Asgard and the Gods

The Tales and Traditions of Our Northern Ancestors

The three fatal sisters played a prominent part in many German tales. They used to watch over springs of water, and to appear by the cradle of many a royal infant to give it presents. On such occasions two of them were generally friendly to the child, while the third prophesied evil concerning it. Sometimes the Norns were supposed to be one, and then they were called Urd; but they were oftener looked upon as many, especially as the twelve Urds. In the pretty story of the "Sleeping Beauty" thirteen fairies appear. The king invited twelve of them to the birthday feast given in honour of his little daughter. Eleven had endowed the child with intelligence, beauty, wealth, and other good gifts, when suddenly a thirteenth fairy entered unbidden and ordained that the princess should die early of the prick of a spindle. The twelfth now came forward and took some of the bitterness out of the terrible prophecy by saying that the girl should not die, but should fall into a sleep of a hundred years' duration, out of which she should at last awake when the right hour for setting her free should strike. This hour came when a young hero forced his way through the thorn hedge that surrounded her, and awoke the sleeper with a kiss of love.

Urd or Wurd is also connected with Hel, the goddess of death for the Past, being dead, falls into the nether world. Hel herself appears in the story as the Norn who span the irrefragable thread of fate, and in the German version of the tale in which the fatal sisters appear, she was the bad fairy whose name, Held, betrays her identity with the goddess.

The origin of the Norns is wrapped in mystery; while the dwarfs, who are at times somewhat difficult to distinguish from the elves, were, as we have seen, created by the gods.

Three kinds of dwarfs existed in northern mythology, Modsognir's folk, Durin's band, and Dwalin's confederacy of Lofar's race. Lofar is perhaps the same as Loki, the fire-god, for all the dwarfs needed his help in their subterranean labours.

In the old German poems we often find descriptions of dwarf-kings, who ruled over underground realms, and the Norse nations regarded Modsognir's and Durin's people as especially great and powerful, more, however, from their miraculous strength and knowledge of magic than from their having rule over any definite territory. The ideas respecting these deformed and goblin-like creatures, some writers state, are connected with the appearance of the Phoenicians in the North. Wherever these roving merchants went, they always endeavoured to get at the raw products of the countries they visited. They fished for the purple mussel on the shores of Greece and Asia Minor; they dug for gold in the rich auriferous veins they found in Lemnos, where a volcanic mountain was looked upon as the forge of Hephæstos, and also in the island of Thasos, and in the Pangean mountains. They mined for silver in Spain, in which country old shafts and passages, mining implements and even vaulted underground chapels have been discovered. In Ireland they dug for silver, in England for the much esteemed tin-ore, and in the North also, they undoubtedly worked in the nines, and had furnaces and smithies above ground for smelting and forging the minerals they obtained. It was very natural that a barbarous people should imagine the existence of the Kobolds, when they heard the noise of working and hammering, and saw the sooty figures of what seemed to be a short, weakly race emerging from the earth. They regarded the strangers as mighty and powerful, because their minds were deeply impressed by their magical surroundings, and by the excellent weapons, beautiful ornaments, and delicately fashioned works of art they made in their flaming furnaces. The shrewd craftsmen must often have brought disaster upon the simple-minded barbarians by their deceit and cunning, and the dwarfs were therefore considered false and treacherous, and every one was warned against their malice.

These features, however, might with equal probability apply to the former inhabitants of the country who had been dispossessed by the Germanic invaders, perhaps even better than to the Phoenicians. These people were of a much weaker race than their conquerors; they took refuge in lake-dwellings or in subterranean caverns, hid in the mines they themselves had made, forged utensils of all sorts, and often over-reached their invaders by the sharpness of their wits.

Poetry created out of these dwellers in holes and caves of the rock those fantastic beings called Dwarfs and Black-Elves, because they were black and grimy, and because they rummaged in the dark places of the earth, did smith's work, were learned in the black art, and treacherous. The gloomy world in which they lived was called the Home of the Black-Elves.

In Germany they were known under the same name, but slightly altered in form. Their ruler in the middle ages was King Goldemar, whose brother Alberich or Elberich, and the sly, thievish Elbegast, were even more celebrated in poetry than he. In England, these are represented by the light airy elves, who danced their rounds on the hill-sides and in the valleys, but who love best to haunt lonely green woodlands and groves, and here King Oberon and Queen Titania had their invisible palaces and gardens, to which men sometimes found the way, and of which they related the wonders to believing multitudes after their return. Whoever has a touch of poetry in his soul, and is in the habit of wandering through the woods in the still summer evening, can even now-a-days see the mist-like forms of the little people dancing merrily in the openings of the wood or by the banks of the murmuring brook.

