On the Spanish Main, by John Masefield

CHAPTER VIII

THE SPANISH RULE IN HISPANIOLA

Rise of the buccaneers—The hunters of the wild bulls—Tortuga—Buccaneer politics—Buccaneer customs

In 1492, when Columbus landed on Hayti, he found there about 1,000,000 Indians, of a gentle refinement of manners, living peaceably under their kings or caciques. They were "faint-hearted creatures," "a barbarous sort of people, totally given to sensuality and a brutish custom of life, hating all manner of labour, and only inclined to run from place to place." The Spaniards killed many thousands of them, hunted a number with their bloodhounds, sent a number to work the gold-mines, and caused about a third of the population to commit suicide or die of famine. They discouraged sensuality and a distaste for work so zealously that within twenty years they had reduced the population to less than a twentieth part of its original 1,000,000 of souls. They then called the island Hispaniola, and built a city, on the south coast, as the capital. This city they called Nueva Ysabel, in honour of the Queen of Spain, but the name was soon changed to that of St Domingo.[3]

Those Indians who were not enslaved, retired to the inmost parts of the island, to the shelter of the thickest woods, where they maintained themselves by hunting. The swine and cattle, which had belonged to their fellows in their prosperous days, ran wild, and swarmed all over the island in incredible numbers. The dogs of the[107] caciques also took to the woods, where they ranged in packs of two or three score, hunting the wild swine and the calves. The Spaniards seem to have left the interior of the island to the few survivors, as they had too few slaves to cultivate it. They settled themselves at St Domingo, and at various places upon the coast, such as Santiago and St John of Goave. They planted tobacco, sugar, chocolate, and ginger, and carried on a considerable trade with the cities on the Main and in the mother country.

Hayti, or Hispaniola, is in the fairway of ships coming from Europe towards the Main. It was at one time looked upon as the landfall to be made before proceeding west to Vera Cruz or south to Cartagena. The French, English, and Hollanders, who visited those seas "maugre the King of Spain's beard," discovered it at a very early date. They were not slow to recognise its many advantages. The Spanish, who fiercely resented the presence of any foreigners in a part of the world apportioned to Spain by the Pope, did all they could to destroy them whenever they had the opportunity. But the Spanish population in the Indies was small, and spread over a vast area, and restricted, by Government rules, to certain lines of action. They could not patrol the Indies with a number of guarda costas sufficient to exclude all foreign ships, nor could they set guards, in forts, at every estancia or anchorage in the vast coast-line of the islands. Nor could they enforce the Spanish law, which forbade the settlers to trade with the merchants of other countries. It often happened that a ship from France, Holland, or England arrived upon the coasts of Hispaniola, or some other Spanish colony, off some settlement without a garrison. The settlers in these out-of-the-way places were very glad to trade with such ships, for the freight they brought was cheaper and of better quality than that which paid duty to their King. The goods were landed,[108] and paid for. The ships sent their crews ashore to fill fresh water or to reprovision, and then sailed home for Europe, to return the next year with new goods. On the St Domingo or Hispaniola coasts there are countless creeks and inlets, making good harbours, where these smuggling ships might anchor or careen. The land was well watered and densely wooded, so that casks could be filled, and firewood obtained, without difficulty on any part of the coast. Moreover, the herds of wild cattle and droves of wild boars enabled the ships to reprovision without cost. Before the end of the sixteenth century, it had become the custom for privateers to recruit upon the coast of Hispaniola, much as Drake recruited at Port Plenty. The ships used to sail or warp into some snug cove, where they could be laid upon the careen to allow their barnacles to be burned away. The crews then landed, and pitched themselves tents of sails upon the beach, while some of their number took their muskets, and went to kill the cattle in the woods. In that climate, meat does not keep for more than a few hours, and it often happened that the mariners had little salt to spare for the salting of their kill. They, therefore, cured the meat in a manner they had learned from the Carib Indians. The process will be described later on.

