On the Spanish Main, by John Masefield

CHAPTER X

THE SACK OF PORTO BELLO

The Gulf of Maracaibo—Morgan's escape from the Spaniards

It was a melancholy home-coming. The men had little more than ten pounds apiece to spend in jollity. The merchants who enjoyed their custom were of those kinds least anxious to give credit. The ten pounds were but sufficient to stimulate desire. They did not allow the jolly mariner to enjoy himself with any thoroughness. In a day or two, the buccaneers were at the end of their gold, and had to haunt the street corners, within scent of the rum casks, thinking sadly of the pleasant liquor they could not afford to drink. Henry Morgan took this occasion to recruit for a new enterprise. He went ashore among the drinking-houses, telling all he met of golden towns he meant to capture. He always "communicated vigour with his words," for, being a Welshman, he had a certain fervour of address, not necessarily sincere, which touched his simplest phrase with passion. In a day or two, after a little talk and a little treating, every disconsolate drunkard in the town was "persuaded by his reasons, that the sole execution of his orders, would be a certain means of obtaining great riches." This persuasion, the writer adds, "had such influence upon their minds, that with inimitable courage they all resolved to follow him." Even "a certain Pirate of Campeachy," a shipowner of considerable repute, resolved to follow Morgan "to seek new fortunes and greater advantages than he had found before." The French might hold aloof,[149] they all declared, but an Englishman was still the equal of a Spaniard; while after all a short life and a merry one was better than work ashore or being a parson. With this crude philosophy, they went aboard again to the decks they had so lately left. The Campeachy pirate brought in a ship or two, and some large canoas. In all they had a fleet of nine sail, manned by "four hundred and three score military men." With this force Captain Morgan sailed for Costa Rica.

When they came within the sight of land, a council was called, to which the captains of the vessels went. Morgan told them that he meant to plunder Porto Bello by a night attack, "being resolved" to sack the place, "not the least corner escaping his diligence." He added that the scheme had been held secret, so that "it would not fail to succeed well." Besides, he thought it likely that a city of such strength would be unprepared for any sudden attack. The captains were staggered by this resolution, for they thought themselves too weak "to assault so strong and great a city." To this the plucky Welshman answered: "If our number is small, our hearts are great. And the fewer persons we are, the more union and better shares we shall have in the spoil." This answer, with the thought of "those vast riches they promised themselves," convinced the captains that the town could be attempted. It was a "dangerous voyage and bold assault" but Morgan had been lucky in the past, and the luck might still be with him. He knew the Porto Bello country, having been there with a party (perhaps Mansvelt's party) some years before. At any rate the ships would be at hand in the event of a repulse.

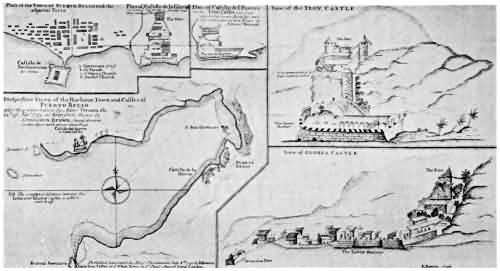

It was something of a hazard, for the Spanish garrison was formed of all the desperate criminals the colonial police could catch. These men made excellent soldiers, for after a battle they were given the plunder of the men[150] they had killed. Then Panama, with its great garrison, was perilously near at hand, being barely sixty miles away, or two days' journey. Lastly, the town was strongly fortified, with castles guarding it at all points. The garrison was comparatively small, mustering about three companies of foot. To these, however, the buccaneers had to add 300 townsfolk capable of bearing arms. Following John Exquemeling's plan, we add a brief description of this famous town, to help the reader to form a mental picture of it.

