|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER VII. THE ANDEAN SOUTH

I The Empire of the Incas

II The Yunca Pantheons

III The Myths of the Chincha

IV Viracocha and Tonapa

V The Children of the Sun

VI Legends of the Incas

I. THE EMPIRE OF THE INCAS

1 IN this land of Peru," wrote Cieza de Leon, 2 "are three desert ranges where men can in no wise exist. One of these comprises the montana (forests) of the Andes, full of dense wilder- nesses where men cannot live, nor ever have lived. The second is the mountainous region, extending the whole length of the Cordillera of the Andes, which is intensely cold, and its summits are covered with eternal snow, so that in no way can people live in this region owing to the snow and the cold, and also because there are no provisions, all things being destroyed by the snow and the wind, which never ceases to blow. The third range comprises the sandy deserts from Tumbez to the other side of Tarapaca, in which there is nothing to be seen but sand-hills and the fierce sun which dries them up, without water, nor herb, nor tree, nor created thing, except birds which, by the gift of their wings, wander wherever they list. This kingdom, being so vast, has great deserts for the reasons I have now given.

"The inhabited region is after this fashion. In parts of the mountains of the Andes are ravines and dales, which open out into deep valleys of such width as often to form great plains between the mountains; and although the snow falls, it all remains on the higher part. As these valleys are closed in, they are not molested by the winds, nor does the snow reach them, and the land is so fruitful that all things which are sown yield abundantly; and there are trees and many birds and animals. The land being so fertile, is well peopled by the natives. They make their villages with rows of stones roofed with straw, and live healthily and in comfort. Thus the mountains of the Andes form these dales and ravines in which there are populous villages, and rivers of excellent water flow near them, some of the rivers send their waters to the South Sea, entering by the sandy deserts which I have mentioned, and the humidity of their water gives rise to very beautiful valleys with great rows of trees. The valleys are two or three leagues broad, and great quantities of algoroba trees [Prosopis horrida] grow in them, which flourish even at great distances from any water. Wherever there are groves of trees the land is free from sand and very fertile and abundant. In ancient times these valleys were very populous, and still there are Indians in them, though not so many as in former days. As it never rains in these sandy deserts and valleys of Peru, they do not roof their houses as they do in the mountains, but build large houses of adobes [sun-dried bricks] with pleasant terraced roofs of matting to shade them from the sun, nor do the Spaniards use any other roofing than these reed mats. To prepare their fields for sowing, they lead channels from the rivers to irrigate the valleys, and the channels are made so well and with so much regularity that all the land is irrigated without any waste. This system of irrigation makes the valleys very green and cheerful, and they are full of fruit-trees both of Spain and of this country. At all times they raise good harvests of maize and wheat, and of everything that they sow. Thus, although I have described Peru as being formed of three desert ridges, yet from them, by the will of God, descend these valleys and rivers, without which no man could live. This is the cause why the natives were so easily conquered, for if they rebelled they would all perish of cold and hunger. Except the land which they inhabit, the whole country is full of snowy mountains, enormous and very terrible."

Cieza de Leon's description brings vividly before the imagination the physical surroundings which made possible the evolution and the long history of the greatest of native American empires. Divided from one another by towering mountains and inhospitable deserts, the tribes and clans that filtered into this region at some remote period were compelled to develop in relative isolation; while, further, the conditions of existence were such that the inhabitants could not be nomadic huntsmen, nor even fishermen. Along the shores are vestiges of ancient shell-heaps, indicative of utterly primitive fisher-folk, and the sea always remained an important source of food for the coastal peoples ; yet even here, as Cieza de Leon indicates, the growth of population was dependent upon an intensive cultivation of the narrow river-valleys rather than upon the conquest of new territories. Thus, the whole environment of life in Peru, montane and littoral, is framed by the fact of more or less constricted and protected valley centres, immensely productive in response to toil, but yielding no idyllic fruits to unlaborious ease. If the peoples who inhabited these valleys were not agriculturists when they entered them, they were compelled to become such in order that they might live and increase; and while the stupendous thrift of the aborigines, as evidenced by their stone-terraced gardens, their elaborate aqueducts, and their wonderful roads, still excites the astonishment of beholders, it is none the less intelligible as the inevitable consequence of prolonged human habitation. It is certain that the Peruvian peoples were the most accomplished of all Americans in the working of the soil; and it is possible that they were the originators of agriculture in America, for it was from Peru, apparently, that the growing of maize spread throughout wide regions of South America, Peru that developed the potato as a food-crop, and in Peru that the cultivation of cotton and various fruits and vegetables added greatest variety to the native farming.

