|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER X.

ORPHIC MYSTERIES.

THE OMOPHAGIA.

Zagreus | The Titans | The Mountain Mother | The Kouretes | Hosioi and Hosia | Orphic Asceticism | Aristophanes on Orphism | The Liknophoria | The Sacred Marriage | The Oath of the Celebrants | Orphic Elements In Eleusinian Ritual | Iacchos at Eleusis | The Liknophoria at Eleusis | The Sacred Marriage and the Sacred Birth at Eleusis | Thessalian influence at Eleusis. Brimo, Eumolpos | The Delphic Dionysos at Eleusis and Agrae | The Greater and Lesser Mysteries | Delphic Influence at Eleusis | Crete and the Mysteries

THE most important literary document extant on Orphic ceremonial is a fragment of the Cretans of Euripides, preserved for us by Porphyry in his treatise on 'Abstinence from Animal Food' a passage Porphyry says he had'almost forgotten to mention.'

From an allusion in Aristophanes to 'Cretan monodies and unhallowed marriages' it seems probable that the Cretans dealt with the hapless wedlock of Pasiphae, The fragment, Porphyry tells us, was spoken by the chorus of Cretan mystics who have come to the palace of Minos. It is possible they may have come to purify it from the recent pollution.

The mystics by the mouth of their leader make full and definite confession of the faith, or rather acknowledgement of the ritual acts, by which a man became a 'Bacchos,' and they add a statement of the nature of the life he was thereafter bound to lead. Though our source is a poetical one, we learn from it, perhaps to our surprise, that to become a 'Bacchos' it was necessary to do a good deal more than dance enthusiastically upon the mountains. The confession runs as follows:

'Lord of Europa's Tyrian line,

Zeus-born, who boldest at thy feet

The hundred citadels of Crete,

I seek to thee from that dim shrine,

Hoofed by the Quick and Carven Beam,

By Chalyb steel and wild bull's blood

In flawless joints of cypress wood

Made steadfast. There in one pure stream

My days have run, the servant I,

Initiate, of Idaean Jove;

Where midnight Zagreus roves, I rove;

I have endured his thunder-cry:

Fulfilled his red and bleeding feasts;

Held the Great Mother's mountain flame;

I am Set Free and named by name

A Bacchos of the Mailed Priests.

Robed in pure white I have borne me clean

From man's vile birth and coffined clay,

And exiled from my lips alway

Touch of all meat where Life hath been.'

This confession must be examined in detail.

The first avowal is:

'the servant I,

Initiate, of Idaean Jove.'

It is remarkable that the mystic, though he becomes a 'Bacchos' avows himself as initiated to Idaean Zeus. But this Idaean Zeus is clearly the same as Zagreus, the mystery form of Dionysos. Zeus, the late comer, has taken over an earlier worship, the nature of which will become more evident after the ritual has been examined.

Zeus has in a sense supplanted Zagreus, but only by taking on his nature. An analogous case has already been discussed in dealing with Zeus Meilichios. At a time when the whole tendency of theology, of philosophy and of poetry was towards monotheism these fusions were easy and frequent. Of such a monotheistic divinity, half Zeus, half Hades, wholly Ploutos, we are told in another fragment of Euripides preserved by Clement of Alexandria. His ritual is that of the earth-gods.

Ruler of all, to thee I bring libation

And honey cake, by whatso appellation

Thou wouldst be called, or Hades, thou, or Zeus,

Fireless the sacrifice, all earth's produce

I offer. Take thou of its plenitude,

For thou amongst the Heavenly Ones art God,

Dost share Zeus'sceptre, and art ruling found

With Hades o'er the kingdoms underground.'

Zagreus

It has been conjectured that this fragment also is from the Cretans, but we have no certain evidence. Clement says in quoting the passage that'Euripides, the philosopher of the stage, has divined as in a riddle that the Father and the Son are one God.' Another philosopher before Euripides had divined the same truth, and he was Orpheus, only he gave to his Father and Son the name of Bacchos, and, all important for our purpose, gave to the Son in particular the title of Zagreus.

In discussing the titles of Dionysos, it has been seen that the names Bromios, Braites, Sabazios, were given to the god to mark him as a spirit of intoxication, of enthusiasm. The title Zagreus has been so far left unconsidered because it is especially an Orphic name. Zagreus is the god of the mysteries, and his full content can only be understood in relation to Orphic rites.

Zagreus is the mystery child guarded by the Kouretes, torn in pieces by the Titans. Our first mention of him is a line preserved to us from the lost epic the Alcmaeonis, which ran as follows:

Holy Earth and Zagreus greatest of all gods.'

The name of Zagreus never occurs in Homer, and we are apt to think that epic writers were wholly untouched by mysticism. Had the Alcmaeonis not been lost, we might have had occasion to modify this view. It was an epic story the subject-matter of which was necessarily a great sin and its purification, and though primarily the legend of Alcmaeon was based, as has been seen, on a curiously physical conception of pollution, it may easily have taken on Orphic developments. Zagreus appears little in literature; he is essentially a ritual figure, the centre of a cult so primitive, so savage that a civilized literature instinctively passed him by, or at most figured him as a shadowy Hades.

But religion knew better. She knew that though Dionysos as Bromios, Braites, Sabazios, as god of intoxication, was much, Dionysos as Zagreus, as Nyktelios, as Isodaites, he of the night, he who is'a meal shared by all'was more. The Orphics faced the most barbarous elements of their own faith and turned them not only qua theology into a vague monotheism, but qua ritual into a high sacrament of spiritual purification. This ritual, the main feature of which was'the red and bleeding feast,'must now be examined.

The avowal of the first certain ritual act performed comes in the line where the mystic says

I have

Fulfilled his red and bleeding feasts

The victim in Crete was a bull.

The shrine of Idaean Zeus, from which the mystics came, was cemented with bulls' blood . Possibly this may mean that at its foundation a sacred bull was slain and his blood mixed with the mortar; anyhow it indicates connection with bull-worship. The characteristic mythical monster of Crete was the bull-headed Minotaur. Behind the legend of Pasiphae, made monstrous by the misunderstanding of immigrant conquerors, it can scarcely be doubted that there lurks some sacred mystical ceremony of ritual wedlock with a primitive bull-headed divinity. He need not have been imported from Thrace; zoomorphic naturegods spring up everywhere. The bull-Dionysos of Thrace when he came to Crete found a monstrous god, own cousin to himself.

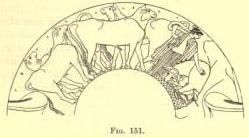

Such a monstrous god is depicted on

the curious seal-impression found by Mr Arthur Evans at Cnossos

and reproduced in fig. 146. He is seated on a throne of

camp-stool shape, and before hinnj stands a human figure,

probably a worshipper. That the monster is a god seems clear from

the fact that he is seated; that he is a bull-god is not so

certain. The head is not drawn with sufficient exactness for us

to be sure what beast is intended. He has certainly no horns, but

the hoof and tail might be those of a bull. The seal-impressions

found by Mr Hogarth in such large numbers at Zakro show how

widespread in Crete were these fantastic forms. The line between

man and beast is a faint one.

Such a monstrous god is depicted on

the curious seal-impression found by Mr Arthur Evans at Cnossos

and reproduced in fig. 146. He is seated on a throne of

camp-stool shape, and before hinnj stands a human figure,

probably a worshipper. That the monster is a god seems clear from

the fact that he is seated; that he is a bull-god is not so

certain. The head is not drawn with sufficient exactness for us

to be sure what beast is intended. He has certainly no horns, but

the hoof and tail might be those of a bull. The seal-impressions

found by Mr Hogarth in such large numbers at Zakro show how

widespread in Crete were these fantastic forms. The line between

man and beast is a faint one.

Mr Hogarth holds that the majority of these sealings have nothing to do with cults they are the product, he thinks, of an art which has'passed from monsters with a meaning to monsters of pure fancy.'He excepts however certain sealings where a Minotaur is represented, a monster with horned bull-head, pronounced bovine ears and tail, but apparently human trunk, arms and legs.

Like the monster in fig. 146, this Minotaur is seated, but with his left leg crossed human-fashion over his right knee and with human hands extended.

The traditional Minotaur took year by year his tale of human victims. Of the ritual of the bull-god in Crete, we know that it consisted in part of the tearing and eating of a bull, and behind is the dreadful suspicion of human sacrifice.

