Chapter XXX: The Phæacians: Fate Of The Suiters

THE PHÆACIANS.

ULYSSES clung to the raft while any of its timbers kept together, and when it no longer yielded him support, binding the girdle around him, he swam. Minerva smoothed the billows before him and sent him a wind that rolled the waves towards the shore. The surf beat high on the rocks and seemed to forbid approach; but at length finding calm water at the mouth of a gentle stream, he landed, spent with toil, breathless and speechless and almost dead.

After some time, reviving, he kissed the soil, rejoicing, yet at a loss what course to take. At a short distance he perceived a wood to which he turned his steps. There, finding a covert sheltered by intermingling branches alike from the sun and the rain, he collected a pile of leaves and formed a bed, on which he stretched himself, and heaping the leaves over him, fell asleep.

Odysseus in the Court of Alcinous.

Francesco Hayez, 1813

The land where he was thrown was Scheria, the country of the Phæacians. These people dwelt originally near the Cyclopses; but being oppressed by that savage race, they migrated to the isle of Scheria, under the conduct of Nausithous, their king. They were, the poet tells us, a people akin to the gods, who appeared manifestly and feasted among them when they offered sacrifices and did not conceal themselves from solitary wayfarers when they met them.

They had abundance of wealth and lived in the enjoyment of it undisturbed by the alarms of war, for as they dwelt remote from gain–seeking men, no enemy ever approached their shores, and they did not even require to make use of bows and quivers. Their chief employment was navigation. Their ships, which went with the velocity of birds, were endued with intelligence; they knew every port and needed no pilot. Alcinous, the son of Nausithous, was now their king, a wise and just sovereign, beloved by his people.

Now it happened that the very night on which Ulysses was cast ashore on the Phæacian island, and while he lay sleeping on his bed of leaves, Nausicaa, the daughter of the king, had a dream sent by Minerva, reminding her that her wedding–day was not far distant, and that it would be but a prudent preparation for that event to have a general washing of the clothes of the family.

This was no slight affair, for the fountains were at some distance, and the garments must be carried thither. On awaking, the princess hastened to her parents to tell them what was on her mind; not alluding to her wedding–day, but finding other reasons equally good.

Her father readily assented and ordered the grooms to furnish forth a wagon for the purpose. The clothes were put therein, and the queen mother placed in the wagon, likewise, an abundant supply of food and wine. The princess took her seat and plied the lash, her attendant virgins following her on foot.

Arrived at the river side, they turned out the mules to graze, and unlading the carriage, bore the garments down to the water, and working with cheerfulness and alacrity, soon despatched their labour. Then having spread the garments on the shore to dry, and having themselves bathed, they sat down to enjoy their meal; after which they rose and amused themselves with a game of ball, the princess singing to them while they played. But when they had refolded the apparel and were about to resume their way to the town, Minerva caused the ball thrown by the princess to fall into the water, whereat they all screamed and Ulysses awaked at the sound.

Now we must picture to ourselves Ulysses, a shipwrecked mariner, but a few hours escaped from the waves, and utterly destitute of clothing, awaking and discovering that only a few bushes were interposed between him and a group of young maidens whom, by their deportment and attire, he discovered to be not mere peasant girls, but of a higher class.

Sadly needing help, how could he yet venture, naked as he was, to discover himself and make his wants known? It certainly was a case worthy of the interposition of his patron goddess Minerva, who never failed him at a crisis. Breaking off a leafy branch from a tree, he held it before him and stepped out from the thicket.

The virgins at sight of him fled in all directions, Nausicaa alone excepted, for her Minerva aided and endowed with courage and discernment.

Ulysses and Nausicaa by Pieter Pietersz Lastman

Ulysses, standing respectfully aloof, told his sad case, and besought the fair object (whether queen or goddess he professed he knew not) for food and clothing. The princess replied courteously, promising present relief and her father’s hospitality when he should become acquainted with the facts. She called back her scattered maidens, chiding their alarm, and reminding them that the Phæacians had no enemies to fear. This man, she told them, was an unhappy wanderer, whom it was a duty to cherish, for the poor and stranger are from Jove.

She bade them bring food and clothing, for some of her brothers’ garments were among the contents of the wagon. When this was done, and Ulysses, retiring to a sheltered place, had washed his body free from the sea–foam, clothed and refreshed himself with food, Pallas dilated his form and diffused grace over his ample chest and manly brows.

