CHAPTER III.—STRATEGY.

Definition of Strategy and Tactics.

THE FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLE OF WAR.

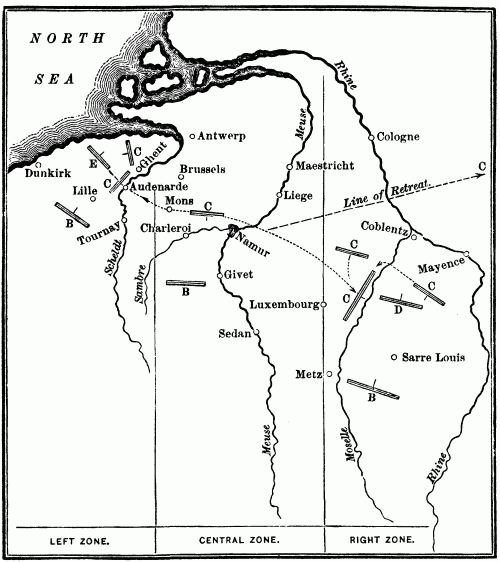

ART. XVI.—The System of Offensive

or Defensive Operations.

ART. XVII.—The Theater of

Operations.

ART. XVIII.—Bases of

Operations.

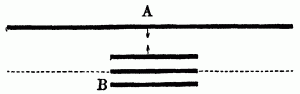

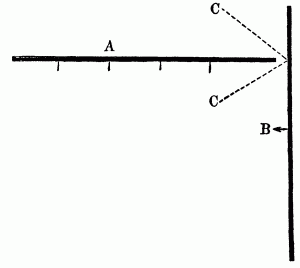

ART. XIX.—Strategic Lines and

Points, Decisive Points of the Theater of War, and Objective

Points of Operation.

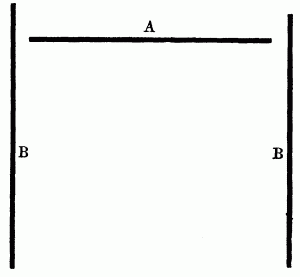

ART. XX.—Fronts of Operations,

Strategic Fronts, Lines of Defense, and Strategic

Positions.

ART. XXI.—Zones and Lines of

Operations.

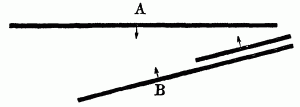

ART. XXII.—Strategic Lines of

Maneuver.

ART. XXIII.—Means of Protecting

Lines of Operations by Temporary Bases or Strategic

Reserves.

ART. XXIV.—The Old and New Systems

of War.

ART. XXV.—Depots of Supply, and

their Relations to Operations.

ART. XXVI.—Frontiers, and their

Defense by Forts and Intrenched Lines.—Wars of

Sieges.

ART. XXVII.—Intrenched Camps and

Têtes de Ponts in their Relation to Strategy.

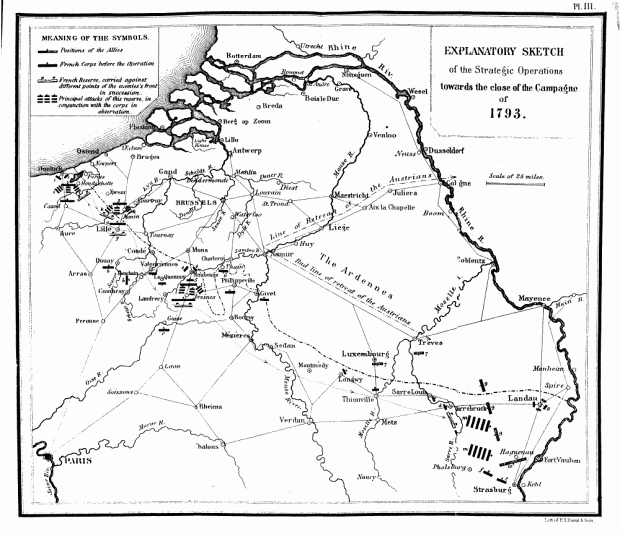

ART. XXVIII.—Strategic Operations

in Mountainous Countries.

ART. XXIX.—Grand Invasions and

Distant Expeditions.

Epitome of Strategy.

[Pg 11] CHAPTER IV. GRAND TACTICS

AND BATTLES.

CHAPTER V. SEVERAL OPERATIONS OF A MIXED

CHARACTER, WHICH ARE PARTLY IN THE DOMAIN OF STRATEGY AND PARTLY

OF TACTICS.

ART. XXXVI.—Diversions and

Great Detachments.

ART. XXXVII.—Passage of Rivers

and other Streams.

ART. XXXVIII.—Retreats and

Pursuits.

ART. XXXIX.—Cantonments and Winter

Quarters.

ART. XL.—Descents, or Maritime

Expeditions.

CHAPTER VI. LOGISTICS, OR THE PRACTICAL ART

OF MOVING ARMIES.

[Pg 12] CHAPTER VII. FORMATION AND

EMPLOYMENT OF TROOPS FOR BATTLE.

CONCLUSION.

SUPPLEMENT.

APPENDIX.

SECOND APPENDIX.

SKETCH OF

THE PRINCIPAL MARITIME EXPEDITIONS.

INDEX

[Pg 13]

SUMMARY

OF

THE ART OF WAR.

DEFINITION OF THE ART OF WAR.

The art of war, as generally considered, consists of five

purely military branches,—viz.: Strategy, Grand Tactics,

Logistics, Engineering, and Tactics. A sixth and essential

branch, hitherto unrecognized, might be termed Diplomacy in

its relation to War. Although this branch is more naturally

and intimately connected with the profession of a statesman than

with that of a soldier, it cannot be denied that, if it be

useless to a subordinate general, it is indispensable to every

general commanding an army: it enters into all the combinations

which may lead to a war, and has a connection with the various

operations to be undertaken in this war; and, in this view, it

should have a place in a work like this.

To recapitulate, the art of war consists of six distinct

parts:—

1. Statesmanship in its relation to war.

2. Strategy, or the art of properly directing masses upon the

theater of war, either for defense or for invasion.

3. Grand Tactics.

4. Logistics, or the art of moving armies.

5. Engineering,—the attack and defense of

fortifications.

6. Minor Tactics.

[Pg 14]It is proposed to analyze the principal

combinations of the first four branches, omitting the

consideration of tactics and of the art of engineering.

Familiarity with all these parts is not essential in order to

be a good infantry, cavalry, or artillery officer; but for a

general, or for a staff officer, this knowledge is

indispensable.

CHAPTER I.

STATESMANSHIP IN ITS RELATION TO WAR.

Under this head are included those considerations from which a

statesman concludes whether a war is proper, opportune, or

indispensable, and determines the various operations necessary to

attain the object of the war.

A government goes to war,—

To reclaim certain rights or to defend them;

To protect and maintain the great interests of the state, as

commerce, manufactures, or agriculture;

To uphold neighboring states whose existence is necessary

either for the safety of the government or the balance of

power;

To fulfill the obligations of offensive and defensive

alliances;

To propagate political or religious theories, to crush them

out, or to defend them;

To increase the influence and power of the state by

acquisitions of territory;

To defend the threatened independence of the state;

To avenge insulted honor; or,

From a mania for conquest.

It may be remarked that these different kinds of war influence

in some degree the nature and extent of the efforts and

operations necessary for the proposed end. The party who has

provoked the war may be reduced to the defensive, and the party

assailed may assume the offensive; and there [Pg 15]may be

other circumstances which will affect the nature and conduct of a

war, as,—

1. A state may simply make war against another state.

2. A state may make war against several states in alliance

with each other.

3. A state in alliance with another may make war upon a single

enemy.

4. A state may be either the principal party or an

auxiliary.

5. In the latter case a state may join in the struggle at its

beginning or after it has commenced.

6. The theater of war may be upon the soil of the enemy, upon

that of an ally, or upon its own.