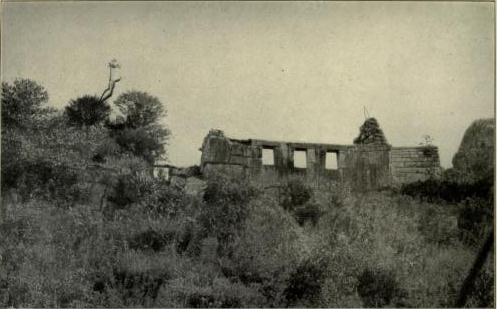

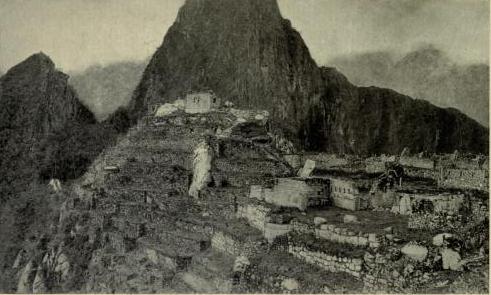

PLATE XXX: Machu Picchu, in the valley of the Urubamba, north of Cuzco. These ruins of an ancient Inca city were discovered by Hiram Bingham, of the Yale University and National Geographical Society expedition, in 1911, and are by him identified with the "Tampu-Tocco" of Inca tradition. From photograph, courtesy of Hiram Bingham, Director of the Yale Peruvian Expedition.

Peru, likewise, was the only American centre in which there was a domestic animal more important than the dog; and the antiquity of the taming of the llama and alpaca useful not only for food and wool, but also as beasts of burden is shown by the fact that these animals show marked differentiation from the wild guanaco from which they are derived. The development of domestic species of this animal and, even more, the development of maize from its ancestral grasses (if indeed this were Peruvian) 3 imply many centuries of settled and industrious life, a consideration which adds strongly to the archaeological and legendary indications of a civilization that must be reckoned in millennia.

The conditions which thus fostered local and intensive cultural evolutions were scarcely less favourable once the local valleys had reached a certain complexity to the formation of extensive empires. As Cieza de Leon remarks, conquest was easy where refuge was difficult; and the Inca conquerors themselves found that the most effective weapon they could employ against the coastal cities was mastery of their aqueducts. The town which lost control of its water, drawn from the hills, could only surrender; and thus, the segregated valleys fell an easy prey to a powerful and aggressive people, gifted with engineering skill, such as the Inca race; while the empire won was not difficult to hold. At the time of the Spanish conquest that empire was truly immense. Tahuantinsuyu ("the Four Quarters") was the native name, and "the Quartered City" (Cuzco), its capital, was regarded as the Navel of the World. The four quarters, or provinces, were oriented from Cuzco: the southerly was Collasuyu, stretching from the neighbourhood of Lake Titicaca southward; the eastern province was Antisuyu, extending down the slopes of the Andes into the regions of savagery; to the west lay Cuntisuyu, reaching to the coast and to the lands of the Yunca peoples; while to the north was Chinchasuyu, following the Andean valleys. Shortly before the Conquest the Inca dominion had been imposed upon the realm of the Scyris of Quito, so that the northern boundary lay beyond the equator; while the extreme southerly border had recently been extended over the Calchaqui tribes and down the coast to the edges of Araucania in the neighbourhood of latitude 35 south.

The imperial territories were naturally narrowed to the Andean region, for the tropical forests to the east offered no allurements to the mountain-loving race which, indeed, could endure only temporarily the heat of the western coast, so that Inca campaigners in this direction resorted to frequent reliefs lest their men be debilitated. On the other hand, the immense expanse north and south, notwithstanding the perfection of the roads and fortresses built by astute rulers to facilitate communication, caused a natural tension of the parts and a tendency to break at the appearance of even the least weakness at the centre. Such appears to have been the fatal defect underlying the conflict of Huascar, at Cuzco, with Atahualpa, whose initial strength lay in his possession of Quito, and whose career was brought to an untimely end by the advent of Pizarro. Despite the fact that Inca power had been clearly crescent within the generation, it is by no means certain that the political conditions which the Spaniards used to advantage might not, if left to themselves, have disrupted the great empire.