The Spanish guarda costas, which were swift small vessels like the frigates Drake captured on the Main, did all they could to suppress the illegal trafficking. Their captains had orders to take no prisoners, and every "interloper" who fell into their hands was either hanged, like Oxenham, or shot, like Oxenham's mariners. The huntsmen in the woods were sometimes fired at by parties of Spaniards from the towns. There was continual war between the Spaniards, the surviving natives, and the interlopers. But when the Massacre of St Bartholomew drove many Huguenots across the water to follow the[109] fortunes of captains like Le Testu, and when the news of Drake's success at Nombre de Dios came to England, the interlopers began to swarm the seas in dangerous multitudes. Before 1580, the western coast of Hispaniola had become a sort of colony, to which the desperate and the adventurous came in companies. The ships used to lie at anchor in the creeks, while a number of the men from each ship went ashore to hunt cattle and wild boars. Many of the sailors found the life of the hunter passing pleasant. There were no watches to keep, no master to obey, no bad food to grumble at, and, better still, no work to do, save the pleasant work of shooting cattle for one's dinner. Many of them found the life so delightful that they did not care to leave it when the time came for their ships to sail for Europe. Men who had failed to win any booty on the "Terra Firma," and had no jolly drinking-bout to look for on the quays at home, were often glad to stay behind at the hunting till some more fortunate captain should put in in want of men. Shipwrecked men, men who were of little use at sea, men "who had disagreed with their commander," began to settle on the coast in little fellowships.[4] They set on foot a regular traffic with the ships which anchored there. They killed great quantities of meat, which they exchanged (to the ships' captains) for strong waters, muskets, powder and ball, woven stuffs, and iron-ware. After a time, they began to preserve the hides, "by pegging them out very tite on the Ground,"—a commodity of value, by which they made much money. The bones they did not seem to have utilised after they had split them for their marrow. The tallow and suet were sold to the ships—the one to grease the ships' bottoms when careened, the other as an article for export to the European countries. It was a wild life, full of merriment and danger. The Spaniards killed a[110] number of them, both French and English, but the casualties on the Spanish side were probably a good deal the heavier. The huntsmen became more numerous. For all that the Spaniards could do, their settlements and factories grew larger. The life attracted people, in spite of all its perils, just as tunny fishing attracted the young gallant in Cervantes. A day of hunting in the woods, a night of jollity, with songs, over a cup of drink, among adventurous companions—qué cosa tan bonita! We cannot wonder that it had a fascination. If a few poor fellows in their leather coats lay out on the savannahs with Spanish bullets in their skulls, the rum went none the less merrily about the camp fires of those who got away.

In 1586, on New Year's Day to be exact, Sir Francis Drake arrived off Hispaniola with his fleet. He had a Greek pilot with him, who helped him up the roads to within gunshot of St Domingo. The old Spanish city was not prepared for battle, and the Governor made of it "a New Year's gift" to the valorous raiders. The town was sacked, and the squadron sailed away to pillage Cartagena and St Augustine. Drake's raid was so successful that privateers came swarming in his steps to plunder the weakened Spanish towns. They settled on the west and north-west coasts of Hispaniola, compelling any Spanish settlers whom they found to retire to the east and south. The French and English had now a firm foothold in the Indies. Without assistance from their respective Governments they had won the right to live there, "maugre the King of Spain's beard." In a few years' time, they had become so prosperous that the Governments of France and England resolved to plant a colony in the Caribbee Islands, or Lesser Antilles. They thought that such a colony would be of benefit to the earlier adventurers by giving them official recognition and[111] protection. A royal colony of French and English was, therefore, established on the island of St Christopher, or St Kitts, one of the Caribbees, to the east of Hispaniola, in the year 1625. The island was divided between the two companies. They combined very amicably in a murderous attack upon the natives, and then fell to quarrelling about the possession of an island to the south.

As the Governments had foreseen, their action in establishing a colony upon St Kitts did much to stimulate the settlements in Hispaniola. The hunters went farther afield, for the cattle had gradually left the western coast for the interior. The anchorages by Cape Tiburon, or "Cape Shark," and Samana, were filled with ships, both privateers and traders, loading with hides and tallow or victualling for a raid upon the Main. The huntsmen and hidecurers, French and English, had grown wealthy. Many of them had slaves, in addition to other valuable property. Their growing wealth made them anxious to secure themselves from any sudden attack by land or sea.