Part of the avowal of the Cretan mystic is that he has accomplished the rite of 'the feast of raw flesh.' That a feast of raw flesh of some sort was traditionally held to be a part of Bacchic ceremonial, is clear from the words Euripides put into the mouth of his Maenads:

'The joy of the red quick fountains,

The blood of the hill-goat torn,'

where the expression in the original, 'joy in eating raw flesh,' admits of no doubt.

An integral part of this terrible ritual was the tearing asunder of the slain beast, in order, no doubt, to get the flesh as raw as might be, for the blood is the life. Plutarch, in his horrified protest against certain orgiastic rites, joins the two ritual acts together, the'eatings of raw flesh'and the 'rendings asunder' 'There are certain festivals' he says, 'and sacrificial ceremonies as well as unlucky and gloomy days, in which take place eatings of raw flesh and rendings asunder, and fastings and beatings of the breast, and again disgraceful utterances in relation to holy things, and mad ravings and yells upraised with a loud din and tossing of the neck to and fro.' These ceremonies, he goes on to explain, are, to his thinking, not performed in honour of any god, but'they are propitiations and appeasements performed with a view to the riddance of mischievous demons; such also, he says, were the human sacrifices performed of old.' Plutarch's words read like a commentary on the Orphic ritual under discussion: we have the fasting, we have the horrid feast; he sees the savage element of 'riddance' but he misses the saving grace of enthusiasm and mystic significance.

If the sympathetic religious-minded Plutarch was horrified at a ritual so barbarous, it filled the Christian Fathers with unholy joy. Here was an indefeasible argument against paganism, and for once they compel our reluctant sympathy. 'I will not', cries Clement, dance out your mysteries, as they say Alcibiades did, but I will strip them naked, and bring them out on to the open stage of life, in view of those who are the spectators at the drama of truth. The Bacchoi hold orgies in honour of a mad Dionysos, they celebrate a divine madness by the Eating of Raw Flesh, the final accomplishment of their rite is the distribution of the flesh of butchered victims, they are crowned with snakes, and shriek out the name of Eva, that Eve through whom sin came into the world, and the symbol of their Bacchic orgies is a consecrated serpent'. And again: 'the mysteries of Dionysos are wholly inhuman; for while he was still a child and the Kouretes were dancing their armed dance about him, the Titans stole upon him, deceived him with childish toys and tore him to pieces'.

Arnobius pretends that the Bacchanalia are so horrible he must pass them by, and then goes on to revel in revolting detail over the rites'which the Greeks call Feasts of Raw Flesh in which with feigned frenzy and loss of a sane mind you twine snakes about you, and, to show yourselves full of the divinity and majesty of the god, you demolish with gory mouths the entrails of goats bleating for mercy.' The gentle vegetarian Porphyry knows that in Chios, according to tradition, there had been a Dionysos called Omadius, the Raw One, and that the sacrifice he used to exact was the tearing of a man to pieces. Istros stated that of old the Kouretes sacrificed children to Kronos. On Kronos all human sacrifice was apt to be fathered, but the mention of the Kouretes, coupled with the confession of the Cretan mystic, shows that the real divinity is Zagreus.

To these vague though consistent traditions of the eating and tearing of raw flesh, whether of man or goat or calf, in honour of some form of Dionysos, evidence more precise and definitely descriptive of Cretan ritual has been left us, again by a Christian Father, Firmicus Maternus. The festival he describes was, like many others in honour of Dionysos, trieteric, i.e. celebrated each alternate year.

Firmicus in the fashion of his day gives first a long and purely aetiological narrative of the death of the son of a king of Crete, to appease whose wrath the ceremony, it was believed, was instituted.'The Cretans commemorated the death of the boy by certain ceremonies, doing all things in regular order which the boy did or suffered.' These ceremonies included an enactment of the scene of the child playing with the toys and surprised by the Titans, and perhaps originally the slaying and tearing to pieces of a real child, but in the festival as described by Firmicus a bull was surrogate.'They tear in pieces a live bull with their teeth and by howling with discordant shouts through the secret places of the woods they simulate the madness of an enraged mind.'

Firmicus, by his obviously somewhat inaccurate statement, has gone far to discredit his own testimony. After the performance of a religious ceremony that involved the tearing of a live bull's flesh by human teeth the surviving worshippers would be few. But, because of this exaggeration, we need not discredit the whole ritual of the bull-slaying, nor the tearing and eating of raw, though not actually living, flesh. The bull indeed comes in so awkwardly in the midst of the aetiological story of the child, that we may be practically sure this account of a bygone ritual is authentic.

Some light is thrown on the method, and much on the meaning, of the horrible feast by an account left us by S. Nilus, a hermit of Mt. Sinai in the 4th century, of the sacrifice of a camel among the Arabs of his time. S. Nilus seems to have spent some of his abundant leisure in the careful examination of the rites and customs of the heathen around, and it is much to be regretted that in his 'Narrations' he has not recorded more of his observations. The nomadic condition of the Arabs about Sinai impressed him much; he notes that they are without trade, arts or agriculture, and if other food failed them, fed on their camels and only cooked the flesh just enough to enable them to tear it with their teeth. They worshipped no god, either in spirit or through an image made by hands, but sacrificed to the morning star at its rising. They by preference sacrificed boys in the flower of their age and of special beauty, and slew them at dawn on a rude heap of piled-up stones. He pathetically observes that this practice of theirs caused him much anxiety; he was nervous lest they should take a fancy to a beautiful young boy convert he had with him and sacrifice'his pure and lovely body to unclean demons.'But, he goes on,'when the supply of boys was lacking, they took a camel of white colour and otherwise faultless, bent it down upon its knees, and went circling round it three times in a circuitous fashion. The leader of the song and of the procession to the star was either one of their chiefs or a priest of special honour. He, after the third circuit had been made, and before the worshippers had finished the song, while the last words were still on their lips, draws his sword and smites the neck of the camel and eagerly tastes of the blood. The rest of them in like fashion run up and with their knives some cut off a small bit of the hide with its hairs upon it, others hack at any chance bit of flesh they can get. Others go on to the entrails and inwards and leave no scrap of the victim uneaten that might be seen by the sun at its rising. They do not refrain even from the bones and marrow, but overcome by patience and perseverance the toughness of the resistance'.

The account of Nilus leaves no doubt as to the gist of the ceremony: the worshippers aim at devouring the victim before the life has left the still warm blood. Raw flesh, Prof. Robertson Smith points out, is called in Hebrew and Syriac'living 'flesh.' Thus, in the most literal way, all those who shared in the ceremony absorbed into themselves part of the victim's life.

For live bull then we substitute raw bull, and the statement of Firmicus presents no difficulties. Savage economy demands that your juju, whatever it may be, should be as fresh as possible. Probably, at first, the bull may have been eaten just for the sake of absorbing its strength, without any notion of a divine sacrament.

The idea that by eating an animal you absorb its qualities is too obvious a piece of savage logic to need detailed illustration. That the uneducated and even the priestly Greek had not advanced beyond this stage of sympathetic magic is shown by a remark of Porphyry's. He wants to prove that the soul is held to be affected or attracted even by corporeal substances of kindred nature, and of this belief he says we have abundant experience.

'At least,' he says,'those who wish to take unto themselves the spirits of prophetic animals, swallow the most effective parts of them, such as the hearts of crows and moles and hawks, for so they possess themselves of a spirit present with them and prophesying like a god, one that enters into them themselves at the time of its entrance into the body. If a mole's heart can make you see into dark things, great virtue may be expected from a piece of raw bull. It is not hard to see how this savage theory of communion would pass into a higher sacramentalism, into the faith that by partaking of an animal who was a divine vehicle you could enter spiritually into the divine life that had physically entered you, and so be made one with the god. It was the mission of Orphism to effect these mystical transitions.

Because a goat was torn to pieces by Bacchants in Thrace, because a bull was, at some unknown date, eaten raw in Crete, we need not conclude that either of these practices regularly obtained in civilized Athens. The initiated bull-eater was certainly known of there, and the notion must have been fairly familiar, or it would not have pointed a joke for Aristophanes. In the audacious prorrhesis of the Frogsthe uninitiated are bidden to withdraw, and among them those

'Who never were trained by bull-eating Kratinos

In mystical orgies poetic and vinous.'

