On the Spanish Main, by John Masefield

CHAPTER IX

BUCCANEER CUSTOMS

Mansvelt and Morgan—Morgan's raid on Cuba—Puerto del Principe

Throughout the years of buccaneering, the buccaneers often put to sea in canoas and periaguas,[15] just as Drake put to sea in his three pinnaces. Life in an open boat is far from pleasant, but men who passed their leisure cutting logwood at Campeachy, or hoeing tobacco in Jamaica, or toiling over gramma grass under a hot sun after cattle, were not disposed to make the worst of things. They would sit contentedly upon the oar bench, rowing with a long, slow stroke for hours together without showing signs of fatigue. Nearly all of them were men of more than ordinary strength, and all of them were well accustomed to the climate. When they had rowed their canoa to the Main they were able to take it easy till a ship came by from one of the Spanish ports. If she seemed a reasonable prey, without too many guns, and not too high charged, or high built, the privateers would load their muskets, and row down to engage her. The best shots were sent into the bows, and excused from rowing, lest the exercise should cause their hands to tremble. A clever man was put to the steering oar, and the musketeers were bidden to sing out whenever the enemy yawed, so as to fire her guns. It was in action, and in action only, that the captain had command over his men. The steersman endeavoured[130] to keep the masts of the quarry in a line, and to approach her from astern. The marksmen from the bows kept up a continual fire at the vessel's helmsmen, if they could be seen, and at any gun-ports which happened to be open. If the helmsmen could not be seen from the sea, the canoas aimed to row in upon the vessel's quarters, where they could wedge up the rudder with wooden chocks or wedges. They then laid her aboard over the quarter, or by the after chains, and carried her with their knives and pistols. The first man to get aboard received some gift of money at the division of the spoil.

When the prize was taken, the prisoners were questioned, and despoiled. Often, indeed, they were stripped stark naked, and granted the privilege of seeing their finery on a pirate's back. Each buccaneer had the right to take a shift of clothes out of each prize captured. The cargo was then rummaged, and the state of the ship looked to, with an eye to using her as a cruiser. As a rule, the prisoners were put ashore on the first opportunity, but some buccaneers had a way of selling their captives into slavery. If the ship were old, leaky, valueless, in ballast, or with a cargo useless to the rovers, she was either robbed of her guns, and turned adrift with her crew, or run ashore in some snug cove, where she could be burnt for the sake of the iron-work. If the cargo were of value, and, as a rule, the ships they took had some rich thing aboard them, they sailed her to one of the Dutch, French, or English settlements, where they sold her freight for what they could get—some tenth or twentieth of its value. If the ship were a good one, in good condition, well found, swift, and not of too great draught (for they preferred to sail in small ships), they took her for their cruiser as soon as they had emptied out her freight. They sponged and loaded her guns, brought their stores aboard her, laid their mats upon her deck, secured the boats astern, and sailed[131] away in search of other plunder. They kept little discipline aboard their ships. What work had to be done they did, but works of supererogation they despised and rejected as a shade unholy. The night watches were partly orgies. While some slept, the others fired guns and drank to the health of their fellows. By the light of the binnacle, or by the light of the slush lamps in the cabin, the rovers played a hand at cards, or diced each other at "seven and eleven," using a pannikin as dice-box. While the gamblers cut and shuffled, and the dice rattled in the tin, the musical sang songs, the fiddlers set their music chuckling, and the sea-boots stamped approval. The cunning dancers showed their science in the moonlight, avoiding the sleepers if they could. In this jolly fashion were the nights made short. In the daytime, the gambling continued with little intermission; nor had the captain any authority to stop it. One captain, in the histories, was so bold as to throw the dice and cards overboard, but, as a rule, the captain of a buccaneer cruiser was chosen as an artist, or navigator, or as a lucky fighter. He was not expected to spoil sport. The continual gambling nearly always led to fights and quarrels. The lucky dicers often won so much that the unlucky had to part with all their booty. Sometimes a few men would win all the plunder of the cruise, much to the disgust of the majority, who clamoured for a redivision of the spoil. If two buccaneers got into a quarrel they fought it out on shore at the first opportunity, using knives, swords, or pistols, according to taste. The usual way of fighting was with pistols, the combatants standing back to back, at a distance of ten or twelve paces, and turning round to fire at the word of command. If both shots missed, the question was decided with cutlasses, the man who drew first blood being declared the winner. If a man were proved to be a coward he was either tied to the mast, and[132] shot, or mutilated, and sent ashore. No cruise came to an end until the company declared themselves satisfied with the amount of plunder taken. The question, like all other important questions, was debated round the mast, and decided by vote.