Equally celebrated in tales and legends is Number Nip, the mighty king of the Riesengebirge, of whose, power many strange tales were told; until at last modern enlightenment forced him to retreat into his underground realm.

The Light-Elves were different from the Black-Elves. They lived in the Home of the Light-Elves, were fair and good, and somewhat resembled the elves, but were not so airy or ethereal as the spirits of the later fairy-world. There are no myths about these kindly beings, which is a clear proof that the difference between the Black and Light-Elves was originally unknown.

The elves were popularly believed to be spirit-like beings, who were deeply versed in magic lore, and who had charge of the growth of plants. Some of them lived under the earth and others in the water; they often entered into friendly alliance with mortals, and demanded their help in many of their difficulties, handsomely rewarding all who assisted them. They were not always ugly to look upon; indeed, their beauty was sometimes extraordinary, and whenever they showed themselves amongst men, they used to wear splendid ornaments of gold and precious stones. If ever any one of mortal birth approached them, while they were dancing their rounds at midnight in the light of the full moon, they would draw him within their circle, and he never returned again to his people. The dwarfs and elves possessed rings by means of which they discovered and gained for themselves the treasures of the earth; they gave their friends magic rings which brought good-luck to the owner as long as they were carefully preserved; but the loss of them was attended with unspeakable misery.

A Polish count once received a ring of this kind from a tiny mannikin, whom he had allowed to celebrate his marriage festivities in the state rooms of his castle. With this jewel on his finger he was lucky in all his undertakings; his estates prospered; his wealth became enormous. His son enjoyed the same good fortune, and his grandson also, who both inherited the talisman in turn. The last heir gained a prince's coronet and fought with distinction in the Polish army. He accidentally lost the ring while at play, and could never recover it, although he offered thousands of sovereigns for its restoration. From that moment his luck forsook him: locusts devoured his harvest; earthquakes destroyed his castles. It even seemed as if the disasters of his native land were connected with his, for the Russians now made good their entrance into the country, and when Suwarrow stormed Praga, the unhappy prince received a sabre-cut over one of his eyes. When somewhat recovered, but quite disfigured by his wound and almost in as wretched plight as a beggar, he reached his ancestral castle, and there he was crushed to death under the falling building on the very first night. Exactly a hundred years had elapsed since that fateful hour in which his ancestor had placed his halls at the disposal of the underground spirit!

Besides these rings, the dwarfs and wights, like the elves, had other valuable possessions, such as hoods of darkness, by means of which the mannikins became invisible, and girdles that made the wearer supremely beautiful.

This was the reason why so many noble knights were overmastered by love for beautiful elf-women; but the marriages which were thus contracted had always a sad ending, because the natures of husband and wife were too dissimilar, and because there can be no real bond between men and spirits. For the elves were also regarded as the souls of the dead, and it was therefore impossible that any alliance formed by them with the living could be happy.

GIANTS

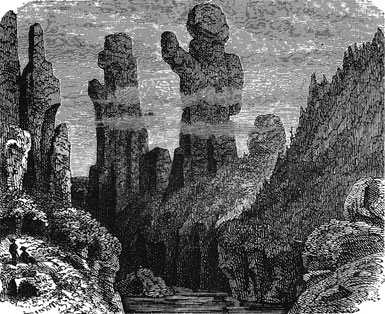

To the traveller passing through some desolate valley in the dusk or in a fog, the rocks jutting out from amongst the woods or ravines at his side seem to take strange, fantastic shapes. Not less spectral than these is the uncertain outline of the mountain tops, and especially of the bare granite or basaltic horns of rock which are scattered in great number over the face of the earth. In the old time, when man was more susceptible to impressions made by the life and working of nature, when he peopled the wilderness with the creatures of his own fancy, those dead stones appeared to him as living beings, moving about busily in the grey mist endowed in the dusk or moonlight with magic powers and approaching him as giants and monsters, but which were once more turned into stone as soon as they were touched by the first rays of the morning light.

These figures grew far more monstrous, far more weird in the great Alpine ranges and in Scandinavia. There the peaks, the ridges, and the ravines are covered with eternal ice and snow ; there the swollen, destructive mountain-torrents, growing glaciers, falling rocks and thundering avalanches, were regarded as the work of the infernal powers, the rime and frost-giants of northern legends. These evil beings are also to be found in the lower ranges of mountains. The Riesengebirge owe their name to them, while the Harz mountains were haunted by the Harz spirit and other demons.