The worship of Dionysos of the Raw Flesh must have fallen into abeyance in Periclean Athens; but though civilized man, as a rule, shrinks from raw meat, yet, given imminent peril to rouse the savage in man, even in civilized man the faith in Dionysos Omestes burns up afresh. Hence stories of human sacrifice on occasions of great danger rise up and are accepted as credible. Plutarch, narrating what happened before the battle of Salamis, writes as follows: 'As Themistocles was performing the sacrifice for omens alongside of the admiral's trireme, there were brought to him three captives of remarkable beauty, attired in splendid raiment and gold ornaments; they were reputed to be the sons of Artayktes and Sandauke sister to Xerxes. When Euphrantides the soothsayer caught sight of them,and observed that at the same moment a bright flame blazed out from the burning victims, and at the same time a sneeze from the right gave a sign, he took Themistocles by the hand and bade consecrate and sacrifice all the youths to Dionysos Omestes, and so make his prayer, for thus both safety and victory would ensue to the Greeks. Themistocles was thunderstruck at the greatness and strangeness of the omen, it being such a thing as was wont to occur at great crises and difficult issues, but the people, who look for salvation rather by irrational than rational means, invoked the god with a loud shout together, and bringing up the prisoners to the altar imperatively demanded that the sacrifice should be accomplished as the seer had prescribed. These things are related by Phanias the Lesbian, a philosopher not unversed in historical matters.' Phanias lived in the 4th century B.C. Plutarch evidently thought him a respectable authority, but the fragments of his writings that we possess are all of the anecdotal type, and those which relate to Themistocles are evidently from a hostile source. His statement, therefore, cannot be taken to prove more than that a very recent human sacrifice was among the horrors conceivably possible to a Greek of the 4th century B.C., especially if the victim were a 'barbarian.'

The suspicion is inevitable that behind the primitive Cretan rites of bull-tearing and bull-eating there lay an orgy still more hideous, the sacrifice of a human child. A vase-painting in the British Museum, too revolting for needless reproduction here, represents a Thracian tearing with his teeth a slain child, while the god Dionysos, or rather perhaps we should say Zagreus, stands by approving. The vase is not adequate evidence that human children were slain and eaten, but it shows that the vase-painter of the 5th century B.C. believed such a practice was appropriate to the worship of a Thracian god.

A very curious account of a sacrifice to Dionysos in Tenedos helps us to realize how the shift from human to animal sacrifice, from child to bull or calf, may have come about. Aelian in his book on the Nature of Animals makes the following statement: 'The people of Tenedos in ancient days used to keep a cow with calf, the best they had, for Dionysos, and when she calved, why, they tended her like a woman in child-birth. But they sacrificed the new born calf, having put cothurni on its feet. Yes, and the man who struck it with the axe is pelted with stones in the holy rite and escapes to the sea.'The conclusion can scarcely be avoided that here we have a ritual remembrance of the time when a child was really sacrificed. A calf is substituted but it is humanized as far as possible, and the sacrificer, though he is bound to sacrifice, is guilty of an outrage Anyhow, that the calf was regarded as a child is clear; the line between human and merely animal is to primitive man a shifting shadow.

The mystic in his ritual confession clearly connects his feast of raw flesh with his service of Zagreus:

Where midnight Zagreus roves, I rove;

I have endured his thunder-cry;

Fulfilled his red and bleeding feasts.'

It remains to consider more closely the import of the sacred legend of Zagreus.

That the legend as well as the rite was Cretan and was connected with Orpheus is expressly stated by Diodorus. In his account of the various forms taken by the god Dionysos, he says 'they allege that the god (i.e. Zagreus) was born of Zeus and Persephone in Crete, and Orpheus in the mysteries represents him as torn in pieces by the Titans.

When a people has outgrown in culture the stage of its own primitive rites, when they are ashamed or at least a little anxious and self-conscious about doing what yet they dare not leave undone, they instinctively resort to mythology, to what is their theology, and say the men of old time did it, or the gods suffered it. There is nothing like divine or very remote human precedent. Hence the complex myth of Zagreus. When precisely this myth was first formulated it is impossible to say; it comes to us in complete form only through late authors. It was probably shaped and re-shaped to suit the spiritual needs of successive generations. The story as told by Clement and others is briefly this: the infant god variously called Dionysos and Zagreus was protected by the Kouretes or Korybantes who danced around him their armed dance. The Titans desiring to destroy him lured away the child by offering him toys, a cone, a rhombos, and the golden apples of the Hesperides, a mirror, a knuckle bone, a tuft of wool. The toys are variously enumerated. Having lured him away they set on him, slew him and tore him limb from limb. Some authorities add that they cooked his limbs and ate them. Zeus hurled his thunderbolts upon them and sent them down to Tartaros. According to some authorities, Athene saved the child's heart, hiding it in a cista. A mock figure of gypsum was set up, the rescued heart placed in it and the child brought thereby to life again. The story was completed under the influence of Delphi by the further statement that the limbs of the dismembered god were collected and buried at Delphi in the sanctuary of Apollo.

The monstrous complex myth is obviously aetiological through and through, the kernel of the whole being the ritual fact that a sacrificial bull, or possibly a child, was torn to pieces and his flesh eaten. Who tore him to pieces? In actual fact his worshippers, but the myth-making mind always clamours for divine precedent. If there was any consistency in the mind of the primitive mythologist we should expect the answer to be 'holy men or gods,' as an example. Not at all. In a sense the worshipper believes the sacrificial bull to be divine, but, brought face to face with the notion of the dismemberment of a god, he recoils. It was primitive bad men who did this horrible deed. Why does he imitate them? This is the sort of question he never asks. It might interfere with the pious practice of ancestral custom, and custom is ever stronger than reason. So he goes on weaving his aetiological web. He eats the bull; so the bad Titans must have eaten the god.. But, as they were bad, they must have been punished; on this point primitive theology is always inexorable. So they were slain by Zeus with his thunderbolts.

Other ritual details had of course to be worked in. The Kouretes, the armed Cretan priests, had a local war or mystery dance: they were explained as the protectors of the sacred child. Sacred objects were carried about in cistae; they were of a magical sanctity, fertility-charms and the like. Some ingenious person saw in them a new significance, and added thereby not a little to their prestige; they became the toys by which the Titans ensnared the sacred baby. It may naturally be asked why were the Titans fixed on as the aggressors? They were of course known to have fought against the Olympians in general, but in the story of the child Dionysos they appear somewhat as bolts from the blue. Their name even, it would seem, is aetiological, and behind it lies a curious ritual practice.

The Dionysiaca of Nonnus is valuable as a source of ritual and constantly betrays Orphic influence. From it we learn in many passages that it was the custom for the mystae to bedaub themselves with a sort of white clay or gypsum. This gypsum was so characteristic of mysteries that it is constantly qualified in Nonnus by the epithet 'mystic.' The technical terms for this ritual act of bedaubing with clay were 'to besmear' and 'to smear off', and they are used as roughly equivalent for 'to purify.' Harpocration has an interesting note on the word 'smear off'.' Others use it in a more special sense, as for example when they speak of putting a coat of clay or pitch on those who are being initiated, as we say to take a cast of a statue in clay; for they used to besmear those who were being purified for initiation with clay and pitch. In this ceremony they were mimetically enacting the myth told by some persons, in which the Titans, when they mutilated Dionysos, wore a coating of gypsum in order not to be identified. The custom fell into disuse, but in later days they were plastered with gypsum out of convention. Here we have the definite statement that in rites of initiation the worshippers were coated with gypsum. The 'some persons' who tell the story of Dionysos and the Titans are clearly Orphics. Originally, Harpocration says, the Titans were coated with gypsum that they might be disguised. Then the custom, by which he means the original object of the custom, became obsolete, but though the reason was lost the practice was kept up out of convention. They went on doing what they no longer understood.

The Titans

Harpocration is probably right. Savages in all parts of the world, when about to perform their sacred mysteries, disguise themselves with all manner of religious war-paint. The motive is probably, like most human motives, mixed; they partly want to disguise themselves, perhaps from the influence of evil spirits, perhaps because they want to counterfeit some sort of bogey; mixed with this is the natural and universal instinct to'dress up'on any specially sacred occasion, in order to impress outsiders. An element in what was at once a disguise and a decoration was coloured clay. Then having become sacred from its use on sacred occasions it became itself a sort of medicine, a means of purification and sanctification, as well as a ceremonial sign and token of initiation. Such performances went on not only in Crete but in civilized Athens. One of the counts brought by Demosthenes against Aeschines was, it will be remembered,'that he purified the initiated and wiped them clean with mud and pitch' with, be it noted, not from. Cleansing with mud does not seem to us a practical procedure, but we are back in the state of mind fully discussed in an earlier chapter, when purification was not physical cleansing in our sense of the word, but a thing at once lower and higher, a magical riddance from spiritual evil, from evil spirits and influences. For this purpose clay and pitch were highly efficacious.

