|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER VIII.

DIONYSOS.

Dionysos An Immigrant Thracian

Dionysos and the Bessi | Dionysos in the Bacchae | Dionysos a Phrygio-Thracian | Dionysos and Nysa | The Satyrs | Satyrs and Centaurs | The Maenads | Dionysos Liknites | Dionysos Son Of Semele | Semele as Keraunia | Dionysos Son of Zeus | Bromios, Braites, Sabazios | Tragedy the Spelt-song | Cereal Intoxicants | The Coming of the Vine | Dionysos as Dendrites | Dionysos as Bull-god | Dithyrambos and the Dithyramb | The Thriae

So far the formula for Greek theology has been, 'Man makes the gods in his own image.' Mythological development has proceeded on lines perfectly normal, natural, intelligible. In so far as we understand humanity we can predicate divinity. The gods are found to be merely magnified men, on the whole perhaps better but with frequent lapses into worse, quot homines tot sententiae, quot sententiae tot dei.

"As man grew more civilized, his image, mirrored in the gods, grew more beautiful and pari passu the worship he offered to these gods advanced from 'aversion' to 'tendance'. But all along we have been conscious that something was lacking, that even these exquisite presentations of the Nymphs and the Graces, the Mother and the Daughter, are really rather human than divine, that their ritual, whether of ignorant and cruel 'aversion' or of genial 'tendance' was scarcely in our sense religious. These perfect Olympians and even these gracious Earth-goddesses are not really Lords over man's life who made them, they are not even ghosts to beckon and threaten, they are lovely dreams, they are playthings of his happy childhood, and when full-grown he comes to face realities, from kindly sentiment he lets them lie unburied in the lumber-room of his life.

Just when Apollo, Artemis, Athene, nay even Zeus himself, were losing touch with life and reality, fading and dying of their own luminous perfection, there came into Greece a new religious impulse, an impulse really religious, the mysticism that is embodied for us in the two names Dionysos and Orpheus. The object of the chapters that follow is to try and seize, with as much precision as may be, the gist of this mysticism.

Dionysos is a difficult god to understand. In the end it is only the mystic who penetrates the secrets of mysticism. It is therefore to poets and philosophers that we must finally look for help, and even with this help each man is in the matter of mysticism peculiarly the measure of his own understanding. But this ultimate inevitable vagueness makes it the more imperative that the few certain truths that can be made out about the religion of Dionysos should be firmly established and plainly set forth.

First it is certain beyond question that Dionysos was a latecomer into Greek religion, an immigrant god, and that he came from that home of spiritual impulse, the North. These three propositions are so intimately connected that they may conveniently be dealt with together.

In the face of a steady and almost uniform ancient tradition that Dionysos came from without, it might scarcely be necessary to emphasize this point but for a recent modern heresy. Anthropologists have lately recognized, and rightly, that Dionysos is in one of his aspects a nature-god, a god who comes and goes with the seasons, who has like Demeter and Kore, like Adonis and Osiris, his Epiphanies and his Recessions. They have rashly concluded that these undoubted appearances and disappearances adequately account for the tradition of his immigration, that he is merely a new-comer year by year, not a foreigner; that he is welcomed every spring, every harvest, every vintage, exorcised, expelled and slain in the death of each succeding winter. This error is beginning to filter into handbooks.

A moment's consideration shows that the actual legend points to the reverse conclusion. The god is first met with hostility, exorcised and expelled, then by the compulsion of his might and magic at last welcomed. Demeter and Kore are season-goddesses, yet we have no legend of their forcible entry. Comparative anthropology has done much for the understanding of Dionysos, but to tamper with the historical fact of his immigration is to darken counsel.

Ancient tradition must be examined, and first as to the lateness of his coming.

In Homer Dionysos is not yet an Olympian. On the Parthenon frieze he takes his place among the seated gods. Somewhere between the dates of Homer and Pheidias his entry was effected. The same is true of the indigenous Demeter, so that this argument alone is inadequate, but the fact must be noted.

The earliest monument of art

showing Dionysos as an actual denizen of Olympus is the curious

design from an amphora now in the Berlin Museum. The scene

depicted is the birth of Athene and all the divinities present

are carefully and sometimes curiously inscribed. Zeus with his

thunderbolt is seated on a splendid throne in the centre. Athene

springs from his head.

The earliest monument of art

showing Dionysos as an actual denizen of Olympus is the curious

design from an amphora now in the Berlin Museum. The scene

depicted is the birth of Athene and all the divinities present

are carefully and sometimes curiously inscribed. Zeus with his

thunderbolt is seated on a splendid throne in the centre. Athene

springs from his head.

To the right are Demeter, Artemis, Aphrodite, and last of all Apollo. To the left Eileithyia, Hermes, Hephaestos, and last Dionysos holding his great wine cup.

From the style of the inscriptions the design can scarcely date later than the early part of the sixth century. The position and grouping of the different gods is noteworthy. Of course someone must stand on the outside, but Dionysos is markedly aloof from the main action. Hermes seems to come as messenger to the furthest verge of Olympus to tell him the news. At the right, the other Northerner, Apollo, occupies the last place.

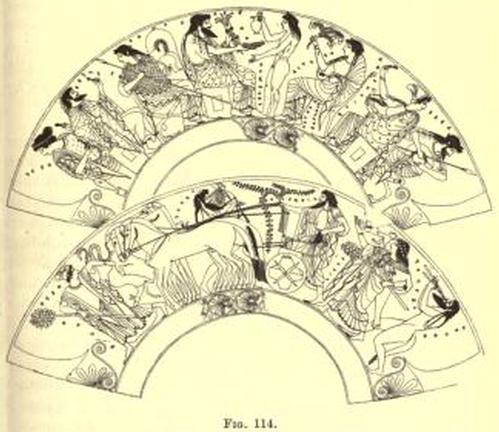

Moreover on vase-paintings substantially earlier than the Parthenon marbles the scene of his entry into Olympus is not infrequent. As we have no literary tradition of this entry, the evidence of vase-paintings is here of some importance. The design selected (fig. 114) is from a cylix signed by the potter Euxitheos and can be securely dated as a work executed about the turn of the sixth and fifth centuries B.C. On the obverse is an assembly of the Olympians all inscribed; Zeus himself with his thunderbolt and Ganymede about to fill his wine cup, Athene holding helmet and lance, Hermes with a flower, Hebe, Hestia with flower and a branch, Aphrodite with dove and flower, Ares with helmet and lance.

We might not have named them right but for their inscriptions. Hera and Poseidon are absent, Demeter not yet come. At this time the vase-painter is still free to make a certain choice, the twelve Olympians are not yet canonical. On the obverse the gods are seated waiting, and on the reverse the new god is coming in all his splendour in his chariot with vine and wine-cup in his hand. With him, characteristically, for he is never unaccompanied, come the Satyr Terpes playing on the lyre and the Maenad Thero with thyrsos and fawn and snake, and behind the chariot another Maenad Kalis with thyrsos and lion and a Satyr Terpon playing on the flute. At the close of the sixth century when Pratinas and Choirilos and Phrynichus were writing tragedies in his honour, the gates of that exclusive epic Olympus could no longer be closed against the people's god, and the potter knew it. But there had been a time of doubt and debate. We do not have these entries of Athene or Poseidon or even Hermes.

Homer is of course our first literary source and his main notice of Dionysos is so characteristic it must be quoted in full. The fact that the passage stands alone elsewhere through all Homer Dionysos is of no real account has led critics to suspect that it is of later and local origin. Be that as it may, the story glistens like an alien jewel in a bedrock of monotonous fighting. Diomede meets Glaucus in battle, but so great is the hardihood of Glaucus that Diomede fears he is one of the immortals and makes pious, prudent pause:

'I, Diomedes, will not stand 'gainst heavenly Gods in war.

Not long in life was he of old who raised 'gainst gods his hand

Strong Lycoorgos, Dryas'son. Through Nysa's goodly land

He Dionysos'Nursing Nymphs did chase, till down in fear

They cast their wands upon the ground, so sore he smote them there,

That fell king with the ox-smiter. But Dionysos fled,

And plunged him'neath the salt sea wave. Him sore discomfited

Fair Thetis to her bosom took. Great fear the god did seize.

With Lycoorgos they were wroth, those gods that dwell at ease,

And Kronos'son did make him blind, and he was not for long,

The immortal gods they hated him because he did them wrong.'

Homer is somewhat mysterious as to the end of Lycurgus 'Not long in life was he.' Sophocles is more explicit, both as to his nationality and his doom. He is a Thracian king, son of Dryas, and he was 'rock-entombed' When Antigone is going to her death the chorus sing how in like fashion others had been forced to bend beneath the yoke of the gods, Danae, Lycurgus, the sons of Phineus, Oreithyia three of them Thracians; and of Lycurgus they tell:

'He was bound by Dionysos, rock-entombed,

Dryas son, Edonian king; swiftly bloomed

His dire wrath and drooped. So was he wrought

To know his blindness and what god he sought

With gibes mad-tongued. Yea and he set his hand

To stay the god-inspired band,

To quell his women and his joyous fire

And rouse the fluting Muses into ire.'