At the north-west end of Hispaniola, separated from that island by a narrow strip of sea, there is a humpbacked little island, a few miles long, rather hilly in its centre, and very densely wooded. At a distance it resembles a swimming turtle, so that the adventurers on Hispaniola called it Tortuga, or Turtle Island. Later on, it was known as Petit Guaves. Between this Tortuga and the larger island there was an excellent anchorage for ships, which had been defended at one time by a Spanish garrison. The Spaniards had gone away, leaving the place unguarded. The wealthier settlers seized the island, built themselves factories and houses, and made it "their head-quarters, or place of general rendezvous." After they had settled there, they seem to have thought them[112]selves secure.[5] In 1638 the Spaniards attacked the place, at a time when nearly all the men were absent at the hunting. They killed all they found upon the island, and stayed there some little time, hanging those who surrendered to them after the first encounter. Having massacred some 200 or 300 settlers, and destroyed as many buildings as they could, the Spaniards sailed away, thinking it unnecessary to leave a garrison behind them. In this they acted foolishly, for their atrocities stirred the interlopers to revenge themselves. A band of them returned to Tortuga, to the ruins which the Spaniards had left standing. Here they formed themselves into a corporate body, with the intention to attack the Spanish at the first opportunity. Here, too, for the first time, they elected a commander. It was at this crisis in their history that they began to be known as buccaneers, or people who practise the boucan, the native way of curing meat. It is now time to explain the meaning of the word and to give some account of the modes of life of the folk who brought it to our language.

The Carib Indians, and the kindred tribes on the Brazilian coast, had a peculiar way of curing meat for preservation. They used to build a wooden grille or grating, raised upon poles some two or three feet high, above their camp fires. This grating was called by the Indians barbecue. The meat to be preserved, were it ox, fish, wild boar, or human being, was then laid upon the grille. The fire underneath the grille was kept low, and fed with green sticks, and with the offal, hide, and bones of the slaughtered animal. This process was called boucanning, from an Indian word "boucan," which seems to have signified "dried meat" and "camp-fire." Buccaneer, in its original sense, meant one who practised the boucan.[113]

Meat thus cured kept good for several months. It was of delicate flavour, "red as a rose," and of a tempting smell. It could be eaten without further cookery. Sometimes the meat was cut into pieces, and salted, before it was boucanned—a practice which made it keep a little longer than it would otherwise have done. Sometimes it was merely cut in strips, roughly rubbed with brine, and hung in the sun to dry into charqui, or jerked beef. The flesh of the wild hog made the most toothsome boucanned meat. It kept good a little longer than the beef, but it needed more careful treatment, as stowage in a damp lazaretto turned it bad at once. The hunters took especial care to kill none but the choicest wild boars for sea-store. Lean boars and sows were never killed. Many hunters, it seems, confined themselves to hunting boars, leaving the beeves as unworthy quarry.

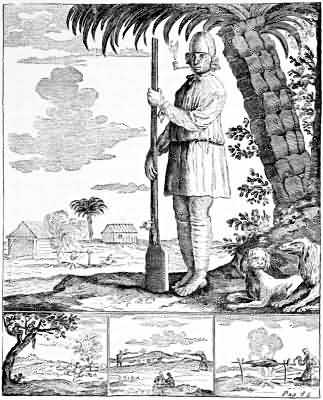

When hunting, the buccaneers went on foot, in small parties of four or five. The country in which they hunted was densely wooded, so that they could not ride. Each huntsman carried a gun of a peculiar make, with a barrel four and a half feet long and a spade-shaped stock. The long barrel made the gun carry very true. For ramrods they carried three or four straight sticks of lance wood—a wood almost as hard as iron, and much more easily replaced. The balls used, weighed from one to two ounces apiece. The powder was of the very best make known. It was exported specially from Normandy—a country which sent out many buccaneers, whose phrases still linger in the Norman patois. For powder flask they used a hollow gourd, which was first dried in the sun. When it had dried to a fitting hardness it was covered with cuir-bouilli, or boiled leather, which made it watertight. A pointed stopper secured the mouth, and made a sort of handle to the whole, by which it could be secured to the strap which the hunter slung across his shoulders. Each[114] hunter carried a light tent, made of linen or thin canvas. The tents rolled up into a narrow compass, like a bandolier, so that they could be carried without trouble. The woods were so thick that the leggings of the huntsmen had to be of special strength. They were made of bull or boar hide, the hair worn outwards.[6] Moccasins, or shoes for hunting, were made of dressed bull's hide. The clothes worn at sea or while out hunting were "uniformly slovenly." A big heavy hat, wide in the brim and running up into a peak, protected the wearer from sunstroke. A dirty linen shirt, which custom decreed should not be washed, was the usual wear. It tucked into a dirty pair of linen drawers or knickerbockers, which garments were always dyed a dull red in the blood of the beasts killed. A sailor's belt went round the waist, with a long machete or sheath-knife secured to it at the back. Such was the attire of a master hunter, buccaneer, or Brother of the Coast. Many of them had valets or servants sent out to them from France for a term of three years. These valets were treated with abominable cruelty, and put to all manner of bitter labour. A valet who had served his time was presented with a gun and powder, two shirts and a hat—an equipment which enabled him to enter business on his own account. Every hunting party was arranged on the system of share and share alike. The parties usually made their plans at the Tortuga taverns. They agreed with the sugar and tobacco planters to supply the plantations with meat in exchange for tobacco. They then loaded up their valets with hunters' necessaries, and sailed for Hispaniola. Often they remained in the woods for a year or two, sending their servants to the coast from time to time with loads of meat and hides. They hunted, as a rule, without dogs, though some sought out the whelps of the wild mastiffs and trained them to hunt the boars.[115] They stalked their quarry carefully, and shot it from behind a tree. In the evenings they boucanned their kill, pegged out the hides as tightly as they could, smoked a pipe or two about the fire, and prepared a glorious meal of marrow, "toute chaude"—their favourite dish. After supper they pitched their little linen tents, smeared their faces with grease to keep away the insects, put some wood upon the fire, and retired to sleep, with little thought of the beauty of the fireflies. They slept to leeward of the fires, and as near to them as possible, so that the smoke might blow over them, and keep off the mosquitoes. They used to place wet tobacco leaf and the leaves of certain plants among the embers in order that the smoke might be more pungent.

