|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER XII.

ORPHIC COSMOGONY

The World-Egg | The Egg in Orphic Ritual | Eros as Herm | Eros As Ker Of Life | Eros as Ephebos | Eros And The Mother | Aphrodite of the Mysteries | Mysteries at Phlya | Pythagorean Revivals | The Orphic Pan | The Mystic Dionysos |

IF, in attempting to understand Orphic Theogony, we turn to the collection of hymns known as 'Orphic,' hymns dating for the most part about the 4th century A.D., we find ourselves at once in an atmosphere of mystical monotheism. We have addresses to the various Olympians, to Zeus and Apollo and Hera and Athene and the rest, but these are no longer the old, clear-cut, departmental deities, with attributes sharply distinguished and incommunicable; the outlines are all blurred; we feel that everyone is changing into everyone else. A few traditional epithets indeed remain; Poseidon is still 'dark-haired,' and 'Lord of Horses' he is a stubborn old god and hard to fuse; but, for the most part, sooner or later, all divinities greater or less, mingle in the mystery melting-pot, all become 'multiform,' 'mighty' 'all-nourishing,' 'first-born' 'saviours' 'all-glorious' and the like. In a word the several gods by this time are all really one, and this one god is mystically conceived as a potency rather than a personal divinity.

The doctrine of the mutation of the gods, now into one shape, now into another, was, it would seem, part of the regular symbolic teaching of the mysteries. It is easy to see that such a doctrine would lend itself readily to the notion of their interchangeability. Proclus says:'In all the rites of initiation and mysteries the gods exhibit their shapes as many, and they appear changing often from one form to another, and now they are made manifest in the emission of formless light, now taking human shape, now again in other and different form.'

By the date of the 'Hymns' monotheism was of course in some degree the common property of all educated minds, and cannot therefore be claimed as distinctive of Orphism. Wholly Orphic, however, is the mystical joy with which the Hymns brim over; they are'full of repetitions and magniloquence, and make for emotion. 'They are like learned, self-conscious, even pretentious echoes of the simple ecstasy of the tablets.

It would therefore be idle to examine the Orphic Hymns severally and in detail, in order to extract from them the Orphic characteristics of each particular god. Any one who reads them through will speedily be conscious that, save for the procemium, and an occasional stereotyped epithet, it would usually be impossible to determine which hymn was addressed to what god. With whatever attempt at individualization they begin, the poet is soon safe away into a mystical monotheism. A more profitable enquiry is, how far did primitive Orphism attempt monotheism, and of what nature was the one God whom the Orphic made in his own image? Here, fortunately, we are not left wholly without evidence.

The World-Egg

In the Birds of Aristophanes, the chorus tells of a time, when Earth and Air and Heaven as yet were not, only Chaos was, and Night and black Erebos:

'In the beginning of Things, black-winged Night

Into the bosom of Erebos dark and deep

Laid a wind-born egg, and, as the seasons rolled,

Forth sprang Love7%leaming with wings of gold,

Like to the whirlings of wind, Love the Delight

And Love with Chaos in Tartaros laid him to sleep;

And we, his children, nestled, fluttering there,

Till he led us forth to the light of the upper air.'

This is pure Orphism. Homer knows of no world-egg, no birth of Love. Homer is so dazzled by the splendour of his human heroes and their radiant reflections in Olympus that his eyes never look back to see from whence they sprang. He cares as little, it seems, for the Before as for the Hereafter. The two indeed seem strangely linked together. An eschatology and a cosmogony are both pathetic attempts to answer the question Homer never cared to raise, Whence came Man and the Good and Evil of humanity?

We have of course a cosmogony in Hesiod, Hesiod who is a peasant and a rebel, a man bitter and weary with the hardness of life, compelled by rude circumstances to ask why things are so evil, and always ready, as in the myth of Pandora, to frame or borrow a crude superstitious hypothesis. How much Hesiod borrowed from Orphism is hard to say. He knows of Night and Chaos and the birth of Eros, but he does not know, or does not care to tell, of one characteristic Orphic element, the cosmic egg. He only says:

'First Chaos came to be and Gaia next

Broad-bosomed, she that was the steadfast base

Of all things Ge, and murky Tartaros

Deep in the hollow of wide earth. And next

Eros, most beautiful of deathless gods

Looser of limbs, Tamer of heart and will

To mortals and immortals.'

Hesiod is not wholly Orphic, he is concerned to hurry his Eros up into Olympus, one and most beautiful among many, but not for Hesiod the real source of life, the only God.

By common traditional consent the cosmic egg was attributed to Orpheus. Whether the father was Tartaros or Erebos or Chronos is of small moment and varies from author to author. The cardinal, essential doctrine is the world-egg from which sprang the first articulate god, source and creator of all, Eros.

Damascius, in his 'Inquiry concerning first principles,'attributes the egg to Orpheus. For Orpheus said:

'What time great Chronos fashioned in holy aether

A silver-gleaming egg.'

It is fortunate that Damascius has preserved the actual line, though of course we cannot date it. Clement of Rome in his Homilies contrasts the cosmogonies of Hesiod and Orpheus. 'Orpheus likened Chaos to an egg, in which was then a blending of the primaeval elements; Hesiod assumes this chaos as a sub-stratum, the which Orpheus calls an egg, a birth emitted from formless matter, and the birth was on this wise...'Plato, usually so Orphic, avoids in the Timaeus all mention of the primaeval egg; his mind is preoccupied with triangles, but Proclus in his commentary says 'the "being" of Plato 'would be the same as the Orphic egg.'

The doctrine of the egg was not a mere dogmatic dead-letter. It was taught to the initiated as part of their mysteries, and this leads us to suspect that it had its rise in a primitive taboo on eggs. Plutarch, in consequence of a dream, abstained for a long time from eggs. One night, he tells us, when he was dining out, some of the guests noticed this, and got it into their heads that he was'infected by Orphic and Pythagorean notions, and was refusing eggs just as certain people refuse to eat the heart and brains, because he held an egg to be taboo as being the principle of life.' Alexander the Epicurean, by way of chaff, quoted,

'To feed on beans is eating parents'heads.'

As if Plutarch says, the Pythagoreans meant eggs by foans because of being and thought it just as bad to eat eggs as to eat the animals that laid them. It was no use, he goes on, in talking to an Epicurean, to plead a dream as an excuse for abstinence, for to him the explanation would seem more foolish than the fact; so, as Alexander was quite pleasant about it and a cultivated man, Plutarch let him go on to propound the interesting question, which came first, the bird or the egg? Alexander in the course of the argument came back to Orpheus and, after quoting Plato about matter being the mother and nurse, said with a smile,

'I sing to those who know

the Orphic and sacred dogma which not only affirms that the egg is older than the bird, but gives it priority of being over all things.'Finally, the speaker adds to his theorizing an instructive ritual fact: 'and therefore it is not inappropriate that in the orgiastic ceremonies in honour of Dionysos an egg is among the sacred offerings, as being the symbol of what gives birth to all things, and in itself contains all things.'

The Egg in Orphic Ritual

Macrobius in the Saturnalia states the same fact, and gives a similar reason. 'Ask those who have been initiated' he says, 'in the rites of Father Liber, in which an egg is the object of reverence, on the supposition that it is in its spherical form the image of the universe'; and Achilles Tatius says, 'some assert that the universe is cone-shaped, others egg-shaped, and this opinion is held by those who perform the mysteries of Orpheus.'

