|

|

Latin American Mythology

By Hartley Burr Alexander

CHAPTER VI THE ANDEAN NORTH

I The Cultured Peoples of the Andes

II The Isthmians

III El Dorado

IV Myths of the Chibcha

V The Men from the Sea

I. THE CULTURED PEOPLES OF THE ANDES

1 FROM the Isthmus of Panama the western coast of South America is marked by one of the loftiest and most abrupt mountain ranges of the world, culminating in the great volcanoes of Ecuador and the high peaks of western Argentina. A narrow coastal strip, dry and torrid in tropical latitudes; deep and narrow valleys; occasional plateaux or intramontane plains, especially the great plateau of central Bolivia these are the primary diversifications from the high ranges which, rising precipitously on the Pacific side, decline more gradually toward the east into the vast forested regions of the central part of the continent and into the plains and pampas of the south.

Throughout this mountain region, from the plateau of Bogota in the north to the neighbourhood of latitude 30 south, was continued in pre-Columbian times the succession of groups of civilized or semi-civilized peoples of which the most northerly were the Nahua of Mexico, or perhaps the Pueblo tribes of New Mexico. The ethnic boundary of the southern continent is to be drawn in Central America. The Guetare of Costa Rica, and perhaps the Sumo of Nicaragua, constitute northerly outposts of the territorially great Chibchan culture, the centre of which is to be found in the plateau of Bogota, while its southerly extension leads to the Barbacoa of northern Ecuador. South of the Chibcha, in the Andean region lying between the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, is the aboriginal home of the Quechua-Aymara peoples, nearly the whole of which, at the time of the Conquest was embraced in the Empire of the Incas. This empire had even reached into the confines of the third culture area of the southern continent; for the Calchaqui of the mountains of northern Argentina, who were the most representative and probably the most advanced nation of the Diaguite group, had even then passed under Inca subjection. Other tribes of this most southerly of the civilized peoples of America had never been conquered; but bounded, as they were, by the aggressive empire of the north, by the warlike Araucanians to the south, and by the savages of the Gran Chaco to the east, their opportunities for independent development were slight; indeed, it is not improbable that the peoples of this group represent the last stand of a race that had once extended far to the north and had played an important part in the pre-Inca cultures of the central Andes. Beyond the Diaguite lay the domains of savagery, although the Araucanians of the Chilean-Argentine region were not uninfluenced by the northward civilizations and in most respects were superior to the wild tribes that inhabited the great body of the South American continent; but the indomitable love of liberty, which has kept them unconquered through many wars, gave to their territory a boundary-line marked no less by a sharp descent in culture than by its untouched independence.

In Columbian times these three Andean groups the Chibchan tribes, the Quechua-Aymara, and the Diaguite-Calchaqui possessed a civilization marked by considerable advancement in the arts of metallurgy (gold, silver, copper), pottery, and weaving, by agriculture (fundamentally, cultivation of maize), and by domestication of the llama and alpaca. In the art of building, in stone-work, and, generally, in that plastic and pictorial expression which is a sign of intellectual advancement, the central group far excelled its neighbours. Nor was this due to the fact that it alone, under Inca domination, had reached the stage of stable and diversified social organization; for the archaeology of Peru and Bolivia shows that the Empire of the Incas was only the last in a series of central Andean civilizations which it excelled, if at all, in political power rather than in the arts, industrial or aesthetic.

Our knowledge of the religious and mythic ideas of these various groups reflects their relative importance at the time of the Spanish conquests more than their natural diversity. Of the Chibchan groups, only the ideas of a few tribes have been described, and these fragmentarily; of the mythology of the Calchaqui, who had yielded to Inca rule, even less has come down to us; while what is known of the religious conceptions of the pre-Inca peoples of the central region is mainly in the form of gleanings from the works of art left by these peoples, or from such of their cults as survived under the Inca state or in Inca tradition. Inevitably the central body of Andean myth, as transmitted to us, is that of the Incas, who, having reached the position of a great imperial clan, naturally glorified both their own gods and their own legendary history.

II. THE ISTHMIANS

2 The Isthmus of Panama (and northward perhaps as far as the confines of Nicaragua) was aboriginally an outpost of the great Chibchan stock. Tribes of other stocks, some certainly northern in origin, dwelt within the region, but the predominant group was akin to the peoples of the neighbouring southern continent; although whether they were immigrants from the south or were parents of the southern stem can scarcely be known. So far as traditions tell, the uniform account given by the Bolivian tribes is of a northerly origin. The tales seem to point to the Venezuelan coast, and perhaps remotely to the Antilles, rather than to the Isthmus, and it is certain that there are broad similarities in culture especially in the forms and use of ceremonial objects pointing to the remote unity of the whole region from Haiti to Ecuador, and from Venezuela to Nicaragua. It is entirely possible that within this region the drift of influence has been southerly; though it is more likely that counter-streams, northward and southward, must give the full explanation of the civilization.

