|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER I.

OLYMPIAN AND CHTHONIC RITUAL.

The Diasia | The Dian Fleece | The Attic Calender

IN characterizing the genius of the Greeks Mr Ruskin says:

'there is no dread in their hearts; pensiveness, amazement, often deepest grief and desolation, but terror never. Everlasting calm in the presence of all Fate, and joy such as they might win, not indeed from perfect beauty, but from beauty at perfect rest!

(The Queen of the Air. Part III)

The lovely words are spoken of course mainly with reference to art, but they are meant also to characterize the Greek in his attitude towards the invisible, in his religion meant to show that the Greek, the favoured child of fortune yet ever unspoilt, was exempt from the discipline to which the rest of mankind has been subject, never needed to learn the lesson that in the Fear of the Lord is the beginning of Wisdom.

At first sight it seems as though the statement were broadly true. Greek writers of the fifth century B.C. have a way of speaking of, an attitude towards, religion, as though it were wholly a thing of joyful confidence, a friendly fellowship with the gods, whose service is but a high festival for man. In Homer sacrifice is but, as it were, the signal for a banquet of abundant roast flesh and sweet wine; we hear nothing of fasting, of cleansing, and atonement. This we might perhaps explain as part of the general splendid unreality of the heroic saga, but sober historians of the fifth century B.C. express the same spirit. Thucydides is assuredly by nature no reveller, yet religion is to him in the main 'a rest from toil.' He makes Pericles say:

'Moreover we have provided for our spirit very many opportunities of recreation, by the celebration of games and sacrifices throughout the year.'

(From the Funeral Oration of Pericles in The History of the Peloponnesian War By Thucydides)

Much the same external, quasi-political, and always cheerful attitude towards religion is taken by the 'Old Oligarch.' He is of course thoroughly orthodox and even pious, yet to him the main gist of religion appears to be a decorous social enjoyment. In easy aristocratic fashion he rejoices that religious ceremonials exist to provide for the less well-to-do citizens suitable amusements that they would otherwise lack.

'As to sacrifices and sanctuaries and festivals and precincts, the People, knowing that it is impossible for each poor man individually to sacrifice and feast and have sanctuaries and a beautiful and ample city, has discovered by what means he may enjoy these privileges. The whole state accordingly at the common cost sacrifices many victims, while it is the People who feast on them and divide them among themselves by lot'

and again, as part of the splendour of Athens, he notes that

'she celebrates twice as many religious holidays as any other city.'

The very language used by this typical Athenian gentleman speaks for itself. Burnt-sacrifice, (qnsia) feasting, agonistic games, stately temples are to him the essence of religion; the word sacrifice brings to his mind not renunciation but a social banquet; the temple is not to him so much the awful dwelling-place of a divinity as an integral part of a 'beautiful and ample city.'

Thucydides and Xenophon need and attempt no searching analysis of religion. Socrates of course sought a definition, a definition that left him himself sad and dissatisfied, but that adequately embodied popular sentiment and is of importance for our enquiry. The end of the Euthyphron is the most disappointing thing in Plato; Socrates extracts from Euthyphron what he thinks religion is; what Socrates thought he cannot or will not tell. (Euthyphro.)

Socrates in his enquiry uses not one abstract term for religion - the Greeks have in fact no one word that covers the whole field he uses two, piety (to enwsbe)and holiness (to ocnov).

So far as it is possible to distinguish the two, to eurbes is religion from man's side, his attitude towards the gods, to bnov religion from the gods' side, the claim they make on man. to oriov is the field of what is made over, consecrated to the gods. The further connotations of the word as employed by Orphism will be discussed later. ' Holiness ' is perhaps the nearest equivalent to to oriov in the Euthyphron.

Euthyphron of course begins with cheerful confidence: he and all other respectable men know quite well what piety and holiness are. He willingly admits that holiness is a part of justice, that part of justice that appertains to the gods; it is giving the gods their due. He also allows, not quite seeing to what the argument is tending, that piety and holiness are 'a sort of tendance(depcLTTela) of the gods.' This 'tendance' Socrates presses on, 'must be of the nature of service or ministration' and Euthyphron adds that it is the sort of service that servants show their masters.

Socrates wants to know in what particular work and operation the gods need help and ministration. Euthyphron answers with some impatience that, to put it plainly and cut the matter short, holiness consists in a man understanding how to do what is pleasing to the gods in word and deed, i.e. by prayer and sacrifice. Socrates eagerly seizes his advantage and asks:

'You mean then that holiness is a sort of science of praying and sacrificing? Further he adds, 'sacrifice is giving to the gods, prayer is asking of them, holiness then is a science of asking and giving. If we give to the gods they must want something of us, they must want to 'do business with us. Holiness is then an art in which gods and men do business with each other.

(Euthyphro by Plato)

So Socrates triumphantly concludes, to the manifest discomfort of Euthyphron, who however can urge no tenable objection. He feels as a pious man that the essence of the service or tendance he owes to the gods is of the nature of a freewill tribute of honour, but he cannot deny that the gods demand this as a quid pro quo.

Socrates, obviously unfair though he is, puts his finger on the weak spot of Greek religion as orthodoxly conceived in the fifth century B.C. Its formula is do ut des. It is, as Socrates says, a 'business transaction 'and one in which, because god is greater than man, man gets on the whole the best of it. The argument of the Euthyphron is of importance to us because it clearly defines one, and a prominent, factor in Greek religion, that of service and in this service, this kindly 'tendance', there is no element of fear. If man does his part in the friendly transaction, the gods will do theirs. None of the deeper problems of what we moderns call religion are even touched: there is no question of sin, repentance, sacrificial atonement, purification, no fear of judgment to come, no longing after a future complete beatitude.

Man offers what seems to him in his ignorance a reasonable service to gods conceived of as human and rational. There is no trace of scepticism; the gods certainly exist, otherwise as Sextus Empiricus quaintly argues 'you could not serve them': and they have human natures.

'You do not serve Hippocentauri, because Hippocentauri are non-existent.

(Outlines of Pyrrhonism By Sextus Empiricus)

To the average orthodox Greek the word depaireia, service, tendance, covered a large, perhaps the largest, area of his conception of religion. It was a word expressing, not indeed in the Christian sense a religion whose mainspring was love, but at least a religion based on a rational and quite cheerful mutual confidence. The Greeks have however another word expressive of religion, which embodies a quite other attitude of mind, fear of spirits; fear, not tendance, fear not of gods but of spirit-things, or, to put it abstractly, of the supernatural.