Porto Bello stands on the south-eastern side of a fine bay, "in the province of Costa Rica." At the time when Morgan captured it (in June 1668) it was one of the strongest cities in the possession of the King of Spain. It was neglected until 1584, when a royal mandate caused the traders of Nombre de Dios to migrate thither. It then became the port of the galleons,[16] where the treasures of the south were shipped for Spain. The city which Morgan sacked was built upon a strip of level ground planted with fruit-trees, at a little distance from the sea, but within a few yards of the bay. The westward half of the town was very stately, being graced with fine stone churches and the residence of the lieutenant-general. Most of the merchants' dwellings (and of these there may have been 100) were built of cedar wood. Some were of stone, a thing unusual in the Indies, and some were partly stone, with wooden upper storeys. There was a fine stone convent peopled by Sisters of Mercy, and a dirty, ruinous old hospital for "the sick men belonging to the ships of war." On the shore there was a quay, backed by a long stone custom-house. The main street ran along the shore behind this custom-house, with cross-streets leading to the two great squares. The eastward half of the city, through which the road to Panama ran, was called Guinea; for there the slaves and negroes used to[151] live, in huts and cottages of sugar-cane and palm leaves. There, too, was the slave mart, to which the cargoes of the Guinea ships were brought. A little river of clear water divided the two halves of the town. Another little river, bridged in two places, ran between the town and Castle Gloria. The place was strongly fortified. Ships entering the bay had to pass close to the "Iron Castle," built upon the western point. Directly they stood away towards the town they were exposed to the guns of Castle Gloria and Fort Jeronimo—the latter a strong castle built upon a sandbank off the Guinea town. The constant population was not large, though probably 300 white men lived there all the year round, in addition to the Spanish garrison. The native quarter was generally inhabited by several hundred negroes and mulattoes. When the galleons arrived there, and for some weeks before, the town was populous with merchants, who came across from Panama to buy and sell. Tents were pitched in the Grand Plaza, in front of the Governor's house, for the protection of perishable goods, like Jesuits'-bark. Gold and silver bars became as common to the sight as pebbles. Droves of mules came daily in from Panama, and ships arrived daily from all the seaports in the Indies. As soon as the galleons sailed for Spain, the city emptied as rapidly as it had filled. It was too unhealthy a place for white folk, who continued there "no longer than was needful to acquire a fortune."

Indeed, Porto Bello was one of the most pestilential cities ever built, "by reason of the unhealthiness of the Air, occasioned by certain Vapours that exhale from the Mountains." It was excessively hot, for it lay (as it still lies) in a well, surrounded by hills, "without any intervals to admit the refreshing gales." It was less marshy than Nombre de Dios, but "the sea, when it ebbs, leaves a vast quantity of black, stinking mud, from whence there exhales[152] an intolerable noisome vapour." At every fair-time "a kind of pestilential fever" raged, so that at least 400 folk were buried there annually during the five or six weeks of the market. The complaint may have been yellow fever; (perhaps the cholera), perhaps pernicious fever, aggravated by the dirty habits of the thousands then packed within the town. The mortality was especially heavy among the sailors who worked aboard the galleons, hoisting in or out the bales of merchandise. These mariners drank brandy very freely "to recruit their spirits," and in other ways exposed themselves to the infection. The drinking water of the place was "too fine and active for the stomachs of the inhabitants," who died of dysentery if they presumed to drink of it. The town smoked in a continual steam of heat, unrelieved even by the torrents of rain which fall there every day. The woods are infested with poisonous snakes, and abound in a sort of large toad or frog which crawls into the city after rains. The tigers "often make incursions into the street," as at Nombre de Dios, to carry off children and domestic animals. There was good fishing in the bay, and the land was fertile "beyond wonder," so that the cost of living there, in the tiempo muerto, was very small. There is a hill behind the town called the Capiro, about which the streamers of the clouds wreathe whenever rain is coming. The town was taken by Sir Francis Drake in 1595, by Captain Parker in 1601, by Morgan in 1668, by Coxon in 1679, and by Admiral Vernon in 1740.

