Chapter XL: The Death Of Baldur - The Elves - Runic Letters - Skalds - Iceland

THE DEATH OF BALDUR.

Baldur. p. 427 1908 Edition

BALDUR the Good, having been tormented with terrible dreams indicating that his life was in peril, told them to the assembled gods, who resolved to conjure all things to avert from him the threatened danger.

Then Frigga, the wife of Odin, exacted an oath from fire and water, from iron and all other metals, from stones, trees, diseases, beasts, birds, poisons, and creeping things, that none of them would do any harm to Baldur. Odin, not satisfied with all this, and feeling alarmed for the fate of his son, determined to consult the prophetess Angerbode, a giantess, mother of Fenris, Hela, and the Midgard serpent. She was dead, and Odin was forced to seek her in Hela’s dominions. This Descent of Odin forms the subject of Gray’s fine ode beginning:

“Uprose the king of men with speed

And saddled straight his coal-black steed.”

[ See: The Descent of Odin ]

[ See: The Children of Odin by Padraic Colum ]

[ See: Dictionary Of Norse Gods And Goddesses by Viktor Rydberg ]

[ See: The Death Of Baldur in The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson ]

But the other gods, feeling that what Frigga had done was quite sufficient, amused themselves with using Baldur as a mark, some hurling darts at him, some stones, while others hewed at him with their swords and battle–axes; for do what they would, none of them could harm him.

And this became a favourite pastime with them and was regarded as an honour shown to Baldur. But when Loki beheld the scene he was sorely vexed that Baldur was not hurt. Assuming, therefore, the shape of a woman, he went to Fensalir, the mansion of Frigga. That goddess, when she saw the pretended woman, inquired of her if she knew what the gods were doing at their meetings. She replied that they were throwing darts and stones at Baldur, without being able to hurt him.

“Ay,” said Frigga, “neither stones, nor sticks, nor anything else can hurt Baldur, for I have exacted an oath from all of them.”

“What,” exclaimed the woman, “have all things sworn to spare Baldur?”

“All things,” replied Frigga, “except one little shrub that grows on the eastern side of Valhalla, and is called Mistletoe, and which I thought too young and feeble to crave an oath from.”

As soon as Loki heard this he went away, and resuming his natural shape, cut off the mistletoe, and repaired to the place where the gods were assembled. There he found Hodur standing apart, without partaking of the sports, on account of his blindness, and going up to him, said,

“Why dost thou not also throw something at Baldur?”

“Because I am blind,” answered Hodur, “and see not where Baldur is, and have, moreover, nothing to throw.”

“Come, then,” said Loki, “do like the rest, and show honour to Baldur by throwing this twig at him, and I will direct thy arm towards the place where he stands.”

Hodur then took the mistletoe, and under the guidance of Loki, darted it at Baldur, who, pierced through and through, fell down lifeless. Surely never was there witnessed, either among gods or men, a more atrocious deed than this.

When Baldur fell, the gods were struck speechless with horror, and then they looked at each other and all were of one mind to lay hands on him who had done the deed, but they were obliged to delay their vengeance out of respect for the sacred place where they were assembled. They gave vent to their grief by loud lamentations.

When the gods came to themselves, Frigga asked who among them wished to gain all her love and good will.

“For this,” said she, “shall he have who will ride to Hel and offer Hela a ransom if she will let Baldur return to Asgard.”

The Ardre image stone is thought to show Odin entering Valhalla riding on Sleipnir

In Norse mythology, Sleipnir is Odin's magical eight-legged steed, and the greatest of all horses. His name means smooth or gliding, and is related to the English word, "slippery".

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaWhereupon Hermod, surnamed the Nimble, the son of Odin, offered to undertake the journey. Odin’s horse, Sleipnir, which has eight legs and can outrun the wind, was then led forth, on which Hermod mounted and galloped away on his mission. For the space of nine days and as many nights he rode through deep glens so dark that he could not discern anything, until he arrived at the river Gyoll, which he passed over on a bridge covered with glittering gold. The maiden who kept the bridge asked him his name and lineage, telling him that the day before five bands of dead persons had ridden over the bridge, and did not shake it as much as he alone.