There is reason to think that such a rupture had occurred at least once before in the history of Andean civilization. The list of more than a hundred Peruvian kings given by the Licentiate Fernando Montesinos (writing about 1650) 4 was formerly viewed with much distrust, chiefly for the reason that the kings of the pre-Inca dynasties recorded by Montesinos are almost without exception unnamed by earlier and prime authorities on Peruvian history (including Garcilasso de la Vega and Cieza de Leon). Recent discoveries, however, both scholarly and archaeological, have brought a new plausibility to Montesinos's lists, and it appears probable that he derived them from the lost works of Bias Valera, one of the earliest men in the field, known to have had exceptional opportunities for a study of native lore; while at the same time the archaeological investigations of Max Uhle and the brilliant achievements of the expeditions headed by Hiram Bingham have given a new definiteness to knowledge of pre-Inca conditions.5

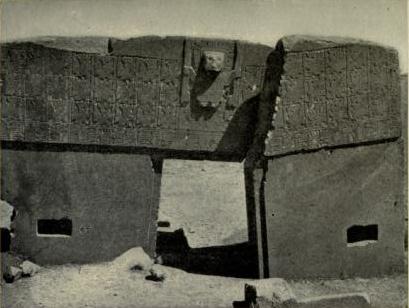

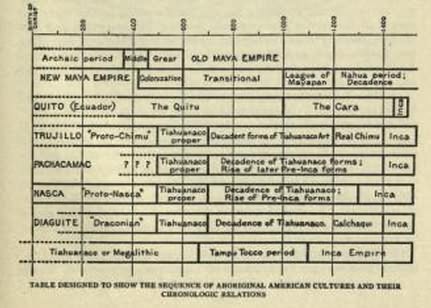

It has long been known that Inca civilization was only the last in a series of Peruvian culture periods. Back of it, in the highlands, lay the Megalithic Age, so called from the great size of the stone blocks in its cyclopean masonry, the earliest centre of this culture being supposed to have been about Lake Titicaca, and especially Tiahuanaco, at the south of the lake a site remarkable not only for the most extraordinary of all ancient American monuments, the monolithic gate and the surrounding precincts, but also for the importance ascribed to it in legend as a place of origin of nations. Other highland centres, however, hark back to the same period, and Cuzco itself, in old cyclopean walls, shows evidence of an age of Megalithic greatness upon which the later Inca civilization had supervened. Again, in the coastal region from lea to Truxillo the realms of the Yunca, according to the older chroniclers there were several successive culture periods; and though it is possible that traditions such as that of Naymlap (see Chapter VI, Section V) indicate a foreign origin for the Yunca peoples, in any case their differing environment would account for much. The peoples of the littoral could have no herds of llamas, since the animal was unable to live in that region; and hence they looked mainly to cotton for their fabrics, while the sea gave them fair compensation in the matter of food. In the lesser arts, especially in that of the potter, they surpassed the highlanders and, indeed, all other Americans; but their building material was adobe, and they have left no magnificent monuments, as have the stone-workers of the hills. Nevertheless at some remote, pre-Inca period the ideas of the coast and those of the highlands met and interchanged: the art of Tiahuanaco is reflected in motive at Truxillo, while the vases of Nasca repeat the bizarre decoration of the monolith of Chavin de Huantar. The hoary sanctity of the great temple of Pachacamac was such that its Inca conqueror adopted the god into his own pantheon; and it was just here, at the Yunca shrine of Pachacamac, that Uhle found evidence of a series of culture periods leading to a considerable antiquity. The indigenous coastal art had already passed its climax of expressive skill when the influence of Tiahuanaco appeared; but this influence lasted long enough to leave an enduring impress on the interregnum-like period which followed, awaiting, as it were, the return of the hills' influence, which came with the advent of the Inca. Such, in brief, is the restoration, and it seems to fit remarkably with Bingham's discoveries and with Montesinos's lists.