Having told his plans, the admiral bade his men make ready. During the afternoon he held towards the west of Porto Bello, at some distance from the land. The coast up to the Chagres River, and for some miles beyond, is low, so that there was not much risk of the ships being sighted from the shore. As it grew darker, he edged into the land, arriving "in the dusk of the evening" at a place[153] called Puerto de Naos, or Port of Ships, a bay midway between Porto Bello and the Chagres, and about ten leagues from either place.

They sailed westward up the coast for a little distance to a place called Puerto Pontin, where they anchored. Here the pirates got their boats out, and took to the oars, "leaving in the ships only a few men to keep them, and conduct them the next day to the port." By the light of lamps and battle lanterns the boats rowed on through the darkness, till at midnight they had came to a station called Estera longa Lemos, a river-mouth a few miles from Porto Bello, "where they all went on shore." After priming their muskets, they set forth towards the city, under the guidance of an English buccaneer, who had been a prisoner at Porto Bello but a little while before. When they were within a mile or two of the town, they sent this Englishmen with three or four companions to take a solitary sentry posted at the city outskirts. If they could not take him, they were to kill him, but without giving the alarm to the inhabitants. By creeping quietly behind him, the party took the sentry, "with such cunning that he had no time to give warning with his musket, or make any other noise." A knife point pressing on his spine, and a gag of wood across his tongue, warned him to attempt no outcry. Some rope-yarn was passed about his wrists, and in this condition he was dragged to Captain Morgan. As soon as he was in the admiral's presence, he was questioned as to the number of soldiers then in the forts, "with many other circumstances." It must have been a most uncomfortable trial, for "after every question, they made him a thousand menaces to kill him, in case he declared not the truth." When they had examined him to their satisfaction, they recommenced their march, "carrying always the said sentry bound before them." Another mile brought them to an outlying fortress, which[154] was built apparently between Porto Bello and the sea, to protect the coast road and a few outlying plantations. It was not yet light, so the pirates crept about the fort unseen, "so that no person could get either in or out." When they had taken up their ground, Morgan bade the captured sentry hail the garrison, charging them to surrender on pain of being cut to pieces. The garrison at once ran to their weapons, and opened a fierce fire on the unseen enemy, thus giving warning to the city that the pirates were attacking. Before they could reload, the buccaneers, "the noble Sparks of Venus," stormed in among them, taking them in their confusion, hardly knowing what was toward. Morgan was furious that the Spaniards had not surrendered at discretion on his challenge. The pirates were flushed with the excitement of the charge. Someone proposed that they "should be as good as their words, in putting the Spaniards to the sword, thereby to strike a terror into the rest of the city." They hustled the Spanish soldiers "into one room," officers and men together. The cellars of the fort were filled with powder barrels. Some ruffian took a handful of the powder, and spilled a train along the ground, telling his comrades to stand clear. His mates ran from the building applauding his device. In another moment the pirate blew upon his musket match to make the end red, and fired the train he had laid, "and blew up the whole castle into the air, with all the Spaniards that were within." "Much the better way of the two," says one of the chroniclers, who saw the explosion.

"This being done," says the calm historian, "they pursued the course of their victory" into the town. By this time, the streets were thronged with shrieking townsfolk. Men ran hither and thither with their poor belongings. Many flung their gold and jewels into wells and cisterns, or stamped them underground, "to excuse their[155] being totally robbed." The bells were set clanging in the belfries; while, to increase the confusion, the Governor rode into the streets, calling on the citizens to rally and stand firm. As the dreadful panic did not cease, he rode out of the mob to one of the castles (Castle Gloria), where the troops were under arms. It was now nearly daybreak, or light enough for them to see their enemy. As the pirates came in sight among the fruit-trees, the Governor trained his heavy guns upon them, and opened a smart fire. Some lesser castles, or the outlying works of Castle Gloria, which formed the outer defences of the town, followed his example; nor could the pirates silence them. One party of buccaneers crept round the fortifications to the town, where they attacked the monastery and the convent, breaking into both with little trouble, and capturing a number of monks and nuns. With these they retired to the pirates' lines.

