Asgard and the Gods

The Tales and Traditions of Our Northern Ancestors

First Part - Creation of the world

In the beginning was a great abyss; neither day nor night existed; the abyss was Ginnungagap, the yawning gulf, without beginning, without end. Allfather, the Uncreated, the Unseen, dwelt in the depth of the abyss and willed, and what he wilted came into being. Towards the north, in immeasurable space where dwell darkness and icy cold, arose Nifelheim (the Home of the Mists), and to the south was Muspelheim (the Home of Brightness), fiery, glowing with intense heat. The spring Hwergelmir (the seething cauldron) sprang into life in Nifelheim, and out of it flowed twelve and more infernal streams (Eliwagar) with their ice-cold waters. The dreadful cold soon froze the waters, and blocks of ice rolled over and under each other through the boundless gulf towards the south and Muspelheim. In the air above, the storms roared from Nifelheim, rooting up the icebergs; while from the Home of Brightness rays of beneficent heat poured forth over Ginnungagap, and when the great blocks of ice began to melt under the influence of this warmth, and drops of water to form and run down their sides, then it was that life first showed itself, and there arose a monster, the giant Ymir, or Örgelmir (seething clay), terrible to look upon. From him are descended the Hrimthurses or Frost-giants.

The warm rays awakened more life in the waters. The cow Audumla, the nourisher, came into being; from her flowed four streams of milk which fed the dreadful Ymir and his children, the Hrimthurses. But she had nothing to graze on except the salt of the ice-rocks, which she licked. On the first day after she had licked the rock, a head of hair was visible; on the second day, the whole head ; and on the third, the rest of the body, beautiful and glorious of limb. This was now Buri (the Producer), who had a son named Bör (born), and Bör married Bestla, daughter of the Hrimthurses, by whom he had three sons, Odin (spirit), Wili (will) and We (holy).

After this, war was made on the violent Ymir, and the sons of Bör slew him, and flung his great body into Ginnungagap, which was filled with it. But the blood of the monster flowed out covering all things, so that there was a great flood (Deluge) in which the Hrimthurses were drowned. One of them alone, the wise Bergelmir, saved himself and his wife from destruction by taking refuge in a cunningly made boat, and he became the father of the race of giants. This is the northern version of the story of Noah.

Space was now void and drear, as we learn from an ancient German lay: -

"I regarded among men as the greatest of wonders,

That the earth was not, nor yet the firmament,

Nor was there yet a tree, nor mountain, nor even sunshine,

Nor moon so radiant, nor ever a mighty sea."

The new rulers, who called themselves Ases, i.e., pillars and supports of the world, did not like this state of things at all. So they began to create as Allfather willed that they should. They made the earth of Ymir's body, the sea of his sweat, the hills of his bones, and the trees of his curly hair. Of his skull they made the firmament, and of his brain the clouds which float below. Then, out of the giant's eyebrows the gods formed Midgard (Middle-garden), the dwelling-place of the children of men, who as yet unborn slept in the lap of time.

Darkness reigned throughout space; only a few fiery sparks from Muspelheim wandered aimlessly through the air; the sun did not know her place, nor the moon his* course, nor did the stars know where they were to stand. But the gods collected the sparks, made them into stars and fastened them in the firmament.

* In German the sun is feminine, the moon masculine.

DAY

They created the chariot of the sun, harnessed to it the horse Arwaker (Early-waker), which was driven by the maiden Sol; she was rapidly followed by the shining moon drawn by the horse Alswider (All-swift), bridled and managed by the beautiful boy Mani. Mother Night talked lovingly to Mani as she preceded him on her dark horse Hrimfaxi (Frost-mane), whilst her son Day followed her with his bright Skinfaxi (Shining-mane).

Creatures of all sorts crept like maggots in and out of Ymir's

body and bones. The gods therefore consulted together as to what

was best to be done, and they thought that their wisest course

would be to change these creatures into a useful people. So they

at once changed them into Dwarfs and Trolls, who were gifted with

a wonderful knowledge of minerals and stones of all kinds, and an

extraordinary power of working in metals. One class of dwarfs was

of dark complexion, cunning and treacherous; the other was fair,

good and useful to gods and men.