The loss of the Lycurgus trilogy of Aeschylus is hard to bear. One scene at least must have been something like a forecast of the Bacchae of Euripides. The dialogue between Lycurgus arid the stranger-god captured and brought into his presence, is parodied by Aristophanes in the Thesmophoriazusae and the scholiast tells us that the words:

'Whence does the womanish creature come ?'

occurred in the Edonians.

Neither Homer nor Sophocles knew anything of the murder of the children. Who first piled up this fresh horror we do not know. Vase-paintings of the rather late red-figured style (middle of the fifth century B.C.) are our first sources. The punishment of sin was to the primitive mind always incomplete unless the offender was cut off with his whole family root and branch, and the murder of the children may have been an echo of the story of the mad Heracles. It is finely conceived on a red-figured krater. On the obverse is the mad Lycurgus with his children dead and dying. He swings a double axe. The 'ox-feller' of Homer is probably a double axe, not a goad. It is the typical weapon of the Thracian, and with it the Thracian women regularly on vases slay Orpheus. Through the air down upon Lycurgus swoops a winged demon of madness, probably Lyssa herself, and smites at the king with her pointed goad. To the left, behind a hill, a Maenad smites her timbrel in token of the presence of the god. On the reverse of the vase we have the peace of Dionysos who made all this madness. The god has sent his angel against Lycurgus, but no turmoil troubles him or his. About him his thiasos of Maenads and Satyrs seem to watch the scene, alert and interested but in perfect quiet.

The exact details of the fate of Lycurgus, varying as they do from author to author, are not of real importance. The essential thing, the factor which recurs in story after story, is the rage against the dominance of a new god, the blind mad fury, the swift sudden helpless collapse at the touch of a real force. This is no symbol of the coming of the spring or the gathering of the vintage. It is the mirrored image of a human experience, of the passionate vain beating of man against what is not man and is more and less than man.

The nature and essence of the new influence will be in part determined later. For the present the question that presses for solution is 'whence did it come?' 'where was the primitive jseat of the worship of Dionysos?'

The testimony of historians, from Herodotus to Dion Cassius, is uniform, and confirms the witness of Homer and Sophocles. Herodotus tells how Xerxes, when he marched through Thrace, compelled the sea tribes to furnish him with ships and those that dwelt inland to follow by land. Only one tribe, the Satrae, would suffer no compulsion, and then come the significant words: 'The Satrae were subject to no man so far as we know, but down to our own day they alone of all the Thracians are free, for they dwell on high mountains covered with woods of all kinds and snow-clad, and they are keenly warlike. These are the people that possess an oracle shrine of Dionysos and this oracle is on the topmost range of their mountains. And those among the Sati who interpret the oracle are called Bessi; it is a priestess wh utters the oracles as it is at Delphi, and the oracles are nothing more extraordinary than that.' Herodotus is not concerned with the religion of Dionysos; he does not even say that the religion of Dionysos spread southward into Greece, but he states the all-important fact that the Satrae were never conquered. They received no religion from without. Here among those splendid unconquerable savages in their mountain fastnesses was the real home of the god.

Dionysos and the Bessi

Herodotus speaks of the Bessi as though they were a kind of priestly caste among the Satrae, but Strabo knows of them as the wildest and fiercest of the many brigand tribes that dwelt on and around Mt. Haemus. All the tribes about Mt. Haemus were, he says, 'much addicted to brigandage, but the Bessi who possessed the greater part of Mt. Haemus were called brigands by brigands. They are the sort of people who live in huts in very miserable fashion, and they extend as far as Rhodope and the Paeonians.' He mentions the Bessi again as a tribe living high up on the Hebrus at the furthest point where the river is navigable, and again emphasizes their tendency to brigandage.

The evil reputation of the Bessi lasted on till Christian days, till they bowed beneath the yoke of a greater than Dionysos. Towards the end of the fourth century A.D. the good Bishop of Dacia, Niketas, carried the gospel to these mountain wolves and, if we may trust the congratulatory ode written to him by his friend Paulinus, he carried it not in vain. Paulinus celebrates the conversion of the Bessi as follows:

'Hard were their lands and hard those Bessi bold,

Cold were their snows, their hearts than snow more cold,

Sheep in the fold from roaming now they cease,

Thy fold of peace.

Untamed of war, ever did they refuse

To bow their heads to servitude's hard use,

'Neath the true yoke their necks obedient

Are gladly bent.

They who were wont with sweat and manual toil

To delve their sordid ore from out the soil

Now for their wealth with inward joy untold

Garner heaven's gold.

There where of old they prowled like savage beasts,

Now is the joyous rite of angel feasts.

The brigands'cave is now a hiding place

For men of grace.'

Thucydides in his account of Thracian affairs is silent about the Bessi and his silence surprises us. It is probably accounted for by the fact that in his days the Odrysae had complete supremacy, a supremacy that seems to have lasted down to the days of Roman domination. The autochthonous tribes were necessarily obscured. He mentions however certain mountain peoples who had retained their autonomy against Sitalkes king of the Odrysae and calls them by the collective name Dioi. Among them were probably the Bessi, for we learn from Pliny that the Bessi were known by many names, among them that of Dio-Bessi. It seems possible that to these Dio-Bessi the god may have owed one of his many names.

In the face of all this historical evidence, it is at first a little surprising to find that, in the Bacchae of Euripides, Dionysos is no Thracian. He is Theban born, and comes back to Thebes, after long triumphant wanderings not in Thrace but in Asia, through Lydia, Phrygia to uttermost Media and Arabia. On this point Euripides is explicit. In the prologue Dionysos says:

'Far now behind me lies the golden land

Of Lydian and of Phrygian far away

The wide, hot plains where Persian sun-beams play,

The Bactrian war-holds and the storm-oppressed

Clime of the Mede and Araby the blest,

And Asia all, that by the salt sea lies

In proud embattled cities, motley-wise

Of Hellene and Barbarian interwrought,

And now I come to Hellas, having taught

All the world else my dances and my rite

Of mysteries, to show me in man's sight

Manifest God.'

Dionysos is made to come from without, not as an immigrant stranger but as an exile returned. Moreover, if historical tradition be true, he is made to come from the wrong place. He comes also attended by a train of barbarian women, Asiatic not Thracian. They chant their oriental origin:

'From Asia, from the day-spring that uprises,

From Tmolus ever glorying we come,'

and again:

'Hither, fragrant of Tmolus the golden.'

Dionysos in the Bacchae

Yet Euripides wrote the play in Macedonia and must have known perfectly well that these Macedonian rites that so impressed his imagination were from Thrace; that, as Plutarch tells us,'The women called Klodones and Mimallones performed rites which were the same as those done by the Edonian women and the Thracian women about the Haemus.' He knows it perfectly well and when he is off his guard betrays his knowledge. In the epode of the third choric song he makes Dionysos come to bless Pieria and in his coming cross the two Macedonian rivers, the Axios and Lydias:

'Blessed land of Pierie,

Dionysos loveth thee,

He will come to thee with dancing,

Come with joy and mystery,

With the Maenads at his best

Winding, winding to the west;

Cross the flood of swiftly glancing

Axios in majesty,

Cross the Lydias, the giver

Of good gifts and waving green,

Cross that Father Stream of story

Through a land of steeds and glory

Rolling, bravest, fairest River

E'er of mortals seen.'

Euripides as poet can afford to contradict himself. He accepts popular tradition, too careless of it to attempt an irrelevant consistency. It matters nothing to him whence the god came. The Theban birth-place, the home-coming were essential to the human pathos of his story. But for that we should have missed the appeal to Dirce:

'Achelous'roaming daughter, Holy Dirce, virgin water, Bathed he not of old in thee The Babe of God, the Mystery?'

and again:

'Why, Blessed among Rivers,

Wilt thou fly me and deny me?

By his own joy I vow,

By the grape upon the bough,

Thou shalt seek him in the midnight, thou shalt love him even now.'

He came unto his own and his own received him not.

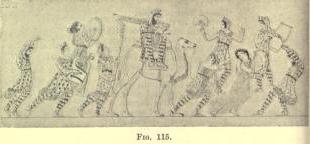

When we examine the evidence of

art, we find that the simple vase-painter accepts the fact that

Dionysos has become a Greek, and does not raise the question

whence he came. In black and early red figured designs Dionysos

is almost uniformly dressed as a Greek and attended by Greek

Maenads. Later the artist becomes more learned and dresses

Dionysos as a Thracian or occasionally as an Oriental. The

vase-painting in fig. 115, from a late aryballos in the British

Museum, has been usually interpreted as representing the Oriental

triumph of Dionysos. Rightly so, I inclii to think, because the

figure on the camel is attended not only by Orientals but by

Greek maidens playing on cymbals. Their free upward bearing

contrasts strongly with the strange abject fantastic posturings

of the Orientals. It must however distinctly borne in mind that

the figure on the camel carries no Dionysiac attributes and

cannot be certainly said to be the god.