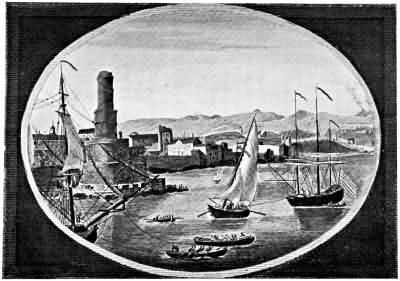

At the conclusion of a successful cruise, they sailed for Port Royal, with the ship full of treasure, such as vicuna wool, packets of pearls from the Hatch, jars of civet or of ambergris, boxes of "marmalett" and spices, casks of strong drink, bales of silk, sacks of chocolate and vanilla, and rolls of green cloth and pale blue cotton which the Indians had woven in Peru, in some sandy village near the sea, in sight of the pelicans and the penguins. In addition to all these things, they usually had a number of the personal possessions of those they had taken on the seas. Lying in the chests for subsequent division were swords, silver-mounted pistols, daggers chased and inlaid, watches from Spain, necklaces of uncut jewels, rings and bangles, heavy carved furniture, "cases of bottles" of delicately cut green glass, containing cordials distilled of precious mints, with packets of emeralds from Brazil, bezoar stones from Patagonia, paintings from Spain, and medicinal gums from Nicaragua. All these things were divided by lot at the main-mast as soon as the anchor held. As the ship, or ships, neared port, her men hung colours out—any colours they could find—to make their vessel gay. A cup of drink was taken as they sailed slowly home to moorings, and as they drank they fired off the cannon, "bullets and all," again and yet again, rejoicing as the bullets struck the water. Up in the bay, the ships in the harbour answered with salutes of cannon; flags were dipped and hoisted in salute; and so the anchor dropped in some safe reach, and the division of the spoil began.

After the division of the spoil in the beautiful Port[133] Royal harbour, in sight of the palm-trees and the fort with the colours flying, the buccaneers packed their gear, and dropped over the side into a boat. They were pulled ashore by some grinning black man with a scarlet scarf about his head and the brand of a hot iron on his shoulders. At the jetty end, where the Indians lounged at their tobacco and the fishermen's canoas rocked, the sunburnt pirates put ashore. Among the noisy company which always gathers on a pier they met with their companions. A sort of Roman triumph followed, as the "happily returned" lounged swaggeringly towards the taverns. Eager hands helped them to carry in their plunder. In a few minutes the gang was entering the tavern, the long, cool room with barrels round the walls, where there were benches and a table and an old blind fiddler jerking his elbow at a jig. Noisily the party ranged about the table, and sat themselves upon the benches, while the drawers, or potboys, in their shirts, drew near to take the orders. I wonder if the reader has ever heard a sailor in the like circumstance, five minutes after he has touched his pay, address a company of parasites in an inn with the question: "What's it going to be?"

