeter.

The derivation of the name Demeter has been often discussed. The most popular etymology is that which makes her Earth-mother, Ga, regarded as the equivalent of Fa. From the point of view of meaning this etymology is nowise satisfactory. Demeter is not the Earth-Mother, not the goddess of the earth in general, but of the fruits of the civilized, cultured earth, the tilth; not the 'Lady of the Wild Things,' but She-who-bears-fruits, Karpophoros. Mannhardt was the first to point out another etymology, more consonant with this notion. The author of the Etymologicon Magnum, after stringing together a whole series of senseless conjectures, at last stumbles on what looks like the truth. Demeter, it will later be seen, probably came from Crete, and brought her name with her; she is the Earth, but only in this limited sense, as 'Grain-Mother.'

To the modern mind it is surprising to find the processes o agriculture conducted in the main by women, and mirroring themselves in the figures of women-goddesses. But in days when man was mainly concerned with hunting and fighting it was natural enough that agriculture and the ritual attendant on it should fall to the women. Moreover to this social necessity was added, and still is among many savage communities, a deep-seated element of superstition. 'Primitive man,' Mr Payne observes, 'refuses to interfere in agriculture; he thinks it magically dependent for success on woman, and connected with child-bearing.' 'When the women plant maize,' said the Indian to Gumilla, 'the stalk produces two or three ears. Why Because women know how to produce children. They only know how to plant corn to ensure its germinating. Then let them plant it, they know mom than we know.' Such seems to have been the mind of the men of Athens who sent their wives and daughters to keep the Thesmophoria and work their charms and ensure fertility for crops and man.

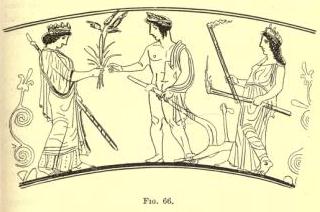

It was mainly in connection with

agriculture, it would seem, that the Earth-goddess developed her

double form as Mother and Maid. The ancient'Lady of the Wild

Things'is both in one or perhaps not consciously either, but at

Eleusis the two figures are clearly outlined; Demeter and Kore

are two persons though one god. They take shape very charmingly

in the design in fig. 66, from an early red-figured skyphos,

found at Eleusis. To the left Demeter stands, holding in her left

hand her sceptre, while with her right she gives the corn-ears to

her nursling, Triptolemos, who holds his 'crooked plough.' Behind

is Kore, the maiden, with her simple chiton for dress, and her

long flowing hair, and the torches she holds as Queen of the

underworld. Mother and Maid in this picture are clearly

distinguished, but not infrequently, when both appear together,

it is impossible to say which is which.

It was mainly in connection with

agriculture, it would seem, that the Earth-goddess developed her

double form as Mother and Maid. The ancient'Lady of the Wild

Things'is both in one or perhaps not consciously either, but at

Eleusis the two figures are clearly outlined; Demeter and Kore

are two persons though one god. They take shape very charmingly

in the design in fig. 66, from an early red-figured skyphos,

found at Eleusis. To the left Demeter stands, holding in her left

hand her sceptre, while with her right she gives the corn-ears to

her nursling, Triptolemos, who holds his 'crooked plough.' Behind

is Kore, the maiden, with her simple chiton for dress, and her

long flowing hair, and the torches she holds as Queen of the

underworld. Mother and Maid in this picture are clearly

distinguished, but not infrequently, when both appear together,

it is impossible to say which is which.

The relation of these early matriarchal, husbandless goddesses, whether Mother or Maid, to the male figures that accompany them is one altogether noble and womanly, though perhaps not what the modern mind holds to be feminine. It seems to halt somewhere half-way between Mother and Lover, with a touch of the patron saint. Aloof from achievement themselves, they choose a local hero for their own to inspire and protect. They ask of him, not that he should love or adore, but that he should do great deeds. Hera has Jason, Athene Perseus, Herakles and Theseus, Demeter and Kore Triptolemos. And as their glory is in the hero's high deeds, so their grace is his guerdon. With the coming of patriarchal conditions this high companionship ends. The women goddesses are sequestered to a servile domesticity, they become abject and amorous.

It is important to note that primarily the two forms of the Earth or Corn-goddess are not Mother and Daughter, but Mother and Maiden, Demeter and Kore. They are, in fact, merely the older and younger form of the same person, hence their easy confusion. The figures of the Mother and Daughter are mythological rather than theological, i.e. they arise from the story-telling instinct:

'Demeter of the beauteous hair, goddess divine, I sing,

She and the slender-ancled maid, her daughter, whom the king

Aidoneus seized, by Zeus'decree. He found her, as she played

Far from her mother's side, who reaps the corn with golden blade.'

The corn is reaped and the earth desolate in winter-time. Aetiology is ready with a human love-story. The maiden, the young fruit of the earth, was caught by a lover, kept for a season, and in the spring-time returns to her mother; the mother is comforted, and the earth blossoms again:

'Thus she spake, and then did Demeter the garlanded yield

And straightway let spring up the fruit of the loamy field.

And all the breadth of the earth, with leaves and blossoming things

Was heavy. Then she went forth to the law-delivering kings

And taught them, Triptolemos first.'

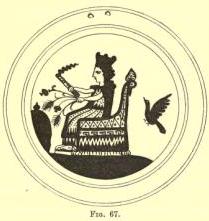

Mythology might work its will, but primitive art never clearly distinguished between the Mother and the Maid, never lost hold of the truth that they were one goddess. On the Boeotian plate in fig. 67 is figured the Corn-goddess, but whether as Mother or Maid it is difficult, I incline to think impossible, to decide. She is a great goddess, enthroned and heavily draped, wearing a high polos on her head. She holds ears of corn, a pomegranate, a torch; before her is an omphalos-like altar, on it what looks like a pomegranate is she Demeter or Persephone ? I incline to think she is both in one; the artist has not differentiated her.

