|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER XI

ORPHIC ESCHATOLOGY.

THE ORPHIC TABLETS

The Well Of Mnemosyne | Lethe and Eunoe in Dante | The Ritual Formularies | Ritual of the Wheel | Ritual of the Circle | The Kid and the Milk | Primitive Baptism | Orphic Vases Of Lower Italy | Orpheus in Hades | Orpheus and Eurydice | Sisyphos | The Judges of Hades | Dike in Hades | The Danaides

THE monuments in question are a series of eight inscribed tablets all of very thin gold, which have come to light in tombs. Six out of the eight were found in Lower Italy, in the neighbourhood of ancient Sybaris, one near Rome, one in Crete. In the first and third cases, it should be noted, the place provenance is an ancient home of Orphism.

These tablets are of such cardinal

importance that they will need to be examined separately and in

detail. But all have this much in common: buried with the dead

they contain instructions for his conduct in the world below,

exhortations to the soul, formularies to be repeated, confessions

of faith and of ritual performed, and the like. They belong to

the domain of ritual rather than of literature, and therefore

offer evidence the more unimpeachable; but, though defective in

style and often regardless of metre, they are touched with a

certain ecstasy of conviction that lifts them sometimes to a high

level of poetry.

These tablets are of such cardinal

importance that they will need to be examined separately and in

detail. But all have this much in common: buried with the dead

they contain instructions for his conduct in the world below,

exhortations to the soul, formularies to be repeated, confessions

of faith and of ritual performed, and the like. They belong to

the domain of ritual rather than of literature, and therefore

offer evidence the more unimpeachable; but, though defective in

style and often regardless of metre, they are touched with a

certain ecstasy of conviction that lifts them sometimes to a high

level of poetry.

The Orphic tablets have frequently been discussed, but their full importance as documents for the history of Greek religion has perhaps as yet not been fully realized.

Their interpretation presents exceptional difficulties; the shining surface and creased condition of the gold-leaf on which they are written make them difficult to photograph and irksome to decipher; moreover the text, even when deciphered, is in some cases obviously fragmentary. It has been thought best to reserve all textual difficulties for separate discussion.

The series of tablets or scrolls is as follows:

I. The Petelia tablet (fig. 162).

'Thou shalt find on the left of the House of Hades a Well-spring,

And by the side thereof standing a white cypress.

To this Well-spring approach not near.

But thou shalt find another by the Lake of Memory,

Cold water flowing forth, and there are Guardians before it.

Say: " I am a child of Earth and of Starry Heaven;

But my race is of Heaven (alone). This ye know yourselves.

And lo, I am parched with thirst and I perish. Give me quickly

The cold water flowing forth from the Lake of Memory."

And of themselves they will give thee to drink from the holy Well-spring

And thereafter among the other Heroes thou shalt have lordship....'

The text breaks off at this point. The scattered words that remain make no consecutive sense. Of the last line, written from bottom to top of the right edge of the tablet, the two last words only are legible, 'darkness enfolding'

As sequel to this tablet comes a second found in Crete:

II. The Eleuthernae tablet.

'I am parched with thirst and I perish. Nay, drink of Me,

The well-spring flowing for ever on the Right, where the Cypress is.

Who art thou?

Whence art thou? I am son of Earth and of Starry Heaven.'

The soul itself speaks to the Well of Mnemosyne and the Well makes answer.

Both tablets contain the same two elements, the Well of Remembrance, and the avowal of origin. The avowal of origin constitutes in each the claim to drink of the Well.

The origin claimed is divine. Hesiod uses exactly the same words in describing the parentage of the gods. He bids the Muse

'Sing the holy race of Immortals ever existing,

Who from Earth were born and born from Starry Heaven.'

We have in the avowal of the soul the clearest possible statement of the cardinal doctrine of Orphic faith immortality is possible only in virtue of the divinity of humanity. The sacrament of this immortality is the drinking of a divine well.

The Well Of Mnemosyne

On the first tablet the soul is bidden to avoid a well on the left hand. This well is left nameless, but contrasted as it is with the Well of Mnemosyne or Remembrance, we may safely conclude that the forbidden well is Lethe, Forgetfulness.

The notion that in death we forget, forget the sorrows of this troublesome world, forget the toilsome journey to the next, is not Orphic, not even specially Greek; it is elemental, human, and may occur anywhere.

The Fiji islanders have their 'Path of the Shades' beset with perils and their Wai-na-dula, a well from which the dead man drinks and forgets sorrow.' He passed the twin goddesses Nino who peered at him and gnashed their terrible teeth, fled up the path and came to a spring and stopped and drank, and, as soon as he tasted the water, he ceased weeping, and his friends also ceased weeping in his home, for they straightway forgot their sorrows and were consoled. Therefore this spring is called the Wai-na-dula, Water of Solace.' After many other perils, including the escape from two savage Dictynnas who seek to catch him in their nets, the soul at last is allowed to pass into the dancing grounds where the young gods dance and sing.

This Fiji parallel is worth noting because it is so different. The Fiji soul drinks of forgetfulness, and why? Because his friends and relations must put a term to their irksome mourning, and till the soul sets the example and himself forgets they must remember. His confession of faith is also somewhat different. Before he can be admitted to his Happy Land he must prove that he has died a violent death, otherwise he must go back to the upper air and die respectably, i.e. violently.

I have noted the Lethe of the Fiji islands to shew that I am not unaware that savage parallels exist, that a well may be drunk on the 'Path of the Shades' in any land, and that there is no need to suppose that the Greeks borrowed their well either from Fiji or from Egypt; and yet in this particular case it can, I believe, be shewn that the Orphic well came from Egypt, came I believe to Crete, and passed with Orpheus from Crete by the islands to Thrace and to Athens, and thence to Magna Graecia.

Osiris in Egypt had a 'cold' well or water of which he gave the souls to drink. On tombs of Roman date the formulary appears: 'May Osiris give thee the cold water.' Sometimes it is Aidoneus sometimes Osiris who is invoked, for by that time the two were not clearly distinguished. In so far as Osiris was a sun-god the well became a well of light, in which the sun-god Ra was wont to wash his face. In one of the magical papyri the line occurs

'Hail to the water white arid the tree with the leaves high hanging,'

which seems to echo vaguely the white cypress and the forbidden well. The well of Osiris, whatever the precise significance of its Egyptian name, would easily to the Greeks become of double significance and the well would be both cool and fresh and life-giving, by it the soul would revive, it would become 'a living water, springing up into everlasting life.'

A 'living water' given by Osiris to the thirsty soul was part of the eschatology of Egypt, but, so far as we know, Egypt had neither Lethe nor Mnemosyne. In the Book of the Dead there occurs indeed the Chapter of making a man possess memory in the underworld, but the process has no connection with the drinking from a well. The Chapter of drinking water in the underworld is quite distinct. Lethe and Mnemosyne are, I think, Greek developments from the neutral fonds of Egypt, and developments due to the influence of Orpheus.

Lethe as a person is as old as Hesiod. She is bad from the beginning:

'Next hateful Strife gave birth to grievous Toil,

Forgetfulness and Famine, tearful Woes,

Contests and Slaughters.'

By the time of Aristophanes the 'plain of Lethe' is part of the stock furniture of Hades. In the Frogs Charon on the look-out for passengers asks:

'Who's for the plain of Lethe? Who's for the Donkey-shearings?

Who's for the Cerberus folk? or Taenarus? Who's for the Eookeries'

The mystic comic Hades of Aristophanes is thoroughly Orphic. He mentions no well, but he knows of a Stone of Parching', where it may be the thirsty soul sat down to rest.

Lethe as a water, a river, first appears in the Republic of Plato and in such fashion that it seems as though it was by that time proverbial. 'Our story', says Socrates, 'has been saved and has not perished, and it will save us if we are obedient to it, and we shall make a good passage of the river of Lethe and shall not be defiled in our souls.' It is noticeable that to Plato Lethe is of death and pollution. Just before, Socrates has recounted the myth of Er, a myth steeped in Orphic eschatology of metempsychosis and retribution. The souls have been forced to pass each one into the plain of Lethe through scorching suffocating heat, for the plain of Lethe was devoid of trees and of plants that spring from the earth.

