|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER VII.

THE MAKING OF A GOD.

The Hero as Snake | The Cultus-Titles | Euphemistic Epithets | Heroes and Olympians | Asklepios And The Heroes of Healing | Amynos and Dexion | Herakles | Hero-Feasts | Hippolytos | Zeus Philios | Dionysos on Hero-reliefs

Local Heroine-Worship

FREQUENTLY, in his wanderings through Greece, Pausanias came upon the sanctuaries of local heroines, and these sanctuaries are almost uniformly tombs at which went on the cultus of the dead. At Olympia inside the Altis he noted the Hippodameion or sanctuary of Hippodameia, a large enclosure surrounded by a wall. Into this enclosure once a year women were permitted to enter to sacrifice to Hippodameia and do other rites in her honour. The tomb of Auge was still to be seen at Pergamos, a mound of earth enclosed by a stone basement and on the top the figure of a naked woman. At Leuctra in Laconia there was an actual temple of Cassandra with an image; the people of the place called her Alexandra, 'Helper of Men.' At Sparta Helen had a sanctuary, and in Rhodes she was worshipped as She of the Tree, 'Dendritis' and to her as Dendritis, if we may trust Theocritus, maidens brought offerings. At her wedding they sing:

'fair, gracious maiden, the while we chant our lay,

A wedded wife art thou. But we, at dawning of the day,

Forth to the grassy mead will go, to our old racing place,

And gather wreaths of odorous flowers, and think upon thy face,

Again, again, Helen, on thee, as young lambs in the dew

Think of the milk that fed them and run back to mother ewe.

For thee the first of Maidens shall the lotus creeping low

Be culled to hang in garlands where the shadowy plane doth grow;

To thee where grows the shadowy plane the first oil shall be poured,

Drop by drop from a silver cruse, to hold thy name adored:

And letters on the bark be wrought, for him who goes to see,

A message graven Dorian-wise: " Kneel; I am Helen's tree."'

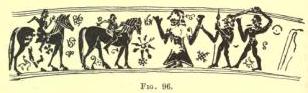

Helen as local heroine had, it would

seem, not only a sanctuary and a sacred tree but a very ancient

image. The design in figs. 95 and 96 is from a lekythos in the

Louvre, of the kind usually known as 'proto-Corinthian.'

Helen as local heroine had, it would

seem, not only a sanctuary and a sacred tree but a very ancient

image. The design in figs. 95 and 96 is from a lekythos in the

Louvre, of the kind usually known as 'proto-Corinthian.'

Its style dates it as not later than the 7th century B.C., and it it our earliest extant monument of 'the rape of Helen.'

The subject seems to have had a certain

popularity in archaic art, as it occurred on the throne of Apollo

at Amyclae. In the centre of the design stands a woman-figure of

more than natural size.

The subject seems to have had a certain

popularity in archaic art, as it occurred on the throne of Apollo

at Amyclae. In the centre of the design stands a woman-figure of

more than natural size.

Two men advance against her from the right; the foremost seizes her by the wrist. In his left hand he holds a sceptre. He is Theseus, and behind him comes Peirithoos, brandishing a great sword. To the left of Helen are her two brothers, the horsemen Kastor and Polydeukes. It is important to note' that Helen is here more image than living woman. Dr Blinkenberg,

who rightly interprets the scene as the rape of Helen, says 'ses mains levees expriment la surprise et I'effroi,' but since the discovery of the early image of the Mycenaean goddess with uplifted hands it will at once be seen that the gesture is hieratic rather than human. This early 7th century document suggests that'the rape of Helen'was originally perhaps the rape of a xoanon from a sanctuary, rather than of a wife from her husband.Be that as it may, the great dominant hieratic figure on the vase is more divine than human.

For Homer, poet of the immigrant Achaeans, Helen of the old order of daughters of the land is a mortal heroine, beautiful and sinful, yet in a sense divine. To the modern poet she is altogether goddess, for she is Beauty herself:

'Light and Shadow of all things that be,

O Beauty, wild with wreckage like the sea,

Say, who shall win thee, thou without a name?

Helen, Helen, who shall die for thee?'

Hebe, another local heroine, has at Phlius a sacred grove and a sanctuary,'most holy from ancient days.' The goddess of the sanctuary was called by the earliest authorities of the place Ganymeda, but later Hebe. Her sanctuary was an asylum, and this was held to be her greatest honour that 'slaves who took refuge there were safe and prisoners released hung their fetters on the trees in her grove.' That a sanctuary should be an asylum is a frequent note of antiquity. When the immigrant conqueror reduces the whole land to subjection, he, probably from superstitious awe, leaves to the conquered their local sanctuary, the one place safe from his tyranny. Hebe-Ganymeda, female correlative of Ganymedes, is promoted to Olympus, but significantly she is admitted only as cupbearer and wife of Herakles. Olympus here as always mirrors human relations. Hera by marriage with Zeus is admitted to full patriarchal citizenship, her shadowy double Hebe is but her Maid of Honour.

As a rule then the local heroine remains merely the object of a local cult. Where she passed upward to the rank of a real divinity, the steps of transition are almost wholly lost. We feel inwardly sure that Hera and Aphrodite were once of mere local import, like Auge or Iphigeneia, but we lack definite evidence. In the case of Athene the local origin, it has been shown, is fairly clear.

The reason why the local heroine failed to emerge to complete godhead is sometimes startlingly clear. Her development was checked midway by the intrusion of a full-blown goddess of the Olympian stock. Near to Cruni in Arcadia Pausanias saw the grave of Callisto. It was a high mound on which grew trees, some of them fruit-bearing, some barren.' On the top of the mound, Pausanias adds, 'is a sanctuary of Artemis with the title Calliste.' Nothing could be clearer. Over the tomb of the old Bear-Maiden, Callisto, daughter of Lycaon, Artemis the Northerner, the Olympian, has superposed her cult, and to facilitate the shift she calls herself Calliste, the Fairest. Possibly here, as at Athens under the title of Brauronia, she kept up the ancient bear-service.

The passage from ghost to goddess is for the most part lost in the mists of time, but of the analogous process from ghost to god the steps are still in historical times clearly traceable. The reason is clear. The intrusion of the patriarchal system, the practice of tracing descent from the father instead of the mother, tended to check, if it was powerless wholly to stop, the worship of eponymous heroines. Conservatism compelled the worship of old established heroines, but no fresh canonizations took place. The ideal woman of Pericles was assuredly not the stuff of which goddesses were made. If we would note the actual process of the manufacture of divinity, it is to heroero-worship we must turn.

The Hero as Snake

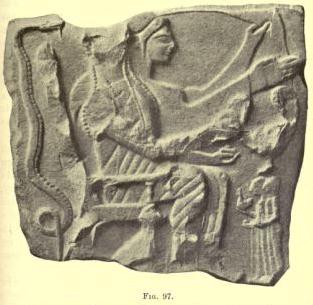

The design in fig. 97 is from an archaic relief of the sixth century B.C., now in the local Museum at Sparta. It forms one of a series of reliefs found near Sparta, all of which are cast approximately in the same type.

A male and a female figure are

seated side by side on a great throne-like chair. The female

figure holds her veil, the male figure a large cantharus or

two-handled cup, as if expecting libation. Worshippers of

diminutive size approach with offerings a cock and some object

that may be a cake, an egg or a fruit. The reliefs are, for the

most part, uninscribed, but on some of rather later date names

are written near the figure, and they are the names of mortals,

e.g. Timocles. It is clear that we have in these monuments

representations of the dead, but the dead conceived of as half

divine, as heroized hence their large size compared with that of

their worshipping descendants. They are Kpein

roves, Better and Stronger Ones.'

A male and a female figure are

seated side by side on a great throne-like chair. The female

figure holds her veil, the male figure a large cantharus or

two-handled cup, as if expecting libation. Worshippers of

diminutive size approach with offerings a cock and some object

that may be a cake, an egg or a fruit. The reliefs are, for the

most part, uninscribed, but on some of rather later date names

are written near the figure, and they are the names of mortals,

e.g. Timocles. It is clear that we have in these monuments

representations of the dead, but the dead conceived of as half

divine, as heroized hence their large size compared with that of

their worshipping descendants. They are Kpein

roves, Better and Stronger Ones.'

The artist of the relief in fig. 97 is determined to make his meaning clear. Behind the chair, equal in height to the seated figures, is a great curled snake, but a snake strangely fashioned. From the edge of his lower lip hangs down a long beard; a decoration denied by nature. The intention is clear; he is a human snake, the vehicle, the incarnation of the dead man's ghost. Snakes lurk about tombs, they are uncanny-looking beasts, and the Greeks are not the only people who have seen in a snake the vehicle of a ghost. M. Henri Jumod, in discussing the beliefs of the Barongas, notes that among this people the snake is regarded as the chikonembo or ghost of a dead man, usually of an ancestor. The snake, so regarded, is feared but not worshipped. A free-thinker among the Barongas, if bored by the too frequent reappearance of the snake ancestor, will kill it, saying 'Come now, we have had enough of you.'