But what has all this to do with the Titans? Eustathius, commenting on the word Titan, lets us into the secret. We apply the word titanos in general to dust, in particular to what is called asbestos, which is the white fluffy substance in burnt stones. It is so called from the Titans in mythology, whom Zeus in the story smote with his thunderbolts and consumed to dust. For from them, the fine dust of stones which has got crumbled from excessive heat, so to speak Titanic heat, is called titanic, as though a Titanic penalty had been accomplished upon it. And the ancients call dust and gypsum titanos.

This explanation is characteristically Eustathian. In his odd confused way the Archbishop, as so often, divines a real connection, but inverts and involves it. The simple truth is that the Titan myth is a 'sacred story' invented to account for the ritual fact that Orphic worshippers, about to tear the sacred bull, daubed themselves with white clay, for which the Greek word was titanos: they are Titans, but not as giants, only as white-clad men. It is not exactly a false etymology, as the mythological Titan giant probably owed his name to the fact that he was clay-born, earth-born, like Adam, only of white instead of red earth; but it was of course a false connection of meaning.

That this connection of meaning, this association of white-claymen of the mysteries with primaeval giants, was late and fictitious is incidentally shown by the fact that it was fathered on Onomacritus. In the passage from Pausanias already quoted, we are told that Onomacritus got the name of the Titans from Homer, and composed 'orgies' for Dionysos, and made the Titans the actual agents in the sufferings of Dionysos. He did not invent the white-clay worshippers, but he gave them a respectable orthodox Homeric ancestry. What confusion and obscurity he thereby introduced is seen in the fact that a bad mythological precedent is invented for a good ritual act; all consistency was sacrificed for the sake of Homeric association.

But nothing, nothing, no savage rite, no learned mythological confusion, daunts the man bent on edification, the pious Orphic. The task of spiritualizing the white-clay-mei, the dismembered bull, was a hard one, but the Orphic thinker was equal to it. He has not only taken part in an absurd and savage rite, he has brooded over the real problems of man and nature. There is evil in the universe, human evil to which as yet he does not give the name of sin, for he is not engaged with problems of free-will, but something evil, something that mixes with and mars the good of life, and he has long called it impurity. His old religion has taught him about ceremonial cleansings and has brought him, through conceptions like the Keres, very near to some crude notion of spiritual evil. The religion of Dionysos has forced him to take a momentous step. It has taught him not only what he knew before that he can rid himself of impurity, but also that he can become a Bacchos, become divine. He seems darkly to see how it all came about, and how the old and the new work together. His forefathers, the Titans, though they were but 'dust and ashes,' dismembered and ate the god; they did evil, and good came of it; they had to be punished, slain with thunderbolts; but even in their ashes lived some spark of the divine; that is why he their descendant can himself become Bacchos. From these ashes he himself has sprung. It is only a little hope; there is all the element of dust and ashes from which he must cleanse himself; it will be very hard, but he goes back with fresh zeal to the ancient rite, to eat the bull-god afresh, renewing the divine within him.

Theology confirms his hope by yet another thought. Even; the wicked Titans, before they ate Dionysos, had a heavenly ancestry; they were children of old Ouranos, the sky-god, as well as of Ge, the earth-mother. His master Orpheus worshipped the sun.

Can he not too, believing this, purify himself from his earthly nature and rise to be the'child of starry heaven'? Perhaps it is not a very satisfactory theory of the origin of evil; but is the sacred legend of the serpent and the apple more illuminating? Anyhow it was the faith and hope the Orphic, as we shall later see, carried with him to his grave.

There were other difficulties to perplex the devout enquirer. The god in the mysteries of Zagreus was a bull, but in the mysteries of Sabazios (p. 419) his vehicle was a snake, and these mysteries must also enshrine the truth. Was the father of the child a snake or a bull; was the horned child'a horned snake? It was all very difficult. He could not solve the difficulty; so he embodied it in a little dogmatic verse, and kept it by him as a test of reverent submission to divine mysteries:

'The Snake's Bull-Father the Bull's Father-Snake.'

The snake, the bull, the suake-bull-child 'not three Incomprehensibles, but one Incomprehensible.' On the altar of his Unknown God through all the ages man pathetically offers the holocaust of his reason.

The weak point of the Orphic was, of course, that he could not, would not, break with either ancient ritual or ancient mythology, could not trust the great new revelation which bade him become 'divine,' but must needs mysticize and reconcile archaic obsolete traditions. His strength was that in conduct he was steadfastly bent on purity of life. He could not turn upon the past and say, 'this daubing with white clay, this eating of raw bulls, is savage nonsense; give it up.' He could and did say, 'this daubing with white clay and eating of raw bulls is not in itself enough, it must be followed up by arduous endeavour after holiness.'

This is clear from the further confession of the Cretan chorus, to which we return. From the time that the neophyte is accepted as such, i.e. performs the initiatory rites of purification and thereby becomes a Mystes, he leads a life of ceremonial purity (dyvov). He accomplishes the rite of eating raw sacrificial flesh and also holds on high the torches to the Mountain Mother. These characteristic acts of the Mystes, are, I think, all preliminary stages to the final climax, the full fruition, when, cleansed and consecrated by the Kouretes, he is named by them a Bacchos, he is made one with the god.

The Mountain Mother

Before we pass to the final act consummated by the Kouretes, the place of the Mountain Mother has to be considered. The mystic's second avowal is that he has

'Held the Great Mother's mountain flame.'

In the myth of Zagreus, coming to us as it does through late authors, the child is all-important, the mother only present by implication. Zeus the late comer has by that time ousted Dionysos in Crete. The mythology of Zeus, patriarchal as it is through and through, lays no stress on motherhood. Practically the Zeus of the later Hellenism has no mother. But the bull-divinity worshipped in Crete was wholly the son of his mother, and in Crete most happily the ancient figure of the mother has returned after long burial to the upper air. On a Cretan seal Mr Arthur Evans found the beast-headed monster whom men called Minotaur; on a Cretan seal also he found the figure of the Mountain Mother, found her at Cnossos, the place of the birth of the bull-child, Cnossos overshadowed by Ida where within the ancient cave the holy child was born and the'mailed priests'danced at his birth.

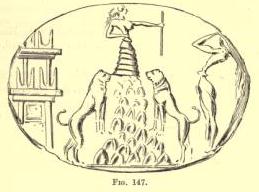

The design in fig. 147 is from the

clay impression of a signet ring found at the palace at Cnossos.

It is a veritable little manual of primitive Cretan faith and

ritual. On the very apex of her own great mountain stands the

Mountain Mother. The Mycenaean women of Cnossos have made their

goddess in their own image, clad her, wild thing though she was,

in their own grotesque flounced skirt, and they give her for

guardians her own fierce mountain-ranging lions, tamed into

solemn heraldic guardians. We know the lions well enough; they

came to Mycenae to guard the great entrance-gate. Between them at

Mycenae is a column, a thing so isolated and protected, that we

long suspected it was no dead architectural thing but a true

shrine of a divinity, and here on the Cretan seal the divinity

has come to life. She stands with sceptre or lance extended,

imperious, dominant. Behind her is her shrine of 'Mycenaean'

type, with its odd columns and horns, these last surely

appropriate enough to a cult whose central rite was the sacrifice

of a bull; before her in rapt ecstasy of adoration stands her

Mystes.

The design in fig. 147 is from the

clay impression of a signet ring found at the palace at Cnossos.

It is a veritable little manual of primitive Cretan faith and

ritual. On the very apex of her own great mountain stands the

Mountain Mother. The Mycenaean women of Cnossos have made their

goddess in their own image, clad her, wild thing though she was,

in their own grotesque flounced skirt, and they give her for

guardians her own fierce mountain-ranging lions, tamed into

solemn heraldic guardians. We know the lions well enough; they

came to Mycenae to guard the great entrance-gate. Between them at

Mycenae is a column, a thing so isolated and protected, that we

long suspected it was no dead architectural thing but a true

shrine of a divinity, and here on the Cretan seal the divinity

has come to life. She stands with sceptre or lance extended,

imperious, dominant. Behind her is her shrine of 'Mycenaean'

type, with its odd columns and horns, these last surely

appropriate enough to a cult whose central rite was the sacrifice

of a bull; before her in rapt ecstasy of adoration stands her

Mystes.