7. If the war be one of invasion, it may be upon adjacent or

distant territory: it may be prudent and cautious, or it may be

bold and adventurous.

8. It may be a national war, either against ourselves or

against the enemy.

9. The war may be a civil or a religious war.

War is always to be conducted according to the great

principles of the art; but great discretion must be exercised in

the nature of the operations to be undertaken, which should

depend upon the circumstances of the case.

For example: two hundred thousand French wishing to subjugate

the Spanish people, united to a man against them, would not

maneuver as the same number of French in a march upon Vienna, or

any other capital, to compel a peace; nor would a French army

fight the guerrillas of Mina as they fought the Russians at

Borodino; nor would a French army venture to march upon Vienna

without considering what might be the tone and temper of the

governments and communities between the Rhine and the Inn, or

between the Danube and the Elbe. A regiment should always fight

in nearly the same way; but commanding generals must be guided by

circumstances and events.

To these different combinations, which belong more or less to

statesmanship, may be added others which relate solely to the

management of armies. The name Military Policy is [Pg 16]given

to them; for they belong exclusively neither to diplomacy nor to

strategy, but are still of the highest importance in the plans

both of a statesman and a general.

ARTICLE I.

Offensive Wars to Reclaim Rights.

When a state has claims upon another, it may not always be

best to enforce them by arms. The public interest must be

consulted before action.

The most just war is one which is founded upon undoubted

rights, and which, in addition, promises to the state advantages

commensurate with the sacrifices required and the hazards

incurred. Unfortunately, in our times there are so many doubtful

and contested rights that most wars, though apparently based upon

bequests, or wills, or marriages, are in reality but wars of

expediency. The question of the succession to the Spanish crown

under Louis XIV. was very clear, since it was plainly settled by

a solemn will, and was supported by family ties and by the

general consent of the Spanish nation; yet it was stoutly

contested by all Europe, and produced a general coalition against

the legitimate legatee.

Frederick II., while Austria and France were at war, brought

forward an old claim, entered Silesia in force and seized this

province, thus doubling the power of Prussia. This was a stroke

of genius; and, even if he had failed, he could not have been

much censured; for the grandeur and importance of the enterprise

justified him in his attempt, as far as such attempts can be

justified.

In wars of this nature no rules can be laid down. To watch and

to profit by every circumstance covers all that can be said.

Offensive movements should be suitable to the end to be attained.

The most natural step would be to occupy the disputed territory:

then offensive operations may be carried on according to

circumstances and to the respective strength of the parties, the

object being to secure the cession of the territory by the enemy,

and the means being to threaten [Pg

17]him in the heart of

his own country. Every thing depends upon the alliances the

parties may be able to secure with other states, and upon their

military resources. In an offensive movement, scrupulous care

must be exercised not to arouse the jealousy of any other state

which might come to the aid of the enemy. It is a part of the

duty of a statesman to foresee this chance, and to obviate it by

making proper explanations and giving proper guarantees to other

states.

ARTICLE II.

Of Wars Defensive Politically, and Offensive in a Military

Point of View.

A state attacked by another which renews an old claim rarely

yields it without a war: it prefers to defend its territory, as

is always more honorable. But it may be advantageous to take the

offensive, instead of awaiting the attack on the frontiers.

There are often advantages in a war of invasion: there are

also advantages in awaiting the enemy upon one's own soil. A

power with no internal dissensions, and under no apprehension of

an attack by a third party, will always find it advantageous to

carry the war upon hostile soil. This course will spare its

territory from devastation, carry on the war at the expense of

the enemy, excite the ardor of its soldiers, and depress the

spirits of the adversary. Nevertheless, in a purely military

sense, it is certain that an army operating in its own territory,

upon a theater of which all the natural and artificial features

are well known, where all movements are aided by a knowledge of

the country, by the favor of the citizens, and the aid of the

constituted authorities, possesses great advantages.

These plain truths have their application in all descriptions

of war; but, if the principles of strategy are always the same,

it is different with the political part of war, which is modified

by the tone of communities, by localities, and by the characters

of men at the head of states and armies. The fact of these

modifications has been used to prove that war knows no rules.

Military science rests upon principles which can [Pg 18]never

be safely violated in the presence of an active and skillful

enemy, while the moral and political part of war presents these

variations. Plans of operations are made as circumstances may

demand: to execute these plans, the great principles of war must

be observed.

For instance, the plan of a war against France, Austria, or

Russia would differ widely from one against the brave but

undisciplined bands of Turks, which cannot be kept in order, are

not able to maneuver well, and possess no steadiness under

misfortunes.

ARTICLE III.

Wars of Expediency.

The invasion of Silesia by Frederick II., and the war of the

Spanish Succession, were wars of expediency.

There are two kinds of wars of expediency: first, where a

powerful state undertakes to acquire natural boundaries for

commercial and political reasons; secondly, to lessen the power

of a dangerous rival or to prevent his aggrandizement. These last

are wars of intervention; for a state will rarely singly attack a

dangerous rival: it will endeavor to form a coalition for that

purpose.

These views belong rather to statesmanship or diplomacy than

to war.

ARTICLE IV.

Of Wars with or without Allies.

Of course, in a war an ally is to be desired, all other things

being equal. Although a great state will more probably succeed

than two weaker states in alliance against it, still the alliance

is stronger than either separately. The ally not only furnishes a

contingent of troops, but, in addition, annoys the enemy to a

great degree by threatening portions of his frontier which

otherwise would have been secure. All history teaches that no

enemy is so insignificant as to be despised and neglected by any

power, however formidable.

[Pg 19]

ARTICLE V.

Wars of Intervention.

To interfere in a contest already begun promises more

advantages to a state than war under any other circumstances; and

the reason is plain. The power which interferes throws upon one

side of the scale its whole weight and influence; it interferes

at the most opportune moment, when it can make decisive use of

its resources.

There are two kinds of intervention: 1. Intervention in the

internal affairs of neighboring states; 2. Intervention in

external relations.

Whatever may be said as to the moral character of

interventions of the first class, instances are frequent. The

Romans acquired power by these interferences, and the empire of

the English India Company was assured in a similar manner. These

interventions are not always successful. While Russia has added

to her power by interference with Poland, Austria, on the

contrary, was almost ruined by her attempt to interfere in the

internal affairs of France during the Revolution.

Intervention in the external relations of states is more

legitimate, and perhaps more advantageous. It may be doubtful

whether a nation has the right to interfere in the internal

affairs of another people; but it certainly has a right to oppose

it when it propagates disorder which may reach the adjoining

states.

There are three reasons for intervention in exterior foreign

wars,—viz.: 1, by virtue of a treaty which binds to aid; 2,

to maintain the political equilibrium; 3, to avoid certain evil

consequences of the war already commenced, or to secure certain

advantages from the war not to be obtained otherwise.

History is filled with examples of powers which have fallen by

neglect of these principles. "A state begins to decline when it

permits the immoderate aggrandizement of a rival, and a secondary

power may become the arbiter of nations if it throw its weight

into the balance at the proper time."

In a military view, it seems plain that the sudden

appear[Pg 20]ance of a new and large army as a third party in a

well-contested war must be decisive. Much will depend upon its

geographical position in reference to the armies already in the

field. For example, in the winter of 1807 Napoleon crossed the

Vistula and ventured to the walls of Königsberg, leaving

Austria on his rear and having Russia in front. If Austria had

launched an army of one hundred thousand men from Bohemia upon

the Oder, it is probable that the power of Napoleon would have

been ended; there is every reason to think that his army could

not have regained the Rhine. Austria preferred to wait till she

could raise four hundred thousand men. Two years afterward, with

this force she took the field, and was beaten; while one hundred

thousand men well employed at the proper time would have decided

the fate of Europe.

There are several kinds of war resulting from these two

different interventions:—

1. Where the intervention is merely auxiliary, and with a

force specified by former treaties.

2. Where the intervention is to uphold a feeble neighbor by

defending his territory, thus shifting the scene of war to other

soil.

