Asgard and the Gods

The Tales and Traditions of Our Northern Ancestors

INTRODUCTION

Just as in the olden time, Odin, the thoughtful god, gave his eye in pledge to the wise giant, Mimir, at Mimir's Well, for a draught of primeval wisdom, so men, longing for knowledge and loving the history of old Germany, sought for the great goddess Saga with untiring diligence, until at length they found her. She dwelt in a house of crystal beneath the cool flowing river. The eager enquirers went to her, and asked her to tell them about the olden times, and about the vanished races which had once ruled, suffered, fought and conquered, in the north of Europe. They found the goddess sunk in dreamy thought, while Odin's ravens fluttered around her, and whispered to her of the past and of the future. She rose from her throne, startled by the numerous questions addressed to her. She pointed to the scrolls which were lying scattered around her, as she said: "Are ye come at last to seek intelligence of the wisdom and deeds of your ancestors? I have written on these scrolls all that the people of that distant land thought and believed, and that which they held to be eternal truth. I went with these mighty races to their new homes, and have faithfully chronicled their struggles and attainments, their deeds, sufferings and victories, their gods and their heroes. No one has inquired for these documents in the long years that are past; so the storms of time and the glowing flames of Surtur have caused the loss and destruction of many of them. Seek out and gather together such as remain. Ye will find much wisdom hidden therein, when ye can read the writing and understand the meaning of the pictures."

The men sought out and collected as many of the scrolls as they were able. They arranged them in order, but found, as Saga had told them, that very many were lost, and others only existed as fragments. In addition to that, the runic writing on the documents was hard to read, and the true meaning of the faded pictures uncertain. Nevertheless, they allowed no difficulties to terrify them, but courageously pursued their work of investigation. Soon they discovered other records, or fragments of records, which they had supposed to have been lost. What the storms of time had scattered in different directions, what ignorance had cast aside as worthless, they brought to the light of day, often from hidden dusty corners and from the cottages of the poor. They arranged their discoveries in proper order, learnt to read the mystic signs on the documents, and the veil fell away before their increased knowledge. The old Germanic world, with its secrets and wonders, and the views of its ancient people regarding their gods and heroes, which were formerly lost in the darkness of the past, were now visible in the light of the present. We intend to give, in the following pages, the treasures that were thus rescued from oblivion, and to interweave with them many scraps of information which are rapidly dying out and being forgotten. We have endeavoured to make the book as interesting as possible, to induce both the young and the old to examine of what Teutonic genius was capable in the early dawn of its history, a history which in modern times has shown its descendants crowned with immortal laurels on many a blood-red field of battle. The religious conceptions of the most famous nations of antiquity are connected with the beginnings of civilization amongst the Germanic races. If we unflinchingly follow out the traces of a common origin, in spite of the difficulties in our way, we shall often find that the gods of the heathen Asgard, and the tales about them, though apparently dissimilar, really have their basis in the customs and opinions held in the country in which they all had their birth, and that in their early stages they were more or less connected. Although in Central Asia, on the banks of the Indus, in the Land of the Pyramids, in the Greek and Italian peninsulas, and even in the North, whither Kelts, Teutons and Slavs wandered, the religious conceptions of the people have taken different forms, yet their common origin is still perceptible. We point out this connection between the stories of the gods, and the deep thought contained in them, and their importance, in order that the reader may see that it is not a magic world of erratic fancy which is opened out before him, but that, according to Germanic intuition, Life and Nature formed the basis of the existence and action of these divinities. Before we proceed to study each individual deity in his fulness and imposing grandeur, let us, for the better understanding of the subject, rapidly pass their distinguishing characteristics in review.