NIGHT

Three mighty gods once left the place where the Thing or council was held; they were Odin, Hönir or Hahnir (the Bright One) and Lodur. While wandering over the face of the earth, which was green with grass and with the juicy leek, they found two human forms lying near the shore, Ask (the ash), and Embla (the alder), both of whom were without power or sense, motionless, colourless. Odin gave them souls; Honir, motion and the senses; and Lodur, blood and blooming complexions. From these two are descended all the numerous races of men.

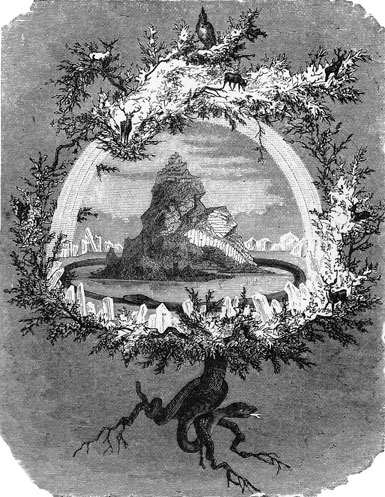

Allfather dwelt in the deep and willed, and what he willed came to pass. Then the ash Yggdrasil grew up, the tree of the universe, of time and of life. The boughs stretched out into heaven; its highest point, Lärad (peace-giver) overshadowed Walhalla, the hall of the heroes. Its three roots reached down to dark Hel, to Jotunheim the land of the Hrimthurses, and to Midgard the dwelling-place of the children of men. The World-tree was ever-green, for the fateful Norns sprinkled it daily with the water of life from the fountain of Urd which flowed in Midgard, But the goat Heidrun, from whom was obtained the mead that nourished the heroes, and the stag Eikthyrnir browsed upon the leaf-buds, and upon the bark of the tree, while the roots down below are gnawed by the dragon Nidhögg and innummerable worms : still the ash could not wither until the Last Battle should be fought, where life, time and the world were all to pass away. So the eagle sang its song of Creation and Destruction on the highest branch of the tree.

This is what a skald, a Northern bard, related to the warriors

who were resting from the fatigue of fighting, by tables of mead.

He and his comrades, intoxicated with the divine mead of

enthusiasm, used to tell these stories to the listening people.

The myths were founded on the belief of the Norse people

regarding the creation of the world, gods and men, and as such we

find them preserved in the Songs of the Edda. At the same time

the catastrophe is hinted at by which, in the opinion of these

races, the great world-drama was to end. It is true that many

unlovely and even coarse ideas are to be found mixed up with the

rest, and that they cannot be compared with the beautiful fancies

of Hellenic poetry; but the drama as a whole is grand and

philosophical, and had its birth in that heroic spirit which

forced the Teutons and Northern Wikings out into their battles of

life or death. We have also the idea of Allfather, the

unquestionable original cause of all things, though he is

scarcely more than mentioned in the poems.

THE ASH YGGDRASIL

This idea came more prominently forward in later times, but could not grow to its full proportions, because the preaching of the Gospel soon afterwards did away with the old faith. Whilst struggling against the horrors of a northern climate and sending out armies into distant land, the Teutons fixed their eyes on certain aspects of nature, and could not rise to distinct conceptions of the Eternal. Still this idea lay originally at the foundation of the Northern religion, and the kindred Aryan race in India developed and exhibited it in a wonderful and poetical manner.

Neither in the one case nor in the other, did the myths arise complete and perfect in the minds of these kindred people in the form in which we read them in the ancient documents. They needed a long time, a long period of development, before they appeared as regular myths or mythical tales. We must try to make clear to ourselves the process of the formation and development of the myth. Nations, like individuals, have their childhood, youth, prime and old age. In their childhood they cannot look upon the inexplicable facts and manifestations of the forces of nature, and on those of their own soul, otherwise than under certain forms. Nature, on which they feel themselves dependent, seems to them a Personality possessed of thought, will and perception. Nature is the Divinity they worship; she is the Self-existent Power of the Indian Aryans, the Eros of the Hellenes in their earliest home by the Acherusian Lake, and the Allfather who dwelt less clearly in the mind of the Germanic races. Amongst the Greeks the first departure from their earliest religious conceptions was the deification of Gaia, the all-nourishing earth; amongst the Hindus and Teutons, it was that of the shining firmament with its stars, its moon, its life-giving sun and its clouds with their refreshing rains.