It is certainly characteristic of the Greek mind that the word Seigibaiimovia and its cognates early began to be used in a bad sense, and this to some extent bears out Mr Ruskin's assertion. By the time of Theophrastos o seiaisaifjiv is frankly in our sense 'the superstitious man' and superstition Theophrastos defines as not just and proper reverence but simply 'cowardice in regard to the supernatural. Professor Jebb has pointed out that already in Aristotle Aristotle the word seiaisaifjiv has about it a suspicion of its weaker side. An absolute ruler, Aristotle says, will be the more powerful

'if his subjects believe that he fears the spiritual beings (eav eidlaljlova vofjiioxriv elvai)

but he adds significantly

'he must shew himself such without fatuity' (avev asexrena).

Plutarch has left us an instructive treatise on the fear of the supernatural. He saw in this fear, this superstition, the great element of danger and weakness in the religion that he loved so well. His intellect steeped in Platonism revolted from its unmeaning folly, and his gentle gracious temperament shrank from its cruelty. He sees in superstition not only an error, a wrong judgment of the mind, but that worse thing a 'wrong judgment inflamed by passion'. Atheism is a cold error, a mere dislocation of the mind: superstition is a 'dislocation complicated, inflamed, by a bruise.' 'Atheism is an apathy towards the divine which fails to perceive the good: superstition is an excess of passion which suspects the good to be evil; the superstitious are afraid of the gods yet fly to them for refuge, flatter and yet revile them, invoke them and yet heap blame upon them.'

Superstition grieved Plutarch in two ways. He saw that it terrified men and made them miserable, and he wanted all men to be as cheerful and kindly as himself; it also made men think evil of the gods, fear them as harsh and cruel. He knew that the canonical religion of the poets was an adequate basis for superstitious fear, but he had made for himself a way out of the difficulty, a way he explains in his treatise on 'How the poets ought to be taken.' 'If Ares be evil spoken of we must imagine it to be said of War, if Hephaistos of Fire, if Zeus of Fate, but if anything honourable it is said of the real gods. 'Plutarch was too gentle to say sharply and frankly:

If gods do aught that's shameful, they are no gods.

but he shifted the element of evil, of fear and hate, from his theological ideals to the natural and purely human phenomena from which they had emerged. He wants to treat the gods and regard them as he himself would be treated and regarded, as kindly civilized men.

'What!'he says, 'is he who thinks there are no gods an impious man, while he who describes them as the superstitious man does, does he not hold views much more impious? Well anyhow I for my part would rather people would say of me there never was or is any such a man as Plutarch, than that they should say Plutarch is an unstable, changeable fellow, irritable, vindictive, and touchy about trifles; if you invite friends to dinner and leave out Plutarch, or if you are busy and omit to call on him, or if you do not stop to speak to him, he will fasten on you and bite you, or he will catch your child and beat him, or turn his beast loose into your crops and spoil your harvest.'

But though he is concerned for the reputation of the gods, his chief care and pity are for man. Atheism shuts out a man, he says, from the pleasant things of life. 'These most pleasant things,' he adds in characteristic fashion, 'are festivals and feastings in connection with sacred things, and initiations and orgiastic festivals, and invocations and adorations of the gods. At these most pleasant things the atheist can but laugh his sardonic laugh, but the superstitious man would fain rejoice and cannot, his soul is like the city of Thebes:

" It brims with incense and burnt sacrifice And brims with paeans and with lamentations."

A garland is on his head and pallor on his face, he offers sacrifice and is afraid, he prays and yet his tongue falters, he offers incense and his hand trembles, he turns the saying of Pythagoras into foolishness 'Then we become best when we approach the gods, for those who fear spirits when they approach the shrines and dwellings of the gods make as though they came to the dens of bears and the holes of snakes and the lairs of sea-monsters." In his protest against the religion of fear Plutarch rises to a real eloquence. 'He that dreads the gods dreads all things, earth and sea, air and heaven, darkness and light, a voice, a silence, a dream. Slaves forget their masters in sleep, sleep looses their fetters, salves their gangrened sores, but for the superstitious man his reason is always adreaming but his fear always awake.'

Plutarch is by temperament, and perhaps also by the decadent time in which he lived, unable to see the good side of the religion of fear, unable to realize that in it was implicit a real truth, the consciousness that all is not well with the world, that there is such a thing as evil. Tinged with Orphism as he was, he took it by its gentle side and never realized that it was this religion of fear, of consciousness of evil and sin and the need of purification, of which Orphism took hold and which it transformed to new issues. The cheerful religion of 'tendance' had in it no seeds of spiritual development; by Plutarch's time, though he failed to see this, it had done its work for civilization.

Still less could Plutarch realize that what in his mind was a degradation, superstition in our sense, had been to his predecessors a vital reality, the real gist of their only possible religion. He deprecates the attitude of the superstitious man who enters the presence of his gods as though he were approaching the hole of a snake, and forgets that the hole of a snake had been to his ancestors, and indeed was still to many of his contemporaries, literally and actually the sanctuary of a god. He has explained and mysticized away all the primitive realities of his own beloved religion. It can, I think, be shewn that what Plutarch regards as superstition was in the sixth and even the fifth century before the Christian era the real religion of the main bulk of the people, a religion not of cheerful tendance but of fear and deprecation. The formula of that religion was not do ut des (I give that you may give) but do ut abeas 'I give that you may go, and keep away.' The beings worshipped were not rational, human, law-abiding gods, but vague, irrational, mainly malevolent spirit-things, ghosts and bogeys and the like, not yet formulated and enclosed into god-head. The word tells its own tale, but the thing itself was born long before it was baptized.

Arguments drawn from the use of the word superstition by particular authors are of necessity vague and somewhat unsatisfactory; the use of the word depends much on the attitude of mind of the writer. Xenophon for example uses it in a good sense, as of a bracing confidence rather than a degrading fear.

'The more men are god-fearing, spirit-fearing (setosat zoze), the less do they fear man.'

It would be impossible to deduce from such a statement anything as to the existence of a lower and more 'fearful' stratum of religion.

Fortunately however we have evidence, drawn not from the terminology of religion, but from the certain facts of ritual, evidence which shews beyond the possibility of doubt that the Greeks of the classical period recognised two different classes of rites, one of the nature of 'service' addressed to the Olympians, the other of the nature of 'riddance' or 'aversion' addressed to an order of beings wholly alien. It is this second class of rites which haunts the mind of Plutarch in his protest against the 'fear of spirits'; it is to this second class of rites that the 'Superstitious Man' of Theophrastos was unduly addicted; and this second class of rites, which we are apt to regard as merely decadent, superstitious, and as such unworthy of more than a passing notice and condemnation, is primitive and lies at the very root and base of Greek religion.