Towards evening they took shelter by the river of Unmindfulness whose water no vessel can hold. Of this all were compelled to drink a certain measure, and those who were not safe-guarded by wisdom drank more than the measure, and each one as he drank forgot all things. The river Ameles, Unmindfulness, is of course Lethe: Plato likes to borrow a popular notion and slightly rechristen it. Just so he takes Mnemosyne, Remembrance, and makes of her Anamnesis, Remembering-again. It was not the fashion of his day to give chapter and verse for your borrowings, and Plato so detested the lower side of Orphic rites that perhaps he only half realized the extent of his debts. It is a human and rather malicious touch, that in the order of those who remember again, the man who lives the'initiated life'comes only fifth, side by side with the seer, below the philosopher and the lover and the righteous king and the warrior, below even the economist and the man of business; but after all he cannot much complain, for low though he is, he is above the poet and the artist.

Moreover Plato would take as clearly and vividly known to the initiated all that through lapse of time has become dim to us, and his constant use of the technical terms of initiation is adequate acknowledgement. He tells of the uninitiate, the partly initiate, the newly initiate, wholly initiate, of the man rapt by the divine, whom the vulgar deem distraught, of how before we were caught in the prison of the body we celebrated a most blessed rite, being initiated to behold dimly and see perfectly apparitions complete, simple, quiet and happy, shining in a clear light.

For Mnemosyne and Lethe in Greek religion we are not however dependent on the myths and philosophy of Plato. We have definite evidence in local ritual. Mnemosyne herself takes us straight to the North, the land of Eumolpos and the Muses, to Pangaion, to Pieria, to Helicon. If Orpheus found in Egypt, or as is more probable in Crete, a well of living water, that well was I think nameless, or at least did not bear the name of Mnemosyne. It may of course be accidental, but in the tablet from Crete the well, though obviously the same as that in the Petelia tablet, is unnamed. The name Mnemosyne was found for the well when Orpheus took it with him to the land of the Muses, where he himself got his magic lyre. Not ten miles away from the slopes of Helicon, at the sanctuary of Trophonios at Lebadeia, we find a well not only of Mnemosyne but also of Lethe, and we find the worshipper is made to drink of these wells not in the imagined kingdom of the dead, but in the actual ritual of the living. Man makes the next world in the image of this present.

Pausanias has left us a detailed account of the ritual of the oracle of Trophonios of which only the essential points can be noted here. Before the worshipper can actually descend into the oracular chasm, he must spend some days in a house that is a sanctuary of the Agatho Daimon and of Tyche; then he is purified and eats sacrificial flesh. After omens have been taken and a black ram sacrificed into a trench, the inquirer is washed and anointed and led by the priests to certain'springs of water which are very near to one another, and then he must drink of the water called Forgetfulness, that there may be forgetfulness of everything that he has hitherto had in his mind, and after that he drinks of yet another water called Memory, by which he remembers what he has seen when he goes down below.'He is then shown an image which Daedalus made, i.e. a very ancient xoanon, and one which was only shown to those who are going to visit Trophonios; this he worships and prays to, and then, clad in a linen tunic another Orphic touch and girt with taeniae and shod with boots of the country he goes to the oracle. The ritual that follows is of course a descent into the underworld, the man goes down into the oven-shaped cavity, an elaborate artificial chasm, enters a hole, is dragged through by the feet, swirled away, hears and sees 'the things that are to be', he comes up feet foremost and then the priests set him on the seat, called the seat of Memory, which is near the shrine. They question him and, when they have learnt all they can, give him over to his friends, who carry him possessed by fear and unconscious to the house of Agathe Tyche and Agathos Dairnon where he lodged before. Then he comes to himself and, one is relieved to hear, is able to laugh again. Pausanias says expressly that he had been through the performance himself and is not writing from hearsay.

The Orphic notes in this description are many. To those already discussed we may add that Demeter at Lebadeia was known as Europa, a name which points to Crete. Another Cretan link indicates that the worship of Trophonios was, as we should expect if it is Dionysiac, of orgiastic character. Plutarch, in a passage that has not received the attention it deserves, classes together certain daemons who'do not always stay in the moon, but descend here below to have the supervision of oracular shrines, and they are present at and celebrate the orgies of the most sublime rites. They are punishers of evil deeds and watchers over such.' The word watchers' is the same as that used in the tablet of the guardians of Mnemosyne's well. If in the performance of their office they themselves do wrong either through fear or favour, they themselves suffer for it, and in characteristically Orphic fashion they are thrust down again and tied to human bodies. Then comes this notable statement. 'Those of the age of Kronos said that they themselves were of the better sort of these daemons, and the Idaean Daktyls who were formerly in Crete, and the Korybantes who were in Phrygia, and the Trophoniads in Lebadeia, and thousands of others throughout the world whose titles, sanctuaries and honours remain to this day.' The rites of Daktyls, Kory bants and Trophoniads are all the same and all are orgiastic and of the nature of initiation, all deal with purgation and the emergence of the divine. All have rites that tell of 'things to be' and prepare the soul to meet them.

Pausanias of course understands 'things to be' as merely the future, his attention is fixed on what is merely oracular and prophetic. The action of Lethe is to prepare a blank sheet for the reception of the oracle of Mnemosyne, to make the utterance of the oracle indelible. In point of fact, no doubt, the Trophoniads, the Orphics, found when they came to Lebadeia an ancient hero-oracle. That is clear from the sacrifice of the ram in the trench, a sacrifice made, be it observed, not to Trophonios but to Agamedes, the old hero. That the revelation at Lebadeia of 'things to be' was to the Orphic a vision of and a preparation for the other world is clear from the experiences recounted by Timarchos as having occurred to him in the chasm of Trophonios. Socrates, it is said, was angry that no one told him about it while Timarchos was alive, for he would have liked to hear about it at first hand. What Timarchos saw was a vision of heaven and hell after the fashion of a Platonic myth, and his guide instructed him as to the meaning of things and how the soul shakes off the impurities of the body. The whole ecstatic mystic account beginning with the sensation of a blow on the head and the sense of the soul escaping, reads like a trance experience or like the revelation experienced under an anaesthetic. It may be, and probably is, an invention from beginning to end. The important point is that this vision of things invisible is considered an appropriate experience to a man performing the rites of Trophonios.

The worshipper initiated at Lebadeia drank of Lethe; there was evil still to forget. The Orphic who, after a lite spent in purification, passed into Hades, had done with forgetting; his soul drinks only of Remembrance. It is curious to note that in the contrast between Lethe and Mnemosyne we have what seems to be an Orphic protest against the lower, the sensuous side of the religion of Dionysos. To Mnemosyne, it will be remembered, as to the Muses, the Sun and the Moon and the other primitive potencies affected by the Orphics, the Athenians offered only wineless offerings, but 'ancestral tradition,' Plutarch tells us, 'consecrated to Dionysos, Lethe, together with the narthex.' It is this ancestral tradition that Teiresias remembers when he tells of the blessings brought by the god, and how

'He rests man's spirit dim

From grieving, when the vine exalteth him.

He giveth sleep to sink the fretful day

In cool forgetting. Is there any way

With man's sore heart save only to forget?'

To man entangled in the flesh, man to whom sleep for the body, death for the soul was the only outlook, Lethe became a Queen of the Shades, Assessor of Hades. Orestes, outworn with madness, cries

O magic of sweet sleep, healer of pain,

I need thee and how sweetly art thou come.

O holy Lethe, wise physician thou,

Goddess invoked of miserable men.'

Orpheus found for 'miserable men' another way, not by the vine-god, but through the wineless ecstasy of Mnemosyne. The Orphic hymn to the goddess ends with the prayer

'And in thy mystics waken memory

Of the holy rite, and Lethe drive afar.'

Lethe is to the Orphic as to Hesiod wholly bad, a thing from, which he must purge himself. Plato is thoroughly Orphic when he says in the Phaedrus that the soul sinks to earth 'full of forgetfulness and vice'. The doctrine as to future punishment which Plutarch expounds in his treatise 'On Living Hidden' touches the high water mark of Orphic eschatology. The extreme penalty of the wicked in Erebos is not torture but unconsciousness. Pindar's 'sluggish streams of murky night', he says, receive the guilty, and hide them in unconsciousness and forget fulness. He denies emphatically the orthodox punishments, the gnawing vulture, the wearisome labours; the body cannot suffer torment or bear its marks, for the body is rotted away or consumed by fire;'the one and only instrument of punishment is unconsciousness and obscurity, utter disappearance, carrying a man into the smileless river that flows from Lethe, sinking him into an abyss and yawning gulf, bringing in its train all obscurity and all unconsciousness.'