The princess, seeing him, was filled with admiration, and scrupled not to say to her damsels that she wished the gods would send her such a husband. To Ulysses she recommended that he should repair to the city, following herself and train so far as the way lay through the fields; but when they should approach the city she desired that he would no longer be seen in her company, for she feared the remarks which rude and vulgar people might make on seeing her return accompanied by such a gallant stranger. To avoid which she directed him to stop at a grove adjoining the city, in which were a farm and garden belonging to the king. After allowing time for the princess and her companions to reach the city, he was then to pursue his way thither, and would be easily guided by any he might meet to the royal abode.

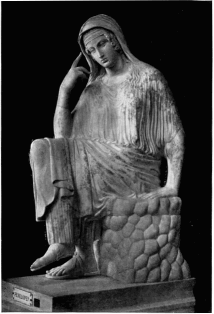

minerva. p. 130 1908 Edition

Ulysses obeyed the directions and in due time proceeded to the city, on approaching which he met a young woman bearing a pitcher forth for water. It was Minerva, who had assumed that form. Ulysses accosted her and desired to be directed to the palace of Alcinous the king. The maiden replied respectfully, offering to be his guide; for the palace, she informed him, stood near her father’s dwelling. Under the guidance of the goddess, and by her power enveloped in a cloud which shielded him from observation, Ulysses passed among the busy crowd, and with wonder observed their harbour, their ships, their forum (the resort of heroes), and their battlements, till they came to the palace, where the goddess, having first given him some information of the country, king, and people he was about to meet, left him.

Ulysses, before entering the courtyard of the palace, stood and surveyed the scene. Its splendour astonished him. Brazen walls stretched from the entrance to the interior house, of which the doors were gold, the doorposts silver, the lintels silver ornamented with gold. On either side were figures of mastiffs wrought in gold and silver, standing in rows as if to guard the approach. Along the walls were seats spread through all their length with mantles of finest texture, the work of Phæacian maidens. On these seats the princes sat and feasted, while golden statues of graceful youths held in their hands lighted torches which shed radiance over the scene.

Full fifty female menials served in household offices, some employed to grind the corn, others to wind off the purple wool or ply the loom. For the Phæacian women as far exceeded all other women in household arts as the mariners of that country did the rest of mankind in the management of ships.

Without the court a spacious garden lay, four acres in extent. In it grew many a lofty tree, pomegranate, pear, apple, fig, and olive. Neither winter’s cold nor summer’s drought arrested their growth, but they flourished in constant succession, some budding while others were maturing. The vineyard was equally prolific. In one quarter you might see the vines, some in blossom, some loaded with ripe grapes, and in another observe the vintagers treading the wine press. On the garden’s borders flowers of all hues bloomed all the year round, arranged with neatest art.

In the midst two fountains poured forth their waters, one flowing by artificial channels over all the garden, the other conducted through the courtyard of the palace, whence every citizen might draw his supplies.

Ulysses stood gazing in admiration, unobserved himself, for the cloud which Minerva spread around him still shielded him. At length, having sufficiently observed the scene, he advanced with rapid step into the hall where the chiefs and senators were assembled, pouring libation to Mercury, whose worship followed the evening meal.

Just then Minerva dissolved the cloud and disclosed him to the assembled chiefs. Advancing to the place where the queen sat, he knelt at her feet and implored her favour and assistance to enable him to return to his native country. Then withdrawing, he seated himself in the manner of suppliants, at the hearth side.

For a time none spoke. At last an aged statesman, addressing the king, said,

“It is not fit that a stranger who asks our hospitality should be kept waiting in suppliant guise, none welcoming him. Let him therefore be led to a seat among us and supplied with food and wine.”

At these words the king rising gave his hand to Ulysses and led him to a seat, displacing thence his own son to make room for the stranger. Food and wine were set before him and he ate and refreshed himself.

The king then dismissed his guests, notifying them that the next day he would call them to council to consider what had best be done for the stranger.

When the guests had departed and Ulysses was left alone with the king and queen, the queen asked him who he was and whence he came, and (recognizing the clothes which he wore as those which her maidens and herself had made) from whom he received those garments. He told them of his residence in Calypso’s isle and his departure thence; of the wreck of his raft, his escape by swimming, and of the relief afforded by the princess. The parents heard approvingly, and the king promised to furnish a ship in which his guest might return to his own land.

The next day the assembled chiefs confirmed the promise of the king. A bark was prepared and a crew of stout rowers selected, and all betook themselves to the palace, where a bounteous repast was provided. After the feast the king proposed that the young men should show their guest their proficiency in manly sports, and all went forth to the arena for games of running, wrestling, and other exercises.

After all had done their best, Ulysses being challenged to show what he could do, at first declined, but being taunted by one of the youths, seized a quoit of weight far heavier than any of the Phæacians had thrown, and sent it farther than the utmost throw of theirs. All were astonished, and viewed their guest with greatly increased respect.