When we examine the evidence of

art, we find that the simple vase-painter accepts the fact that

Dionysos has become a Greek, and does not raise the question

whence he came. In black and early red figured designs Dionysos

is almost uniformly dressed as a Greek and attended by Greek

Maenads. Later the artist becomes more learned and dresses

Dionysos as a Thracian or occasionally as an Oriental. The

vase-painting in fig. 115, from a late aryballos in the British

Museum, has been usually interpreted as representing the Oriental

triumph of Dionysos. Rightly so, I inclii to think, because the

figure on the camel is attended not only by Orientals but by

Greek maidens playing on cymbals. Their free upward bearing

contrasts strongly with the strange abject fantastic posturings

of the Orientals. It must however distinctly borne in mind that

the figure on the camel carries no Dionysiac attributes and

cannot be certainly said to be the god.

Dionysos a Phrygio-Thracian

The question remains why did popular tradition, accepted by Euripides and embodied occasionally in vase-paintings, point to Asia rather than to the real home, Thrace? The answer in the main is given by Strabo in his important account of the provenance of the orgiastic worships of Greece. Strabo is noting that Pindar, like Euripides, regards the rites of Dionysos as substantially the same with those performed by the Phrygians in honour of the Great Mother.' Very similar to these are,'he adds, 'the rites called Kotytteia and Bendideia, celebrated among the Thracians. Nor is it at all unlikely that, as the Phrygians themselves are colonists from the Thracians, they brought their religious rites from thence.' In a fragment of the lost seventh book he is still more explicit. He is mentioning the mountain Bernicos as formerly in possession of the Briges, and the Briges, he says, were'a Thracian tribe of which some portion went across into Asia and were called by a modified name, Phrygians.'

The solution is simple and is indeed almost a geographical necessity. If the Thracians dwelling in the ranges of Rhodope and Haemus went south at all, they would inevitably split up into two branches. The one would move westward into Macedonia, across the Axios and Lydias into Thessaly and thence downwards to Delphi, Thebes and Attica; the other eastward across the Bosporus or the Hellespont into Asia Minor. Greek colonists in Asia Minor would recognize in the orgiastic cults they found there elements akin to their own worship of Dionysos. Wise men are not slow to follow the star that leads to the east, and it was pleasanter to admit a debt to Asia Minor than to own kinship with the barbarous north. Similarity of names, e.g. Lydias and Lydia, may have helped out the illusion and most of all the Theban legend of the Phoenician Kadmos.

But mythology is too unconscious not to betray itself. Herodotus says that the Thracians worship three gods only: Ares, Dionysos and Artemis. Between Ares and Dionysos there would seem to be but little in common, but in one current myth their kinship comes out all unconsciously. It is just these unconscious revelations that are in mythology of cardinal importance. The story is that known as the 'bonds of Hera'. Hephaistos, to revenge himself for his downfall from heaven, sent to his mother Hera a golden throne with invisible bonds. The Olympians took counsel how they might free their queen. None but Hephaistos knew the secret of loosing. Ares vowed he would bring Hephaistos by force. Hephaistos drove him off with fire-brands. Force failed, but Hephaistos yielded to the seduction of Dionysos and was brought in drunken triumph back to Olympus. It was a good subject for broad comedy, and Epicharmus used it in his'Revellers or Hephaistos.' It attained a rather singular popularity in art; the subject occurs on upwards of thirty vase-paintings black and red figured.

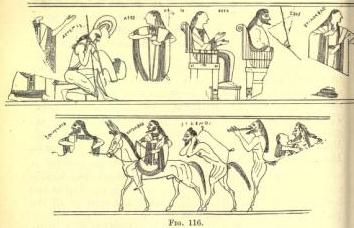

Earlier than any literary source

for the myth is unquestionably the famous Fraois vase (early

sixth century B.C.) in the Museo Civico at Florence, where the

scene is depicted in broad epic fashion and with some conscious

humour. All the figures are inscribed. Zeus is there and Hera,

seated on the splendid, fatal throne. Dionysos leads the mule on

which sits the drunken Hephaistos. Up they come into the very

presence of Zeus with three attendant Silenoi carrying

respectively a wine-skin, a flute, a woman. It is the regular

revel rout. Behind the throne of Hera crouches Ares in deep

dejection, on a sort of low stool of repentance, while Athene

looks back at him with scorn. Why are Ares and Dionysos thus set

in rivalry? Not merely because wine is mightier than war, but

because the two, Ares and Dionysos, are Thracian rivals, with

Hephaistos of Lemnos for a third. It is a bit of local mythology

transplanted later to Olympus.

Earlier than any literary source

for the myth is unquestionably the famous Fraois vase (early

sixth century B.C.) in the Museo Civico at Florence, where the

scene is depicted in broad epic fashion and with some conscious

humour. All the figures are inscribed. Zeus is there and Hera,

seated on the splendid, fatal throne. Dionysos leads the mule on

which sits the drunken Hephaistos. Up they come into the very

presence of Zeus with three attendant Silenoi carrying

respectively a wine-skin, a flute, a woman. It is the regular

revel rout. Behind the throne of Hera crouches Ares in deep

dejection, on a sort of low stool of repentance, while Athene

looks back at him with scorn. Why are Ares and Dionysos thus set

in rivalry? Not merely because wine is mightier than war, but

because the two, Ares and Dionysos, are Thracian rivals, with

Hephaistos of Lemnos for a third. It is a bit of local mythology

transplanted later to Olympus.

The diverse fates of these two Thracian gods are instructive. Ares was realized as a Thracian to the end. In Homer he is only half accepted in Olympus, he is known as a ruffian and a swashbuckler and like Aphrodite escapes to his home as soon as he is released:

'Straightway forth sprang the twain;

To savage Thrace went Ares, but Kypris with sweet smile

Hied her to her fair altar place, in pleasant Paphos'isle.'

The newly admitted gods, such as Ares and Aphrodite, are never really at home in Olympus. Dionysos, as has already been seen, has no place in the Homeric Olympus, but, once he does force an entry, his seat is far more stable. In the Oedipus Tyrannos Sophocles realizes that Dionysos and Ares are the great Theban divinities, but Ares is of slaughter and death, Dionysos of gladness and life. He makes his chorus summon Dionysos to banish Ares his fellow divinity:

'0 thou with golden mitre band,

Named for our land,

On thee in this our woe

I call, thou ruddy Bacchus all aglow

blockquote With wine and Bacchant song.

Draw nigh, thou and thy Maenad throng,

Drive from us with bright torch of blazing pine

The god unhonoured'mong the gods divine.'

Sophocles just hits the theological mark, Ares is a god but he is unhonoured of the orthodox gods, the Olympians.

Euripides too lets out the kinship with Ares. He knows of 'Harmonia, daughter of the Lord of War,'

Harmonia, bride of Kadmos, mother of Semele, and though his Dionysos is at the outset all gentleness and magic, his kingdom scarcely of this world, Teiresias knows that he is not only Teacher, Healer, Prophet, but

'of Ares'realm a part hath he.

When mortal armies mailed and arrayed

Have in strange fear, or ever blade met blade,

Fled, maddened,'tis this god hath palsied them,'

and though the panic he sends is from within not without, yet the mention is significant. Dionysos, for all his sweetness, is to the end militant, he came not to bring peace upon the earth but a sword, only in late authors his weapons are not those of Ares. On vase-paintings he is not unfrequently depicted doing on his actual armour, but Polyaenus, in the little treatise on mythological warriors with which he prefaces his Strategika, notes the secret armour of the god, the lance hidden in ivy, the fawn-skin and soft raiment for breastplate, the cymbals and drum for trumpet. To the end the god of the brigand Bessi was Lord of War.

Art tells the same tale, that the Thracian Dionysos succeeded where the equally Thracian Ares failed. Among the archaic seated gods on the frieze of the treasury of Cnidos recently discovered at Delphi Ares has found a place, but a significant one, at the very end, on a seat by himself, as though naively to mark the difference. Even on the east frieze of the Parthenon, where all is softened down to a decent theological harmony, there is just a lingering, semi-conscious touch of the same prejudice. Ares is admitted indeed, but he is not quite at home among these easy aristocratic Olympians. He is grouped with no one, he leans his arm on no one's shoulder; even his pose is a little too consciously assured to be quite confident.

Dionysos and Nysa

It is abundantly clear that the remote Asiatic origin of Dionysos is emphasized to hide a more immediate Thracian provenance. The Greeks knew the god was not home-grown, but he was so great, so good, so all-conquering, that they were forced to accept him. But they could not bear the truth, that he came from their rough north-country kinsmen the Thracians. They need not have been ashamed of these Northerners, who were as well born as and more bravely bred than themselves. Even Herodotos owns that'the nation of the Thracians is the greatest among men, except at least the Indians.'