When the hunt was over, the parties would return to the coast to dispose of all they carried home, and to receive all they had earned during their absence. It was a lucrative business, and two years' hunting in the woods brought to each hunter a considerable sum of money. As soon as they touched their cash, they retired to Tortuga, where they bought new guns, powder, bullets, small shot, knives, and axes "against another going out or hunting." When the new munitions had been paid for, the buccaneers knew exactly how much money they could spend in self-indulgence. Those who have seen a cowboy on a holiday, or a sailor newly home from the seas, will understand the nature of the "great liberality" these hunters practised on such occasions. One who saw a good deal of their way of life[7] has written that their chief vice, or debauchery, was that of drunkenness, "which they exercise for the most part with brandy. This they drink as liberally as the Spaniards do clear fountain water. Sometimes they buy together a pipe of wine; this they stave at the one end, and never cease drinking till they have made an end[116] of it. Thus they celebrate the festivals of Bacchus so long as they have any money left." The island of Tortuga must have witnessed some strange scenes. We may picture a squalid little "cow town," with tropical vegetation growing up to the doors. A few rough bungalow houses, a few huts thatched with palm leaves, a few casks standing in the shade of pent roofs. To seaward a few ships of small tonnage lying at anchor. To landward hilly ground, broken into strips of tillage, where some wretches hoe tobacco under the lash. In the street, in the sunlight, lie a few savage dogs. At one of the houses, a buccaneer has just finished flogging his valet; he is now pouring lemon juice, mixed with salt and pepper, into the raw, red flesh. At another house, a gang of dirty men in dirty scarlet drawers are drinking turn about out of a pan of brandy. The reader may complete the sketch should he find it sufficiently attractive.

When the buccaneers elected their first captain, they had made but few determined forays against the Spaniards. The greater number of them were French cattle hunters dealing in boucanned meat, hides, and tallow. A few hunted wild boars; a few more planted tobacco of great excellence, with a little sugar, a little indigo, and a little manioc. Among the company were a number of wild Englishmen, of the stamp of Oxenham, who made Tortuga their base and pleasure-house, using it as a port from which to sally out to plunder Spanish ships. After a cruise, these pirates sometimes went ashore for a month or two of cattle hunting. Often enough, the French cattle hunters took their places on the ships. The sailors and huntsmen soon became amphibious, varying the life of the woods with that of a sailor, and sometimes relaxing after a cruise with a year's work in the tobacco fields. In 1638, when the Spanish made their raid, there were considerable numbers (certainly several hundreds) of men engaged in[117] these three occupations. After the raid they increased in number rapidly; for after the raid they began to revenge themselves by systematic raids upon the Spaniards—a business which attracted hundreds of young men from France and England. After the raid, too, the French and English Governments began to treat the planters of the St Kitts colony unjustly, so that many poor men were forced to leave their plots of ground there. These men left the colonies to join the buccaneers at Tortuga, who soon became so numerous that they might have made an independent state had they but agreed among themselves. This they could not do, for the French had designs upon Tortuga. A French garrison was landed on the island, seemingly to protect the French planters from the English, but in reality to seize the place for the French crown. Another garrison encamped upon the coast of the larger island. The English were now in a position like that of the spar in the tale.[8] They could no longer follow the business of cattle hunting; they could no longer find an anchorage and a ready market at Tortuga. They were forced, therefore, to find some other rendezvous, where they could refit after a cruise upon the Main. They withdrew themselves more and more from the French buccaneers, though the two parties frequently combined in enterprises of danger and importance. They seem to have relinquished Tortuga without fighting. They were less attached to the place than the French. Their holdings were fewer, and they had but a minor share in the cattle hunting. But for many years to come they regarded the French buccaneers with suspicion, as doubtful allies. When they sailed away from Tortuga they sought out other haunts on islands partly settled by the English.