“But,” she added, “thou hast not death’s hue on thee; why then ridest thou here on the way to Hel?”

“I ride to Hel,” answered Hermod, “to seek Baldur. Hast thou perchance seen him pass this way?”

She replied,

“Baldur hath ridden over Gyoll’s bridge, and yonder lieth the way he took to the abodes of death.”

Hermod pursued his journey until he came to the barred gates of Hel. Here he alighted, girthed his saddle tighter, and remounting clapped both spurs to his horse, who cleared the gate by a tremendous leap without touching it. Hermod then rode on to the palace, where he found his brother Baldur occupying the most distinguished seat in the hall, and passed the night in his company. The next morning he besought Hela to let Baldur ride home with him, assuring her that nothing but lamentations were to be heard among the gods. Hela answered that it should now be tried whether Baldur was so beloved as he was said to be. “If, therefore,” she added, “all things in the world, both living and lifeless, weep for him, then shall he return to life; but if any one thing speak against him or refuse to weep, he shall be kept in Hel.”

Hermod then rode back to Asgard and gave an account of all he had heard and witnessed.

[ See: Asgard and the Gods ]

The gods upon this despatched messengers throughout the world to beg everything to weep in order that Baldur might be delivered from Hel. All things very willingly complied with this request, both men and every other living being, as well as earths, and stones, and trees, and metals, just as we have all seen these things weep when they are brought from a cold place into a hot one. As the messengers were returning, they found an old hag named Thaukt sitting in a cavern, and begged her to weep Baldur out of Hel. But she answered:

“Thaukt will wail

With dry tears

Baldur’s bale-fire.

Let Hela keep her own.”

It was strongly suspected that this hag was no other than Loki himself, who never ceased to work evil among gods and men. So Baldur was prevented from coming back to Asgard.

In Longfellow’s Poems will be found a poem entitled “Tegner’s Drapa,” upon the subject of Baldur’s death.

[ See: The Saga of King Olaf by Longfellow ]

[ See: The Influence of Old Norse Literature on English Literature ]

[ See: Gods and Goddesses of the Northland ]

THE FUNERAL OF BALDUR.

The gods took up the dead body and bore it to the seashore where stood Baldur’s ship “Hringham,” which passed for the largest in the world. Baldur’s dead body was put on the funeral pile, on board the ship, and his wife Nanna was so struck with grief at the sight that she broke her heart, and her body was burned on the same pile with her husband’s.

There was a vast concourse of various kinds of people at Baldur’s obsequies. First came Odin accompanied by Frigga, the Valkyrior, and his ravens; then Frey in his car drawn by Gullinbursti, the boar; Heimdall rode his horse Gulltopp, and Freya drove in her chariot drawn by cats. There were also a great many Frost giants and giants of the mountain present. Baldur’s horse was led to the pile fully caparisoned and consumed in the same flames with his master.

But Loki did not escape his deserved punishment. When he saw how angry the gods were, he fled to the mountain, and there built himself a hut with four doors, so that he could see every approaching danger. He invented a net to catch the fishes, such as fishermen have used since his time. But Odin found out his hiding–place and the gods assembled to take him.

He, seeing this, changed himself into a salmon, and lay hid among the stones of the brook. But the gods took his net and dragged the brook, and Loki, finding he must be caught, tried to leap over the net; but Thor caught him by the tail and compressed it, so that salmons ever since have had that part remarkably fine and thin. They bound him with chains and suspended a serpent over his head, whose venom falls upon his face drop by drop. His wife Siguna sits by his side and catches the drops as they fall, in a cup; but when she carries it away to empty it, the venom falls upon Loki, which makes him howl with horror, and twist his body about so violently that the whole earth shakes, and this produces what men call earthquakes.

