From Stories From The Odyssey By H. L. Havell

Telemachus, Penelope, and the Suitors

I

In a high, level spot, commanding a view of the sea, stands the house of Ulysses, the mightiest prince in Ithaca. It is a spacious building, two storeys high, constructed entirely of wood, and surrounded on all sides by a strong wooden fence. Within the enclosure, and in front of the house, is a wide courtyard, containing the stables, and other offices of the household.

A proud maiden was Penelope, when Ulysses wedded her in her youthful bloom, and made her the mistress of his fair dwelling and his rich domain. One happy year they lived together, and a son was born to them, whom they named Telemachus. Then war arose between Greece and Asia, and Ulysses was summoned to join the train of chieftains who followed Agamemnon to win back Helen, his brother's wife. Ten years the war lasted; then Troy was taken, and those who had survived the struggle returned to their homes. Among these was Ulysses, who set sail with joyful heart, hoping, before many days were passed, to take up anew the thread of domestic happiness which had been so rudely broken. But since that hour he has vanished from sight, and for ten long years from the fall of Troy the house has been mourning its absent lord.

During the last three years a new trouble has been present, to fill the cup of Penelope's sorrow to the brim. A host of suitors, drawn from the most powerful families in Ithaca and the neighbouring islands, have beset the house of Ulysses, desiring to wed his wife and possess her wealth. All her friends urge her to make choice of a husband from that clamorous band; for no one now believes that there is any hope left of Ulysses' return. Only Penelope still clings to the belief that he is yet living, and will one day come home. So for three years she has put them off by a cunning trick. She began to weave a shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes, promising that, as soon as the garment was finished, she would wed one of the suitors. Then all day long she wove that choice web; and every night she undid the work of the day, unravelling the threads which she had woven. So for three years she beguiled the suitors, but at last she was betrayed by her handmaids, and the fraud was discovered. The princes upbraided her loudly for her deceit, and became more importunate than ever. The substance of Ulysses was wasting away; for day after day the wooers came thronging to the house, a hundred strong, and feasted at the expense of its absent master, and drank up his wine.

No hope seems left to the heartbroken, faithful wife. Even her son has grown impatient at the waste of his goods, and urges her to make the hard choice, and the hateful hour is at hand which will part her for ever from the scene of her brief wedded joy.

II

It was the hour of noon, and the sun was beating hot on the rocky hills of Ithaca, when a solitary wayfarer was seen approaching the outer gateway which led into the courtyard of Ulysses' house. He was a man of middle age, dressed like a chieftain, and carrying a long spear in his hand. Passing through the covered gateway he halted abruptly, and gazed in astonishment at the strange sight which met his eyes. All was noise and bustle in the courtyard, where a busy troop of servants were preparing the materials for a great feast. Some were carrying smoking joints of roast meat, others were filling huge bowls with wine and water, and others were washing the tables and setting them out to dry. In the portico before the house sat a great company of young nobles, comely of aspect, and daintily attired, taking their ease on couches of raw ox-hide, and playing at draughts to while away the time until the banquet should be ready. Loud was their talk, and boisterous their laughter, as of men who have no respect for themselves or for others. "Surely this was the house of Ulysses," murmured the stranger to himself, "but now it seems like a den of thieves. But who is that tall and goodly lad, who sits apart, with gloomy brow, and seems ill-pleased with the doings of that riotous crew? Surely I should know that face, the very face of my old friend as I knew him long years ago."

As he spoke, the youth who had attracted his notice glanced in his direction, and seeing a stranger standing unheeded at the entrance, he rose from his seat and came with hasty step and heightened colour towards him. "Forgive me, friend," he said, with hand outstretched in welcome, "that I marked thee not before. My thoughts were far away. But come into the house, and sit down to meat, and when thou hast eaten we will inquire the reason of thy coming."

So saying, and taking the stranger's spear, he led him into the great hall of the house, and sat down with him in a corner, remote from the noise of the revel. And a handmaid bare water in a golden ewer, and poured it over their hands into a basin of silver; and when they had washed, a table was set before them, heaped with delicate fare. Then host and guest took their meal together, and comforted their hearts with wine.

