|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER IX.

OEPHEUS.

Orpheus As Magical Musician | The Death of Orpheus | Orpheus and Helios | Hero-shrine of Orpheus | Orpheus At Athens | Cardinal Doctrine of Orphism | Immortality through Divinity

MYTHOLOGY has left us no tangle more intricate and assuredly no problem half so interesting as the relation between the ritual and mythology of Orpheus and Dionysos.

By the time of Herodotus the followers of Orpheus and of Bacchus are regarded as substantially identical. In commenting on the taboo among the Egyptians against being buried in woollen garments he says: 'In this respect they agree with the rites which are called Bacchic and Orphic but are really Egyptian and Pythagorean.'The identification is of course a rough and ready one, an identification of race on the precarious basis of a similarity of rites, but one thing is clear to the mind of Herodotus Orphic and Bacchic and Egyptian rites are either identical or closely analogous. The analogy between Orpheus and Bacchus passed by the time of Euripides into current language. Theseus when he would taunt Hippolytus with his pseudo-asceticism says:

'Go revel thy Bacchic rites

With Orpheus for thy Lord,'

and Apollodorus in his systematic account of the Muses states that Orpheus'invented the mysteries of Dionysos.'The severance of the two figures by modern mythologists has often led to the misconception of both. The full significance, the higher spiritual developments of the religion of Dionysos are only understood through the doctrine of Orpheus, and the doctrine of Orpheus apart from the religion of Dionysos is a dead letter.

And yet, clearly linked though they are, the most superficial survey reveals differences so striking as to amount to a spiritual antagonism. Orpheus reflects Dionysos, yet at almost every point seems to contradict him. The sober gentle musician, the precise almost pedantic theologist, is no mere echo, no reincarnation of the maddened, maddening wine-god. Diodorus expresses a truth that must have struck every thinker among the Greeks, that this real and close resemblance veiled an inner, intimate discrepancy. He says, in telling the story of Lycurgus,'Charops, grandfather of Orpheus, gave help to the god, and Dionysos in gratitude instructed him in the orgies of his rites; Charops handed them down to his son Oiagros, and Oiagros to his son Orpheus.' Then follow the significant words:'Orpheus, being a man gifted by nature and highly trained above all others, made many modifications in the orgiastic rites: hence they call the rites that took their rise from Dionysos, Orphic.'Diodorus seems to have put his finger on the secret of Orpheus. He comes later than Dionysos, he is a man not a god, and his work is to modify the rites of the god he worshipped.

It is necessary at the outset to emphasize the humanity of Orpheus. About his legend has gathered much that is miraculous and a theory has been started and supported with much learning and ability, a theory which sees in Orpheus an underworld god, the chthonic counterpart of Dionysos, and that derives his name from chthonic darkness. This is to my mind to misconceive the whole relation between the two.

Orpheus As Magical Musician

Like the god he served, Orpheus is at one part of his career a Thracian, unlike him a magical musician. Dionysos, as has been seen, played upon the lyre, but music was never of his essence.

In the matter of Thracian music we are happily on firm ground. The magical musician, whose figure to the modern mind has almost effaced the theologist, comes as would be expected from the home of music, the North. Conon in his life of Orpheus says expressly, 'the stock of the Thracians and Macedonians is music-loving.' Strabo too is explicit on this point. In the passage already quoted, on the strange musical instruments used in the orgies of Dionysos, he says:'Similar to these (i.e. the rites of Dionysos) are the Kotyttia and Bendideia practised among the Thracians, and with them also Orphic rites had their beginning. A little further he goes on to say that the Thracian origin of the worship of the Muses is clear from the places sacred to their cult. 'For Pieria and Olympus and Pimplea and Leibethra were of old Thracian mountains and districts, but are now held by the Macedonians, and the Thracians who colonized Boeotia consecrated Helicon to the Muses and also the cave of the Nymphs called Leibethriades. And those who practised ancient music are said to have been Thracians, Orpheus and Musaeus and Thamyris, and the name Eumolpus comes from Thrace.'

The statement of Strabo is noticeable. As Diodorus places Orpheus two generations later than Dionysos, so the cult of the Muses with which Orpheus is associated seems chiefly to prevail in Lesbos and among the Cicones of Lower Thrace and Macedonia. We do not hear of Orpheus among the remote inland Bessi. This may point to a somewhat later date of development when the Thracians were moving southwards. That there were primitive and barbarous tribes living far north who practised music we know again from Strabo. He tells of an Illyrian tribe, the Dardanii, who were wholly savage and lived in caves they dug under dung-heaps, but all the same they were very musical and played a great deal on pipes and stringed instruments. The practice of music alone does not even now-a-days necessarily mark a high level of culture, and the magic of Orpheus was, as will later be seen, much more than the making of sweet sounds.

Orpheus, unlike Dionysos, remained consistently a Northerner. We have no universal spread of his name, no fabulous birth stories everywhere, no mystic Nysa; he does not take whole nations by storm, he is always known to be an immigrant and is always of the few. At Thebes we hear of magical singers Zethus and Amphion, but not of Orpheus. In Asia he seems never to have prevailed; the orgies of Dionysos and the Mother remained in Asia in their primitive Thracian savagery. It is in Athens that he mainly re-emerges.

To the modern mind the music of Orpheus has become mainly fabulous, a magic constraint over the wild things of nature.