Of the one hundred and two kings in these lists, the last ten form the Inca dynasty (a group with respect to which Montesinos is in essential agreement with other chroniclers), whose beginning is placed 1100-1200 A. D.; back of these are the twenty-eight lords of Tampu-Tocco; and still earlier the sixty-four rulers of the ancient empire, forty-six of them forming the amauta (or priest-king) dynasty which followed after the primal line of eighteen Sons of the Gods. Were this scheme of regal succession followed out in extenso the beginnings of the Megalithic Empire of the highlands should fall near the beginning of the first millenium before Christ, and that of the Tampu Tocco dynasty in the early years of our Era. Archaeological and other considerations lead, however, to estimates somewhat more conservative, placing the culmination of the early empire in the first centuries of the Christian era, and the sojourn at Tampu Tocco from about 600 1 100 A. D. 6

The Inca dynasty, established at Cuzco toward 1200 A. D., was the creator of the great empire which the Spaniards found, and its record is the traditional history of Peru, recounted by Garcilasso and Cieza. According to the legend, the Inca tribes had come to Cuzco from a place called Tampu-Tocco, a city of refuge in an inaccessible valley, where for centuries their ancestors had lived in seclusion, the cause of the retirement being as follows : in past generations, it was said, the Amauta dynasty held sway over a great highland realm, extending from Tucuman in the south to Huanuco in the north, the empire having been formed perhaps by the earlier royal house, which was called Pirua, after the name of its first King. In the reign of the forty-sixth Amauta, there came an invasion of hordes from the south and east, preceded by comets, earthquakes, and dire divinations. The King Titu Yupanqui, borne on a golden litter, led his soldiers out to battle; he was slain by an arrow, and his discouraged followers retreated with his body. Cuzco fell, and after war came pestilence, leaving city and country uninhabitable, while the remnants of the Amauta people fled away to Tampu-Tocco, where they established themselves, leaving at Cuzco only a few priests who refused to abandon the shrine of the Sun. It was said that the art of writing was lost in this debacle, and that the later art of reckoning by quipus, or knotted and coloured cords, was invented at Tampu-Tocco. Here, in a city free from pests and unmoved by earthquakes, the Kings of Tampu-Tocco reigned in peace, going occasionally to Cuzco to worship at the ancient shrine, over which, with its neighborhood, some shadowy authority was preserved. Finally a woman, Siyu-Yacu, of noble birth and high ambition, caused the report to be spread that her son, Rocca, had been carried off to be instructed by the Sun himself, and a few days later the youth, appearing in a garment glittering with gold, told the people that corruption of the ancient religion had caused their fall, but that their lost glories should be restored to them under his leadership. Thus Rocca became the first of the Incas, Cuzco was restored as capital, and the new empire started on a career which was to exceed the old in grandeur.

With the removal to Cuzco, Tampu-Tocco became no more than a monumental shrine where priests and vestals preserved the rites of the old religion and watched over the caves made sacred by the bones of former monarchs. The native writer Salcamayhua, who, like Garcilasso, makes Manco Capac the founder of the Incas (Montesinos regards Manco Capac I as the first native-born king of the Pirua dynasty), tells how "at the place of his birth he ordered works to be executed, consisting of a masonry wall with three windows, which were emblems of the house of his fathers, whence he descended"; and the name Tampu-Tocco actually means "Tavern of the Windows," windows being an unusual feature of Peruvian architecture. As the event proves, the commemorative wall is still standing.

In 1911, Hiram Bingham, the leader of the expedition sent out by Yale University and the National Geographical Society, discovered in the wild valley of the Urubamba, north of Cuzco, the ruins of a mountain-seated city, one of the most wonderful, and (in its natural context) beautiful ruins in the world. Machu Picchu the place is called, and its discoverer identifies it with the Tampu-Tocco of Inca tradition. One of its most striking features is a wall with three great windows; it contains cave-made graves and temples; bones of the more recent dead indicate that those who last dwelt in it were priestesses and priests; and it gives evidence of long occupation. The more ancient stonework is the more beautiful in execution, seeming to hark back to the masterpieces of Megalithic civilization; the later portion is in Inca style. Especially interesting is the discovery of record stones, associated with the older period, indicating that an earlier method of chronology had been replaced in later times, for it is to the reign of the thirteenth King of Tampu-Tocco that the invention of quipus is ascribed. Ideally placed as a city of refuge in a remote canon, so that its very existence was unknown to the Spanish conquerors; seated on a granite hill unmoved by earthquakes; with its elaborate structures and complicated terraces indicating generations of residence, Machu Picchu represents the connecting link between the old and the new empires in Peru and gives a suddenly vivid plausibility to the traditions recorded by Montesinos.