After the games they returned to the hall, and the herald led in Demodocus, the blind bard,

“...Dear to the Muse,

Who yet appointed him both good and ill,

Took from his sight, but gave him strains divine.”

He took for his theme the “Wooden Horse,” by means of which the Greeks found entrance into Troy. Apollo inspired him, and he sang so feelingly the terrors and the exploits of that eventful time that all were delighted, but Ulysses was moved to tears. Observing which, Alcinous, when the song was done, demanded of him why at the mention of Troy his sorrows awaked. Had he lost there a father, or brother, or any dear friend? Ulysses replied by announcing himself by his true name, and at their request, recounted the adventures which had befallen him since his departure from Troy. This narrative raised the sympathy and admiration of the Phæacians for their guest to the highest pitch. The king proposed that all the chiefs should present him with a gift, himself setting the example. They obeyed, and vied with one another in loading the illustrious stranger with costly gifts.

The next day Ulysses set sail in the Phæacian vessel, and in a short time arrived safe at Ithaca, his own island. When the vessel touched the strand he was asleep. The mariners, without waking him, carried him on shore, and landed with him the chest containing his presents, and then sailed away.

Neptune was so displeased at the conduct of the Phæacians in thus rescuing Ulysses from his hands that on the return of the vessel to port he transformed it into a rock, right opposite the mouth of the harbour.

Homer’s description of the ships of the Phæacians has been thought to look like an anticipation of the wonders of modern steam navigation. Alcinous says to Ulysses,

“Say from what city, from what regions tossed,

And what inhabitants those regions boast?

So shalt thou quickly reach the realm assigned,

In wondrous ships, self-moved, instinct with mind;

No helm secures their course, no pilot guides;

Like man intelligently they plough the tides,

Conscious of every coast and every bay

That lies beneath the sun’s all-seeing ray.”

Odyssey, Book VIII.

[*]See; The Odyssey of Homer[*]

[*] See: Ulysses among the Phæacians[*]

Lord Carlisle, in his “Diary in the Turkish and Greek Waters,” thus speaks of Corfu, which he considers to be the ancient Phæacian island:

“The sites explain the ‘Odyssey.’ The temple of the sea–god could not have been more fitly placed, upon a grassy platform of the most elastic turf, on the brow of a crag commanding the harbour, and channel, and ocean. Just at the entrance of the inner harbour there is a picturesque rock with a small convent perched upon it, which by one legend is the transformed pinnace of Ulysses.

“Almost the only river in the island is just at the proper distance from the probable site of the city and palace of the king, to justify the princess Nausicaa having had resort to her chariot and to luncheon when she went with the maidens of the court to wash their garments.”

FATE OF THE SUITORS.

Ulysses had now been away from Ithaca for twenty years, and when he awoke he did not recognize his native land.

Minerva appeared to him in the form of a young shepherd, informed him where he was, and told him the state of things at his palace. More than a hundred nobles of Ithaca and of the neighbouring islands had been for years suing for the hand of Penelope, his wife, imagining him dead, and lording it over his palace and people, as if they were owners of both. That he might be able to take vengeance upon them, it was important that he should not be recognized. Minerva accordingly metamorphosed him into an unsightly beggar, and as such he was kindly received by Eumaeus, the swine–herd, a faithful servant of his house.

Telemachus, his son, was absent in quest of his father. He had gone to the courts of the other kings, who had returned from the Trojan expedition. While on the search, he received counsel from Minerva to return home.

He arrived and sought Eumaeus to learn something of the state of affairs at the palace before presenting himself among the suitors. Finding a stranger with Eumaeus, he treated him courteously, though in the garb of a beggar, and promised him assistance. Eumaeus was sent to the palace to inform Penelope privately of her son’s arrival, for caution was necessary with regard to the suitors, who, as Telemachus had learned, were plotting to intercept and kill him.

When Eumaeus was gone, Minerva presented herself to Ulysses, and directed him to make himself known to his son. At the same time she touched him, removed at once from him the appearance of age and penury, and gave him the aspect of vigorous manhood that belonged to him.

Telemachus viewed him with astonishment, and at first thought he must be more than mortal. But Ulysses announced himself as his father, and accounted for the change of appearance by explaining that it was Minerva’s doing.

“...Then threw Telemachus

His arms around his father’s neck and wept.

Desire intense of lamentation seized.

On both; soft murmurs uttering, each indulged

His grief.”

The father and son took counsel together how they should get the better of the suitors and punish them for their outrages. It was arranged that Telemachus should proceed to the palace and mingle with the suitors as formerly; that Ulysses should also go as a beggar, a character which in the rude old times had different privileges from what we concede to it now.