The dead, according to Plutarch's

statement, were called by the Athenians'Demeter's people.'The

ancient 'Lady of the Wild Things' with her guardian lions, keeps

ward over the dead in the tombs of Asia Minor, and every grave

became her sanctuary. But in Greece proper, and especially at

Eleusis, where the Mother and the Maid take mythological,

differentiated form as Demeter and her daughter Persephone, their

individual functions tend more and more to specialize. Demeter

becomes more and more agricultural, more arid more the actual

corn. As Plutarch observes with full consciousness of the

anomalous blend of the human and the physical a poet can say of

the reapers:

The dead, according to Plutarch's

statement, were called by the Athenians'Demeter's people.'The

ancient 'Lady of the Wild Things' with her guardian lions, keeps

ward over the dead in the tombs of Asia Minor, and every grave

became her sanctuary. But in Greece proper, and especially at

Eleusis, where the Mother and the Maid take mythological,

differentiated form as Demeter and her daughter Persephone, their

individual functions tend more and more to specialize. Demeter

becomes more and more agricultural, more arid more the actual

corn. As Plutarch observes with full consciousness of the

anomalous blend of the human and the physical a poet can say of

the reapers:

'What time men shear to earth Demeter's limbs.'

The Mother takes the physical side, the Daughter the spiritual the Mother is more and more of the upper air, the Daughter of the underworld.

Demeter as Thesmophoros has for her sphere more and more the things of this life, laws and civilized marriage; she grows more and more human and kindly, goes more and more over to the humane Olympians, till in the Homeric Hymn she, the Earth-Mother, is an actual denizen of Olympus. The Daughter, at first but the young form of the mother, is in maiden fashion sequestered, even a little farouche; she withdraws herself more and more to the kingdom of the spirit, the things below and beyond:

'She waits for each and other,

She waits for all men born,

Forgets the earth her mother,

The life of fruits and corn.

And spring and seed and swallow

Take wing for her and follow

Where summer song rings hollow

And flowers are put to scorn.'

And in that kingdom aloof her figure waxes as the figure of the Mother wanes:

'daughter of earth, my mother, her crown and blossom of birth,

I am also I also thy brother, I go as I came unto earth.'

She passes to a place unknown of the Olympians, her kingdom is not of this world.

'Thou art more than the Gods, who number the days of our temporal breath,

For these give labour and slumber, but thou, Proserpina, Death.'

All this is matter of late development. At first we have merely the figures of the Two Goddesses, the Two Thesmophoroi, the Two Despoinae. Demeter at Hermione is Chthonia, in Arcadia 1 she is at once Erinys and Lousia. But it is not surprising that, as will later be seen, a religion like Orphism, which concerned itself with the abnegation of this world and the life of the soul hereafter, laid hold rather of the figure of the underworld Kore, and left the prosperous, genial Corn-Mother to make her way alone into Olympus.

The Anodos of the Maiden

In discussing the Boeotian plate (fig. 67), it has been seen that it is not easy always to distinguish in art the figures of the Mother and the Maid. A like difficulty attends the interpretation of the series of curious representations of the earth-goddess now to be considered (figs. 68 72).

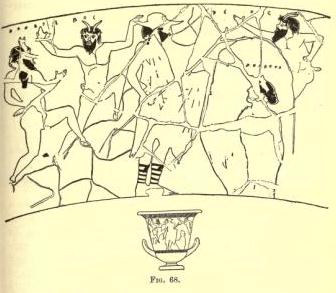

We begin with the vase-painting in

fig. 68, where happily an inscription makes the interpretation

certain. The design is from a red-figured krater, now in the

Albertinum Museum at Dresden. To the right is a conventional

earth-mound . In front of it stands Hermes. He holds not his

kerykeion, but a rude forked rhabdos. It was with the rhabdos, it

will be remembered, that he summoned the souls from the

grave-pithos. Here, too, he is present as Psychagogos; he has

come to summon an earth-spirit, nay more, the Earth-goddess

herself. Out of the artificial mound, which symbolizes the earth

itself, rises the figure of a woman.

We begin with the vase-painting in

fig. 68, where happily an inscription makes the interpretation

certain. The design is from a red-figured krater, now in the

Albertinum Museum at Dresden. To the right is a conventional

earth-mound . In front of it stands Hermes. He holds not his

kerykeion, but a rude forked rhabdos. It was with the rhabdos, it

will be remembered, that he summoned the souls from the

grave-pithos. Here, too, he is present as Psychagogos; he has

come to summon an earth-spirit, nay more, the Earth-goddess

herself. Out of the artificial mound, which symbolizes the earth

itself, rises the figure of a woman.

At first sight we might be inclined to call her Ge, the Earth-Mother, but the figure is slight and maidenly, and over her happily is written (Phe)rophatta. It is the Anodos of Kore the coming of the goddess is greeted by an ecstatic dance of goat-horned Panes.

They are not Satyrs: these, as will later be seen, are horse demons. By the early middle of the 5th century B.C., the date of this red-figured vase, the worship of the Arcadian Pan was well-established at Athens, and the goat-men, the Paries, became the fashionable and fitting attendants of the Earth-Maiden. The inscriptions above their heads can, unfortunately, not be read.

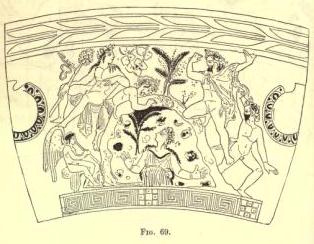

A vase of much later date (fig. 69)

shows us substantially the same scene. The design is from a

red-figured krater in the Berlin Antiquarium. The goddess again

rises from an artificial mound decorated with sprays of foliage.

The attendant figures are different. A goat-legged Pan leans

eagerly over the mound, but Dionysos himself, with his thyrsos,

sits quietly waiting the Anodos, and with him are his real

attendants, the horse-tailed Satyrs. In the left-hand corner a

little winged Love-god plays on the double flutes. The rising

goddess is not inscribed, and she is best left unnamed. She is an

Earth-goddess, but the presence of Dionysos makes us suspect that

there is some reminiscence of Semele. The presence of the

Love-god points, as will be explained later, to the influence of

Orphism.

A vase of much later date (fig. 69)

shows us substantially the same scene. The design is from a

red-figured krater in the Berlin Antiquarium. The goddess again

rises from an artificial mound decorated with sprays of foliage.