For several hours, the pirates got no farther, though the fire did not slacken on either side. The pirates lay among the scrub, hidden in the bushes, in little knots of two and three. They watched the castle embrasures after each discharge of cannon, for the Spaniards could not reload without exposing themselves as they sponged or rammed. Directly a Spaniard appeared, he was picked off from the bushes with such precision that they lost "one or two men every time they charged each gun anew." The losses on the English side were fully as severe; for, sheltered though they were, the buccaneers lost heavily. The lying still under a hot sun was galling to the pirates' temper. They made several attempts to storm, but failed in each attempt owing to the extreme gallantry of the defence. Towards noon they made a furious attack, carrying fireballs, or cans filled with powder and resin, in their hands "designing, if possible, to burn the doors of the castle." As they came beneath the walls, the Spaniards rolled[156] down stones upon them, with "earthen pots full of powder" and iron shells filled full of chain-shot, "which forced them to desist from that attempt." Morgan's party was driven back with heavy loss. It seemed to Morgan at this crisis that the victory was with the Spanish. He wavered for some minutes, uncertain whether to call off his men. "Many faint and calm meditations came into his mind" seeing so many of his best hands dead and the Spanish fire still so furious. As he debated "he was suddenly animated to continue the assault, by seeing the English colours put forth at one of the lesser castles, then entered by his men." A few minutes later the conquerors came swaggering up to join him, "proclaiming victory with loud shouts of joy."

Leaving his musketeers to fire at the Spanish gunners, Morgan turned aside to reconnoitre. Making the capture of the lesser fort his excuse, he sent a trumpet, with a white flag, to summon the main castle, where the Governor had flown the Spanish standard. While the herald was gone upon his errand, Morgan set some buccaneers to make a dozen scaling ladders, "so broad that three or four men at once might ascend by them." By the time they were finished, the trumpeter returned, bearing the Governor's answer that "he would never surrender himself alive." When the message had been given, Captain Morgan formed his soldiers into companies, and bade the monks and nuns whom he had taken, to place the ladders against the walls of the chief castle. He thought that the Spanish Governor would hardly shoot down these religious persons, even though they bore the ladders for the scaling parties. In this he was very much mistaken. The Governor was there to hold the castle for his Catholic Majesty, and, like "a brave and courageous soldier," he "refused not to use his utmost endeavours to destroy whoever came near the walls." As the wretched monks and[157] nuns came tottering forward with the ladders, they begged of him, "by all the Saints of Heaven," to haul his colours down, to the saving of their lives. Behind them were the pirates, pricking them forward with their pikes and knives. In front of them were the cannon of their friends, so near that they could see the matches burning in the hands of the gunners. "They ceased not to cry to him," says the narrative; but they could not "prevail with the obstinacy and fierceness that had possessed the Governor's mind"—"the Governor valuing his honour before the lives of the Mass-mumblers." As they drew near to the walls, they quickened their steps, hoping, no doubt, to get below the cannon muzzles out of range. When they were but a few yards from the walls, the cannon fired at them, while the soldiers pelted them with a fiery hail of hand-grenades. "Many of the religious men and nuns were killed before they could fix the ladders"; in fact, the poor folk were butchered there in heaps, before the ladders caught against the parapet. Directly the ladders held, the pirates stormed up with a shout, in great swarms, like a ship's crew going aloft to make the sails fast. They had "fireballs in their hands and earthen pots full of powder," which "they kindled and cast in among the Spaniards" from the summits of the walls. In the midst of the smoke and flame which filled the fort the Spanish Governor stood fighting gallantly. His wife and child were present in that house of death, among the blood and smell, trying to urge him to surrender. The men were running from their guns, and the hand-grenades were bursting all about him, but this Spanish Governor refused to leave his post. The buccaneers who came about him called upon him to surrender, but he answered that he would rather die like a brave soldier than be hanged as a coward for deserting his command, "so[158] that they were enforc'd to kill him, nothwithstanding the cries of his Wife and Daughter."