Once fairly uprooted from his native Thracian soil, it was easy to plant Dionysos anywhere and everywhere wherever went his worshippers. His homeless splendour grows and grows till by the time of Diodorus his birthplace is completely apocryphal. In Homer, as has been seen, Nysa or as it is called Nyseion, whether it be mountain or plain, is clearly in Thrace, home of Lycurgus son of Dryas. But already in Sophocles, in the beautiful fragment preserved by Strabo, wherever it may be, it is a place touched by magic, a silent land which

'The horned lacchus loves for his dear nurse,

Where no shrill voice doth sound of any bird.'

Euripides never expressly states where he supposes Nysa to be, but the name comes to his lips coupled with the Korykian peaks on Parnassos and the leafy haunts of Olympus, so we may suppose he believed it to be northwards. As the horizon of the Greeks widened, Nysa is pushed further and further away to an ever more remote Nowhere. Diodorus with much circumstance settles it in Libya on an almost inaccessible island surrounded by the river Triton. It mattered little so long as it was a far-off happy land.

Convinced as he was of this remote African Nysa and of the great Asiatic campaign of Dionysos, it is curious to note that even Diodorus cannot rid his mind of Thrace. He knows of course the story of the Thracian Lycurgus and mentions incidentally that it was in a place called Nysion that Lycurgus set upon the Maenads and slew them, he knows too of the connection between Dionysos and Orpheus and never doubts but that Orpheus was a Thracian, a matter to be discussed later. Most significant of all, when he is speaking of the trieteric ceremonies instituted in memory of the Indian expedition, he automatically records that these were celebrated not only by Boeotians and the other Greeks but by the Thracians. Thrace is obscured by the glories of Phrygia, Lydia, Phoenicia, Arabia and Libya, but never wholly forgotten.

The Satyrs

Dionysos then, whatever his nature, is an immigrant god, a late comer, and he enters Greece from the north, from Thrace. He comes not unattended. With him are always his revel rout of Satyrs and of Maenads. This again marks him out from the rest of the Olympians; Poseidon, Athene, Apollo, Zeus himself has no such accompaniment. As man makes the gods in his own image, it may be well before we examine the nature and functions of Dionysos to observe the characteristics of his attendant worshippers, to determine who and what they are and whence they come.

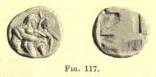

The Satyrs first they are (what

else should they, could they be?) the Satrae*; and these

Satrae-Satyrs have many traits in common with the more

mythological Centaurs. The evidence of the coins of Macedonia is

instructive. On the coins of Orreskii, a centaur, a horse -man,

bears off a woman in his arms. At Lete close at hand, with a

coinage closely resembling in style, fabric, weight the money of

the Orreskii and other Pangaean tribes, the type is the same in

content, though with an instructive difference of form a naked

Satyr or Seilenos with the hooves, ears and tail of a horse

seizes a woman round the waist. These coins are of the sixth

century B.C. Passing to Thasos, a colony of the Thracians and

like it rich in the coinage that came of gold mines, we find the

same type. On a series of coins that range from circ. 500 411

B.C. we have again the Satyr or Seilenos bearing off the woman.

An instance, for clearness'sake one of comparatively late date,

is given in fig. 117.

The Satyrs first they are (what

else should they, could they be?) the Satrae*; and these

Satrae-Satyrs have many traits in common with the more

mythological Centaurs. The evidence of the coins of Macedonia is

instructive. On the coins of Orreskii, a centaur, a horse -man,

bears off a woman in his arms. At Lete close at hand, with a

coinage closely resembling in style, fabric, weight the money of

the Orreskii and other Pangaean tribes, the type is the same in

content, though with an instructive difference of form a naked

Satyr or Seilenos with the hooves, ears and tail of a horse

seizes a woman round the waist. These coins are of the sixth

century B.C. Passing to Thasos, a colony of the Thracians and

like it rich in the coinage that came of gold mines, we find the

same type. On a series of coins that range from circ. 500 411

B.C. we have again the Satyr or Seilenos bearing off the woman.

An instance, for clearness'sake one of comparatively late date,

is given in fig. 117.

This interchange of types, Satyr and Centaur, is evidence about which there can be no mistake. Satyr and Centaur, slightly diverse forms of the horse-man, are in essence one and the same. Nonnus is right: 'the Centaurs are of the blood of the shaggy Satyrs.' It remains to ask who are the Centaurs?

There are few mythological figures about which more pleasant baseless fancies have been woven; woven irresponsibly, because mythologists are slow to face solid historical fact; woven because, intoxicated by comparative philology, they refuse to seek for the origin of a myth in its historical birthplace. The Centaurs, it used to be said, are Vedic Gandharvas, cloud-demons. Mythology now-a-days has fallen from the clouds, and with it the Centaurs. They next became mountain torrents, the offspring of the cloud that settles on the mountain top. The Centaurs have possession of a wine-cask, the imprisoned forces of the earth's fertility are left in charge of the genius of the mountain. The cask is opened, this is the unlocking of the imprisoned forces at the approach of Herakles, the sun in spring, and this unlocking is the signal for the mad onset of the Centaurs, the wild rush of the torrents. Of the making of such mythology truly there is no end.

Homer knew quite well who the opponents of Peirithoos were, not cloud-demons, not mountain torrents, but real wild men (cfrrjpes), as real as the foes they fought with. He tells of the heroes Dryas, father of Lycurgus, and Peirithoos and Kaineus:

'Mightiest were they, and with the mightiest fought,

With wild men mountain-haunting.'

No one has, so far as we know, reduced the mighty Peirithoos, Dryas and Lycurgus to mountain torrents or sun myths. Why are their mighty foes to be less human?

Again in the Catalogue of the Ships we are told how Peirithoos

Took vengeance on the shaggy mountain-men,

Drave them from Pelion to the Aithikes far.'

In the name of common sense, did Peirithoos expel a stormcloud or a mountain torrent and force it to leave Pelion and settle elsewhere? The vengeance of Peirithoos is simply the expulsion of one wild tribe by another.

In these passages from the Iliad the foes of Peirithoos are simply a tribe of wild men, Pheres. In the Odyssey, Homer calls these same foes by the name Kentauri, and implies that they are non-human. Speaking of the peril of 'honey-sweet wine' he says:

'Thence'gan the feud'twixt Centaurs and mankind.'

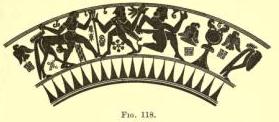

For the right understanding of this later non-humanity of the Centaurs the development of their art type is of paramount importance.

We are apt to think of the Centaurs exclusively somewhat as they appear on the metopes of the Parthenon, i.e. as splendid horses with the head and trunk of a man. By the middle of the fifth century B.C. in knightly horse-loving Athens the horse form had got the upper hand. In archaic representations the reverse is the case. The Centaurs are in art what they are in reality, men with men's legs and feet, but they are shaggy mountain men with some of the qualities and habits of beasts; so to indicate this in a horse-loving country they have the hind-quarters of a horse awkwardly tacked on to their human bodies.

A good example is the

vase-painting in fig. 118 from an early black-figured lekythos in

the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Vases of this style cannot be

dated later than the beginning of the sixth century B.C. and may

be somewhat earlier. The scene represented is the fight of

Herakles with the Centaurs. To the left is a Centaur holding in

his right hand a branch, the primitive weapon of a primitive

combatant. He is figured as a complete man with a horse-trunk

appended. In the original drawing the horse-trunk is made more

obviously an extra appendage from the fact that the human body is

painted red and the horse-trunk black. Herakles too is a fighter

with rude weapons; he carries his club, which in this case is

plainly what its Greek name indicates, a rough hewn trunk or

branch or possibly root of a tree. The remainder of the design is

not so clear and does not affect the present argument. The man

with the sword to the right is probably lolaos. The object

surmounted by the eagles I am quite unable to explain.

A good example is the

vase-painting in fig. 118 from an early black-figured lekythos in

the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Vases of this style cannot be

dated later than the beginning of the sixth century B.C. and may

be somewhat earlier. The scene represented is the fight of

Herakles with the Centaurs. To the left is a Centaur holding in

his right hand a branch, the primitive weapon of a primitive

combatant. He is figured as a complete man with a horse-trunk

appended. In the original drawing the horse-trunk is made more

obviously an extra appendage from the fact that the human body is

painted red and the horse-trunk black. Herakles too is a fighter

with rude weapons; he carries his club, which in this case is

plainly what its Greek name indicates, a rough hewn trunk or

branch or possibly root of a tree. The remainder of the design is

not so clear and does not affect the present argument. The man

with the sword to the right is probably lolaos. The object

surmounted by the eagles I am quite unable to explain.