The attendant figures are different. A goat-legged Pan leans

eagerly over the mound, but Dionysos himself, with his thyrsos,

sits quietly waiting the Anodos, and with him are his real

attendants, the horse-tailed Satyrs. In the left-hand corner a

little winged Love-god plays on the double flutes. The rising

goddess is not inscribed, and she is best left unnamed. She is an

Earth-goddess, but the presence of Dionysos makes us suspect that

there is some reminiscence of Semele. The presence of the

Love-god points, as will be explained later, to the influence of

Orphism.

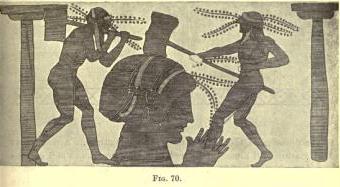

More curious, more instructive, but harder completely to explain, is the design in fig. 70, from a black-figured lekythos in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris.. The colossal head and lifted hands of a woman are rising out of the earth. This time there is no artificial mound, the scene takes place in a temple or sanctuary, indicated by the two bounding columns.

Two men, not Satyrs, are present,

and this time not as idle spectators. Both are armed with great

mallets or hammers, and one of them strikes the head of the

rising woman.

Two men, not Satyrs, are present,

and this time not as idle spectators. Both are armed with great

mallets or hammers, and one of them strikes the head of the

rising woman.

Some possible light is thrown on this difficult vase by the consideration of two others.

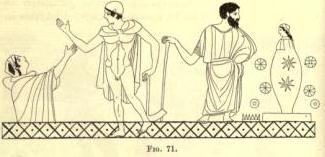

First we have two designs from the obverse and reverse of an amphora, shown together in fig. 71.

On the obverse to the left we have a scene fairly familiar, a goddess rising from the ground, watched by a youth, who holds in his hand some sort of implement, either a pick or a hammer.

The meaning of the reverse design

is conjectural. A man, short of stature and almost deformed in

appearance, looks at a curious and problematic figure, half woman

and half vase, set on a quadrangular basis. Before it, if the

drawing be correct, is a spiked crown; round about, in the field,

a number of rosettes.

The meaning of the reverse design

is conjectural. A man, short of stature and almost deformed in

appearance, looks at a curious and problematic figure, half woman

and half vase, set on a quadrangular basis. Before it, if the

drawing be correct, is a spiked crown; round about, in the field,

a number of rosettes.

A design so problematic is not likely to be a forgery. Before its meaning is conjectured, another vase, whose interpretation is perfectly clear and certain, remains to be considered. Its meaning may serve to elucidate the others.

The design in fig. 72 is from a

red-figured amphora of the finest period, in the Ashmolean Museum

at Oxford. At a first glance, when we see the splendid figure

rising from the ground with outstretched arms, the man with the

hammer and Hermes attendant, we think that we have the familiar

scene of the rising of Kore or Ge.

The design in fig. 72 is from a

red-figured amphora of the finest period, in the Ashmolean Museum

at Oxford. At a first glance, when we see the splendid figure

rising from the ground with outstretched arms, the man with the

hammer and Hermes attendant, we think that we have the familiar

scene of the rising of Kore or Ge.

As such, had no inscriptions existed, the design would certainly have been interpreted. But, as it happens, each figure is carefully inscribed.

To the left Zeus, next to him Hermes, next Epimetheus, and last, not Ge or Kore, but Pandora. Over Pandora, to greet her uprising, hovers a Love-god with a fillet in his outstretched hands.

Pandora rises from the earth; she is the Earth, giver of all gifts. This is made doubly sure by another representation of her birth or rather her making. On the well-known Bale-cylix of the British Museum Pandora, half statue half woman, has just been modelled by Hephaistos, and Athene is in the act of decking her. Pandora she certainly is, but against her is written her other name (A)nesidora, 'she who sends up gifts.' Pandora is a form or title of the Earth-goddess in the Kore form, entirely humanized and vividly personified by mythology.

In the light of this substantial identity of Pandora and the Earth-Kore, it is possible perhaps to offer an explanation of the problematic vase in fig. 71. Have we not on obverse and reverse a juxtaposition of the two scenes, the Rise of Kore, the Making of Pandora? On this showing the short deformed man would be Hephaistos, and Pandora, half woman half vase, may be conceived as issuing from her once famous pithos.

The contaminatio of the myths of the Making of Pandora and the Anodos of Kore may explain also another difficulty. In the making and moulding of Pandora, Hephaistos the craftsman uses his characteristic implement, the hammer. This hammer he also uses to break open the head of Zeus, in representations of the birth of Athene. On vases with the Anodos of Kore the Satyrs or Panes carry and use sometimes an ordinary pick, sometimes a hammer, like the hammer of Hephaistos. The pick is the natural implement for breaking clods of earth, the spade appears to have been unknown before the iron age the hammers have always presented a difficulty. May they not have arisen in connection with the myth of the making of Pandora, and then, by confusion, passed to the Anodos of Kore?

Finally, returning to the difficult design in fig. 70, I would offer another suggestion. The fact that the scene takes place in a sanctuary seems to me to indicate that we have here a representation of some sort of mimetic ritual. The Anodos of Kore was, as has already been seen, dramatized at certain festivals; exactly how we do not know. At the festival of the Charila a puppet dressed as a girl was brought out, beaten, and ultimately hanged in a chasm. Is it not possible that at some festival of the Earth-goddess there was a mimetic enactment of the Anodos, that the earth or some artificially-formed chasm was broken open by picks, and that a puppet or a real woman emerged. It is more likely, I think, that the vase-painter had some such scene in his mind than that the Satyrs with their picks or hammers represent the storm and lightning from heaven beating on the earth to subdue it and compel its fertility. At Megara, near the Prytaneion, Pausanias saw'a rock which was called Anaklethra, "Calling Up," because Demeter, if anyone like to believe it, when she was wandering in search of her daughter, called her up there.'He adds,'the women of Megara to this day perform rites that are analogous to the legend told. 'Unhappily he does not tell us what these rites were. Lucian devotes a half-serious treatise to discussing the scope and merits of pantomimic dancing, Xenophon in his Banquet lets us see that educated guests after dinner preferred the acting of a myth to the tumbling of a dancing girl, but the actual ritual pantomime of the ancients is to us a sealed book. Of one thing we may be sure, that the 'things done' of ritual helped to intensify mythological impersonation as much as, or perhaps more than, the 'things spoken' of the poet.