Lethe and Eunoe in Dante

The Orphic well of Mnemosyne lives on not only in the philosophy of Plato, but also, it would seem, in the inspired vision of Dante. At the close of the Purgatorio, when Dante is wandering through the ancient wood, his steps are stayed by a little stream so pure that it hid nothing, and beside it all other waters seemed to have in them some admixture. The lady gathering flowers on the further bank tells him he is now in the Earthly Paradise: the Highest Good made man good and for goodness and gave him this place as earnest of eternal peace. Man fell away,

'changed to toil and weeping

His honest laughter and sweet mirth.'

Then she tells of the virtue of the little stream. It does not rise, like an earthly water, from a vein restored by evaporation, losing and gaining force in turn, but issues from a fountain sure and safe, ever receiving again by the will of God as much as on two sides it pours forth.

'On this side down it flows and with a virtue

That takes away from man of sin the memory,

On that the memory of good deeds it bringeth.

Lethe its name on this side and Eunoe

On that, nor does it work its work save only

If first on this side then on that thou taste it.'

Dante hears a voice unspeakable say Asperges me, and is bathed in Lethe, and thereafter cannot wholly remember what made him to sin. Beatrice says to him smiling,

'And now bethink thee thou hast drunk of Lethe;

And if from smoke the flame of fire be argued,

This thine oblivion doth conclude most clearly

A fault within thy Will elsewhere intended.'

And she turns to her attendant maid saying,

'See there Eunoe from its source forth flowing.

Lead thou him to it, and as thou art wonted

His virtue partly dead do thou requicken.'

And Dante comes back from 'that most holy wave':

'Refect was I, and as young plants renewing

Their new leaves with new shoots, so I in spirit

Pure, and disposed to mount towards starry heaven.'

The Eunoe of Dante is Good-Consciousness, or the Consciousness of Good. It is the result of a purified, specialized memory, from which evil has fallen away. On the tomb-inscriptions the formulary occurs 'for good thought and remembrance' sake' where the two are very near together. It is just what the Orphic meant by his Remembrance of the Divine, and, when we come to the next tablet, it will seem probable that not only the idea of Good-Consciousness but the very name Eunoia may perhaps have been suggested to Dante by an analogous Orphic well.

THE SYBARIS TABLETS

Six tablets still remain to be considered. Of these five were all found in tombs in the territory of ancient Sybaris, in the modern commune of Corigliano-Calabro. Two of them (III and IV) were found together in a tomb known locally as the Timpone grande. They were folded closely together, and lay near the skull of the skeleton. Their contents, so far as they can be deciphered, are as follows:

III. Timpone grande tablet (a).

'But so soon as the Spirit hath left the light of the sun,

To the right.................... of Ennoia

Then must man............. being right wary in all things.

> Hail, thou who hast suffered the Suffering. This thou hadst never suffered before.

Thou art become God from Man. A kid thou art fallen into milk.

Hail, hail to thee journeying on the right.......

...Holy meadows and groves of Phersephoneia.'

The second line seems to be a fragment of a whole sentence or set of sentences put for the whole, as we might put 'Therefore with Angels and Archangels,' leaving those familiar with our ritual to supply the missing words. Popular quotations and extracts always tend to make the grammar complete or at least intelligible.

The name of the well,'Eimoia,'depends on a conjectural emendation. The tablet of course cannot be the actual source of Dante's Eunoe. It is, however, very unlikely that Dante invented the name; he may have known of Enuoia and modified it to Eunoia. It has been seen that Lethe is regarded as the equivalent of Agnoia, Unconsciousness, and to Aguoia Enuoia would be a fitting contrast.

The formularies that occur at the end, the 'Suffering,' the 'kid' and the 'groves of Phersephoneia' will be considered in relation to other and more complete tablets.

With the'Ennoia'tablet was found

IV. Timpone grande tablet

The inscription on this tablet is unhappily as yet only partially read. It appears to be in some cryptic script.

The broken formularies of tablet (a) and the cryptic script of (b) mark a stage in which the Orphic prescriptions are ceasing to be intelligent and intelligible, and tending to become cabalistic charms. Orphism shared the inevitable tendency of all mystic religions to lapse into mere mechanical magic. In the Cyclops of Euripides, the Satyr chorus, when they want to burn out the eye of the Cyclops, say they know

'A real good incantation

Of Orpheus, that will make the pole go round

Of its own accord.'

Three tablets found near Sybaris yet remain. All these were found in different tombs in the same district as the Timpone grande tablets. In each case the tablet lay near the hand of the skeleton. The tombs were on the estate of Baron Compagno, who presented the tablets to the National Museum at Naples. In form of letters and in content they offer close analogies.

V. Compagno tablet (a).

'Out of the pure I come, Pure Queen of Them Below,

Eukles and Eubouleus and the other Gods immortal.

For I also avow me that I am of your blessed race,

But Fate laid me low and the other Gods immortal

............starflung thunderbolt.

I have flown out of the sorrowful weary Wheel.

I have passed with eager feet to the Circle desired.

I have sunk beneath the bosom of Despoina, Queen of the Underworld.

I have passed with eager feet from the Circle desired.

Happy and Blessed One, thou shalt be God instead of mortal.

A kid I have fallen into milk.'

VI. Compagno tablet (b)

'Out of the pure I come, Pure Queen of the Pure below,

Eukles and Eubouleus and the other Gods and Daemons.

For I also, I avow me, am of your blessed race. I have paid the penalty for deeds unrighteous

Whether Fate laid me low or....

..........with starry thunderbolt.

But now I come a suppliant to holy Phersephoneia

That of her grace she receive me to the seats of the Hallowed.'

VII. Compagno tablet (c).

But for one or two purely verbal differences tablet (c) is precisely the same as (b). It is written carelessly on both sides of the gold plate, and but for the existence of (b) could scarcely have been made out. Tablet (b) has itself so many omissions that its interpretation depends mainly on the more complete contents of (a).

The last tablet to be considered presents two features of special interest. First, the name of its owner Caecilia Secundina 4 is inscribed, and from this fact, together with the loose cursive script in which it is written, the tablet can be securely dated as of Roman times. Second, the contents show but too plainly that the tablet was buried with magical intent.

VIII. Caecilia Secundina tablet.

'She comes from the Pure, Pure Queen of those below

And Eukles and Eubouleus. Child of Zeus, receive here the armour

Of Memory, ('tis a gift songful among men)

Thou Caecilia Secundina, (armour) in due rite to avert evil for ever.'

The tablet reads like a brief compendium from the two sets of formularies already given. We have the statement made to Despoina, Eukles and Eubouleus on behalf of Caecilia that she comes from the congregation of the pure, but it is not followed by the detailed confession of ritual performed that is, so to speak, 'taken as read.' Mention is further made of the divine origin of Caecilia and of Mnemosyne, but in both cases after significant fashion. The 'gift of Mnemosyne' is now not water from a well, but rather the tablet itself, a certificate of Caecilia's purity, in verse, and graven on imperishable gold. Caecilia claims divine descent not from the Orphic Zagreus but from Zeus, who as has already been shown took on, in popular monotheism, something of the nature and functions of Zagreus. Caecilia's theology, like that of the Lower Italy vases, is Orphism made orthodox, Olympicized, conventionalized. The words 'in due rite' seems to imply that the tablet has been 'certified and found correct' by human authority. It is the usual priestly confusion: the soul is divine that no Orphic priest dare deny; and yet this divine soul needs the 'armour' forged by mortal hands. The concluding words aid,'averting evil for ever', make it certain that the intent is magical. The Orphic reverts to the spirit and the vocabulary of the old ritual of 'Aversion.' The armour, is perhaps touched with symbolism like 'the whole armour of God, 'but it is also in part the magic gear of the charlatan. The 'Superstitious Man' of Theophrastus is apt to purify his house frequently, alleging that there has been an induction of Hecate,' Caecilia Secundina brings a tablet engraved with Orphic formularies, and thereby secures means for 'the aversion of evil for ever.'

If the mutilated condition of tablet VII, the illegible character of IV and the express statement of VIII are evidence of the lower, the magical side of Orphism, the complete text of tablets v and vi are the expression of its highest faith, of a faith so high that it may be questioned whether any faith, ancient or modern, has ever out-passed it.