3. A state interferes as a principal party when near the

theater of war,—which supposes the case of a coalition of

several powers against one.

4. A state interferes either in a struggle already in

progress, or interferes before the declaration of war.

When a state intervenes with only a small contingent, in

obedience to treaty-stipulations, it is simply an accessory, and

has but little voice in the main operations; but when it

intervenes as a principal party, and with an imposing force, the

case is quite different.

The military chances in these wars are varied. The Russian

army in the Seven Years' War was in fact auxiliary to that of

Austria and France: still, it was a principal party in the North

until its occupation of Prussia. But when Generals Fermor and

Soltikoff conducted the army as far as Brandenburg it acted

solely in the interest of Austria: the fate [Pg 21]of

these troops, far from their base, depended upon the good or bad

maneuvering of their allies.

Such distant excursions are dangerous, and generally delicate

operations. The campaigns of 1799 and 1805 furnish sad

illustrations of this, to which we shall again refer in Article XXIX., in discussing the military

character of these expeditions.

It follows, then, that the safety of the army may be

endangered by these distant interventions. The counterbalancing

advantage is that its own territory cannot then be easily

invaded, since the scene of hostilities is so distant; so that

what may be a misfortune for the general may be, in a measure, an

advantage to the state.

In wars of this character the essentials are to secure a

general who is both a statesman and a soldier; to have clear

stipulations with the allies as to the part to be taken by each

in the principal operations; finally, to agree upon an objective

point which shall be in harmony with the common interests. By the

neglect of these precautions, the greater number of coalitions

have failed, or have maintained a difficult struggle with a power

more united but weaker than the allies.

The third kind of intervention, which consists in interfering

with the whole force of the state and near to its frontiers, is

more promising than the others. Austria had an opportunity of

this character in 1807, but failed to profit by it: she again had

the opportunity in 1813. Napoleon had just collected his forces

in Saxony, when Austria, taking his front of operations in

reverse, threw herself into the struggle with two hundred

thousand men, with almost perfect certainty of success. She

regained in two months the Italian empire and her influence in

Germany, which had been lost by fifteen years of disaster. In

this intervention Austria had not only the political but also the

military chances in her favor,—a double result, combining

the highest advantages.

Her success was rendered more certain by the fact that while

the theater was sufficiently near her frontiers to permit the

greatest possible display of force, she at the same time

[Pg 22]interfered in a contest already in progress, upon

which she entered with the whole of her resources and at the time

most opportune for her.

This double advantage is so decisive that it permits not only

powerful monarchies, but even small states, to exercise a

controlling influence when they know how to profit by it.

Two examples may establish this. In 1552, the Elector Maurice

of Saxony boldly declared war against Charles V., who was master

of Spain, Italy, and the German empire, and had been victorious

over Francis I. and held France in his grasp. This movement

carried the war into the Tyrol, and arrested the great conqueror

in his career.

In 1706, the Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus, by declaring

himself hostile to Louis XIV., changed the state of affairs in

Italy, and caused the recall of the French army from the banks of

the Adige to the walls of Turin, where it encountered the great

catastrophe which immortalized Prince Eugene.

Enough has been said to illustrate the importance and effect

of these opportune interventions: more illustrations might be

given, but they could not add to the conviction of the

reader.

ARTICLE VI.

Aggressive Wars for Conquest and other Reasons.

There are two very different kinds of invasion: one attacks an

adjoining state; the other attacks a distant point, over

intervening territory of great extent whose inhabitants may be

neutral, doubtful, or hostile.

Wars of conquest, unhappily, are often prosperous,—as

Alexander, Cæsar, and Napoleon during a portion of his

career, have fully proved. However, there are natural limits in

these wars, which cannot be passed without incurring great

disaster. Cambyses in Nubia, Darius in Scythia, Crassus and the

Emperor Julian among the Parthians, and Napoleon in Russia,

furnish bloody proofs of these truths.—The love of

conquest, however, was not the only motive with Napoleon: his

personal position, and his contest with England, urged him to

enterprises the aim of which was [Pg

23]to make him supreme.

It is true that he loved war and its chances; but he was also a

victim to the necessity of succeeding in his efforts or of

yielding to England. It might be said that he was sent into this

world to teach generals and statesmen what they should avoid. His

victories teach what may be accomplished by activity, boldness,

and skill; his disasters, what might have been avoided by

prudence.

A war of invasion without good reason—like that of

Genghis Khan—is a crime against humanity; but it may be

excused, if not approved, when induced by great interests or when

conducted with good motives.

The invasions of Spain of 1808 and of 1823 differed equally in

object and in results: the first was a cunning and wanton attack,

which threatened the existence of the Spanish nation, and was

fatal to its author; the second, while combating dangerous

principles, fostered the general interests of the country, and

was the more readily brought to a successful termination because

its object met with the approval of the majority of the people

whose territory was invaded.

These illustrations show that invasions are not necessarily

all of the same character. The first contributed largely to the

fall of Napoleon; the second restored the relation between France

and Spain, which ought never to have been changed.

Let us hope that invasions may be rare. Still, it is better to

attack than to be invaded; and let us remember that the surest

way to check the spirit of conquest and usurpation is to oppose

it by intervention at the proper time.

An invasion, to be successful, must, be proportioned in

magnitude to the end to be attained and to the obstacles to be

overcome.

An invasion against an exasperated people, ready for all

sacrifices and likely to be aided by a powerful neighbor, is a

dangerous enterprise, as was well proved by the war in Spain,

(1808,) and by the wars of the Revolution in 1792, 1793, and

1794. In these latter wars, if France was better prepared than

Spain, she had no powerful ally, and she was attacked by all

Europe upon both land and sea.

Although the circumstances were different, the Russian

[Pg 24]invasion of Turkey developed, in some respects, the

same symptoms of national resistance. The religious hatred of the

Ottoman powerfully incited him to arms; but the same motive was

powerless among the Greeks, who were twice as numerous as the

Turks. Had the interests of the Greeks and Turks been harmonized,

as were those of Alsace with France, the united people would have

been stronger, but they would have lacked the element of

religious fanaticism. The war of 1828 proved that Turkey was

formidable only upon the frontiers, where her bravest troops were

found, while in the interior all was weakness.

When an invasion of a neighboring territory has nothing to

fear from the inhabitants, the principles of strategy shape its

course. The popular feeling rendered the invasions of Italy,

Austria, and Prussia so prompt. (These military points are

treated of in Article XXIX.) But when

the invasion is distant and extensive territories intervene, its

success will depend more upon diplomacy than upon strategy. The

first step to insure success will be to secure the sincere and

devoted alliance of a state adjoining the enemy, which will

afford reinforcements of troops, and, what is still more

important, give a secure base of operations, depots of supplies,

and a safe refuge in case of disaster. The ally must have the

same interest in success as the invaders, to render all this

possible.

Diplomacy, while almost decisive in distant expeditions, is

not powerless in adjacent invasions; for here a hostile

intervention may arrest the most brilliant successes. The

invasions of Austria in 1805 and 1809 might have ended

differently if Prussia had interfered. The invasion of the North

of Germany in 1807 was, so to speak, permitted by Austria. That

of Rumelia in 1829 might have ended in disaster, had not a wise

statesmanship by negotiation obviated all chance of

intervention.

[Pg 25]

ARTICLE VII.

Wars of Opinion.

Although wars of opinion, national wars, and civil wars are

sometimes confounded, they differ enough to require separate

notice.

Wars of opinion may be intestine, both intestine and foreign,

and, lastly, (which, however, is rare,) they may be foreign or

exterior without being intestine or civil.

Wars of opinion between two states belong also to the class of

wars of intervention; for they result either from doctrines which

one party desires to propagate among its neighbors, or from

dogmas which it desires to crush,—in both cases leading to

intervention. Although originating in religious or political

dogmas, these wars are most deplorable; for, like national wars,

they enlist the worst passions, and become vindictive, cruel, and

terrible.