Before they had finished, the whole company came trooping in from the courtyard, and filled the room with uproar, calling aloud for food and drink. Not a chair was left empty, and the servants hurried to and fro, supplying the wants of these unwelcome visitors. Vast quantities of flesh were consumed, and many a stout jar of wine was drained to the dregs, to supply the wants of that greedy multitude.

When at last their hunger was appeased, and every goblet stood empty, Phemius, the minstrel, stood up in their midst, and after striking a few chords on his harp, began to sing a famous lay. Then the youth who had been entertaining the stranger drew closer his chair, and thus addressed him, speaking low in his ear: "Thou seest what fair company we keep, how wanton they are, and how gay. Yet there was once a man who would have driven them, like beaten hounds, from this hall, even he whose substance they are devouring. But his bones lie whitening at the bottom of the sea, and we who are left must tamely suffer this wrong. But now thou hast eaten, and I may question thee without reproach. Say, therefore, who art thou, and where is thy home? Comest thou for the first time to Ithaca, or art thou an old friend of this house, bound to us by ties of ancient hospitality?"

"My name is Mentes," answered the stranger, "and I am a prince of the Taphians, a bold race of sailors. I am a friend of this house, well known to its master, Ulysses, and his father, Laertes. Be of good cheer, for he whom thou mournest is not dead, nor shall his coming be much longer delayed. But tell me now of a truth, art not thou the son of that man? I knew him well, and thou hast the very face and eyes of Ulysses."

"My mother calls me his son," replied the youth, who was indeed Telemachus himself, "and I am bound to believe her. Would that it were otherwise! I have little cause to bless my birth."

"Yet shalt thou surely be blest," said Mentes; "thou art not unmarked of the eye of Heaven. But answer me once more, what means this lawless riot in the house? And what cause has brought all these men hither?"

"This also thou shalt know," replied Telemachus. "These are the princes who have come to woo my mother; and while she keeps them waiting for her answer they eat up my father's goods. Ere long, methinks, they will make an end of me also."

"Fit wooers indeed for the wife of such a man!" said Mentes with a bitter smile. "Would that he were standing among them now as I saw him once in my father's house, armed with helmet and shield and spear! He would soon wed them to another bride. But whether it be God's will that he return or not, 'tis for thee to devise means to drive these men from thy house. Take heed, therefore, to my words, and do as I bid thee. To-morrow thou shalt summon the suitors to the place of assembly, and charge them that they depart to their homes. And do thou thyself fit out a ship, with twenty rowers, and get thee to Pylos, where the aged Nestor dwells, and inquire of him concerning thy father. From Pylos proceed to Sparta, the kingdom of Menelaus; he was the last of the Greeks to reach home, after the fall of Troy; and perchance thou mayest learn something from him. And if thou hearest sure tidings of thy father's death, then get thee home, and raise a tomb to his memory, and keep his funeral feast. Then let thy mother wed whom she will; and if these men still beset thee, thou must devise means to slay them, either by guile or openly. Thou art now a man, and must play a man's part. Hast thou not heard of the fame which Orestes won, when he slew the murderer of his sire? Be thou valiant, even as he; tall thou art, and fair, and shouldst be a stout man of thy hands. But 'tis time for me to be going; my ship awaits me in the harbour, and my comrades will be tired of waiting for me."

"Stay yet awhile," answered Telemachus, "until thou hast refreshed thyself with the bath; and I will give thee a costly gift to bear with thee as a memorial of thy visit." But even as he spoke Mentes rose from his seat and, gliding like a shadow through the sunlit doorway, disappeared. Telemachus followed, in wonder and displeasure; but no trace of the strange visitor was to be seen. Looking upward he saw a great sea-eagle winging his way towards the shore; and a voice seemed to whisper in his ear: "No mortal was thy guest, but the great goddess Athene, daughter of Zeus, and ever thy father's true comrade and faithful ally."