But for the bird-cosmogony of Aristophanes we might have inclined to think that the egg was a late importation into Orphic mysteries, but, the more closely Orphic doctrines are examined, the more clearly is it seen that they are for the most part based on very primitive ritual. A ritual egg was good material; those who mysticized the kid and the milk would not be likely to leave an egg without esoteric significance.

How, precisely, the egg was used in Orphic ritual we do not know. In ordinary ceremonial it served two purposes: it was used for purification, it was an offering to the dead. It has been previously shown in detail that in primitive rites purgation often is propitiation of ghosts and sprites, and the two functions, propitiation and purgation, are summed up in the common term devotions. Lucian in two passages mentions eggs, together with Hecate's suppers, as the refuse of 'purification.' Pollux is bidden by Diogenes to tell the Cynic Menippus, when he comes down to Hades, to 'fill his wallet with beans, and if he can he is to pick up also a Hecate's supper or an egg from a purification or something of the sort'; and in another dialogue, the 'Landing,' Clotho, who is waiting for her victims, asks 'Where is Kyniskos the philosopher who ought to be dead from eating Hecate's suppers and eggs from purification and raw cuttle fish too?' Again in Ovid's Art of Love the old hag who makes purifications for the sick woman is to bring sulphur and eggs:

'Then too the aged hag must come,

And purify both bed and home,

And bid her, for lustration, proffer

With palsied hands both eggs and sulphur.'

That eggs were offered not only for a purification of the living, but as the due of the dead, is certain from the fact that they appear on Athenian white lekythoi among the objects brought in baskets to the tomb.

We think of eggs rather as for nourishment than as for purification, though the yolk of an egg is still used for the washing of hair. Doubtless, in ancient days, the cleansing action of eggs was more magical than actual. As propitiatory offerings to the dead they became 'purifications 'in general; then connection with the dead explains of course the taboo on them as food.

Still, primitive man though pious is also thrifty. A Cynic may show his atheism, and also eke out a scanty subsistence by eating 'eggs from purification'; and even the most superstitious man may have hoped that, if he did not break the egg, he might cleanse himself and yet secure a chicken. Clement says,'you may see the eggs that have been used for purifications hatched, if they are subjected to warmth': he adds instructively,'this could not have taken place if the eggs had taken into themselves the sins of the man who had been purified.'Clement's own state of mind is at least as primitive as that of the'heathen'against whom he protests. The Orphics themselves, it is clear, merely mysticized an ancient ritual. Orphism is here as elsewhere only the pouring of new wine into very old bottles.

We may say then with certainty that the cosmic egg was Orphic, and was probably a dogma based on a primitive rite. The origin of the winged Eros who sprang from it is more complex. Elements many and diverse seem to have gone to his making.

Eros as Herm

Homer knows nothing of Eros as a person; with him love is of Aphrodite. From actual local cultus Eros is strangely and significantly absent. Two instances only are recorded. Pausanias says,'The Thespians honoured Eros most of all the gods from the beginning, and they have a very ancient image of him, an unwrought stone.' 'Every four years,' Plutarch says,'the Thespians celebrated a splendid festival to Eros conjointly with the Muses.' Plutarch went to this festival very soon after he was married, before his sons were born. He seems to have gone because of a difference that had arisen between his own and his wife's people, and we are expressly told by his sons that he took his newly-married wife with him'for both the prayer and the sacrifice were her affair.'Probably they went to pray for children. Plutarch, if we may trust his own letter to his wife, was a kind husband, but the intent of the conjoint journey was strictly practical, and points to the main function of the Thespian Eros. The unwrought stone' is very remote from the winged Eros, very near akin to the rude Pelasgian Hermes himself, own brother to the Priapos of the Hellespont and Asia Minor. There seems then to have gone to the making of Eros some old wide-spread divinity of generation.

Pausanias did not know who instituted the worship of Eros among the Thespians, but he remarks that the people of Parium on the Hellespont, who were colonists from Erythrae in Ionia, worshipped him equally. He knew also of an older and a younger Eros. 'Most people' he says, 'hold that he is the youngest of the gods and the son of Aphrodite; but Olen the Lycian (again Asia Minor), maker of the most ancient hymns among the Greeks, says in a hymn to Eileithyia that she is the mother of Eros.' 'After Olen,' he goes on, 'Pamphos and Orpheus composed epic verses, and they both made hymns to Eros to be sung by the Lycomids at their rites.'

Eros As Ker Of Life

The Orphic theologist found then to his hand in local cultus an ancient god of life and generation, and in antique ritual another element quite unconnected, the egg of purification. Given an egg as the beginning of a cosmogony, and it was almost inevitable that there should emerge from the egg a bird-god, a winged thing, a source of life, more articulate than the egg yet near akin to it in potency. The art-form for this winged thing was also ready to hand. Eros is but a specialized form of the Ker; the Erotes are Keres of life, and like the Keres take the form of winged Eidola. In essence as in art-form, Keres and Erotes are near akin. The Keres, it has already been seen, are little winged bacilli, fructifying or death -bringing; but the Keres developed mainly on the dark side; they went downwards, death wards; the Erotes, instinct with a new spirit, went upwards, lifewards.

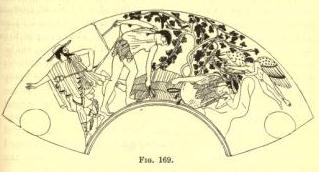

The close analogy, nay, the

identity of the art-form of Keres and Erotes is well seen in the

two vase-paintings in figs. 168 and 169. The design in fig. 168

is from a vase-fragment in the Museum at Palermo. A warrior lies

fallen in death. From his open mouth the breath of life escapes.

Over him hovers a winged Ker, and with his right hand seems as

though he would tenderly collect the parting soul. A ghost has

come to fetch a ghost. Among the Romans this gentle office of

collecting the parting breath was done with the lips, by the

nearest of kin. So Anna for Dido:

The close analogy, nay, the

identity of the art-form of Keres and Erotes is well seen in the

two vase-paintings in figs. 168 and 169. The design in fig. 168

is from a vase-fragment in the Museum at Palermo. A warrior lies

fallen in death. From his open mouth the breath of life escapes.

Over him hovers a winged Ker, and with his right hand seems as

though he would tenderly collect the parting soul. A ghost has

come to fetch a ghost. Among the Romans this gentle office of

collecting the parting breath was done with the lips, by the

nearest of kin. So Anna for Dido:

'Give water, I will bathe her wounds, and catch

Upon my lips her last stray breath.'

The design in fig. 169 is from a red-figured cylix in the Municipal Museum at Corneto. Theseus, summoned by Hermes, is in the act of deserting Ariadne; he picks up his sandal from the ground and in a moment he will be gone. Ariadne is sunk in sleep beneath the great vine of Dionysos. Over her hovers a winged genius to comfort and to crown her. He is own brother to the delicate Ker in fig. 168. Archaeologists wrangle over his name. Is he Life or Love or Sleep or Death? Who knows? It is this shifting uncertainty we must seize and hold; no doubt could be more beautiful and instructive. All that we can certainly say is that the vase-painter gave to the ministrant the form of a winged Ker, and that such was the form taken by Eros, as also by Death and by Sleep.