'Orpheus with his lute made trees

And the mountain tops that freeze

Bow themselves when he did sing.'

This notion of the fabulous music was already current in antiquity. The Maenads in the Bacchae call to their Lord to come from Parnassos,

'Or where stern Olympus stands

In the elm woods or the oaken,

There where Orpheus harped of old,

And the trees awoke and knew him,

And the wild things gathered to him,

As he sang among the broken

Glens his music manifold,'

and again in the lovely song of the Alcestis, the chorus sing to Apollo who is but another Orpheus:

'And the spotted lynxes for joy of thy song

Were as sheep in the fold, and a tawny throng

Of lions trooped down from Othrys'lawn,

And her light foot lifting, a dappled fawn

Left the shade of the high-tressed pine,

And danced for joy to that lyre of thine.'

In Pompeian wall-paintings and Graeco-Roman sarcophagi is as magical musician, with power over all wild untamed things in nature, that Orpheus appears. This conception naturally passed into Christian art and it is interesting to watch the magical musician transformed gradually into the Good Shepherd. The bad wild beasts, the lions and lynxes, are weeded out one by one, and we are left, as in the wonderful Ravenna mosaic, with only a congregation of mild patient sheep.

It is the more interesting to find that on black and red-figured vase-paintings, spite of this literary tradition, the power of the magical musician is quite differently conceived. Orpheus does not appear at all on black-figured vases again a note of his late coming and on red-figured vases never with the attendant wild beasts.

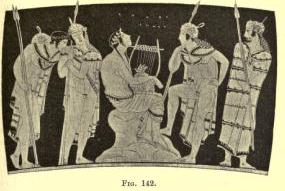

On a vase found at Gela and now in

the Berlin Museum, reproduced in fig. 142, we have Orpheus as

musician. He wears Greek dress and sits playing on his lyre with

up-turned head, utterly aloof, absorbed. And round him are not

wild beasts but wild men, Thracians. They wear uniformly the

characteristic Thracian dress, the fox-skin cap and the long

embroidered cloak, of both of which Herodotus makes mention as

characteristic. The Thracians who joined the Persian expedition,

he says, 'wore fox-skins on their heads and were clothed with

various-coloured cloaks.' These wild Thracians in the

vase-painting are all intent on the music; the one to the right

looks suspicious of this new magic, the one immediately facing

Orpheus is determined to enquire into it, the one just behind has

gone under completely; his eyes are shut, his head falling, he is

mesmerized, drunken but not with wine.

On a vase found at Gela and now in

the Berlin Museum, reproduced in fig. 142, we have Orpheus as

musician. He wears Greek dress and sits playing on his lyre with

up-turned head, utterly aloof, absorbed. And round him are not

wild beasts but wild men, Thracians. They wear uniformly the

characteristic Thracian dress, the fox-skin cap and the long

embroidered cloak, of both of which Herodotus makes mention as

characteristic. The Thracians who joined the Persian expedition,

he says, 'wore fox-skins on their heads and were clothed with

various-coloured cloaks.' These wild Thracians in the

vase-painting are all intent on the music; the one to the right

looks suspicious of this new magic, the one immediately facing

Orpheus is determined to enquire into it, the one just behind has

gone under completely; his eyes are shut, his head falling, he is

mesmerized, drunken but not with wine.

This beautiful picture brings to our minds very forcibly one note of Orpheus, as contrasted with Dionysos, his extraordinary quiet. Orpheus never plays the flute 'that rouses to madness' nor clangs the deafening cymbals; he plays always on the quiet lyre, and he is never disturbed or distraught by his own music. He is the very mirror of that'orderliness and grave earnestness' which, as we have seen, Plutarch took to be the note of Apollo. Small wonder that Apollo was imaged as Orpheus.

Orpheus, before the dawn of history, had made his home in Thrace. His music is all of the North, but after all, though mythology always emphasizes this music, it was not the whole secret of his influence. He was more priest than musician. Moreover, though Orpheus has certain Apolline touches, the two figures are not really the least like. About Apollo there is no atmosphere of mysticism, nothing mysterious and ineffable; he is all sweet reasonableness and lucidity. Orpheus came to Thrace and thence to Thessaly, but he came, I believe, from the South. It will later be seen that his religion in its most primitive form is best studied in Crete. In Crete and perhaps there only is found that strange blend of Egyptian and primitive Pelasgian which found its expression in Orphic rites. Diodorus says Orpheus went to Egypt to learn his ritual and theology, but in reality there was no need to leave his native island. From Crete by the old island route he passed northwards, leaving his mystic rites as he passed at Paros, at Samos, at Samothrace, at Lesbos. At Maroneia among the Cicones he met the vine-god, among the Thracians he learnt his music. All this is by anticipation. That Crete was the home of Orphism will best be seen after examination of the mysteries of Orpheus. For the present we must be content to examine his mythology.

The contrast between Orpheus and Dionysos is yet more vividly emphasized in the vase-painting next to be considered (fig. 143), from a red-figured hydria of rather late style. Again Orpheus is the central figure, and again a Thracian in his long embroidered cloak and fox-skin cap is listening awe-struck. It is noticeable that in this and all red-figured vases of the fine period Orpheus is dressed as a Greek; he has been wholly assimilated, nothing in his dress marks him from Apollo. It is not till a very late date, and chiefly in Lower Italy, that the vase-painter shows himself an archaeologist and dresses Orpheus as a Thracian priest. Not only a Thracian but a Satyr looks and listens entranced.