Zeus Meilichios, it has been seen, was worshipped as a snake. If we examine the great snake on his relief in fig. 1 it is seen to be also bearded. The beard in this case is not at the end of the lip, but a good deal further back.

The addition of the beard was no doubt mainly due to frank anthropomorphism; the snake is in a transition stage between animal and human, and human for the artist means divine. He gives the snake a beard to mark his anthropomorphic divinity, just as he gave to the bull river-god on coins a human head with horns. The further question arises, 'Was there anything in nature that might have acted as a possible suggestion of a beard?' An interesting answer to this question has been suggested to me by an eminent authority on snakes, Dr Hans Gadow, and to him I am indebted for the following scientific particulars.

The snake represented in fig. 1 Dr Gadow believes to be the species known as Coelopeltis lacertina. It occurs from Spain to Syria and specimens of 6 ft. long are not uncommon. The creature's head, according to Dr Gadow, is reproduced with admirable fidelity; the name lacertina is due to the lizard-like, instead of snake-like, depressed head. Moreover this species is really poisonous, but only to its proper prey, e.g. mice, rats, lizards, etc., while it is practically harmless to man, on account of the position of the poison fangs, which are far back in the mouth instead of near the front. This is a somewhat exceptional arrange- ment and probably well known to the ancients. In fact the Coelopeltis lacertina is a snake with poison that does not ordinarily strike. On occasion it could bite a man's hand, i.e. if it opened its mouth very wide, as wide as a striking cobra. This position of the dropped jaw, according to Dr Gadow, is very noticeable and must have been observed by the ancients. The angle of the dropped jaw is just that of the beard on the snake in fig. 1 (p. 18). It seems possible and even highly probable that the dropped jaw, seen at a distance, might have suggested a beard, or that an artist representing an actual dropped jaw may have been copied by another who misinterpreted the jaw into a beard. In any case the scheme of the dropped jaw would be ready to hand and would help to soften the anomaly of the bearded snake.

In snake form the hero dwelt in his tomb, and to indicate this fact not uncommonly on vase-paintings we have a snake depicted on the very grave mound itself.

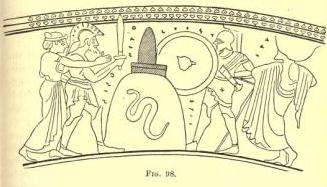

The design in fig. 98, from a

black-figured lekythos in the Museum at Naples, is a good

instance. The funeral mound which occupies the centre of the

design is, on the original vase, white, and on it is painted a

black snake; the mound itself is surmounted by a black stele:

whether the vase-painter regards his snake as painted actually

outside the tomb or as representing the snake-hero actually

resident within, is not easy to determine. The figure of a man on

the left of the tomb with uplifted sword points probably to the

taking of an oath, it may be of vengeance.

The design in fig. 98, from a

black-figured lekythos in the Museum at Naples, is a good

instance. The funeral mound which occupies the centre of the

design is, on the original vase, white, and on it is painted a

black snake; the mound itself is surmounted by a black stele:

whether the vase-painter regards his snake as painted actually

outside the tomb or as representing the snake-hero actually

resident within, is not easy to determine. The figure of a man on

the left of the tomb with uplifted sword points probably to the

taking of an oath, it may be of vengeance.

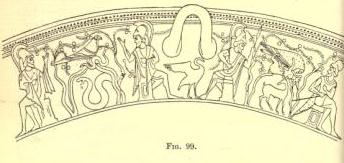

In the curious design in fig. 99, from a kotylos also in the Naples Museum, we have again a funeral mound, again decorated with a huge snake, this time represented with dropped jaw and beard. The tomb seems to have become a sort of mantic shrine.

Two men are seated watching attentively the portent of the eagle and the snake. On the reverse of the vase, to the right, the tomb-mound is decorated with a stag, and the portent is an eagle devouring a hare.

Herodotus notes that among the

Libyan tribe of the Nasamones tombs were used for two purposes,

for the taking of oaths and for dream oracles.' In their oaths

and in the art of divination they observe the following practice:

they take oaths by those among them who are accounted to be most

virtuous and excellent, by touching their tombs, and when they

divine they regularly resort to the monuments of their ancestors,

and having made supplication they go to sleep, and whatever

vision they behold of that they make use.'

Herodotus notes that among the

Libyan tribe of the Nasamones tombs were used for two purposes,

for the taking of oaths and for dream oracles.' In their oaths

and in the art of divination they observe the following practice:

they take oaths by those among them who are accounted to be most

virtuous and excellent, by touching their tombs, and when they

divine they regularly resort to the monuments of their ancestors,

and having made supplication they go to sleep, and whatever

vision they behold of that they make use.'

Herodotus like many travellers was more familiar, it would seem, with the customs of foreigners than with those of his own people. He notes the two customs as though they were alien curiosities, but the practice of swearing on a tomb must have been familiar to the Greeks. The slave in the Choephori says to Electra:

'Reverencing thy father's tomb like to an altar,

Mine inmost thoughts I speak, doing thy best.'

By the hero Sosipolis at Olympia oaths were taken'on the greatest occasions'by Sosipolis who in true hero-fashion was wont to appear in snake-form. That these oaths were taken on his actual tomb we are not told, but the sanctuary of a snake-hero can scarcely in its origin have been other than his tomb. Almost every hero in Greece had his dream oracle. Later as the hero was conceived of as in human rather than animal shape the connection between hero and snake is loosened, and we get the halting, confused theology of Aeneas:

'Doubtful if he should deem the gliding snake

The genius of the place, or if it were

His father's ministrant.'

In fig. 100 we have an altar to a hero found in Lesbos, not the old primitive grave mound which was the true original form, but a late decorative structure such as might have served an Olympian. It is inscribed in letters of Roman date,'The people to Aristandros the hero, son of Cleotimos/ and that the service is to a hero is further emphasized by the snakes sculptured on the top round the hollow cup which served for libations. There are two snakes; it is no longer realized that the hero himself is a snake, but the snake reminiscence clings.

If the question be raised, 'why

did the Greeks image the dead hero as a snake?' no very certain

or satisfactory answer can be offered. Aelian in his treatise on

'The Nature of Animals' says that the backbone of a dead man when

the marrow has decayed turns into a snake. The chance, sudden

apparition of a snake near a dead body may have started the

notion. Plutarch tells how, when the body of Cleomenes was

impaled, the people, seeing a great snake wind itself about his

head, knew that he was 'more than mortal'. Of course, by the time

of Cleomenes, the snake was well established as the vehicle of a

hero, but some such coincidence may very early have given rise to

this association of ideas. Plutarch adds that 'the men of old

time associated the snake most of all beasts with heroes.' They

did this because, he says, philosophers had observed that 'when

part of the moisture of the marrow is evaporated and it becomes

of a thicker consistency it produces serpents.'

If the question be raised, 'why

did the Greeks image the dead hero as a snake?' no very certain

or satisfactory answer can be offered. Aelian in his treatise on

'The Nature of Animals' says that the backbone of a dead man when

the marrow has decayed turns into a snake. The chance, sudden

apparition of a snake near a dead body may have started the

notion. Plutarch tells how, when the body of Cleomenes was

impaled, the people, seeing a great snake wind itself about his

head, knew that he was 'more than mortal'. Of course, by the time

of Cleomenes, the snake was well established as the vehicle of a

hero, but some such coincidence may very early have given rise to

this association of ideas. Plutarch adds that 'the men of old

time associated the snake most of all beasts with heroes.' They

did this because, he says, philosophers had observed that 'when

part of the moisture of the marrow is evaporated and it becomes

of a thicker consistency it produces serpents.'

The snake was not the only vehicle. As has already been noted, the spirit of the dead could take shape as a human-headed bird or even perhaps, if a bird happened to perch on a tomb, as a mere natural hoopoe or swallow. Between the bird-souls and the snake-souls there is this difference. So far as we know, the human-headed bird was purely a creature of mythology, whereas the bearded human snake was the object of a cult. Also the bird-soul, though sometimes male, tends, on the whole, to be a woman; the snake, even when not bearded, is usually the vehicle of a male ghost; as such he is the incarnation rather of the hero than the heroine. So close is the connection that it gave rise to the popular expression'Speckled hero, 'which arose, Photius' explains, because snakes which are speckled are called heroes. Of these snake-heroes and their cultus Homer knows absolutely nothing, but the belief in them is essentially primitive and recrudesces with other popular superstitions.