The sun was setting over Iron Castle before the firing came to an end with the capture of the Castle Gloria. The pirates used the last of the light for the securing of their many prisoners. They drove them to some dungeon in the castle, where they shut them up under a guard. The wounded "were put into a certain apartment by itself," without medicaments or doctors, "to the intent their own complaints might be the cure of their diseases." In the dungeons of the castle's lower battery they found eleven English prisoners chained hand and foot. They were the survivors of the garrison of Providence, which the Spaniards treacherously took two years before. Their backs were scarred with many floggings, for they had been forced to work like slaves at the laying of the quay piles in the hot sun, under Spanish overseers. They were released at once, and tenderly treated, nor were they denied a share of the plunder of the town.

"Having finish'd this Jobb" the pirates sought out the "recreations of Heroick toil." "They fell to eating and drinking" of the provisions stored within the city, "committing in both these things all manner of debauchery and excess." They tapped the casks of wine and brandy, and "drank about" till they were roaring drunk. In this condition they ran about the town, like cowboys on a spree, "and never examined whether it were Adultery or Fornication which they committed." By midnight they were in such a state of drunken disorder that "if there had been found only fifty courageous men, they might easily have retaken the City, and killed the Pirats." The next day they gathered plunder, partly by routing through the houses, partly by torturing the townsfolk. They seem to have been no less brutal here than they had been in Cuba, though the Porto Bello houses yielded[159] a more golden spoil than had been won at Puerto Principe. They racked one or two poor men until they died. Others they slowly cut to pieces, or treated to the punishment called "woolding," by which the eyes were forced from their sockets under the pressure of a twisted cord. Some were tortured with burning matches "and such like slight torments." A woman was roasted to death "upon a baking stone"—a sin for which one buccaneer ("as he lay sick") was subsequently sorry.

While they were indulging these barbarities, they drank and swaggered and laid waste. They stayed within the town for fifteen days, sacking it utterly, to the last ryal. They were too drunk and too greedy to care much about the fever, which presently attacked them, and killed a number, as they lay in drunken stupor in the kennels. News of their riot being brought across the isthmus, the Governor of Panama resolved to send a troop of soldiers, to attempt to retake the city, but he had great difficulty in equipping a sufficient force. Before his men were fit to march, some messengers came in from the imprisoned townsfolk, bringing word from Captain Morgan that he wanted a ransom for the city, "or else he would by fire consume it to ashes." The pirate ships were by this time lying off the town, in Porto Bello bay. They were taking in fresh victuals for the passage home. The ransom asked was 100,000 pieces of eight, or £25,000. If it had not been paid the pirates could have put their threat in force without the slightest trouble. Morgan made all ready to ensure his retreat in the event of an attack from Panama. He placed an outpost of 100 "well-arm'd" men in a narrow part of the passage over the isthmus. All the plunder of the town was sent on board the ships. In this condition he awaited the answer of the President.[160]

As soon as that soldier had sufficient musketeers in arms, he marched them across the isthmus to relieve the city. They attempted the pass which Morgan had secured, but lost very heavily in the attempt. The buccaneers charged, and completely routed them, driving back the entire company along the road to Panama. The President had "to retire for that time," but he sent a blustering note to Captain Morgan, threatening him and his with death "when he should take them, as he hoped soon to do." To this Morgan replied that he would not deliver the castles till he had the money, and that if the money did not come, the castles should be blown to pieces, with the prisoners inside them. We are told that "the Governor of Panama perceived by this answer that no means would serve to mollify the hearts of the Pirates, nor reduce them to reason." He decided to let the townsfolk make what terms they could. In a few days more these wretched folk contrived to scrape together the required sum of money, which they paid over as their ransom.