In 1655, when an English fleet under Penn and Venables came to the Indies to attack the Spaniards, a body of[118] English buccaneers who had settled at Barbadoes came in their ships to join the colours. In all, 5000 of them mustered, but the service they performed was of poor quality. The combined force attacked St Domingo, and suffered a severe repulse. They then sailed for Jamaica, which they took without much difficulty. The buccaneers found Jamaica a place peculiarly suited to them: it swarmed with wild cattle; it had a good harbour; it lay conveniently for raids upon the Main. They began to settle there, at Port Royal, with the troops left there by Cromwell's orders. They planted tobacco and sugar, followed the boucan, and lived as they had lived in the past at Hispaniola. Whenever England was at war with Spain the Governor of the island gave them commissions to go privateering against the Spanish. A percentage of the spoil was always paid to the Governor, while the constant raiding on the Main prevented the Spaniards from attacking the new colony in force. The buccaneers were thus of great use to the Colonial Government. They brought in money to the Treasury and kept the Spanish troops engaged. The governors of the French islands acted in precisely the same way. They gave the French buccaneers every encouragement. When France was at peace with Spain they sent to Portugal ("which country was then at war with Spain") for Portuguese commissions, with which the buccaneer captains could go cruising. The English buccaneers often visited the French islands in order to obtain similar commissions. When England was at war with Spain the French came to Port Royal for commissions from the English Governor. It was not a very moral state of affairs; but the Colonial governors argued that the buccaneers were useful, that they brought in money, and that they could be disowned at any time should Spain make peace with all the interloping countries.

The buccaneers now began "to make themselves re[119]doubtable to the Spaniards, and to spread riches and abundance in our Colonies." They raided Nueva Segovia, took a number of Spanish ships, and sacked Maracaibo and western Gibraltar. Their captains on these raids were Frenchmen and Portuguese. The spoils they took were enormous, for they tortured every prisoner they captured until he revealed to them where he had hidden his gold. They treated the Spaniards with every conceivable barbarity, nor were the Spaniards more merciful when the chance offered.

The buccaneers, French and English, had a number of peculiar customs or laws by which their strange society was held together. They seem to have had some definite religious beliefs, for we read of a French captain who shot a buccaneer "in the church" for irreverence at Mass. No buccaneer was allowed to hunt or to cure meat upon a Sunday. No crew put to sea upon a cruise without first going to church to ask a blessing on their enterprise. No crew got drunk, on the return to port after a successful trip, until thanks had been declared for the dew of heaven they had gathered. After a cruise, the men were expected to fling all their loot into a pile, from which the chiefs made their selection and division. Each buccaneer was called upon to hold up his right hand, and to swear that he had not concealed any portion of the spoil. If, after making oath, a man were found to have secreted anything, he was bundled overboard, or marooned when the ship next made the land. Each buccaneer had a mate or comrade, with whom he shared all things, and to whom his property devolved in the event of death.[9] In many cases the partnership lasted during life. A love for his partner was usually the only tender sentiment a buccaneer allowed himself.