The Cultus-Titles

The great snake, later worshipped as Zeus Meilichios, was, we have already seen (p. 21), not Zeus himself, but an underworld being addressed by the title Meilichios, gracious, kindly, easy to be in treated. It will now be evident that his snake form marks him as the vehicle or incarnation of a ghost, a local hero. He was only one of a large class of local divinities who were invoked not by proper names but by adjectival epithets, descriptive of their nature, epithets which gradually crystallized into cultus-titles. That these titles were really adjectival is shown sometimes by the actual word, e.g. Meilichios, which retains its adjectival sense, sometimes by the fact that it is taken on as a distinguishing epithet by an Olympian, e.g. Zeus-Amphiaraos. These cultus-titles mark an important stage in the making of a god and must be examined somewhat more in detail.

Herodotus in discussing the origins of Greek theology makes the following significant statement: 'The Pelasgians formerly made all sorts of sacrifice to the gods and invoked them in prayer, as I know from what I heard in Dodona, but they gave to none of them either name or eponym, for such they had not yet heard: they addressed them as gods because they had set all things in order and ruled over all things. Then after a long lapse of time they learnt the names of the other gods which had come from Egypt and much later that of Dionysos. As time went on they inquired of the oracle at Dodona about these names, for the oracle there is held to be the most ancient of all the oracles in Greece and was at that time the only one. When therefore the Pelasgians inquired at Dodona whether they should adopt the names that came to them from the barbarians, the oracle ordained that they should use them. And from that time on they sacrificed to the gods making use of their names.'

If the gods were in these primitive days invoked in prayer, some sort of name, some mode of address they must have had. Is it not at least possible that the advance noted by Herodotus is the shift from mere cultus-title, appropriate to any and every divinity, to actual proper name which defined and crystallized the god addressed? Any and every hero or divinity might rightly be addressed as Meilichios, but a single individual personality is caught and crystallized in the proper name Zeus. When an epithet lost its adjectival meaning, as is the case with Amphiaraos, then and not till then did it denote an individual god. Apollo, Artemis, Zeus himself, may have been adjectival to begin with, mere cultus epithets, but their meaning once lost they have become proper and personal.

It is significant that the shift is said to have taken place owing to an oracle at Dodona. There, accepting Prof. Ridge way's theory, was the first clash of Pelasgian and Achaean, there Zeus and his shadow-wife Dione displaced the ancient Earth-Mother with her dove-priestesses; there surely the Pelasgians with their 'nameless' gods, their heroes and heroines addressed by cultus epithets, met and mingled with the worshippers of Zeus the Father and Apollo the Son and Artemis his sister, and learnt to fix the personalities of their formless shifting divinities, learnt the lesson not from the ancient civilized Egyptians but from the northern 'barbarians.'

The word hero itself is adjectival. A gloss in Hesychius tells us that by hero was meant 'mighty' 'strong' 'noble' 'venerable.' In Homer the hero is the strong man alive, mighty in battle; in cultus the hero is the strong man after death, dowered with a greater, because a ghostly, strength. The dead are, as already noted, Kpeirroves, 'Better and Stronger Ones.' The avoidance of the actual proper name of a dead man is an instructive delicate decency and lives on to-day. The newly dead becomes, at least for a time, 'He' or 'She'; the actual name is felt too intimate. It is a part of the tendency in all primitive and shy souls, a tendency already noted, to remove a little whatever is almost too close, to call your friend 'the kind one,' or 'the old one' or 'the black one' and never name his silent name. Of course the delicate instinct soon crystallizes into definite ritual prescription, and gathers about it the practical cautious utilitarianism of de mortuis nil nisi bene.

It is often said that the Greeks were wont to address their heroized dead and underworld divinities by 'euphemistic' titles, Eumenides for Erinyes, 'Good One,' when they meant 'Bad One.' Such is the ugly misunderstanding view of scholiasts and lexicographers. But a simpler, more human explanation lies to hand. The dead are, it is true, feared, but they are also loved, felt to be friendly, they have been kin on earth, below the earth they will be kind. But in primitive days it is only those who have been kin who will hereafter be kind; the ghosts of your enemies'kin will be unkind; if to them you apply kindly epithets it is by a desperate euphemism, or by a mere mechanical usage.

Of such euphemism Homer has left us a curious example. Zeus would fain remind the assembled gods of the blindness and fatuity of mortal man:

'Then spake the Sire of Gods and Men, and of the Blameless One,

Aigisthos, he bethought him, whom Agamemnon's son,

Far-famed Orestes, slew.'

Aigisthos, traitor, seducer, murderer, craven, is 'the Blameless One.' The outraged morality of the reader is in instant protest. These Olympians, these gods 'who live at ease,' go too far.

The epithets in Homer are often worn very thin, but here, once the point is noted, it is manifest that aiivpwv,'the Blameless One,'is a title perfectly appropriate to Aigisthos as a dead hero. Whatever his life on the upper earth, he has joined the company 'the Stronger and Better Ones.' The epithet in Homer is applied to individual heroes, to a hero's tomb, to magical, half-mythical peoples like the Phaeacians and Aetbiopians who to the popular imagination are half canonized, to the magic island of the god Helios, to the imaginary, half-magical Good Old King. It is used also of the 'convoy' sent by the gods, which of course is magical in character; it is never, I believe, an epithet of the Olympians themselves. There is about the word a touch of what is dead and demonic rather than actually divine.

Homer himself is ignorant of, or at least avoids all mention of, the dark superstitions of a primitive race; he knows nothing at least ostensibly of the worship of the dead, nothing of the cult at his tomb, nothing of his snake-shape; but Homer's epithets came to him already crystallized and came from the underlying stratum of religion which was based on the worship of the dead. And here conies in a curious complication. To Homer, though he calls him mechanically, or if we like'euphemistically/ the'Blameless One/ Aigisthos is really bad, though not perhaps so black as Aeschylus painted him. But was he bad in the eyes of those who first made the epithet? The story of Aigisthos is told by the mouth of the conquerors. Aigisthos is of the old order, of the primitive population, there before the coming of the family of Agamemnon. Thyestes, father of Aigisthos, had been banished from his home; Aigisthos is reared as an alien and returns to claim his own. Clytaemnestra too was of the old order, a princess of the primitive dwellers in the land, regnant in her own right. Agamemnon leaves her, leaves her significantly in the charge of a bard, one of those bards pledged to sing the glory of the conquering Achaeans, and the end is inevitable: she reverts to the prince of the old stock, Aigisthos, to whom we may even imagine she was plighted before her marriage to Agamemnon. Menelaos in like fashion marries a princess of the land and his too are the sorrows of the king-consort. The tomb of Aigisthos was shown to Pausanias. We hear of no cult; possibly under the force of hostile epic tradition it dwindled and died, but in old days we may be sure 'the Blameless One' had his meed of service at Argos, and the epithet itself remains as eternal witness.

Salmoneus to the Achaean mind was scarcely more 'Blameless' than Aigisthos and yet he too bears the epithet. In the Nekuia Odysseus says:

'Then of the throng of women-folk first Tyro I did see,

Child of Salmoneus, Blameless One, a noble sire he.'

Euphemistic Epithets

The case of Salmoneus is highly significant. He too belongs to the old order, as indeed do all the Aeolid figures connected with the group of dead heroines, and more, in his life he was in violent opposition to the new gods. To Hesiod he is 'the Unjust One'. He even dared to counterfeit the thunder and lightning of Zeus, and Zeus enraged slew him with a thunderbolt. The vase-painting already discussed is the very mirror of the picture drawn by Vergil of the insolent king:

'Through the Greek folk, midway in Elis town

In triumph went he; for himself, mad man,

Honours divine he claimed.'

To every worshipper of the new order his crime must have seemed heinous and blasphemous, but among his own people he was glorious before death and probably 'Blameless' after.

The case of Tityos, Son of Earth, presents a close parallel, though Tityos never bore the title of 'Blameless.' To the orthodox worshipper of the Olympians he was the vilest of criminals; as such Homer knew him:

'For he laid hands on Leto, the famous bride of Zeus,

What time she fared to Pytho through the glades of Panopeus.'

And for this his sin he lay in Hades tortured for ever. This is from the Olympian point of view very satisfactory and instructive, but when we turn to local tradition Tityos is envisaged from quite another point of view. Strabo, when he visited Panopeus, learnt that it was the fabled abode of Tityos. He reminds us that it was to the island of Euboea that, according to Homer, the Phaeacians conducted fair-haired Rhadamanthys that he might see Tityos, Son of Earth. We wonder for a moment why the just Rhadamanthys should care to visit the criminal. Homer leaves us in doubt, but Strabo makes the mystery clear. On Euboea, he says, they show a cave called Elarion from Elara who was mother to Tityos, and a hero-shrine of Tityos, and some kind of honours are mentioned which are paid to him.' One 'blameless' hero visits another, that is all. Golden-haired Rhadamanthys found favour with the fair-haired Achaeans; but for Tityos, the son of Earth, there is no place in the Northern Elysium.