First it must clearly be established that the Greeks themselves recognised two diverse elements in the ritual of their state. The evidence of the orator Isocrates on this point is indefeasible. He is extolling the mildness and humanity of the Greeks. In this respect they are, he points out,

'like the better sort of gods. Some of the gods are mild and humane, others harsh and unpleasant.'

He then goes on to make a significant statement:

'Those of the gods who are the source to us of good things have the title of Olympians, those whose department is that of calamities and punishments have harsher titles; to the first class both private persons and states erect altars and temples, the second is not worshipped either with prayers or burnt-sacrifices, but in their case we perform ceremonies of riddance'

Had Isocrates commented merely on the titles of the gods, we might fairly have said that these titles only represent diverse aspects of the same divinities, that Zeus who is Maimaktes, the Raging One, is also Meilichios, Easy-to-be-Intreated, a god of vengeance and a god of love. But happily Isocrates is more explicit; he states that the two classes of gods have not only diverse natures but definitely different rituals, and that these rituals not only vary for the individual but are also different by the definite prescription of the state. The ritual of the gods called Olympian is of burnt-sacrifice and prayer, it is conducted in temples and on altars: the ritual of the other class has neither burnt-sacrifice nor prayer nor, it would seem, temple or altar, but consists in ceremonies apparently familiar to the Greek of under the name of airotroiral, sendings away.''

For airotroiral the English language has no convenient word. Our religion still countenances the fear of the supernatural, but we have outgrown the stage in which we perform definite ceremonies to rid ourselves of the gods. Our nearest equivalent is 'exorcism but as the word has connotations of magic and degraded superstition I prefer to use the somewhat awkward term 'ceremonies of riddance'.

Plato more than once refers to these ceremonies of riddance. In the Laws he bids the citizen, if some prompting intolerably base occur to his mind, as e.g. the desire to commit sacrilege,

'betake yourself to ceremonies of riddance, go as suppliant to the shrines of the gods of aversion, fly from the company of wicked men without turning back.'

The reference to a peculiar set of rites presided over by special gods' is clear. These gods were variously called atrorpotraioi and dtrorrojltraloi, the gods of Aversion and of Sending-away.

Harpocration tells us that Apollodorus devoted the sixth book of his treatise Concerning the gods to the discussion of the deal, the gods of Sending-away. The loss of this treatise is a grave one for the history of ritual, but scattered notices enable us to see in broad outline what the character of these gods of Aversion was. Pausanias at Titane saw an altar, and in front of it a barrow erected to the hero Epopeus, and 'near to the tomb,' he says, 'are the gods of Aversion, beside whom are performed the ceremonies which the Greeks observe for the averting of evils.' Here it is at least probable, though from the vagueness of the statement of Pausanias not certain, that the ceremonies were of an underworld character such as it will be seen were performed at the graves of heroes. The gods of Aversion by the time of Pausanias, and probably long before, were regarded as gods who presided over the aversion of evil; there is little doubt that to begin with these gods were the very evil men sought to avert. The domain of the spirits of the underworld was confined to things evil. Babrius tells us that in the courtyard of a pious man there was a precinct of a hero, and the pious man was wont to sacrifice and pour libations to the hero, and pray to him for a return for his hospitality. But the ghost of the dead hero knew better; only the regular Olympians are the givers of good, his province as a hero was limited to evil only. He appeared in the middle of the night and expounded to the pious man this truly Olympian theology :

'Good Sir, no hero may give aught of good;

For that pray to the gods. We are the givers

Of all things evil that exist for men.'

It will be seen, when we come to the subject of hero-worship, that this is a very one-sided view of the activity of heroes. Still it remains, broadly speaking, true that dead men and the powers of the underworld were the objects of fear rather than love, their cult was of 'aversion 'rather than 'tendance.'

A like distinction is drawn by Hippocrates between the attributes, spheres and ritual of Olympian and chthonic divinities. He says:

'we ought to pray to the gods, for good things to Helios, to Zeus Ouranios, to Zeus Ktesias, to Athene Ktesia, to Hermes, to Apollo; but in the case of things that are the reverse we must pray to Earth and the heroes, that all hostile things may be averted.'

It is clear then that Greek religion contained two diverse, even opposite, factors : on the one hand the element of service (depaireia), on the other the element of aversion. The rites of service were connected by ancient tradition with the Olympians, or as they are sometimes called the Ouranians: the rites of aversion with ghosts, heroes, underworld divinities. The rites of service were of a cheerful and rational character, the rites of aversion gloomy and tending to superstition. The particular characteristics of each set of rites will be discussed more in detail later; for the present it is sufficient to have established the fact that Greek religion for all its superficial serenity had within it and beneath it elements of a darker and deeper significance.

English has no convenient equivalent for aorpopn, which may mean either turning ourselves away from the thing or turning the thing away from us. Aversion, which for lack of a better word I have been obliged to adopt, has too much personal and no ritual connotation. Exorcism is nearer, but too limited and explicit. Dr Oldenberg in apparent unconsciousness of depairda and arrotpotrri uses in conjunction the two words Cultus and Abwehr. To his book, Die Religion des Veda, though he hardly touches on Greek matters, I owe much.

So far we have been content with the general statements of Greek writers as to the nature of their national religion, and the evidence of these writers has been remarkably clear. But, in order to form any really just estimate, it is necessary to examine in detail the actual ritual of some at least of the national festivals. To such an examination the next three chapters will be devoted.

The main result of such an examination, a result which for clearness' sake may be stated at the outset, is surprising. We shall find a series of festivals which are nominally connected with, or as the handbooks say, 'celebrated in honour of various Olympians; the Diasia in honour of Zeus, the Thargelia of Apollo and Artemis, the Anthesteria of Dionysos. The service of these Olympians we should expect to be of the nature of joyous 'tendance.'

To our surprise, when the actual rites are examined, we shall find that they have little or nothing to do with the particular Olympian to whom they are supposed to be addressed; that they are rites not in the main of burnt-sacrifice, of joy and feasting and agonistic contests, but rites of a gloomy underworld character, connected mainly with purification and the worship of ghosts. The conclusion is almost forced upon us that we have here a theological stratification, that the rites of the Olympians have been superimposed on another order of worship. The contrast between the two classes of rites is so marked, so sharp, that the unbroken development from one to the other is felt to be almost impossible.

To make this clear, before we examine a series of festivals in regular calendar order, one typical case will be taken, the Diasia, the supposed festival of Zeus; and to make the argument intelligible, before the Diasia is examined, a word must be said as to the regular ritual of this particular Olympian. The ritual of the several Olympian deities does not vary in essentials; an instance of sacrifice to Zeus is selected because we are about to examine the Diasia, a festival of Zeus, and thereby uniformity is secured.