Pre-historic Crete has yielded, I venture to think will yield, no figure of a dominant male divinity, no Zeus; so far we have only a beast-headed monster and the Mountain Mother. The little seal impression is a standing monument of matriarchalism. In Greece the figure of the Son was developed in later days, the relation of Mother arid Son almost forgotten; child and parent were represented by the figures of the Mother and the Daughter. It matters very little what names we give the shifting pairs. In Thrace, in Asia Minor, in Crete, the primitive form is the Mother with the Son as the attribute of Motherhood; the later form the Son with the Mother as the attribute of Sonship. A further development is the Son with only a faded Mother in the background, Bacchos and Semele; next the Son is made the Son of his Father, Bacchos is Dionysos; finally he eclipses his Father and reigns omnipotent as Zeus-Hades. The Mother with the Son as attribute came back from Asia Minor to Greece when in Greece the Mother was but the appendage of the Son, and coming made sore confusion for mythology. But for prehistoric Crete, for the Cretan mystic of Euripides in the days of Minos, the ritual is of the Mother and the Son.

The Kouretes

The 'mystic' holds aloft the torches of the mother. Fire as well as water is for cleansing. He is finally consecrated (oaiwOefo) by the Kouretes:

'I am Set Free and named by name A Bacchos of the Mailed Priests.'

The Kouretes need not long detain us. They are the Cretan brothers of the Satyrs, the local Satyrs of Crete. Hesiod knows of their kinship: from the same parent

'The goddesses, nymphs of the mountain, had their being,

And the race of the worthless do-nothing Satyrs,

And the divine Kouretes, lovers of sport and dancing.'

Hesiod's words are noteworthy and characteristic of his theological attitude. The Satyrs, we have seen, are Satrai, primitive Dionysos-worshippers of Thrace and Thessaly. Seen through the hostile eyes of their conquerors they have suffered distortion and degradation in form as in content, they are horse-men, worthless, idle. The Kouretes have just the same beginning in actuality, but their mythological ending is different. They are seen, not through the distorting medium of conquest, but with the halo of religion about their heads; they are divine and their dancing is sacred. It all depends on the point of view.

Strabo, in his important discussion of the Kouretes and kindred figures, knows that they are all ministers of orgiastic deities, of Rhea and of Dionysos; he knows also that Kouretes, Korybantes, Daktyloi, Telchines and the like represent primitive populations. What bewilders him is the question which particular form originated the rest and where they all belong. Did Mother Rhea send her Korybants to Crete? how do the Kouretes come to be in Aetolia? Why are they sometimes servants of Rhea, sometimes of Dionysos? why are some of them magicians, some of them handicraftsmen, some of them mystical priests? In the light of Prof. Ridgeway's investigations, discussed in relation to the Satyrs, all that puzzled Strabo is made easy to us.

The Kouretes then are, as their name betokens, the young male population considered as worshipping the young male god, the Kouros', they are 'mailed priests' because the young male population were naturally warriors. They danced their local war-dance over the new-born child, and, because in those early days the worship of the Mother and the Son was not yet sundered, they were attendants on the Mother also. They are in fact the male correlatives of the Maenads as Nurses. The women-nurses were developed most fully, it seems, in Greece proper; the male attendants, in Asia Minor and the islands.

In the fusion and confusion of these various local titles given to primitive worshippers, this blend of Satyrs, Korybants, Daktyls, Telchines, so confusing in literature till its simple historical basis is grasped, one equation is for our purpose important Kouretes = Titans. The Titans of ritual, it has been shown, are men bedaubed with white earth. The Titans of mythology are children of Earth, primitive giants rebellious against the new Olympian order. Diodorus knows of a close connection between Titans and Kouretes and attempts the usual genealogical explanation. The Titans, he says, are, according to some, sons of one of the Kouretes and of a mother called Titaia; according to others of Ouranos and Ge. Titaia is mother Earth. The Cretans, he says, allege that the Titans were born in the age of the Kouretes and that the Titans settled themselves in the district of Cnossos 'where even now there are shown the site and foundations of a house of Rhea and a cypress grove dedicated from ancient days.' The Titans as Kouretes worshipped the Mother, and were the guardians of the Son, the infant Zagreus, to whom later monotheism gave the name of Zeus.

From the time that the neophyte enters the first stage of initiation, i.e. becomes a 'mystic', he leads a life of abstinence. But abstinence is not the end. Abstinence, the sacramental feast of raw flesh, the holding aloft of the Mother's torches, all these are but preliminary stages to the final climax, the full fruition when, cleansed and consecrated, he is made one with the god and the Kouretes name him 'Bacchos.'

The word 'pure,' in the negative sense, 'free from evil,' marks, I think, the initial stage a stage akin to the old service of 'aversion'. The word 'set free', 'consecrated', marks the final accomplishment and is a term of positive content. It is characteristic of orgiastic, 'enthusiastic' rites, those of the Mother and the Son, and requires some further elucidation.

Hosioi and Hosia

At Delphi there was an order of priests known as Hosioi. Plutarch is our only authority for their existence, but, for Delphic matters, we could have no better source. In his 9th Greek Question he asks 'who is the Hosioter among the Delphians, and why do they call one of their months Bysios?' The second part of the question only so far concerns us as it marks a connection between the Hosioter and the month Bysios, which, Plutarch tells us, was at the 'beginning of spring' the 'time of the blossoming of many plants.' On the 8th day of this month fell the birthday of the god and in olden times'on this day only did the oracle give answers.

Plutarch's answer to his question is as follows: 'They call Hosioter the animal sacrificed when a Hosios is designated.'He does not say how the animal's fitness was shown, but from another passage we learn that various tests were applied to the animals to be sacrificed, to see if they were 'pure, unblemished and uncorrupt both in body and soul.' As to the body Plutarch says it was not very difficult to find out. As to the soul the test for a bull was to offer him barley-meal, for a he-goat vetches; if the animal did not eat, it was pronounced unhealthy. A she-goat, being more sensitive, was tested by being sprinkled with cold water. These tests were carried on by the Hosioi and by the 'prophets', these last being concerned with omens as to whether the god would give oracular answers. The animal, we note, became Hosios when he was pronounced unblemished and hence fit for sacrifice: the word carried with it the double connotation of purity and consecration; it was used of a thing found blameless and then made over to, accepted by, the gods.

The animal thus consecrated was called Hosioter, which means 'He who consecrates.' We should expect such a name to be applied to the consecrating priest rather than the victim. If Plutarch's statement be correct, we can only explain Hosioter on the supposition that the sacrificial victim was regarded as an incarnation of the god. If the victim was a bull, as in Crete, and was regarded as divine, the title would present no difficulties.

That the Hosioter was not merely a priest is practically certain from the fact that there were, as already noted, priests who bore the cognate title of Hosioi. Of them we know, again from Plutarch, some further important particulars. They performed rites as in the case of the testing of the victims in conjunction with the 'prophets'or utterers of the oracle, but they were not identical with them. On one occasion, the priestess while prophesying had some sort of fit, and Plutarch mentions that not only did all the seers run away but also the prophet and'those of the Hosioi that were present.'

In the answer to his 'Question' about the Hosioter, Plutarch states definitely that the Hosioi were five in number, were elected for life, and that they did many things and performed sacred sacrifices with the'prophets.'Yet they were clearly not the same. A suspicion of the real distinction dawns upon us when he adds that they were reputed to be descended from Deucalion. Deucalion marks Thessalian ancestry and Thessaly looks North. We begin to surmise that the Hosioi were priests of the immigrant cult of Dionysos. This surmise approaches certainty when we examine the actual ritual which the Hosioi performed.

It will be remembered' that when Plutarch is describing the ritual of the Bull Dionysos, he compares it, in the matter of 'tearings to pieces' and burials and new births, to that of Osiris. Osiris has his tombs in Egypt and 'the Delphians believe that the fragments of Dionysos are buried near their oracular shrine, and the Hosioi offer a secret sacrifice in the sanctuary of Apollo at the time when the Thyiades wake up Liknites.' To clinch the argument Lycophron tells us that Agamemnon before he sailed

'Secret lustrations the Bull did make

Beside the caves of him the God of Gain

Delphinios,'

and that in return for this Bacchus Enorches overthrew Telephos, tangling his feet in a vine. The scholiast commenting on the 'secret lustrations' says, 'because the mysteries were celebrated to Dionysos in a corner.' It is, I think, clear that the mysteries of Liknites at Delphi, like those of Crete, included the sacrifice of a sacred bull, and that the bull at Delphi was called Hosioter, that, in a word, Hosioi and Hosioter are ritual terms specially linked with the primitive mysteries of Dionysos.