Tablets v and vi both begin with a prayer or rather a claim addressed to the queen of the underworld, later defined as Phersephoneia or Despoina, and to two gods called Eukles and Eubouleus. The two are manifestly different titles of the same divinity. Eukles, 'Glorious One,' is only known to us from a gloss in Hesychius, who defines it as a euphemism for Hades. Eubouleus, 'He of good Counsel,' the local hero and underworld divinity of Eleusis, the equivalent of Plouton, occurs frequently in the Orphic Hymns as an epithet of Dionysos. Eukles and Eubouleus are in fact only titles of the one god of Orphism who appears under many forms, as Hades, Zagreus, Phanes and the like. The gist of this monotheism will fall to be discussed when we come to the theogony of Orpheus. For the present it is sufficient to state that the Eukles-Eubouleus of the tablets, whom the Orphic invokes, is substantially the same as the Zagreus to whom the Cretan Orphic was initiated. To the names named, i.e. the Queen of the Underworld, Eukles and Eubouleus, the Orphic adds 'the other gods and daemons.' This is a somewhat magical touch. The ancient worshipper was apt to end his prayer with some such formulary; it was dangerous to leave any one out. The word, daemons or subordinate spirits, is significant at once of the lower, the magical side of Orphism, and as will be seen later of its higher spirituality. Orphism tended rather to the worship of potencies than of anthropomorphic divinities.

The Orphic then proceeds to state the general basis of his claim: he is of divine birth,

'For I also avow me that I am of your blessed race.'

By this he means, as has been shewn in examining the legend of Zagreus, that some portion of the god Zagreus or Eubouleus or whatever he be called was in him; his fathers the Titans had eaten the god and he sprang from their ashes. That this is the meaning of the tablets is quite clear from the words

'But Fate laid me low...starflung thunderbolt.'

He identifies himself with the whole human race as 'dead in trespasses and sins.' If this were all, his case were hopeless; 'dust we are and unto dust we must return.' He urges at the outset another claim,

The Ritual Formularies

That is, as an Orphic I am purified by the ceremonials of the Orphics. He presents as it were his certificate of spiritual health, he is free from all contagion of evil. 'Bearer is certified pure, coming from a congregation of pure people.' In like fashion in the Egyptian Book of the Dead (No. cxxv.) after the long negative confession made to Osiris the soul says, 'I am pure' 'I am pure,' 'I am pure,' 'I am pure.' He then proceeds to recite his creed, or rather in ancient fashion to confess or acknowledge the ritual acts he has performed. The gist of them each and all is, 'Bad have I fled, better have I found' or as we should put it, 'I have passed from death unto life.' He does not himself say, I am a god that might be overbold but the answer he looks for comes clear and unmistakeable,

'Happy and Blessed One, thou shalt be God instead of mortal.'

The confession he makes of ritual acts is so instructive as to his convictions, so expresses his whole attitude towards religion that it must be examined sentence by sentence.

I say advisedly confession of ritual acts, because each of the little sentences describes in the past tense an action performed, 'I have escaped,' 'I have set my feet' 'I have crept' 'I have fallen.' These several acts described are, I believe, statements of actual ritual performed on earth by the Orphic candidate for initiation, and in the fact that they have been performed lies his certainty of ultimate bliss. They are the exact counterpart of the ancient Eleusinian confession formularies,'I have fasted, I have drunk the kykeon'.

'Out of the pure I come.'

The first article in the creed or confession of the Orphic soul is

'I have flown out of the sorrowful weary Wheel.

The notion of existence as a Wheel, a cycle of life upon life ceaselessly revolving, in which the soul is caught, from the tangle and turmoil of which it seeks and at last finds rest, is familiar to us from the symbolism of Buddha. Herodotus expressly says that the Egyptians were the first to assert that the soul of man was immortal, born and reborn in various incarnations, and this doctrine he adds was borrowed from the Egyptians by the Greeks. To Plato it was already 'an ancient doctrine that the souls of men that come Here are from There and that they go There again and come to birth from the dead'. It was indeed a very ancient saying or doctrine. It has already been observed in discussing the mythology of the Keres and Tritopatores. Orpheus took it as he took so many ancient things that lay to his hand, and moralized it. Rebirth, reincarnation, became for him new birth. The savage logic which said that life could only come from life, that new souls are old souls reborn in endless succession, was transformed by him into a Wheel or cycle of ceaseless purgation. So long as man has not severed completely his brotherhood with plants and animals, not realized the distinctive marks and attributes of his humanity, he will say with Empedocles:

'Once on a time a youth was I, and I was a maiden,

A bush, a bird, and a fish with scales that gleam in the ocean.'

To Plato the belief in the rebirth of old souls was'an ancient doctrine,'but because the Orphics gave it a new mystical content the notion was for the most part fathered on Orpheus or Pythagoras. Diogenes Laertius, who is concerned to glorify Pythagoras, said that he was the first to assert that'the soul went round in a changing Wheel of necessity, being bound down now in this now in that animal.'A people who saw in a chance snake the soul of a hero would have no difficulty in formulating a doctrine of metempsychosis. They need not have borrowed it from Egypt, and yet it is probable that the influence of Egypt, the home of animal worship, helped out the doctrine by emphasizing the sanctity of animal life. The almost ceremonial tenderness shown to animals by the, Pythagorean Orphics is an Egyptian rather than a Greek characteristic. The notion of kinship with the brute creation harmonized well with the somewhat elaborate and self-conscious humility of the Orphic.

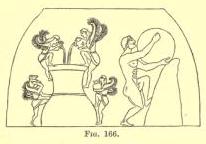

Ritual of the Wheel

What precisely the ritual of the Wheel was we do not know. That there was an actual Wheel in the rites and that some form of symbolical release was enacted is probable. It is indeed almost certain, as we know that Wheels formed part of the sacred furniture of certain sanctuaries. It is worth noting that on Orphic vases of Lower Italy to be discussed later wheels are suspended in the palace of Hades and Persephone, and these are of two kinds, solid and spoked, designed probably for quite different uses. The grammarian Dionysios, surnamed the Thracian, wrote a book on 'The Interpretation of the Symbolism that has to do with Wheels', which probably contained just the necessary missing information. Clement has preserved for us one valuable sentence which makes the ritual use of Wheels a certainty. 'People signify actions', he says, 'not only by words but by symbols, by words as in the case of the Delphic utterances "Nothing too much " and " Know thyself," and in like manner by symbols as in the case of the Wheel that is turned round in the precincts of the gods and that was derived from the Egyptians.' Dionysios is probably right. The Wheel like the Well may have come from Egypt, or from Egyptianized Crete.

Hero of Alexandria in his curious treatise on 'Machines moved by air' twice mentions Wheels as in ritual use.'In Egyptian sanctuaries there are Wheels of bronze against the door-posts, and they are moveable so that those who enter may set them in motion, because of the belief that bronze purifies; and there are vessels for purifying so that those who enter may purify themselves. The problem is how to arrange so that when the Wheel is turned the water may flow mechanically so that as aforesaid it may be sprinkled for purifying.'The problem which Hero faced mechanically the Orphics solved in metaphor how to connect the Wheel with purification. It was not difficult. Bronze, as Hero notes, was supposed to be a purifier; in another section he says the Wheel was actually called Hagnisterion, the thing for purification. Each metal when first it comes into use is regarded as having magical properties. A resonant metal was of special use because it frightened away bogeys. Simaetha in her incantations cries

'The goddess at the Crossways. Sound the gong,'

and the Scholiast on the passage remarks instructively that bronze was sounded at eclipses of the moon, inasmuch as it was held to be pure and to have the power of warding off pollutions, and he quotes the treatise of Apollodorus 'Concerning the Gods' as his authority for the statement that bronze was in use in all kinds of consecration and purification. It was appropriate to the dead, he adds, and at Athens the Hierophant beats a gong when Kore is invoked.

Here again we have a primitive superstition ready to the hand of the Orphic. He is familiar with bronze-beating as a piece of apotropaic ritual; he sees, probably in an Egyptian temple, a bronze wheel known by some name that he translates as'a thing for purifying'; he has a doctrine of metempsychosis and an ardent longing after purification; he puts them all together and says with Proclus the one salvation offered by the creator is that the spirit free itself from the wheel of birth.' This is what those who are initiated by Orpheus to Dionysos and Kore pray that they may attain, to

" Cease from the Wheel and breathe again from ill."