The vague notion of a deity who created and ruled over all things had its rise in the impression made upon the human mind by the unity of nature, but was soon overcome by that produced by certain particular aspects of nature. The sun, moon and stars, clouds and mists, storms and tempests, appeared to be higher powers, and took distinct forms in the imagination of man. The sun was regarded now as a fiery bird which flew across the sky, now as a horse and now as a chariot and horses; the clouds were cows from whose udders the fruitful rain poured down, or nursing mothers, or heavenly streams and lakes; the storm-wind appeared as a gigantic eagle that stirred the air by the flapping of his great wings. As the phenomena of nature seemed to resemble animals either in outward form or in action, they were represented under the figure of animals. The beast which does not think, and which yet acts in accordance with some incomprehensible impulse, appears to be something extraordinary, something divine.

After riper consideration, it was discovered that man alone was gifted with the higher mental powers. It was therefore acknowledged that the figure of an animal was an improper representation of a divine being. Thus in inverted relation to that described in Holy Writ, when "God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him," men now made the gods in their own likeness, but at the same time regarded them as greater, more beautiful and more ideal than themselves.

The monotheistic idea of Allfather, which formed the basis of the Germanic religion, soon gave place to that of a trilogy, consisting at first of Odin, Wili and We, and afterwards of Odin, Hönir and Lodur. From these proceed the twelve gods of heaven, and they again are associated with many other divinities.

Polytheism has its origin in a variety of causes. The primary reason for it is to be found in the numerous qualities attributed to each one god, and also in his varying spheres of action. Hence the many additional names bestowed upon him. In course of time his identity with nature is forgotten, and people grow accustomed to accept his attributes as so many separate personalities. Thus, for instance, the powerful storm-god Wodan, the Northern Odin, was regarded as the highest god, the king of heaven. He it was who inspired both warlike and poetical enthusiasm. But still, the dispossessed king of heaven, Tyr, was worshipped as the god of war, while the art of poetry was placed under the protection of the divine Bragi, who was unknown in earlier times. Freya, the goddess of beauty and love, was essentially the same as the goddess of Earth, yet the German Nerthus and the Northern Jord and Rinda were honoured as such; from Freya was also derived Frigg, the queen of heaven, who was raised to the position of Odin's lawful wife. Another cause of the increase of the number of divinities is attributable to the vast extent of country over which the great Germanic race was spread, viz., over Germany, Scandinavia, and far away to the east amongst the Russian steppes. The numerous tribes into which the race was divided was another circumstance in favour of polytheism. These tribes preserved their language and their faith as a whole, but each had its own distinctive peculiarities and its own particular tribal god. They were sometimes communicated to other tribes, and in times of war the conquerors either dethroned the gods of the vanquished or else accepted them in addition to their own.

The divine kingdom as described in the legends of the gods and heroes

After the gods, the giants and the dwarfs had become personalities capable of free action; they were supposed to have stood in human relation to each other. They were given family ties and were finally brought under the laws of a divine kingdom. As people had now forgotten that the origin of the gods was to be found in the phenomena of nature, other motives for their fate and actions had to be sought, and thus the myth was added to, was made of wider significance, and its former meaning completely altered.

During the centuries that were necessary to bring about this development, there had been many changes in the fortunes of the Germanic tribes. They had destroyed the Roman empire, and had made their dwelling amongst its ruins. After that the proud victors bent their heads beneath the Cross, and accepted the Christian faith. Then the teaching of the Cross gradually made its way into Germany, the home of these warlike tribes; the messengers who brought it endeavoured to root out all relics of heathenism, and when preaching was of no avail, the power of the already converted ruler was brought into play. Thus was the old religion expunged from Germany proper. Still remnants of it are to be found in popular customs and traditions, and in a few fragmentary writings which suffice to show us the connection between the religion of our fathers and that preserved in the northern mythology.

It was different in the north, in Scandinavia. The preachers of the Gospel did not make their way there until much later. In that land the warlike chieftains dwelt in their towers and castles surrounded by their retainers, drinking sweet mead and beer, or the foreign wine they had brought home from their campaigns. There the victorious warriors delighted to tell of their adventurous voyages and Wiking raids, of battles with ice-giants, with winds and waves, and with the men of the south. There the skalds sang their lays in honour of the gods and heroes, and formed the myths into an artistic whole, a world-drama, which a happy chance has preserved to us. How this was done we shall now proceed to show.