Satyrs and Centaurs

The

next stage in the development of the Centaur is seen in the

archaic gem from the British Museum in fig. 120. Here the

noticeable point is that the Centaur, though he has still the

body of a man, is beginning to be more of a horse. He has hoofs

for feet. He is behaving just like the Satyr on the coin in fig.

117, or the aggressor on the Fracois vase (fig. 116), he is

carrying off a woman. It is the last step in the transition to

the Centaur of the Parthenon, i.e. the horse with head and trunk

of a man. Between Satyr and Centaur the sole difference is this:

the Centaur, primarily a wild man, became more and more of a

horse, the Satyr resisted the temptation and remained to the end

what he was at the beginning, a wild man, with horse adjuncts of

ears, tail and occasionally hoofs. Greek art, as has been already

seen in discussing the Gorgon, was liberal in its experiments

with monster forms, the horse Medusa failed, the horse Centaur

prevailed.

The

next stage in the development of the Centaur is seen in the

archaic gem from the British Museum in fig. 120. Here the

noticeable point is that the Centaur, though he has still the

body of a man, is beginning to be more of a horse. He has hoofs

for feet. He is behaving just like the Satyr on the coin in fig.

117, or the aggressor on the Fracois vase (fig. 116), he is

carrying off a woman. It is the last step in the transition to

the Centaur of the Parthenon, i.e. the horse with head and trunk

of a man. Between Satyr and Centaur the sole difference is this:

the Centaur, primarily a wild man, became more and more of a

horse, the Satyr resisted the temptation and remained to the end

what he was at the beginning, a wild man, with horse adjuncts of

ears, tail and occasionally hoofs. Greek art, as has been already

seen in discussing the Gorgon, was liberal in its experiments

with monster forms, the horse Medusa failed, the horse Centaur

prevailed.

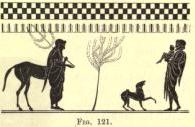

The Parthenon type of the Centaur, the type in which the horse-form is predominant, obtains later in red-figured vase-paintings for all Centaurs save one, the virtuous Cheiron. Cheiron always keeps his human feet and legs and often wears a decent cloak to mark his gentle civilized citizenship. Pausanias when examining the chest of Kypselos at Olympia, a monument dedicated in the seventh century B.C., noted this peculiarity: 'And the Centaur has not all his feet like a horse, but the front feet are the feet of a man/ Pindar does definitely in the case of Cheiron identify jijp and Kevravpos, but art kept for Cheiron the more primitive and human type to emphasize his humanity, for he is the trainer of heroes, the utterer of wise saws, the teacher of all gentle arts of music and medicine, he has the kind heart of a man.

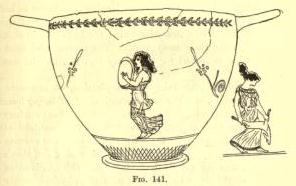

The charming little design in fig.

121 is from an oinochoe in the British Museum. Though the

technique is black-figured the delicate soft style is archaistic

rather than archaic and the vase is probably not older than the

middle of the fifth century B.C. The good Cheiron is a quaint

blend of horse and middle-aged citizen. The tree branch he still

carries looks back to the primitive habits he has left far

behind, and the little tree in front marks the woodland home. But

there is nothing shaggy about his neat decorous figure. Even the

dog who used to go hunting with him is now alert to give a

courteous welcome to the guest. A father is bringing his child, a

little miniature copy of himself, to be reared in the school of

Cheiron. Father and son are probably Peleus and Achilles, but the

child might be Jason or even Asklepios. It is the good Centaur

only who concerns us. How has he of the mountains, fierce and

untameable, come to keep a preparatory school for young heroes ?

The answer to this question is interesting and instructive.

The charming little design in fig.

121 is from an oinochoe in the British Museum. Though the

technique is black-figured the delicate soft style is archaistic

rather than archaic and the vase is probably not older than the

middle of the fifth century B.C. The good Cheiron is a quaint

blend of horse and middle-aged citizen. The tree branch he still

carries looks back to the primitive habits he has left far

behind, and the little tree in front marks the woodland home. But

there is nothing shaggy about his neat decorous figure. Even the

dog who used to go hunting with him is now alert to give a

courteous welcome to the guest. A father is bringing his child, a

little miniature copy of himself, to be reared in the school of

Cheiron. Father and son are probably Peleus and Achilles, but the

child might be Jason or even Asklepios. It is the good Centaur

only who concerns us. How has he of the mountains, fierce and

untameable, come to keep a preparatory school for young heroes ?

The answer to this question is interesting and instructive.

Prof. Ridgeway has shown that in the mythology of the Centaurs we have a reflection of the attitude of mind of the conquerors to the conquered. This attitude is, all the world over, a double one. The conquerors are apt to regard the conquered with mixed feelings, mainly, it is true, with hatred and aversion, but in part with reluctant awe.' The conquerors respect the conquered as wizards, familiar with the spirits of the land, and employ them for sorcery, even sometimes when relations are peaceable employ them as foster-fathers for their sons, yet they impute to them every evil and bestial characteristic and believe them to take the form of wild beasts. The conquered for their part take refuge in mountain fastnesses and make reprisals in the characteristic fashion of Satyrs and Centaurs by carrying off the women of their conquerors.'

Nonnus is again right, it was jealousy that gave to the Satyrs their horns, their manes, tusks and tails, but not, as Nonnus supposed, the jealousy of Hera, but of primitive conquering man who gives to whatever is hurtful to himself the ugly form that utters and relieves his hate. It should not be hard for us to realize this impulse; our own devil, with horns and tail and hoofs, died hard and recently.

Most instructive of all as to the real nature of the Centaurs and their close analogy to the Satrai-Satyroi is the story of the opening of the wine cask. Pindar tells how

'Then when the wild men knew

The scent of honeyed wine that tames men's souls,

Straight from the board they thrust the white milk-bowls

With hurrying hands, and of their own will flew

To the horns of silver wrought,

And drank and were distraught.'

Storm-clouds and mountain torrents, nay even four-footed beasts do not get drunk, the perfume of wine is for the subduing of man alone. The wild things (ffipes) are all human,'they thrust with their hands.'

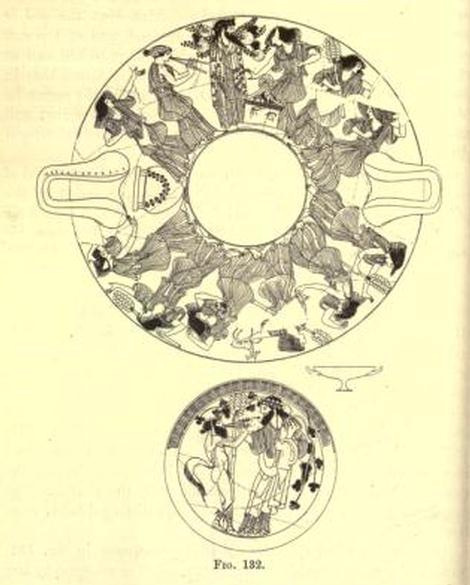

The scene is a favourite one on

vases. One of the earliest representations is given in fig. 122

from a skyphos in the Louvre. It dates about the beginning of the

sixth century B.C. The scene is the cave of the Centaur Pholos.

The great pithos or wine jar is open. Pholos himself has a large

wine-cup in his hand. Pholos is sober still, he is a sort of

Cheiron, but not so the rest. They are mad with drink and are

hustling and fighting in wild confusion. Herakles comes out and

tries to restore order. Wine has come for the first time to a

primitive population unused to so strong an intoxicant. The

result is the same all over the world. A like notion comes out in

the popular myth of the wedding feast of Peirithoos; the Centaurs

taste wine and fall to fighting and in Satyr fashion seek to

ravish the bride. These stories are of paramount importance

because they point the analogy between two sets of primitive

worshippers of Dionysos, the Centaurs and the Satrai-Satyroi.

The scene is a favourite one on

vases. One of the earliest representations is given in fig. 122

from a skyphos in the Louvre. It dates about the beginning of the

sixth century B.C. The scene is the cave of the Centaur Pholos.

The great pithos or wine jar is open. Pholos himself has a large

wine-cup in his hand. Pholos is sober still, he is a sort of

Cheiron, but not so the rest. They are mad with drink and are

hustling and fighting in wild confusion. Herakles comes out and

tries to restore order. Wine has come for the first time to a

primitive population unused to so strong an intoxicant. The

result is the same all over the world. A like notion comes out in

the popular myth of the wedding feast of Peirithoos; the Centaurs

taste wine and fall to fighting and in Satyr fashion seek to

ravish the bride. These stories are of paramount importance

because they point the analogy between two sets of primitive

worshippers of Dionysos, the Centaurs and the Satrai-Satyroi.