But this time Orpheus will not work his magic will. He may tame the actual Thracian, he may tame the primitive population of Thrace mythologically conceived of as Satyrs, but the real worshipper of Dionysos is untameable as yet. Up from behind in hot haste comes a Maenad armed with a great club, and we foresee the pitiful end.

The Death of Orpheus

The story of the slaying of Orpheus by the Thracian women, the Maenads, the Bassarids, is of cardinal importance. It was the subject of a lost play by Aeschylus, but vases of the severe red-figured style remain our earliest extant source. Manifold reasons, to suit the taste of various ages, were of course invented to account for the myth. Some said Orpheus was slain by Zeus because Prometheus-like he revealed mysteries to man. When love came into fashion he suffers for his supposed sin against the Love-God. Plato made him be done to death by the Maenads, because, instead of dying for love of Eurydice, he went down alive into Hades. But serious tradition always connected his death somehow with the cult of Dionysos. According to one account he died the death of Dionysos himself. Proklos in his commentary on Plato says: 'Orpheus, because he was the leader in the rites of Dionysos, is said to have suffered the like fate to his god.' It will later be shown in discussing Orphic mysteries that an important feature in Dionysiac religion was the rending and death of the god, and no doubt to the faithful it seemed matter of edification that Orpheus, the priest of his mysteries, should suffer the like passion.

But in the myth of the death by the hands of the Maenads there is another element, possibly with some historical kernel, the element of hostility between the two cults, the intimate and bitter hostility of things near akin. The Maenads tear Orpheus to pieces, not because he is an incarnation of their god, but because he despises them and they hate him. This seems to have been the form of the legend followed by Aeschylus. It is recorded for us by Eratosthenes. 'He (Orpheus) did not honour Dionysos but accounted Helios the greatest of the gods, whom also he called Apollo. And rising up early in the morning he climbed the mountain called Pangaion and waited for the rising of the sun that he might first catch sight of it. Therefore Dionysos was enraged and sent against him his Bassarids, as Aeschylus the poet says. And they tore him to pieces and cast his limbs asunder. But the Muses gathered them together and buried them in the place called Leibethra.' Orpheus was a reformer, a protestant; there is always about him a touch of the reformer's priggishness; it is impossible not to sympathize a little with the determined looking Maenad who is coming up behind to put a stop to all this sun-watching and lyre-playing.

The devotion of Orpheus to Helios is noted also in the hypothesis to the Orphic Lithika. Orpheus was on nis way up a mountain to perform an annual sacrifice in company with some friends when he met Theiodamas. He tells Theiodamas the origin of the custom. When Orpheus was a child he was nearly killed by a snake and he took refuge in a neighbouring sanctuary of Helios. The father of Orpheus instituted the sacrifice and when his father left the country Orpheus kept it up. Theiodamas waits till the ceremony is over, and then follows the discourse on precious stones.

Orpheus and Helios

That there was a Thracian cult of the Sun-god later fused with that of Apollo is certain. Sophocles in the Tereus made some one say:

'0 Helios, name

To Thracian horsemen dear, eldest flame!'

Helios was a favourite of monotheism, as we learn from another fragment of Sophocles:

'Helios, have pity on me,

Thou whom the wise men call the sire of gods

And father of all things.'

The 'wise men' here as in many other passages may actually be Orphic teachers, anyhow they are specialists in theology. Helios, as all-father, has the air of late speculation, but such speculations are often only the revival in another and modified form of a primitive faith. By the time of Homer, Helios had sunk to a mere impersonation of natural fact, but he may originally have been a potent sky god akin to Keraunios and to Ouranos, who was himself effaced by Zeus. Orpheus was, as will later be seen, a teacher of monotheism, and it was quite in his manner to attempt the revival of an ancient and possibly purer faith.

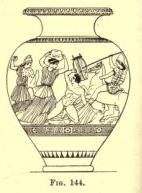

Be this as it may, it is quite

certain that ancient tradition made him the foe of Dionysos and

the victim of the god's worshippers. His death at their hands is

depicted on numerous vase-paintings of which a typical instance

is given in fig. 144. The design is from a red-figured stamnos in

the Museo Gregoriano of the Vatican. The scheme is usually much

the same; we have the onset of the Thracian women bearing clubs

or double axes or great rocks for weapons. Usually they are on

foot, but on the Vatican stamnos one Maenad appears mounted,

Amazon fashion. Before this fierce onset the beautiful musician

falls helpless, his only weapon of defence the innocent lyre. On

a cylix with white ground about the date of Euphronios, the

Thracian Maenad who slays Orpheus is tattooed; on the upper part

of her right arm is clearly marked a little stag. Popular

aetiology connected this tattooing with the death of Orpheus. The

husbands of the wicked women tattooed them as a punishment for

their crime, and all husbands continued the practice down to the

time of Plutarch. Plutarch says he 'cannot praise them, 'as long

protracted punishment is the prerogative of the Deity.' Prof.

Ridgeway has shown that the practice of tattooing was in use

among the primitive Pelasgian population but never adopted by the

Achaeans. The Maenads triumphed for a time.