Ritual of the Circle

The notion of escape whether from the tomb of the body, or from the restless Wheel or from the troubled sea, haunts the Orphic, haunts Plato, haunts Euripides, lends him lovely metaphors of a fawn escaped, makes his Bacchants sing,

'Happy he, on the weary sea

Who hath fled the tempest and won the haven.

Happy whoso hath risen free

Above his striving.'

The downward steps from purification to penance, from penance to vindictive punishment, were easy to take and swiftly taken. Plato, in the vision of Er, though he knows of purification, is not free from this dismal and barren eschatology of vengeance and retribution. On Lower Italy vases under Orphic influence, as will later be seen, great Ananke, Necessity herself, is made to hold a scourge and behave like a Fury. That such notions were not alien to Orphism is clear from the line in tablet VI: 'I have paid the penalty for deeds unrighteous.'

The deeds unrighteous are not only the soul's own personal sins but his hereditary taint, the'ancient woe'that is his as the heir of the earth-born Titans.

The next avowal is

'I have passed with eager feet to the Circle desired.'

It occurs in a second form, thus:

I have passed with eager feet from the Circle desired.'

It is impossible to say which form is correct. It may be that both were indispensable, that the neophyte had to pass first into and then out of a, ring or circle.

The words 'I step on or over' is of course frequently used metaphorically with the meaning 'I entered on, embarked on.' It might therefore be possible to translate the words as 'with eager feet I entered on, i.e. I obtained, the crown I longed for.' But as the word crrefyavos means not only a crown for the head, but a ring or circle, a thing that encloses, it is perhaps better to take it here in its wider sense. The mystic has escaped from the Wheel of Purgation, he passes with eager feet over the Ring or circle that includes the bliss he longs for, he enters and perhaps passes out of some sort of sacred enclosure. As to the actual rite performed we are wholly in the dark. Possibly the innermost shrine was garlanded about with mystic magical flowers. This is however pure conjecture. We know that the putting on of garlands or crre/iaro, was the final stage of initiation for Hierophants and other priests, a stage that was as it were Consecration and Ordination in one; but the putting on of garlands is not the entering of a garlanded enclosure, and it is the entering of an enclosure that the'eager feet'seem to imply.

Next comes the clause,

I have sunk beneath the bosom of Despoina, Queen of the Underworld.'

That this clause is an avowal of an actual rite performed admits of no doubt. It is the counterpart of the 'token' of the mysteries of the Mother: 'I have passed down into the bridal-chamber' but here the symbolism seems to be rather of birth than marriage. In discussing the ritual of the Semnae, it has been seen that the 'second-fated man' had to be reborn before he could be admitted to the sanctuary, and the rebirth was a mimetic birth. The same ceremony was gone through among some peoples at adoption. Dionysos himself in Orphic hymns is called 'he who is beneath the bosom.' If the rites are enumerated in the order of their performance this rite of birth or adoption must have taken place within the Circle, after the entrance into and before the exit from.

In the highest grades of initiation not only was there a new birth but also a new name given, a beautiful custom still preserved in the Roman Church. Lucian 4 makes Lexiphanes tell of a man called Deinias, who was charged with the crime of having addressed the Hierophant and the Dadouchos by name,'and that when he well knew that from the time they are consecrated they are nameless and can no longer be named, on the supposition that they have from that time holy names.'

The last affirmation of the mystic is

'A kid I have fallen into milk,'

a sentence which occurred, it will be remembered, in the second person, on tablet III.

The quaint little formulary is simple almost to fatuity. Mysticism, in its attempt to utter the ineffable, often verges on imbecility.

Before we attempt to determine the precise nature of the ritual act performed, it may be well to consider the symbolism of the kid and the milk. It is significant that in both cases the formulary occurs immediately after another statement:

'Thou shalt be God instead of mortal.'

The Kid and the Milk

It would seem that about the kid there is something divine. Eriphos according to Hesychius was a title of Dionysos. Stephanas the Byzantine says that Dionysos bore the title Eriphios among the Metapontians, i.e. in the very neighbourhood where these Orphic tablets were engraved. It is clear that there was not only a Bull-Dionysos (Eiraphiotes) but a Kid-Dionysos (Eriphos), and this was just the sort of title that the Orphics would be likely to seize on and mysticize. In the Bacchae it has been seen that there seems to attach a sort of special sanctity to young wild things, a certain mystic symbolism about the fawn escaped, and the nursing mothers who suckle the young of wolves and deer. It may be that each one thought her nursling was a Baby-God. Christian children to this day are called Christ's Lambs because Christ is the Lamb of God, and Clement joining new and old together says: 'This is the mountain beloved of God, not the place of tragedies like Cithaeron but consecrated to the dramas of truth, a mount of sobriety shaded with the woods of purity. And there revel on it not the Maenads, sisters of Semele the thunderstruck, initiated in the impure feast of flesh, but the daughters of God, fair Lambs who celebrate the holy rites of the Word, raising a sober choral chant'.

The initiated then believed himself new born as a young divine animal, as a kid, one of the god's many incarnations; and as a kid he falls into milk. Milk was a god-given drink before the coming of wine, and the Epiphany of Dionysos was shown not only by wine but by milk and honey:

'Then streams the earth with milk, yea streams

With wine and honey of the bee.'

Out on the mountain of Cithaeron he gives his Maenads draughts of miraculous wine, and also

'If any lips

Sought whiter draughts, with dipping finger-tips

They pressed the sod, and gushing from the ground

Came springs of milk. And reed-wands ivy-crowned

Ean with sweet honey.'

The symbolism of honey, the nectar of gods and men, does not here concern us, but it is curious to note how honey, used in ancient days to embalm the dead body, became the symbol of eternal bliss. A sepulchral inscription of the first century A.D. runs as follows:

'Here lies Boethos Muse-bedewed, undying

Joy hath he of sweet sleep in honey lying.'

Boethos lies in honey, the mystic falls into milk, both are symbols taken from the ancient ritual of the Nephalia and mysticized.

The question remains what was the exact ritual of the falling into milk? The ritual formulary is not 'I drank milk' but 'I fell into milk'. Did the neophyte actually fall into a bath of milk, or, as in the case of 'I stepped on the crown I longed for', is the ritual act of drinking milk from the beginning metaphorically described? The question unhappily cannot with certainty be decided. The words'I fell into milk' are not even exactly what we should expect if a rite of Baptism were described; of a rite of immersion in milk we have no evidence.

Primitive Baptism

It is however from primitive rites of Baptism that we get most light as to the general symbolism of the formulary. In the primitive Church the sacrament of Baptism was immediately followed by Communion. The custom is still preserved among the Copts. The neophyte drank not only of Wine but also of a cup of Milk and Honey mixed, those 'new born in Christ' partook of the food of babes. Our Church has severed Communion from Baptism and lost the symbolism of Milk and Honey, nor does she any longer crown her neophytes after Baptism.

S. Jerome complains in Protestant fashion that much was done in the Church of his days from tradition that had not really the sanction of Holy Writ. This tradition which the early Church so wisely and beautifully followed can only have come from pagan sources. Among the unsanctioned rites S. Jerome mentions the cup of Milk and Honey. That the cup of Milk and Honey was pagan we know from a beautiful prescription preserved in one of the Magic Papyri in which the worshipper is thus instructed: 'Take the honey with the milk, drink of it before the rising of the sun, and there shall be in thy heart something that is divine.'

The milk and honey can be materialized into a future'happy land'flowing with milk and honey, but the promise of the magical papyrus is the utmost possible guerdon of present spiritual certainty. We find in every sacrament what we bring.

If the formularies inscribed on the tablets have been actually recited while the Orphic was alive we naturally ask When and at what particular Mysteries? To this question no certain answer can be returned. Save for one instance,

I have sunk beneath the bosom of Despoina, Queen of the Underworld,

the formularies of the tablets bear no analogy either to the tokens of Eleusis or to those of the Great Mother. The Greater Mysteries at Eleusis were preceded, we know, by Lesser Mysteries celebrated at Agra, a suburb of Athens. These mysteries were sacred to Dionysos and Kore rather than to Demeter, and it is noticeable that in the tablets there is no mention of Demeter, no trace of agricultural intent; the whole gist is eschatological. But, found as they are in Crete and Lower Italy, it is more probable that these tablets refer to Orphic mysteries pure and simple before Orphic rites have blended with those of the Wine-God. Pythagoras, tradition says, was initiated in Crete; he met there 'one of the Idaean Daktyls and at their hands was purified by a thunderbolt; he lay from dawn outstretched face-foremost by the sea and by night lay near a river covered with fillets from the fleece of a black lamb, and he went down into the Idaean cave holding black wool and spent there the accustomed thrice nine hallowed days and beheld the seat bedecked every year for Zeus, and he engraved an inscription about the tomb with the title "Pythagoras to Zeus" of which the beginning is:

"Here in death lies Zan, whom they call Zeus,"

and after his stay in Crete he went to Italy and settled in Croton.'