Pandora

To the primitive matriarchal Greek Pandora was then a real goddess, in form and name, of the Earth, and men did sacrifice to her. By the time of Aristophanes she had become a misty figure, her ritual archaic matter for the oracles of 'Bakis.' The prophet instructing Peisthetairos reads from his script:

'First to Pandora sacrifice a white-fleeced ram.'

The scholiast gives the correct and canonical interpretation 'to Pandora, the earth, because she bestows all things necessary for life.'By his time, and long before, explanation was necessary. Hipponax 5 knew of her; Athenaeus, in his discussion of cabbages, quotes from memory the mysterious lines:

'He grovelled, worshipping the seven-leaved cabbage

To which Pandora sacrificed a cake

At the Thargelia for a pharmakos.'

The passage, though obscure, is of interest because it connects Pandora the Earth-goddess with the Thargelia, the festival of the first-fruits of the Earth. Effaced in popular ritual she emerges in private superstition. Philostratos, in his Life of Apollonius, tells how a certain man, in need of money to dower his daughter, 'sacrificed' to Earth for treasure, and Apollonius, to whom he confided his desire, said, 'Earth and I will help you,' and he prayed to Pandora, sought in a garden, and found the desired treasure.

Pandora is in ritual and matriarchal theology the earth as Kore, but in the patriarchal mythology of Hesiod her great figure is strangely changed and minished. She is no longer Earth-born, but the creature, the handiwork of Olympian Zeus. On a late, red-figured krater in the British Museum, obviously inspired by Hesiod, we have the scene of her birth. She no longer rises halfway from the ground, but stands stiff and erect in the midst of the Olympians. Zeus is there seated with sceptre and thunderbolt, Poseidon is there, Iris and Hermes and Ares and Hera, and Athene about to crown the new-born maiden. Earth is all but forgotten, and yet so haunting is tradition that, in a lower row, beneath the Olympians, a chorus of men, disguised as goat-horned Panes, still dance their welcome. It is a singular reminiscence, and, save as survival, wholly irrelevant.

Hesiod loves the story of the Making of Pandora: he has shaped it to his own bourgeois, pessimistic ends; he tells it twice. Once in the Theogony, and here the new-born maiden has no name, she is just a 'beautiful evil, 'a crafty snare' to mortals. But in the Works and Days he dares to name her and yet with infinite skill to wrest her glory into shame:

'He spake, and they did the will of Zeus, son of Kronos, the Lord,

For straightway the Halting One, the Famous, at his word

Took clay and moulded an image, in form of a maiden fair,

And Athene, the gray-eyed goddess girt her and decked her hair.

And about her the Graces divine and our Lady Persuasion set

Bracelets of gold on her flesh; and about her others yet,

The Hours with their beautiful hair, twined wreaths of blossoms of spring,

While Pallas Athene still ordered her decking in everything.

Then put the Argus-slayer^ the marshal of souls to their place,

Tricks and flattering words in her bosom and thievish ways.

He wrought by the will of Zeus, the Loud-thundering giving her voice,

Spokesman of gods that he is, and for name of her this was his choice,

Because in Olympus the gods joined together then

And all of them gave her, a gift, a sorrow, to covetous men.'

Through all the magic of a poet, caught and enchanted himself by the vision of a lovely woman, there gleams the ugly malice of theological animus. Zeus the Father will have no great Earth-goddess, Mother and Maid in one, in his man-fashioned Olympus, but her figure is from the beginning, so he re-makes it; woman, who was the inspirer, becomes the temptress; she who made all things, gods and mortals alike, is become their plaything, their slave, dowered only with physical beauty, and with a slave's tricks and blandishments. To Zeus, the archpatriarchal bourgeois, the birth of the first woman is but a huge Olympian jest:

'He spake and the Sire of men and of gods immortal laughed.

Such myths are a necessary outcome of the shift from matriarchy to patriarchy, and the shift itself, spite of a seeming retrogression, is a necessary stage in a real advance. Matriarchy gave to women a false because a magical prestige. With patriarchy came inevitably the facing of a real fact, the fact of the greater natural weakness of women. Man the stronger, when he outgrew his belief in the magical potency of woman, proceeded by a pardonable practical logic to despise and enslave her as the weaker. The future held indeed a time when the non-natural, mystical truth came to be apprehended, that the stronger had a need, real and imperative, of the weaker. Physically nature had from the outset compelled a certain recognition of this truth, but that the physical was a sacrament of the spiritual was a hard saying, and its understanding was not granted to the Greek, save here and there where a flicker of the truth gleamed and went through the vision of philosopher or poet.

So the great figure of the Earth-goddess, Pandora, suffered eclipse: she sank to be a beautiful, curious woman; she opened her great grave-pithos, she that was Mother of Life; the Keres fluttered forth, bringing death and disease; only Hope remained. Strangely enough, when the great figure of the Earth-Mother re-emerges, she re-emerges, it will later be seen, as Aphrodite.

The Maiden-Trinities

So far we have seen that a goddess, to the primitive Greek, took twofold form, and this twofold form, shifting and easily interchangeable, is seen to resolve itself very simply into the two stages of a woman's life, as Maiden and Mother. But Greek religion has besides the twofold Mother and Maiden a number of triple forms, Women-Trinities, which at first sight are not so readily explicable. We find not only three Gorgons and three Graiae, but three Semnae, three Moirae, three Charites, three Horae, three Agraulids, and, as a multiple of three, nine Muses.

First it should be noted that the trinity-form is confined to the women goddesses. Greek religion had in Zeus and Apollo the figures of the father and the son, but of a male trinity we find no trace. Zeus and Apollo, incomers from the North, stand alone in this matter of relationship. We do not find the fatherhood of Poseidon emphasized, nor the sonship of Hermes; there is no wide and universal development of the father and the son as there was of the Mother and the Maiden. Dualities and trinities alike seem to be characteristic of the old matriarchal goddesses.