We may take it then that the 'euphemistic' epithets were applied at first in all simplicity and faith to heroes and underworld gods by the race that worshipped them. The devotees of the new Achaean religion naturally regarded the heroes and saints of the old as demons. Such was in later days the charitable view taken by the Christian fathers of the Olympian gods in their turn. All the activities that were uncongenial, all the black side of things, were carefully made over by the Olympians to the divinities they had superseded. Only here and there the unconscious use of a crystallized epithet like 'Blameless' lets out the real truth. The ritual prescription that heroes should be worshipped by night, their sacrifice consumed before dawn, no doubt helped the conviction that as they loved the night their deeds were evil. Their ritual too was archaic and not lacking in savage touches. At Daulis Pausanias tells of the shrine of a hero-founder. It was evidently of great antiquity, for the people of the place were not agreed as to who the hero was; some said Phocos, some Xanthippos. Service was done to him every day, and when animal sacrifice was made the Phocians poured the blood of the victim through a hole into the grave; the flesh was consumed on the spot. Such plain-spoken ritual would go far to promote the notion that the hero was bloodthirsty.

Sometimes a ritual prescription marks clearly the antipathy between old and new, between the hero and the Olympian. Pausanias describes in detail the elaborate ceremonial observed in sacrificing to Pelops at Olympia. The hero had a large temenos containing trees and statues and surrounded by a stone wall, and the entrance, as was fitting for a hero, was towards the west. Sacrifice was done into a pit and the victim was a black ram. Pausanias ends his account with the significant words:

'Whoever eats of the flesh of the victim sacrificed to Pelops, whether he be of Elis or a stranger, may not enter the temple of Zeus!

But we are glad to know from Pindar that no spiteful ritual prescription of the Olympian could dim the splendour of the local hero:

'In goodly streams of flowing blood outpoured

Upon his tomb, beside Alpheios' ford,

Now hath he still his share;

Frequent and full the throng that worship there.'

Heroes and Olympians

The scholiast comments on the passage: 'Some say that it was not merely a tomb but a sanctuary of Pelops and that the followers of Herakles sacrificed to him before Zeus.'

At yet another great Pan-Hellenic centre there is the memory, though more faded, of the like superposition of cults. The scholiast on Pindar says that the contest at Nemea was of the nature of funeral games and that it was in honour of Archemoros, but that later, after Herakles had slain the Nemean lion, he'took the games in hand and put many things to rights and ordered them to be sacred to Zeus.'

More commonly there is between the Olympian and the hero all appearance of decent friendliness. A compromise is effected; the main ritual is in honour of the Olympian, but to the hero is offered a preliminary sacrifice. A good instance of this procedure is the worship of Apollo at Amyclae superposed on that of the local hero Hyakinthos. The great bronze statue of Apollo stood on a splendid throne, the decorations of which Pausanias describes in detail. The image itself was rude and ancient, the lower part pillar-shaped, but for all that the god was a new-comer.' The basis of the image was in form like an altar, and they say that Hyakinthos was buried in it, and at the festival of the Hyakinthia before the burnt sacrifice to Apollo, they devote offerings to Hyakinthos into this altar through a bronze door.'

Apollo and Hyakinthos established a modus vivendi. Apollo instituted his regular Olympian sacrifices and left to Hyakinthos his underworld offerings. But not every Olympian was so successful. Ritual is always tenacious. So too at Delphi, Apollo may seat himself on the omphalos, but he is still forced to utter his oracles through the mouth of the priestess of Gaia. Zeus, we have seen, arrogated to himself the title of Meilichios; he had the old snake reliefs dedicated to him, but he was powerless to change the ritual of the hero, and had to content himself, like an underworld god, with holocausts. All that he ceuld do was to emphasize the untruth that he, not the hero, was Meilichios, Easy to be intreated.

All that could be effected by theological animus was done. It has been seen (p. 9) how in the fable of Babrius the hero-ancestor is positively forbidden to give good things, and meekly submits; and, long before Babrius, the blackening process had set in. The bird-chorus in Aristophanes tells of the strange sights it has seen on earth:

'We know of an uncanny spot,

Very dark, where the candles are not;

There to feast with the heroes men go

By day, but at evening, oh no!

For the night time is risky you know.

If the hero Orestes should meet with a mortal by night,

He'd strip him and beat him and leave him an elegant sight.'

Orestes was of course a notable local thief, but the point of the joke is the ill-omened character of a hero. The scholiast says that 'heroes are irascible and truculent to those they meet and possess no power over what is beneficial.' He cites Menander as his authority, but adds on his own account that this explains the fact that'those who go past hero-shrines keep silence.' So easy is it to read a bad meaning into a reverent custom. So possessed are scholiasts and lexicographers by the Olympian prejudice that, even when the word they explain is dead against a bad interpretation, they still maintain it. Hesychius, explaining 'Better or Stronger Ones,' says'they apply the title to heroes, and they seem to be a bad sort of persons; it is on this account that those who pass hero-shrines keep silence lest the heroes should do them some harm.' Among gods, as among mortals, one rule holds good: the king can do no wrong and the conquered no right.

Asklepios And The Heroes of Healing

Heroes, like the ghosts from which they sprang, had of course their black angry side, but, setting aside the prejudice of an Olympianized literature, it is easy to see that in local cultus they would tend rather to beneficence. The ghost you worship and who by your worship is erected into a hero is your kinsman, and the ties of kinship are still strong in the world below. 'In almost all West African districts,' says Miss Mary Kingsley, is a class of spirits called "Well-disposed Ones" and this class is clearly differentiated from "Them," the generic term for non-human spirits. These "Well-disposed Ones" are ancestors and they do what they can to benefit their particular village or family fetish who is not a human spirit or ancestor.' So it was with the Greek; he was careful not to neglect or offend his local hero, but on the whole he relied on his benevolence:

'When a man dies we all begin to say

The sainted one has passed away, he has'fallen asleep,'

Blessed therein that he is vexed no more.

And straight with funeral offerings we do sacrifice

As to a god and pour libations, bidding

Him send good things up here from down below.

The cult of heroes had in it more of human 'tendance' than of demonic aversion.'

The hero had for his sphere of beneficence the whole circle of human activities. Like all primitive divinities he was of necessity a god-of-all-work; a primitive community cannot afford to departmentalize its gods. The local hero had to help his family to fight, to secure fertility for their crops and for themselves, act as oracle when the community was perplexed, be ready for any emergency that might arise, and even on occasion he must mend a broken jug. But most of all he was adored as a Healer. As a Healer he rises very nearly to the rank of an Olympian, but through the gentleness of his office he keeps a certain humanity that prevents complete deification. A typical instance of the Hero-Healer is the god Asklepios.

We conceive of Asklepios as he is figured in many a Greek and Graeco-Roman statue, a reverend bearded god, somewhat of the type of Zeus, but characterized by the staff on which he leans and about which is twined a snake. The snake, our hand-books tell us, is the'symbol of the healing art,'and hence the attribute of Asklepios, god of medicine.

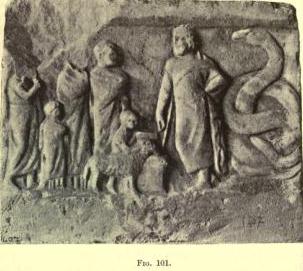

The design in fig. 101, from a

votive relief found in the Asklepieion and now in the National

Museum at Athens, gives cause for reflection.

The design in fig. 101, from a

votive relief found in the Asklepieion and now in the National

Museum at Athens, gives cause for reflection.

The god himself stands in his familiar attitude, waiting the family of worshippers who approach with offerings. A little happy honoured boy is allowed to lead the procession bringing a sheep to the altar. Behind the god is his attribute, a huge coiled snake, his head erect and level with the god he is. Take away the human Asklepios and the scene is yet complete, complete as on the Meilichios relief in fig. 2, the great hero snake and his worshippers.

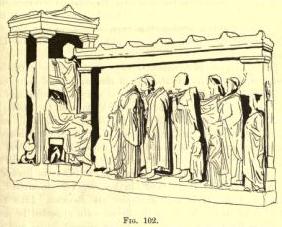

The relief in fig. 101 is under a foot in length, the offering probably of some poor man who clung to his old faith in the healing snake-hero. It forces us in its plain-spoken simplicity to face just the fact that the dedicator of the next relief (fig. 102) is so anxious to conceal. This second relief is the offering of a rich man, the figures are about half life-size; it was found in the same Asklepieion on the south slope of the Acropolis. Asklepios no longer stands citizen-fashion leaning on his staff: he is seated in splendour, and beside him is coiled a very humble attributive snake. Behind are two figures, probably of a son and a daughter, and they all three occupy a separate chapel aloof from their human worshippers.