If we would understand at all the

spirit in which the Orphic Eros is conceived we must cleanse our

minds of many current conceptions, and in effecting this riddance

vase-paintings are of no small service. To black-figured

vase-paintings Eros is unknown. Keres of course appear, but Eros

has not yet developed personality in popular art. As soon as Eros

takes mythological shape in art, he leaves the Herm-form under

which he was worshipped at Thespiae, leaves it to Hermes himself

and to Dionysos and Priapos, and, because he is the egg-born

cosmic god, takes shape as the winged Ker. Early red-figured

vase-paintings are innocent alike of the fat boy of the Romans

and the idle impish urchin of Hellenism. Nor do they know

anything of the Eros of modern romantic passion between man and

woman. If we would follow the safe guiding of early art, we must

be content to think of Eros as a Ker, a life-impulse, a thing

fateful to all that lives, a man because of his moralized

complexity, terrible and sometimes 'intolerable, but to plants

and flowers and young live things in spring infinitely glad and

kind. Such is the Eros of Theognis:

If we would understand at all the

spirit in which the Orphic Eros is conceived we must cleanse our

minds of many current conceptions, and in effecting this riddance

vase-paintings are of no small service. To black-figured

vase-paintings Eros is unknown. Keres of course appear, but Eros

has not yet developed personality in popular art. As soon as Eros

takes mythological shape in art, he leaves the Herm-form under

which he was worshipped at Thespiae, leaves it to Hermes himself

and to Dionysos and Priapos, and, because he is the egg-born

cosmic god, takes shape as the winged Ker. Early red-figured

vase-paintings are innocent alike of the fat boy of the Romans

and the idle impish urchin of Hellenism. Nor do they know

anything of the Eros of modern romantic passion between man and

woman. If we would follow the safe guiding of early art, we must

be content to think of Eros as a Ker, a life-impulse, a thing

fateful to all that lives, a man because of his moralized

complexity, terrible and sometimes 'intolerable, but to plants

and flowers and young live things in spring infinitely glad and

kind. Such is the Eros of Theognis:

'Love comes at his hour, comes with the flowers in spring,

Leaving the land of his birth,

Kypros, beautiful isle. Love comes, scattering

Seed for man upon earth.'

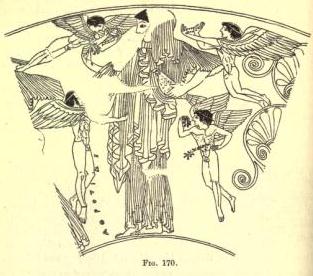

Such little spirits of life the vase-painter Hieron makes to cluster round their mother and mistress, Aphrodite. The design of a scene representing the Judgment of Paris. Aphrodite, she the victorious Gift-Giver, greatest of the Charites, stands holding her dove. About her cluster the little solemn worshipping Erotes, like the winged Keres that minister to Kyrene (fig. 23): they carry wreaths and flower-sprays in their hands, not only as gifts to the Gift-Giver, but because they too are spirits of Life and Grace.

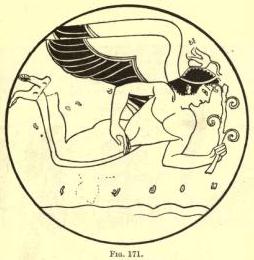

Just such another Eros is seen in fig. 171, from the centre of a beautiful archaic red-figured cylix in the Museo Civico at Florence. The cylix is signed by the master Chachrylion: he signs it twice over, proudly, as well he may, 'Chachrylion made it, made it, Chachrylion made it.' His Eros too carries a great branching flower-spray, and as the spirit of God moves upon the face of the waters. So Sophocles:

Thou of War unconquered, thou, Eros,

Spoiler of garnered gold, who liest hid

In a girl's cheek, under the dreaming lid,

While the long night time flows:

rover of the seas, terrible one

In wastes and wildwood caves,

None may escape thee, none:

Not of the heavenly Gods who live alway,

Not of low men, who vanish ere the day;

And he who finds thee, raves.

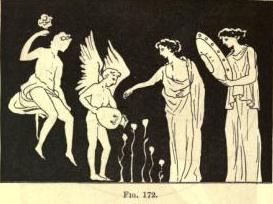

The Erotes retain always the multiplicity of the Keres, but as Eros developes complete personality he becomes one person, and he changes from a delicate sprite to a beautiful youth. But down to late days there linger about him traces of the Life-Spirit, the Grace-Giver. The design in fig. 172 is from a late red-figured vase in the Museum at Athens. Here we find Eros employed watering tall slender flowers in a garden. Of course by this time the Love-God is put to do anything and everything: degraded to a god of all work, he has to swing a maiden, to trundle a hoop, to attend a lady's toilet; but here in the flower-watering there seems a haunting of the old spirit,. We are reminded of Plato in the Symposium where he says' The bloom of his body is shown by his dwelling among flowers, for Eros has his abiding, not in the body or soul that is flowerless and fades, but in the place of fair flowers and fair scents, there sits he and abides.'

Eros as Ephebos

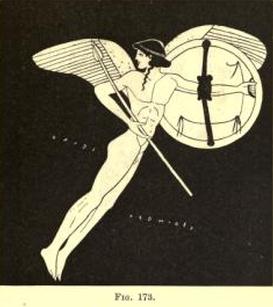

Vase-paintings with representations of Eros come to us for the most part from Athens, and it was at Athens that the art-type of Eros as the slender ephebos was perfected. This type appears with marked frequency on the vases of early red-figured technique which bear the inscription 'Charmides is beautiful', vases probably made to sell as love-gifts. Eros is represented bearing a torch, a lyre, a hare, sometimes still a flower. Perhaps the finest of these representations left us is the Eros in fig. 173. The design is from an amphora which bears the inscription 'Charmides is beautiful.' Eros is armed, he carries shield and spear, he flies straight downward, the slender naked body making a clean lovely line. A poet thinks as he will, but these Love-gods of the vase-painter, these Keres of Life and Death, and most of all this Eros, armed, inevitable, recall the prayer of the chorus in the Hippolytus of Euripides:

Eros, who blindest, tear by tear,

Men's eyes with hunger, thou swift Foe that pliest

Deep in our hearts joy like an edged spear;

Come not to me with Evil haunting near,

Wrath on the wind, nor jarring of the clear

Wing's music as thou fliest.

There is no shaft that burneth, not in fire,

Not in wild stars, far off and flinging fear

As in thine hands the shaft of All Desire,

Eros, Child of the Highest.'

Most often the presentments of painting hinder rather than help the imagery of poetry, but here both arts are haunted by the same august tradition of Life and Death.

The Eros of the vase-painter is

the love not untouched by passion of man for man; and these

sedate and even austere Erotes help us to understand that to the

Greek mind such loves were serious and beautiful, of the soul, as

Plato says, rather than of the body, aloof from common things and

from the emotional squalour of mere domestic felicity. They seem

to embody that white beat of the spirit before which and by which

the flesh shrivels into silence.

The Eros of the vase-painter is

the love not untouched by passion of man for man; and these

sedate and even austere Erotes help us to understand that to the

Greek mind such loves were serious and beautiful, of the soul, as

Plato says, rather than of the body, aloof from common things and

from the emotional squalour of mere domestic felicity. They seem

to embody that white beat of the spirit before which and by which

the flesh shrivels into silence.