As traveller and storyteller, the beggar was admitted in the halls of chieftains, and often treated like a guest; though sometimes, also, no doubt, with contumely. Ulysses charged his son not to betray, by any display of unusual interest in him, that he knew him to be other than he seemed, and even if he saw him insulted, or beaten, not to interpose otherwise than he might do for any stranger. At the palace they found the usual scene of feasting and riot going on.

The suitors pretended to receive Telemachus with joy at his return, though secretly mortified at the failure of their plots to take his life. The old beggar was permitted to enter, and provided with a portion from the table. A touching incident occurred as Ulysses entered the courtyard of the palace. An old dog lay in the yard almost dead with age, and seeing a stranger enter, raised his head, with ears erect. It was Argus, Ulysses’ own dog, that he had in other days often led to the chase.

“...Soon as he perceived

Long-lost Ulysses nigh, down fell his ears

Clapped close, and with his tall glad sign he gave

Of gratulation, impotent to rise,

And to approach his master as of old.

Ulysses, noting him, wiped off a tear

Unmarked.

...Then his destiny released

Old Argus, soon as he had lived to see

Ulysses in the twentieth year restored.”

As Ulysses sat eating his portion in the hall, the suitors began to exhibit their insolence to him. When he mildly remonstrated, one of them raised a stool and with it gave him a blow. Telemachus had hard work to restrain his indignation at seeing his father so treated in his own hall, but remembering his father’s injunctions, said no more than what became him as master of the house, though young, and protector of his guests.

Penelope had protracted her

decision in favour of either of her suitors so long that there

seemed to be no further pretence for delay. The continued absence

of her husband seemed to prove that his return was no longer to

be expected. Meanwhile her son had grown up, and was able to

manage his own affairs. She therefore consented to submit the

question of her choice to a trial of skill among the suitors.

Penelope had protracted her

decision in favour of either of her suitors so long that there

seemed to be no further pretence for delay. The continued absence

of her husband seemed to prove that his return was no longer to

be expected. Meanwhile her son had grown up, and was able to

manage his own affairs. She therefore consented to submit the

question of her choice to a trial of skill among the suitors.

The test selected was shooting with the bow. Twelve rings were arranged in a line, and he whose arrow was sent through the whole twelve was to have the queen for his prize. A bow that one of his brother heroes had given to Ulysses in former times was brought from the armoury, and with its quiver full of arrows was laid in the hall. Telemachus had taken care that all other weapons should be removed, under pretence that in the heat of competition there was danger, in some rash moment, of putting them to an improper use.

All things being prepared for the trial, the first thing to be done was to bend the bow in order to attach the string. Telemachus endeavoured to do it, but found all his efforts fruitless; and modestly confessing that he had attempted a task beyond his strength, he yielded the bow to another.

He tried it with no better success, and, amidst the laughter and jeers of his companions, gave it up. Another tried it and another; they rubbed the bow with tallow, but all to no purpose; it would not bend. Then spoke Ulysses, humbly suggesting that he should be permitted to try; for, said he,

“beggar as I am, I was once a soldier, and there is still some strength in these old limbs of mine.”

The suitors hooted with derision, and commanded to turn him out of the hall for his insolence. But Telemachus spoke up for him, and, merely to gratify the old man, bade him try.

Ulysses took the bow, and handled it with the hand of a master. With ease he adjusted the cord to its notch, then fitting an arrow to the bow be drew the string and sped the arrow unerring through the rings.

Without allowing them time to express their astonishment, he said,

“Now for another mark!”

and aimed direct at the most insolent one of the suitors. The arrow pierced through his throat and he fell dead. Telemachus, Eumaeus, and another faithful follower, well armed, now sprang to the side of Ulysses.

The suitors, in amazement, looked round for arms, but found none, neither was there any way of escape, for Eumaeus had secured the door. Ulysses left them not long in uncertainty; he announced himself as the long–lost chief, whose house they had invaded, whose substance they had squandered, whose wife and son they had persecuted for ten long years; and told them he meant to have ample vengeance. All were slain, and Ulysses was left master of his palace and possessor of his kingdom and his wife.

Tennyson’s poem of “Ulysses” represents the old hero, after his dangers past and nothing left but to stay at home and be happy, growing tired of inaction and resolving to set forth again in quest of new adventures:

“...Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down;

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles whom we knew;” etc.

[*] See: The Bow of Ulysses [*]

[*] See; The Slaying of the Wooers [*]

[*]See: Ulysses by Tennyson [*]

[*] See: Telemachus, Penelope, and the Suitors [*]