Evidence is not lacking that the trinity-form grew out of the duality. Plutarch notes as one of the puzzling things at Delphi which required looking into, that two Moirae were worshipped there, whereas everywhere else three were canonical. It has already been seen that the number of the Semnae varied between two and three, and that, as three was the ultimate canonical number, we might fairly suppose the number two to have been the earlier. It is the same with the Charites. Pausanias was told in Boeotia that Eteocles not only was 'the first who sacrificed to the Charites,' but, further, he 'instituted three Charites.' The names Eteocles gave to his three Charites the Boeotians did not remember. This is unfortunate, as Orchomenos was the most ancient seat of the worship of the Charites; their images there were natural stones that fell to Eteocles from heaven. Pausanias goes on to note that'among the Lacedaemonians two Charites only were worshipped; their names were Kleta and Phaenna. The Athenians also from ancient days worshipped two Charites, by name Auxo and Hegemone.' Later it appears they fell in with the prevailing fashion, for'in front of the entrance to the Acropolis there were set up the images of three Charites.' The ancient Charites at Orchomenos, at Sparta, at Athens, were two, and it may be conjectured that they took form as the Mother and the Maid.

The three daughters of Cecrops are by the time of Euripides 'maidens threefold'; the three daughters of Erechtheus, who are but their later doubles, are a 'triple yoke of maidens,' and yet in the case of the daughters of Cecrops there is ample evidence that originally they were two, and these two probably a mother and a maid. Aglauros and Pandrosos are definite personalities; they had regular precincts and shrines, known in historical times, Aglauros on the north slope of the Acropolis, where the maidens danced, Pandrosos to the west of the Erechtheion. But of a shrine, precinct, or sanctuary of Herse we have no notice. Ovid probably felt the difficulty; he lodges Herse in a chamber midway between Aglauros and Pandrosos. The women of Athens swore by Aglauros and more rarely by Pandrosos. Aglauros, by whom they swore most frequently, and who gave her name to the Agraulids, was probably the earlier and mother-form. Herse was no good even to swear by; she is the mere senseless etymological eponym of the festival of the Hersephoria, a third sister added to make up the canonical triad. The Hersephoria out of which she is made was not in her honour; it was celebrated to Athene, to Pandrosos, to Ge, to Themis, to Eileithyia.

The women trinities rose out of dualities, but not every duality became a trinity. Plutarch, in discussing the origin of the nine Muses, notes that we have not three Demeters. or three Athenes, or three Artemises. He touches unconsciously on the reason why some dualities resisted the impulse to become trinities. Where personification had become complete, as in the case of Demeter and Kore, or of their doubles, Damia and Auxesia, no third figure could lightly be added. Where the divine pair were still in flux, still called by merely adjectival titles that had not crystallized into proper names, a person more or less mattered little. Thus we have a trinity of Semnae, of Horae, of Moirae, but the Thesmophoroi, who as Thesmophoroi might have easily passed into a trinity, remain always, because of the clear outlines of Demeter and Kore, a duality.

When we ask what was the impulse to the formation of trinities, the answer is necessarily complex. Many strands seem to have gone to their weaving.

First, and perhaps foremost, in the ritual of the lower stratum, of the dead and of chthonic powers, three was, for some reason that escapes us, a sacred number. The dead were thrice invoked; sacrifice was offered to them on the third day; the mourning in some parts of Greece lasted three days; the court of the Areopagus, watched over by deities of the underworld, sat, as has been seen, on three days; at the three ways the threefold Hecate of the underworld was worshipped. It was easy and natural that threefold divinities should arise to keep ward over a ritual so constituted. When the powers of the underworld came to preside over agriculture, the transition from two to three seasons would tend in the same direction. For two seasons a duality was enough the Mother for the fertile summer, the Maid for the sterile winter but, when the seasons became three, a trinity was needed, or at least would be welcomed.

Last, the influence of art must not be forgotten. A central figure of the mother, with her one daughter, composes ill. Archaic art loved heraldic groupings, and for these two daughters were essential. Such compositions as that on the Boeotian amphora in fig. 60 might easily suggest a trinity.

Once the triple form established, it is noticeable that in Greek mythology the three figures are always regarded as maiden goddesses, not as mothers. They may have taken their rise in the Mother and the Maid, but the Mother falls utterly away. The Charites, the Moirae, the Horae, are all essentially maidens. The reverse is the case in Roman religion; trinities of women goddesses of fertility occur frequently in very late Roman art, but they are Matres, Mothers. Three Mothers are rather heavy, and do not dance well.

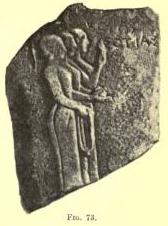

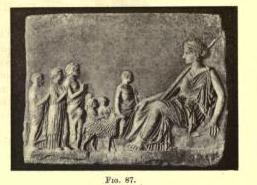

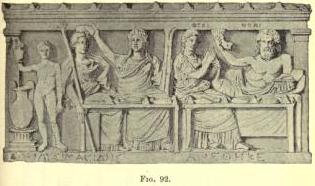

In the archaic votive relief in fig.

73 we have the earliest sculptured representation of the maiden

trinity extant. Had the relief been uninscribed, we should have

been at a loss how to name the three austere figures. Two carry

fruits, and one a wreath. They might be Charites or Eumenides, or

merely nymphs. Most happily the sculptor has left no doubt. He

has written against them Kopas 'Sotias (dedicated) the Korai 'the

Maidens.' Sotias has massed the three stately figures very

closely together; he is reverently conscious that though they are

three persons, yet they are but one goddess. He is half

monotheist.

In the archaic votive relief in fig.

73 we have the earliest sculptured representation of the maiden

trinity extant. Had the relief been uninscribed, we should have

been at a loss how to name the three austere figures. Two carry

fruits, and one a wreath. They might be Charites or Eumenides, or

merely nymphs. Most happily the sculptor has left no doubt. He

has written against them Kopas 'Sotias (dedicated) the Korai 'the

Maidens.' Sotias has massed the three stately figures very

closely together; he is reverently conscious that though they are

three persons, yet they are but one goddess. He is half

monotheist.