The word Hosios was then, it would seem, deep-rooted in the savage ritual of the Bull; but with its positive content, its notion of consecration, it lay ready to hand as a vehicle to express the new Orphic doctrine of identification with the divine. Its use was not confined to Dionysiac rites, though it seems very early to have been specialized in relation to them, probably because the Orphics always laid stress on fas rather than nefas. In ancient curse-formularies, belonging to the cult of Demeter and underworld divinities, the words 'consecrated and free' are used in constant close conjunction and are practically all but equivalents. The offender, the person cursed, was either 'sold' or 'bound down' to the infernal powers; but the cursing worshipper prays that the things that are accursed, i.e. tabooed to the offender, may to him be 'consecrated and free,' i.e. to him they are freed from the taboo. It is the dawning of the grace in use to-day 'Sanctify these creatures to our use and us to thy service'; it is the ritual forecast of a higher guerdon, 'Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.'

This primitive notion of release from taboo, which lay at the root of the Orphic and Christian notion of spiritual freedom, comes out very clearly in the use of the word aoaiovadai. For this word we have no exact English equivalent, but it may be rendered as'to purify by means of an expiatory offering.'Plato in the Laws describes the ceremonial to be performed in the case of a man who has intentionally murdered one near of kin. The regular officials are to put him to death, and this done'let them strip him, and cast him outside the city into a place where three ways meet, appointed for the purpose, and on behalf of the city collectively let the authorities, each one severally, take a stone and cast it on the head of the dead man, and thereby purify the city.' The significance of this ritual is drastically explicit. The taint of the murder, the taboo of the blood-guilt, is on the whole city; the casting of the stones, on behalf of the city, purifies it off on to the criminal; it is literally conveyed from one to other by the stone. The guilty man is the pharmakos, and his fate is that of a pharmakos;' this done let them carry him to the confines of the city, and cast him out unburied, as is ordained.' Dedication, devotion of the thing polluted, is the means whereby man attains consecration. The scholiast on the passage has an interesting gloss on the word consecration.' It is used', he says, 'as in this passage, to mean " to purify," or " to bring first-fruits," or " to give honour," or " to give a meed of honour on the occasion of death," or "to give fulfilment."' He feels dimly the shifts and developments of meaning. You can devote, 'make over 'a pharmakos; you can devote, consecrate first-fruits, thereby releasing the rest from taboo; you can consecrate a meed of honour on the occasion of death.

In this connection it is interesting to note the well-known fact that in common Greek parlance ootos is the actual opposite of iepos. Suidas tells us that a ocriov xwplov is 'a place on which you may tread, which is not sacred, into which you may go.' He quotes from the Lysistrata of Aristophanes, where a woman with child prays:

'O holy Eileithyia, keep back the birth

Until I come unto a place allowed'

He further notes the distinction often drawn by the orators between goods that are sacred and those that are (in the Latin sense) profane. The contrast is in fact only fully intelligible when we go back to the primitive notions, under a taboo, released from a taboo. The notion 'released from a taboo' was sure to be taken up by a spiritual religion, a religion that aimed at expansion, liberation, enthusiasm rather than at check, negation, restraint. If we may trust Suidas, the word qctioi was applied to those who 'were nurtured in piety, even if they were not priests.' The early Christians owed some of their noblest instincts to Orphism.

As we find ocrios contrasted with lepos, so also between the two kindred words caoaipa and oo-toay a distinction may be observed. Both denote purification, but ocrtoo marks a stage more final and complete. It is the word chosen to describe the state of those who are fully initiated. Plutarch says that the souls of men pass, by a natural and divine order, from mortal men to heroes, from heroes to daemons, and finally, if they are completely purified and consecrated, as if by a rite of initiation they pass from daemons to the gods. Lucian again in speaking of the final stage of initiation reserved for hierophants uses the word consecrated'.

Plutarch makes another interesting suggestion. In a wild attempt to glorify Osiris and make him the god of everything, he derives his name from the two adjectives ovtos and iepos, and incidentally lets fall this suggestive remark,'the name of Osiris is so compounded because his significance is compounded of things in heaven and things in Hades. It was customary among the ancients to call the one oaia the other iepd.' The things of the underworld are ocria; of the upper sky, things Ouranian, Iepd. Translated into ritual, this means that the old underworld rites already discussed, the rites of the primitive Pelasgian stratum of the population, were known as ocna, the new burnt sacrifices of the Ouranians or Olympians were Iepd. Dionysos was of the old order: his rites were ocria, burial rites were ocria. It was the work of Orpheus to lift these rites from earth to heaven, but spiritualized, uplifted as they are, they remain in their essence primitive. It is because of this peculiar origin that there is always about something of an antique air; it has that 'imprint of the ancient,' that 'crust and patina' of archaism, which lamblichus says were characteristic of things Pythagorean, and which, enshrining as it does a new life and impulse, lends to Orphism a grace all its own. Moreover, though ooos is so 'free' that it verges on the profane, the secular, yet it is the freedom always of consecration, not desecration; it is the negation of the Law, but only by the Gospel. Hence, though this may seem paradoxical, it is concerned rather with the Duty towards God, than the Duty towards our Neighbour. Rising though it does out of form, it is so wholly aloof from formalism, that it tends to become the 'unwritten law.' Hence such constant oppositions as 'allowed by neither human prescription nor divine law,' and again 'right neither in the eye of God nor of man.' Plato says'he who does what is proper in relation to man, would be said to do just things, he who does what is proper towards God, holy things.'Hence finally the spiritual illumination and advance of breaking through human Justice for the Divine Right, the duty, sacred, sacrosanct, of rebellion.

The Greeks had their goddess Dike, she who divides and apportions things mortal, who according to Hesiod was sister of the lovely human figures, Fair Order and Peace. But, because she was human, she carried the symbol of human justice, the sword. She lapses constantly into Vengeance. The Bacchants of Euripides are fully initiated, consecrated as well as cleansed, yet in their hour of extreme need it is to this Goddess of Vengeance they cry for visible, physical retribution on the blasphemer Pentheus:

'Hither for doom and deed,

Hither with lifted sword,

Justice, Wrath of the Lord,

Come in our visible need,

Smite till the throat shall bleed,

Smite till the heart shall bleed

Him the tyrannous, lawless, godless, Echion's earth-born seed.'

Orpheus did all he could to raise the conception of Dike. We are expressly told that it was he who raised her to be the 'Assessor of Zeus.' Demosthenes pleads with his fellow citizens to honour Fair Order, who loves just deeds and is the Saviour of cities and countries, and Justice (Dike), holy and unswerving, whom Orpheus who instituted our most sacred mysteries declares to be seated by the throne of Zeus. The dating of Orphic hymns is precarious, but it looks as though Demosthenes had in his mind the Orphic Hymn to Dike or at least its prototype:

'I sing the all-seeing eye of Dike of fair form,

Who sits upon the holy throne of Zeus

The king, and on the life of mortals doth look down,

And heavy broods her justice on the unjust.'

The Orphic could not rid himself of the notion of Vengeance. Dike as avenger finds a place, it will be seen later (p. 612), in the Orphic Hades. Hosia, the real Heavenly Justice, she who is Right and Sanctity and Freedom and Purity all in one, never attained a vivid and constant personality; she is a goddess for the few, not the many; only Euripides called her by her heavenly name and made his Bacchants sing to her a hymn:

'Thou Immaculate on high;

Thou Kecording Purity;

Thou that stoopest, Golden Wing,

Earthward, manward, pitying,

Hearest thou this angry king?'

It was Euripides, and perhaps only Euripides, who made the goddess Hosia in the image of his own high desire, and, though the Orphic word and Orphic rites constantly pointed to a purity that was also freedom, to a sanctity that was by union with rather than submission to the divine, yet Orphism constantly renounced its birth-right, reverted as it were to the old savage notion of abstinence. After the ecstasy of

'I am Set Free and named by name

A Bacchos of the Mailed Priests,'

the end of the mystic's confession falls dull and sad and formal:

'Kobed in pure white I have borne me clean

From man's vile birth and coffined clay,

And exiled from my lips alway

Touch of all meat where Life hath been.'

He that is free and holy and divine, marks his divinity by a dreary formalism. He wears white garments, he flies from death and birth, from all physical contagion, his lips are pure from flesh-food, he fasts after as before the Divine Sacrament. He follows in fact all the rules of asceticism familiar to us as 'Pythagorean'.