In token of his humble birth as

the ghost of a mortal the snake always clings to Asklepios, but

it is not the only evidence. An essential part of his healing

ritual was always and everywhere the 'sleeping in' his sanctuary.

The patient who came to be cured must sleep and in a dream the

god either healed him or revealed the means of healing. It was

the dream oracle sent by Earth herself that Apollo the Olympian

came to supersede. All the strange web of human chicanery that

was woven round the dream cure it would here be irrelevant to

examine: only the simple fact need be noted that the prescribed

ritual of sleep was merely a survival of the old dream oracle of

the hero. It was nowise peculiar to Asklepios. When men came to

the beautiful little sanctuary of Amphiaraos at Oropus they

purified themselves, sacrificed a ram, and spreading the skin

under them they went to sleep 'awaiting a revelation in a

dream.'

In token of his humble birth as

the ghost of a mortal the snake always clings to Asklepios, but

it is not the only evidence. An essential part of his healing

ritual was always and everywhere the 'sleeping in' his sanctuary.

The patient who came to be cured must sleep and in a dream the

god either healed him or revealed the means of healing. It was

the dream oracle sent by Earth herself that Apollo the Olympian

came to supersede. All the strange web of human chicanery that

was woven round the dream cure it would here be irrelevant to

examine: only the simple fact need be noted that the prescribed

ritual of sleep was merely a survival of the old dream oracle of

the hero. It was nowise peculiar to Asklepios. When men came to

the beautiful little sanctuary of Amphiaraos at Oropus they

purified themselves, sacrificed a ram, and spreading the skin

under them they went to sleep 'awaiting a revelation in a

dream.'

The dream oracle remained always proper to the earth-born heroes; we hear of no one sleeping in the precinct of Zeus, or of Apollo, and the belief in the magic of sleep long outlasted the service of the Olympians. Today year by year on the festival of the Panagia a throng of sick from the islands round about make their pilgrimage to Tenos, and the sick sleep in the Church and in the precinct and are healed, and in the morning is published the long list of miraculous cures. It is only the truth and the true gods that lived. The Panagia has taken to herself all that was real in ancient faith, in her are still incarnate the Mother and the Maid and Asklepios the Saviour. Like most primitive faiths the belief in the dream cure appealed to something very deep-down and real, however misunderstood and perverted, something in the secret bidding of nature that said, that always will say:

'Sleep Heart, a little free

From thoughts that kill.

Nothing now hard to thee

Or good or ill.

And when the shut eyes see

Sleep's mansions fill,

Night might bring that to be

Day never will.'

The worship of Asklepios, we know from the evidence of an inscription, was introduced at Athens about 421 B.C.: it was still no doubt something of a new excitement when Aristophanes wrote his Plutus. But Athens was not left till 421 B.C. without a Hero-Healer. Asklepios came to Athens as a full-blown god, came first from Thessaly, where he was the rival of Apollo, and finally from his great sanctuary at Epidauros, and, when he came, we have definite evidence that his cult was superimposed on that of a more ancient hero. 'Affiliated' is perhaps the juster word, for when a hero from without took over the cult of an indigenous hero there is no clash of ritual as in the case of an Olympian, no conflict between Amynos and Dexion both heroes alike are content with the simple offering of the pelanos.

Amynos and Dexion

In the course of the 'Enneakrounos' excavations Dr Dorpfeld came upon a small sanctuary consisting of a precinct, an altar, and a well. The precinct wall, the well and the conduit leading to it were clearly, from the style of their masonry, of the date of Peisistratos. Within and around the precinct were votive offerings that pointed to the worship of a god of healing, reliefs representing parts of the human body, breasts and the like, a man holding a huge leg marked with a varicose vein, reliefs of the usual 'Asklepios' type, and above all votive snakes. Had there been no inscriptions the precinct could have been at once claimed as 'sacred to Asklepios,' and we should have been left with the curious problems, 'Why had Asklepios two precincts, one on the south, one on the west of the Akropolis; and, if the god had already a shrine on the west slope in the days of Peisistratos, why did he trouble to make a triumphant entry into Athens on the south slope in 421 B.C.?'

Happily we are left in no such dilemma. On a stele found in the precinct we have the following inscription: 'Mnesiptoleme on behalf of Dikaiophanes dedicated (this) to Asklepios Amynos.' If the inscription stood alone, we should probably decide that Asklepios was worshipped in the precinct under the title of Amynos, the Protector. Whatever the original meaning of the word Asklepios and we may conjecture it was merely a cultus-title it soon became a proper name, and could therefore easily be associated with an adjectival epithet.

A second inscription happily makes it certain that Amynos was not merely an adjective, but an adjectival title of a person distinct from Asklepios. It runs as follows: 'Certain citizens held it just to commemorate concerning the common weal of the members of the thiasos of Arnynos and of Asklepios and of Dexion.' Here we have the names of three personalities manifestly separate and enumerated in significant order. We know Asklepios and most fortunately Dexion. The author of the Etymologicon Magnum, in explaining the word Dexion, says: 'The title was given by the Athenians to Sophocles after his death. They say that when Sophocles was dead the Athenians, wishing to give him added honours, built him a hero-shrine and named him Dexion, the Receiver, from his reception of Asklepios for he received the god in his own house and set up an altar to him.' For the heroization of Sophocles we have earlier evidence than the Etymologicon Magnum. The historian Istros (3rd cent. B.C.) is quoted as saying that the Athenians'on account of the man's virtue passed a vote that yearly sacrifice should be made to him.'

It seems an extraordinary story, but, if we do not press too hard the words of the panegyrist, the explanation is natural enough. Sophocles was not exactly canonised'because of his virtue.' He became a hero, officially, because he had officially received Asklepios, and the 'Receiver' of a god, like the 'Founder' of a town, had a right to ritual recognition. 'Dexion'is the Receiver of the god, and from the fact that the inscription with his name is set up in the little precinct on the west slope of the Acropolis we may be sure his worship went on there. It was in that little precinct, we may conjecture, that he served as priest. This conjecture is made almost certain by the fact that a later inscription (1st cent. B.C.), with a dedication to Amynos and Asklepios, is dated by the priesthood of a 'Sophocles,' probably a descendant of the poet. Sophocles as a hero was not a success, probably he was too alive and human as a poet; he was in his own precinct completely submerged by the god he ( received.'

The theological history of the little precinct is quite clear. The inscription preserves the ritual order of precedence. The sanctuary began, not later than Peisistratos, as an Amyneion, shrine of a local hero worshipped under the title of Amynos, Protector. At some time, probably owing to the recent pestilence which the local hero had failed to avert, it was thought well to affiliate a Healer-god who had attained enormous prestige in the Peloponnesus. The experiment was quietly and carefully tried in the little Amyneion before the foundation of the great Asklepieion on the south slope. It was a very simple matter. A sacred snake would be sent for from Epidauros, to join the local snake of Amynos. Both were snakes, both were healers; the same offerings served for both, the votive limbs, the pelanoi. Sophocles the human Receiver, who had introduced Asklepios in due course, naturally enough dies, and a third healing hero is added to the list. Dexion fades, and Asklepios gradually effaces Amynos and takes his name as a ceremonial title.

Herakles

Because Athens alone is really alive to us, because we know Sophocles as human poet, Asklepios as divine Healer, the case of Amynos, Asklepios, Sophocles seems specially vital and convincing. But we must take it only as one instance of the ladder from earth to heaven that had its lowest rungs planted in every village scattered over Greece a ladder that reached sometimes, but not always or even often, up to high Olympus itself. Whether a local hero became a god depended on a multitude of chances and conditions, the clue to which is lost. If a local hero became famous beyond his own parish the Olympian religion made every effort to meet him half-way. Herakles was of the primitive Pelasgian stock. His name, if the most recent etymology be accepted, means only the young dear Hero the Hero par excellence. No pains were spared to affiliate him. He is allowed the Olympian burnt sacrifice, he is passed through the folds of Hera's robe to make him her child by adoption, he is married in Olympus to Hebe, herself but newly translated, the vase-painter diligently paints his reception into Olympus, he is always elaborately entering, yet he is never really in, he is too much a man to wear at ease the livery of an Olympian, and literature, always over-Olympianized, makes him too often the laughing-stock of the stage.