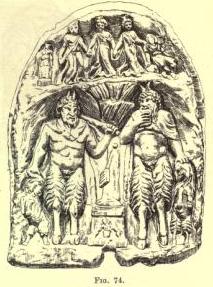

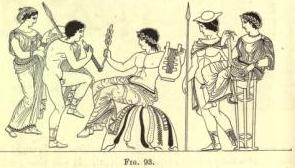

The same origin of the maiden

trinity is clearly indicated in the relief in fig. 74, found

during the 'Enneakrounos' excavations in the precinct of

Dionysos, at Athens.

The same origin of the maiden

trinity is clearly indicated in the relief in fig. 74, found

during the 'Enneakrounos' excavations in the precinct of

Dionysos, at Athens.

The main field of the relief is occupied by two figures of Panes, with attendant goats; between them an altar. The Panes are twofold, not because they are father and son, but because there were two caves of Pan, and the god is thought of as dwelling in each.

After the battle of Marathon the worship of Pan was established in the ancient dancing-ground of the Agraulids; by the time of Euripides, Pan is thought of as host and they as guests:

'0 seats of Pan and rock hard by

To where the hollow Long Rocks lie,

Where before Pallas'temple-bound

Agraulos'daughters three go round

Upon their grassy dancing-ground

To nimble reedy staves,

When thou, Pan, art piping found

Within thy shepherd caves.'

But Pan was a new-comer; the Agraulids were there from the beginning, as early as Cecrops, their snake-tailed father. Busy though he is with Pan, the new-comer, the artist cannot, may not forget the triple maidens. He figures them in the upper frieze, and in quaint fashion he hints that though three they are one. In the left-hand corner he sets the image of a threefold goddess, a Hecate.

But, as time went on, the fact that the three were one is more and more forgotten. They become three single maidens, led by Hermes in the dance; by Hermes Charidotes, whose worship as the young male god of fertility, of flocks and herds, was so closely allied to that of the Charites.

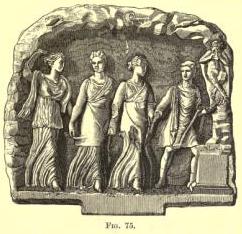

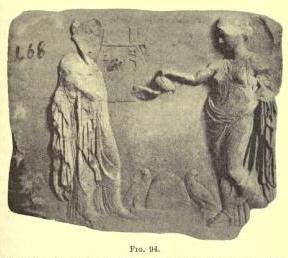

There is no more frequent type of

votive relief than that of which an instance is given in fig. 75.

The cave of Pan is the scene, Pan himself is piping, and the

three maidens, led by Hermes, dance. The cave, the artist knows,

belonged in his days to Pan, but the ancient dwellers there, the

Maidens, still bulk the largest. As a rule the reliefs are not

inscribed, sometimes there is a dedication 'to the Nymphs.' The

personality of the Agraulids has become shadowy, they are merely

Maidens or Brides.

There is no more frequent type of

votive relief than that of which an instance is given in fig. 75.

The cave of Pan is the scene, Pan himself is piping, and the

three maidens, led by Hermes, dance. The cave, the artist knows,

belonged in his days to Pan, but the ancient dwellers there, the

Maidens, still bulk the largest. As a rule the reliefs are not

inscribed, sometimes there is a dedication 'to the Nymphs.' The

personality of the Agraulids has become shadowy, they are merely

Maidens or Brides.

The ancient threefold goddesses, as all-powerful Charites, paled before the Olympians, faded away into mere dancing attendant maidens; but sometimes, in the myths told of these very-Olympians, it is possible to trace the reflection of the older potencies. A very curious instance is to be found in the familiar story of the 'Judgment of Paris', a story whose development and decay are so instructive that it must be examined in some detail.

The Judgment of Paris

The myth in its current form is sufficiently patriarchal to please the taste of Olympian Zeus himself, trivial and even vulgar enough to make material for an ancient Satyr-play or a modern opera-bouffe.

Goddesses three to Ida came

Immortal strife to settle there

Which was the fairest of the three,

And which the prize of beauty should wear.'

The bone of contention is a golden

apple thrown by Eris at the marriage of Peleus and Thetis among

the assembled gods. On it was written,'Let the fair one take it

or, according to some authorities, 'The apple for the fair

one.'

The bone of contention is a golden

apple thrown by Eris at the marriage of Peleus and Thetis among

the assembled gods. On it was written,'Let the fair one take it

or, according to some authorities, 'The apple for the fair

one.'

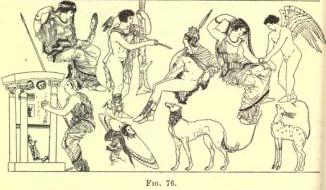

The three high goddesses betake them for judgment to the king's son, the shepherd Paris. The kernel of the myth is, according to this version, a beauty-contest.

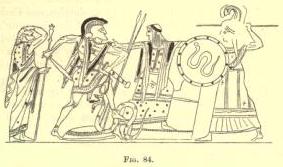

On one ancient vase, and on one only of all the dozens that remain, is the Judgment so figured. The design in fig. 76 is from a late red-figured krater in the Bibliotheque Nationale. Paris, dressed as a Phrygian, is seated in the centre. Hermes is telling of his mission. Grouped around, the three goddesses prepare for the beauty-contest in characteristic fashion. Hera needs no aid, she orders her veil and gazes well satisfied in a mirror; Aphrodite stretches out a lovely arm, and a Love-God fastens 'a bracelet of gold on her flesh'; and Athene, watched only by the great grave dog, goes to a little fountain shrine and, clean-hearted goddess as she is, lays aside her shield, tucks her gown about her, and has - a good wash. Our hearts are with Oenone when she cries:

'"0 Paris,

Give it to Pallas!" but he heard me not,

Or hearing would not hear me, woe is me !'

It is noteworthy that even in this representation, obviously of a beauty-contest, the apple is absent.

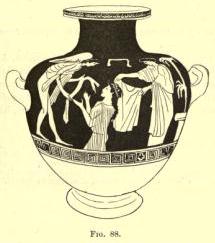

It is quite true that now and again one of the goddesses holds in her hand a fruit. An instance is given in the charming design in fig. 77, from a red-figured stamnos in the British Museum.