Orphic Asceticism

Diogenes Laertius in his life of Pythagoras gives a summary of these prescriptions, which show but too sadly and clearly the reversion to the negative purity of abstinence . 'Purification, they say, is by means of cleansings and baths and aspersions, and because of this a man must keep himself from funerals and marriages and every kind of physical pollution, and abstain from all food that is dead or has been killed, and from mullet and from the fish melanurus, and from eggs, and from animals that lay eggs, and from beans, and from the other things that are forbidden by those who accomplish holy rites of initiation.' The savage origin of these fastings and taboos on certain foods has been discussed; they are deep-rooted in the ritual of aTrorpoTrrf, of aversion, which fears and seeks to evade the physical contamination of the Keres inherent in all things. Plato, in his inverted fashion, realizes that the Orphic life was a revival of things primitive. In speaking of the golden days before the altars of the gods were stained with blood, when men offered honey cakes and fruits of the earth, he says then it was not holy to eat or offer flesh-food, but men lived a sort of 'Orphic' life, as it is called.

Poets and philosophers, then as now, sated and hampered by the complexities and ugliness of luxury, looked back with longing eyes to the old beautiful gentle simplicity, the picture of which was still before their eyes in antique ritual, in the ocna, the rites of the underworld gods those gods who in their beautiful conservatism kept their service cleaner and simpler than the lives of their worshippers. Sophocles' in the lost Polyidos tells of the sacrifice 'dear to these gods':

'Wool of the sheep was there, fruit of the vine,

Libations and the treasured store of grapes.

And manifold fruits were there, mingled with grain

And oil of olive, and fair curious combs

Of wax compacted by the yellow bee.'

Some of these gods, it has been seen, would not taste of the fruit of the vine: such were at Athens the Sun, the Moon, the Dawn, the Muses, the Nymphs, Mnemosyne and Ourania. To them the Athenians, who were careful in matters of religion, brought only sober offerings, nephalia; and such an offering we have seen was brought to Dionysos-Hades. Philochoros, to our great surprise, extends the list of wineless divinities to Dionysos. Plutarch knows the custom of the wineless libation to Dionysos, and after the fashion of his day explains it as an ascetic protest. In his treatise on the Preservation of Health' he says, 'We often sacrifice nephalia to Dionysos, accustoming ourselves rightly not to desire unmixed wine.' The practice is manifestly a survival in ritual of the old days before Dionysos took possession of the vine, or rather the vine took possession of him. Empedokles had taught men that'to fast from evil 'was a great and divine thing; it is not surprising that the'wineless' rites became to those who lived the Orphic life the symbol, perhaps the sacrament, of their spiritual abstinence. Plutarch we know was suspected by his robuster friends of Orphism, and probably with good reason. In his dialogue on 'Freedom from Anger' he makes one of the speakers, who is transparently himself, tell how he conquered his natural irritability. He set himself to observe certain days as sacred, on which he would not get angry, just as he might have abstained from getting drunk or taking any wine, and these 'angerless days' he offered to God as 'Nephalia' or 'Melisponda,' and then he tried a whole mouth, and then two, till he was cured. To a greater than Plutarch, a priest who was poet also, the wineless sacrifice of the Eumenides is charged with sacramental meaning; the rage of the king is over, in his heart is meekness, in his hands olive, shorn wool, water and honey; so only may he enter their sanctuary, he sober and they wineless.'

!ln the confession of the Orphic there is no mention of wine, no avowal of having sacramentally drunk it, no resolve to abstain. The Bacchos, with whom the mystic is made one, is the ancient Bull-god, lord of the life of Nature, rather than Bromios, god of intoxication. Also it must not be forgotten that the mystic is a votary of the Mother as well as the Son, and though the Mother is caught and carried away in the later revels of the Son, she is never goddess of the vine. It is noteworthy that the later Orphics turned rather to the Mother than the Son; they revived the ancient rite of earth to earth burial, supplanted for a time by cremation, and the house of Pythagoras was called by the people of Metapontum the 'temple of Demeter.' Pythagoras never insisted on 'total abstinence,' but he told his disciples that if they would drink plain water they would be clearer in head as well as healthier in body. In the ancient rites of the Mother, rites instituted before the coming of the grape, they found the needful divine precedent:

'Then Metaneira brought her a cup of honey-sweet wine,

But the goddess would not drink it, she shook her head for a sign,

For red wine she might not taste, and she bade them bring her meal

And water and mix it together, and mint that is soft to feel.

Metaneira did her bidding and straight the posset she dight,

And holy Deo took it and drank thereof for a rite.'

It is strange that Orpheus if he came from the North, the land of Homeric banquets, should have preached abstinence from flesh: if he was of Cretan origin the difficulty disappears. Perhaps also such abstinence is a necessary concomitant of a mysticism that asks for nothing short of divinity. The mystic Porphyry says clearly that his treatise on 'Abstinence from Animal Food' is not meant for soldiers or for athletes; for these flesh food may be needful. He writes for those who would lay aside every weight and 'entering the stadium naked and unclothed would strive in the Olympic contest of the soul.' And a great modern mystic, looking more deeply and more humbly into the mystery of things natural, writes as follows:

'Toute noire justice, toute notre morale, tons nos sentiments et toutes nos pensees derivent en somme de trois ou quatre besoins primordiaux, dont le principal est celui de la nourriture. La moindre modification de Vun de ces besoins amenerait des changements considerables dans notre vie morale! Maeterlinck believes, as Pythagoras did, that those who abstain from flesh food'ont senti leurs forces saccroitre, leur sante se retablir ou s'affermir, leur esprit Colleger et se purifier, comme au sortir dune prison seculaire nauseabonde et miserable!

But the plain carnal man in ancient Athens would have none of this. What to him are ocria, things hallowed to the god, as compared with voifia, things consecrated by his own usage? So Demosthenes taunts Aeschines, because he cries aloud 'Bad have I fled, better have I found'; so Theseus, the bluff warrior, hates Hippolytos, not only, or perhaps not chiefly, because he believes him to be a sinner, but because he is an Orphic, righteous overmuch. All his rage of flesh and blood breaks out against the prig and the ascetic.

'Now is thy day! Now vaunt thee; thou so pure,

No flesh of life may pass thy lips! Now lure

Fools after thee; call Orpheus King and Lord,

Make ecstasies and wonders! Thumb thine hoard

Of ancient scrolls and ghostly mysteries.

Now thou art caught and known. Shun men like these,

I charge ye all! With solemn words they chase

Their prey, and in their hearts plot foul disgrace.'

Happily there were in Athens also those who did not hate but simply laughed, laughed aloud genially and healthily at the outward absurdities of the thing, at all the mummery and hocus-pocus to which the lower sort of Orphic gave such solemn intent; Among these ge'nial scoffers was Aristophanes.

There is no more kindly and delightful piece of fooling than the scene in the Clouds in which he deliberately and in detail parodies the Orphic mysteries. The tension of Orphism is great; it is, like all mysticisms, a state of mind intrinsically and necessarily transient, and we can well imagine that, in his lighter moods, the most pious of Orphics might have been glad to join the general fun. In any case it helps us to realize vividly both the mise-en-scene of the mysteries themselves and the attitude of the popular mind towards them. Exactly what particular rite is selected for parody we do not know; probably some lesser mystery of purification, for there is no allusion to the supreme sacramental feast of bull's flesh nor to the idea that the neophyte is made one with the god.

The old unhappy father Strepsiades comes to the 'Thinking-Shop' of Sokrates that he may learn to evade his creditors by dexterity of speech and new-fangled sophistries in general. A disciple opens the door, with reluctance and warns Strepsiades that he cannot reveal these 'mysteries' to the chance comer Strepsiades enters and sees a number of other disciples lost in the contemplation of earth and heaven. He calls for Sokrates and is answered by a voice up in the air.

Why dost thou call me, Creature of a Day?

Str. First tell me please, what are you doing up there ?

Sok. I walk in air and contemplate the Sun.'

Here is the first Orphic touch. Sokrates instead of climbing a mountain has taken an easier way: he is suspended in a basket, and, Orpheus-like, reveres the Sun. The mysteries are not Eleusinian, not of the underworld. The comedian might and did dare to bring the Mystics of Kore and lacchos in Hades on the stage, but a direct parody of the actual ceremony of initiation at Eleusis would scarcely have been tolerated by orthodox Athens. The Eleusinian rites had become by that time a state religion, politically and socially sacred. The Orphics were Dissenters, and a parody of Orphic mysteries was an appeal at once to popular prejudice and popular humour. Sokrates explains that he is sitting aloft to avoid the intermixture of earthly elements in his contemplation; again we have a skit on the Orphic doctrine of the double nature of man, earthly and heavenly, and the need , for purification from earthly Titanic admixture.

After some preliminary nonsense Strepsiades tells his need, and Sokrates descends and asks:

'Now, would you fain

Know clearly of divine affairs, their nature

When rightly apprehended?