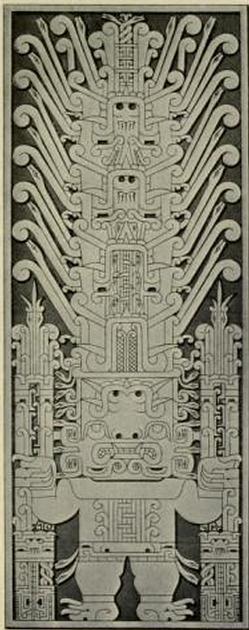

PLATE XXXI

Sculptured monolith from Chavin de Huantar, now in the Museum of Lima. The design appears to be a deity armed with thunderbolts or elaborate wands, with a monster head surmounted by an elaborate head-dress. If the figure be viewed reversed the head-dress will be seen to consist of a series of masks each pendent from the protruding tongue of the mask above, a motive frequent in Nasca pottery (cf. Plate XXXII). The figure strongly suggests the central image of the Tiahuanaco monolithic gateway, but it is to be observed that serpent heads, from the girdle, the rays of the head-dress, and in the caduceus-like termination of the headdress, take the place of the puma, fish and condor accessories of the Tiahuanaco monument. The relationship of this deity to those represented on Plates XXXII, XXXIII, XXXIV, XXXV, and XXXVII, is scarcely to be doubted. Markham, Incas of Peru, page 34.

Thus, in shadowy fashion, the cycles of Andean civilization are restored. There are two great regions, the highland and the littoral, Inca and Yunca, each with a long history. The primitive fisher-families of the coast gave way to a civilization which may have received its impetus, as traditions indicate, from tribes sailing southward in great balsas, at any rate it had developed, doubtless before the Christian era, important and characteristic culture centres Truxillo in the north, Nasca to the south and great shrines, Pachacamac and Rimac, venerable to the Incas; while long after its own acme, and long before the Inca conquest, the coastal civilization had had important commerce with the ancient culture of the highlands. The origin of the pre-Inca empire from the Megalithic culture of Tiahuanaco leads back toward the middle of the first millemum B. c., perhaps to dimly remote centuries. It passed its floruit, marked by the rise of Cuzco as a great capital, and then followed barbarian migrations and wars; the retirement of a defeated handful to Tampu-Tocco; a long period of decline; and finally, about the beginning of the thirteenth century, a renaissance of culture, marked by a religious reform amounting to a new dispensation and stamping the revived power as essentially ecclesiastical in its claims, for all Inca conquests were undertaken with a Crusader's plea for the expansion of the faith in the beneficent Sun and for the spread of knowledge of the Way of Life revealed through his children, the Inca.

It is impossible not to be struck with the resemblance between the development of this civilization and that of Europe during the same period. Cuzco and Rome rise to empire simultaneously; the ancient civilizations of Tiahuanaco, Nasca, and Truxillo, excelling the new power in art, but inferior in power of organization and engineering works, are the American equivalents of Greece and the Orient. Almost synchronously, Rome and Cuzco fall before barbarian invasions; and in each case centuries follow which can only be known as dark, during which the empire breaks in chaos. Finally, both civilizations rise, again during the same period, as leaders in a new movement in religion, animated by a crusading zeal and basing their authority upon divine will. It is true that Rome does not attain the material power that was restored to Cuzco, but Christendom, at least, does attain this power. Such is the picture, though it must be added that in the present state of knowledge it is plausible restoration only, not proven truth.