Before the expedition sailed away, a messenger arrived from Panama with a letter from the Governor to Captain Morgan. It made no attempt to mollify his heart nor to reduce him to reason, but it expressed a wonder at the pirates' success. He asked, as a special favour, that Captain Morgan would send him "some small patterns" of the arms with which the city had been taken. He thought it passing marvellous that a town so strongly fortified should have been won by men without great guns. Morgan treated the messenger to a cup of drink, and gave him a pistol and some leaden bullets "to carry back to the President, his Master." "He desired him to accept that pattern of the arms wherewith he had taken Porto Bello." He requested him to keep them for a twelvemonth, "after which time he promised to come to[161] Panama and fetch them away." The Spaniard returned the gift to Captain Morgan, "giving him thanks for lending him such weapons as he needed not." He also sent a ring of gold, with the warning "not to give himself the trouble of coming to Panama," for "he should not speed so well there" as he had sped at Porto Bello.

"After these transactions" Captain Morgan loosed his top-sail, as a signal to unmoor. His ships were fully victualled for the voyage, and the loot was safely under hatches. As a precaution, he took with him the best brass cannon from the fortress. The iron guns were securely spiked with soft metal nails, which were snapped off flush with the touch-holes. The anchors were weighed to the music of the fiddlers, a salute of guns was fired, and the fleet stood out of Porto Bello bay along the wet, green coast, passing not very far from the fort which they had blown to pieces. In a few days' time they raised the Keys of Cuba, their favourite haven, where "with all quiet and repose" they made their dividend. "They found in ready money two hundred and fifty thousand pieces of eight, besides all other merchandises, as cloth, linen, silks and other goods." The spoil was amicably shared about the mast before a course was shaped for their "common rendezvous"—Port Royal.

A godly person in Jamaica, writing at this juncture in some distress, expressed himself as follows:—"There is not now resident upon this place ten men to every [licensed] house that selleth strong liquors ... besides sugar and rum works that sell without license." When Captain Morgan's ships came flaunting into harbour, with their colours fluttering and the guns thundering salutes, there was a rustle and a stir in the heart of every publican. "All the Tavern doors stood open, as they do at London, on Sundays, in the afternoon." Within those tavern doors, "in all sorts of vices and debauchery," the[162] pirates spent their plunder "with huge prodigality," not caring what might happen on the morrow.

Shortly after the return from Porto Bello, Morgan organised another expedition with which he sailed into the Gulf of Maracaibo. His ships could not proceed far on account of the shallowness of the water, but by placing his men in the canoas he penetrated to the end of the Gulf. On the way he sacked Maracaibo, a town which had been sacked on two previous occasions—the last time by L'Ollonais only a couple of years before. Morgan's men tortured the inhabitants, according to their custom, either by "woolding" them or by placing burning matches between their toes. They then set sail for Gibraltar, a small town strongly fortified, at the south-east corner of the Gulf. The town was empty, for the inhabitants had fled into the hills with "all their goods and riches." But the pirates sent out search parties, who brought in many prisoners. These were examined, with the usual cruelties, being racked, pressed, hung up by the heels, burnt with palm leaves, tied to stakes, suspended by the thumbs and toes, flogged with rattans, or roasted at the camp fires. Some were crucified, and burnt between the fingers as they hung on the crosses; "others had their feet put into the fire."

When they had extracted the last ryal from the sufferers they shipped themselves aboard some Spanish vessels lying in the port. They were probably cedar-built ships, of small tonnage, built at the Gibraltar yards. In these they sailed towards Maracaibo, where they found "a poor distressed old man, who was sick." This old man told them that the Castle de la Barra, which guarded the entrance to the Gulf, had been mounted with great guns and manned by a strong garrison. Outside the channel were three Spanish men-of-war with their guns run out and decks cleared for battle.[163]