Fruit and flowers are held indifferently

by one or all of the goddesses, and the reason will presently

become clear. In the present case Hera holds a fruit, in fig. 81

the two last goddesses hold each a fruit. In fig. 77, against

both Aphrodite and Hera, is inscribed 'Beautiful,' and before the

blinding beauty of the goddesses Paris veils his face. The

inscription enables us to date the vase as belonging to the first

half of the 5th cent. B.C.

Fruit and flowers are held indifferently

by one or all of the goddesses, and the reason will presently

become clear. In the present case Hera holds a fruit, in fig. 81

the two last goddesses hold each a fruit. In fig. 77, against

both Aphrodite and Hera, is inscribed 'Beautiful,' and before the

blinding beauty of the goddesses Paris veils his face. The

inscription enables us to date the vase as belonging to the first

half of the 5th cent. B.C.

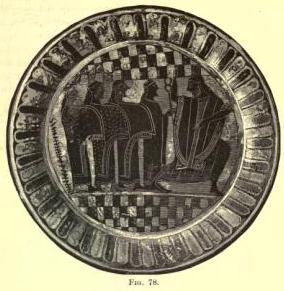

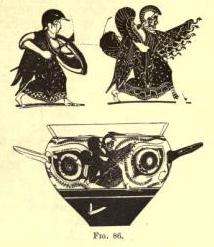

Turning to black-figured vases, a good instance is given in fig. 78 from a patera in the Museo Greco-Etrusco at Florence.

The three goddesses, bearing no

apple and no attributes, the centre one only distinguished by the

spots upon her cloak, follow Hermes into the presence of Paris.

Paris starts away in manifest alarm.

The three goddesses, bearing no

apple and no attributes, the centre one only distinguished by the

spots upon her cloak, follow Hermes into the presence of Paris.

Paris starts away in manifest alarm.

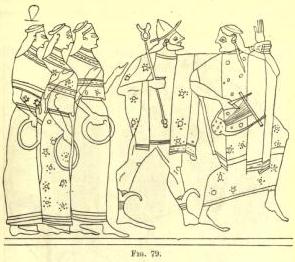

In the curious design in fig. 79, Hermes actually seizes Paris by the wrist to compel his attendance. There is here clearly no question of voluptuous delight at the beauty of the goddesses.

The three maiden figures are scrupulously alike; each carries a wreath. Discrimination would be a hard task. The figures are placed closely together, as in the representation of the Maidens in fig. 73.

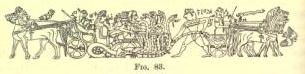

Finally, in fig. 80, a design from

a black-figured amphora, we have the type most frequent of all;

Hermes leads the three goddesses, but in the Judgment of Paris no

figure of Paris is present. Without exaggeration it may be said

that in three out of four representations of the 'Judgment' in

black-figured vase-paintings the protagonist is absent. The scene

takes the form of a simple procession, Hermes leading the three

goddesses.

Finally, in fig. 80, a design from

a black-figured amphora, we have the type most frequent of all;

Hermes leads the three goddesses, but in the Judgment of Paris no

figure of Paris is present. Without exaggeration it may be said

that in three out of four representations of the 'Judgment' in

black-figured vase-paintings the protagonist is absent. The scene

takes the form of a simple procession, Hermes leading the three

goddesses.

This curious fact has escaped the attention of no archaeologist who has examined the art types of the 'Judgment.' It has been variously explained. At a time when vase-paintings were supposed to have had literary sources, it was usual to attempt a literary explanation. Attention was called to the fact that Proklos, in his excerpts of the Kypria, noted that the goddesses, 'by command of Zeus were led to Ida by Hermes'; of this leading it was then supposed that the vase-paintings were 'illustrations.'

Such methods of interpretation are now discredited; no one supposes that the illiterate vase-painter worked with the text of the Kypria before him. Art had its own traditions.

Another explanation, scarcely more

happy, has been attempted. 'Archaic art,'we are told,'loved

processions.'Archaic art, concerned to fill the space of a

circular frieze surrounding a vase, did indeed 'love

processions,'but not with a passion so fond and unreasonable, and

it loved something else better, the lucid telling of a story. In

depicting other myths, archaic art is not driven to express a

story in the terms of an inappropriate procession; it is indeed

largely governed by traditional form, but not to the extent of

tolerating needless obscurity. The'Judgment'is a situation

essentially stationary, with Paris for centre; Hermes is

subordinate.

Another explanation, scarcely more

happy, has been attempted. 'Archaic art,'we are told,'loved

processions.'Archaic art, concerned to fill the space of a

circular frieze surrounding a vase, did indeed 'love

processions,'but not with a passion so fond and unreasonable, and

it loved something else better, the lucid telling of a story. In

depicting other myths, archaic art is not driven to express a

story in the terms of an inappropriate procession; it is indeed

largely governed by traditional form, but not to the extent of

tolerating needless obscurity. The'Judgment'is a situation

essentially stationary, with Paris for centre; Hermes is

subordinate.

We are so used to the procession form that it requires a certain effort of the imagination to conceive of the myth embodied otherwise. But, if we shake ourselves loose of preconceived notions, surely the natural lucid way of depicting the myth would be something after this fashion: Paris in the centre, facing the successful Aphrodite, to whom he speaks or hands the apple or a crown; behind him, to indicate neglect, the two defeated goddesses; Hermes anywhere, to indicate the mandate of the gods. Such a form does indeed appear later, when the vase-painter thought for himself and shook himself free of the dominant tradition. The procession form, as we have it, was not made for the myth, it was merely adapted and taken over, and instantly the suggestion occurs, 'Did not the myth itself in some sense rise out of the already existing art form, an art form in which Paris had no place, in which the golden apple was not?' That form was the ancient type of Hermes leading the three Korai or Charites. In the design in fig. 80, the centre figure Athene is differentiated by her tall helmet and her aegis. Athene is the first of the goddesses to be differentiated and why? She was not victorious, but the vase-painter is an Athenian, and he is concerned for the glory of the Maiden of Athens.