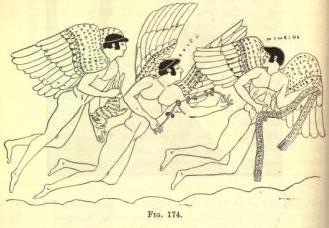

It is curious to note that, as the two women Charites, Mother and Daughter, became three, so there is a distinct effort to form a trinity of Erotes. On the vase-painting in fig. 174 from a red-figured stamnos in the British Museum we have three beautiful Erotes flying over the sea. The foremost is inscribed Himeros; he carries a long taenia, and he looks back at the others; one of these carries a tendril, the other a hare. But the triple forms, Eros, Himeros and Pothos, never really obtain. The origin of the countless women trinities has been already examined. Male gods lack the natural tie that bound the women types together; the male trinity is in Greek religion felt to be artificial and lapses.

Eros And The Mother

The mention of these women trinities brings us back to the greatest of the three Grace-Givers, Aphrodite. At the close of the chapter on The Making of a Goddess her figure reigned supreme, but for a time at Athens she suffered eclipse; we might almost say with Alcman:

'There is no Aphrodite. Hungry Love

Plays boy-like with light feet upon the flowers.'

We cannot fairly charge the eclipse of Aphrodite wholly to the count of Orphism. Legend made Orpheus a woman-hater and credited him with Hesiodic tags about her 'dog-like' nature; but such tradition is manifestly coloured and distorted by two influences, by the orthodox Hesiodic patriarchalism, and by the peculiar social conditions of Athens and other Greek states. Both these causes, by degrading women, compelled the impersonation of love to take form as a youth.

To these we must add the fact that as Orphism was based on the religion of Dionysos, and as that religion had for its god Dionysos, son of Semele, so Orphism tended naturally to the formulation of a divinity who was the Son of his Mother. By the time the religion of Dionysos reached Athens the Son had well nigh effaced the Mother, and in like fashion Eros was supreme over Aphrodite; and significantly enough the woman-goddess, in so far as she was worshipped by the Orphics, was rather the old figure of Ge, the Earth-goddess, than the more specialized departmental Love-goddess Aphrodite.

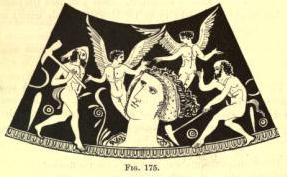

This blend of the old Earth-goddess

and the new Love-god is shown in very instructive fashion by

representations on late red-figured vases. The design in fig. 175

is from a late red-figured hydria. It will at once be seen that

we have the representation of a scene exactly similar to that in

figs. 68 and 70, the Anodos of an Earth-goddess. The great head

rises from the ground, the Satyr worshippers of the Earth-goddess

are there with their picks. But a new element is introduced. Two

Erotes hover over the goddess to greet her coming.

This blend of the old Earth-goddess

and the new Love-god is shown in very instructive fashion by

representations on late red-figured vases. The design in fig. 175

is from a late red-figured hydria. It will at once be seen that

we have the representation of a scene exactly similar to that in

figs. 68 and 70, the Anodos of an Earth-goddess. The great head

rises from the ground, the Satyr worshippers of the Earth-goddess

are there with their picks. But a new element is introduced. Two

Erotes hover over the goddess to greet her coming.

In like fashion in fig. 72 Eros receives Pandora, and in fig. 88 receives Aphrodite at her Birth or Bath. It is usual to name the goddess in fig. 175 Aphrodite. This is, I think, to miss the point. She is an Earth Kore like Persephone herself. She is the new life rising from the ground, and she is welcomed by the spirits of life, the Keres-Erotes. Beyond that we cannot go. Nothing could better embody the shift from old to new, and the blend of both, than the presence together of the Satyrs, the primitive Ge-worshippers, and the Erotes, the new spirits of love and life.

Aphrodite of the Mysteries

If we bear in mind the simple fact that Aphrodite and Persephone are each equally and alike Kore, the Maiden form of the Earth-goddess, it is not hard to realise how easily the one figure passes into the other. The Orphic, we have seen, put his faith in the Kore who is Persephone; to her he prays:

'Out of the pure I come, Pure Queen of Them Below';

his confession is

'I have sunk beneath the bosom of Despoina, Queen of the Underworld,'

and again

'But now I come a suppliant to holy Phersephoneia

That of her grace she receive me to the seats of the Hallowed';

but from the fragment of an epic poet preserved for us by the anonymous author of the Philosophoumena, we learn that, according to some, in the underworld grove another Kore, or rather Kore by another name, was believed to rule. 'The Lesser Mysteries,' he says, 'are of Persephone below, in regard to which Mysteries and the path that leads there, which is wide and large and leads the dying to Persephone, the poet also says:

And yet'neath it there is a rugged track, Hollow, bemired; yet best whereby to reach All-hallowed Aphrodite's lovely grove."'

The figures of the two Maidens, Persephone and Aphrodite, acted and reacted on each other; Persephone takes on more of Love, Aphrodite more of Death; as Eros the Son waxes, Aphrodite the Mother wanes into Persephone the underworld Maid.

The blend of the two notions, the primitive Earth-goddess and the Orphic Eros, is for art very clearly seen on the vase in fig. 175. Happily we have definite evidence that in local cultus there was the like fusion, and that at a place of associations specially sacred, the deme of Phlya in Attica, the birthplace of Euripides.

THE MYSTERIES OF EROS AND THE MOTHER AT PHLYA.

Phlya, as the birthplace of Euripides, has special claims on our attention. Here, it will be shown, were mysteries reputed to be more ancient than those of Eleusis, mysteries not only of the Mother and the Maid but of Eros the cosmic spirit of the Orphics.

Euripides, obviously hostile as he is to orthodox Olympian theology, handles always with reverence the two gods or spirits of Orphism, Dionysos and Eros; it seems not improbable that, perhaps unconsciously, the mysteries of his early home may have influenced his religious attitude.

From Pausanias we learn that Phlya had a cult of the Earth-goddess. She was worshipped together with a number of other kindred divinities.'Among the inhabitants of Phlya there are altars of Artemis the Light-Bearer, and of Dionysos Anthios, and of the Ismenian Nymphs, and of Ge, whom they call the Great Goddess. And another temple has altars of Demeter Anesidora, and of Zeus Ktesios, and of Athene Tithrone, and of Kore Protogene, and of the goddesses called Venerable.'

The district of Phlya is still well watered and fertile, still a fitting home for Dionysos 'of the Flowers,' and for Demeter 'Sender up of Gifts'; probably it took its name from this characteristic fertility. Plutarch discussed with some grammarians at dessert the reason why apples were called by Empedocles 'very fruitful.' Plutarch made a bad and unmetrical guess; he thought the word was connected with husk or rind, and that the apple was called 'because all that was eatable in it lay outside the inner rind-like core.' The grammarians knew better; they pointed out that Arafcus used the word to mean verdure and blossoming, the'greenness and bloom of fruits,'and they added the instructive statement that 'certain of the Greeks sacrificed to Dionysos Phloios,' He of blossom and growth.'Dionysos Phloios and Dionysos Anthios are one and the same potency.

Mysteries at Phlya

Among this family group of ancient earth divinities Artemis and Zeus read like the names of late Olympian intruders. Artemis as Light-Bearer may have taken over an ancient mystery cult of Hecate, who also bore the title of Phosphoros; Zeus Ktesios, we are certain, is not the Olympian. Like Zeus Meilichios he has taken over the cult of an old divinity of'acquisition'and fertility. 'Zeus' Ktesios was the god of the storeroom. Harpocration says, 'they set up Zeus Ktesios in storerooms.' The god himself lived in a jar. In discussing the various shapes of vessels Athenaeus says of the kadiskos, 'it is the vessel in which they consecrate the Ktesian Zeuses, as Antikleides says in his "Interpretations," as follows the symbols of Zeus Ktesios are consecrated as follows:

"the lid must be put on a new kadiskos with two handles, and the handles crowned with white wool ...... and you must put into it whatever you chance to find and pour in ambrosia. Ambrosia is pure water, olive oil and all fruits. Pour in these."'