[ See: Edda Volume I ] [ Edda Volume II ] [ The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson ]

[ Myths Of Scandinavia ] [ Thor's Adventure among the Jotuns ] [ The Apples Of Idun ]

[ The Gifts of the Dwarfs ] [ The Punishment of Loki ] [ Origin Of Jack The Giant Killer ]

THE ELVES.

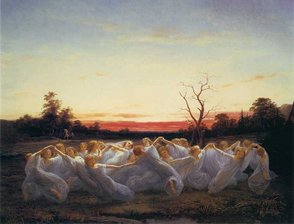

Ängsälvor, "meadow elves", (1850), painting by Nils

Blommér.The elves could be seen dancing over meadows,

particularly at night and on misty mornings. They left a kind of

circle were they had danced, which were called älvdanser

(elf dances) or älvringar (elf circles), and to urinate in

one was thought to cause venereal diseases.

Typically, it consisted of a ring of small mushrooms, but there

was also another kind of elf circle.

The Edda mentions another class of beings, inferior to the gods, but still possessed of great power; these were called Elves. The white spirits, or Elves of Light, were exceedingly fair, more brilliant than the sun, and clad in garments of a delicate and transparent texture. They loved the light, were kindly disposed to mankind, and generally appeared as fair and lovely children. Their country was called Alfheim, and was the domain of Freyr, the god of the sun, in whose light they were always sporting.

The black or Night Elves were a different kind of creatures. Ugly, long–nosed dwarfs, of a dirty brown colour, they appeared only at night, for they avoided the sun as their most deadly enemy, because whenever his beams fell upon any of them they changed them immediately into stones. Their language was the echo of solitudes, and their dwelling–places subterranean caves and clefts.

They were supposed to have come into existence as maggots produced by the decaying flesh of Ymir’s body, and were afterwards endowed by the gods with a human form and great understanding.

They were particularly distinguished for a knowledge of the mysterious powers of nature, and for the runes which they carved and explained. They were the most skilful artificers of all created beings, and worked in metals and in wood. Among their most noted works were Thor’s hammer, and the ship “Skidbladnir,” which they gave to Freyr, and which was so large that it could contain all the deities with their war and household implements, but so skilfully was it wrought that when folded together it could be put into a side pocket.

[ See:Elves ]

[ See: Elves And Heroes ]

RAGNAROK, THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS.

Tenth century CE stone cross at Gosfird, UK, showing details of the battle of the Norse gods

It was a firm belief of the northern nations that a time would come when all the visible creation, the gods of Valhalla and Niffleheim, the inhabitants of Jotunheim, Alfheim, and Midgard, together with their habitations, would be destroyed.

The fearful day of destruction will not, however, be without its forerunners. First will come a triple winter, during which snow will fall from the four corners of the heavens, the frost be very severe, the wind piercing, the weather tempestuous, and the sun impart no gladness. Three such winters will pass away without being tempered by a single summer.

Three other similar winters will then follow, during which war and discord will spread over the universe. The earth itself will be frightened and begin to tremble, the sea leave its basin, the heavens tear asunder, and men perish in great numbers, and the eagles of the air feast upon their still quivering bodies.

The wolf Fenris will now break his bands, the Midgard serpent rise out of her bed in the sea, and Loki, released from his bonds, will join the enemies of the gods. Amidst the general devastation the sons of Muspelheim will rush forth under their leader Surtur, before and behind whom are flames and burning fire. Onward they ride over Bifrost, the rainbow bridge, which breaks under the horses’ hoofs. But they, disregarding its fall, direct their course to the battlefield called Vigrid. Thither also repair the wolf Fenris, the Midgard serpent, Loki with all the followers of Hela, and the Frost giants.

Heimdall now stands up and sounds the Giallar horn to assemble the gods and heroes for the contest. The gods advance, led on by Odin, who engages the wolf Fenris, but falls a victim to the monster, who is, however, slain by Vidar, Odin’s son.