To these Satrai-Satyroi we must now return. It is now sufficiently clear that, whatever they became to a later imagination, to Homer and Pindar and the vase-painters these horsemen, these attendants of Dionysos, were not fairies, not 'spirits of vegetation' though from such they may have borrowed many traits, but the representatives of an actual primitive population. They owe their monstrous form, their tails, their horses' ears and hoofs, not to any desire to express 'powers of fertilization' but to the malign imagination of their conquerors. They are not incarnations of a horse-god Dionysos such a being never existed they are simply Satrai. It is not of course denied that they ultimately became mythological, that is indeed indicated by the gradual change of form. As a rule the Greek imagination tends to anthropomorphism, but here we have a reverse case. By lapse of time and gradual oblivion of the historical facts of conquest, what was originally a primitive man developes in the case of the Centaurs into a mythological horse-demon.

The Satyrs undergo no such change, they remain substantially human. The element of horse varies but is never predominant.

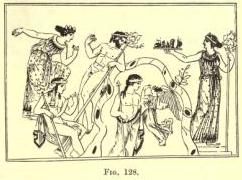

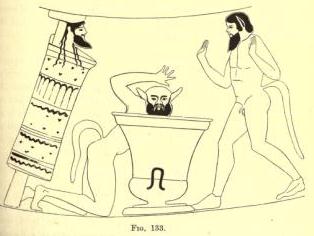

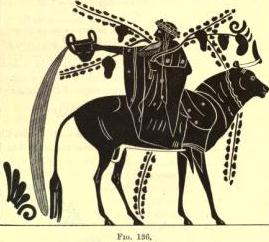

The form in which there is most

horse is well shown in fig. 123. This picture is from the reverse

of the cylix in the Wlirzburg Museum, on which is depicted the

feast of Phineus already discussed. The fact is worth noting that

both representations come from a Thracian cycle of mythology.

Phineus is a Thracian hero, Dionysos a Thracian god. Dionysos

stands in a chariot to which are yoked a lion and a stag. By his

side is a woman, probably a goddess, but whether Ariadne or

Semele cannot certainly be determined, nor for the present

argument does it matter. The god has stopped to water his steeds

at a fountain. Satyrs attend him, one is drawing water from the

well basin, another clambers on the lion's back. Some maidens

have bathed at the fountain, and are resting under a palm tree,

one is just struggling back into her clothes. Two prying Satyrs

look on with evil in their hearts. They are wild men with shaggy

bodies, rough hair, horses'ears and tails, and they have the

somewhat exceptional addition of hoofs; the human part of them is

closely analogous to the shaggy Centaurs of fig. 122.

The form in which there is most

horse is well shown in fig. 123. This picture is from the reverse

of the cylix in the Wlirzburg Museum, on which is depicted the

feast of Phineus already discussed. The fact is worth noting that

both representations come from a Thracian cycle of mythology.

Phineus is a Thracian hero, Dionysos a Thracian god. Dionysos

stands in a chariot to which are yoked a lion and a stag. By his

side is a woman, probably a goddess, but whether Ariadne or

Semele cannot certainly be determined, nor for the present

argument does it matter. The god has stopped to water his steeds

at a fountain. Satyrs attend him, one is drawing water from the

well basin, another clambers on the lion's back. Some maidens

have bathed at the fountain, and are resting under a palm tree,

one is just struggling back into her clothes. Two prying Satyrs

look on with evil in their hearts. They are wild men with shaggy

bodies, rough hair, horses'ears and tails, and they have the

somewhat exceptional addition of hoofs; the human part of them is

closely analogous to the shaggy Centaurs of fig. 122.

The Satyrs are not pleasant to contemplate; they are ugly in form and degraded in habits, and but for a recent theory it might not be needful to emphasize so strongly their nature and functions. This theory, which has gained wide and speedy popularity, maintains that the familiar horse-men of black and red figured vases are not Satyrs at all. The Satyrs, we are told, are goat-men, the horse-men of the vases are Seilenoi. This theory, if true, would cut at the root of our whole argument. To deny the identity of the horse-men with the Satyrs is to deny their identity with the Satrai, i.e. with the primitive population who worshipped Dionysos.

Why then, with the evidence of countless vase-paintings to support us, may we not call the horse-men who accompany Dionysos Satyrs? Because, we are told, tragedy is the goat-song, the goat-song gave rise to the Satyric drama, hence the Satyrs must be goat-demous, hence they cannot be horse-demons, hence the horse-demons of vases cannot be Satyrs, hence another name must be found for them. On the Francois-vase (fig. 116) the horse-demons are inscribed Seilenoi, hence let the name Seilenoi be adopted for all horse-demons. Be it observed that the whole complex structure rests on the philological assumption that tragedy means the goat-song. What tragedy really does or at least may mean will be considered later; for the present the point is only raised because I hold to the view now discredited that the familiar throng of idle disreputable vicious horse-men who constantly on vases attended Dionysos, who drink and sport and play and harry women, are none other than Hesiod's 'race Of worthless idle Satyrs.'

That they are also called Seilenoi I do not for a moment deny. In different lands their names were diverse.

The Maenads

It is refreshing to turn from the dissolute crew of Satyrs to the women-attendants of Dionysos, the Maenads. These Maenads are as real, as actual as the Satyrs; in fact more so, for no poet or painter ever attempted to give them horses'ears and tails. And yet, so persistent is the dislike to commonplace fact, that we are repeatedly told that the Maenads are purely mythological creations and that the Maenad orgies never appear historically in Greece.

It would be a mistake to regard the Maenads as the mere female correlatives of the Satyrs. The Satyrs, it has been seen, are representations of a primitive subject people, but the Maenads do not represent merely the women of the same race. Their name is the corruption of no tribal name, it represents a state of mind and body, it is almost a cultus-epithet. Maenad means of course simply 'mad woman,' and the Maenads are the women-worshippers of Dionysos of whatever race, possessed, maddened or, as the ancients would say, inspired by his spirit.

Maenad is only one, though perhaps the most common, of the many names applied to these worshipping women. In Macedonia Plutarch tells us they were called Mimallones and Klodones, in Greece, Bacchae, Bassarides, Thyiades, Potniades and the like.

Some of the titles crystallized into something like proper names, others remained consciously adjectival. At bottom they all express the same idea, women possessed by the spirit of Dionysos. Plutarch in his charming discourse on Superstition tells how when the difchyrambic poet Timotheos was chanting a hymn to Artemis he addressed the daughter of Zeus thus:

'Maenad, Thyiad, Phoibad, Lyssad.'

The titles may be Englished as Mad One, Rushing One, Inspired One, Raging One. Cinesias the lyric poet, whose own songs were doubtless couched in language less orgiastic, got up and said: 'I wish you may have such a daughter of your own.' The story I is instructive on two counts. It shows first that Maenad and Thyiad were at the date of Timotheos so adjectival, so little crystallized into proper names, that they could be applied not merely to the worshippers of Dionysos, but to any orgiastic divinity, and second the passage is clear evidence that educated people, towards the close of the fifth century B.C., were beginning to be at issue with their own theological conceptions. Cultus practices however, and still more cultus epithets, lay far behind educated opinion. It is fortunately possible to prove that the epithet Thyiad certainly and the epithets Phoibad and Maenad probably, were applied to actually existing historical women. The epithet Lyssad, which means'raging mad,'was not likely to prevail out of poetry. The chorus in the Bacchae call themselves'swift hounds of raging Madness,'but the title was not one that would appeal to respectable matrons.

We begin with the Thyiades. It is at Delphi that we learn most of their nature and worship, Delphi where high on Parnassos Dionysos held his orgies. Thus much even Aeschylus, though he is'all for Apollo,'cannot deny. To this he makes the priestess in her ceremonial recitation of local powers bear almost reluctant witness:

'You too I salute,

Ye nymphs about, Kory Ida's caverned rock,

Kindly to birds, haunt of divinities.

And Bromios, I forget not, holds the place,

Since first to war he led his Bacchanals,

And scattered Pentheus, like a riven hare.'

Aeschylus, intent on monotheism, would fain know only the two divinities who were really one, i.e. Zeus and

'Loxias utterer of his father's will,'

the Father and the Son, these and the line of ancient Earth-divinities to whom they were heirs. But religious tradition knew of another immigrant, Dionysos, and Aeschylus cannot wholly ignore him. On the pediments of the great temple were sculptured at one end, Pausanias tells us, Apollo, Artemis, Leto and the Muses, and at the other'the setting of the sun and Dionysos with his Thyiad women.' The ritual year at Delphi was divided, as will later be seen, between Apollo and Dionysos.