After the settlement of Jamaica by the English, the buccaneers became more enterprising. One buccaneer captain, the most remarkable of all of them, a man named Mansvelt, probably a Dutchman from Curaçoa, attempted to found a pirate settlement upon the island of Santa Katalina, or Old Providence. Mansvelt was a fortunate sea-captain, with considerable charm of manner. He was popular with the buccaneers, and had a name among them, for he was the first of them to cross the isthmus and to sail the South Sea. His South-Sea cruise had come to little, for provisions ran short, and his company had been too small to attempt a Spanish town. He had, therefore, retreated to the North Sea to his ships,[134] and had then gone cruising northward along the Nicaragua coast as far as the Blewfields River. From this point he stood away to the island of Santa Katalina, or Old Providence—an island about six miles long, with an excellent harbour, which, he thought, might easily be fortified. A smaller island lies directly to the north of it, separated from it by a narrow channel of the sea. Twenty years before his visit it had been the haunt of an old captain of the name of Blewfields, who had made it his base while his men went logwood cutting on the mainland. Blewfields was now dead, either of rum or war, and the Spaniards had settled there, and had built themselves a fort or castle to command the harbour. Having examined the place, Mansvelt sailed away to Jamaica to equip a fleet to take it. He saw that the golden times which the buccaneers were then enjoying could not last for ever, and that their occupation might be wrecked by a single ill-considered treaty, dated from St James's or the Court of France. He thought that the islands should be seized as a general rendezvous for folk of that way of life. With a little trouble the harbour could be made impregnable. The land was good, and suited for the growing of maize or tobacco—the two products most in demand among them. The islands were near the Main, being only thirty-five leagues from the Chagres River, the stream from which the golden harvest floated from the cities of the south. They were close to the coast of Nicaragua, where the logwood grew in clumps, waiting for the axes of the lumbermen. With the islands in their hands, the buccaneers could drive the Spaniards off the isthmus—or so Mansvelt thought. It would at anyrate have been an easy matter for them to have wrecked the trade routes from Panama to Porto Bello, and from Porto Bello to Vera Cruz.

While Mansvelt lay at Port Royal, scraping and tallow[135]ing his ships, getting beef salted and boucanned, and drumming up his men from the taverns, a Welshman, of the name of Henry Morgan, came sailing up to moorings with half-a-dozen captured merchantmen. But a few weeks before, he had come home from a cruise with a little money in his pockets. He had clubbed together with some shipmates, and had purchased a small ship with the common fund. She was but meanly equipped, yet her first cruise to the westward, on the coast of Campeachy, was singularly lucky. Mansvelt at once saw his opportunity to win recruits. A captain so fortunate as Morgan would be sure to attract followers, for the buccaneers asked that their captains should be valorous and lucky. For other qualities, such as prudence and forethought, they did not particularly care. Mansvelt at once went aboard Morgan's ship to drink a cup of sack with him in the cabin. He asked him to act as vice-admiral to the fleet he was then equipping for Santa Katalina. To this Henry Morgan very readily consented, for he judged that a great company would be able to achieve great things. In a few days, the two set sail together from Port Royal, with a fleet of fifteen ships, manned by 500 buccaneers, many of whom were French and Dutch.

As soon as they arrived at Santa Katalina, they anchored, and sent their men ashore with some heavy guns. The Spanish garrison was strong, and the fortress well situated, but in a few days they forced it to surrender. They then crossed by a bridge of boats to the lesser island to the north, where they ravaged the plantations for fresh supplies. Having blown up all the fortifications save the castle, they sent the Spanish prisoners aboard the ships. They then chose out 100 trusty men to keep the island for them. They left these on the island, under the command of a Frenchman of the name of Le[136] Sieur Simon. They also left the Spanish slaves behind, to work the plantations, and to grow maize and sweet potatoes for the future victualling of the fleet. Mansvelt then sailed away towards Porto Bello, near which city he put his prisoners ashore. He cruised to the eastward for some weeks, snapping up provision ships and little trading vessels; but he learned that the Governor of Panama, a determined and very gallant soldier, was fitting out an army to encounter him, should he attempt to land. The news may have been false, but it showed the buccaneers that they were known to be upon the coast, and that their raid up "the river of Colla" to "rob and pillage" the little town of Nata, on the Bay of Panama, would be fruitless. The Spanish residents of little towns like Nata buried all their gold and silver, and then fled into the woods when rumours of the pirates came to them. To attack such a town some weeks after the townsfolk had received warning of their intentions would have been worse than useless.

Mansvelt, therefore, returned to Santa Katalina to see how the colony had prospered while he had been at sea. He found that Le Sieur Simon had put the harbour "in a very good posture of defence," having built a couple of batteries to command the anchorage. In these he had mounted his cannon upon platforms of plank, with due munitions of cannon-balls and powder. On the little island to the north he had laid out plantations of maize, sweet potatoes, plantains, and tobacco. The first-fruits of these green fields were now ripe, and "sufficient to revictual the whole fleet with provisions and fruits."