II. THE YUNCA PANTHEONS

It is not possible to reconstruct in any detail the religions and mythologies of the pre-Inca civilizations of the central Andes, but of the four culture centres which have been most studied some traits are decipherable. Two of these centres are montane, two coastal. Of the former, the Megalithic highland civilization, whose first home is supposed to have been the region of Lake Titicaca, is assuredly ancient; the civilization of the Calchaqui, to the south of this, was a late conquest of the Incas and was doubtless a contemporary of Inca culture. On the coast, the Yunca developed in two branches, both, apparently, as ancient as the Megalithic culture, and both, again, late conquests of the Incas. To the north, extending from Tumbez to Paramunca, with Chimu (Truxillo) as its capital, was the realm of the Grand Chimu a veritable empire, for it comprised some twenty coastal valleys while the twelve adjoining southern valleys, from Chancay to Nasca, were the seat of the Chincha Confederacy, a loose political organization with a characteristic culture of its own, though clearly akin to that of the Chimu region. All these centres having fallen under the sway of conquerors with a creed to impose (the Incas even erected a shrine to the Sun on the terraces of oracular Pachacamac), their religious traditions were waning in importance in the time of the conquistadores, who, unhappily, secured little of the lore that might have been salved in their own day. There are fragments for the Chimu region in Balboa and Calancha, for the Chincha in Arriaga and Avila; but in the main it is upon the monuments vases, burials, ruins of temples that, in any effort to define the beliefs of these departed peoples, we must depend for a supplementation of the meagre notices recorded in Inca tradition or preserved by the early chroniclers. 7

Fortunately these monuments permit of some interesting guesses which, surely, are no unjustified indulgence of human curiosity when the mute expression of dead souls is their matter; and in particular the wonderful drawings of the Truxillo and Nasca vases and the woven figures of their fabrics suggest analogical interpretation. Despite their family likeness, the styles of the two regions are distinct; and, as the investigations of Uhle show, they have undergone long and changing developments, with apogees well in the past. The zenith of Chimu art was marked by a variety and naturalism of design rivaled, if at all in America, only by the best Maya achievements; while Chincha expression realized its acme in polychrome designs truly marvellous in complexity of convention. That the art of both regions is profoundly mythological is obvious from the portrayals.

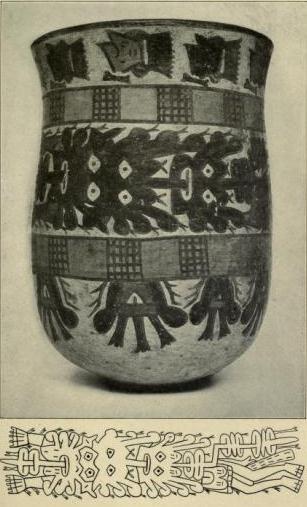

Striking features of this Yunca art are the monster-forms 8 - man-bird, man-beast, man-fish, man-reptile and, again, the multiplication of faces or masks, both of men and of animals. The repetition of the human countenance is especially frequent in the art of Nasca, where series of masks are often enchained in complex designs, one most grotesque form of this concatenation representing a series of masks issuing, as it were, from the successive mouths, and joined by the protruding tongues. Again, there are dragon-like or serpentine monsters having a head at each extremity, recalling not only the two-headed serpent of Aztec and Maya art, but also the Sisiutl of the North-West Coast of North America a region whose art, also, furnishes an impressive analogue, in complexity of convention, to that of the Yunca. Frequently, in Nasca art, the fundamental design is a man-headed bird, or fish, or serpent, whose body and accoutrements are complexly adorned with representations of the heads or forms of other animals the puma, for example, or even the mouse. Oftentimes heads, apparently decapitations, are borne in the hands of the central figure; and on one Truxillo vase there is a depiction 9 of what is surely a ceremonial dance in which the participants are masked and disguised as birds and animals; the remarkable Nasca robes in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (see Plates XXXI, XXXII, XXXIII, XXXIV) also suggest masked forms, the representations of the same personage varying in colour and in the arrangement of facial design.

The heads which are held in the hands and which adorn the costumes of these figures are regarded by some authorities as trophy heads, remotely related, perhaps, to those which are prepared as tokens of prowess by some of the Brazilian tribes; and, in fact, the discovery of the decapitated mummies of women and girls, buried in the guano deposits of the sacred islands of Guafiape and Macabi, points to a remote period when human sacrifices were made, perhaps to a marine power, and certainly connected with some superstition as to the head. Another suggestion, however, will account for a greater variety of the forms. The dances with animal masks irresistibly recall the ancestral and totemic masked dances of such peoples as the Pueblo Indians of North America and of the tribes of the North-West Coast; the figures of bird-men, fish-men, and snake-men, with their bodies ornamented with other animal figures, are again reminiscent of the totemic emblems of the far North-West; and surely no image is better adapted to suggest the descent of a series of generations from an ancestral hero than the sequence of tongue-joined masks figured on the Nasca vases, each generation receiving its name, as it were, from the mouth of the preceding. The recurrence of certain constant designs, both on vases and in fabrics, is at least analogous to the use of totemic signs on garments and utensils in the region of the North-West Coast.