Be this as it may, it is quite

certain that ancient tradition made him the foe of Dionysos and

the victim of the god's worshippers. His death at their hands is

depicted on numerous vase-paintings of which a typical instance

is given in fig. 144. The design is from a red-figured stamnos in

the Museo Gregoriano of the Vatican. The scheme is usually much

the same; we have the onset of the Thracian women bearing clubs

or double axes or great rocks for weapons. Usually they are on

foot, but on the Vatican stamnos one Maenad appears mounted,

Amazon fashion. Before this fierce onset the beautiful musician

falls helpless, his only weapon of defence the innocent lyre. On

a cylix with white ground about the date of Euphronios, the

Thracian Maenad who slays Orpheus is tattooed; on the upper part

of her right arm is clearly marked a little stag. Popular

aetiology connected this tattooing with the death of Orpheus. The

husbands of the wicked women tattooed them as a punishment for

their crime, and all husbands continued the practice down to the

time of Plutarch. Plutarch says he 'cannot praise them, 'as long

protracted punishment is the prerogative of the Deity.' Prof.

Ridgeway has shown that the practice of tattooing was in use

among the primitive Pelasgian population but never adopted by the

Achaeans. The Maenads triumphed for a time.

'What could the Muse herself that Orpheus bore,

The Muse herself for her enchanting son,

Whom universal nature did lament,

When by the rout that made the hideous roar

His gory visage down the stream was sent,

Down the swift Hebrus to the Lesbian shore?'

The dismal savage tale comes to a gentle close. The head of Orpheus, singing always, is found by the Muses, and buried in the sanctuary at Lesbos. Who are the Muses? Who but the Maenads repentant, clothed and in their right minds.

That Maenads and Muses, widely diverse though they seem to us, were not by classical writers sharply sundered is seen in the variant versions of the story of Lycurgus. Dionysos in Homer is attended by his nurses and these, as has already been shown, are Maenads, but, when we come to Sophocles, these same nurses, these'god-inspired women, are not Maenads, but Muses. The chorus in the Antigone sings of Lycurgus; how he

'Set his hand

To stay the god-inspired woman-band,

To quell his Women and his joyous fire,

And rouse the fluting Muses into ire.'

Nor is it poetry only that bears witness. In the introduction to the eighth book of his Symposiacs Plutarch is urging the importance of mingling improving conversation with the drinking of wine. 'It is a good custom,' he says, 'that our women have, who in the festival of the Agrionia seek for Dionysos as though he had run away, and then they give up seeking and say that he has taken refuge with the Muses and is lurking with them, and after some time when they have finished their feast they ask each other riddles and conundrums. And this mystery teaches us'In some secret Bacchic ceremonial extant in the days of Plutarch and carried on by women only, Dionysos was supposed to be in the hands of his women attendants, but they were known as Muses not as Maenads. The shift of Maenad to Muse is like the change of Bacchic rites to Orphic; it is the informing of savage rites with the spirit of music, order and peace.

Hero-shrine of Orpheus

Tradition says that Orpheus was buried by the Muses, and fortunately of his burial-place we know some definite particulars. It is a general principle in mythology that the reputed death-place of a god or hero is of more significance than his birth-place, because, among a people like the Greeks, who practised hero-worship, it is about the death-place and the tomb that cultus is set up. The birth-place may have a mythical sanctity, but it is at the death-place that we can best study ritual practice.

Philostratos in the Heroicus says: 'After the outrage of the women the head of Orpheus reached Lesbos and dwelt in a cleft of the island and gave oracles in the hollow earth.' It is clear that we have here some form of Nekyomanteion, oracle of the dead. Of such there were many scattered all over Greece; in fact, as has already been seen, the tomb of almost any hero might become oracular. The oracular tomb of Orpheus became of wide repute. Inquirers, Philostratos tells us, came to it even from far-off Babylon. It was from the shrine of Orpheus in Lesbos that in old days there came to Cyrus the brief, famous utterance: 'Mine, O Cyrus, are thine'

Lucian adds an important statement. In telling the story of the head and the lyre he says:'The head they buried at the place where now they have a sanctuary of Bacchus. The lyre on the other hand was dedicated in a sanctuary of Apollo.'The statement carries conviction. It would have been so easy to bury head and lyre together. The truth probably was that the lyre was a later decorative addition to an old head-oracle story; the head was buried in the shrine of the god whose religion Orpheus reformed.

Antigonus in his 'History of Wonderful Things' records a lovely tradition. He quotes as his authority Myrtilos, who wrote a treatise on Lesbian matters. Myrtilos said that, according to the local tradition, the tomb of the head of Orpheus was shown at Antissaia, and that the nightingales sang there more sweetly than elsewhere. In those wonder-loving days a bird had but to perch upon a tomb and her song became a miracle.