Agamemnon, beguiled by Zeus in a dream, is about to go forth to battle. Zeus intends to play him false, but all the same he accepts the sacrifice. It is a clear instance of do ut des.

The first act is of prayer and the scattering of barley grains; the victim, a bull, is present but not yet slain:

'They gathered round the bull and straight the barley grain did take,

And 'mid them Agamemnon stood and prayed, and thus he spake:

O Zeus most great, most glorious, Thou who dwellest in the sky

And storm-black cloud, oh grant the dark of evening come not nigh

At sunset ere I blast the house of Priam to black ash,

And burn his doorways with fierce fire, and with my sword-blade gash

His doublet upon Hector's breast, his comrades many a one

Grant that they bite the dust of earth ere yet the day be done.'

Next follows the slaying and elaborate carving of the bull for the banquet of gods and men:

'When they had scattered barley grain and thus their prayer had made,

The bull's head backward drew they, and slew him, and they flayed

His body and cut slices from the thighs, and these in fat

They wrapped and made a double fold, and gobbets raw thereat

They laid and these they burnt straightway with leafless billets dry

And held the spitted vitals Hephaistos'flame anigh

The thighs they burnt; the spitted vitals next they taste, anon

The rest they slice and heedfully they roast till all is done

When they had rested from their task and all the banquet dight,

They feasted, in their hearts no stint of feasting and delight.'

Dr Leaf observes on the passage:

'The significance of the various acts of the sacrifice evidently refers to a supposed invitation to the gods to take part in a banquet. Barley meal is scattered on the victim's head that the gods may share in the fruits of the earth as well as in the meat. Slices from the thigh as the best part are wrapped in fat to make them burn and thus ascend in sweet savour to heaven. The sacrificers after roasting the vitals taste them as a symbolical sign that they are actually eating with gods. When this religious act has" been done, the rest of the victim is consumed as a merely human meal.'

Nothing could be simpler, clearer. There is no mystic communion, no eating of the body of the god incarnate in the victim, no awful taboo upon what has been offered to, made over to, the gods, no holocaust. Homer knows of victims slain to revive by their blood the ghosts of those below, knows of victims on which oaths have been taken and which are utterly consumed arid abolished, but the normal service of the Olympians is a meal shared. The god is Ouranios, so his share is burnt, and the object of the burning is manifestly sublimation not destruction.

With the burnt-sacrifice and the joyous banquet in our minds we turn to the supposed festival of Zeus at Athens and mark the contrast, a contrast it will be seen so great that it compels us to suppose that the ritual of the festival of the Diasia had primarily nothing whatever to do with the worship of Olympian Zeus.

THE DIASIA.

Our investigation begins with a festival which at first sight seems of all others for our purpose most unpromising, the Diasia. Pollux, in his chapter 3 on 'Festivals which take their names from the divinities worshipped' cites the Diasia as an instance 'the Mouseia are from the Muses, the Hermaia from Hermes, the Diasia and Pandia from Zeus, the Panathenaia from Athene.'What could be clearer. It is true that the modern philologist observes what naturally escaped the attention of Pollux, i.e. that the i in Diasia is long, that in a short, but what is the quantity of a vowel as against the accredited worship of an Olympian.

To the question of derivation it will be necessary to return later, the nature of the cult must first be examined. Again at the outset facts seem against us. It must frankly be owned that as early as the middle of the seventh century B.C. in common as well as professional parlance, the Diasia was a festival of Zeus, of Zeus with the title Meilichios.

Our first notice of the Diasia comes to us in a bit of religious history - as amusing as it is instructive, the story of the unworthy trick played by the Delphic oracle on Cylon. Thucydides tells how Cylon took counsel of the oracle how he might seize the Acropolis, and the priestess made answer that he should attempt it 'on the greatest festival of Zeus.' Cylon never doubted that 'the greatest festival of Zeus' was the Olympian festival, and having been (B.C. 640) an Olympian victor himself, he felt that there was about the oracle 'a certain appropriateness.' But in fine oracular fashion the god had laid a trap for the unwary egotist, intending all the while not the Olympian festival but the Attic Diasia, 'for, Thucydides explains,

'the Athenians too have what is called the Diasia, the greatest festival of Zeus, of Zeus Meilichios.'

The passage is of paramount importance because it shows clearly that the obscurity lay in the intentional omission by the priestess of the cultus epithet Meilichios, and in that epithet as will be presently seen lies the whole significance of the cult. Had Zeus Meilichios been named no normal Athenian would have blundered.

Thucydides goes on to note some particulars of the ritual of the Diasia; the ceremonies took place outside the citadel, sacrifices were offered by the whole people collectively, and many of those who sacrificed offered not animal sacrifices but offerings in accordance with local custom. The word iepeta, the regular ritual term for animal sacrifices, is here opposed to local sacrifices. But for the Scholiast the meaning of 'local sacrifices 'would have remained dubious; he explains, and no doubt rightly, that these customary 'local sacrifices' were cakes made in the shape of animals. The principle in sacris simulata pro veris accipi was and is still of wide application, and as there is nothing in it specially characteristic of the Diasia it need not be further exemplified.

Two notices of the Diasia in the Clouds of Aristophanes yield nothing. The fact that Strepsiades bought a little cart at the Diasia for his boy or even cooked a sausage for his relations is of no significance. Wherever any sort of religious ceremony goes on, there among primitive peoples a fair will be set up and outlying relations will come in and must be fed, nor does it concern us to decide whether the cart bought by Strepsiades was a real cart or as the Scholiast suggests a cake-cart. Cakes in every conceivable form belong to the common fund of quod semper quod ubique. Of capital importance however is the notice of the Scholiast on line 408 where the exact date of the Diasia is given. It was celebrated on the 8th day of the last decade of the month Anthesterion i.e. about the 14th of March. The Diasia was a Spring festival and therein as will be shown later lies its true significance.

From Lucian we learn that by his time the Diasia had fallen somewhat into abeyance; in the Icaro-Menippos Zeus complains that his altars are as cold as the syllogisms of Chrysippos. Worn out old god as he was, men thought it sufficient if they sacrificed every six years at Olympia. 'Why is it', he asks ruefully, 'that for so many years the Athenians have left out the Diasia?' It is significant that here again, as in the case of Cylon, the Olympian Zeus has tended to efface from men's mind the ritual of him who bore the title Meilichios. The Scholiast feels that some explanation of an obsolete festival is desirable, and explains:

'the Diasia, a festival at Athens, which they keep with a certain element of chilly gloom, offering sacrifices to Zeus Meilichios.'