Thor gains great renown by killing the Midgard serpent, but recoils and falls dead, suffocated with the venom which the dying monster vomits over him. Loki and Heimdall meet and fight till they are both slain. The gods and their enemies having fallen in battle, Surtur, who has killed Freyr, darts fire and flames over the world, and the whole universe is burned up. The sun becomes dim, the earth sinks into the ocean, the stars fall from heaven, and time is no more.

After this Alfadur (the Almighty) will cause a new heaven and a new earth to arise out of the sea. The new earth filled with abundant supplies will spontaneously produce its fruits without labour or care. Wickedness and misery will no more be known, but the gods and men will live happily together.

[ See: Ragnarok: The Age Of Fire And Gravel ]

[ See: Ragnarok. The Fate of the Gods ]

RUNIC LETTERS.

Younger Futhark inscription on the Vaksala Runestone

One cannot travel far in Denmark, Norway, or Sweden without meeting with great stones of different forms, engraven with characters called Runic, which appear at first sight very different from all we know. The letters consist almost invariably of straight lines, in the shape of little sticks either singly or put together. Such sticks were in early times used by the northern nations for the purpose of ascertaining future events. The sticks were shaken up, and from the figures that they formed a kind of divination was derived.

The Runic characters were of various kinds. They were chiefly used for magical purposes. The noxious, or, as they called them, the bitter runes, were employed to bring various evils on their enemies; the favourable averted misfortune. Some were medicinal, others employed to win love, etc. In later times they were frequently used for inscriptions, of which more than a thousand have been found. The language is a dialect of the Gothic, called Norse, still in use in Iceland. The inscriptions may therefore be read with certainty, but hitherto very few have been found which throw the least light on history. They are mostly epitaphs on tombstones.

See: An Exposition on Runic Practises ]

[ See: Runes And Runic Practices ]

Gray’s ode on the “Descent of Odin” contains an allusion to the use of Runic letters for incantation:

“Facing to the northern clime,

Thrice he traced the Runic rhyme;

Thrice pronounced, in accents dread

The thrilling verse that wakes the dead,

Till from out the hollow ground

Slowly breathed a sullen sound.”

THE SKALDS.

The Skalds were the bards and poets of the nation, a very important class of men in all communities in an early stage of civilization. They are the depositaries of whatever historic lore there is, and it is their office to mingle something of intellectual gratification with the rude feasts of the warriors, by rehearsing, with such accomplishments of poetry and music as their skill can afford, the exploits of their heroes, living or dead. The compositions of the Skalds were called Sagas, many of which have come down to us, and contain valuable materials of history, and a faithful picture of the state of society at the time to which they relate.

[ See: The Life and Death of Cormac the Skald ]

ICELAND.

The Eddas and Sagas have come to us from Iceland. The following extract from Carlyle’s lectures on “Heroes and Hero Worship” (Lecture 1) gives an animated account of the region where the strange stories we have been reading had their origin. Let the reader contrast it for a moment with Greece, the parent of classical mythology:

“In that strange island, Iceland,– burst up, the geologists say, by fire from the bottom of the sea, a wild land of barrenness and lava, swallowed many months of every year in black tempests, yet with a wild, gleaming beauty in summer time, towering up there stern and grim in the North Ocean, with its snow yokuls [mountains], roaring geysers [boiling springs], sulphur pools, and horrid volcanic chasms, like the waste, chaotic battlefield of Frost and Fire,– where, of all places, we least looked for literature or written memorials,– the record of these things was written down. On the seaboard of this wild land is a rim of grassy country, where cattle can subsist, and men by means of them and of what the sea yields; and it seems they were poetic men these, men who had deep thoughts in them and uttered musically their thoughts. Much would be lost had Iceland not been burst up from the sea, not been discovered by the Northmen!”

[ See: On Heroes and Hero Worship And The Heroic In History ]

[ See: Olaf the Glorious A Story of the Viking Age ]