The Myths and Stories of the Gods of Norse antiquity come first in order. We shall see, as our work goes on, that their origin is to be found in the early home of the Aryan races in the far East, when the spirit of man in the childhood of the world bowed down before those phenomena of surrounding nature which exercised a decisive influence on the struggles and life of humanity. Our ancestors, like all other primitive folk, believed firmly in the personality of these phenomena. All occurrences in the external world, the causes of which were unknown, and all facts of mental perception gradually assumed a human form in the mind of the people. During their wanderings these were as yet vague; but after their settlement in their new home they got further developed by wise seers and bards into typical forms; and then, as time went on, increased in number, until at length they faded away as the old faith died out, or was thrust aside by a new religion. Besides this, we find that many mythical figures arose from the Teutons being brought in contact with other nations; others again, and these the greater number, were due to the idiosyncrasies and characteristics of the Germanic race, and to the climate and mode of life pursued in their new home. Next come the myths about the creation of the world, the gods and their deeds.

The Gods, their Worlds and Deeds

In the abyss of immeasurable space the ice streams, Eliwagar, roll their blocks of ice; the heat from the South creates life in the frozen waters, and the giant Ymir, the blustering, boisterous, erratic, untamed power of Nature, comes into being. At the same time as the clay-giant, arises the cow, Audumla. She licks the salt-rock, and then the divine Buri is born. His grandsons, Odin, Wili, and We, conquer and kill the raging Ymir, and create the world out of his body. The giant's children are all drowned in his blood, except Bergelmir, who saves himself in a boat, and becomes the father of the giants. The flood is here described, and the giants are to the northern mind what Ahriman, the Principle of Evil, was to the Iranian. The gods point out to the sun and moon, day and night, the courses they must follow in chariots drawn by swift horses, after having completed which they are allowed to sink into the sea to rest. The deities created the first men out of trees - Ask (the ash), and Embla (the alder). Odin gave them life and soul, Hönir endowed them with intellect, and Lodur with blood and color.

In the dark caverns of the earth the Black-Dwarfs, or Elves of Darkness, creep about and make artistic utensils for the divine Æsir, the Ases, by whom they were created. The Elves of Light on the contrary, have their dwelling-place in the heavenly realms. The latter are pure and good, while the former are often wily and treacherous, but still are not bad enough to be the companions of the wicked giants (known as the Jotuns), who continually fight against both gods and man. As we learn from the myths which follow, two horrible monsters are allied with these giants, and they are to help to decide the Last Battle. They are the Fenris-Wolf and the Midgard-Snake, which latter, lying at the bottom of the sea, encircles the earth (the dwelling-place of the living); and they are abetted by direful Hel, the goddess-queen of the country of the dead.

Hidden or chained in the depths out of sight, these monsters await their time. In like manner dark Surtur, with his flaming sword, and the fiery sons of Muspel, lie in ambush in the hot south country. They are preparing themselves for the decisive battle, when heaven and earth, gods and man, are all to pass away.

Odin, Wodan, Wuotan

The scene changes; the separate figures of the gods stand out in their characteristic forms as northern imagination and Germanic poets have created them in the likeness of their heroes. First of these is Wodan, the Odin of Southern Germany, the god of battles, armed with his war-spear Gungnir, the death-giving lightning-flash, and followed by the Walkyries, the choosers of the dead, who consecrate the fallen heroes with a kiss, and bear them away to the halls of the gods, where they enjoy the feasts of the blessed. In the very earliest times all Germanic races prayed to Wodan for victory, as we shall see further on. He it is who rushes through the air in the midst of the howling storm, with his tumultuous host, the Wild Hunt, following after him. In the arms of Gunlöd he quaffs Odrörir, the draught of inspiration, and shares it with the seers and bards, and with those warriors who, for the sake of freedom and fatherland, have thrown themselves into the fiery death of battle. Trusting in his wisdom, he goes to Wafthrudnir, to take part in that contest in which the fighting consists of the clash of intellect against intellect in enigmatical speech, and he is victorious in this dangerous combat.

Later, he invents the Runes, through which he gains the power of understanding, penetrating and ruling all things. Thus he becomes the Spirit of Nature, - he becomes Allfather.