Whatever are the obscurities of the account of Antikleides, thus much is clear Zeus Ktesios is not the Olympian of the thunderbolt, he is Zeus in nothing but his name. Ktesios is clearly an old divinity of fertility, of the same order as Meilichios; his crrjuela are symbols not statues, symbols probably like the sacra carried in chests at the Arrephoria; they are dea-poi, magical spells kept in a jar for the safe guarding of the storeroom. Zeus Ktesios is well in place at Phlya. The great pithoi that in Homer stand on the threshold of Olympian Zeus may be the last reminiscence of this earlier Dian daemon who had his habitation, genius-like, in a jar.

But this old daemon of fertility who took on the name of Zeus only concerns us incidentally. In the complex of gods enumerated by Pausanias as worshipped at Phlya, the Great Goddess is manifestly chief. The name given to Kore, Protogene, suggests Orphism, but we are not told that it was a mystery cult, and of Eros there is no notice. Happily from other sources we know further particulars. In discussing the parentage of Themistocles Plutarch asserts that Themistocles was related to the family of the Lycomids. 'This is clear,' he says, 'for Simonides states that, when the Telesterion at Phlya, which was the common property of the gens of the Lycomids, was burnt down by the barbarians, Themistocles himself restored it and decorated it with paintings.' In this Telesterion, this 'Place of Initiation' the cult of Eros was practised. The evidence is slight but sufficient. In discussing the worship of Eros at Thespiae Pausanias states incidentally, we already noted, that the poets Pamphos and Orpheus both composed'poems about Eros to be chanted by the Lycomids over their rites.'

This mystery cult, we further know, was also addressed to a form of the Earth goddess. When actually at Phlya, Pausanias, as already noted, curiously enough says nothing of mysteries; he simply notes that the Great Goddess and other divinities were worshipped there. Probably by his time the mystery cult of Phlya was completely overshadowed and obscured by the dominant, orthodox rites at Eleusis. But, apropos of the mysteries at Andania in Messene, he gives significant details about Phlya. He tells us three facts which all go to show that the cult at Phlya was a mystery-cult. First, the mysteries of Andania were, he says, brought there by a grandson of Phlyos; and this Phlyos, we may conclude, was the eponymous hero of Phlya. Second, for the Lycomids, who, we have seen, had a 'Place of Initiation' at Phlya and hymns to Eros, Musaeus wrote a hymn to Demeter, and in this hymn it was stated that Phlyos was a son of Ge. Third, Methapos, the great 'deviser of rites of initiation,' had a statue in the sanctuary of the Lycomids, the metrical inscription on which Pausanias quotes. In view of this evidence it cannot be doubted that the cult of Phlya was a mystery-cult, and the divinities worshipped among others were the Mother and the Maid and Eros.

At Phlya then, it is clear, we have just that blend of divinities that appears on the vase-painting in fig. 175. We have the worship of the great Earth-goddess who was Mother and Maid in one, and, conjointly, we have the worship of the Orphic spirit of love and life, Eros. It is probable that the worship of the Earth-goddess was primaeval, and that Eros was added through Orphic influence.

The Eros of the Athenian vase-painting is the beautiful Attic boy, but there is evidence to show that the Eros of Phlya was conceived of as near akin in form to a Herm. In discussing the Orphic mysteries, we found that at Phlya according to the anonymous author of the Philosophoumena there was a bridal-chamber decorated with paintings. This bridal chamber was probably the whole or a part of that Telesterion which was restored and decorated by Themistocles. The subjects of these paintings Plutarch had fully discussed in a treatise now unhappily lost. The loss is to be the more deeply regretted because the account by Plutarch of pictures manifestly Orphic would have been sympathetic and would greatly have helped our understanding of Orphism. The author of the Philosophoumena describes briefly one picture and one picture only, as follows: 'There is in the gateway the picture of an old man, white-haired, winged; he is pursuing a blue-coloured woman who escapes. Above the man is written aos pvevrijs, above the woman treperifikba. According to the doctrine of the Sethians, it seems that aop pvevrrs is light and that fifcba is dark water.' The exact meaning of these mysterious paintings is probably lost for ever; but it is scarcely rash to conjecture that the male figure is Eros. He pursues a woman; he is winged; that is like the ordinary Eros of common mythology. But this is the Eros of the mysteries; not young, but very ancient, and white-haired, the dpxalos epos of Orphic tradition, eldest of all the Gods. And the name written above him as he pursues his bride inscribed 'Darkness' or 'Dark Water' is 'Phaos Ruentes,' 'The rushing or streaming Light.' We are reminded of the time when'the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.' The ancient Eros of Thespiae, who was in intent a Herm, has become the principle not only of Life but of Light Light pursuing and penetrating Darkness. Exactly such a being, such a strange blend of animal and spiritual, is the egg-born Protogonos of the Orphic hymn:

'Thou tempest spirit in all the ordered world

On wild wings flashing; bearer of bright light

And holy; therefore Phanes named, and Lord

Priapos, and the Dawn that answereth Dawn.'

So chants the mystic, seeking to utter the unutterable, and the poet, born in the home of mysticism, sings to Mother and Son:

'Thou comest to bend the pride

Of the hearts of God and man,

Cypris; and by thy side

In earth's encircling span

He of the changing plumes,

The Wing that the world illumes,

As over the leagues of land flies he,

Over the salt and sounding sea.

For mad is the heart of Love,

And gold the gleam of his wing;

And all to the spell thereof

Bend, when he makes his spring;

All life that is wild and young,

In mountain and wave and stream,

All that of earth is sprung

Or breathes in the red sunbeam.

Yea and Mankind. O'er all a royal throne,

Cyprian, Cyprian, is thine alone.'

Pythagorean Revivals Of The Mother

The development of the male Eros, the beautiful youth, was due, we may be sure, to influences rather Athenian than Orphic. In this connection it is important to note that the Orphic Pythagoreans tended to revive religious conceptions that were matriarchal rather than patriarchal. The religion of Dionysos, based on the worship of Mother and Son, gave to women a freedom and a consequence possible only perhaps among the more spiritual peoples of the North. Under Pythagoras we have clear indications of a revival of the like conditions, of course with a difference, a resurgence as it were of matriarchal conditions, and with it a realization of the appeal of women to the spirit as well as the flesh.

According to Aristoxenus Pythagoras got most of his ethical lore from a woman, Themistoclea, a priestess of Delphi. We are reminded of Socrates and Diotima, Diotima the wise woman of Man tinea, which has yielded up to us the great inscription dealing with the mysteries of Demeter at Andania. We are reminded too of the close friendship between Plutarch and the Thyiad, Clea. It was to a woman, his daughter Damo, that Pythagoras entrusted his writings with orders to divulge them to no outside person. Diogenes further records with evident surprise that men'gave their wives into the charge of Pythagoras to learn somewhat of his doctrine,'and that these women were called 'Pythagoreans.' Kratinos wrote a comedy on these Pythagorean women in which he ridiculed Pythagoras; so we may be sure his women followers were not spared. This Pythagorean woman movement probably suggested some elements in the ideal state of Plato, and may have prompted the women comedies of Aristophanes. Of a woman called Arignote we learn that 'she was a disciple of the famous Pythagoras and of Theano, a Samian and a Pythagorean philosopher, and she edited the Bacchic books that follow: one is about the mysteries of Demeter, and the title of it is the Sacred Discourse, and she was the author of the Rites of Dionysos and other philosophical works.' That this matriarchalism of Pythagoras was a revival rather than an innovation seems clear. Iamblichus says, 'whatever bore the name of Pythagoras bore the stamp of antiquity and was crusted with the patina, archaism.'