The wars of Islamism, the Crusades, the Thirty Years' War, the

wars of the League, present nearly the same characteristics.

Often religion is the pretext to obtain political power, and the

war is not really one of dogmas. The successors of Mohammed cared

more to extend their empire than to preach the Koran, and Philip

II., bigot as he was, did not sustain the League in France for

the purpose of advancing the Roman Church. We agree with M.

Ancelot that Louis IX., when he went on a crusade in Egypt,

thought more of the commerce of the Indies than of gaining

possession of the Holy Sepulcher.

The dogma sometimes is not only a pretext, but is a powerful

ally; for it excites the ardor of the people, and also creates a

party. For instance, the Swedes in the Thirty Years' War, and

Philip II. in France, had allies in the country more powerful

than their armies. It may, however, happen, as in the Crusades

and the wars of Islamism, that the dogma for which the war is

waged, instead of friends, finds only bitter enemies in the

country invaded; and then the contest becomes fearful.

[Pg 26]The chances of support and resistance in wars of

political opinions are about equal. It may be recollected how in

1792 associations of fanatics thought it possible to propagate

throughout Europe the famous declaration of the rights of man,

and how governments became justly alarmed, and rushed to arms

probably with the intention of only forcing the lava of this

volcano back into its crater and there extinguishing it. The

means were not fortunate; for war and aggression are

inappropriate measures for arresting an evil which lies wholly in

the human passions, excited in a temporary paroxysm, of less

duration as it is the more violent. Time is the true remedy for

all bad passions and for all anarchical doctrines. A civilized

nation may bear the yoke of a factious and unrestrained multitude

for a short interval; but these storms soon pass away, and reason

resumes her sway. To attempt to restrain such a mob by a foreign

force is to attempt to restrain the explosion of a mine when the

powder has already been ignited: it is far better to await the

explosion and afterward fill up the crater than to try to prevent

it and to perish in the attempt.

After a profound study of the Revolution, I am convinced that,

if the Girondists and National Assembly had not been threatened

by foreign armaments, they would never have dared to lay their

sacrilegious hands upon the feeble but venerable head of Louis

XVI. The Girondists would never have been crushed by the Mountain

but for the reverses of Dumouriez and the threats of invasion.

And if they had been permitted to clash and quarrel with each

other to their hearts' content, it is probable that, instead of

giving place to the terrible Convention, the Assembly would

slowly have returned to the restoration of good, temperate,

monarchical doctrines, in accordance with the necessities and the

immemorial traditions of the French.

In a military view these wars are fearful, since the invading

force not only is met by the armies of the enemy, but is exposed

to the attacks of an exasperated people. It may be said that the

violence of one party will necessarily create support for the

invaders by the formation of another and op[Pg 27]posite

one; but, if the exasperated party possesses all the public

resources, the armies, the forts, the arsenals, and if it is

supported by a large majority of the people, of what avail will

be the support of the faction which possesses no such means? What

service did one hundred thousand Vendeans and one hundred

thousand Federalists do for the Coalition in 1793?

History contains but a single example of a struggle like that

of the Revolution; and it appears to clearly demonstrate the

danger of attacking an intensely-excited nation. However the bad

management of the military operations was one cause of the

unexpected result, and before deducing any certain maxims from

this war, we should ascertain what would have been the result if

after the flight of Dumouriez, instead of destroying and

capturing fortresses, the allies had informed the commanders of

those fortresses that they contemplated no wrong to France, to

her forts or her brave armies, and had marched on Paris with two

hundred thousand men. They might have restored the monarchy; and,

again, they might never have returned, at least without the

protection of an equal force on their retreat to the Rhine. It is

difficult to decide this, since the experiment was never made,

and as all would have depended upon the course of the French

nation and the army. The problem thus presents two equally grave

solutions. The campaign of 1793 gave one; whether the other might

have been obtained, it is difficult to say. Experiment alone

could have determined it.

The military precepts for such wars are nearly the same as for

national wars, differing, however, in a vital point. In national

wars the country should be occupied and subjugated, the fortified

places besieged and reduced, and the armies destroyed; whereas in

wars of opinion it is of less importance to subjugate the

country; here great efforts should be made to gain the end

speedily, without delaying for details, care being constantly

taken to avoid any acts which might alarm the nation for its

independence or the integrity of its territory.

The war in Spain in 1823 is an example which may be cited in

favor of this course in opposition to that of the Revolution. It

is true that the conditions were slightly different; [Pg 28]for

the French army of 1792 was made up of more solid elements than

that of the Radicals of the Isla de Leon. The war of the

Revolution was at once a war of opinion, a national war, and a

civil war,—while, if the first war in Spain in 1808 was

thoroughly a national war, that of 1823 was a partial struggle of

opinions without the element of nationality; and hence the

enormous difference in the results.

Moreover, the expedition of the Duke of Angoulême was

well carried out. Instead of attacking fortresses, he acted in

conformity to the above-mentioned precepts. Pushing on rapidly to

the Ebro, he there divided his forces, to seize, at their

sources, all the elements of strength of their

enemies,—which they could safely do, since they were

sustained by a majority of the inhabitants. If he had followed

the instructions of the Ministry, to proceed methodically to the

conquest of the country and the reduction of the fortresses

between the Pyrenees and the Ebro, in order to provide a base of

operations, he would perhaps have failed in his mission, or at

least made the war a long and bloody one, by exciting the

national spirit by an occupation of the country similar to that

of 1807.

Emboldened by the hearty welcome of the people, he

comprehended that it was a political operation rather than a

military one, and that it behooved him to consummate it rapidly.

His conduct, so different from that of the allies in 1793,

deserves careful attention from all charged with similar

missions. In three months the army was under the walls of

Cadiz.

If the events now transpiring in the Peninsula prove that

statesmanship was not able to profit by success in order to found

a suitable and solid order of things, the fault was neither in

the army nor in its commanders, but in the Spanish government,

which, yielding to the counsel of violent reactionaries, was

unable to rise to the height of its mission. The arbiter between

two great hostile interests, Ferdinand blindly threw himself into

the arms of the party which professed a deep veneration for the

throne, but which intended to use the royal authority for the

furtherance of its own ends, regardless of consequences. The

nation remained divided in two hostile [Pg

29]camps, which it

would not have been impossible to calm and reconcile in time.

These camps came anew into collision, as I predicted in Verona in

1823,—a striking lesson, by which no one is disposed to

profit in that beautiful and unhappy land, although history is

not wanting in examples to prove that violent reactions, any more

than revolutions, are not elements with which to construct and

consolidate. May God grant that from this frightful conflict may

emerge a strong and respected monarchy, equally separated from

all factions, and based upon a disciplined army as well as upon

the general interests of the country,—a monarchy capable of

rallying to its support this incomprehensible Spanish nation,

which, with merits not less extraordinary than its faults, was

always a problem for those who were in the best position to know

it.

ARTICLE VIII.

National Wars.

National wars, to which we have referred in speaking of those

of invasion, are the most formidable of all. This name can only

be applied to such as are waged against a united people, or a

great majority of them, filled with a noble ardor and determined

to sustain their independence: then every step is disputed, the

army holds only its camp-ground, its supplies can only be

obtained at the point of the sword, and its convoys are

everywhere threatened or captured.

The spectacle of a spontaneous uprising of a nation is rarely

seen; and, though there be in it something grand and noble which

commands our admiration, the consequences are so terrible that,

for the sake of humanity, we ought to hope never to see it. This

uprising must not be confounded with a national defense in

accordance with the institutions of the state and directed by the

government.

This uprising may be produced by the most opposite causes. The

serfs may rise in a body at the call of the government, and their

masters, affected by a noble love of their sovereign and country,

may set them the example and take the command of them; and,

similarly, a fanatical people may arm under the appeal of its

priests; or a people enthusiastic [Pg

30]in its political

opinions, or animated by a sacred love of its institutions, may

rush to meet the enemy in defense of all it holds most dear.