The story looks as if Pythagoras had brought to Italy from Crete Orphic rites in all their primitive freshness. The religion of Dionysos was not the only faith that taught man he could become a god. The dead Egyptian also believed that he could become Osiris. The Orphic in Crete and Lower Italy may have had rites dealing with his conduct in the next world more directly than those of the Great Mother or of Eleusis.

This is made the more probable from the fact that we certainly know that the sect of the Pythagoreans had special burial rites, strictly confined to the Initiated. Of this Plutarch incidentally gives clear evidence in his discourse of 'The Daemon of Socrates.' A young Pythagorean, Lysis, came to Thebes and died there and was buried by his Theban friends. His ghost appeared in a dream to the Pythagorean friends he had left in Italy. The Pythagoreans, more skilled in these matters than modern psychical experts, had a certain sign by which they knew the apparition of a dead man from the phantasm of the living. They got anxious as to how Lysis had been buried, for'there is something special and sacrosanct that takes place at the burial of the Pythagoreans and is peculiar to them, and if they do not attain this rite they think that they will fail in reaching the very happy end that is proper to them.' So concerned were some of the Pythagoreans that they wished to have the body of Lysis disinterred and brought to Italy to be reburied. Accordingly one of them, Theanor, started for Thebes to make enquiries as to what had been done. He was directed by the people of the place to the tomb and went in the evening to offer libations, and he invoked the soul of Lysis to give inspired direction as to what was to be done. 'As the night went on,' Theanor recounts, 'I saw nothing, but I thought I heard a voice say " Move not that which should not be moved," for the body of Lysis was buried by his friends with sacrosanct ceremonies, and his spirit is already separated from it and set free into another birth, having obtained a share in another spirit.'On enquiry next morning Theanor found that Lysis had imparted to a friend all the secret of the mysteries so that the funeral rites had been performed after Pythagorean fashion.

What precisely the sacrosanct rites were we cannot in detail say, but we may be tolerably sure that something special was done for the man who had been finally initiated, who was like the Cretan mystic, 'consecrated.' This something may have included the burial with his body of tablets inscribed with sentences from his 'Book of the Dead'. This I think is implied in a familiar passage of Plato. Socrates in the Phaedo says that 'the journey to Hades does not seem to him a simple road like that described by Aeschylus in the Telephos. On the contrary it is neither simple nor one. If it were there would be no need of guides. But it appears in point of fact to have many partings of the ways and circuits. And this,' he adds, 'I say conjecturing it from the customary and sacrosanct rites which we observe in this world.' The customary rites were for each and all; the sacrosanct rites were for the initiated only, for they only were sacrosanct.

The Pythagoreans we know revived the custom of burial in the earth, which had been at least in part superseded by the Northern practice of cremation. It was part of their general return to things primitive. Earth was the kingdom of 'Despoina, Queen of the underworld,' who was more to them than Zeus of the upper air. To their minds bent on symbolism burial itself would be a consecration, they would remember that to the Athenians the dead were Demeter's people, that burial was refused to the traitor because he was unworthy 'to be consecrated by earth 'and burial in itself may well have been to them as to Antigone a mystic marriage:

I have sunk beneath the bosom of Despoina, Queen of the Underworld.'

Orphic Vases Of Lower Italy

Orphic religion, as seen on the tablets just discussed, is singularly free from 'other-worldliness.' It is a religion promising, indeed, immortality, but instinct not so much with the hope of future rewards as with the ardent longing after perfect purity; it is concerned with the state of a soul rather than with its circumstances. We have the certainty of beatitude for the initiated, the 'seats of the blessed', the 'groves of Phersephoneia,' but the longing uttered is ecstatic, mystic not sensuous; it is summed up in the line:

'Happy and Blessed One, thou shalt be God instead of mortal.'

None knew better than the Orphic himself that this was only for the few:'Many are they that carry the narthex, few are they that are made one with Bacchus.'For the many there remained other and lower beatitudes, there remained also a thing wholly absent from the esoteric Orphic doctrine the fear of punishment, punishment conceived not as a welcome purification, but as a fruitless, endless vengeance. Of the existence of this lower faith or rather unfaith in the popular forms of Orphism we have definite and curious evidence from a class of vases, found in Lower Italy, representing scenes in the underworld and obviously designed under Orphic influence.

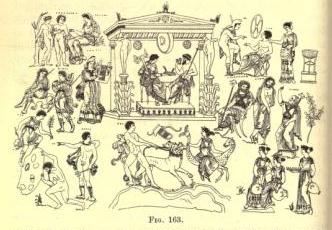

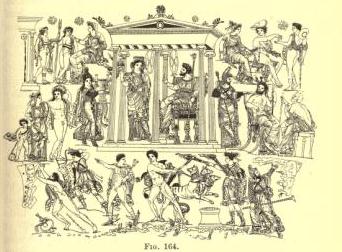

Two specimens of

these'Apulian'vases are given in figs. 163 and 164.

Two specimens of

these'Apulian'vases are given in figs. 163 and 164.

It will be obvious at the first glance that the composition of both designs is substantially the same. This need not oblige us to conjecture any one great work of art of which these two and the other designs not figured here are copies; it only shows that some vase-painter of note in the 4th century B.C. conceived the scheme and it became popular in his factory.

The main lines of both compositions are as follows: in the centre the palace of Hades with Plouton and Persephone. Immediately below, and also occupying a central position, is Herakles, carrying off Cerberus. Immediately to the left of the temple. and therefore also fairly central, is the figure of Orpheus. About these central figures various groups of criminals and other denizens of Hades are diversely arrayed.

With this scheme in our minds we

may examine the first specimen, the most important of the series,

because inscribed. The vase itself, now in the Naples Museum and

usually known from the place where it was found as the 'Altamura'

vase, is in a disastrous condition. It was put together out of

hundreds of fragments, painted over and freely restored after the

fashion of the day, and it has never yet been subjected to a

proper chemical cleaning. Much therefore in the drawing remains

uncertain, and only such parts and inscriptions will be dealt

with as are above suspicion.

With this scheme in our minds we

may examine the first specimen, the most important of the series,

because inscribed. The vase itself, now in the Naples Museum and

usually known from the place where it was found as the 'Altamura'

vase, is in a disastrous condition. It was put together out of

hundreds of fragments, painted over and freely restored after the

fashion of the day, and it has never yet been subjected to a

proper chemical cleaning. Much therefore in the drawing remains

uncertain, and only such parts and inscriptions will be dealt

with as are above suspicion.

The palace of Hades, save for the suspended wheels, presents no features of interest. In the'Altamura'vase many of its architectural features are from the hand of the restorer, but from the other vases the main outlines are sure. In the Altamura vase both Hades and Persephone are seated in the others sometimes Persephone, sometimes Plouton occupies the throne. Had the designs been exclusively inspired by Orphic tradition, more uniform stress would probably have been laid on Persephone.

The figure of Orpheus, common to both vases, is interesting from its dress, which reminds us of Vergil's description,

'There too the Thracian priest in trailing robe

The vase-painter of the late 4th cent. B.C. was more archaeologist than patriot. In the Lesche picture of Polygnotus, Pausanias expressly notes that Orpheus was'Greek in appearance,'and that neither his dress nor the covering he had on his head was Thracian. The Orpheus of Polygnotus must have been near akin to the beautiful Orpheus of the vase-painter in fig. 142. Polygnotus, too, made him'seated as it were on a sort of hill, and grasping his cithara with his left hand; with the other he was touching some sprays of willow, and he leant against a tree.' Very different this from the frigid ritual priest.