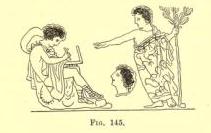

The oracle shrine of Orpheus is

depicted for us on a somewhat late red-figured cylix of which the

obverse is reproduced in fig. 145. It is our earliest definite

source for his cult. The head of Orpheus is prophesying with

parted lips. We are reminded of the vase-painting in fig. 10,

where the head of Teiresias emerges bodily from the sacrificial

trench near which Odysseus is seated. A youth has come to consult

the oracle and holds in his hands a tablet and style. Whether he

is putting down his own question or the god's answer is

uncertain. We know from Plutarch that at the oracle shrine of

another hero, Mopsos, questions were sometimes sent in on sealed

tablets. In the case cited by Plutarch a test question was set

and the oracle proved equal to the occasion. The vase-painting

calls to mind the lines in the Alcestis of Euripides where the

chorus sings:

The oracle shrine of Orpheus is

depicted for us on a somewhat late red-figured cylix of which the

obverse is reproduced in fig. 145. It is our earliest definite

source for his cult. The head of Orpheus is prophesying with

parted lips. We are reminded of the vase-painting in fig. 10,

where the head of Teiresias emerges bodily from the sacrificial

trench near which Odysseus is seated. A youth has come to consult

the oracle and holds in his hands a tablet and style. Whether he

is putting down his own question or the god's answer is

uncertain. We know from Plutarch that at the oracle shrine of

another hero, Mopsos, questions were sometimes sent in on sealed

tablets. In the case cited by Plutarch a test question was set

and the oracle proved equal to the occasion. The vase-painting

calls to mind the lines in the Alcestis of Euripides where the

chorus sings:

'Though to high heaven I fly,

Borne on the Muses'wing,

Thinking great thoughts, yet do I find no thing

Stronger than stern Necessity.

No not the spell

On Thracian tablets legible

That from the voice of Orpheus fell,

Nor those that Phoebus to Asklepios gave

That he might weary woe-worn mortals save.'

Orpheus on the vase-painting is a voice and nothing more. As to the tablets, if we may trust the scholiast on the passage, tablets accredited to Orpheus actually existed. He quotes Herakleitos the philosopher as stating that Orpheus' set in order the religion of Dionysos in Thrace on Mount Haemus, where they say there are certain writings of his on tablets. There is no reason to doubt the tradition, and it serves to emphasize the fact that Orpheus was an actual person, living, teaching, writing, writing perhaps in those old 'Pelasgian' characters which Linos used long before the coming of Phoenician letters, characters which it may be are those still undeciphered which have come to light in Crete.

Above the head of Orpheus in the vase-painting (fig. 145) stands Apollo. In his left hand he holds his prophetic staff of laurel, his right is outstretched, but whether to command or forbid is hard to say. A curious account of the oracle on Lesbos given by Philostratos in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana informs us that the relations of Apollo and Orpheus were not entirely peaceable. Apollonius, says Philostratos, landed at Lesbos and visited the adyton of Orpheus. They say that in this place of old Orpheus was wont to take pleasure in prophecy until Apollo took the oversight himself. For inasmuch as men no longer resorted to Gryneion for oracles nor to Klaros nor to the place of the tripod of Apollo, but the head of Orpheus, recently come from Thrace, alone gave responses, the god came and stood over him as he uttered oracles and said: 'Cease from the things that are mine, for long enough have I borne with thee and thy singing.'Apollo will brook no rivalry even of his most faithful worshipper. The quaint story is evidence of the intolerance of a dominant and missionary cult.

Most circumstantial of all accounts of Orpheus is that given by Conon. No one would of course accept as evidence en bloc the statements of Conon, concerned as he mainly is to compile a complete and interesting story. Certain of his statements however have an inherent probability which makes them of considerable value. He devotes to Orpheus the whole of one of his narrations. He tells all the orthodox details, how Orpheus won the hearts of Thracians and Macedonians by his music, how he charmed rocks and trees and wild beasts and even the heart of Kore, queen of the underworld. Then he proceeds to the story of the death. Orpheus refused to reveal his mysteries to women, whom since the loss of his own wife he had hated en masse. The men of Thrace and Macedonia were wont to assemble in arms on certain fixed days, in a building at Leibethra of large size and well arranged for the purpose of the celebration of rites. When they went in to celebrate their orgiastic rites they laid down their arms before the entrance gate. The women watched their opportunity, seized the arms, slew the men and tore Orpheus to pieces, throwing his limbs into the sea. There was the usual pestilence in consequence and the oracular order that the head of Orpheus should be buried. After some search the head was found by a fisherman at the mouth of the river Meles.' It was still singing nor had it suffered any change from the sea, nor any other of the outrages that the Keres which beset mortals inflict on the dead, but it was still blooming and even then after the long lapse of time it was bleeding with fresh blood.'Other stories of bleeding miraculous heads occur in antiquity. Aelian records several and Phlegon in his'Wonders'tells of the miracle that happened at the battle against Antiochus in 191 A.D. A bleeding head gave an oracle in elegiac verse and very wisely ordained that the spectators were not to touch it but only to listen.

The details supplied by Conon are of course aetiological, but we seem to discern behind them some possible basis of historical fact, some outrage of the wild women of Thrace against a real immigrant prophet in whose reforms they saw contempt of their rites. The blood of some real martyr may have been the seed of the new Orphic church. How this came to be Conon at the end of his narrative explains:'When the miraculous head, singing and bleeding, was found, they took it and buried it beneath a great monument and fenced it in with a sacred precinct, a precinct that no woman might ever enter.'The significant statement is added that the tomb with its precinct was at first a heroon, but later it obtained as a hieron and the proof was that it was honoured with burnt sacrifices and all the other meeds of the gods.