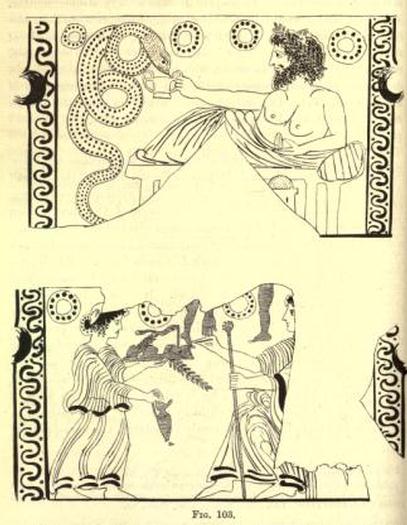

More often it is the fate of a hero to become locally a divinity of healing, but never to emerge as a Pan-Hellenic god. In the design in fig. 103 we have a good instance from a vase found in Boeotia and now in the National Museum at Athens. On the obverse a bearded man, wearing a wreath, reclines at a banquet. A table with cakes stands by his couch. An enormous coiled snake is about to drink from the wine-cup in his hand. On the reverse a woman-goddess holding a sceptre is seated, a girl brings offerings an oinochoe, cakes, a lighted taper. Above are hung votive offerings a hand, two legs, such as hang in the shrines of saints in Brittany and Italy to-day. An interpreter unversed in the complexity of hero-cults would at once name the god with the snake on the obverse Asklepios, the goddess with the votive limbs on the reverse Hygieia; but to these names they have no sort of right. Found as the vase was in Boeotia, the vase-painter more probably intended Amphiaraos, or possibly Trophonios, and Agathe Tyche. All we can say is that they are a couple of healing divinities hero and heroine divinized.

The vase is of late style, and the artist has forgotten that the snake is the hero; he makes him a sort of tame attributive pet, feeding out of the wine-cup. The snake is not bearded, but he has a touch of human unreality in that he is about to drink out of the wine-cup. These humanized snakes are fed with human food; their natural food would be a live bird or a rabbit. Dr Gadow kindly tells me that a snake will lap milk, but if he is to eat his sacrificial food, the pelanos, it must be made exceedingly thin; anything of the nature of a cake or even porridge he could not swallow. And yet the snake on the Acropolis had for his monthly due a 'honey cake,' and at Lebadeia in the shrine of Trophonios, where it was a snake who gave oracles, the inhabitants of the country'cast into his shrine flat cakes steeped in honey.'

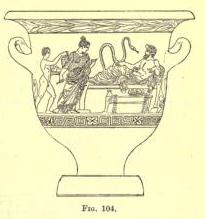

Representations of the hero

reclining at a feast occur very frequently on votive reliefs of a

class shortly to be discussed. They appear very rarely on vases

and only on those of late style. A good instance is the design in

fig. 104 from a late red-figured krater in the Berlin Museum. The

attempt to give a name to the recumbent man is quite fruitless:

the great snake marks him as a dead hero. The woman and boy can

scarcely be said to be worshippers, though the boy brings cakes

and fruit; it is rather the feast that went on in life figured as

continuing after death.

Representations of the hero

reclining at a feast occur very frequently on votive reliefs of a

class shortly to be discussed. They appear very rarely on vases

and only on those of late style. A good instance is the design in

fig. 104 from a late red-figured krater in the Berlin Museum. The

attempt to give a name to the recumbent man is quite fruitless:

the great snake marks him as a dead hero. The woman and boy can

scarcely be said to be worshippers, though the boy brings cakes

and fruit; it is rather the feast that went on in life figured as

continuing after death.

It remains to examine some of the class of votive reliefs closely analogous to the vase-painting in fig. 104, reliefs usually known as 'Hero-Feasts' or 'Funeral Banquets.' They are monuments especially instructive for our purpose, because nowhere else is seen so clearly the transition from hero to god, and also the gradual superposition of the Olympians over local hero-cults.

Hero-Feasts

Plato in the Laws arranges the objects of divine worship in a regular sequence: first the Olympian gods together with those who keep the city: second the underworld gods whose share are things of unlucky omen; third the daemons whose worship is characterized as'orgiastic'; fourth the heroes; fifth ancestral gods. He concludes the list with living parents to whom much honour should be offered. As early as Hesiod theology attempted some differentiation between heroes and daemons; daemons being accounted divine in some higher sense. Of all this minute departmentalism ritual knows nothing. The only recognized distinction is that burnt offerings are the meed of the Olympians, offerings devoted of the chthonic gods. Between the chthonic gods and the whole class of dead men, heroes and daemons, the only distinction observed is, as already noted, that certain chthonic gods from sheer conservatism reject the service of wine, whereas it is apparently acceptable to dead men, to heroes and to daemons not fully divinized.

In like fashion votive reliefs of the type known as Hero-Feasts draw no distinction between hero and daemon, nor indeed do they clearly distinguish between ordinary dead man and hero. As a rule the 'Hero-Feasts' are depicted on reliefs set up in sanctuaries rather than graveyards, but they occur sometimes on actual tombstones set up in actual cemeteries.

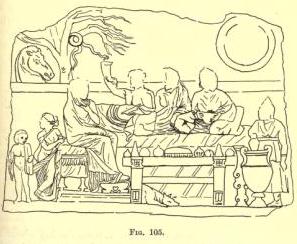

The'Hero-Feast'is found broadcast

over Attica, the Peloponnese and the islands; there is scarcely a

local museum that does not contain specimens. The design in fig.

105 is from a relief in the local museum at Samos. Three heroes

are lying at the banquet; one holds a large rhyton.

The'Hero-Feast'is found broadcast

over Attica, the Peloponnese and the islands; there is scarcely a

local museum that does not contain specimens. The design in fig.

105 is from a relief in the local museum at Samos. Three heroes

are lying at the banquet; one holds a large rhyton.

A snake coiled about a tree is about to drink from it. Snake and tree mark a sanctuary, otherwise the scene is very homelike and non-hieratic.

Of the inscription only two letters remain, and they tell nothing. The round shield and the horse's head and the dog tell us. we have to do with actual heroes, but who they were it is impossible to say.

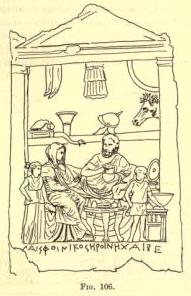

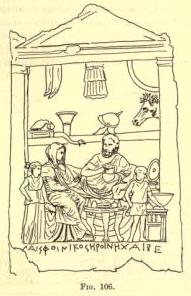

The relief in fig. 106 is also

from Samos. It is of the usual type the recumbent man, the seated

woman, the boy about to draw wine. The field is full of

characteristic tokens; for the man, the horse's head, the

cuirass, helm, shield and greaves; for the woman, the work-basket

of the shape so often occurring on Athenian grave-reliefs, and,

it may be, the tame bird which stands on the casket pecking at a

fruit. The snake is for both, for both are dead. The inscription

at first surprises us; it is as follows: 'Lais daughter of

Phoenix, heroine, hail.' There is no mention of the hero, but on

examination of the stone it is seen that a previous inscription

has been erased. Some one cared more for Lais than for her

husband, hence the palimpsest.

The relief in fig. 106 is also

from Samos. It is of the usual type the recumbent man, the seated

woman, the boy about to draw wine. The field is full of

characteristic tokens; for the man, the horse's head, the

cuirass, helm, shield and greaves; for the woman, the work-basket

of the shape so often occurring on Athenian grave-reliefs, and,

it may be, the tame bird which stands on the casket pecking at a

fruit. The snake is for both, for both are dead. The inscription

at first surprises us; it is as follows: 'Lais daughter of

Phoenix, heroine, hail.' There is no mention of the hero, but on

examination of the stone it is seen that a previous inscription

has been erased. Some one cared more for Lais than for her

husband, hence the palimpsest.

These two specimens from Samos have been selected out of countless others because in them it is quite certain that heroized mortals are represented. The earliest specimens of the 'Hero-Feast 'discovered had no inscriptions, and though horse and snake were present an attempt was made to interpret them as sacred to Asklepios; the snake was'the symbol of healing,'the horse that mysterious creature the 'horse of Hades.' The most ardent devotee of symbolic interpretation can scarcely make mythology out of the greaves and the work-basket.

Reliefs of the 'Hero-Feast' type are all of late date. The earliest one is doubtfully assigned to the end of the 5th century; the great majority are much later. The reason is not far to seek. In the fine period of Greek Art, the period to which we owe most of the grave-reliefs found at Athens, hero-worship is submerged. It is a time of rationalism, and the funeral monuments of that time tend to represent this life rather than the next. I have tried elsewhere to show that early Attic grave-reliefs are cast in the type of the Sparta hero-reliefs, but nowhere in Attic grave-reliefs of the 5th century do we find the dead heroized. But once the age of reason past, hero-worship reemerged, and it would seem in greater force than before.