Orpheus in Hades

About this figure of Orpheus an amazing amount of nonsense has been written. The modern commentator thinks of Orpheus as two things as magical musician, which he was, as passionate lover, which in early days he was not. The commentator's mind is obsessed by 'Che faro senza te, Eurydice?' He asks himself the question, 'Why has Orpheus descended into Hades?' and the answer rises automatically, 'To fetch Eurydice.' As regards these Lower Italy vases there is one trifling objection to this interpretation, and that is that there is no Eurydice. Tantalos, Sisyphos, Danaides, Herakles, but no Eurydice. This does not deter the commentator. The figure of Eurydice is 'inferred rather than expressed. 'Happily this line of interpretation, which might lead us far, has been put an end to by the discovery of a vase in which Eurydice does appear; Orpheus leads her by the wrist and a love-god floats above. It is evident that when the vase-painter wishes to'express 'Eurydice he does not leave her to be'inferred.'

It may be taken as an axiom in Greek mythology that passionate lovers are always late. The myth of Eurydice is of considerable interest, but not as a love-story. It is a piece of theology taken over from Dionysos, and, primarily, has nothing to do with Orpheus. Anyone who realizes Orpheus at all would feel that the intrusion of desperate emotion puts him out of key. Semele, the green earth, comes up from below, year by year; with her comes her son Dionysos, and by a certain instinct of chivalry men said he had gone to fetch her. The mantle of Dionysos descends on Orpheus.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Eurydice is one of those general, adjectival names that are appropriate to any and every goddess: she is the 'Wide-Ruler.' At Trozen, Pausanias saw 'a Temple of Artemis the Saviour, and in it were altars of those gods who are said to rule below the earth, and they say that in this place Semele was brought up from Hades by Dionysos, and that here Herakles dragged up the hound of Hades.' Pausanias is sceptical: 'But I do not the least believe that Semele died, she who was the wife of Zeus, and as to the beast called the hound of Hades, I shall state what I am sure is the truth about him in another place.' The cult of Artemis is clearly superposed over an ancient, perhaps nameless, anyhow forgotten cult of underworld gods. There was probably a cleft at hand and a legend of a rising Earth -goddess, as at the rock of Recall, Anaklethrar, and the Smileless Rock at Eleusis; and of course, given somebody's Anodos, a Kathodos is soon supplied, and then a formal descent into Hades. At the Alcyonian lake, near Argos, which Nero tried in vain to sound, the Argives told Pausanias that Dionysos went down to Hades to fetch Semele, and Polymnos, a local hero, showed him the way down, and'there were certain rites performed there yearly.'Unfortunately, as is mostly the case when he comes to the real point, Pausanias found it would 'not be pious' to reveal these rites to the general public. At Delphi, too, it will be remembered the Thyiades knew the mystic meaning of the festival of Herois, and 'even an outsider could conjecture'. Plutarch says, from what was done, that it was an upbringing of Semele.

Orpheus, priest of Dionysos, took on his resurrection as well as his death; that is the germ from which sprang the beautiful love-story. A taboo-element, common to many primitive stories, is easily added. You may not look back when spirits are about from the underworld. If you do you may have to join them. Underworld rites are often performed 'without looking back'.

There is another current fallacy about these underworld vases. Commentators are not only prone to the romantic tendency to see a love-story where none is, but, having once got the magical musician into their minds, they see him everywhere. In these vases, they say, we have'the power of music to stay the torments of hell.'They remember, and small wonder, the amazing scene in Gluck's opera, where Orpheus comes down into the shades playing on his lyre, and the clamour of hell is spell-bound; or they bethink them of Vergil:

'The very house itself, the inmost depths

Of Death stood still to hearken.'

But the vase-painter of the 4th cent. B.C. is necessarily guiltless of Vergil as of Gluck. Moreover his work is untinged by any emotion, whether of poetry or religion; his composit an omnium gatherum of conventional orthodox Orpheus is there because, by that time, convention demanded his presence. The vase-painter's wealthy clients these Apulian vases were as expensive as they are ugly would have been ill-pleased had the founder of popular mysteries not had his fitting place. But if interest focusses anywhere in a design so scattered and devitalized, it is on the obvious 'record' of Herakles, who, tradition said, had been initiated, not on the secret magic of Orpheus. It is true that the Danaides, when they appear, are doing nothing but dangling their pitchers in attitudes meant to be decorative, but Tantalos still extends a hand to keep off his rock, and Sisyphos still uprolls the 'pitiless' stone; there is no pause in their torments.

It remains to note the figures in the side groups. In the top row to the left are Megara and her sons, placed there by a pardonable anachronism, out of compliment to Herakles and Athens. We should never have guessed their names, but the inscriptions are certain. Opposite them to the right a group which on the Altamura vase is almost certainly due to restoration. The figures are Myrtilos, Pelops, and Hippodameia. To the left of Orpheus are two Poinae, developments, as has been seen, of the tragic Erinyes. Above Sisyphos is another figure, a favourite of the Orphics, Ananke, Necessity. Only three letters of the name remain, but the restoration is practically certain. Opposite Orpheus are the three 'Judges' of Hades, Triptolemos, Aiakos, Rhadamanthys. Below the Judges are women bearing water-vessels, to whom provisionally we may give the canonical name of 'Danaides.' The sea horse is probably due to the restorer.

Turning to the Canosa vase, now in the Old Pinakothek at Munich, we find that, though none of the figures are inscribed, most can easily be traced. Some modifications of the previous scheme must be noted. Tantalos the Phrygian takes the place of the Danaides. Near Orpheus, in place of the Poinae, is a group, man, wife and child, who are hard to interpret. No mythological figures quite suit them, and some authorities incline to see in the group just a human family initiated by Orpheus in his rites. In face of the fact that all the other figures present are mythological, this is, I think, difficult to accept. The figures are best left unnamed till further evidence comes to light. On the right hand, in the top row, is a group of great interest, Theseus, Peirithoos and Dike, armed with a sword.

To resume, we have as certain elements in these vases Orphgus, the three Judges of Hades, two heroes, Herakles and Theseus, who go down into Hades and return thence, two standard Homeric criminals, Sisyphos and Tantalos, and, in the case of the Altamura vase, the Danaides. The question naturally rises, is there in all these figures any common factor which determines their selection, or is it a mere haphazard aggregate?

The answer is as simple as instructive, and may be stated at the outset: All the canonical denizens of the underworld are hero and heroine figures of the older stratum of the population. Hades has become a sort of decent Dower-house to which are relegated the divinities of extinct or dying cults.

In discussing hero-worship, we have already seen that Tityos and Salmoneus are beings of this order. Once locally the rivals of Zeus, they paled before him, and as vanquished rivals became typical aggressors, punished for ever as a warning to the faithful. Tityos does not appear on Lower Italy vases, but Pausanias saw him on the fresco of Polygnotus at Delphi, a 'dim and mangled spectre', and Aeneas in the underworld says:

'I saw Salmoneus cruel payment make,

For that he mocked the lightning and the thunder

Of Jove on high.'

It was an ingenious theological device, or rather perhaps unconscious instinct, that took these ancient hero figures, really regnant in the world below, and made the place of their rule the symbol of their punishment. According to the old faith all men, good and bad, went below the earth, great local heroes reigned below as they had reigned above; but the new faith sent its saints to a remote Elysium or to the upper air and made this underworld kingdom a place of punishment; and in that place significantly we find that the tortured criminals are all offenders against Olympian Zeus.

We must confine our examination to the two typical instances selected by the vase-painter, Sisyphos and Tantalos.

We are apt to think of Sisyphos and Tantalos as punished for overweening pride and insolence, and to regard their downfall as a warning of the ephemeral nature of earthly prosperity.

'Oh what are wealth and power! Tantalus

And Sisyphus were kings long years ago,

And now they lie in the lake dolorous;

The hills of hell are noisy with their woe,

Aye swift the tides of empire ebb and flow.'

Kings they were, but kings of the old discredited order. Homer says nothing of their crime, he takes it as known; but in dim local legends we can in both cases track out the real gist of their ill-doing: they were rebels against Zeus.

This is fairly clear in the case of Tantalos. According to one legend he suffered because he either stole or concealed for Pandareos the golden hound of Zeus. According to the epic author of the 'Return of the Atreidae,' he had been admitted to feast with the gods, and Zeus promised to grant him whatever boon he desired.'He', Athenaeus says, 'being a man insatiable in his desire for enjoyment, asked that he might have eternal remembrance of his joys and live after the same fashion as the gods.' Zeus was angry; he kept his promise, but added the torment of the imminent stone. It is clear that in some fashion Tantalos, the old hero-king, tried to make himself the egual of the new Olympians. The insatiable lust is added as a later justification of the vengeance. Tantalos is a real king, with a real grave. Pausanias says,'In my country there are still signs left that Pelops and Tantalos once dwelt there. There is a famous grave of Tantalos, and there is a lake called by his name. The grave, he says elsewhere, he had himself seen in Mount Sipylos, and 'well worth seeing it was.' He mentions no cult, but a grave so noteworthy would not be left untended.