The truth of these assertions was confirmed by a scouting party the same day. In order to gain a little time Morgan sent a Spaniard to the admiral of the men-of-war, demanding a ransom "for not putting Maracaibo to the flame." The answer reached him in a day or two, warning him to surrender all his plunder, and telling him that if he did not, he should be destroyed by the sword. There was no immediate cause for haste, because the Spanish admiral could not cross the sandbanks into the Gulf until he had obtained flat-bottomed boats from Caracas. Morgan read the letter to his men "in the market-place of Maracaibo," "both in French and English," and then asked them would they give up all their spoil, and pass unharmed, or fight for its possession. They agreed with one voice to fight, "to the very last drop of blood," rather than surrender the booty they had risked their skins to get. One of the men undertook to rig a fireship to destroy the Spanish admiral's flagship. He proposed to fill her decks with logs of wood "standing with hats and Montera caps," like gunners standing at their guns. At the port-holes they would place other wooden logs to resemble cannon. The ship should then hang out the English colours, the Jack or the red St George's cross, so that the enemy should deem her "one of our best men of war that goes to fight them." The scheme pleased everyone, but there was yet much anxiety among the pirates. Morgan sent another letter to the Spanish admiral, offering to spare Maracaibo without ransom; to release his prisoners, with one half of the captured slaves; and to send home the hostages he brought away from Gibraltar, if he might be granted leave to pass the entry. The Spaniard rejected all these terms, with a curt intimation that, if the pirates did not surrender within two more days, they should be compelled to do so at the sword's point.

Morgan received the Spaniard's answer angrily, re[164]solving to attempt the passage "without surrendering anything." He ordered his men to tie the slaves and prisoners, so that there should be no chance of their attempting to rise. They then rummaged Maracaibo for brimstone, pitch, and tar, with which to make their fireship. They strewed her deck with fireworks and with dried palm leaves soaked in tar. They cut her outworks down, so that the fire might more quickly spread to the enemy's ship at the moment of explosion. They broke open some new gun-ports, in which they placed small drums, "of which the negroes make use." "Finally, the decks were handsomely beset with many pieces of wood dressed up in the shape of men with hats or monteras, and likewise armed with swords, muskets, and bandoliers." The plunder was then divided among the other vessels of the squadron. A guard of musketeers was placed over the prisoners, and the pirates then set sail towards the passage. The fireship went in advance, with orders to fall foul of the Spanish Admiral, a ship of forty guns.

When it grew dark they anchored for the night, with sentinels on each ship keeping vigilant watch. They were close to the entry, almost within shot of the Spaniards, and they half expected to be boarded in the darkness. At dawn they got their anchors, and set sail towards the Spaniards, who at once unmoored, and beat to quarters. In a few minutes the fireship ran into the man-of-war, "and grappled to her sides" with kedges thrown into her shrouds. The Spaniards left their guns, and strove to thrust her away, but the fire spread so rapidly that they could not do so. The flames caught the warship's sails, and ran along her sides with such fury that her men had hardly time to get away from her before she blew her bows out, and went to the bottom. The second ship made no attempt to engage: her crew ran her ashore, and deserted, leaving her bilged in shallow water. As the[165] pirates rowed towards the wreck some of the deserters hurried back to fire her. The third ship struck her colours without fighting.

Seeing their advantage a number of the pirates landed to attack the castle, where the shipwrecked Spaniards were rallying. A great skirmish followed, in which the pirates lost more men than had been lost at Porto Bello. They were driven off with heavy loss, though they continued to annoy the fort with musket fire till the evening. As it grew dark they returned to Maracaibo, leaving one of their ships to watch the fortress and to recover treasure from the sunken flagship. Morgan now wrote to the Spanish admiral, demanding a ransom for the town. The citizens were anxious to get rid of him at any cost, so they compounded with him, seeing that the admiral disdained to treat, for the sum of 20,000 pieces of eight and 500 cattle. The gold was paid, and the cattle duly counted over, killed, and salted; but Morgan did not purpose to release his prisoners until his ship was safely past the fort. He told the Maracaibo citizens that they would not be sent ashore until the danger of the passage was removed. With this word he again set sail to attempt to pass the narrows. He found his ship still anchored near the wreck, but in more prosperous sort than he had left her. Her men had brought up 15,000 pieces of eight, with a lot of gold and silver plate, "as hilts of swords and other things," besides "great quantity of pieces of eight" which had "melted and run together" in the burning of the vessel.