Mansvelt was so well satisfied with the prospects of the colony that he determined to hurry back to Jamaica to beg recruits and recognition from the English Governor. The islands had belonged to English subjects in the past, and of right belonged to England still. However, the[137] Jamaican Governor disliked the scheme. He feared that by lending his support he would incur the wrath of the English Government, while he could not weaken his position in Jamaica by sending soldiers from his garrison. Mansvelt, "seeing the unwillingness" of this un-English Governor, at once made sail for Tortuga, where he hoped the French might be less squeamish. He dropped anchor, in the channel between Tortuga and Hispaniola early in the summer of 1665. He seems to have gone ashore to see the French authorities. Perhaps he drank too strong a punch of rum and sugar—a drink very prejudicial in such a climate to one not used to it. Perhaps he took the yellow fever, or the coast cramp; the fact cannot now be known. At any rate he sickened, and died there, "before he could accomplish his desires"—"all things hereby remaining in suspense." One account, based on the hearsay of a sea-captain, says that Mansvelt was taken by the Spaniards, and brought to Porto Bello, and there put to death by the troops.

Le Sieur Simon remained at his post, hoeing his tobacco plants, and sending detachments to the Main to kill manatee, or to cut logwood. He looked out anxiously for Mansvelt's ships, for he had not men enough to stand a siege, and greatly feared that the Spaniards would attack him. While he stayed in this perplexity, wondering why he did not hear from Mansvelt, he received a letter from Don John Perez de Guzman, the Spanish captain-general, who bade him "surrender the island to his Catholic Majesty," on pain of severe punishment. To this Le Sieur Simon made no answer, for he hoped that Mansvelt's fleet would soon be in those waters to deliver him from danger. Don John, who was a very energetic captain-general, determined to retake the place. He left his residence at Panama, and crossed the isthmus to Porto Bello, where he found a ship, called the St Vincent, "that belonged to the Company of[138] the Negroes" (the Isthmian company of slavers), lying at anchor, waiting for a freight. We are told that she was a good ship, "well mounted with guns." He provisioned her for the sea, and manned her with about 400 men, mostly soldiers from the Porto Bello forts. Among the company were seven master gunners and "twelve Indians very dexterous at shooting with bows and arrows." The city of Cartagena furnished other ships and men, bringing the squadron to a total of four vessels and 500 men-at-arms. With this force the Spanish commander arrived off Santa Katalina, coming to anchor in the port there on the evening of a windy day, the 10th of August 1665. As they dropped anchor they displayed their colours. As soon as the yellow silk blew clear, Le Sieur Simon discharged "three guns with bullets" at the ships, "the which were soon answered in the same coin." The Spaniard then sent a boat ashore to summon the garrison, threatening death to all if the summons were refused. To this Le Sieur Simon replied that the island was a possession of the English Crown, "and that, instead of surrendering it, they preferred to lose their lives." As more than a fourth of the little garrison was at that time hunting on the Main, or at sea, the answer was heroic. Three days later, some negroes swam off to the ships to tell the Spaniards of the garrison's weakness. After two more days of council, the boats were lowered from the ships, and manned with soldiers. The guns on the gun-decks were loaded, and trained. The drums beat to quarters both on the ships and in the batteries. Under the cover of the warship's guns, the boats shoved off towards the landing-place, receiving a furious fire from the buccaneers. The "weather was very calm and clear," so that the smoke from the guns did not blow away fast enough to allow the buccaneers to aim at the boats. The landing force formed into three parties, two of which[139] attacked the flanks, and the third the centre. The battle was very furious, though the buccaneers were outnumbered and had no chance of victory. They ran short of cannon-balls before they surrendered, but they made shift for a time with small shot and scraps of iron, "also the organs of the church," of which they fired "threescore pipes" at a shot. The fighting lasted most of the day, for it was not to the advantage of the Spaniards to come to push of pike. Towards sunset the buccaneers were beaten from their guns. They fought in the open for a few minutes, round "the gate called Costadura," but the Spaniards surrounded them, and they were forced to lay down their arms. The Spanish colours were set up, and two poor Spaniards who had joined the buccaneers were shot to death upon the Plaza. The English prisoners were sent aboard the ships, and carried into Porto Bello, where they were put to the building of a fortress—the Iron Castle, a place of great strength, which later on the English blew to pieces. Some of the men were sent to Panama "to work in the castle of St Jerome"—a wonderful, great castle, which was burned at the sack of Panama almost before the mortar dried.