When a number of buccaneers grew tired of plucking[120] weeds[10] from the tobacco ground, and felt the allurement of the sea, and longed to go a-cruising, they used to send an Indian, or a negro slave, to their fellows up the coast, inviting them to come to drink a dram with them. A day was named for the rendezvous, and a store was cleared, or a tobacco drying-house prepared, or perhaps a tent of sails was pitched, for the place of meeting. Early on the morning fixed for the council, a barrel of brandy was rolled up for the refreshment of the guests, while the black slaves put some sweet potatoes in a net to boil for the gentlemen's breakfasts. Presently a canoa or periagua would come round the headland from the sea, under a single sail—the topgallant-sail of some sunk Spanish ship. In her would be some ten or a dozen men, of all countries, anxious for a cruise upon the Main. Some would be Englishmen from the tobacco fields on Sixteen-Mile Walk. One or two of them were broken Royalists, of gentle birth, with a memory in their hearts of English country houses. Others were Irishmen from Montserrat, the wretched Kernes deported after the storm of Tredah. Some were French hunters from the Hispaniola woods, with the tan upon their cheeks, and a habit of silence due to many lonely marches on the trail. The new-comers brought their arms with them: muskets with long single barrels, heavy pistols, machetes, or sword-like knives, and a cask or two of powder and ball. During the morning other parties drifted in. Hunters, and planters, and old, grizzled seamen came swaggering down the trackways to the place of meeting. Most of them were dressed in the dirty shirts and blood-stained drawers of the profession, but some there were who wore a scarlet cloak or a purple serape which had been stitched for a[121] Spaniard on the Main. Among the party were generally some Indians from Campeachy—tall fellows of a blackish copper colour, with javelins in their hands for the spearing of fish. All of this company would gather in the council chamber, where a rich planter sat at a table with some paper scrolls in front of him.

As soon as sufficient men had come to muster, the planter[11] would begin proceedings by offering a certain sum of money towards the equipment of a roving squadron. The assembled buccaneers then asked him to what port he purposed cruising. He would suggest one or two, giving his reasons, perhaps bringing in an Indian with news of a gold mine on the Main, or of a treasure-house that might be sacked, or of a plate ship about to sail eastward. Among these suggestions one at least was certain to be plausible. Another buccaneer would then offer to lend a good canoa, with, perhaps, a cask or two of meat as sea-provision. Others would offer powder and ball, money to purchase brandy for the voyage, or roll tobacco for the solace of the men. Those who could offer nothing, but were eager to contribute and to bear a hand, would pledge themselves to pay a share of the expenses out of the profits of the cruise. When the president had written down the list of contributions he called upon the company to elect a captain. This was seldom a difficult matter, for some experienced sailor—a good fellow, brave as a lion, and fortunate in love and war—was sure to be among them. Having chosen the captain, the company elected sailing masters, gunners, chirurgeons (if they had them), and the other officers necessary to the economy of ships of war. They then discussed the "lays" or shares to be allotted to each man out of the general booty.

Those who lent the ships and bore the cost of the pro[122]visioning, were generally allotted one-third of all the plunder taken. The captain received three shares, sometimes six or seven shares, according to his fortune. The minor officers received two shares apiece. The men or common adventurers received each one share. No plunder was allotted until an allowance had been made for those who were wounded on the cruise. Compensation varied from time to time, but the scale most generally used was as follows[12]:—"For the loss of a right arm six hundred pieces of eight, or six slaves; for the loss of a left arm five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for a right leg five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for a left leg four hundred pieces of eight, or four slaves; for an eye one hundred pieces of eight, or one slave; for a finger of the hand the same reward as for the eye."

In addition to this compensation, a wounded man received a crown a day (say three shillings) for two months after the division of the spoil. If the booty were too little to allow of the declaration of a dividend, the wounded were put ashore at the port of rendezvous, and the adventurers kept the seas until they had enough to bring them home.

In the years of buccaneer prosperity, when Port Royal was full of ruffians eager to go cruising, the proceedings may often have been less regular. A voyage was sometimes arranged in the taverns, where the gangs drank punch, or rumbo, a draught of rum and water (taken half-and-half, and sweetened with crude sugar) so long as their money lasted. If a gang had a ship, or the offer of a ship, and had but little silver left them from their last cruise, they would go aboard with their muskets, shot, and powder casks, trusting to fortune to obtain stores. Nearly every ship's company had a Mosquito Indian, or more than one, to act as guide ashore, in places where[123] a native's woodcraft was essential to a white man's safety. At sea these Indians supplied the mariners with fish, for they were singularly skilful with the fish spear. When a gang of buccaneers put to sea without provisions, they generally steered to the feeding grounds of the sea-turtles, or to some place where the sea-cows, or manatees, were found.[13] Here the Indians were sent out in small canoas, with their spears and tortoise irons. The spears were not unlike our modern harpoons. The tortoise irons were short, heavy arrow heads, which penetrated the turtle's shell when rightly thrown. The heads were attached to a stick, and to a cord which they made of a fibrous bark. When the blow had gone home, the stick came adrift, leaving the iron in the wound, with the cord still fast to it. When the turtles had been hauled aboard, their flesh was salted with the brine taken from the natural salt-pans to be found among the islands. When a manatee was killed, the hide was stripped away, and hung to dry. It was then cut into thongs, and put to various uses. The buccaneers made grummets, or rings, of it, for use in their row boats instead of tholes or rowlocks. The meat of manatee, though extremely delicate, did not take salt so readily as that of turtles. Turtle was the stand-by of the hungry buccaneer when far from the Main or the Jamaican barbecues. In addition to the turtle they had a dish of fish whenever the Indians were so fortunate as to find a shoal, or when the private fishing lines, of which each sailor carried several, were successful. Two Mosquito Indians, it was said, could keep 100 men in fish with no other weapons than their spears and irons. In coasting along the Main, a buccaneer captain could always obtain sufficient food for his immediate need, for hardly any part of the coast was destitute of land-crabs, oysters, fruit, deer, peccary, or warree. But for[124] a continued cruise with a large crew this hand-to-mouth supply was insufficient.