Str. Yes, if I may.

Sok. And would you share the converse of the Clouds,

The spiritual beings we worship?

Str. Why, yes, rather.

Sok. Then take your seat upon this sacred campstool.

Str. All right, I'm here.

Sok. And now, take you this wreath.

Str. A wreath what for ? Oh mercy, Sokrates,

Don't sacrifice me, I'm not Athamas !

Sok. No, no. I'm only doing just the things

We do at initiations.'

Strepsiades is of the old order; he knows nothing of these new ''spiritual beings' worshipped by Orphics and sophists. Something religious and uncomfortable is going to be done to him, and his thoughts instinctively revert to the old order. A wreath suggests a sacrificial victim,, and the typical victim is Athamas. Sokrates at once corrects him, and puts the audience on the right scent. It is not a common old-world sacrifice; it is an initiation 'into a new-fangled rite, in which, it would appear the mystic was crowned, probably by way of consecration to the gods. Strepsiades is not clear about the use of such things:

I Str. Well, what good

Shall I get out of it?

Sok. Why, just this, you'll be

A floury knave, uttering fine flowers of speech.

Now just keep still.

Str. By Jove, be sure you do it,

Come flour me well, I'll be a flowery knave.'

If any doubt were possible as to the nature of the ceremonies parodied, the words translated 'flour' to preserve the pun, settle the matter. The word rpia means something rubbed, pounded; the noise made in rubbing and founding; it might be rendered 'rattle.' Strepsiades is too become subtle in his arguments, a rattle in his speech. The words would have no sort of point but for the fact that Sokrates at the moment takes up two pieces of gypsum, pounds them to together and bespatters Strepsiades till he is white all over like a Cretan mystic. The scholiast is quite clear as to what was done on the stage.' Sokrates while speaking rubs together two friable stones, and beating them against each other collects the splinters and pelts the old man with them, as they pelt the victims with grain. He is quite right as to the thing done, quite wrong as to the ritual imitated. Strepsiades, as Sokrates said, is not being sacrificed; it is not the ritual of sacrifice that is mimicked, but of initiation.

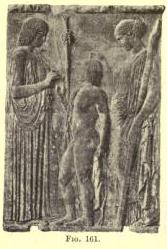

The certainty that the scene is one of initiation, not sacrifice, is made more certain by the fact that Strepsiades is sitting all the while, not on an altar, but on a sort of truckle-bed or camp-stool. We have no evidence of the use of this in mystic ritual, but it is clearly the comic equivalent of the seat or throne used in Orphic rites. The candidate for initiation, whether Eleusinian or Orphic, was always seated, and the ceremony was known as the'seating'or enthronement. Dion Chrysostom says those who perform initiation ceremonies are wont in the ceremony called 'the seating' to make the candidates sit down and to dance round them. It is to this ceremonial that Plato alludes in the Euthydemus. 'You don't see, Kleinias, that the two strangers are doing what the officials in the rites of the Korybantes are wont to do, when they perform the ceremony of "seating" for the man who is about to be initiated.' Kleinias is undergoing instruction like the neophyte in the mysteries; he has to sit in silence while his instructors dance argumentatively round him, uttering what seem to him unmeaning words.

Aristophanes on Orphism

So far Strepsiades is a mystic in the first stage of initiation, i.e. he is being prepared and purified. All this ceremonial is preliminary to the next stage, that of full vision. He is seated on the stool, he is covered with chalk, to one end only, and that is that he may behold clearly, may hold communion with, the heavenly gods. Sokrates, in regular ritual fashion, first proclaims the sacred silence, then makes preliminary prayer to the sophistic quasi-Orphic divinities of Atmosphere and Ether, and finally invokes the Holy Clouds in pseudo-solemn ritual fashion:

'Sok. Silence the aged man must keep, until our prayer be ended.

Atmosphere unlimited, who keepst our earth suspended,

Bright Ether and ye Holy Clouds, who send the storm and thunder,

Arise, appear above his head, a Thinker waits in wonder.

Str. Wait, please, I must put on some things before the rain has drowned me,

I left at home my leather cap and macintosh, confound me.

Sok. Come, come! Bring to this man full revelation.

Come, come! Whether aloft ye hold your station

On Olympus'holy summits, smitten of storm and snow,

Or in the Father's gardens, Okeanos, down below,

Ye weave your sacred dance, or ye draw with your pitchers gold

Draughts from the fount of Nile, or if perchance ye hold

Maiotis mere in ward, or the steep Mimantian height,

Snow-capped, hearken, we pray, vouchsafe to accept our rite

And in our holy meed of sacrifice take delight.'

The address is after the regular ritual pattern, which mentions, for safety's sake, any and every place where the divine beings are likely to wander. That such an invocation formed part of Orphic-Dionysiac rites is not only a priori probable but certain from the lacchos song in the Frogs. In a word the 'full revelation,' of these and all mysteries, was only an intensification, a mysticizing, of the old Epiphany rites the 'Appear, appear' of the Bacchants, the 'summoning' of the Bull-god by the women of Elis. It was this Epiphany, outward and inward, that was the goal of all purification, of all consecration, not the enunciation or elucidation of arcane dogma, but the revelation, the fruition, of the god himself. To what extent these Epiphanies were actualized by pantomimic performances we do not know; that some form of mimetic representation was enacted seems probable from the scene that follows the Epiphany of the Clouds, when Strepsiades confused and amazed gropes in bewilderment, and bit by bit attains clear vision of the goddesses.

That the new divinities are goddesses is as near as Aristophanes dare go to a skit on Eleusinian rites; that they are goddesses of the powers of the air, not dread underworld divinities, saves him from all scandal as regards his Established Church. He guards himself still further by making his Clouds, in one of their lovely little songs, chant the piety of Athens, home of the mysteries.

The Clouds themselves were as safe as they were poetical. Even the Orphics did not actually worship clouds; but their theogony, their cosmogony, is, as will later be seen, full of vague nature-impersonations, of air and ether and Erebos and Chaos, and the whirlpool of things unborn. No happier incarnation of all this, this and the vague confused cosmical philosophy it embodied, than the shifting wonder of mists and clouds.

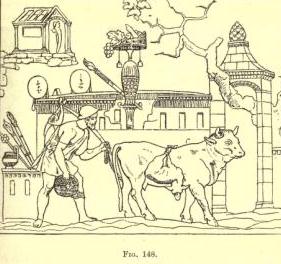

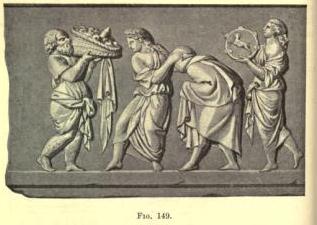

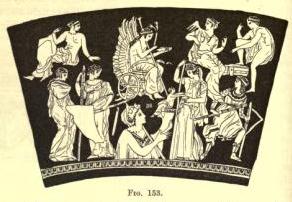

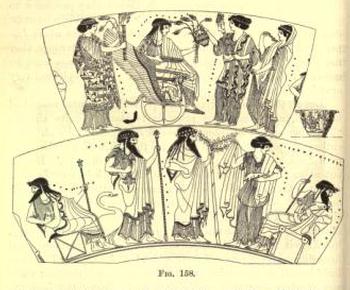

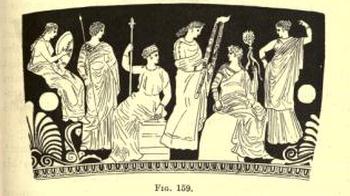

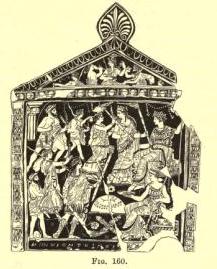

The scene, though it goes on far too long, must have been exquisitely comic. With no stage directions probably half the trivial and absurd details have been lost, but we can imagine that the whole hocus-pocus of an Orphic mystery was carefully mimicked. We can even imagine that Sokrates was dressed up as an initiating Silen, such a one as is depicted in the relief in fig. 149.

We can also imagine that in Athens it was hard to be an Orphic, a dissenter, a prig, a man overmuch concerned about his own soul. We have seen how against such eccentrics the advocate Demosthenes could appeal to the prejudices of a jury. We know that to Theophrastos it was the characteristic of a 'superstitious man' that he went every month to the priest of the Orphic mysteries to participate in these rites, and we gather dimly that he did not always find sympathy at home; his wife was sometimes 'too busy' to go with him, and he had to take the nurse and children.