On the linguistic side it is agreed that the Guetare of Costa Rica represent a branch of the Chibchan stock, while neighbouring tribes of the same stock are either now extinct or little known. The Spanish conquests in the Isthmian region were as ruthlessly complete as anywhere in America, and for the greater part our knowledge of the aborigines is the fruit of archaeology. In the writings of Oviedo and Cieza de Leon some facts may be gleaned enough, indeed, to picture the general character of the rituals of the Indian tribes but there is no competent contemporary relation of the native religion and beliefs.

Oviedo's description 3 of the tribes about the Gulf of Nicoya, where the civilizations of the two Americas meet, indicates a religion in which the great rites were human sacrifices of the Mexican type and feasts of intoxication. Archaeological researches in the same region have brought to light amulets and ornaments, some anthropomorphic in character, but many representing animal forms, usually highly conventionalized alligators, jaguars and pumas, frogs, parrots, vampires, denizens of earth, air, and sea, all indicative of a populous pantheon of talismanic powers; while cruciform, swastika, and other symbolic ornamentation implies a development in the direction of abstraction sustained by Oviedo's mention of "folded books of deerskin parchment," which are probably the southern extension of the art of writing as known in the northern civilization. The archaeology of the Guetare region, in central, and of the Chiriqui region, in southern Costa Rica, disclose the same fantasy of grotesque and conventionalized animals saurians, armadilloes, the cat-tribe, composites indicative of a similarly zoomorphic pantheon. Benzoni, speaking of the tribes of this region, states that they worshipped idols in the forms of animals, which they kept hidden in caves; while Andagoya declares that the priests of the Cuna or Cueva (dwelling at the juncture of the Isthmus and the southern continent) communed with the devil and that Chipiripa, a rain-god, was one of their most important deities; they are said, too, to have known of the deluge. Of the neighbouring Indians, about Uraba, Cieza de Leon gives us to know that "they certainly talk with the devil and do him all the honour they can. . . . He appears to them (as I have been told by one of themselves) in frightful and terrible visions, which cause them much alarm." Furthermore, "the devil gives them to understand that, in the place to which they go [after death], they will come to life in another kingdom which he has prepared for them, and that it is necessary to take food with them for the journey. As if hell was so very far off!"

PLATE XXVI: Jade pendant representing a Vampire. After Hartman, Archaeological Researches on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica, Plate XLIV. For reference to the significance of the bat, as a deity.

Peter Martyr devotes the greater part of a book (the tenth of the Seventh Decade) 4 to a description of the rites and beliefs of the Indians of the region where the Isthmus joins the continent. Dabaiba, he says, was the name both of a river and of a divinity whose sanctuary was about forty leagues from Darien; and thither at certain seasons the caciques, even of the most distant countries, sent slaves to be strangled and burnt before the idol. "When the Spaniards asked them to what divinity they addressed their prayers, they responded that it is to the god who created the heavens, the sun, the moon, and all existing things; and from whom every good thing proceeds. They believe that Dabaiba, the divinity universally venerated in the country, is the mother of this creator." Their traditions told of a great drought which, making the rivers dry, caused the greater part of mankind to perish of thirst, while the survivors emigrated from the mountains to the sea-coast; for this reason they maintained priests and addressed prayers to their divinity, who would seem to be a rain-goddess. Another legend recorded by Peter Martyr tells of a frightful tempest which brought with it two great birds, "similar to the harpies of the Strophades," having "the face, chin, mouth, nose, teeth, eyes, brows, and physiognomy of a virgin." One of these seized the people and carried them off to the mountains to devour them, wherefore, to slay the man-eating bird, certain heroes carved a human figure on the end of a log, which they set in the ground so that the figure alone was visible. The hunters concealed themselves near by, and when the monster, mistaking the image for prey, sunk its talons into the wood, falling upon it, they slew it before it could release itself. "Those who killed the monster were honoured as gods."

Interesting, too, is Martyr's account of the reason given for the sinfulness of incest: the dark spots on the moon represent a man cast into that damp and freezing planet to suffer perpetual cold in expiation of incest committed with his sister the very myth that is told in North Greenland; and the belief that "only nobles have immortal souls" (or, more likely, that they alone enjoy a paradise) is cited to explain why numbers of servants gladly throw themselves into the graves of their masters, since thus they gain the right to accompany their lords into the afterworld of pleasure; all others, apparently, go down to a gloomy hades, though there may be truth in Martyr's statement that it is pollution which brings this fate.

The account of the religion of the Isthmian tribes in later times, by W. M. Gabb andPittier de Fabrega, 5 probably represents faithfully their earlier beliefs. There are deities who are the protectors of game-animals, suggesting the Elders of the Kinds so characteristic of North American lore; though they appear to men in human form, taking vengeance on those who only wound in the chase: "When thou shootest, do it to kill, so that the poor beast doth not fall a prey to the worms," is the command of the King of the Tapirs to the unlucky hunter who is punished for his faulty work by being stricken with dumbness during the period in which a cane grows from a sprout to its full height. The Isthmian peoples recognize (as do most other Americans) a faineant supreme being, Sibu, in the world above, with a host of lesser, but dangerous, powers in the realm of environing nature; and there is a paradise, at least for the noble dead, situated at the zenith, though the way thither is beset by perils, monsters, and precipices. Las Casas also mentions the belief in a supreme deity, Chicuna, Lord of All Things, as extending from Darien to Nicaragua; and he says that along with this god the Sun, the Moon, and the Morning Star were worshipped, as well as divinities of wood and stone which presided over the elements and the sowings (sementeras).