Conon has undoubtedly put his finger on the truth. Orpheus was a real man, a mighty singer, a prophet and a teacher, bringing with him a new religion, seeking to reform an old one. He was martyred and after his death his tomb became a mantic shrine. So long as it was merely a hero shrine the offerings were those proper to the dead, but an effort was made by the faithful to raise him to the rank of an upperworld Olympian. Locally burnt sacrifices, the meed of the Olympians of the upper air, were actually no doubt offered, but the cult of Orpheus as a god did not obtain. Translation to the Upper House of the Olympians was not always wholly promotion. What you gain as a personage you are apt to lose as a personality. Orpheus sacrificed divinity to retain his beautiful humanity. He is somewhere on the same plane with Herakles and Asklepios, too human ever to be quite divine. But the escape was a narrow one. Probably if a greater than he, Apollo, had not 'taken the oversight,' the sequel would have been otherwise.

Conon writing in the time of Augustus believed Orpheus to have been a real man. So did Strabo. In describing the Thermaean gulf he says that the city of Dium is not on the coast but about seven stadia distant and'near the city of Dium is a village called Pimpleia where Orpheus lived.... Orpheus was of the tribe of the Cicones and was a man of magical power both as regards music and divination. He went about practising orgiastic rites and later, waxing self-confident, he obtained many followers and great influence. Some accepted him willingly, others, suspecting that he meditated violence and conspiracy, attacked and slew him.' He adds that 'in olden times prophets were wont to practise the art of music also.'

Still more completely human is the picture that Pausanias draws of the life and work of Orpheus. In the monument to Orpheus that he saw on Mt. Helicon the spell-bound beasts are listening to the music, and by the musician's side is the figure of Telete, 'Rite of Initiation.' Pausanias comments as follows: 'In my opinion Orpheus was a man who surpassed his predecessors in the beauty of his poems and attained to great power, because he was believed to have discovered rites of the gods and purifications for unholy deeds and remedies for diseases and means of averting divine wrath.'And again, at the close of his account of the various miraculous legends that had gathered about Orpheus he says: 'Whoever has concerned himself with poetry knows that all the hymns of Orpheus are short and that the number of them all is not great. The Lycomids know them and chant them over their rites. In beauty they may rank as second to the hymns of Homer, but they have attained to even higher divine favour.'

Pausanias puts the relation between Homer and Orpheus in much the same fashion as Aristophanes, who makes Aeschylus recount the service of poets to the state:

'It was Orpheus revealed to us holy rites, our hands from bloodshed withholding;

Musaeos gave us our healing arts, oracular words unfolding;

And Hesiod showed us to till the earth and the seasons of fruits and ploughing;

But Homer the god-like taught good things, and this too had for his glory

That he sang of arms and battle array and deeds renowned in story.'

Homer sang of mortals, Orpheus of the gods; both are men, but of the two Orpheus is least fabulous. About both gather alien accretions, but the kernel remains human not divine.

Orpheus then halted half way on the ladder between earth and heaven, a ladder up which many mortals have gone and vanished into the remote unreality of complete godhead.

S. Augustine admirably hits the mark when he says: 'After the same interval of time there came the poets, who also, since they wrote poems about the gods, are called theologians, Orpheus, Musaeus, Linus. But these theologians were not worshipped as gods, though in some fashion the kingdom of the godless is wont to set Orpheus as head over the rites of the underworld.'

The line indeed between hero and underworld god was, as has already been abundantly seen, but a shifting shadow. It is useless however to urge that because Orpheus had a local shrine and a cult he was therefore a god in the current acceptation of the term. Theseus had a shrine, so had Diomede, so had each and every canonical hero; locally they were potent for good and evil, but we do not call them gods. Athenaeus marks the distinction. 'Apollo', he says,'the Greeks accounted the wisest and most musical of the gods, and Orpheus of the semi-gods.'

Once we are fairly awake to the fact that Orpheus was a real live man, not a faded god, we are struck by the human touches in his story, and most by a certain vividness of emotion, a reality and personality of like and dislike that attends him. He seems to have irritated and repelled some as much as he attracted others. Pausanias tells how of old prizes were offered for hymns in honour of a god. Chrysothemis of Crete and Philammon and Thamyris come and compete like ordinary mortals, but Orpheus 'thought such great things of his rites and his own personal character that he would not compete at all.'Always about him there is this aloof air, this remoteness, not only of the self-sufficing artist, who is and must be always alone, but of the scrupulous moralist and reformer; yet withal and through all he is human, a man, who Socrates-like draws men and repels them, not by persuading their reason, still less by enflaming their passions, but by sheer magic of his personality. It is this mesmeric charm that makes it hard even now-a-days to think soberly of Orpheus.

Orpheus At Athens

Orpheus, poet, seer, musician, theologist, was a man and a Thracian, and yet it is chiefly through his influence at Athens that we know him. The author of the Rhesos makes the Muse complain that it is Athene not Odysseus that is the cause of the tragedy that befell the Thracian prince. She thus appeals to the goddess:

'And yet we Muses, we his kinsmen hold

Thy land revered and there are wont to dwell,

And Orpheus, he own cousin to the dead,

Kevealed to thee his secret mysteries.'

The tragedian reflects the double fact the Thracian provenance, the naturalization in Athens.