The control of the sea is of much importance in the results of

a national invasion. If the people possess a long stretch of

coast, and are masters of the sea or in alliance with a power

which controls it, their power of resistance is quintupled, not

only on account of the facility of feeding the insurrection and

of alarming the enemy on all the points he may occupy, but still

more by the difficulties which will be thrown in the way of his

procuring supplies by the sea.

The nature of the country may be such as to contribute to the

facility of a national defense. In mountainous countries the

people are always most formidable; next to these are countries

covered with extensive forests.

The resistance of the Swiss to Austria and to the Duke of

Burgundy, that of the Catalans in 1712 and in 1809, the

difficulties encountered by the Russians in the subjugation of

the tribes of the Caucasus, and, finally, the reiterated efforts

of the Tyrolese, clearly demonstrate that the inhabitants of

mountainous regions have always resisted for a longer time than

those of the plains,—which is due as much to the difference

in character and customs as to the difference in the natural

features of the countries.

Defiles and large forests, as well as rocky regions, favor

this kind of defense; and the Bocage of La Vendée, so

justly celebrated, proves that any country, even if it be only

traversed by large hedges and ditches or canals, admits of a

formidable defense.

The difficulties in the path of an army in wars of opinions,

as well as in national wars, are very great, and render the

mission of the general conducting them very difficult. The events

just mentioned, the contest of the Netherlands with Philip II.

and that of the Americans with the English, furnish evident

proofs of this; but the much more extraordinary struggle of La

Vendée with the victorious Republic, those of Spain,

Portugal, and the Tyrol against Napoleon, and, finally, those of

the Morea against the Turks, and of Na[Pg

31]varre against the

armies of Queen Christina, are still more striking

illustrations.

The difficulties are particularly great when the people are

supported by a considerable nucleus of disciplined troops. The

invader has only an army: his adversaries have an army, and a

people wholly or almost wholly in arms, and making means of

resistance out of every thing, each individual of whom conspires

against the common enemy; even the non-combatants have an

interest in his ruin and accelerate it by every means in their

power. He holds scarcely any ground but that upon which he

encamps; outside the limits of his camp every thing is hostile

and multiplies a thousandfold the difficulties he meets at every

step.

These obstacles become almost insurmountable when the country

is difficult. Each armed inhabitant knows the smallest paths and

their connections; he finds everywhere a relative or friend who

aids him; the commanders also know the country, and, learning

immediately the slightest movement on the part of the invader,

can adopt the best measures to defeat his projects; while the

latter, without information of their movements, and not in a

condition to send out detachments to gain it, having no resource

but in his bayonets, and certain safety only in the concentration

of his columns, is like a blind man: his combinations are

failures; and when, after the most carefully-concerted movements

and the most rapid and fatiguing marches, he thinks he is about

to accomplish his aim and deal a terrible blow, he finds no signs

of the enemy but his camp-fires: so that while, like Don Quixote,

he is attacking windmills, his adversary is on his line of

communications, destroys the detachments left to guard it,

surprises his convoys, his depots, and carries on a war so

disastrous for the invader that he must inevitably yield after a

time.

In Spain I was a witness of two terrible examples of this

kind. When Ney's corps replaced Soult's at Corunna, I had camped

the companies of the artillery-train between Betanzos and

Corunna, in the midst of four brigades distant from the camp from

two to three leagues, and no Spanish forces had been seen within

fifty miles; Soult still occupied Santiago [Pg 32]de

Compostela, the division Maurice-Mathieu was at Ferrol and Lugo,

Marchand's at Corunna and Betanzos: nevertheless, one fine night

the companies of the train—men and

horses—disappeared, and we were never able to discover what

became of them: a solitary wounded corporal escaped to report

that the peasants, led by their monks and priests, had thus made

away with them. Four months afterward, Ney with a single division

marched to conquer the Asturias, descending the valley of the

Navia, while Kellermann debouched from Leon by the Oviedo road. A

part of the corps of La Romana which was guarding the Asturias

marched behind the very heights which inclose the valley of the

Navia, at most but a league from our columns, without the marshal

knowing a word of it: when he was entering Gijon, the army of La

Romana attacked the center of the regiments of the division

Marchand, which, being scattered to guard Galicia, barely

escaped, and that only by the prompt return of the marshal to

Lugo. This war presented a thousand incidents as striking as

this. All the gold of Mexico could not have procured reliable

information for the French; what was given was but a lure to make

them fall more readily into snares.

No army, however disciplined, can contend successfully against

such a system applied to a great nation, unless it be strong

enough to hold all the essential points of the country, cover its

communications, and at the same time furnish an active force

sufficient to beat the enemy wherever he may present himself. If

this enemy has a regular army of respectable size to be a nucleus

around which to rally the people, what force will be sufficient

to be superior everywhere, and to assure the safety of the long

lines of communication against numerous bodies?

The Peninsular War should be carefully studied, to learn all

the obstacles which a general and his brave troops may encounter

in the occupation or conquest of a country whose people are all

in arms. What efforts of patience, courage, and resignation did

it not cost the troops of Napoleon, Massena, Soult, Ney, and

Suchet to sustain themselves for six years against three or four

hundred thousand armed Span[Pg

33]iards and Portuguese

supported by the regular armies of Wellington, Beresford, Blake,

La Romana, Cuesta, Castaños, Reding, and Ballasteros!

If success be possible in such a war, the following general

course will be most likely to insure it,—viz.: make a

display of a mass of troops proportioned to the obstacles and

resistance likely to be encountered, calm the popular passions in

every possible way, exhaust them by time and patience, display

courtesy, gentleness, and severity united, and, particularly,

deal justly. The examples of Henry IV. in the wars of the League,

of Marshal Berwick in Catalonia, of Suchet in Aragon and

Valencia, of Hoche in La Vendée, are models of their kind,

which may be employed according to circumstances with equal

success. The admirable order and discipline of the armies of

Diebitsch and Paskevitch in the late war were also models, and

were not a little conducive to the success of their

enterprises.

The immense obstacles encountered by an invading force in

these wars have led some speculative persons to hope that there

should never be any other kind, since then wars would become more

rare, and, conquest being also more difficult, would be less a

temptation to ambitious leaders. This reasoning is rather

plausible than solid; for, to admit all its consequences, it

would be necessary always to be able to induce the people to take

up arms, and it would also be necessary for us to be convinced

that there would be in the future no wars but those of conquest,

and that all legitimate though secondary wars, which are only to

maintain the political equilibrium or defend the public

interests, should never occur again: otherwise, how could it be

known when and how to excite the people to a national war? For

example, if one hundred thousand Germans crossed the Rhine and

entered France, originally with the intention of preventing the

conquest of Belgium by France, and without any other ambitious

project, would it be a case where the whole population—men,

women, and children—of Alsace, Lorraine, Champagne, and

Burgundy, should rush to arms? to make a Saragossa of every

walled town, to bring about, by way of reprisals, murder,

[Pg 34]pillage, and incendiarism throughout the country?

If all this be not done, and the Germans, in consequence of some

success, should occupy these provinces, who can say that they

might not afterward seek to appropriate a part of them, even

though at first they had never contemplated it? The difficulty of

answering these two questions would seem to argue in favor of

national wars. But is there no means of repelling such an

invasion without bringing about an uprising of the whole

population and a war of extermination? Is there no mean between

these contests between the people and the old regular method of

war between permanent armies? Will it not be sufficient, for the

efficient defense of the country, to organize a militia, or

landwehr, which, uniformed and called by their governments into

service, would regulate the part the people should take in the

war, and place just limits to its barbarities?