While the guns were roaring over Santa Katalina, as Le Sieur Simon rammed his cannon full of organ pipes, Henry Morgan was in lodgings at Port Royal, greatly troubled at the news of Mansvelt's death. He was busily engaged at the time with letters to the merchants of New England. He was endeavouring to get their help towards the fortification of the island he had helped to capture. "His principal intent," writes one who did not love the man, "was to consecrate it as a refuge and sanctuary to the Pirates of those parts," making it "a convenient receptacle or store house of their preys and robberies." It is pleasant to speculate as to the reasons he urged to the devout New England Puritans. He must have chuckled to himself, and[140] shared many a laugh with his clerk, to think that perhaps a Levite, or a Man of God, a deacon, or an elder, would untie the purse-strings of the sealed if he did but agonise about the Spanish Inquisition with sufficient earthquake and eclipse. He heard of the loss of the island before the answers came to him, and the news, of course, "put him upon new designs," though he did not abandon the scheme in its entirety. He had his little fleet at anchor in the harbour, gradually fitting for the sea, and his own ship was ready. Having received his commission from the Governor, he gave his captains orders to meet him on the Cuban coast, at one of the many inlets affording safe anchorage. Here, after several weeks of cruising, he was joined by "a fleet of twelve sail," some of them of several hundred tons. These were manned by 700 fighting men, part French, part English.

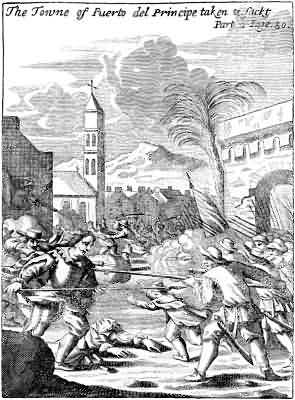

At the council of war aboard the admiral's ship, it was suggested that so large a company should venture on Havana, which city, they thought, might easily be taken, "especially if they could but take a few of the ecclesiastics." Some of the pirates had been prisoners in the Havana, and knew that a town of 30,000 inhabitants would hardly yield to 700 men, however desperate. "Nothing of consequence could be done there," they pronounced, even with ecclesiastics, "unless with fifteen hundred men." One of the pirates then suggested the town of Puerto del Principe, an inland town surrounded by tobacco fields, at some distance from the sea. It did a thriving trade with the Havana; and he who suggested that it should be sacked, affirmed upon his honour, like Boult over Maria, that it never yet "was sacked by any Pirates." Towards this virginal rich town the buccaneers proceeded, keeping close along the coast until they made the anchorage of Santa Maria. Here they dropped anchor for the night.[141]

When the men were making merry over the punch, as they cleaned their arms, and packed their satchels, a Spanish prisoner "who had overheard their discourse, while they thought he did not understand the English tongue," slipped through a port-hole to the sea, and swam ashore. By some miracle he escaped the ground sharks, and contrived to get to Puerto del Principe some hours before the pirates left their ships. The Governor of the town, to whom he told his story, at once raised all his forces, "both freemen and slaves," to prejudice the enemy when he attacked. The forest ways were blocked with timber baulks, and several ambuscades were laid, with cannon in them, "to play upon them on their march." In all, he raised and armed 800 men, whom he disposed in order, either in the jungle at the ambuscades or in a wide expanse of grass which surrounded the town.