Orpheus, we know, reorganized and reformed the rites of Bacchus. How much he was himself reorganized and reformed we shall never fully know. The work of editing and popularizing Orpheus at Athens was accredited to Onomacritos, he who made the indiscreet interpolation in the oracles of Musaeus and was banished for it by the son of Peisistratos. If Onomacritos interpolated oracles into the poems of Musaeus, why should he spare Orpheus? Tatian writes that 'Orpheus was contemporary with Herakles,' another note that he is heroic rather than divine, and adds:'They say that the poems that were circulated under the name of Orpheus were put together by Onomacritos the Athenian.' Clement goes further. He says that these poems were actually by Onomacritos who lived in the 50th Olympiad in the reign of the Peisistratidae. The line in those days between writing poems of your own and editing those of other people was less sharply drawn than it is to-day. Onomacritos had every temptation to interpolate, for he himself wrote poems on the rites of Dionysos. Pausanias in explaining the presence of the Titan Anytos at Lycosura says:'Onomacritos took the name of the Titans from Homer and composed orgies for Dionysos and made the Titans the actual agents in the sufferings of Dionysos.'

Something then was done about 'Orpheus' in the time of the Peisistratidae as something was done about Homer, some work of editing, compiling, revising. What form precisely this work took is uncertain. What is certain is that somehow Orphism, Orphic rites and Orphic poems had, before the classical period, come to Athens. The effect of this Orphic spirit was less obvious, less widespread, than that of Homer, but perhaps more intimate and vital. We know it because Euripides and Plato are deepdyed in Orphism, we know it not only by the signs of actual influence, but by the frequently raised protest.

Orpheus, it has been established in the mouth of many witnesses, modified, ordered, 'rearranged' Bacchic rites. We naturally ask was this all? Did this man whose name has come down to us through the ages, in whose saintly and ascetic figure the early Church saw the prototype of her Christ, effect nothing more vital than modification? Was his sole mission to bring order and decorum into an orgiastic and riotous ritual?

Such a notion is a priori as improbable as it is false to actual fact. Externally Orpheus differs from Dionysos, to put it plainly, in this. Dionysos is drunken, Orpheus is utterly sober. But this new spirit of gentle decorum is but the manifestation, the outward shining of a lambent flame within, the expression of a new spiritual faith which brought to man at the moment he most needed it, the longing for purity and peace in this life, the hope of final fruition in the next.

Before proceeding to discuss in detail such records of actual Orphic rites as remain, this new principle must be made clear. Apart from it Orphic rites lose all their real sacramental significance and lapse into mere superstitions.

Cardinal Doctrine of Orphism

The whole gist of the matter may thus be summed up. Orpheus took an ancient superstition, deep-rooted in the savage ritual of Dionysos, and lent to it a new spiritual significance. The old superstition and the new faith are both embodied in the little Orphic text that stands at the head of this chapter:

'Many are the wand-bearers, few are the Bacchoi.'

Can we be sure that this is really an Orphic text or was it merely a current proverb of any and every religion and morality? Plato says: 'Those who instituted rites of initiation for us said of old in parable that the man who came to Hades uninitiated lay in mud, but that those who had been purified and initiated and then came thither dwell with the gods. For those who are concerned with these rites say, They that bear the wand are many, the Bacchoi are few.' Plato does not commit himself to any statement as to who'those who are concerned with these rites'were, but Olympiodorus commenting on the passage says: 'He (Plato) everywhere misuses the sayings of Orpheus and therefore quotes this verse of his, "Many are the wand-bearers, few are the Bacchoi," giving the name of wand-bearers and not Bacchoi to persons who engage in politics, but the name of Bacchoi to those who are purified.'

It has already been shown that the worshippers of Dionysos believed that they were possessed by the god. It was but a step further to pass to the conviction that they were actually identified with him, actually'became him. This was a conviction shared by all orgiastic religions, and one doubtless that had its rise in the physical sensations of intoxication. Those who worshipped Sabazios became Saboi, those who worshipped Kubebe became Kubeboi, those who worshipped Bacchos Bacchoi; in Egypt the worshippers of Osiris after death became Osiris. The mere fact of intoxication would go far to promote such a faith, but there is little doubt that it was fostered, if not originated, by the pantomimic character of ancient ritual. It has been seen that in the Thracian rites 'bull-voiced mimes' took part, Lycophron tells that the women who worshipped the bull-Dionysos wore horns. It is a natural primitive instinct of worship to try by all manner of disguise to identify yourself more and more with the god who thrilled you.

Direct evidence of this pantomimic element in the worship of Dionysos is not wanting, though unhappily it is of late date. In the course of the excavations on the west slope of the Acropolis, Dr Dorpfeld laid bare a building known to be an'lobaccheion/ superimposed on an ancient triangular precinct of Dionysos, that of Dionysos in the Limnae. On this site was discovered an inscription giving in great detail the rules of a thiasos of lobacchoi in the time of Hadrian. Among a mass of regulations about elections, subscriptions, feast-days, funerals of members and the like, come enactments about a sacred pantomime in which the lobacchoi took part. The divine persons to be represented were Dionysos, Kore, Palaemon, Aphrodite, Proteurhythmos, and the parts were distributed by lot.