Frigga, or Freya, and her Handmaids

Next to Odin appears Frigga, the mother of the gods, seated on her throne Hlidskialf. Amongst the Germans she was looked upon as the same as Frea, the northern Freya, and was worshipped as the all-nourishing mother Earth. Three divine maidens form the household of the goddess; her favourite attendant Fulla or Plenty, helps her to dress, and carries her jewel-case after her; the undaunted horsewoman Gna, bears her orders to all parts of the nine worlds; and the faithful Hlyn protects her votaries. Frigga holds council with her husband regarding the fate of the world, or sits in her hall Fensal, with her handmaids, and spins golden thread with which to reward the diligence of men. In later traditions she is sometimes represented as a cunning housewife gaining all her ends by craft; but in the old legends she is uniformly represented under the names of Holda and Berchta, as the benefactress of mankind. She furthers agriculture, law and order, apportions the fields, consecrates the land-marks, keeps and takes care of the souls of unborn children in her lovely gardens under the streams and lakes, and takes back there the souls of those who die young, that their mothers may cease to weep. As Holda or Dame Gode, she appears as a mighty huntress, devoted to the noble pursuit of the chase. The maidens of the northern Freya are called Siöfna, the lady of sighs; Lofna, whose work it is to bring lovers together in spite of every obstacle; and the wise Wara, who listens to the desire of each human heart, and avenges every breach of faith.

Thor or Thunar

whose turn it now is to be described, is the ideal of the German peasant, as untiring at work as in eating and drinking; open-hearted, therefore often deceived, but when made aware of the deception that has been practised on him, terrible in his wrath, and overthrowing his opponent with fierce and mighty blows.

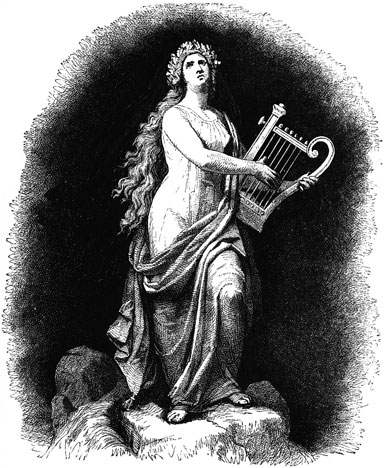

FRIGGA, ENGAGED IN HUNTING

He receives Miölnir, the storm-hammer, from the dwarfs who made it for him: he conquers Aiwis, the all-wise, in a battle of words. The giant Hrungnir pays for his temerity in challenging him to fight, with a broken head. When deceived by Utgard-Loki's magic, it is only want of opportunity, not of power, that prevents him taking vengeance. When he goes to the ice-giant Hymir to get the cauldron for brewing the beer for the feasts of the gods, he appears in all the fulness of his god-like power. Enveloped in Freya's bridal raiment, he gets back the stolen hammer from the mountain-giant Thrym, destroys the whole race of giants in Thrymheim, and makes the place over to his hard-working peasantry to till. He does the same at Geirödsgard after having overthrown the wily Geiröd. Although not to be withstood in his anger, he is yet mild and gracious when with his hammer he is fixing the landmarks, sanctifying the marriage bond, or consecrating the funeral-pile. Then he is the god who blesses law and order and every pious custom. For this reason he was deeply reverenced in all German and Scandinavian lands, and it is only the later skalds, as is seen in the Harbard lay, that make his glory less than that of the hero-god Odin.

Tyr, Tius, or Zio

- And now, tall and slender as a pine, brave Tyr comes forward. He has only one hand; for when the terrible Fenris-Wolf grew so powerful that he even threatened the gods themselves in Asgard, Tyr ventured to chain him up with bonds that could not be unloosed, and in so doing lost his hand. He bears a sword as his proper badge, for he is the god of war. The German people held him in high honour under the name of Tius or Zio.