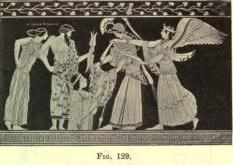

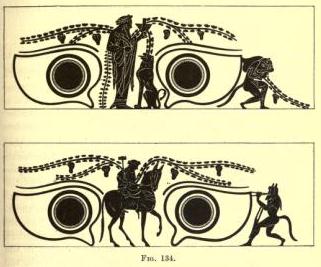

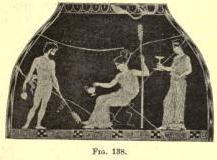

The vase-painting in fig. 124 from a krater in the Hermitage Museum at St Petersburg is a brief epitome of the religious history of Delphi, marking its three strata. In the foreground is the omphalos of Gaia covered with fillets:

'First in my prayer before all other gods

. I call on Earth, primaeval prophetess,'

Gaia, of whom her successors Themis and Phoebe are but by-forms. Higher up in the picture are other divinities superimposed on this primitive Earth-worship. Apollo and Dionysos clasp hands while about them is a company of Maenads and Satyrs. It is perhaps not quite certain which is regarded as the first comer, but the balance is in favour of Dionysos as the sanctuary is already peopled with his worshippers. His dress has something of Oriental splendour about it as compared with the Hellenic simplicity of Apollo. Each carries his characteristic wand, Apollo a branch of bay, Dionysos a thyrsos.

In this vase-painting, which dates about the beginning of the fourth century B.C., all is peace and harmony and clasped hands. The Delphic priesthood were past masters in the art of glossing over awkward passages in the history of theology. Apollo had to fight with the ancient mantic serpent of Gaia and slay it before he could take possession, and we may be very sure that at one time or another there was a struggle between the followers of Apollo and the followers of Dionysos. Over this past which was not for edification a decent veil was drawn.

A religion which conquered Delphi practically conquered the whole Greek world. It was probably at Delphi, no less than at Athens, that the work of reforming, modifying, adapting the rude Thracian worship was effected, a process necessary to commend the new cult to the favour of civilized Greece. If then we can establish the historical actuality of the Thyiads at Delphi we need not hesitate to believe that they, or their counterparts, existed in the worship of Dionysos elsewhere.

Pausanias when he was at Panopeus was puzzled to know why Homer spoke of the'fair dancing grounds'of the place. The reason he says was explained to him by the women whom the Athenians call Thyiades. He adds, that there may be no mistake, 'these Thyiads are Attic women who go every other year with the Delphian women to Parnassos and there hold orgies in honour of Dionysos. On their way they stopped to dance at Panopeus, hence Homer's epithet.' Of course this college of sacred women, these Thyiades, were provided with an eponymous ancestress, Thyia. She is mythological. Pausanias says in discussing the origin of Delphi that 'some would have it that there was a man called Castalius, an aboriginal, who had a daughter Thyia, and that she was the first priestess of Dionysos and held orgies in honour of the god, and they say that afterwards all women who were mad in honour of Dionysos have been called Thyiades after her. If those who are mad in honour of Dionysos'are not substantially Maenads, it is hard to say what they are. It is fortunate that Pausanias saw and spoke to these women or else his statement that they raved upon the topmost peaks of Parnassos in honour of Dionysos and Apollo would have been explained away as mere mythology.

Plutarch was a priest in his own Chaeronea and intimately acquainted with the ritual of Delphi, and a great friend of his, Klea, was president of the Thyiades at Delphi. He mentions them more than once. In writing to Favorinus on 'the First Principle of Cold' he argues that cold has its own special and proper qualities, density, stability, rigidity, and gives as an instance the cold of a winter's night out on Parnassos. 'You have heard yourself at Delphi how the people who went up Parnassos to bring help to the Thyiades were overtaken by a violent gale with snow, and their coats were frozen as hard as wood, so that when they were stretched out they crumbled and fell to bits.' The crumbling coats sound apocryphal, but the Thyiades out in the cold are quite real. You do not face a mountain snow-storm to succour the mythological'spirits of the spring.'

It may have been from his friend Klea that Plutarch learnt the pleasant story of the Thyiades and the women of Phocis, which he records in his treatise on the 'Virtues of Women.' 'When the tyrants of Phocis had taken Delphi and undertook against them what was known as the Sacred War, the women who attended Dionysos whom they call Thyiades being distraught wandered out of their way and came without knowing it to Amphissa. And being very weary and not yet having come to their right mind they flung themselves down in the agora and fell asleep anyhow where they lay. And the women of Amphissa were afraid lest, as their city had made an alliance with the Phocians and the place was full of the soldiery of the tyrants, the Thyiades might suffer some harm. And they left their houses and ran to the agora and made a ring in silence round them and stood there without disturbing them as they slept, and when they woke up they severally tended them and brought them food and finally got leave from their husbands to set them on their way in safety as far as the mountains.' These Thyiades are the historical counterparts of the Maenads of countless vases and bas-reliefs, the same mad revelry, the same utter exhaustion and prostrate sleep. They are the same too as the Bacchant Women of Euripides on the slopes of Cithaeron:

'There, beneath the trees

Sleeping they lay, like wild things flung at ease

In the forest, one half sinking on a bed

Of deep pine greenery, one with careless head

Amid the fallen oak-leaves.'

In the reverence shown by the women of Amphissa we see that though the Thyiades were real women they were something more than real. This brings us to another of the cultus titles enumerated by Timotheos, 'Phoibad.' Phoibas is the female correlative of Phoebus, a title we are apt to associate exclusively with Apollo. Apollo, Liddell and Scott say, was called Phoebus because of the purity and radiant beauty of youth. The epithet has more to do with purity than with radiant beauty; if with beauty at all it is'the beauty of holiness.' Plutarch in discussing this title of Apollo makes the following interesting statement 2: 'The ancients, it seems to me, called everything that was pure and sanctified phoebic as the Thessalians still, I believe, say of their priests when they are living in seclusion apart on certain prescribed days that they are living phoebically.' The meaning of - this passage, which is practically untranslateable, is clear. The v root of the word Phoebus meant'in a condition of ceremonial purity, holy in a ritual sense,'and as such specially inspired by and under the protection of the god, under a taboo. Apollo probably took over his title of Phoebus from the old order of women divinities to whom he succeeded. Third in order of succession after Gaia and Themis:

'Another Titaness, daughter of Earth,

Phoebe, possessed it, and for birthday gift

To Phoebus gave it, and he took her name.'

Apollo, we may be sure, did not get his birthday gift without substantial concessions. He took the name of the ancient Phoebe, daughter of earth, nay more he was forced, woman-hater as he always was, to utter his oracles through the mouth of a raving worn an -priestess, a Phoibas. Herodotus in the passage already quoted justly observed that in the remote land of the Bessi as at Delphi oracular utterance was by the mouth of a priestess. Kassandra was another of these women-prophetesses of Gaia. She prophesied at the altar-omphalos of Thymbrae, a shrine Apollo took over as he took Delphi. Her frenzy against , Apollo is more than the bitterness of maiden betrayed; it is the wrath of the prophetess of the old order discredited, despoiled by the new; she breaks her wand and rends her fillets and cries:

'Lo now the seer the seeress hath undone.'

The priestess at Delphi, though in intent a Phoibas, was called the Pythia, but the official name of the priestess Kassandra was, we know, Phoibas:

'The Phoibas whom the Phrygians call Kassandra,'

and the title, 'she who is ceremonially pure' lends a bitter irony to Hecuba's words of shame.

The word Phoibades is never, so far as I know, actually applied to definite Bacchantes, though I believe its use at Delphi to be due to Dionysiac influence, but another epithet Potniades points the same way. In the Bacchae, when the messenger returns from Cithaeron, he says to Pentheus:

'I have seen the wild white women there, king,

Whose fleet limbs darted arrow-like but now

From Thebes away, and come to tell thee how

They work strange deeds.

I The'wild white women'are in a hieratic state of holy madness, hence their miraculous magnetic powers. Photius has a curious note on the verb with which'Potniades'is connected. He says its normal use was to express a state in which a woman 'suffered something and entreated a goddess'and'if any one used the word of a man he was inaccurate.' By 'suffering something' he can only mean that she was possessed by the goddess, and he may have the Maenads and kindred worshippers in his mind. Madness could be caused by the Mother of the gods or by Dionysos, in fact by any orgiastic divinity.

It may possibly be objected that Maenads are not the same as either Thyiades or Phoibades. My point is that they are. The substantial basis of the conception is the actual women-worshippers of the god; out of these were later created his mythical attendants. Such is the natural order of mythological genesis. Diodorus like most modern mythologists inverts this natural sequence, and his inversion is instructive. In describing the triumphal return of Dionysos from India he says: 'And the Boeotians and the other Greeks and the Thracians in memory of the Indian expedition instituted the biennial sacrifices to Dionysos and they hold that at these intervals the god makes his epiphanies to mortals. Hence in many towns of Greece every alternate year Bacchanalian assemblies of women come together and it is customary for maidens to carry the thyrsos and to revel together to the honour and glory of the god, and the married women worship the god in organized bands and they revel, and in every way celebrate the presence of Dionysos in imitation of the Maenads who from of old, it was said, constantly attended the god.' Diodorus is an excellent instance of mistaken mythologizing. Mythology invents a reason for a fact, does not base a fact on a fancy.