It is not a little remarkable that, in his letter to the women of Croton, Pythagoras says expressly that'women as a sex are more naturally akin to piety.'He says this reverently, not as Strabo does taking it as evidence of ignorance and superstition. Strabo in discussing the celibate customs of certain among the Getae remarks, 'all agree that women are the prime promoters of superstition, and it is they who incite men to frequent worshippings of the gods and to feasts and excited celebrations.' He adds with charming frankness 'you could scarcely find a man living by himself who would do this sort of thing.' It is to Pythagoras, as has already been noted, that we owe the fertile suggestion that in the figures of the women goddesses we have the counterpart of the successive stages of a woman's life as Maiden, Bride and Mother.

The doctrine of the Pythagoreans in their lifetime was matriarchal and in their death they turned to Mother Earth. The house of Pythagoras after his death was dedicated as a sanctuary to Demeter, and Pliny records significant fact that the disciples of Pythagoras reverted to the ancient method of inhumation long superseded by cremation and were buried in pithoi, earth to earth.

EROS AS PHANES, PROTOGONOS, METIS, ERIKAPAIOS.

The Eros of Athenian poetry and painting is unquestionably male, but the Protogonos of esoteric doctrine is not male or female but bisexed, resuming in mystic fashion Eros and Aphrodite. He is an impossible, unthinkable cosmic potency. The beautiful name of Eros is foreign to Orphic hymns. Instead we have Metis, Phanes, Erikapaios,'which being interpreted in the vulgar tongue are Counsel, Light and Lifegiver.' The commentators on Plato are iscious of what Plato himself scarcely realizes, that in his Philosophy he is always trying to articulate the symbolism of these and other Orphic titles, trying like Orpheus to utter the unutterable; he puts vovs for Metis, to ov for Erikapaios, but, in despair, he constantly lapses back into myth and we have the winged soul, the charioteer, the four-square bisexed man. Proklos knows that to ovis but the primaeval egg, knows too that Erikapaios was male and female:

'Father and Mother, the mighty one Erikapaios,'

and Hermias knows that Orpheus made Phanes four-square:

'He of the fourfold eyes, beholding this way, that way.'

It was 'the inspired poets,' Hermias says, 'not Plato, who invented the charioteer and the horses' and these inspired poets are according to him Homer, Orpheus, Parmenides.

The mention of Homer comes as something of a shock; but it must be remembered that the name Homer covered in antiquity a good deal more than our Iliad and Odyssey. It is not unlikely that some of the 'Homeric' poems were touched with Orphism. The name Metis suggests it. The strange denaturalized birth of Athene from the brain of Zeus is a dark, desperate effort to make thought the basis of being and reality, and the shadowy parent in the Kypria is the Orphic Metis. Athene, as has already been shown, was originally only one of the many local Korae; she was the 'maiden of Athens,' born of the earth, as much as the Kore of Eleusis. Patriarchalism wished to rid her of her matriarchal ancestry, and Orphic mysticism was ready with the male parent Metis. The proud rationalism of Athens, uttering itself in a goddess who embodied Reason, did the rest.

There is a yet more definite tinge

of Orphism in the story of Leda and the swan. Leda herself is all

folklore and faery story based probably on a cultus-object. In

the sanctuary of the ancient Maidens Hilaira and Phoebe at Sparta

there hung from the roof suspended by ribbons an egg, and

tradition said it was the egg of Leda. But the author of the

Kypria gave to Zeus another bride, Nemesis, who belongs to the

sisterhood of shadowy Orphicized female impersonations, Dike,

Ananke, Adrasteia and the like. The birth of the child from the

egg appears on no black-figured vase-painting, and though it need

not have been originated by the Orphics, the birth of Eros

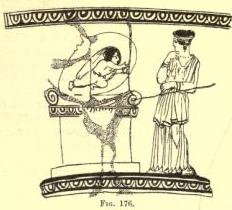

doubtless lent it new prestige. The charming little design in

fig. 176 is from a red-figured lekythos in the Berlin Museum. On

an altar lies a huge egg. Out of it breaks the figure of a boy.

The boy is not winged; otherwise we should be inclined to call

him Eros. The woman to whom the child stretches out his hands

must be Leda. The scene is the birth of one of the Dioscuri, but

probably with some reminiscence of Eros. On most vases in which

the birth from the egg is represented it takes place in a

sanctuary.

There is a yet more definite tinge

of Orphism in the story of Leda and the swan. Leda herself is all

folklore and faery story based probably on a cultus-object. In

the sanctuary of the ancient Maidens Hilaira and Phoebe at Sparta

there hung from the roof suspended by ribbons an egg, and

tradition said it was the egg of Leda. But the author of the

Kypria gave to Zeus another bride, Nemesis, who belongs to the

sisterhood of shadowy Orphicized female impersonations, Dike,

Ananke, Adrasteia and the like. The birth of the child from the

egg appears on no black-figured vase-painting, and though it need

not have been originated by the Orphics, the birth of Eros

doubtless lent it new prestige. The charming little design in

fig. 176 is from a red-figured lekythos in the Berlin Museum. On

an altar lies a huge egg. Out of it breaks the figure of a boy.

The boy is not winged; otherwise we should be inclined to call

him Eros. The woman to whom the child stretches out his hands

must be Leda. The scene is the birth of one of the Dioscuri, but

probably with some reminiscence of Eros. On most vases in which

the birth from the egg is represented it takes place in a

sanctuary.

Homeric theology, as we know it in our canonical Homer, was wholly untouched by Orphism. The human figures of the Olympians, clear-cut and departmental as they are, have no kinship with the shifting mystical Protogonos. The Olympians lay no claim to be All in All, nor are they in any sense Creators, sources of life. Homer has no cosmogony, only a splendid ready-made human society. His gods are immortal because death would shadow and mar their splendour, not because they are the perennial sources of things. It is noticeable that Zeus himself, the supreme god of Homeric theology, can only be worked into the Orphic system by making him become Eros, and absorb Phanes; only so can he become demiourgos, a feat which, to do him justice, he never on his own account attempted. Proklos says 'Orpheus in inspired utterance declares that Zeus swallowed Phanes his progenitor, and took into his bosom all his powers.' This mysticism was of course made easy by savage cosmogonies of Kronos and the swallowing of the children.

The Orphic Pan

The Olympians concern themselves as little with the Before as with the Hereafter; they are not the source of life nor are they its goal. Moreover, another characteristic is that they are, with the strictest limitations, human. They are not one with the life that is in beasts and streams and woods as well as in man. Eros,'whose feet are on the flowers/ who'couches in the folds,'is of all life, he is Dionysos, he is Pan. Under Athenian influence Eros secludes himself into purely human form, but the Phanes of Orpheus was polymorphic, a beast-mystery-god:

'Heads had he many,

Head of a ram, a bull, a snake, and a bright-eyed lion.'