Heru, Cheru or Saxnot

- Another naked sword flashes on the wooded heights in the land of the Cherusci; it is the weapon of the sword-god Heru, Cheru or Saxnot, who some think is no other than Tyr. Of this weapon Saga tells us that it causes the destruction of its possessor, should he be unworthy of owning it; but that in the hand of a hero it brings victory and sovereignty.

Heimdal or Riger

- The third sword god is known as Heimdal or Riger; he always appears with his sword girded to his side, and is the watchman stationed at the Bridge Bifröst to protect Asgard. He lives on his heavenly hill near the bridge, and drinks sweet mead all day. The faintest sounds are heard by him, and his piercing gaze penetrates even rocks and forests to the farthest distance. Then again he goes out into the world of men, and makes laws and ordinances. He blesses the human race, and keeps clear and visible the line of demarcation between the different classes.

Bragi and Iduna

- Heimdal is born of nine mothers, the wave-maidens, and Bragi also, the god of poetry, rises upon the waves from the depths of the sea. Nature receives him with rejoicing, and the blooming Iduna marries the divine bard. She accompanies him to Asgard, where she gives the gods every morning the apples of eternal youth.

The Wanes, Niörder, Freyer, Freya

- The Wanes are probably a race of gods who were worshipped by the earlier inhabitants of Germany and Scandinavia. Their war with the gods points back to the battles fought between these people and the invading Germanic races. At the conclusion of peace, the Prince of men, Niörder, his son bright Freyer, and his daughter Freya, are given as hostages to the gods, who on their side give up Mimir and Hönir to the Wanes. These Wanes rise to high honour and receive wide-spread adoration.

Fate, Norns, Hel, Walkyries

Orlog, Fate, a Power impossible to avoid or gainsay, rules over gods and men; it is impersonal, and bestows its gifts blindly. Out of the dense darkness surrounding it on every side, it also comes forth in visible shape as Regin, and guides and rules all things, and sometimes in the form of the gods, determines the life and actions of mortals. The Norns come out of the unknown distance enveloped in a dark veil, to the Ash Yggdrasil. They sprinkle it daily with water from the Fountain of Urd, that it may not wither, but remain green and fresh and strong. Urd, the eldest of the three sisters, gazes thoughtfully into the Past, Werdandi into the Present, and Skuld into the Future, which is either rich in hope or dark with tears. Thus they make known the decrees of Orlog, or Fate; for out of the past and present the events and actions of the future are born. Dark inscrutable Hel holds sway deep down in Helheim and Nifelheim. According to most ancient tradition she was once the earth-mother who watches over life and growth, and who finally calls the weary pilgrim home to her through the land of death.

In the poems of the skalds she becomes the dark, terrible Queen of the Realm of Shades, who brought death into the world. She has, however, no power over the course of battles where brave men struggle for the honour of victory. There Odin's Wish-maidens, the Walkyries, rule and determine the fate of the combatants. Armed with helmet and shield, they ride on white cloud horses to choose their warriors as the Father of the gods has commanded them. They consecrate the fallen heroes with the kiss of death, and bear them away to Walhalla to the feast of the Einheriar.

Ögir and his companions

Ögir or Hler moves about on the stormy seas accompanied by his wife Ran. Ögir is of the race of giants, but lives in friendly alliance with the gods. His comrades are the Mumel-king, the wonderful player, and the pixies, necks, and water-sprites.

Loki

the father of terrible Hel, the Fenris-Wolf and Midgard-Snake; Loki, the crafty god who is ever devising evil, now steals forward that we may observe his corrupt practices and his real character. In primeval times he was Odin's brother by blood, the god of life-giving warmth, and in particular of the indispensable household fire. As a destructive conflagration arises from a hidden spark which gradually increases in strength and volume, until at last it bursts out furiously and consumes the house and all that it contains, thus, as we shall show later on, the conception of Loki was developed in the minds of these old races, until he was at last held to be the corrupter of the gods, the principle of evil.