This 'chilly gloom' arrests attention at once. What has Zeus of the high heaven, of the upper air, to do with 'chilly gloom' with things abhorrent and abominable? Styx is the chill cold water of death, Hades and the Erinyes are 'chilly ones', the epithet is utterly aloof from Zeus. The Scholiast implies that the chilly gloom comes in from the sacrifice to Zeus Meilichios. Zeus qua Zeus gives no clue, it remains to examine the title Meilichios.

Xenophon in returning from his Asiatic expedition was hindered, we are told, by lack of funds. He piously consulted a religious specialist and was informed that Zeus Meilichios stood in his way and that he must sacrifice to the god as he was wont to do at home. Accordingly on the following day Xenophon

'sacrificed and offered a holocaust of pigs in accordance with ancestral custom and the omens were favourable.'

The regular ancestral ritual to Zeus Meilichios was a holocaust of pigs, and the god himself was regarded as a source of wealth, a sort of Ploutos. Taken by itself this last point could not be pressed, as probably by Xenophon's time men would pray to Zeus pure and simple for any thing and everything; taken in conjunction with the holocaust and the title Meilichios, the fact, it will presently be seen, is significant. There is of course nothing to prove that Xenophon sacrificed at the time of the Diasia, though this is possible; we are concerned now with the cult of Zeus Meilichios in general, not with the particular festival of the Diasia. It may be noted that the Scholiast, on the passage of Thucydides already discussed, says that the 'animal sacrifices 'at the Diasia were yrpofiara, a word usually rendered 'sheep'; but if he is basing his statement on any earlier authority trpoftara may quite well have meant pig or any four-legged household animal; the meaning of the word was only gradually narrowed down to 'sheep.'

It may be said once for all that the exact animal sacrificed is not of the first importance in determining the nature of the god. Pigs came to be associated with Demeter and the underworld divinities, but that is because these divinities belong to a primitive stratum, and the pig then as now was cheap to rear and a standby to the poor. The animal sacrificed is significant of the status of the worshipper rather than of the content of the god. The argument from the pig must not be pressed, though undoubtedly the cheap pig as a sacrifice to Zeus is exceptional.

The manner of the sacrifice, not the material, is the real clue to the significance of the title Meilichios. Zeus as Meilichios demanded a holocaust, a whole burnt-offering. The Zeus of Homer demanded and received the tit-bits of the victim, though even these in token of friendly communion were shared by the worshippers. Such was the custom of the Ouranioi, the Olympians in general. Zeus Meilichios will have all or nothing. His sacrifice is not a happy common feast, it is a dread renunciation to a dreadful power, hence the atmosphere of 'chilly gloom.' It will later be seen that these un-eaten sacrifices are characteristic of angry ghosts demanding placation and of a whole class of underworld divinities in general, divinities who belong to a stratum of thought more primitive than Homer. For the present it is enough to mark that the service of Zeus Meilichios is wholly alien to that of the Zeus of Homer. The next passage makes still clearer the nature of this service.

Most fortunately for us Pausanias, when at Myonia in Locris, visited a sanctuary, not indeed of Zeus Meilichios, but of the Meilichians. He saw there no temple, only a grove and an altar, and he learnt the nature of the ritual. The sacrifices to the Meilichians are at night-time and it is customary to consume the flesh on the spot before the sun is up. Here is no question of Zeus; we have independent divinities worshipped on their own account and with nocturnal ceremonies. The suspicion begins to take shape that Zeus must have taken over the worship of these dread Meilichian divinities with its nocturnal ceremonial. The suspicion is confirmed when we find that Zeus Meilichios is, like the Erinyes, the avenger of, kindred blood. Pausanias saw near the Kephissos an ancient altar of Zeus Meilichios; on it Theseus received purification from the descendants of Phytalos after he had slain among other robbers Sinis who was related to himself through Pittheus.'

Again Pausanias tells us that, after an internecine fray, the Argives took measures to purify themselves from the guilt of kindred blood, and one measure was that they set up an image of Zeus Meilichios. Meilichios, Easy-to-be-entreated, the Gentle, the Gracious One, is naturally the divinity of purification, but he is also naturally the other euphemistic face of Maimaktes, he who rages eager, panting and thirsting for blood. This Hesychius tells us in an instructive gloss. Maimaktes-Meilichios is double-faced like the Erinyes-Eumenides. Such undoubtedly would have been the explanation of the worship of Zeus Meilichios by any educated Greek of the fifth century B.C. with his monotheistic tendencies. Zeus he would have said is all in all, Zeus Meilichios is Zeus in his underworld aspect Zeus-Hades.

Pausanias saw at Corinth three images of Zeus, all under the open sky. One he says had no title, another was called He of the underworld, (0owos), the third The Highest. What earlier cults this triple Zeus had absorbed into himself it is impossible to say.

Such a determined monotheism is obviously no primitive conception, and it is interesting to ask on what facts and fusion of facts it was primarily based. Happily where literature and even ritual leave us with suspicions only, art compels a clearer definition.

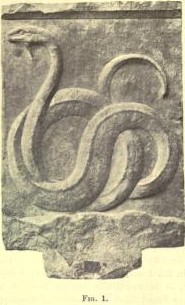

FIG. 1.

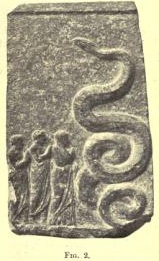

FIG. 2.

The two reliefs in figs. 1 and 2 were found at the Peiraeus and are now in the Berlin Museum. From the inscription on the relief in fig. 1 and from numerous other inscribed reliefs found with it, it is practically certain that at the place in which they were found Zeus Meilichios was worshipped. In any case the relief in fig. 1 is clearly dedicated to him. Above the splendid coiled beast is plainly inscribed to Zeus Meilichios.

So astonishing is the inscription that it drove a man of M. Foucart's learning and ability into strange straits. He was the first to attempt the interpretation of these remarkable reliefs, and so determined is he that the Hellenic Zeus is not, cannot be, a mere snake that he resorts to the perfectly gratuitous assumption that Meilichios is Moloch (Melek) and that the reliefs are dedicated by foreigners to their foreign god. We have no evidence that Moloch was figured as a snake, but anything is good enough for a foreigner. This explanation, though supported by a great name, was too preposterous long to command attention and another way was sought out of the difficulty. The snake, it was suggested, was not the god himself, it was his attribute. Again the assumption is baseless. Zeus is one of the few Greek gods who never appear attended by a snake. Asklepios, Hermes, Apollo, even Demeter and Athene have their snakes, Zeus never. Moreover when the god developed from snake form to human form, as, it will later be shown, was the case with Asklepios, the snake he once was remains coiled about his staff or attendant at his throne. In the case of Zeus Meilichios in human form the snake he once was not disappears clean and clear.