The legend of Sisyphos, if more obscure than that of Tantalos, is not less instructive. The Iliad knows of Sisyphos as an ancient king. When Glaukos would tell his lineage to Diomede he says:

'A city Ephyre there was in Argos'midmost glen

Horse-rearing, there dwelt Sisyphos the craftiest of all men,

Sisyphos son of Aiolos, and Glaukos was his son,

And Glaukos had for offspring blameless Bellerophon.'

Ephyre is the ancient name of Corinth, and on Corinth Pausanias in his discussion of the district has a highly significant note. He says, 'I do not know that anyone save the majority of the Corinthians themselves has ever seriously asserted that Corinthos was the son of Zeus.' He goes on to say that according to Eumelus (circ. B.C. 750), the 'first inhabitant of the land was Ephyra, daughter of Okeanos.' The meaning is transparent. An ancient pre-Achaean city, with an eponymous hero, a later attempt discredited of all but the interested inhabitants to affiliate the indigenous stock to the immigrant conquerors by a new eponymous hero, a son of Zeus.

Sisyphos

The epithet 'craftiest' is, as Eustathius observes, a 'mid-way expression,' i.e. for better for worse. 'Glaukos,' he says in his observant way, 'does not wish to speak evil of his ancestor.' The word he uses means very clever, very ready and versatile. It is in fact no more an epithet of blame than 'of many wiles' the stock epithet of Odysseus. Eustathius goes on to explain the meaning of the name Sisyphos. Sisyphos, he says, was among the ancients a word of the same significance as divinely wise. He cites the oath used by comic poets, 'by the gods'. Whether Eustathius is right, and Sisyphos means 'divinely wise' or whether we adopt the current, etymology and make Sisyphos a reduplicated form of the 'Very Very Wise One,,' thus much is clear. The title was traditionally understood as of praise rather than blame, and it is not rash to see in it one of the cultus epithets of the old religion like 'The Blameless One.'

It is as a benefactor that Sisyphos appears in local legend. It was Sisyphos, Pausanias says, who found the child Melicertes, buried him, and instituted in his honour the Isthmian games. It was to Sisyphos that Asopos gave the fountain behind the temple of Aphrodite, and for a reason most significant. 'Sisyphos', the story says, 'knew that it was Zeus who had carried off Aegina, the daughter of Asopos, but he would not tell till the spring on Acrocorinthus was given him. Asopos gave it him, and then he gave information, and for that information he, if you like to believe it, paid the penalty in Hades'. Pausanias is manifestly sceptical, but his story touches the real truth. Sisyphos is the ally of the indigenous river Asopos. Zeus carries off the daughter of the neighbouring land; Sisyphos, hostile to the conqueror, gave information, and for that hostility he suffers in Hades. But though he points a moral in Olympian eschatology, he remains a great local power. The stronghold of the lower city bore his name, the Sisypheion. Diodorus relates how it was besieged by Demetrius, and when it was taken the garrison surrendered. It must have been a place of the old type, half fortress half sanctuary. Strabo notes that in his day extensive ruins of white marble remained, and he is in doubt whether to call it temple or palace.

As to the particular punishment selected for Sisyphos, a word remains to be said. It bears no relation to his supposed offence, whether that offence be the cheating of Death or the betrayal of Zeus. His doom is ceaselessly to upheave a stone. Keluctant fir though I am to resort to sun-myths, it seems that here the sun counts for something. The sun was regarded by the sceptical as a large red-hot stone: its rising and setting might very fitly be represented as the heaving of such a stone up the steep of heaven, whence it eternally rolls back. The worship of Helios was established at Corinth; whether it was due to Oriental immigration or to some pre-Hellenic stratum of population cannot here be determined. Sisyphos was a real king, the place of his sepulture on the Isthmus was known only to a few. It may have been kept secret like that of Neleus for prophylactic purposes. But a real king may and often does take on some of the features and functions of a nature god.

On the 'Canosa'vase, immediately above Tantalos, is a group of three Judges, carrying sceptres. On the Altamura vase are also three Judges, occupying the same place in the composition, and happily they are inscribed Triptolemos, Aiakos, and Rhadamanthys. Two of the three, Triptolemos and Aiakos, certainly belong to the earlier stratum.

Triptolemos had never even the shadowiest connection with any Olympian system; there is no attempt to affiliate him; he ends as he began, the foster-child of Demeter and Kore, and by virtue of his connection with the 'Two Goddesses' of the underworld he reigns below. Demeter and Kore, the ancient Mother and Maid, were strong enough to withstand, nay to out-top, any number of Olympian divinities. To tamper with the genealogy of their local hero was felt to be useless andnever attempted.

The Judges of Hades

In striking contrast to Triptolemos, Aiakos seems at first sight entirely of the later stratum. He is father of the great Homeric heroes, Telamon and Peleus, and when a drought afflicts Greece it is he who by sacrifice and prayer to Pan-Hellenian Zeus procures the needful rain. Recent investigation has, however, clearly shown that Aiakos is but one of the countless heroes taken over, affiliated by the new religion, and his cult, though overshadowed, was never quite extinguished. One fact alone suffices to prove this. Pausanias saw and described a sanctuary in Aegina known as the Aiakeion. 'It stood in the most conspicuous part of the city, and consisted of a quadrangular precinct of white marble. Within the precinct grew ancient olives, and there was there also an altar rising only a little way from the ground, and it was said, as a secret not to be divulged, that this altar was the tomb of Aiakos'. The altar-tomb was probably of the form already discussed and seen in fig. 9. Such a tomb, as altar, presupposes the cult of a hero.

Minos does not appear on these Lower Italy vases. In his place is Rhadamanthys, his brother and like him a Cretan. The reason of the substitution is perhaps not far to seek. Eustathius notes that some authorities held that Minos was a pirate and others that he was just and a lawgiver. It is not hard to see to which school of thinkers the Athenians would be apt to belong, and the Lower Italy vases are manifestly under Attic influence. If the old Cretan tradition had to be embodied, Rhadamanthys was a safe non-committal figure. He is most at home in the Elysian fields, a conception that was foreign to the old order. As brother of Minos, Rhadamanthys must have belonged to the old Pelasgian dark-haired stock, but we find with some surprise that he is in the Odyssey 'golden -haired', like any other Achaean. Eustathius hits the mark when he says, 'Rhadamanthys is golden-haired, out of compliment to Menelaos, for Menelaos had golden hair.

Herakles and Theseus remain, and need not long detain us.

Herakles is obviously no permanent denizen of Hades; he is triumphant, not tortured; he hales Cerberus to the upper air, and that there may be no mistake Hermes points the way. It has already been seen that Herakles was a hero, the hero well worth Olympianizing though he never became quite Olympianized. In the Nekuia, when the poet is describing Herakles, he is caught on the horns of a dilemma between the old and the new faith, and instinctively he betrays his predicament. Odysseus says:

'Next Herakles'great strength I looked upon,

His shadow, for the man himself is gone

To join him with the gods immortal; there

He feasts and hath for bride Hebe the fair.'

The case of Theseus is different. In the Hades of Vergil he is a criminal condemned for ever:

'There sits, and to eternity shall sit,

Unhappy Theseus.'

But on these Lower Italy vases we have again to reckon with Athenian influence. Theseus is of the old order, son of Poseidon, but Athens was never fully Olympianized, and she will not have her hero in disgrace. Had he not a sanctuary at Athens, an ancient asylum? Were not his bones brought in solemn pomp from Skyros? So the matter is adjusted with considerable tact. Theseus, never accounted as guilty as Peirit hob's, is suffered to return to the upper air, Peirithoos has to remain below; and this satisfies Justice, Dike, the woman seated by his side. That the woman holding the sword is none other than Dike herself is happily certain, for she appears inscribed on the fragment of another and similar amphora in the Museum at Carlsruhe. Near her on this fragment is Peirithoos, also inscribed.

Dike in Hades