The buccaneers sometimes began a cruise by sailing to an estancia in Hispaniola, or on the Main, where they might supply their harness casks with flesh. They used to attack these estancias, or "hog-yards," at night. They began by capturing the swine or cattle-herds, and threatening them with death should they refuse to give them the meat they needed. Having chosen as many beeves or swine as seemed sufficient for their purpose, they kicked the herds for their pains, and put the meat in pickle.[14] They then visited some other Spanish house for a supply of rum or brandy, or a few hat-loads of sugar in the crude. Tobacco they stole from the drying-rooms of planters they disliked. Lemons, limes, and other anti-scorbutics they plucked from the trees, when fortune sent them to the coast. Flour they generally captured from the Spanish. They seldom were without a supply, for it is often mentioned as a marching ration—"a doughboy, or dumpling," boiled with fat, in a sort of heavy cake, a very portable and filling kind of victual. At sea their staple food was flesh—either boucanned meat or salted turtle. Their allowance, "twice a day to every one," was "as much as he can eat, without either weight or measure." Water and strong liquors were allowed (while they lasted) in the same liberal spirit. This reckless generosity was recklessly abused. Meat and drink, so easily provided, were always improvidently spent. Probably few buccaneer ships returned from a cruise with the hands on full allowance. The rule was "drunk and full, or dry and empty, to hell with bloody misers"—the proverb of the American merchant sailor of to-day. They knew no mean in anything. That which came easily might go lightly: there was more where that came from.

When the ship had been thus victualled the gang went aboard her to discuss where they should go "to seek their desperate fortunes." The preliminary agreement was put in writing, much as in the former case, allotting each man his due share of the expected spoil. We read that the carpenter who "careened, mended, and rigged the vessel" was generally allotted a fee of from twenty-five to forty pounds for his pains—a sum drawn from the common stock or "purchase" subsequently taken by the adventurers. For the surgeon "and his chest of medicaments" they provided a "competent salary" of from fifty to sixty pounds. Boys received half-a-share, "by reason that, when they take a better vessel than their own, it is the duty of the boys to set fire to the ship or boat wherein they are, and then retire to the prize which they have taken." All shares were allotted on the good old rule: "No prey, No pay," so that all had a keen incentive to bestir themselves. They were also "very civil and charitable to each other," observing "among themselves, very good orders." They sailed together like a company of brothers, or rather, since that were an imperfect simile, like a company of jolly comrades. Locks and keys were forbidden among them, as they are forbidden in ship's fo'c's'les to this day; for every man was expected to show that he put trust in his mates. A man caught thieving from his fellow was whipped about the ship by all hands with little whips of ropeyarn or of fibrous maho bark. His back was then pickled with some salt, after which he was discharged the company. If a man were in want of clothes, he had but to ask a shipmate to obtain all he required. They were not very curious in the rigging or cleansing of their ships; nor did they keep watch with any regularity. They set their Mosquito Indians in the tops to keep a good lookout; for the Indians were long-sighted folk, who could descry[126] a ship at sea at a greater distance than a white man. They slept, as a rule, on "mats" upon the deck, in the open air. Few of them used hammocks, nor did they greatly care if the rain drenched them as they lay asleep.