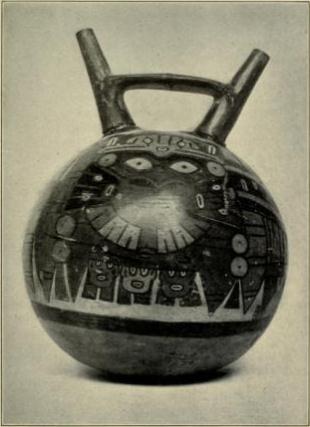

PLATE XXXII: Polychrome vase from the Nasca valley, showing the multi-headed deity represented also by Plate XXXI. The succession of masks connected by protruded tongues is a striking form of Nasca design. Examples are found elsewhere, even into Calchaqui territory. The vase here pictured is in the American Museum of Natural History.

It is certain that ancestor-worship was an important feature of Yunca religion, for Arriaga, speaking of the Chincha peoples, says that for festivals they gathered in ayllus (tribes or clans), each with mummies of its kinsfolk to which were offered vases, clothes, plumes, and the like. They had household gods (called Conopa or Huasi-camayoc), as distinguished from the communal deities, which were of several classes; more than three thousand of these Conopas it is said, were destroyed by the Spaniards. Garcilasso informs us that each coastal province worshipped a special kind of fish, "telling a pleasant tale to the effect that the First of all the Fish dwells in the sky" a statement which is certainly in tone with a totemic interpretation.

In addition to the special idols of each province, says Garcilasso, 10 all the peoples of the littoral from Truxillo to Tarapaca adored the ocean in the form of a fish, out of gratitude for the food that it yielded, naming it Mama Cocha ("Mother Sea"); and it is indeed plausible that the Food-Giver of the Sea was a great deity in this region, although some of the Truxillo vases seem to indicate that the ocean was also regarded as the abode of dread and inimical monsters, since they portray the conflicts of men or heroes with crustacean and piscine monsters of the deep. Antonio de la Calancha, who was prior of the Augustines at Truxillo in 1619, gives a brief account of the Chimu pantheon. 11 The Ocean (Ni) and the earth (Vis) were worshipped, prayers being offered to the one for fish and to the other for good harvests. The great deity, however, was the Moon (Si), to which sacrifices of children were sometimes made; and this heavenly body, regarded as ruler of the elements and bringer of tempests, was held to be more powerful than the Sun. Possibly the crescent or knife-shaped symbol which appears on the head-gear of vase representations of chieftains, in Truxillo ware, is a token of this cult, which finds a parallel among the Araucanians of the far south, among whom, too, the Moon, not the Sun, is the lofty deity.

The language of the subjects of the Grand Chimu was Mochica, which was unrelated to any other in Peru; but though they regarded the Quichua-speaking Chincha as hereditary enemies, the religious conceptions of the two groups were not very different. In Arriaga's account, 12 the Chincha worshipped the Earth (Mama Pacha) as well as Mama Cocha (the Sea) ; and they also venerated the "Mamas," or Mothers, of maize and cacao. There were likewise tutelary deities for their several villages just as each family had its Penates and Garcilasso states that the god Chincha Camac was adored as the creator and guardian of all the Chincha. The worship of stones in fields and stones in irrigating channels is also mentioned (both for Chimu and for Chincha), and these may well have been in the nature of herms in valleys where fields were narrowly limited; while in addition there were innumerable huacas sacred places, fetishes, oracles, idols, and, in short, anything marvellous, for Garcilasso, in explaining the meaning of the word, says that it was applied to everything exciting wonder, from the great gods and the peaks of the Andes to the birth of twins and the occurrence of hare-lip. It is in this connexion that he speaks of "sepulchres made in the fields or at the corners of their houses, where the devil spoke to them familiarly," a description suggestive of ancestral shrines; and it is quite possible that the word huaca is most properly applied in that sense in which it has survived, to tombs.