I answer in the affirmative; and, applying this mixed system

to the cases stated above, I will guarantee that fifty thousand

regular French troops, supported by the National Guards of the

East, would get the better of this German army which had crossed

the Vosges; for, reduced to fifty thousand men by many

detachments, upon nearing the Meuse or arriving in Argonne it

would have one hundred thousand men on its hands. To attain this

mean, we have laid it down as a necessity that good national

reserves be prepared for the army; which will be less expensive

in peace and will insure the defense of the country in war. This

system was used by France in 1792, imitated by Austria in 1809,

and by the whole of Germany in 1813.

I sum up this discussion by asserting that, without being a

utopian philanthropist, or a condottieri, a person may desire

that wars of extermination may be banished from the code of

nations, and that the defenses of nations by disciplined militia,

with the aid of good political alliances, may be sufficient to

insure their independence.

As a soldier, preferring loyal and chivalrous warfare to

organized assassination, if it be necessary to make a choice, I

acknowledge that my prejudices are in favor of the good

[Pg 35]old times when the French and English Guards

courteously invited each other to fire first,—as at

Fontenoy,—preferring them to the frightful epoch when

priests, women, and children throughout Spain plotted the murder

of isolated soldiers.

ARTICLE IX.

Civil Wars, and Wars of Religion.

Intestine wars, when not connected with a foreign quarrel, are

generally the result of a conflict of opinions, of political or

religious sectarianism. In the Middle Ages they were more

frequently the collisions of feudal parties. Religious wars are

above all the most deplorable.

We can understand how a government may find it necessary to

use force against its own subjects in order to crush out factions

which would weaken the authority of the throne and the national

strength; but that it should murder its citizens to compel them

to say their prayers in French or Latin, or to recognize the

supremacy of a foreign pontiff, is difficult of conception. Never

was a king more to be pitied than Louis XIV., who persecuted a

million of industrious Protestants, who had put upon the throne

his own Protestant ancestor. Wars of fanaticism are horrible when

mingled with exterior wars, and they are also frightful when they

are family quarrels. The history of France in the times of the

League should be an eternal lesson for nations and kings. It is

difficult to believe that a people so noble and chivalrous in the

time of Francis I. should in twenty years have fallen into so

deplorable a state of brutality.

To give maxims in such wars would be absurd. There is one rule

upon which all thoughtful men will be agreed: that is, to unite

the two parties or sects to drive the foreigners from the soil,

and afterward to reconcile by treaty the conflicting claims or

rights. Indeed, the intervention of a third power in a religious

dispute can only be with ambitious views.

Governments may in good faith intervene to prevent the

spreading of a political disease whose principles threaten

[Pg 36]social order; and, although these fears are

generally exaggerated and are often mere pretexts, it is possible

that a state may believe its own institutions menaced. But in

religious disputes this is never the case; and Philip II. could

have had no other object in interfering in the affairs of the

League than to subject France to his influence, or to dismember

it.

ARTICLE X.

Double Wars, and the Danger of Undertaking Two Wars at

Once.

The celebrated maxim of the Romans, not to undertake two great

wars at the same time, is so well known and so well appreciated

as to spare the necessity of demonstrating its wisdom.

A government maybe compelled to maintain a war against two

neighboring states; but it will be extremely unfortunate if it

does not find an ally to come to its aid, with a view to its own

safety and the maintenance of the political equilibrium. It will

seldom be the case that the nations allied against it will have

the same interest in the war and will enter into it with all

their resources; and, if one is only an auxiliary, it will be an

ordinary war.

Louis XIV., Frederick the Great, the Emperor Alexander, and

Napoleon, sustained gigantic struggles against united Europe.

When such contests arise from voluntary aggressions, they are

proof of a capital error on the part of the state which invites

them; but if they arise from imperious and inevitable

circumstances they must be met by seeking alliances, or by

opposing such means of resistance as shall establish something

like equality between the strength of the parties.

The great coalition against Louis XIV., nominally arising from

his designs on Spain, had its real origin in previous aggressions

which had alarmed his neighbors. To the combined forces of Europe

he could only oppose the faithful alliance of the Elector of

Bavaria, and the more equivocal one of the Duke of Savoy, who,

indeed, was not slow in [Pg

37]adding to the number

of his enemies. Frederick, with only the aid of the subsidies of

England, and fifty thousand auxiliaries from six different

states, sustained a war against the three most powerful

monarchies of Europe: the division and folly of his opponents

were his best friends.

Both these wars, as well as that sustained by Alexander in

1812, it was almost impossible to avoid.

France had the whole of Europe on its hands in 1793, in

consequence of the extravagant provocations of the Jacobins, and

the Utopian ideas of the Girondists, who boasted that with the

support of the English fleets they would defy all the kings in

the world. The result of these absurd calculations was a

frightful upheaval of Europe, from which France miraculously

escaped.

Napoleon is, to a certain degree, the only modern sovereign

who has voluntarily at the same time undertaken two, and even

three, formidable wars,—with Spain, with England, and with

Russia; but in the last case he expected the aid of Austria and

Prussia, to say nothing of that of Turkey and Sweden, upon which

he counted with too much certainty; so that the enterprise was

not so adventurous on his part as has been generally

supposed.

It will be observed that there is a great distinction between

a war made against a single state which is aided by a third

acting as an auxiliary, and two wars conducted at the same time

against two powerful nations in opposite quarters, who employ all

their forces and resources. For instance, the double contest of

Napoleon in 1809 against Austria and Spain aided by England was a

very different affair from a contest with Austria assisted by an

auxiliary force of a given strength. These latter contests belong

to ordinary wars.

It follows, then, in general, that double wars should be

avoided if possible, and, if cause of war be given by two states,

it is more prudent to dissimulate or neglect the wrongs suffered

from one of them, until a proper opportunity for redressing them

shall arrive. The rule, however, is not without exception: the

respective forces, the localities, the possibility [Pg 38]of

finding allies to restore, in a measure, equality of strength

between the parties, are circumstances which will influence a

government so threatened. We now have fulfilled our task, in

noting both the danger and the means of remedying it.

CHAPTER II.

MILITARY POLICY.

We have already explained what we understand by this title. It

embraces the moral combinations relating to the operations of

armies. If the political considerations which we have just

discussed be also moral, there are others which influence, in a

certain degree, the conduct of a war, which belong neither to

diplomacy, strategy, nor tactics. We include these under the head

of Military Policy.

Military policy may be said to embrace all the combinations of

any projected war, except those relating to the diplomatic art

and strategy; and, as their number is considerable, a separate

article cannot be assigned to each without enlarging too much the

limits of this work, and without deviating from my

intention,—which is, not to give a treatise on theses

subjects, but to point out their relations to military

operations.

Indeed, in this class we may place the passions of the nation

to be fought, their military system, their immediate means and

their reserves, their financial resources, the attachment they

bear to their government or their institutions, the character of

the executive, the characters and military abilities of the

commanders of their armies, the influence of cabinet councils or

councils of war at the capital upon their operations, the system

of war in favor with their staff, the established force of the

state and its armament, the military geography and statistics of

the state which is to be invaded, and, finally, the resources and

obstacles of every kind likely [Pg

39]to be met with, all

of which are included neither in diplomacy nor in strategy.

There are no fixed rules on such subjects, except that the

government should neglect nothing in obtaining a knowledge of

these details, and that it is indispensable to take them into

consideration in the arrangement of all plans. We propose to

sketch the principal points which ought to guide in this sort of

combinations.

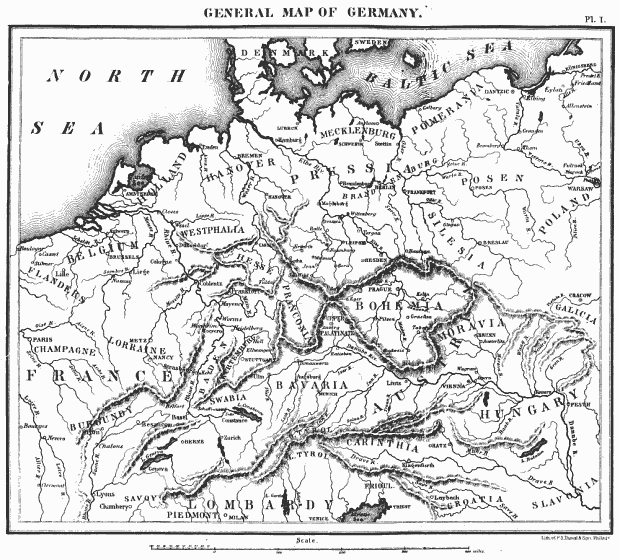

ARTICLE XI.