Nearly related to these were the spirits of the storms and tempests, who came out of their dwellings in the clefts of the hills, massed up the storm-clouds, and spread destruction over the fields. The raging sea also was sometimes regarded as a giant, sometimes as a huge snake which encircled Midgard. As a snake they likewise personified those waters, which, breaking down the artificial breast-work man had built for their restraint, dashed and roared over the fruitful plains, engulfing towns, villages and their inhabitants in their course. The giant Logi (Flame), with his children and kindred, finally made themselves known as the authors of every great conflagration, when they might be seen in the midst of the flames, their heads crowned with chaplets of fire. These demons were all enemies of man, they strove to hinder his work and to destroy what he had made.

For the elements are hostile

To the work of human hand. -Schiller

Men therefore sought to propitiate them in ancient times by

offering them sacrifices, and consecrating altars and holy places

to them, until the moral powers, the gods, rose and fought

against them and their worship, but did not succeed in rooting

them out of the minds of the people.

ROCKS IN THE RIESENGEBIRGE

In the Greek myth, the rude destructive powers of nature, which were personified in the Titans and Giants, were completely overcome and abandoned; but in the North, where these forces are more wild and terrible, the struggle lasted until the Fire-giant Surtur, together with the sons of Muspel, set out for the Last Battle to destroy gods, men and worlds, and make place for a better order of things.

The legends of the giants and dragons were developed gradually, like all myths. At first natural objects were looked upon as identical with these strange beings, then the rocks and chasms became their dwelling-places, and finally they were regarded as distinct personalities, and had their own kingdom of Jotunheim. They showed themselves now in this place, now in that, and met gods and heroes in peace and in war. Perhaps they were not originally held to be wicked and altogether hostile, for springs and brooks flowed out of the earth for the refreshment of man and beast.

THE SLEEPING GIANT

They watered the fields so that they bore rich harvests; storms purified the air; the sea was an open roadway for ships, and the household fire, or the spirit which dwelt in it, was the most cheering companion of the Northman during his long winter evenings. But the thinking, ordering gods took their place, and then they only appeared as the wild unbridled forces of nature, against which man had to strive with the help of the heavenly powers.

In the North the giants were called Jotuns, signifying the voracious ones, and perhaps connected with the name of a German tribe, the Juten, that chased the aborigines out of Jutland. They were also called Thurses, i.e. the thirsty, the great drinkers. In Germany the giants were named Hünen, after their old enemies, the Huns. In Westphalia the gigantic grave-mounds and sacrificial places belonging to heathen times, that are to be found by the Weser and Elbe, are designated Huns' beds; and in the same way we recognise the Huns' rings. These are circular stone-walls, intended to enclose holy objects and consecrated spots of ground, in like manner as the dwellings of the gods are described in the Edda as surrounded by a fence or hedge.

Here in conclusion let us relate a myth made up of two kindred stories put together. We can still recognise the natural phenomena in the names.

From the first giant, Ymir, were descended three mighty sons Kari (air, storm), Hler (sea), and Logi (fire). Kari was the father of a numerous race, and his most powerful descendant, Frosti, ruled over a great empire in the far north. Now Frosti often made raids and incursions into neighbouring states, and on one occasion he went to Finland, where King Snär (snow) reigned. There he saw the king's daughter, fair Miöll (shining snow), and at once fell in love with her. But the haughty monarch refused him the hand of the maiden. He therefore sent a message to her secretly to tell her: "Frosti loves thee, and will share his throne with thee." To which she replied: "I love him also, and will await his coming by the sea-shore." Frosti appeared at the appointed time and took his bride in his strong arms. Meanwhile the plot had been discovered; Snär's fighting men lay in ambush to attack the lovers, and shot innumerable arrows at the bold warrior. But Frosti laughed at them all; the arrows fell from his silver armour like blunted needles, his storm horse broke through the ranks of the enemy and bore the lovers safely over the sea and over mountains and valleys to their Northern realm.

WORLDS AND HEAVENLY PALACES

"Nine homes I know, and branches nine,

Growing from out the stalwart tree

Down in the deep abyss."

This is the saying of Wala the prophetess, who sang of the creation, of the gods, and of the destruction of the world. She describes the Ash Yggdrasil as if the homes or worlds grew out of it like branches. Still the nine worlds are never enumerated in succession or in their full number, but are only to be distinguished by their characteristics.