In the fine period of art hero-reliefs do exist, but not as funeral monuments. One of the earliest and finest we possess is represented in fig. 107. It is not at all of the same type as the 'Hero-Feast,' and is figured here partly for its beauty and interest, partly to mark the contrast. A hero occupies the central place, leading his horse, followed by his hound. That he is a hero we are sure, for in front of him is his low, omphalos-like altar, and to the left a worshipper approaches. Unhappily there is no inscription, but yet we are tempted to give the hero a name.

Horse and horseman are set against

a rocky background. The marble of which the relief is made is

Pen-telic, the style Attic, with many reminiscences of the

Parthenon marbles. It is therefore not too bold to see in the

rocky background a slope of the Acropolis. To the right above the

hero is a seated figure, with only the lower part of the body

draped.

Horse and horseman are set against

a rocky background. The marble of which the relief is made is

Pen-telic, the style Attic, with many reminiscences of the

Parthenon marbles. It is therefore not too bold to see in the

rocky background a slope of the Acropolis. To the right above the

hero is a seated figure, with only the lower part of the body

draped.

Hippolytos

Zeus is so represented and Asklepios. Zeus has no shrine in the slopes of the Acropolis, nor is it probable he would be depicted on a relief of this date seated in casual fashion as a spectator. The figure is almost certainly Asklepios. Given that the figure is Asklepios, the narrative of Pausanias supplies the clue to the remaining figures. 'Approaching the Acropolis by this road, next after the sanctuary of Asklepios is the temple of Themis, and in front of this temple is a mound upreared as a monument to Hippolytos.' Then Pausanias tells the story of Phaedra and Hippolytos; he does not actually mention the sanctuary of Aphrodite, but he says 'the old images were not there in my time, but those I saw were the work of no obscure artists.' Images of course presuppose a sanctuary, and such a sanctuary we now know from inscriptions and votive offerings found on the spot to have existed, and that it was dedicated to Aphrodite Pandemos. The figures on the relief exactly correspond to the account of Pausanias. To the right, i.e. to the East, the figure of Asklepios; next Themis with her temple, clearly indicated by the two'columns between which she stands; immediately in front of her Hippolytos with his sacred altar-mound. Above it Aphrodite, literally 'over Hippolytos'. It is as Euripides knew it:

'And Phaedra then, his father's Queen high born,

Saw him, and as she saw her heart was torn

With great love by the working of my will.

And there, when he was gone, on Pallas' hill

Deep in the rock, that Love no more might roam,

She built a shrine and named it Love-at-Home.

And the rock held it, but its face always

Seeks Trozen o'er the seas.'

It is worth noting that the relief, now in the Torlonia Museum at Rome, was found not far from Aricia, where the hero Virbius, the Latin equivalent of Hippolytos, was worshipped.

It is possible that in the tragedy of the wrath of Aphrodite against the hero who worshipped Artemis, and in the title of the goddess 'over Hippolytos,' later misunderstood as 'because of' for the sake of Hippolytos, we have a reminiscence of a superposition of cults that the actual contest was between a local hero and Aphrodite who had waxed to the glory of an Olympian. Such a view can however scarcely be deduced from the relief in question, which seems to present relations merely topographical and perfectly peaceful.

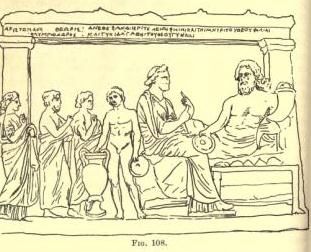

The design in fig. 108, from a

relief in the Jacobsen collection at Ny Carlsberg, Copenhagen,

shows a clearer case of supersession. The design is not earlier

than the 4th century B.C. and of the usual type of 'Hero-Feast';

we have the reclining man, seated wife, attendant cupbearer, and,

to make the scene quite complete, three worshippers of smaller

size. The procession of worshippers is a frequent, though not

uniform, element in the reliefs representing 'Hero-Feasts' When

present they serve to show very clearly that the hero and his

wife are objects of worship. As a rule it is, we have seen,

safest not to name the hero. In the cases so far where he or the

heroine is inscribed, the name has been that of a mortal. In the

present case the inscription has a surprise in store for us.

Assuredly no one, without the inscriptions, would have ventured

to conjecture the inscribed names. The inscription runs as

follows:

The design in fig. 108, from a

relief in the Jacobsen collection at Ny Carlsberg, Copenhagen,

shows a clearer case of supersession. The design is not earlier

than the 4th century B.C. and of the usual type of 'Hero-Feast';

we have the reclining man, seated wife, attendant cupbearer, and,

to make the scene quite complete, three worshippers of smaller

size. The procession of worshippers is a frequent, though not

uniform, element in the reliefs representing 'Hero-Feasts' When

present they serve to show very clearly that the hero and his

wife are objects of worship. As a rule it is, we have seen,

safest not to name the hero. In the cases so far where he or the

heroine is inscribed, the name has been that of a mortal. In the

present case the inscription has a surprise in store for us.

Assuredly no one, without the inscriptions, would have ventured

to conjecture the inscribed names. The inscription runs as

follows:

'Aristomache and Theoris dedicated (it) to Zeus Epiteleios Philios, and to Philia the mother of the god, and to Tyche Agathe the wife of the god.'

Philia, the Friendly One, is mother not wife of Zeus Philios, 'Zeus the Friendly'; it is the old matriarchal relation of Mother and Son. But the dedicators, wedded themselves no doubt after patriarchal fashion, seem to feel a need that Zeus Philios should be married; they give him not his natural shadow-wife Philia she has been used up as mother but Tyche Agathe, 'Good Fortune.' In the procession of worshippers there are two women with a man between them: probably they are his mother and wife and wish to see their relation to him mirrored in their dedication. But they are content with the traditional type of Hero-Feasts, possibly the only type that the conservative workman kept in stock in his workshop.

Zeus Philios

It is worth noting that this interesting relief came from a precinct of Asklepios in Munychia down at the Peiraeus, the same precinct which yielded the snake reliefs (figs. 1 and 2) dedicated to Meilichios. There were also found the relief in fig. 4, several reliefs adorned with snakes only, some reliefs representing Asklepios, and various ritual inscriptions. The precinct seems to have become a sort of melting-pot of gods and heroes. Tyche we know at Lebadeia as the wife of the Agathos Daimon, the Good or Rich Spirit, and it is curious to note that Zeus on the relief holds a cornucopia, symbol of plenty. His other title Epiteleios points the same way. Hesychius tells us that the word etrtrexetaxtts means the same as avvrjois, 'increase,' and Plato gives the name etrtrexetaxtts, 'accomplishments' to family feasts held in thanksgiving for the birth and welfare of children.

It seems obvious that the precinct once belonged to a hero, worshipped under the form of a snake, and as Meilichios, god of the wealth of the underworld a sort of Agathos Daimon or Good Spirit. He must have had two other titles Epiteleios, the Accomplished, and Philios, the Friendly One. At some time or other Asklepios took over the shrine of Meilichios, Philios, Epiteleios, as he took over the shrine of Amynos, but Zeus also put in a claim and the two divided the honours of the place. The old snake-hero was forgotten, overshadowed by the Olympian and the great immigrant healer; but the Olympian does not wholly triumph. He cannot change the local ritual, and he must consent to a certain interchange of attributes.

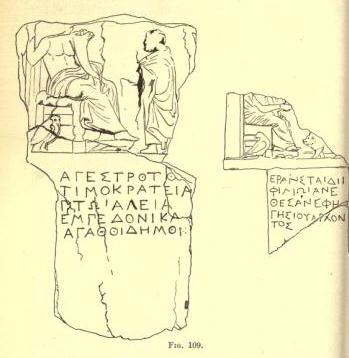

This is quaintly shown in the two

reliefs placed side by side in fig. 109. The larger one to the

left shows a seated god holding a cornucopia; beneath his chair

is an eagle. In deference to this characteristically Olympian

bird we should expect the dedication to be to Zeus.

This is quaintly shown in the two

reliefs placed side by side in fig. 109. The larger one to the

left shows a seated god holding a cornucopia; beneath his chair

is an eagle. In deference to this characteristically Olympian

bird we should expect the dedication to be to Zeus.