Military Statistics and Geography.

By the first of these sciences we understand the most thorough

knowledge possible of the elements of power and military

resources of the enemy with whom we are called upon to contend;

the second consists in the topographical and strategic

description of the theater of war, with all the obstacles,

natural or artificial, to be encountered, and the examination of

the permanent decisive points which may be presented in the whole

extent of the frontier or throughout the extent of the country.

Besides the minister of war, the commanding general and his chief

of staff should be afforded this information, under the penalty

of cruel miscalculations in their plans, as happens frequently in

our day, despite the great strides civilized nations have taken

in statistical, diplomatic, geographical, and topographical

sciences. I will cite two examples of which I was cognizant. In

1796, Moreau's army, entering the Black Forest, expected to find

terrible mountains, frightful defiles and forests, and was

greatly surprised to discover, after climbing the declivities of

the plateau that slope to the Rhine, that these, with their

spurs, were the only mountains, and that the country, from the

sources of the Danube to Donauwerth, was a rich and level

plain.

The second example was in 1813. Napoleon and his whole army

supposed the interior of Bohemia to be very

mountainous,—whereas there is no district in Europe more

level, after the girdle of mountains surrounding it has been

crossed, which may be done in a single march.

[Pg 40]All European officers held the same erroneous

opinions in reference to the Balkan and the Turkish force in the

interior. It seemed that it was given out at Constantinople that

this province was an almost impregnable barrier and the palladium

of the empire,—an error which I, having lived in the Alps,

did not entertain. Other prejudices, not less deeply rooted, have

led to the belief that a people all the individuals of which are

constantly armed would constitute a formidable militia and would

defend themselves to the last extremity. Experience has proved

that the old regulations which placed the elite of the

Janissaries in the frontier-cities of the Danube made the

population of those cities more warlike than the inhabitants of

the interior. In fact, the projects of reform of the Sultan

Mahmoud required the overthrow of the old system, and there was

no time to replace it by the new: so that the empire was

defenseless. Experience has constantly proved that a mere

multitude of brave men armed to the teeth make neither a good

army nor a national defense.

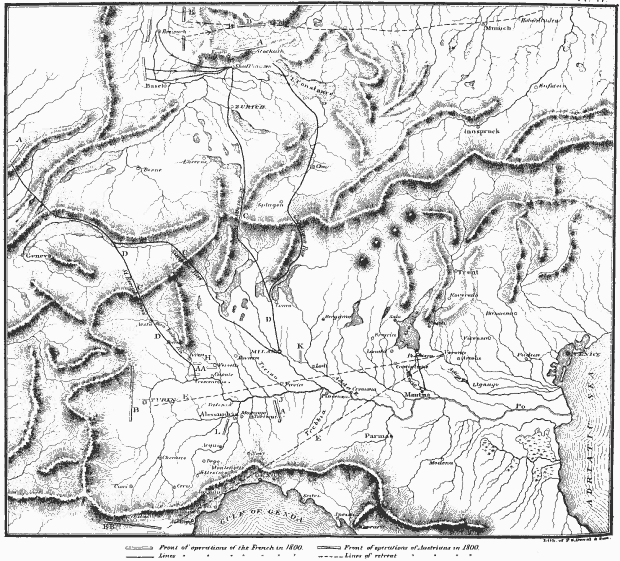

Let us return to the necessity of knowing well the military

geography and statistics of an empire. These sciences are not set

forth in treatises, and are yet to be developed. Lloyd, who wrote

an essay upon them, in describing the frontiers of the great

states of Europe, was not fortunate in his maxims and

predictions. He saw obstacles everywhere; he represents as

impregnable the Austrian frontier on the Inn, between the Tyrol

and Passau, where Napoleon and Moreau maneuvered and triumphed

with armies of one hundred and fifty thousand men in 1800, 1805,

and 1809.

But, if these sciences are not publicly taught, the archives

of the European staff must necessarily possess many documents

valuable for instruction in them,—at least for the special

staff school. Awaiting the time when some studious officer,

profiting by those published and unpublished documents, shall

present Europe with a good military and strategic geography, we

may, thanks to the immense progress of topography of late years,

partially supply the want of it by the excellent charts published

in all European countries within the last twenty years. At the

beginning of the French Revolution topo[Pg

41]graphy was in its

infancy: excepting the semi-topographical map of Cassini, the

works of Bakenberg alone merited the name. The Austrian and

Prussian staff schools, however, were good, and have since borne

fruit. The charts published recently at Vienna, at Berlin,

Munich, Stuttgart, and Paris, as well as those of the institute

of Herder at Fribourg, promise to future generals immense

resources unknown to their predecessors.

Military statistics is not much better known than geography.

We have but vague and superficial statements, from which the

strength of armies and navies is conjectured, and also the

revenue supposed to be possessed by a state,—which is far

from being the knowledge necessary to plan operations. Our object

here is not to discuss thoroughly these important subjects, but

to indicate them, as facilitating success in military

enterprises.

ARTICLE XII.

Other Causes which exercise an Influence upon the Success of

a War.

As the excited passions of a people are of themselves always a

powerful enemy, both the general and his government should use

their best efforts to allay them. We have nothing to add to what

has been said on this point under the head of national wars.

On the other hand, the general should do every thing to

electrify his own soldiers, and to impart to them the same

enthusiasm which he endeavors to repress in his adversaries. All

armies are alike susceptible of this spirit: the springs of

action and means, only, vary with the national character.

Military eloquence is one means, and has been the subject of many

a treatise. The proclamations of Napoleon and of Paskevitch, the

addresses of the ancients to their soldiers, and those of

Suwaroff to men of still greater simplicity, are models of their

different kinds. The eloquence of the Spanish Juntas, and the

miracles of the Madonna del Pilar, led to the same results by

very different means. In general, a cherished cause, and a

general who inspires confidence by previous success, are powerful

means of electrifying an army and [Pg

42]conducing to

victory. Some dispute the advantages of this enthusiasm, and

prefer imperturbable coolness in battle. Both have unmistakable

advantages and disadvantages. Enthusiasm impels to the

performance of great actions: the difficulty is in maintaining it

constantly; and, when discouragement succeeds it, disorder easily

results.

The greater or less activity and boldness of the commanders of

the armies are elements of success or failure, which cannot be

submitted to rules. A cabinet and a commander ought to consider

the intrinsic value of their troops, and that resulting from

their organization as compared with that of the enemy. A Russian

general, commanding the most solidly organized troops in Europe,

need not fear to undertake any thing against undisciplined and

unorganized troops in an open country, however brave may be its

individuals.[1] Concert in action makes

strength; order produces this concert, and discipline insures

order; and without discipline and order no success is possible.

The Russian general would not be so bold before European troops

having the same instruction and nearly the same discipline as his

own. Finally, a general may attempt with a Mack as his antagonist

what it would be madness to do with a Napoleon.

The action of a cabinet in reference to the control of armies

influences the boldness of their operations. A general whose

genius and hands are tied by an Aulic council five hundred miles

distant cannot be a match for one who has liberty of action,

other things being equal.