In due course Morgan sent his men ashore, and marched them through the wood towards the town. They found the woodland trackways blocked by the timber baulks, so they made a detour, hacking paths for themselves with their machetes, until they got clear of the wood. When they got out of the jungle they found themselves on an immense green field, covered with thick grass, which bowed and shivered in the wind. A few pale cattle grazed here and there on the savannah; a few birds piped and twittered in the sunshine. In front of them, at some little distance, was the town they had come to pillage. It lay open to them—a cluster of houses, none of them very large, with warehouses and tobacco drying-rooms and churches with bells in them. Outside the town, some of them lying down, some standing so as to get a view of the enemy, were the planters and townsfolk, with their pikes and muskets, waiting for the battle to begin. Right in the pirates' front was a troop of horsemen armed with lances, swords, and pistols, drawn up in very good order, and[142] ready to advance. The pirates on their coming from the wood formed into a semicircle or half-moon shape, the bow outwards, the horns curving to prevent the cavalry from taking them in flank. They had drums and colours in their ranks. The drums beat out a bravery, the colours were displayed. The men halted for a moment to get their breath and to reprime their guns. Then they advanced slowly, to the drubbing of the drums, just as the Spanish horsemen trotted forward. As the Spaniards sounded the charge, the buccaneers fired a volley of bullets at them, which brought a number of cavaliers out of their saddles. Those horsemen who escaped the bullets dashed down upon the line, and fired their pistols at close quarters, afterwards wheeling round, and galloping back to reform. They charged again and again, "like valiant and courageous soldiers," but at every charge the pirates stood firm, and withered them with file-firing. As they retired after each rush, the marksmen in the ranks picked them off one by one, killing the Governor, in his plumed hat, and strewing the grass with corpses. They also manœuvred during this skirmish so as to cut off the horsemen from the town. After four hours of battle the cavalry were broken and defeated, and in no heart to fight further. They made a last charge on their blown horses, but their ranks went to pieces at the muzzles of the pirates' guns. They broke towards the cover of the woods, but the pirates charged them as they ran, and cut them down without pity. Then the drums beat out a bravery, and the pirates rushed the town in the face of a smart fire. The Spaniards fought in the streets, while some fired from the roofs and upper windows. So hot was the tussle that the pirates had to fight from house to house. The townsmen did not cease their fire, till the pirates were gathering wood to burn the town, in despair of taking it.

As soon as the firing ceased, the townsfolk were driven[143] to the churches, and there imprisoned under sentinels. Afterwards the pirates "searched the whole country round about the town, bringing in day by day many goods and prisoners, with much provision." The wine and spirits of the townsfolk were set on tap, and "with this they fell to banqueting among themselves, and making great cheer after their customary way." They feasted so merrily that they forgot their prisoners, "whereby the greatest part perished." Those who did not perish were examined in the Plaza, "to make them confess where they had hidden their goods." Those who would not tell where they had buried their gold were tortured very barbarously by burning matches, twisted cords, or lighted palm leaves. Finally, the starving wretches were ordered to find ransoms, "else they should be all transported to Jamaica" to be sold as slaves. The town was also laid under a heavy contribution, without which, they said, "they would turn every house into ashes."