He is like Dionysos, to whom his Bacchants cry:

'Appear, appear, whatso thy shape or name,

O Mountain Bull, Snake of the Hundred Heads,

Lion of the Burning Flame!

God, Beast, Mystery, come!'

In theology as in ritual Orphism reverted to the more primitive forms, lending them deeper and intenser significance. These primitive forms, shifting and inchoate, were material more malleable than the articulate accomplished figures of the Olympians.

The conception of Phanes Protogonos remained always somewhat esoteric, a thing taught in mysteries, but his content is popularized in the figure of the goat-god who passed from being the feeder, the shepherd, to be Pan the All-God.

Pan came to Athens from Arcadia after the Persian War, came at a time when scepticism was busy with the figures of the Olympians and their old prestige was on the wane. Pan of course had to have his reception into Olympus, and a derivation duly Olympian was found for his name. The Homeric Hymn, even if it be of Alexandrian date, is thoroughly Homeric in religious tone: the poet tells how

'Straight to the seats of the gods immortal did Hermes fare

With his child wrapped warmly up in skins of the mountain hare,

And down by the side of Zeus and the rest, he made him to sit,

And showed him that boy of his, and they all rejoiced at it.

But most of all Dionysos, the god of the Bacchanal,

And they called the name of him PAN because he delighted them ALL.'

Dionysos the Bull-god and Pan the Goat-god both belong to early pre-anthropomorphic days, before man had cut the ties that bound him to the other animals; one and both they were welcomed as saviours by a tired humanity. Pan had no part in Orphic ritual, but in mythology as the All-god he is the popular reflection of Protogoaos. He gave a soul of life and reality to a difficult monotheistic dogma, and the last word was not said in Greek religion, until over the midnight sea a voice was heard crying 'Great Pan is dead.'

The Mystic Dionysos

Our evidence for the mystic Phanes Protogonos, as distinguished from the beautiful Eros of the Athenians, has been, so far, drawn from late and purely learned authors, commentators on Plato, Christian Fathers, and the like. The suspicion may lurk in some minds that all this cosmogony, apart from the simple myth of the world-egg vouched for by Aristophanes, is a matter of late mysticizing, and never touched popular religion at all, or if at all, not till the days of decadence. It is most true that'the main current of speculation, as directed by Athens, set steadily contrariwise, in the line of getting bit by bit at the meaning of things through hard thinking,' but we need constantly to remind ourselves of the important fact'that the mystical and "enthusiastic" explanation of the world was never without its apostles in Greece.' That the common people heard this doctrine gladly is curiously evidenced by the next monument to be discussed, a religious document of high value, the fragment of a black-figured vase-painting in fig. 177.

In the sanctuary of the Kabeiroi

near Thebes there came to light a mass of fragments of

black-figured vases, dating about the end of the 5th or the

beginning of the 4th century B.C., of local technique and

obviously having been used in a local cult. The important

inscribed fragment is here reproduced. The reclining man holding

the kantharos, would, if there were no inscription, be named

without hesitation Dionysos. But over him is clearly written

Kabiros.

In the sanctuary of the Kabeiroi

near Thebes there came to light a mass of fragments of

black-figured vases, dating about the end of the 5th or the

beginning of the 4th century B.C., of local technique and

obviously having been used in a local cult. The important

inscribed fragment is here reproduced. The reclining man holding

the kantharos, would, if there were no inscription, be named

without hesitation Dionysos. But over him is clearly written

Kabiros.

Goethe makes his Sirens say of the Kabeiroi that they

'Sind Gotter, wundersam eigen,

Die sich immerfort selbst erzeugen

Und niemals wissen was sie sind.'

They have certainly a wondrous power of taking on the forms of other deities; here in shape and semblance they are Dionysos, the father and the son. Very surprising are the other inscribed figures, a man and a woman closely linked together, Mitos and Krateia, and a child Protolaos. What precisely is meant by the conjunction is not easy to say, but the names Mitos and Protolaos take us straight to Orphism. Clement says in the Stromata that Epigenes wrote a book on the poetry of Orpheus and'in it noted certain characteristic expressions.'Among them was this, that by warp Orpheus meant furrow, and by woof he meant seed.

Did this statement stand alone we might naturally dismiss it as late allegorizing, but here, on a bit of local pottery of the 5th or 4th century B.C., we have the figure of Mitos in popular use. All the Theban Kabeiroi vases are marked by a spirit of grotesque and sometimes gross caricature. Mitos, Krateia and Protolaos it will be noted have snub negro faces. This gives us a curious glimpse into that blending of the cosmic and the mystic, that concealing of the sacred by the profane, that seems inherent in the anxious primitive mind. It makes us feel that Aristophanes, to his own contemporaries, may have appeared less frankly blasphemous than he seems to us.

The vase fragment has another interest. The little Orphic cosmogonic group, Seed and Strong One and First people, the birth of the human world as it were, is in close connection with Dionysos, the father and the son. It is all like a little popular diagram of the relation of Orphic and Bacchic rites, and moreover it comes to us from the immediate neighbourhood of Thebes, the reputed birthplace of the god.

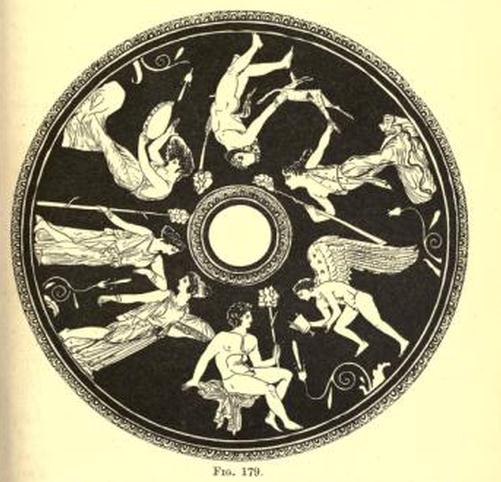

The vase fragment from Thebes shows

plainly the influence of mystery doctrines on popular conceptions

of Dionysos. It is worth noting that in red-figured

vase-paintings of a somewhat late style Eros comes to be a

frequent attendant on Dionysos, whereas in vases of severe style

he is wholly absent, Maenads and Satyrs revel either together or

alone. The design in fig. 179, from the lid of a red-figured

lekane (fig. 178) in the Museum at Odessa, is a singularly

beautiful instance of Eros as present at a Bacchic revel. A

Maenad and a Satyr dance in ecstasy, holding between them a

little fawn, as though in the act of rending it asunder. Over her

long chiton, that trails and swirls about her feet in oddly

modern fashion, the Maenad wears a fawn-skin; a second dancing

Maenad strikes her timbrel. One half of the design is all ecstasy

and even savagery, the other half is perfectly quiet. Two Maenads

stand talking, at rest; the god Dionysos is seated and Eros

offers him the wine-cup. Here it is Eros the son, not Aphrodite

the mother, who is linked with Dionysos, but we remember how in

the Bacchae of Euripides the Messenger thus pleads with

Pentheus:

The vase fragment from Thebes shows

plainly the influence of mystery doctrines on popular conceptions

of Dionysos. It is worth noting that in red-figured

vase-paintings of a somewhat late style Eros comes to be a

frequent attendant on Dionysos, whereas in vases of severe style

he is wholly absent, Maenads and Satyrs revel either together or

alone. The design in fig. 179, from the lid of a red-figured

lekane (fig. 178) in the Museum at Odessa, is a singularly

beautiful instance of Eros as present at a Bacchic revel. A

Maenad and a Satyr dance in ecstasy, holding between them a

little fawn, as though in the act of rending it asunder. Over her

long chiton, that trails and swirls about her feet in oddly

modern fashion, the Maenad wears a fawn-skin; a second dancing

Maenad strikes her timbrel. One half of the design is all ecstasy

and even savagery, the other half is perfectly quiet. Two Maenads

stand talking, at rest; the god Dionysos is seated and Eros

offers him the wine-cup. Here it is Eros the son, not Aphrodite

the mother, who is linked with Dionysos, but we remember how in

the Bacchae of Euripides the Messenger thus pleads with

Pentheus:

'Therefore I counsel thee,

King, receive this Spirit whoe'er he be

To Thebes in glory. Greatness manifold

Is all about him and the tale is told

That this is he who first to man did give

The grief-assuaging vine. Oh, let him live,

For if he die, then Love herself is slain;

And nothing ioyous in the world again.'