III

With a strange elation of spirits Telemachus returned to the hall, and sat down among the suitors. Hitherto he had shown a certain weakness and indecision of character, natural in a young lad, who had grown up without the strong guiding hand of a father, and who, since the first dawn of his manhood, had been surrounded by a host of subtle foes. But the words of Athene have gone home, and he resolves that from this hour he will take his proper place in the house as his mother's guardian and the heir of a great prince.

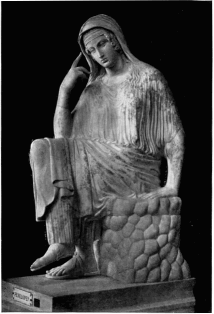

There was an unwonted stillness among that lawless troop, and they sat silent and attentive in the great, dimly lighted chamber. For the minstrel was singing a sweet and solemn strain, which told of the home-coming of the Greeks from Troy, and of all the disasters which befell them on the way. Suddenly the singer paused in the midst of his lay, for his fine ear had caught the sound of a sobbing sigh. Looking round, he saw a tall and stately lady standing in the doorway which led to the women's apartments at the back of the house. She was closely veiled, but he instantly recognised the form of Penelope, his beloved mistress.

"Phemius," said Penelope, in a tone of gentle reproach, "hast thou no other lay to sing, but must needs recite this tale of woe, which fills my soul with tears, by calling up the image of him for whom I sorrow night and day?"

Phemius stood abashed, and ventured no reply; but Telemachus answered for him. "Mother," he said, "blame not the sweet minstrel for his song. The bard is not the author of the woes of which he sings, but Zeus assigns to each his portion of good and ill; and thou must submit to his ordinance, like many another lady who has lost her lord. Thou hast thy province in the house, and I mine; thine is to govern thy handmaids, and mine to take the lead where the men are gathered together. And I say that the minstrel has chosen well."

There was a new note of command in the voice of Telemachus as he uttered these words. Penelope heard it, and wondered what change had come over her son; but a hundred bold eyes were gazing insolently at her, and without another word she turned away, and ascended the steep stairs which led to her bower. There she reclined on a couch, and her tears flowed freely; for the song of Phemius had reopened the fountain of her grief. Presently the sound of sobbing died away, and she drew her breath gently in a sweet and placid sleep.

The sudden appearance of Penelope had excited the suitors, and they began to brawl noisily among themselves. Presently Telemachus raised his voice, commanding silence for the minstrel. "And I have something else to say unto you," he added. "To-morrow at dawn I bid you come to the place of assembly, that we may make an end of these wild doings in my house. I will bear it no longer, but will publish your evil deeds to the ears of gods and men."

Among the suitors there was a certain Antinous, a tall and stout fellow, of commanding presence, who was looked up to by the others as a sort of leader, being the boldest and most brutal in the band. And now he answered for the rest "Heaven speed thy boasting, young braggart!" he cried in rude and jeering tones. "It will be a happy day for the men of Ithaca when they have thee for their king."

"I claim not the kingdom," answered Telemachus firmly, "but I am resolved to be master in my own house."

By the side of Antinous sat Eurymachus, who was next to him in power and rank. This was a smooth and subtle villain, not less dangerous than Antinous, but glib and plausible of speech. And he too made answer after his kind: "Telemachus, thou sayest well, and none can dispute thy right. But with thy good leave I would ask thee concerning the stranger. He seemed a goodly man; but why did he start up and leave us so suddenly? Did he bring any tidings of thy father?"

"There can be no tidings of him," answered Telemachus sadly, "except that we shall never see him again. And as to this stranger, it was Mentes, a friend of my father's, and prince of the Taphians."

Night was now coming on, the suitors departed to their homes, and Telemachus, who meditated an early start next day, retired early to his chamber. The room where he slept stood in the courtyard, apart from the house, and was reached by a stairway. He was attended by an aged dame, Eurycleia, who had nursed him in his infancy. And all night long he lay sleepless, pondering on the perils and the adventures which awaited him.