The other Gods

As regards the other gods, the silent Widar, son of Odin, first appears, armed with a sword and wearing iron shoes. Joyfully he hears the prophecy of the Norns, that he should on a future day avenge his father by killing the destroying wolf, and that he would afterwards live for ever in blissful peace in the renewed world. Then comes Hermodur, the swift messenger of the gods, who fulfils his office at a sign from Odin. Another avenger, the blooming Wali, is received with acclamation when he enters the halls of Odin, for he is the son of Odin and the northern Rinda, is chosen to avenge bright Baldur the well-beloved, and to give the deadly blow which shall send dark Hödur down to the realms of Hel. So the story brings us to Baldur, the giver of all good, and to Hödur, who rules over the darkness. The myth tells us how both fought for the sake of the lovely Nanna, and how the former received his death wound by magic art. His son Forseti, who resembles his father in holiness and righteousness, is the upholder of eternal law. The myth shows him to us seated on a throne teaching the Northern Frisians the benefits of law, and surrounded by his twelve judges, all of whom are somewhat like him both in face and form.

The Golden Age

From this brief glance at the individual gods we pass on to the description of the events which concern these divinities as a whole, and which lead up to the epic poems in which they figure. The golden age, the time of innocence, is next to be described, when the lust for gold was as yet unknown, when the gods played with golden disks, and no passion disturbed the rapture of mere existence. All this lasts till Gullweig (Gold-ore), the bewitching enchantress, comes, who, thrice cast into the fire, arises each time more beautiful than before, and fills the souls of gods and men with unappeasable longing. Then the Norns, the Past, Present and Future, enter into being, and the blessed peace of childhood's dreams passes away, and sin comes into existence with all its evil consequences.

Sin

The poems of the skalds give another account of the way in which sin makes its first appearance. The gods wish to have a strong wall of fortification round their Asgard, to protect it against the assaults of the Jotuns, the giants. Acting on Loki's advice, they swear by a holy oath to give the sun and moon, and even Freya herself, the goddess of grace and beauty, to an unknown builder, on condition that he finishes the wall in the course of one winter. The master-builder turns out to be a Hrimthurse (Frost-giant), who, with the help of his horse, seems about to finish the high wall of ice, the sides of which are as smooth as polished steel, within the allotted time. If the bargain were to hold good, darkness would envelop the world, and sweetness and love would disappear from life; so the gods command Loki, as he values his head, to tell them what to do. He outwits the giant by means of treachery and magic, and Thor pays the master-builder in blows of his hammer. Thus the gods break their oath, and inexpiable guilt rests upon them.

Iduna's departure

Evil portents precede the coming horrors. Iduna, the distributor of the apples of immortal youth, sinks from her bright home amid the boughs of the Ash Yggdrasil, into the gloomy depths below. She can only weep when the messengers ask her the meaning of her leaving them. Bragi remains with her, for with youth, games and song also pass away.