After the raids of Morgan, the buccaneers seem to have been more humane to the Spaniards whom they captured. They treated them as Drake treated them, with all courtesy. They discovered that the cutting out of prisoners' hearts, and eating of them raw without salt, as had been the custom of one of the most famous buccaneers, was far less profitable than the priming of a prisoner with his own aqua-vitæ. The later buccaneers, such as Dampier, were singularly zealous in the collection of information of "the Towns within 20 leagues of the sea, on all the coast from Trinidado down to La Vera Cruz; and are able to give a near guess of the strength and riches of them." For, as Dampier says, "they make it their business to examine all Prisoners that fall into their hands, concerning the Country, Town, or City that they belong to; whether born there, or how long they have known it? how many families? whether most Spaniards? or whether the major part are not Copper-colour'd, as Mulattoes [people half white, half black], Mustesoes [mestizos, or people half white, half Indian. These are not the same as mustees, or octoroons], or Indians? whether rich, and what their riches do consist in? and what their chiefest manufactures? If fortified, how many Great Guns, and what number of small Arms? whether it is possible to come undescried on them? How many Look-outs or Centinels? for such the Spaniards always keep; and how the Look-outs are placed? Whether possible to avoid the Look-outs or take them? If any River or Creek comes near it, or where the best Landing? or numerous other such questions, which their curiosities[127] lead them to demand. And if they have had any former discourse of such places from other Prisoners, they compare one with the other; then examine again, and enquire if he or any of them, are capable to be guides to conduct a party of men thither: if not, where and how any Prisoner may be taken that may do it, and from thence they afterwards lay their Schemes to prosecute whatever design they take in hand."

If, after such a careful questioning as that just mentioned, the rovers decided to attack a city on the Main at some little distance from the sea, they would debate among themselves the possibility of reaching the place by river. Nearly all the wealthy Spanish towns were on a river, if not on the sea; and though the rivers were unwholesome, and often rapid, it was easier to ascend them in boats than to march upon their banks through jungle. If on inquiry it were found that the suggested town stood on a navigable river, the privateers would proceed to some island, such as St Andreas, where they could cut down cedar-trees to make them boats. St Andreas, like many West Indian islands, was of a stony, sandy soil, very favourable to the growth of cedar-trees. Having arrived at such an island, the men went ashore to cut timber. They were generally good lumbermen, for many buccaneers would go to cut logwood in Campeachy when trade was slack. As soon as a cedar had been felled, the limbs were lopped away, and the outside rudely fashioned to the likeness of a boat. If they were making a periagua, they left the stern "flat"—that is, cut off sharply without modelling; if they were making a canoa, they pointed both ends, as a Red Indian points his birch-bark. The bottom of the boat in either case was made flat, for convenience in hauling over shoals or up rapids. The inside of the boat was hollowed out by fire, with the help of the Indians, who were very expert at the management[128] of the flame. For oars they had paddles made of ash or cedar plank, spliced to the tough and straight-growing lance wood, or to the less tough, but equally straight, white mangrove. Thwarts they made of cedar plank. Tholes or grummets for the oars they twisted out of manatee hide. Having equipped their canoas or periaguas they secured them to the stern of their ship, and set sail towards their quarry.

Authorities.—Captain James Burney: "Voyages and Discoveries in the South Sea"; "History of the Buccaneers." Père Charlevoix: "Histoire de l'Isle Espagnole"; "Histoire et description de la N. France." B. Edwards: "Historical Survey of the Island of San Domingo." Gage: "Histoire de l'Empire Mexicain"; "The English American." S. Hazard: "Santo Domingo, Past and Present." Justin: "Histoire Politique de l'Isle de Haïti." Cal. State Papers: "America and West Indies." Abbé Raynal: "History of the Settlements and Trades of the Europeans in the East and West Indies." A. O. Exquemeling: "History of the Buccaneers." A. de Herrera: "Description des Indes Occidentales (d'Espagnol)." J. de Acosta: "History of the Indies." Cieça de Leon: "Travels."

[3] See particularly Burney, Exquemeling, Edwards, and Hazard.

[4] See Exquemeling, Burney, and the Abbé Raynal.

[5] Burney.

[6] See Burney, and Exquemeling.

[7] Exquemeling.

[8] Precarious, and not at all permanent.

[9] Similar pacts of comradeship are made among merchant sailors to this day.

[10] Exquemeling gives many curious details of the life of these strange people. See the French edition of "Histoire des Avanturiers."

[11] Exquemeling gives these details.

[12] Exquemeling.

[13] Dampier.

[14] Exquemeling.