The name Proteurhythmos, it will later be shown, marks the thiasos as Orphic, and thoroughly Orphic rather than Dionysiac are the regulations as to the peace and order to be observed. 'Within the place of sacrifice no one is to make a noise, or clap his hands, or sing, but each man is to say his part and do it in all quietness and order as the priest and the Archibacchos direct.' More significant still and more beautiful is the rule, that if any member is riotous an official appointed by the priest shall set against him who is disorderly or violent the thyrsos of the god. The member against whom the thyrsos is set up, must if the priest or the Archibacchos so decide leave the banquet hall. If he refuse, the'Horses'appointed by the priest shall take him and set him outside the gates. The thyrsos of the god has become in truly Orphic fashion the sign not of revel and license, but of a worship fair and orderly.

We have noted the quiet and order of the representation because it is so characteristically Orphic, but the main point is that in the worship of Dionysos we have this element of direct impersonation which helped on the conviction that man could, identify himself with his god. The term Bacchae is familiar, so familiar that we are apt to forget its full significance. But in the play of Euripides there are not only Bacchae, god-possessed women worshippers, but also a Bacchos, and about his significance there can be no mistake. He is the god himself incarnate as one of his own worshippers. The doctrines of possession and incarnation are complementary, god can become man, man can become god, but 'I the Bacchic religion lays emphasis rather on the one aspect that man can become god. The Epiphany of the Bacchos, it may be noted, is after a fashion characteristically Orphic; the beautiful stranger is intensely quiet, and this magical quiet exasperates Pentheus just as Orpheus exasperated the Maenads. The real old Bromios breaks out in the Epiphany of fire and thunder, in the bull-god and the madness of the end.

The savage doctrine of divine possession, induced by intoxication and in part by mimetic ritual, was it would seem almost bound to develope a higher, more spiritual meaning. We have already seen that the madness of Dionysos included the madness of the Muses and Aphrodite, but, to make any real spiritual advance, there was needed it would seem a man of spiritual insight and saintly temperament, there was needed an Orpheus. The great step that Orpheus took was that, while he kept the old Bacchic faith that man might become a god, he altered the conception of what a god was, and he sought to obtain that godhead by wholly different means. The grace he sought was not physical intoxication but spiritual ecstasy, the means he adopted not drunkenness but abstinence and rites of purification.

Immortality through Divinity

All this is by anticipation, to clear the ground; it will be abundantly proved when Orphic rites and documents known to be Orphic are examined. Before passing to these it may be well to emphasize one point the salient contrast that this new religious principle, this belief in the possibility of attaining divine life, presented to the orthodox Greek faith.

The old orthodox anthropomorphic religion of Greece made the gods in man's image, but, having made them, kept them aloof, distinct. It never stated in doctrine, it never implied in ritual, that man could become god. Nay more, against any such aspiration it raised again and again a passionate protest. To seek to become even like the gods was to the Greek the sin most certain to call down divine vengeance, it was'Insolence.'

Pindar is full of the splendour and sweetness of earthly life, but full also of its insuperable limitation. He is instant in warning against the folly and insolence of any attempt to outpass it. To one he says, 'Strive not thou to become a god'; to another, 'The things of mortals best befit mortality.'It is this limitation, this constant protest against any real aspiration, that makes Pindar, for all his pious orthodoxy, profoundly barren of any vital religious impulse. Orphic though he was in certain tenets as to a future life, his innate temperamental materialism prevents his ever touching the secret of Orphism 'werde was du bist,' and he transforms the new faith into an other-worldliness. He is compounded of 'Know thyself and 'Nothing too much.'' In all things,' he says, 'take measure by thyself.' 'It behoveth to seek from the gods things meet for mortals, knowing the things that are at our feet and to what lot we are born. Desire not, thou soul of mine, life of the immortals, but drink thy fill of what thou hast and what thou canst.'In the name of religion it is all a desperate unfaith. We weary of this reiterated worldliness. It is not that he beats his wings against the bars; he loves too well his gilded cage. The gods are to him only a magnificent background to man's life. But sometimes, just because he is supremely a poet, he is ware of a sudden sheen of glory, an almost theatrical stage effect lighting the puppet show. It catches his breath and ours. But straightway we are back to the old stock warnings against Tantalos, against Bellerophon, whose'heart is aflutter for things far off.'Only one thing he remembers, perhaps again because he was a poet, that winged Pegasos'dwelt for ever in the stables of the gods .'

The cardinal doctrine of Orphic religion was then the possibility of attaining divine life. It has been said by some that the great contribution of Dionysos to the religion of Greece was the hope of immortality it brought. Unquestionably the Orphics believed in a future life, but this belief was rather a corollary than of the essence of their faith. Immortality, immutability, is an attribute of the gods. As Sophocles says:

'Only to gods in heaven

Comes no old age nor death of anything,

All else is turmoiled by our master Time.'

To become a god was therefore incidentally as it were to attain immortality. But one of the beautiful things in Orphic religion was that the end completely overshadowed the means. Their great concern was to become divine now. That could only be attained by perfect purity. They did not so much seek purity that they might become divinely immortal, they needed immortality that they might become divinely pure. The choral songs of the Bacchae are charged with the passionate longing after purity, in the whole play there is not one word, not one hint, of the hope of immortality. Consecration, perfect purity issuing in divinity, is, it will be seen, the keynote of Orphic faith, the goal of Orphic ritual.