Baldur's death

The day of judgment approaches, and new signs bear witness of its coming. Baldur, the holy one, who alone is without sin, has terrible dreams. Hel appears to him in his sleep, and signs to him to come to her. Odin rides through the dark valleys which lead to the realm of shades, that he may enquire of the dead what the future will bring forth. His incantations call the long deceased Wala out of her grave, and she foretells what he has already feared, Baldur's death. Whereupon Frigga, who is much troubled in spirit, entreats all creatures and all lifeless things to swear that they will not injure the Well-beloved. But she overlooks one, the weak mistletoe-bough. Crafty Loki discovers this omission. When the gods in boisterous play throw their weapons at Baldur, all of which turn aside from striking his holy body, Loki gives blind Hödur the fatal bough, which he has made into a dart. He guides the direction of the blow, and the murder is committed - Baldur lies stabbed to the heart on the bloodstained sward. Peace and joy, righteousness and holiness disappear with him. For this reason the gods and men, and even the dwarfs who fear the light, the elves in their caverns, and the malicious race of giants weep for him. They all assemble round his funeral pile. Two corpses are stretched on the litter; for Nanna, Baldur's beautiful bride, has died of a broken heart. When the sunny-hearted god of light dies, the flowers must also wither. At Odin's command Hermodur rides along the road leading to Hel's dominions, to entreat the terrible goddess to permit the return of the Well-beloved. He finds Baldur and Nanna seated at a table on which are placed cups of mead, but they leave the foaming draught untouched; they sit there as silent and sad as the other flitting shades, which glide past them like misty phantoms. The dreadful queen of the realm of the dead is seated on her throne, grave and silent. This is her reply to Hermodur's message: "If every creature weeps for the Beloved he shall return to the upper world, otherwise he must remain in his place." The messenger of the gods brings back this answer. Every creature weeps for her son at Frigga's entreaty; but one giantess alone, dwelling in an obscure cleft in a rock, refrains from weeping, and so Baldur remains in Hel's possession. But vengeance has yet to be executed on the god who lives in darkness, and that duty is fulfilled by Wali, who kills strong Hodur with his darts. Wali is the god of spring, who destroys dark gloomy winter; he is the risen Baldur.

Ögir's banquet

The northern poems, apparently to break the course of these tragic events, now lead us to Ögir's palace, where the gods are assembled to hold a joyous feast after a long period of mourning. The hall is brilliantly lighted by the golden radiance of the treasures of the deep, and the tankards are full of foaming beer or mead; but the bard no longer sings to the music of the harp. Instead of that, Loki forces his way into the assembly; he does not now hide his wickedness under the cloak of hypocrisy, but openly boasts of what he has done. As the evildoer amongst men does not become a villain or a hardened criminal all at once, but gradually ascends the ladder of wickedness step by step until he reaches the summit, so it is with Loki; at first his actions are beneficial and good, then lie begins to give bad advice; after that he plots against the general peace, steals a costly treasure, and pitilessly works to bring about murder. At last he shows his diabolical nature without disguise, when, throwing aside the veil of hypocrisy, he hurls invectives at the gods, and openly acknowledges his horrible deeds of wickedness. The appearance of Thor forces him to take flight, and he barely escapes the dread hammer of the god.

Loki in chains

The murderer of Baldur, the blasphemer of the gods, cannot remain unpunished. In vain he conceals himself in a solitary house on a distant mountain, in vain he takes the form of a salmon and hides himself under a waterfall, for the avengers catch him in a peculiar net which he had formerly invented for the destruction of others. They bind him to the sharp ledge of a rock with the sinews of his son, which are changed into iron chains. A snake drops poison upon his face, making him yell with pain, and the earth quakes with his convulsive tremblings. His faithful wife Sigyn catches the poison in a cup; but still it drops upon him whenever the vessel is full.

Ragnarök

The destroyer lies in chains on the sharp ledge of rock; but he is not bound for ever. When the salutary bonds of law are broken, when discipline and morality, uprightness and the fear of God vanish, destruction comes upon states and nations. This is what is to happen at the time of which the legend now tells us. Nothing good or holy is respected. Falsehood, perjury, fratricidal wars, earthquakes, Fimbul-Winter (such severe winter as was never known before), are to be the signs that the end of the world is near. The sun and moon will be extinguished by their pursuers, the stars fall from the heavens, Yggdrasil will tremble, all chains be broken, and Loki and his dread sons be freed. Then the fiery sons of Muspel with dark Surtur at their head come from the South, and the giants from the East; the last battle shall be fought on the field of Wigrid. There the enemy's forces are drawn up in battle array, and thither Odin goes to meet them with his host of gods, and his band of Einheriar. And now the mountains fall down, the abyss yawns showing the very realms of Hel, the heavens split open and are lost in chaos, the chief warriors, the strong, are all slain in that deadly fight. Surtur, terrible to look upon, raises himself to the very sky; he flings his fiery darts upon the earth, and the universe is all burnt up. Our forefathers' conceptions as to the last battle, the single combats of the strong, the burning of the world, are all to be learnt from ancient traditions, as we find them described in the poems of the skalds.