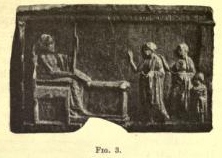

The explanation of the snake as merely an attribute is indeed impossible to any unbiassed critic who looks at the relief in fig. 2. Here clearly the snake is the object worshipped by the woman and two men who approach with gestures of adoration. The colossal size of the beast as ifc towers above its human adorers is the Magnificat of the artist echoed by the worshippers. When we confront the relief in fig. 3, also found at the Peiraeus, with those in figs. 1 and 2, the secret is out at last.

In fig. 3 a man followed by a woman and

child approaches an altar, behind which is seated a bearded god

holding a sceptre and patera for libation. Above is clearly

inscribed 'Aristarche to Zeus Meilichios' ( Apiardpxn Au Meixitp).

In fig. 3 a man followed by a woman and

child approaches an altar, behind which is seated a bearded god

holding a sceptre and patera for libation. Above is clearly

inscribed 'Aristarche to Zeus Meilichios' ( Apiardpxn Au Meixitp).

And the truth is nothing more or less than this. The human-shaped Zeus has slipped himself quietly into the place of the old snake-god. Art sets plainly forth what has been dimly shadowed in ritual and mythology. It is not that Zeus the Olympian has demon of the lower world, Meilichios. Meilichios is no foreign Moloch, he is home-grown, autochthonous before the formulation of Zeus.

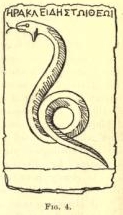

How the shift may have been effected art

again helps us to conjecture. In the same sanctuary at the

Peiraeus that yielded the reliefs in figs. 1 and 2 was found the

inscribed relief in fig. 4. We have a similar bearded snake and

above is inscribed 'Heracleides to the god.'The worshipper is not

fencing, uncertain whether he means Meilichios or Zeus; he brings

his offering to the local precinct where the god is a snake and

dedicates it to the god, the god of that precinct. It is not

monotheism, rather it is parochialism, but it is a conception

tending towards a later monotheism. When and where the snake is

FIG. 4. simply 'the god' the fusion with Zeus is made easy.

How the shift may have been effected art

again helps us to conjecture. In the same sanctuary at the

Peiraeus that yielded the reliefs in figs. 1 and 2 was found the

inscribed relief in fig. 4. We have a similar bearded snake and

above is inscribed 'Heracleides to the god.'The worshipper is not

fencing, uncertain whether he means Meilichios or Zeus; he brings

his offering to the local precinct where the god is a snake and

dedicates it to the god, the god of that precinct. It is not

monotheism, rather it is parochialism, but it is a conception

tending towards a later monotheism. When and where the snake is

FIG. 4. simply 'the god' the fusion with Zeus is made easy.

In fig. 5 is figured advisedly a monument

of snake worship, which it must be distinctly noted comes, not

from the precinct of Zeus Meilichios at the Peiraeus, but from

Eteonos in Boeotia.

In fig. 5 is figured advisedly a monument

of snake worship, which it must be distinctly noted comes, not

from the precinct of Zeus Meilichios at the Peiraeus, but from

Eteonos in Boeotia.

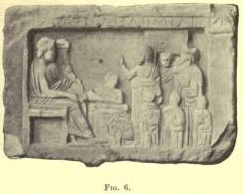

When we come to the discussion of hero-worship, it will be seen that all over Greece the dead hero was worshipped in snake form and addressed by euphemistic titles akin to that of Meilichios. The relief from Boeotia is a good instance of such worship and is chosen because of the striking parallelism of its art type with that of the Peiraeus relief in fig. 3. The maker of this class of votive reliefs seems to have kept in stock designs of groups of pious worshippers which he could modify as required and to which the necessary god or snake and the appropriate victim could easily be appended. Midway in conception between the Olympian Zeus with his sceptre and the snake demon stands another relief (fig. 6), also from the Peiraeus sanctuary. Meilichios is human, a snake no longer, but he is an earth god, he bears the cornucopia, his victim is the pig. He is that Meilichios to whom Xenophon offered the holocaust of pigs, praying for wealth; he is also the Zeus-Hades of Euripides. We might have been tempted to call him simply Hades or Ploutos but for the inscription, 'Kritoboule to Zeus Meilichios,'which makes the dedication certain.

By the light then of these reliefs the duality, the inner discrepancy of Zeus Meilichios admits of a simple and straightforward solution. It is the monument of a superposition of cults.

FIG. 6.

But the difficulty of the name of the festival, Diasia, remains. There is no reason to suppose that the name was given late; and, if primitive, how can we sever it from Atos?

It is interesting to note that the ancients themselves were not quite at ease in deriving Diasia from Atos. Naturally they were not troubled by difficulties as to long and short vowels, but they had their misgivings as to the connotation of the word, and they try round uneasily for etymologies of quite other significance. The Scholiast on Lucian's Timon says the word is probably derived from 'to fawn on,''to propitiate. Suidas says it comes from 'men escaped from curses by prayers.' If etymologically absurd, certainly, as will be seen, a happy guess.

Such derivations are of course only worth citing to show that even in ancient minds as regards the derivation of Diasia from Atos? misgiving lurked.

The misgiving is emphasized by the modern philologist. The derivation of Diasia with its long from Atos with its short i is scientifically improbable if not impossible. Happily another derivation that at least satisfies scientific conditions has been suggested by Mr R. A. Neil. Not only does it satisfy scientific conditions but it also confirms the view arrived at by independent investigation of the ritual and art representations of Zeus Meilichios. Mr Neil suggests that in several Greek words showing the stem Sto this stem may stand by the regular falling away of the medial a for Slao and is identical with the Latin dims, he notes, was originally a purely religious word. Such words would be the Diasia, whatever the termination may be, the Am, of Teos (p. 143). Seen in the light of this new etymology the Diasia becomes intelligible: it is the festival of curses, imprecations: it is nocturnal and associated with rites of placation and purgation, two notions inextricably linked in the mind of the ancients.

Mr P. Giles kindly tells me that a rare Sanskrit word dveshas meaning 'hate' and the like exists and phonetically would nearly correspond to the Latin dims. The corresponding form in Greek would appear as detos, unless in late Greek. But from the end of the 5th century B.C. onwards the pronunciation would be the same dtoy, and if the word survived only in ritual terms it would naturally be confused with Sios. Almost all authorities on Latin however regard the ru in dims as a suffix containing an original r as in mirus, durus etc. This view, which would be fatal the etymology of dims proposed in the text, seems supported by a statement of Servius (if the statement be accurate) on Aen. in. 235 ' Sabini et Umbri quae nos mala dira appellant,' as, though s between vowels passes in Latin and Umbrian into r, it remains an s sound in Sabine.