In the design in fig. 81, from a black-figured amphora in the Berlin Museum, the three goddesses are all alike: the first holds a flower, the two last fruits, all fitting emblems of the Charites. Hermes, their leader, carries a huge irrelevant sheep irrelevant for the herald of the gods on his way to Ida, significant for the leader of the Charites, the god of the increase of flocks and herds. Does the picture represent a 'Judgment,' or Hermes and the Charites? Who knows? The doubt is here, as often, more instructive than certainty.

From vases alone it would be sufficiently evident, I think, that the'Judgment of Paris' is really based on Hermes and the Charites, but literary evidence confirms the view. The Kpicris, the Decision, of Paris is always as much a Choice as a Judgment; a Choice somewhat like that invented for Heracles by the philosopher Prodicus, though at once more spontaneous and more subtle than that rather obvious effort at edification. The particular decision is associated in legend with the name of a special hero, of one particular'young man moving to and fro alone, in an empty hut in the firelight.' It is an anguish of hesitancy ending in a choice which precipitates the greatest tragedy of Greek legend. But before Paris was there the Choice was there. The exact elements of the Choice vary in different versions. Athene is sometimes Wisdom and sometimes War. But in general Hera is Royalty or Grandeur; Athene is Prowess; Aphrodite of course is Love. And what exactly has the'young man'to decide? Which of the three is fairest? Or whose gifts he desires the most? It matters not at all, for both are different ways of saying the same thing. Late writers, Alexandrian and Roman, degrade the story into a beauty-contest between three thoroughly personal goddesses, vulgar in itself and complicated by bribery still more vulgar. But early versions scarcely distinguish the goddesses from the gifts they bring. There is no difference between them except the difference of their gifts. They are Charites, Gift-bringers. They are their own gifts. Or, as the Greek put it, their gifts are their tokens. And Hermes had led them long since, in varying forms, before the eyes of each and all of mankind. They might be conceived as undifferentiated, as mere Givers-of-Blessing in general. But it needed only a little reflection to see that Xapis often wars against Xapis, and that if one be chosen, others must be rejected.

As gift-givers the same three goddesses again appear in the myth of the daughters of Pandareos, but this time they are not rivals; and with them comes a fourth, Artemis, whose presence is significant. Homer tells the story by the mouth of Penelope:

'Their father and their mother dear died by the gods'high doom,

The maidens were left ophans alone within their home;

Fair Aphrodite gave them curds and honey of the bee

And lovely wine, and Hera made them very fair to see,

And wise beyond all women-folk. And holy Artemis

Made them to wax in stature, and Athene for their bliss

Taught them all glorious handiworks of woman's artifice.'

The maiden goddesses tend the maidens, but to Homer the Maiden above all others is Artemis, sister of Apollo, daughter of

Zeus. He puts the story into the mouth of Penelope as part of a prayer to Artemis.

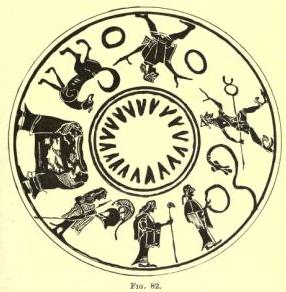

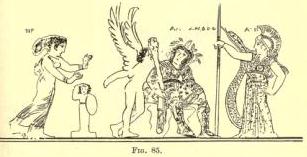

It is curious and significant that

the early vase-painter, in dealing with the story of the

daughters of Pandareos, knows of three goddesses only. The design

in fig. 82 is from the lid of a pyxis, of early black-figured

style, in a private collection at Athens . The vase painter is

concerned mainly with the story of the theft of the great golden

dog of Crete. He makes the dog of supernatural size, with a

splendid high-curled tail. Pandareos has stolen it, and the theft

has been discovered by Hermes, who comes hurriedly up to seize

the prize. Pandareos' is just making off in eager haste. His two

daughters, quaintly enveloped in one cloak to show their close

relationship, stand by. Behind Hermes, with his huge kerykeion,

come in familiar procession the three ancient maidens Aphrodite

with a wreath, her hair arrayed in a quaint twisted pigtail; Hera

with a ram-headed sceptre; Athene with a helmet nearly as big as

herself. The goddesses have come a little proleptically;

Pandareos is still there, the maidens are not yet 'alone within

their home,' but the vase-painter wants to tell all he knows,

and, not being inspired by Homer, he is faithful to the old three

goddesses. Artemis is nowhere.

It is curious and significant that

the early vase-painter, in dealing with the story of the

daughters of Pandareos, knows of three goddesses only. The design

in fig. 82 is from the lid of a pyxis, of early black-figured

style, in a private collection at Athens . The vase painter is

concerned mainly with the story of the theft of the great golden

dog of Crete. He makes the dog of supernatural size, with a

splendid high-curled tail. Pandareos has stolen it, and the theft

has been discovered by Hermes, who comes hurriedly up to seize

the prize. Pandareos' is just making off in eager haste. His two

daughters, quaintly enveloped in one cloak to show their close

relationship, stand by. Behind Hermes, with his huge kerykeion,

come in familiar procession the three ancient maidens Aphrodite

with a wreath, her hair arrayed in a quaint twisted pigtail; Hera

with a ram-headed sceptre; Athene with a helmet nearly as big as

herself. The goddesses have come a little proleptically;

Pandareos is still there, the maidens are not yet 'alone within

their home,' but the vase-painter wants to tell all he knows,

and, not being inspired by Homer, he is faithful to the old three

goddesses. Artemis is nowhere.

But, owing to the influence of Homer and the civilization he represented, the figure of Artemis waxes more and more dominant, and this especially by contrast with the Kore of the lower stratum, Aphrodite. In the Hippolytus of Euripides they are set face to face in their eternal enmity. The conflict is for the poet an issue of two moral ideals, but the human drama is played out against the shadowy background of an ancient racial theomachy, the passion of the South against the cold purity of the North.

Belonging as she does to this later Northern stratum, the figure of Artemis lies properly outside our province, but to one of the ancient maiden trinity, to Athene, she lent much of her cold, clean strength. An epigram to her honour in the Anthology is worth noting, because it shows, clearly and beautifully, how the maidenhood of the worshipper mirrors itself in the worship of a maiden, whether of the South or of the North:

'Maid of the Mere, Timarete here brings,