The Renewal of the World

The myth compensates for the tragic end of the divine drama by concluding with a description of the renewal of the world. The earth rises green and blooming out of its ruin, as soon as it has been thoroughly purged from sin, refined and restored by fire. The gods assemble on the plains of Ida, the gods Widar and Wali are there, with Magni and Modi, the sons of Thor, who bring with them their father's Miölnir, a weapon no longer used for striking, but only for consecrating what is right and holy. They are joined by Baldur and Hödur, who are now reconciled, and united in brotherly love.

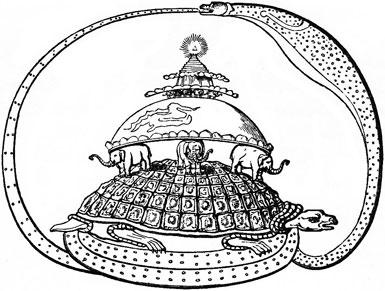

ANCIENT HINDU IDEA OF THE WORLD

From the drawing of a BrahminHuman beings are also to be found there, Lif and Lifthrasir, who, hidden in Hoddmimir's wood, dreamed the dreams of childhood, while the horrors of the last battle were taking place, and who, being pure and innocent and free from sinful desires, are permitted to enter the world where peace now reigns.

We have thought it requisite, for the better understanding of our history, to throw a cursory glance over the whole of the great drama, which describes to us the creation, prime, fall, destruction, and restoration of the world and the gods. The separate parts of the drama are not always connected with one another; they have grown up gradually in the course of centuries, and therefore are not calculated to fit into each other. Sometimes, indeed, they are in complete opposition to each other; yet in spite of this, one fundamental idea runs through all myths: we find in all that sin causes universal destruction, and that the world, purified by fire, rises again more beautiful and glorious than before. We have classified the myths as much as possible in accordance with this leading idea, and have also added their interpretations.

A good many parts of the Edda have, most likely, arisen in the land of the Cherusci, in Osning or Asening, and have been founded on songs in honour of the gods and heroes worshipped there. Moreover, it is an undoubted fact that the Northern skalds translated those songs, changing partially their form, and incorporating them with their own poems, so that the whole gained a northern colouring.

LAY OF THE NORSE GODS AND HEROES

Step out of the misty veil

Which darkly winds round thee;

Step out of the olden days,

Thou great Divinity!

Across thy mental vision

Passes the godly host,

That Bragi's melodies

Made Asgard's proudest boast.

AFTER PROF. ENGELHARD'S STATUE

There rise the sounds of music

From harp strings sweet and clear,

Wonderfully enchanting

To the receiving ear.

Thou wast it, thou hast carried

Sagas of northern fame,

Did'st boldly strike the harp strings

Of old skalds; just the same

Thou spann'st the bridge of Bifröst,

The pathway of the gods; -

O name the mighty heroes,

Draw pictures of the gods!

Let the reader now follow us into the world of Germanic gods, giants, dwarfs, and heroes. These fairy tales are not senseless stories written for the amusement of the idle; they embody the profound religion of our forefathers, which excited them to brave deeds, inspired them with strength and courage enough to shatter the Roman Empire, and to set up a new order of things in its stead. But when four hundred years after their dreadful battles against Germanicus, the Teutons victoriously entered their new country, the old faith had already faded, and they exchanged without difficulty their hero-god for St. Martin or the archangel Michael, and their Thunar for St. Peter or St. Oswald. The Saxons alone, in whose land the much revered holy places were to be found, clung to their gods, and when they were afterwards conquered by Charles the Great, some of them fled the country, carried their old religion to their northern brothers, and preserved it, until, at the time of the Wiking wars, it lost its glory in Scandinavia, and fell before the preaching of the Cross.