FromWe further understand why Meilichios seems the male double of Erinys and why his rites are associated with 'chilly gloom.' The Diasia has primarily and necessarily nothing to do with Atos, with Zeus; it has everything to do with magical curses, exorcisms and the like. The keynote of primitive ritual, it will become increasingly clear, is exorcism.

The Dian Fleece

In the light of this new derivation it is possible further to explain another element in the cult of Zeus Meilichios hitherto purposely left unnoticed, the famous Atos caiov, the supposed 'fleece of Zeus.' The Ato I think, no more the fleece of Zeus than the Diasia is his festival.

Polemon, writing at the beginning of the second century B.C., undoubtedly accepted the current derivation, and on the statement of Polemon most of our notices of 'the fleece of Zeus 'appear to be based. Hesychius writes thus: 'The fleece of Zeus: they this expression when the victim has been sacrificed to Zeus, and those who were being purified stood on it with their left foot. Some say it means a great and perfect fleece. But Polemon says it is the fleece of the victim sacrificed to Zeus.

But Polemon is by no means infallible in the matter of etymology, though invaluable as reflecting the current impression of his day. Our conviction that the Atos is necessarily 'the fleece of Zeus' is somewhat loosened when we find that this fleece was by no means confined to the ritual of Zeus, arid in so far as it was connected with Zeus, was used in the ritual only of a Zeus who bore the titles Meilichios and Ktesios. Suidas expressly states that

'they sacrifice to Meilichios and to Zeus Ktesios and they keep the fleeces of these (victims) and call them "Dian," and they use them when they send out the procession in the month of Skirophorion, and the Dadouchos at Eleusis uses them, and others use them for purifications by strewing them under the feet of those who are polluted.'

It is abundantly clear that Zeus had no monopoly in the fleece supposed to be his; it was a sacred fleece used for purification ceremonies in general. He himself had taken over the cult of Meilichios, the Placable One, the spirit of purification; we conjecture that he had also taken over the fleece of purification.

Final conviction comes from a passage in the commentary of Eustathius on the purification of the house of Odysseus after slaying of the suitors. Odysseus purges his house by two things, first after the slaying of the suitors by water, then after the hanging of the maidens by fire and brimstone. His method of purifying is a simple and natural one, it might be adopted to-day in the disinfecting of a polluted house. This Eustathius notes, and contrasts it with the complex magical apparatus in use among the ancients and very possibly still employed by the pagans of his own day. He comments as follows:

'The Greeks thought such pollutions were purified by being "sent away."

Some describe one sort of purifications some others, and these purifications they carried out of houses after the customary incantations and they cast them forth in the streets with averted faces and returned without looking backwards. But the Odysseus of the poet does not act thus, but performs a different and a simpler act, for he says:

"Bring brimstone, ancient dame, the cure of ills, and bring me fire That I the hall may fumigate."'

In the confused fashion of his day and of his own mind Eustathius sees there is a real distinction but does not recognise wherein it lies. He does not see that Homer's purification is actual, physical, rational, not magical. He goes on : 'Brimstone is a sort of incense which is reputed to cleanse pollutions. Hence the poet distinguishes it, calling it "cure of ills." In this passage there are none of the incantations usual among the ancients, nor is there the small vessel in which the live coals were carried and thrown away vessel and all backwards.'

What half occurs to Eustathius and would strike any intelligent modern observer acquainted with ancient ritual is that the purification of the house of Odysseus is as it were scientific; there is none of the apparatus of magical 'riddance.' Dimly and darkly he puts a hesitating finger on the cardinal difference between the religion of Homer and that of later (and earlier) Greece, that Homer is innocent, save for an occasional labelled magician, of magic. The Archbishop seems to feel this as something of a defect, a shortcoming. He goes on:

'It must be understood that purifications were effected not only as has just been described, by means of sulphur, but there are also certain plants that were useful for this purpose; at least according to Pausanias there is verbena, a plant in use for purification, and the pig was sometimes employed for such purposes, as appears in the Iliad!

This mention of means of purification in general brings irresistibly to the mind of Eustathius a salient instance, the very fleece we are discussing. He continues:

'Those who interpret the word say that they applied the term to the fleece of the animal that had been sacrificed to Zeus Meilichios in purifications at the end of the month of Maimakterion when they performed the Sendings and when the castings out of pollutions at the triple ways took place: and they held in their hands a sender which was they say the kerukeion, the attribute of Hermes, and from a sender of this sort, pompos, and from the Slav, the fleece called "Dian," they get the word divine sending.'

From this crude and tentative etymological guessing two important points emerge. Eustathius does not speak of the 'fleece of Zeus' but of the Dian or perhaps we may translate divine fleece. This loosens somewhat the connection of the fleece with Zeus, as the adjective could be used of anything divine or even magical in its wonder and perfection.

The explanation of the strange word to which Eustathius at the close of his remarks piously reverts, is still accredited by modern lexicons. The middle form is the most usual means, we are told, 'to avert threatened evils by offerings to Zeus.

The word dims is charged with magic, and this lives on in the Greek word 09 which is more magical than divine. It has that doubleness, for cursing and for blessing, that haunts all inchoate religious terms. The fleece is not divine in our sense, not definitely either for blessing or for cursing; it is taboo, it is 'medicine,'it is magical. As magical medicine it had power to purity, i.e. in the ancient sense, not to cleanse physically or purge morally, but to rid of evil influences, of ghostly infection.

Magical fleeces were of use in ceremonies apparently the most diverse, but at the bottom of each usage lies the same thought, that the skin of the victim has magical efficacy as medicine against impurities. Dicaearchus tells us that at the rising of the dog-star, when the heat was greatest, young men in the flower of their age and of the noblest families went to a cave called the sanctuary of Zeus Aktaios, and also (very significantly it would seem) called the Cheironion; they were girded about with fresh fleeces of triple wool. Dicaearchus says that this was because it was so cold on the mountain; but if so, why must the fleeces be fresh Zeus Aktaios, it is abundantly clear, has taken over the cave of the old Centaur Cheiron; the magic fleeces, newly slain because all 'medicine' must be fresh, belong to his order as they belonged to the order of Meilichios.