Eros and Dionysos, the poet sees, are near akin; both are spirits of Life and of Life's ecstasy.

Dionysos like Eros is a daimon, a spirit rather than a clear-cut crystallized god; he is as has been already seen of many shapes, of plants and animals as well as man, so he like Eros becomes Phanes:

'Therefore him we call both Phanes and Dionysos.'

Dionysos is but a new ingredient in the monotheistic mystery melting-pot:

'One Zeus, one Hades, one Helios, one Dionysos,

Yea in all things One God, his name why speak I asunder?'

In becoming the Orphic Phanes Dionysos lost most of his characteristics. In spite of his persistent monotheism we are somehow conscious that Orpheus did not feel all the gods to be really one, all equal manifestations of the same potency. He is concerned to push the claims of the cosmic Eros as against the simpler wine god. Possibly he felt that Dionysos needed much adjustment and was not always for edification. Of this we have some hint in the last literary document to be examined.

In the statutes of the lobacchoi at Athens, we have already seen, the thyrsos became the symbol not of revel but of quiet seemliness. We shall now find that though by name and tradition they are pledged to the worship of Dionysos the lobacchoi have introduced into their ceremonies a figure more grave and orderly, a figure bearing in the inscription a name of beautiful significance, Proteurhythmos. A part of their great festival consisted in a sacred pantomime, the rdles in which were distributed by lot. The divine persons represented were 'Dionysos, Kore, Palaimon, Aphrodite, and Proteurhythmos.' Who was Proteurythmos, First of fair rhythm? The word defies translation into English, but its initial syllable first, at once inclines us to see in it an Orphic title like Protogonos or Protolaos. The word has indeed been interpreted as a title of Orpheus himself, Orpheus Proteurhythmos, First dancer or singer. Such an interpretation argues, I think, a grave misunderstanding. It ignores the juxtaposition of Proteurhythmos with Aphrodite and rests for support on the initial error that Orpheus himself is a faded god. Proteurhythmos is, I think, not Orpheus, but a greater than he, the god whom he worshipped, Eros Protogonos. Orpheus is a musician, but it was Eros, not Orpheus, who gave impulse and rhythm to the great dance of creation when'the Morning Stars sang together.'Eros, not Orpheus, is demiourgos.

Lucian knew this. 'It would seem that dancing came into being at the beginning of all things, and was brought to light together with Eros, that ancient one, for we see this primaeval dancing clearly set forth in the choral dance of the constellations, and in the planets and fixed stars, their interweaving and interchange and orderly harmony.'

It is the primaeval life that Eros, not Orpheus, begets within us, that wakes now and again, that feels the rhythm of a poem, the pulse of a pattern and the chime of a dancer's feet.

'In the beginning when the sun was lit

The maze of things was marshalled to a dance.

Deep in us lie forgotten strains of it,

Like obsolete, charmed sleepers of romance.

And we remember, when on thrilling strings

And hollow flutes the heart of midnight burns,

The heritage of splendid, moving things

Descends on us, and the old power returns.'

Eros is Lord of Life and Death, he is also Proteurhythmos, but because of the bitter antinomy of human things to man he is also Lord of Discord and Misrule. And therefore the chorus in the Bippolytus, brooding over the sickness and disorder of Phaedra, prays:

'When I am thine, Master, bring thou near

No spirit of evil, make not jarred the clear

Wings'music as thou fliest.'

The gods whose worship Orpheus taught were two, Bacchus and Eros; in actual religion chiefly Bacchus, in mystical dogma Eros, and in ancient Greek religion these are the only real gods. Orpheus dimly divined the truth, later to become explicit through Euripides of Phlya:

'I saw that there are first and above all

The hidden forces, blind necessities

Named Nature, but the things self-unconceived.

We know not how imposed above ourselves,

We well know what I name the god, a power

Various or one.'

Through all the chaos of his cosmogony and the shifting, uncertain outlines of his personifications, we feel, in these two gods, lies the real advance of the religion of Orpheus an advance, not only beyond the old riddance of ghosts and sprites and demons, but also beyond the gracious and beautiful service of those magnified mortals, the Olympians. The religion of Orpheus is religious in the sense that it is the worship of the real mysteries of life, of potencies rather than personal gods; it is the worship of life itself in its supreme mysteries of ecstasy and love. "Reason is great, but it is not everything. There are in the world things, not of reason, but both below and above it, causes of emotion which we cannot express, which we tend to worship, which we feel perhaps to be the precious things in life. These things are God or forms of God, not fabulous immortal men, but 'Things which Are,' things utterly non-human and non-moral which bring man bliss or tear his life to shreds without a break in their own serenity."

It is these real gods, this life itself, that the Greeks, like most men, were inwardly afraid to recognize and face, afraid even to worship. Orpheus too was afraid the garb of the ascetic that he always wears is the token at once of his realization and his fear but at least he dares to worship. Now and again a philosopher or a poet, in the very spirit of Orpheus, proclaims these true gods, and asks in wonder why to their shrines is brought no sacrifice. Plato in the Symposium makes Aristophanes say, 'Mankind would seem to have never realized the might of Eros, for if they had really felt it they would have built him great sanctuaries and altars and offered solemn sacrifices, and none of these things are done, but of all things they ought to be done. Euripides in the Hippolytus makes his chorus sing:

'In vain, in vain by old Alpheus'shore,

The blood of many bulls doth stain the river,

And all Greece bows on Phoebus' Pythian floor,

Yet bring we to the Master of Man no store,

The Keybearer that standeth at the door

Close barred, where hideth ever

Love's inmost jewel. Yea, though he sack man's life,

Like a sacked city and moveth evermore,

Girt with calamity and strange ways of strife,

Him have we worshipped never.'

To resume: the last word in ancient Greek religion was said by the Orphics, and the beautiful figure of Orpheus is strangely modern. Then, as now, we have, for one side of the picture, a revived and intensified spirituality, an ardent, even ecstatic enthusiasm, a high and self-conscious standard of moral conduct, a deliberate simplicity of life; abstinence from many things, temperance in all, a great quiet of demeanour, a marvellous gentleness to all living things.

And, for the reverse, we have formalism, faddism, priggishness, a constant, and it would seem inevitable lapse into arid symbolism, pseudo-science, pseudo-philosophy, the ignorant revival of obsolete rites, the exhibition of all manner of ignoble thaumaturgy and squalid credulity. The whole strange blend redeemed, illuminated by two impulses, in practice by the strenuous effort after purity of life, in theory by the 'further determination of the Absolute' into the mysticism of Love.