In the tenth century Harald Harfager (fair hair) was acknowledged King of the whole realm of Norway. Many of the Jarls and Princes, who had formerly been independent rulers, were too proud to bear the yoke of the conqueror, and set out in search of other homes. The brave Rollo and his followers conquered Normandy and Brittany in France, others of the emigrants settled in the Shetland and Faroe islands, while others again under Ingulf and Hörleif landed on the inhospitable coasts of Iceland, and cultivated and peopled the island as far as its severe climate would permit. These people carried with them from their native land the old songs of the skalds, which the fathers sang to their sons, and the sons again to their sons, passing them on to each new generation as a most precious heritage. It is true that Christianity was introduced into Iceland towards the end of the tenth century, but before that time the people had preserved the songs of their forefathers, first by means of very imperfect runes, and then by the use of letters which had been brought to them from other lands, besides which the Christian priests, who were mostly Icelanders, were far from wishing to destroy the old tales. Many of them went so far as to listen to the songs of the people and afterwards write them down, and thus these treasures were saved from oblivion both in Iceland and in the Faroe islands. It is believed that the learned Icelander, Sæmund the Wise (A.D. 1056-1133), compiled the Elder Edda, the first collection of these old songs, partly from oral tradition and partly from imperfect runic writings which had been copied in Latin characters. This collection, which is called Sæmund's Edda after its supposed compiler, contains first in the Wöluspa (Song of Wala) the mythical account given by the northern imagination of the creation of the world, of giants, of gods, of dwarfs, and of men; then there is a description of the Last Battle and of the destruction and renewal of the world; after that come songs about the adventures and journeys of the individual gods, and lastly others are given in honour of the Heroes, especially the Niflungs, Sigurd the slayer of the dragon Fafnir, and so on. The Younger Edda, a collection of the same kind, is supposed to have been compiled by Bishop Snorri Sturlason (A.D. 1178-1241), and for that reason generally goes by the name of the Snorra-Edda. It is for the most part written in prose, and serves as a commentary on the Elder Edda, but was originally meant more particularly for the instruction of the Icelandic skalds.

The Runic language and characters

The word rûna really means "secret"; runes are therefore "mysterious signs requiring an interpretation." The shape of the letters leads to the supposition that they were formed in imitation of the Phoenician alphabet. It is clear that the runes were, from various causes, regarded even in Germany proper as full of mystery and endowed with supernatural power.

After Ulphilas made a new alphabet for the Goths in the fourth century by ingeniously uniting the form of the Greek letters to that of a runic alphabet consisting of twenty-five letters which was nearly related to that of the Anglo-Saxons; the runes gradually died out more and more, and as Christianity spread, the Roman alphabet was introduced in place of the old Germanic letters.

The runes appear to have served less as a mode of writing than as a help to the memory; they were principally used to note down a train of thought, to preserve wise sayings and prophecies, and the remembrance of particular deeds and memorable occurrences. Tacitus informs us that it was also customary to cut beech twigs into small pieces and then throw them on a cloth which had been previously spread out for the purpose, and afterwards to read future events by means of the signs accidentally formed by the bits of wood as they lay on the cloth.

The heroic lays of the old time have died out, and the runes have with few exceptions been rooted out of our fatherland by priestly zeal which looked upon them as magical. Our knowledge of the full-toned, powerful language of our ancestors is therefore very imperfect. But we know that it belonged to the great Aryan branch, and was thus related to the noblest of the Aryan languages, the Sanscrit or holy tongue, and was rich in inflexions.

In the Chinese and Indo-Chinese languages the ancient poverty of expression is still to be found, and even at the present day we find in them monosyllabic roots placed next to each other with hardly a connecting link; in the Turanian language of Central Asia the people have endeavoured to express the association of their ideas by the use of suffixes, but these suffixes are in themselves complete words, and thus the combination is as distinctly visible as the separate strokes of the brush in a bad painting. The language of the Teutonic race had already got beyond that point before the different tribes set out on their wanderings in search of a new home. The added words had fused with the others, and were capable of expressing an unbroken current of thought. The language had been developed by means of the Sagas and songs which had been handed down amongst the people from generation to generation.