Again we learn that whoever would take counsel of the oracle of Amphiaraos must first purify himself, and Pausanias himself adds the explanatory words, 'Sacrificing to the god is a ceremony of purification.' But the purification ceremony did not, it would appear, end with the actual sacrifice, for he explains,

'Having sacrificed a ram they spread the skin beneath them and go to sleep, awaiting the revelation of a dream'

Here again, though the name is not used, we have a magic fleece with purifying properties. It is curious to note that Zeus made an effort to take over the cult of Amphiaraos, as he had taken that of Meilichios; we hear of a Zeus Amphiaraos, but the attempt was not a great success; probably the local hero Amphiaraos, himself all but a god, was too strong for the Olympian.

The results of our examination of the festival of the Diasia are then briefly this. The cult of the Olympian Zeus has over-laid the cult of a being called Meilichios, a being who was figured as a snake, who was a sort of Ploutos, but who had also some of the characteristics of an Erinys; he was an avenger of kindred blood, his sacrifice was a holocaust offered by night, his festival a time of 'chilly gloom.'A further element in his cult was a magical fleece used in ceremonies of purification and in the service of heroes. The cult of Meilichios is unlike that of the Olympian Zeus as described in Homer, and the methods of purification characteristic of him wholly alien. The name of his festival means 'the ceremonies of imprecation.

The next step in our investigation will be to take in order certain well-known Athenian festivals, and examine the ceremonies that actually took place at each. In each case it will be found that, though the several festivals are ostensibly consecrated to various Olympians, and though there is in each an element of prayer and praise and sacrificial feasting such as is familiar to us in Homer, yet, when the ritual is closely examined, the main part of the ceremonies will be seen to be magical rather that what we should term religious. Further, this ritual is addressed, in so far as it is addressed to any one, not to the Olympians of the upper air, but to snakes and ghosts and underworld beings; its main gist is purification, the riddance of evil influences, this riddance being naturally prompted not by cheerful confidence but by an ever imminent fear.

In the pages that follow but little attention will be paid to the familiar rites of the Olympians, the burnt sacrifice and its attendant feast, the dance and song; our whole attention will be focussed on the rites belonging to the lower stratum. This course is adopted for two reasons. First, the rites of sacrifice as described by Homer are simple and familiar, needing but little elucidation and having already received superabundant commentary, whereas the rites of the lower stratum are often obscure and have met with little attention. Second, it is these rites of purification belonging to the lower stratum, primitive and barbarous, even repulsive as they often are, that furnished ultimately the material out of which 'mysteries'were made mysteries which, as will be seen, when informed by the new spirit of the religions of Dionysos and Orpheus, lent to Greece its deepest and most enduring religious impulse.

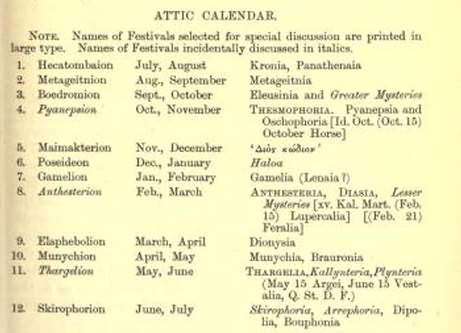

ATTIC CALENDAR

NOTE. Names of Festivals selected for special discussion are printed in large type. Names of Festivals incidentally discussed in italics.

The Athenian official calendar began in the month Hecatombaion (July August) at the summer's height. In it was celebrated the great festival of the Panathenaia, whose very name marks its political import. Such political festivals, however magnificent and socially prominent, it is not my purpose to examine; concerning the gist of primitive religious conceptions they yield us little. The Panathenaia is sacred rather to a city than a goddess. Behind the Panathenaia lay the more elementary festival of the Kronia, which undoubtedly took its name from the faded divinity Kroiios; but of the Kronia the details known are not adequate for its fruitful examination.

A cursory glance at the other festivals noted in our list shows that some, though not all, gave their names to the months in which they were celebrated, and (a fact of high significance) shows also that with one exception, the Dionysia, these festivals are not named after Olympian or indeed after any divinities. Metageitnia, the festival of 'changing your neighbours,'is obviously social or political. The Eleusinia are named after a place, so are the Munychia and Brauronia. The Thesmophoria, Oschophoria, Skirophoria and Arrephoria are festivals of carrying something; the Anthesteria, Kallynteria, Plynteria festivals of persons who do something; the Haloa a festival of threshing-floors, the Thargelia of first-fruits, the Bouphonia of ox-slaying, the Pyanepsia of bean-cooking. In the matter of nomenclature the Olympians are much to seek.

The festivals in the table appended are arranged according to the official calendar for convenience of reference, but it should be noted that the agricultural year, on which the festivals primarily depend, begins in the autumn with sowing, i.e. in Pyanepsion. The Greek agricultural year fell into three main divisions, the autumn sowing season followed by the winter, the spring with its first blossoming of fruits and flowers beginning in Anthesterion, and the early summer harvest beginning in Thargelion, the month of first-fruits; to this early harvest of grain and fruits was added with the coming of the vine the vintage in Boedromion, and the gathering in of the later fruits, e.g. the fig. All the festivals fall necessarily much earlier than the dates familiar to us in the North. In Greece to-day the wheat harvest is over by the middle or end of June.

No attempt will be made to examine all the festivals, for two practical reasons, lack of space and lack of material; but fortunately for us we have adequate material for the examination of one characteristic festival in each of the agricultural seasons, the Thesmophoria for autumn, the Anthesteria for spring, the Thargelia for early summer, and in each case the ceremonies of the several seasons can be further elucidated by the examination of the like ceremonies in the Roman calendar. To make clear the superposition of the two strata*, which for convenience'sake may be called Olympian and chthonic, the Diasia has already been examined. In the typical festivals now to be discussed a like superposition will be made apparent, and from the detailed examination of the lower chthonic stratum it will be possible to determine the main outlines of Greek religious thought on such essential points as e.g. purification and sacrifice.

As regards the ethnography of these two strata, I accept Prof. Eidgeway's view that the earlier stratum, which I have called chthonic, belongs to the primitive population of the Mediterranean to which he gives the name Pelasgian; the later stratum, to which belongs the manner of sacrifice I have called 'Olympian,' is characteristic of the Achaean population coming from the North. But, as I have no personal competency in the matter of ethnography and as Prof. Kidgeway's second volume is as yet unpublished, I have thought it best to state the argument as it appeared to me independently, i.e. that there are two strata in religion, one primitive, one later. I sought for many years an ethnographical clue to this stratification, but sought in vain.

It would perhaps be more methodical to begin the investigation with the autumn, with the sowing festival of the Thesmophoria, but as the Thesmophoria leads more directly to the consummation of Greek religion in the Mysteries it will be taken last. The reason for this will become more apparent in the further course of the argument. We shall begin with the Anthesteria.