As to superiority in skill, it is one of the most certain

pledges of victory, all other things being equal. It is true that

great generals have often been beaten by inferior ones; but an

exception does not make a rule. An order misunderstood, a

fortuitous event, may throw into the hands of the enemy all the

chances of success which a skillful general had prepared for

himself by his maneuvers. But these are risks which cannot be

foreseen nor avoided. Would it be fair on [Pg 43]that

account to deny the influence of science and principles in

ordinary affairs? This risk even proves the triumph of the

principles, for it happens that they are applied accidentally by

the army against which it was intended to apply them, and are the

cause of its success. But, in admitting this truth, it may be

said that it is an argument against science; this objection is

not well founded, for a general's science consists in providing

for his side all the chances possible to be foreseen, and of

course cannot extend to the caprices of destiny. Even if the

number of battles gained by skillful maneuvers did not exceed the

number due to accident, it would not invalidate my assertion.

If the skill of a general is one of the surest elements of

victory, it will readily be seen that the judicious selection of

generals is one of the most delicate points in the science of

government and one of the most essential parts of the military

policy of a state. Unfortunately, this choice is influenced by so

many petty passions, that chance, rank, age, favor, party spirit,

jealousy, will have as much to do with it as the public interest

and justice. This subject is so important that we will devote to

it a separate article.

FOOTNOTES:

[1]

Irregular troops supported by disciplined troops may be of the

greatest value, in destroying convoys, intercepting

communication, &c., and may—as in the case of the

French in 1812—make a retreat very disastrous.

ARTICLE XIII.

Military Institutions.

One of the most important points of the military policy of a

state is the nature of its military institutions. A good army

commanded by a general of ordinary capacity may accomplish great

feats; a bad army with a good general may do equally well; but an

army will certainly do a great deal more if its own superiority

and that of the general be combined.

Twelve essential conditions concur in making a perfect

army:—

1. To have a good recruiting-system;

2. A good organization;

8. A well-organized system of national reserves;

4. Good instruction of officers and men in drill and internal

duties as well as those of a campaign;

5. A strict but not humiliating discipline, and a spirit of

[Pg 44]subordination and punctuality, based on conviction

rather than on the formalities of the service;

6. A well-digested system of rewards, suitable to excite

emulation;

7. The special arms of engineering and artillery to be well

instructed;

8. An armament superior, if possible, to that of the enemy,

both as to defensive and offensive arms;

9. A general staff capable of applying these elements, and

having an organization calculated to advance the theoretical and

practical education of its officers;

10. A good system for the commissariat, hospitals, and of

general administration;

11. A good system of assignment to command, and of directing

the principal operations of war;

12. Exciting and keeping alive the military spirit of the

people.

To these conditions might be added a good system of clothing

and equipment; for, if this be of less direct importance on the

field of battle, it nevertheless has a bearing upon the

preservation of the troops; and it is always a great object to

economize the lives and health of veterans.

None of the above twelve conditions can be neglected without

grave inconvenience. A fine army, well drilled and disciplined,

but without national reserves, and unskillfully led, suffered

Prussia to fall in fifteen days under the attacks of Napoleon. On

the other hand, it has often been seen of how much advantage it

is for a state to have a good army. It was the care and skill of

Philip and Alexander in forming and instructing their phalanxes

and rendering them easy to move, and capable of the most rapid

maneuvers, which enabled the Macedonians to subjugate India and

Persia with a handful of choice troops. It was the excessive love

of his father for soldiers which procured for Frederick the Great

an army capable of executing his great enterprises.

A government which neglects its army under any pretext

whatever is thus culpable in the eyes of posterity, since it

prepares humiliation for its standards and its country, instead

[Pg 45]of by a different course preparing for it success.

We are far from saying that a government should sacrifice every

thing to the army, for this would be absurd; but it ought to make

the army the object of its constant care; and if the prince has

not a military education it will be very difficult for him to

fulfill his duty in this respect. In this case—which is,

unfortunately, of too frequent occurrence—the defect must

be supplied by wise institutions, at the head of which are to be

placed a good system of the general staff, a good system of

recruiting, and a good system of national reserves.

There are, indeed, forms of government which do not always

allow the executive the power of adopting the best systems. If

the armies of the Roman and French republics, and those of Louis

XIV. and Frederick of Prussia, prove that a good military system

and a skillful direction of operations may be found in

governments the most opposite in principle, it cannot be doubted

that, in the present state of the world, the form of government

exercises a great influence in the development of the military

strength of a nation and the value of its troops.

When the control of the public funds is in the hands of those

affected by local interest or party spirit, they may be so

over-scrupulous and penurious as to take all power to carry on

the war from the executive, whom very many people seem to regard

as a public enemy rather than as a chief devoted to all the

national interests.

The abuse of badly-understood public liberties may also

contribute to this deplorable result. Then it will be impossible

for the most far-sighted administration to prepare in advance for

a great war, whether it be demanded by the most important

interests of the country at some future time, or whether it be

immediate and necessary to resist sudden aggressions.

In the futile hope of rendering themselves popular, may not

the members of an elective legislature, the majority of whom

cannot be Richelieus, Pitts, or Louvois, in a misconceived spirit

of economy, allow the institutions necessary for a large,

well-appointed, and disciplined army to fall into decay?

[Pg 46]Deceived by the seductive fallacies of an

exaggerated philanthropy, may they not end in convincing

themselves and their constituents that the pleasures of peace are

always preferable to the more statesmanlike preparations for

war?

I am far from advising that states should always have the hand

upon the sword and always be established on a war-footing: such a

condition of things would be a scourge for the human race, and

would not be possible, except under conditions not existing in

all countries. I simply mean that civilized governments ought

always to be ready to carry on a war in a short time,—that

they should never be found unprepared. And the wisdom of their

institutions may do as much in this work of preparation as

foresight in their administration and the perfection of their

system of military policy.

If, in ordinary times, under the rule of constitutional forms,

governments subjected to all the changes of an elective

legislature are less suitable than others for the creation or

preparation of a formidable military power, nevertheless, in

great crises these deliberative bodies have sometimes attained

very different results, and have concurred in developing to the

full extent the national strength. Still, the small number of

such instances in history makes rather a list of exceptional

cases, in which a tumultuous and violent assembly, placed under

the necessity of conquering or perishing, has profited by the

extraordinary enthusiasm of the nation to save the country and

themselves at the same time by resorting to the most terrible

measures and by calling to its aid an unlimited dictatorial

power, which overthrew both liberty and law under the pretext of

defending them. Here it is the dictatorship, or the absolute and

monstrous usurpation of power, rather than the form of the

deliberative assembly, which is the true cause of the display of

energy. What happened in the Convention after the fall of

Robespierre and the terrible Committee of Public Safety proves

this, as well as the Chambers of 1815. Now, if the dictatorial

power, placed in the hands of a few, has always been a plank of

safety in great crises, it seems natural to draw the conclusion

that countries controlled by elective assemblies must be

politically and militarily weaker than [Pg

47]pure monarchies,

although in other respects they present decided advantages.

It is particularly necessary to watch over the preservation of

armies in the interval of a long peace, for then they are most

likely to degenerate. It is important to foster the military

spirit in the armies, and to exercise them in great maneuvers,

which, though but faintly resembling those of actual war, still

are of decided advantage in preparing them for war. It is not

less important to prevent them from becoming effeminate, which

may be done by employing them in labors useful for the defense of

the country.

The isolation in garrisons of troops by regiments is one of

the worst possible systems, and the Russian and Prussian system

of divisions and permanent corps d'armée seems to be much

preferable. In general terms, the Russian army now may be

presented as a model in many respects; and if in many points its

customs would be useless and impracticable elsewhere, it must be

admitted that many good institutions might well be copied from

it.

As to rewards and promotion, it is essential to respect long

service, and at the same time to open a way for merit.

Three-fourths of the promotions in each grade should be made

according to the roster, and the remaining fourth reserved for

those distinguished for merit and zeal. On the contrary, in time

of war the regular order of promotion should be suspended, or at

least reduced to a third of the promotions, leaving the other

two-thirds for brilliant conduct and marked services.

The superiority of armament may increase the chances of

success in war: it does not, of itself, gain battles, but it is a

great element of success. Every one can recall how nearly fatal

to the French at Bylau and Marengo was their great inferiority in