It happened that, at this juncture, some buccaneers, who were raiding in the woods, made prisoner a negro carrying letters from the Governor of the Havana. The letters were written to the citizens, telling them to delay the payment of their ransoms as long as possible, for that he was fitting out some soldiers to relieve them. The letters warned Henry Morgan that he had better be away with the treasure he had found. He gave order for the plunder to be sent aboard in the carts of the townsfolk. He then called up the prisoners, and told them very sharply that their ransoms must be paid the next day, "forasmuch as he would not wait one moment longer, but reduce the whole town to ashes, in case they failed to perform the sum he demanded." As it was plainly impossible for the townsfolk to produce their ransoms at this short notice he graciously relieved their misery by adding that he would be contented with 500 beeves, "together with[144] sufficient salt wherewith to salt them." He insisted that the cattle should be ready for him by the next morning, and that the Spaniards should deliver them upon the beach, where they could be shifted to the ships without delay. Having made these terms, he marched his men away towards the sea, taking with him six of the principal prisoners "as pledges of what he intended." Early the next morning the beach of Santa Maria bay was thronged with cattle in charge of negroes and planters. Some of the oxen had been yoked to carts to bring the necessary salt. The Spaniards delivered the ransom, and demanded the six hostages. Morgan was by this time in some anxiety for his position. He was eager to set sail before the Havana ships came round the headland, with their guns run out, and matches lit, and all things ready for a fight. He refused to release the prisoners until the vaqueros "had helped his men to kill and salt the beeves." The work of killing and salting was performed "in great haste," lest the Havana ships should come upon them before the beef was shipped. The hides were left upon the sands, there being no time to dry them before sailing. A Spanish cowboy can kill, skin, and cut up a steer in a few minutes. The buccaneers were probably no whit less skilful. By noon the work was done. The beach of Santa Maria was strewn with mangled remnants, over which the seagulls quarrelled. But before Morgan could proceed to sea, he had to quell an uproar which was setting the French and English by the ears. The parties had not come to blows, but the French were clamouring for vengeance with drawn weapons. A French sailor, who was working on the beach, killing and pickling the meat, had been plundered by an Englishman, who "took away the marrowbones he had taken out of the ox." Marrow, "toute chaude," was a favourite dish among these people. The Frenchman could not brook an insult of a kind as hurtful to his dinner as to[145] his sense of honour. He challenged the thief to single combat: swords the weapon, the time then. The buccaneers knocked off their butcher's work to see the fight. As the poor Frenchman turned his back to make him ready, his adversary stabbed him from behind, running him quite through, so that "he suddenly fell dead upon the place." Instantly the beach was in an uproar. The Frenchmen pressed upon the English to attack the murderer and to avenge the death of their fellow. There had been bad blood between the parties ever since they mustered at the quays before the raid began. The quarrel now raging was an excuse to both sides. Morgan walked between the angry groups, telling them to put up their swords. At a word from him, the murderer was seized, set in irons, and sent aboard an English ship. Morgan then seems to have made a little speech to pacify the rioters, telling the French that the man should be hanged ("hanged immediately," as they said of Admiral Byng) as soon as the ships had anchored in Port Royal bay. To the English, he said that the criminal was worthy of punishment, "for although it was permitted him to challenge his adversary, yet it was not lawful to kill him treacherously, as he did." After a good deal of muttering, the mutineers returned aboard their ships, carrying with them the last of the newly salted beef. The hostages were freed, a gun was fired from the admiral's ship, and the fleet hove up their anchors, and sailed away from Cuba, to some small sandy quay with a spring of water in it, where the division of the plunder could be made. The plunder was heaped together in a single pile. It was valued by the captains, who knew by long experience what such goods would fetch in the Jamaican towns.

To the "resentment and grief" of all the 700 men these valuers could not bring the total up to 50,000 pieces of eight—say £12,000—"in money and goods."[146] All hands were disgusted at "such a small booty, which was not sufficient to pay their debts at Jamaica." Some cursed their fortune; others cursed their captain. It does not seem to have occurred to them to blame themselves for talking business before their Spanish prisoners. Morgan told them to "think upon some other enterprize," for the ships were fit to keep the sea, and well provisioned. It would be an easy matter, he told them, to attack some town upon the Main "before they returned home," so that they should have a little money for the taverns, to buy them rum with, at the end of the cruise. But the French were still sore about the murder of their man: they raised objections to every scheme the English buccaneers proposed. Each proposition was received contemptuously, with angry bickerings and mutterings. At last the French captains intimated that they desired to part company. Captain Morgan endeavoured to dissuade them from this resolution by using every flattery his adroit nature could suggest. Finding that they would not listen to him, even though he swore by his honour that the murderer, then in chains, should be hanged as soon as they reached home, he brought out wine and glasses, and drank to their good fortune. The booty was then shared up among the adventurers. The Frenchmen got their shares aboard, and set sail for Tortuga to the sound of a salute of guns. The English held on for Port Royal, in great "resentment and grief." When they arrived there they caused the murderer to be hanged upon a gallows, which, we are told, "was all the satisfaction the French Pirates could expect."[147]

Note.—If we may believe Morgan's statement to Sir T. Modyford, then Governor of Jamaica, he brought with him from Cuba reliable evidence that the Spaniards were planning an attack upon that colony (see State Papers: West Indies and Colonial Series). If the statements of his prisoners were correct, the subsequent piratical raid upon the Main had some justification. Had the Spaniards matured their plans, and pushed the attack home, it is probable that we should have lost our West Indian possessions.

Authorities.—A. O. Exquemeling: "Bucaniers of America," eds. 1684-5 and 1699. Cal. State Papers: "West Indies."

[15] Dampier and Exquemeling.