We find it is to the 'Good Spirit.' In the smaller relief a similar bird is perched below the chair, and a humble pig is the sacrifice, as it is to Zeus Meilichios; the inscription tells us that'the Club-men dedicated it to Zeus Philios in the archonship of Hegesios.' The relief is dated by this archonship as set up in the year 324/3 B.C. The Friendly Zeus was the god of good fellowship and was of wide popularity. To cheerful, hilarious souls it was comforting to think that there was another Zeus, less remote, more of the cornucopia and less of the thunderbolt, and that he was ready to join a human feast. The diner-out needs and finds a god in his own image, and Zeus Zeus with his title of Philios, accustomed as he was to Homeric banquets, was ready for the post. So the comic parasite reasons:

I wish to explain clearly

What a holy orthodox business this dining-out is

An invention of the gods; the other arts

Were invented by men of talent, not by the gods.

But dining-out was invented by Zeus the Friendly,

By common consent the greatest of all the gods.

Now good old Zeus comes straight into people's houses

In his free and easy way, rich and poor alike.

Wherever he sees a comfortable couch set out

And by its side a table properly laid,

Down he sits to a regular dinner with courses,

Wine and dessert and all, and then off he goes

Straight back home, and he never pays his shot.'

The fooling is obviously based on ritual practice in the 'Hero-Feast' that developed into the Feasts of the Gods, the Theoxenia.

Our argument ends where it began with Zeus Meilichios, an early chthonic stratum of worship, a later Olympian supersession. The two religions, alien in ritual, alien in significance, never more than mechanically fused. We have also seen that the new religion was powerless to alter the old save in name; the Diasia becomes the festival of Zeus, the ritual is a holocaust offered to a snake; Apollo and Artemis take over the Thargelia, but it remains a savage ceremony of magical purification.

It might seem that we had reached the end. In reality, for religion in any deep and mystical sense, we have yet to watch the beginning; we have yet to see the coming of a god, who came from the North and yet was no Achaean, no Olympian, who belonging to the ancient stock revived the ancient ritual, the sacrifice that was in its inner content a sacrifice of purification, but revived it with a significance all his own, the god who took over the ritual of the Anthesteria, Dionysos.

Dionysos on Hero-reliefs

The passing from the old to the

new is very curiously and instructively shown in the two designs

in figs. 110 and 111.

The passing from the old to the

new is very curiously and instructively shown in the two designs

in figs. 110 and 111.

The design in fig. 110 is from a relief found in the harbour of Peiraeus and now in the National Museum at Athens. The material is Pentelic marble; in places the surface has suffered considerably from the corrosion of sea-water. The fine style of the relief dates it as probably belonging to the end of 5th century B.C.

The general type of the relief is of course the same as that of the 'Hero-Feast.' A youth on a couch holds a rhyton, the usual woman is seated at his feet, the usual procession stands to the left. But it is a 'Hero-Feast' with a difference. The group of 'worshippers' are not worshippers; they are talking among themselves, they hold not victims or other offerings, but the implements of the drama a mask, a tambourine. This is clearly seen in the case of the middle figure, a woman. The worshippers are tragic actors. This prepares us for the fact disclosed by the inscriptions beneath the figures of the youth and the attendant woman. Under the youth is written quite clearly Dionysos: under the woman was an inscription of which only two certain letters remain, the two last, la. These inscriptions, it should clearly be noted, are later than the relief itself, probably not earlier than 300 B.C. The name of the woman attendant cannot certainly be made out: the most probable conjecture is (Paid)ia, Play, a natural enough name for a nymph attendant on Dionysos.

The name of the god is certain, and, though the inscription is an afterthought, it certainly voices the intention of the original artist. It is to the honour of Dionysos, not to that of a hero, that the actors with their masks assemble to his honour rather than to his definite worship. But none the less there remains the significant fact that the god has taken over the art-type of the 'Hero-Feast.'

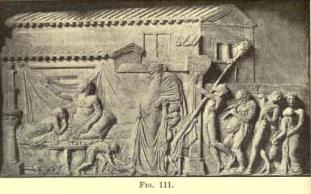

The second relief in fig. 111 tells

in slightly different and more elaborate form the same tale. The

design is from a relief in the Museum at Naples, and is an

instance of a type long known as the'Ikarios reliefs.' Its style

dates it as about the 2nd cent. B.C. It clearly presents a blend

of the 'Hero-Feast' to the left and the triumphal entry of

Dionysos, drunken, elderly, attended by a train of worshippers to

the right. The immigrant god is received by the local hero. What

local hero receives him we cannot say. Legend tells of such

receptions by Ikarios, by Pegasos, by Amphictyon, by Semachos.

The hero must remain unnamed; anyhow he plays to Dionysos the

part played by Sophocles, he is Dexion, Receiver, Host. It is a

Theoxenia, a feasting of the god. The 'Ikarios' reliefs are late,

and, in the euphemistic manner of the time, the representation is

all peace and harmony. The hero, be he who he may, receives in

awe and tells another tale a tale of the forcible wresting of the

honours reverence and gladness the incoming divine guest. But

Herodotus of the hero to the glory of the god. In telling the

early history of Sekyon under the tyrant Cleisthenes he makes

this notable statement:'The inhabitants of Sekyon paid other

honours to Adrastos and they celebrated his misfortunes by tragic

choruses, for at that time they did not honour Diouysos, but

honoured Adrastos. Now Cleisthenes transferred these choruses

(from Adrastos) to Dionysos, but the rest of the sacrifice he

gave to Melanippos.' It is a sudden glimpse into a very human

state of affairs. To put down the cult of Adrastos, the hero of a

family alien to his own, Cleisthenes introduced the worship of a

Theban hero Melanippos. He dared not for some reason give the

tragic choruses to Melanippos; rather than the local enemy should

still have them he hands them over to a popular immigrant god,

Dionysos.

The second relief in fig. 111 tells

in slightly different and more elaborate form the same tale. The

design is from a relief in the Museum at Naples, and is an

instance of a type long known as the'Ikarios reliefs.' Its style

dates it as about the 2nd cent. B.C. It clearly presents a blend

of the 'Hero-Feast' to the left and the triumphal entry of

Dionysos, drunken, elderly, attended by a train of worshippers to

the right. The immigrant god is received by the local hero. What

local hero receives him we cannot say. Legend tells of such

receptions by Ikarios, by Pegasos, by Amphictyon, by Semachos.

The hero must remain unnamed; anyhow he plays to Dionysos the

part played by Sophocles, he is Dexion, Receiver, Host. It is a

Theoxenia, a feasting of the god. The 'Ikarios' reliefs are late,

and, in the euphemistic manner of the time, the representation is

all peace and harmony. The hero, be he who he may, receives in

awe and tells another tale a tale of the forcible wresting of the

honours reverence and gladness the incoming divine guest. But

Herodotus of the hero to the glory of the god. In telling the

early history of Sekyon under the tyrant Cleisthenes he makes

this notable statement:'The inhabitants of Sekyon paid other

honours to Adrastos and they celebrated his misfortunes by tragic

choruses, for at that time they did not honour Diouysos, but

honoured Adrastos. Now Cleisthenes transferred these choruses

(from Adrastos) to Dionysos, but the rest of the sacrifice he

gave to Melanippos.' It is a sudden glimpse into a very human

state of affairs. To put down the cult of Adrastos, the hero of a

family alien to his own, Cleisthenes introduced the worship of a

Theban hero Melanippos. He dared not for some reason give the

tragic choruses to Melanippos; rather than the local enemy should

still have them he hands them over to a popular immigrant god,

Dionysos.

The recumbent hero in the

'Hero-Feasts' is usually represented as reclining at a feast and

as drinking from a large wine-cup, attended by a cupbearer. It

may be conjectured that this type, which does not appear till

late in the 5th century, came in with the worship of Dionysos.

The idea of future bliss as an'eternal drunkenness'came, it will

later be seen, with the religion of Dionysos from the North. By

anticipation we may note a curious fact. On the late Roman coins

of the Bizuae, a Thracian tribe, the type of the Hero-Feast

occurs. An instance is given in fig. 112. A hero is represented

of that we are sure from the cuirass suspended on the tree, from

the horse and from the snake but a hero, I would conjecture,

conceived of as transfigured into the feasting god, Dionysos

himself.

The recumbent hero in the

'Hero-Feasts' is usually represented as reclining at a feast and

as drinking from a large wine-cup, attended by a cupbearer. It

may be conjectured that this type, which does not appear till

late in the 5th century, came in with the worship of Dionysos.

The idea of future bliss as an'eternal drunkenness'came, it will

later be seen, with the religion of Dionysos from the North. By

anticipation we may note a curious fact. On the late Roman coins

of the Bizuae, a Thracian tribe, the type of the Hero-Feast

occurs. An instance is given in fig. 112. A hero is represented

of that we are sure from the cuirass suspended on the tree, from

the horse and from the snake but a hero, I would conjecture,

conceived of as transfigured into the feasting god, Dionysos

himself.

To the examination in detail of the cult of Dionysos we must now turn.