Morgan now made a last appeal to the Spanish admiral, telling him that he would hang his prisoners if the fortress fired on him as he sailed past. The Spanish admiral sent an answer to the prisoners, who had begged him to relent, informing them that he would do his duty, as he wished they had done theirs. Morgan heard the[166] answer, and realised that he would have to use some stratagem to escape the threatened danger. He made a dividend of the plunder before he proceeded farther, for he feared that some of the fleet might never win to sea, and that the captains of those which escaped might be tempted to run away with their ships. The spoils amounted to 250,000 pieces of eight, as at Porto Bello, though in addition to this gold there were numbers of slaves and heaps of costly merchandise.

When the booty had been shared he put in use his stratagem. He embarked his men in the canoas, and bade them row towards the shore "as if they designed to land." When they reached the shore they hid under the overhanging boughs "till they had laid themselves down along in the boats." Then one or two men rowed the boats back to the ships, with the crews concealed under the thwarts. The Spaniards in the fortress watched the going and returning of the boats. They could not see the stratagem, for the boats were too far distant, but they judged that the pirates were landing for a night attack. The boats plied to and from the shore at intervals during the day. The anxious Spaniards resolved to prepare for the assault by placing their great guns on the landward side of the fortress. They cleared away the scrub on that side, in order to give their gunners a clear view of the attacking force when the sun set. They posted sentries, and stood to their arms, expecting to be attacked.

As soon as night had fallen the buccaneers weighed anchor. A bright moon was shining, and by the moonlight the ships steered seaward under bare poles. As they came abreast of the castle on the gentle current of the ebb, they loosed their sails to a fair wind blowing seaward. At the same moment, while the top-sails were[167] yet slatting, Captain Morgan fired seven great guns "with bullets" as a last defiance. The Spaniards dragged their cannon across the fortress, "and began to fire very furiously," without much success. The wind freshened, and as the ships drew clear of the narrows they felt its force, and began to slip through the water. One or two shots took effect upon them before they drew out of range, but "the Pirates lost not many of their men, nor received any considerable damage in their ships." They hove to at a distance of a mile from the fort in order to send a boat in with a number of the prisoners. They then squared their yards, and stood away towards Jamaica, where they arrived safely, after very heavy weather, a few days later. Here they went ashore in their stolen velvets and silks to spend their silver dollars in the Port Royal rum shops. Some mates of theirs were ashore at that time after an unlucky cruise. It was their pleasure "to mock and jeer" these unsuccessful pirates, "often telling them: Let us see what money you brought from Comana, and if it be as good silver as that which we bring from Maracaibo."

Note.—On his return from Maracaibo, Morgan gave out that he had met with further information of an intended Spanish attack on Jamaica. He may have made the claim to justify his actions on the Main, which were considerably in excess of the commission Modyford had given him. On the other hand, a Spanish attack may have been preparing, as he stated; but the preparations could not have gone far, for had the Spaniards been prepared for such an expedition Morgan's Panama raid could never have succeeded.

Authorities.—Exquemeling's "History of The Bucaniers of America"; Exquemeling's "History" (the Malthus edition), 1684. Cal. State Papers: West Indian and Colonial Series.

For my account of Porto Bello I am indebted to various brief accounts in Hakluyt, and to a book entitled "A Description of the Spanish Islands," by a "Gentleman long resident in those parts." I have also consulted the brief notices in Dampier's Voyages, Wafer's Voyages, various gazetteers, and some maps and pamphlets relating to Admiral Vernon's attack in 1739-40. There is a capital description of the place as it was in its decadence, circa 1820, in Michael Scott's "Tom Cringle's Log."