In the centre of the universe the gods placed Midgard, the dwelling-place of man, and poured the sea all round it like a snake. They fortified it against the assaults of the sea and the inroads of the giants, by building a wall for its defence. The giants lived far away by the sea-shore in Jotunheim or Utgard, the giants' world. Above the earth was Wanaheim, the home of the wise shining Wanes, whom we shall describe further on. The Home of the Black-Elves was to be found under the earth, perhaps in those gloomy vales that led to the river which separated the realm of the dead from that of the living. This kingdom of the dead, Helheim, surrounded the Northern Mist-world, Nifelheim.

To the south was Muspelheim, where Surtur ruled with his flaming sword, and where the sons of Muspel lived. Over Midgard in the sunny nether was the Home of the Light-Elves, the friends of gods and men. Over the earth also, but higher than the Home of the Light-Elves, the gods founded their strong kingdom of Asgard, which shone with gold and precious stones, and where eternal spring reigned. The broad river Ifing divided the home of the gods from that of the Jotuns, but was not sufficient protection against the incursions of the giants, who were learned in magic.

The gods built themselves castles in Asgard, and halls that shone with gold. It is recorded that there were twelve such heavenly palaces, but the poems differ from each other in describing them.

High above Asgard was Hlidskialf (swaying gate), the throne of Odin, whence the all-ruling Father looked down upon the worlds and watched the doings of men, elves and giants. The palaces of the Ases were: Bilskirnir, the dwelling of Thor, 540 stories high and situated in his province of Thrudheim; Ydalir (yew-vale), where Uller, the brave bowman, lived; Walaskialf, the silver halls of Wali; Sökwabek, the dwelling of Saga (goddess of history), of which the Edda tells us: "Cool waters always flow over it, and in it Odin and Saga drink day after day out of golden beakers." In this palace the holy goddess Saga lived, and sang of the deeds of gods and heroes. She sang to the sound of the murmuring waters, until the flames of Surtur destroyed the nine homes and all the holy places. Then she rose and joined the faithful, who had escaped fire and sword, and fled with them to the North, to the inhabitants of Scandinavia. To these she sang in another tongue of the deeds of the Germanic heroes. But her songs did not pass away without leaving a trace behind; some of them are probably preserved in the Edda, and remain a treasure of poetry which can never be lost.

The fifth palace was called Gladsheim (shining-home); it belonged to the Father of the gods, and contained Walhalla, the hall of the blessed heroes, with its 500 doors. The whole shining building was enclosed within the grove Glasir of golden foliage. Thrymheim (thunder-home), where Skadi, daughter of the murdured giant Thiassi, lived, was originally supposed to be in Jotunheim, but the poems place it in Asgard.

Breidablick (wide out-look) was the dwelling of glorious Baldur, and in it no evil could be done. Heimdal, the watchman of the gods, lived in Himinbiörg (Heaven-hall), and there the blessed god drank sweet mead. Folkwang, the ninth castle, belonged to the mighty Freya. It was there that she brought her share of the fallen heroes from the field of battle. In Glitnir dwelt Forseti, the righteous, whose part it was to act as umpire, and smooth away all quarrels. Noatun was the castle of Niörder, the prince of men and protector of wealth and ships. Saga recognised as the twelfth heavenly palace Landwidi (broad-land), the dwelling of the silent Widar, son of Odin, who avenged his father's death in the Last Battle.

It is enough to say here regarding the mythological signification of these heavenly castles, that it is very probable that they were meant for the twelve constellations of the zodiac. For amongst these palaces none were allotted to the warrior god Tyr, nor do they count amongst their number Wingolf, the hall of the goddesses, or Fensal, the palace of Queen Frigga. According to this hypothesis the deities who possessed these twelve palaces were gods of the months. For instance, Uller, who lived at Ydalir, was the god of archery, and used to glide over the silvery ice-ways on skates. He ruled, in his quality of protector of the chase, when the sun passed over the constellation of Saggitarius in winter. Frey or Freya was called after him in the myth, and to him the gods gave, as a gift on his cutting his first tooth, the Home of the Light-Elves, which lies in the sun and is not to be found amongst the dwellings of Asgard.

The sun-god was also reborn at the time of the winter solstice, as Day was in the North. The Yule-feast was therefore celebrated in honour of the growing light with banquets and wine; Frey's boar was then sacrificed, and the drinking-horn was passed down the rows of guests. Wali's palace was, the story tells, covered with silver. By this the constellation of Aquarius was meant; when the sun passes over that part of the heavens where this constellation rules, it is a splendid sight in the far North to see the silvery sheen of the snow that covers the mountains and valleys. We refrain from further discussion of this theme, for these are only hypotheses, and myths of deeper meaning are awaiting us.