In Chincha territory were located the two great shrines of Rimac and Pachacamac, whose oracles even the Incas courted. Rimac, says Garcilasso, signifies "He who Speaks"; he adds that the valley was called Rimac from "an idol there, in the shape of a man, which spoke and gave answers to questions, like the oracle of the Delphic Apollo"; and Lima, which is in the valley of Rimac, receives its appellation from a corruption of this name. A greater shrine, however, and an older oracle was Pachacamac. According to Garcilasso, the word means "Maker and Sustainer of the Universe" (pacha, "earth," camac, "maker"); and he is of opinion that the worship of this divinity originated with the Incas, who, nevertheless, regarded the god as invisible and hence built him no temples and offered him no sacrifices, but "adored him inwardly with the greatest veneration." Markham (not very convincingly) identifies Pachacamac with the great fish-deity of the coast, considering him as a supplanter of the older and purer deity, Viracocha.

One of the most interesting of coastal myths, quoted by Uhle, tells how Pachacamac, having created a man and a woman, failed to provide them with food; but when the man died, the woman was aided by the Sun, who gave her a son and taught the pair to live upon wild fruits. Angered at this interference, Pachacamac killed the youth, from whose buried body sprang maize and other cultivated plants; the Sun gave the woman another son, Wichama, whereupon Pachacamac slew the mother; while Wichama, in revenge, pursued Pachacamac, driving him into the sea, and thereafter burning up the lands in passion, transformed men into stones. This legend has been interpreted as a symbol of the seasons, but it is evident that its elements belong to wide-spread American cycles, for the mother and son suggest the Chibcha goddess, Bachue, while the formation of cultivated plants from the body of the slain youth is a familiar element in myths of the tropical forests and, indeed, in both Americas. From the story it is clear that Pachacamac is a creator god, antagonistic (if not superior) to the Sun, who seems to supplant him in power; but surely it is anomalous that the Earth-Maker should find his end by being driven into the sea unless, indeed, Pachacamac, spouse of Mother Sea, be the embodied Father Heaven, descending in fog and damp and driven seaward by the dispolling Sun. Such an interpretation would make Pachacamac simply a local form of Viracocha; and this, certainly, is suggested in the descriptions, by Garcilasso and others, of the reverence paid to this divinity.

From Francisco de Avila's account 13 of the myths of the Huarochiri, in the valley of the Rimac, "we may infer that Viracocha was known to the Chincha tribes, at one period probably as a supreme god. An idol called Coniraya (meaning according to Markham, "Pertaining to Heat") they addressed as "Coniraya Viracocha," saying, "Thou art Lord of all; thine are the crops, and thine are all the people"; and in every toil and difficulty they invoked this deity for aid.

One of the decorative designs that occurs and recurs on the vases of both the Chimu and Chincha regions in the characteristic style of each is the plumed serpent. What is apparently a modification of this is the man-headed serpent, or the warrior with a serpent's or dragon's tail, a further modification representing the man or deity as holding the serpent in one hand, while frequently, in the other hand, is a symbolic staff or weapon that in certain forms is startlingly like the classical thunderbolt in the hand of Jove. Another step shows only the serpent's head held in the one hand, while the staff, or thunderbolt, is made prominent; and, finally, in the style known as that of Tiahuanaco, from its resemblance to the ancient art of the highlands, a squat deity, holding a winged or snake-headed wand in each hand gives the counterfeit presentment of the central figure on the Tiahuanaco arch and the monolith of Chavin. In Central and North America the plumed serpent is a sky-symbol, associated with rainbow, lightning, rain, and weather; and it is not too much to follow the guesses hitherto ventured that this cycle of images, appearing in various forms in the different periods of Yunca art, is intimately associated with the ancient and nearly universal Jovis Pater of America Father Sky.

PLATE XXXIII: Embroidered figure from a Nasca robe in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Nasca fabrics represent the highest achievement in textile art of aboriginal America. Figures of the type here shown are repeated with minor variations, each, no doubt, of symbolic significance, in a chequered or "all-over" design. The deity represented may be totemic, but obviously belongs to the same group as those shown in such pottery paintings as are represented in Plates XXXII and XXXIV.