It is not denied for a moment that the Maenads became mythical. When Sophocles sings:

'Footless, sacred, shadowy thicket, where a myriad berries grow.

Where no heat of the sun may enter, neither wind of the winter blow,

Where the Reveller Dionysos with his nursing nymphs will go,'

we are not in this world, and his nursing nymphs are 'goddesses'; but they are goddesses fashioned here as always in the image of man who made them.

The difficulty and the discrepancy of opinion as to the reality of the Maenads are due mainly to a misunderstanding about words. Maenad is to us a proper name, a fixed and crystallized personality; so is Thyiad, but in the beginning it was not so. Maenad is the Mad One, Thyiad the Rushing Distraught One or something of that kind, anyhow an adjectival epithet. Mad One, Distraught One, Pure One are simply ways of describing a woman under the influence of a god, of Dionysos. Thyiad and Phoibad obtained as cultus names, Maenad tended to go over to mythology. Perhaps naturally so; when a people becomes highly civilized madness is apt not to seem, save to poets and philosophers, the divine thing it really is, so they tend to drop the mad epithet and the colourless Thyiad becomes more and more a proper name.

Still Maenad, as a name of actual priestly women, was not wholly lost. An inscription of the date of Hadrian, found in Magnesia and now in the Tschinli Kiosk at Constantinople, gives curious evidence. This inscription recounts a little miracle-story. A plane tree was shattered by a storm, inside it was found an image of Dionysos. Seers were promptly sent to Delphi to ask what was to be done. The answer was, as might be expected, the Magnesians had neglected to build'fair wrought temples'to Dionysos; they must repair their fault. To do this properly they must send to Thebes and thence obtain three Maenads of the family of Kadmean Ino. These would give to the Magnesians orgies and right customs. They went to Thebes and brought back three'Maenads'whose names are given, Kosko, Baubo and Thettale; and they came and founded three thiasoi or sacred guilds in three parts of the city. The inscription is of course late; Baubo and Kosko are probably Orphic, but the main issue is clear: in the time of Hadrian at least three actual women of a particular family were called 'Maenads.'

We are so possessed by a set of conceptions based on Periclean Athens, by ideas of law and order and reason and limit, that we are apt to dismiss as'mythological'whatever does not fit into our stereotyped picture. The husbands and brothers of the women of historical days would not, we are told, have allowed their women to rave upon the mountains; it is unthinkable taken in conjunction with the strict oriental seclusion of the Periclean woman. That any woman might at any moment assume the liberty of a Maenad is certainly unlikely, but much is borne even by husbands and brothers when sanctioned by religious tradition. The men even of Macedonia, where manners were doubtless ruder, did not like the practice of Bacchic orgies. Bacchus came emphatically not to bring peace. Plutarch conjectures that these Bacchic orgies had much to do with the strained relations between the father and mother of Alexander the Great. A snake had been seen lying by the side of Olympias and Philip feared she was practising enchantments, or worse, that the snake was the vehicle of a god. Another and probably the right explanation of the presence of the snake was, as Plutarch tells us, that'all the women of that country had been from ancient days under the dominion of Orphic rites and Dionysiac orgies, and that they were called Klodones and Mimallones because in many respects they imitated the Edonian and Thracian women round about Haemus, from whom the Greek word Bprfcriceveiv seems to come, a word which is applied to excessive and overdone ceremonials. Now Olympias was more zealous than all the rest and carried out these rites of possession and ecstasy in very barbarous fashion and introduced huge tame serpents into the Bacchic assemblies, and these kept creeping out of the ivy and the mystic likna and twining themselves round the thyrsoi of the women and their garlands, and frightening the men out of their senses'

However much the Macedonian men

disliked these orgies, they were clearly too frightened to put a

stop to them.

However much the Macedonian men

disliked these orgies, they were clearly too frightened to put a

stop to them.

The women were possessed, magical, and dangerous to handle. Scenes such as those described by Plutarch as actually taking place in Macedonia are abundantly figured on vases.

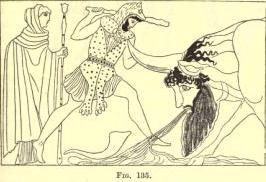

The beautiful raging Maenad in fig. 125 from the centre of a cylix with white ground at Munich is a fine example. She wears the typical Maenad garb, the fawn-skin over her regular drapery; she carries the thyrsos, she carries in fact the whole gear of Dionysos.

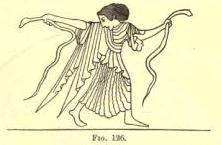

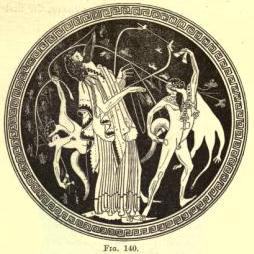

When Pentheus would counterfeit a

Bacchant he is attired just so; he wears the long trailing chiton

and over it the dappled fawn-skin, his hair flows loose, in his

hand is the thyrsos. For snood in her hair the Maenad has twined

a great snake. Another Maenad is shown in fig. 126. She is

characterized only by the two snakes she holds in her hand. But

for her long full drapery she might be an Erinys.

When Pentheus would counterfeit a

Bacchant he is attired just so; he wears the long trailing chiton

and over it the dappled fawn-skin, his hair flows loose, in his

hand is the thyrsos. For snood in her hair the Maenad has twined

a great snake. Another Maenad is shown in fig. 126. She is

characterized only by the two snakes she holds in her hand. But

for her long full drapery she might be an Erinys.

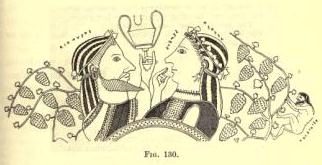

The snakes emerging from the sacred

cistae are illustrated by the class of coins known as

cistophoroi, a specimen of which is reproduced in fig. 127. These

coins, of which the type is uniform, originated, according to Dr

Imhoof, in Ephesus a little before B.C. 200, and spread through

air the dominions of Attalos the First. They illustrate a phase

of Dionysos worship in Asia Minor closely akin to that of

Macedonia.

The snakes emerging from the sacred

cistae are illustrated by the class of coins known as

cistophoroi, a specimen of which is reproduced in fig. 127. These

coins, of which the type is uniform, originated, according to Dr

Imhoof, in Ephesus a little before B.C. 200, and spread through

air the dominions of Attalos the First. They illustrate a phase

of Dionysos worship in Asia Minor closely akin to that of

Macedonia.

Macedonia is not Athens, but the reforms of Epimenides allow us to divine that Athenian brothers and husbands also had their difficulties. Plutarch again is our informant. Athens was beset by superstitious fears and strange appearances. They sent to Crete for Epimenides, a man beloved of the gods and skilled in the technicalities of religion, especially as regards enthusiastic and mystic rites. He and Solon made friends and the gist of his religious reforms was this:'he simplified their religious rites, and made the ceremonies of mourning milder, introducing certain forms of sacrifice into their funeral solemnities and abolishing the cruel and barbarous elements to which the women were addicted. But most important of all, by lustrations and expiations and the foundings of worships he hallowed and consecrated the city and made it subserve justice and be more inclined to unity. The passage is certainly not as explicit as could be wished, but the words used Karopyidaas and Kado(7iwaa; and the fact that Epimenides was an expert in ecstatic rites, that they gave him the name of the new Koures, the special attention paid to the rites of women, though they are mentioned in relation to funerals, make it fairly clear that some of the barbarous excesses were connected with Bacchic orgies. This becomes more probable when we remember that many of Solon's own enactments were directed against the excesses of women.' He regulated Plutarch tells us,'the outgoings of women, their funeral lamentations and their festivals, forbidding by law all disorder and excess/ Among these dreary regulations comes the characteristically modern touch that they are not to go out at night'except in a carriage and with a light before them. It was the going out at night that Pentheus could not bear. When he would know what were the rites of Dionysos he asks the god:

P. How is this worship held, by night or day?

D. Most oft by night,'tis a majestic thing

The Darkness.

P. Ha, with women worshipping?

Tis craft and rottenness.

Dionysos Liknites

The Maenads then are the frenzied sanctified women who are devoted to the worship of Dionysos. But they are something more; they tend the god as well as suffer his inspiration. When first we catch sight of them in Homer they are his 'nurses'. One of the lost plays of Aeschylus bore the title 'Rearer of Dionysos,' and Sophocles, here as so often inspired by Homer, makes his chorus sing:

There the reveller Dionysos with his nursing nymphs doth go.'

In Homer and Aeschylus and Sophocles, though Dionysos has his goddess nurses, he is himself no nursling. A child no longer, he revels with them as coevals. Mythology has half forgotten the ritual from which it sprang. Fortunately Plutarch has left us an account, inadequate but still significant, of the actual ritual of the Thyiades, and from it we learn that they worshipped and tended no full-grown god, but a baby in his cradle.