The allusion to deities of the sementeras is interesting in connexion with the Bribri and Brunka (or Boruca) myths, published by Pittier de Fabrega. According to these tribes of Indians, men and animal kinds were originally born of seeds kept in baskets which Sibu entrusted to the lesser gods; but the evil powers were constantly hunting for these seeds, endeavouring to destroy them.

One tale relates that after Sura, the good deity to whom the seed had been committed, had gone to his field of maize, Jaburu, the evil divinity, stole and ate the seed; and when Sura returned, killed and buried him, a cacao-tree and a calabash-tree growing from the grave. Sibu, the almighty one, resolving to punish Jaburu and demanding of him a drink of chocolate, the wives of the wicked deity roasted the cacao, and made a drinking-vessel of the calabash. "Then Sibu, the almighty god, willed and whatever he wills has to be: 'May the first cup come to me!' and as it so came to pass, he said, 'My uncle, I present this cup to thee, so that thou drink!' Jaburu swallowed the chocolate at once, with such delight that his throat resounded, tshaaa! And he said, 'My uncle! I have drunk Sura's first fruit!' But just at this moment he began to swell, and he swelled and swelled until he blew up. Then Sibu, the almighty god, picked up again the seed of our kin, which was in Jaburu's body, and willed, 'Let Sura wake up again!' And as it so happened he gave him back the basket with the seed of our kin to keep."

In another tale a duel between Sibu and Jaburu, in which each should throw two cacao-pods at the other, and he should lose in whose hand a pod first broke, was the preliminary for the creation of men, which Sibu desired and Jaburu opposed. The almighty god chose green pods, the evil one ripe pods; and at the third throw the pod broke in Jaburu's hand, mankind being then born from the seed. A third legend, of a man-stealing eagle who devoured his prey in company with a jaguar (who is no true jaguar, but a bad spirit, having the form of a stone until his prey approaches), is evidently a version of the story of the bird-monster told by Peter Martyr.

III EL DORADO

Not the quest of the Golden Fleece itself and the adventures of the Argonauts with clashing rocks and Amazonian women are so filled with extravagance and peril as is the search for El Dorado. 6 The legend of the Gilded Man and of his treasure city sprang from the soil of the New World in the very dawn of its discovery whether wholly in the imaginations of conquistadores dazzled with dreams of gold, or partly from some custom, tale, or myth of the American Indians it is now impossible to say. In its earlier form it told of a priest, or king, or priest-king, who once a year smeared his body with oil, powdered himself with gold dust, and in gilded splendour, accompanied by nobles, floated to the centre of a lake, where, as the onlookers from the shore sang and danced, he first made offering of treasure to the waters .and then himself leaped in to wash the gold from his body. Later, fostered by the readiness of the aborigines to rid themselves of the plague of white men by means of tales of treasure cities farther on, the story grew into pictures of the golden empire of Omagua, or Manoa, or Paytiti, or Enim, on the shores of a distant lake. Expedition after expedition journeyed in quest of the fabled capital. As early as 1530, Ambros von Alfinger, a German knight, set out from the coast of Venezuela in search of a golden city, chaining his enslaved native carriers to one another by means of neck-rings and cutting off the heads of those who succumbed to fatigue to save the trouble of unlinking them; Alfmger himself was wounded in the neck by an arrow and died of the wound. In 1531 Diego de Ordaz conducted an expedition guided by a lieutenant who claimed to have been entertained in the city of Omoa by El Dorado himself; in 1536-38 George of Spires, afterward governor of Venezuela, made a journey of fifteen hundred miles into the interior; and another German, the red-bearded Nicholas Federman, departed upon the same quest. On the plains of Bogota in 1539 they met Quesada and Belalcazar, who, coming from the north and from the south respectively, had subdued the Chibcha realm. Hernan Perez de Quesada, brother of the conqueror, led an unlucky expedition, behaving with such cruelty that his death from lightning was regarded as a divine retribution; while the expeditions of the chivalrous Philip von Hutten (1540-41) and of Orellana down the Amazon (1540-41) were followed by others, down to the time of Sir Walter Raleigh's quest in 1595, all enlarging the geographical knowledge of South America and accumulating fables of cities of gold and nations of warlike women. Of all these adventures, however, the most amazing was the "Jornada de Omagua y Dorado" which set out from Peru in 1559 under the leadership of Don Pedro de Ursua, a knight of Navarre. Ursua was a gentleman, worthy of his knighthood, but his company was crowded with cut-throats, of whom he himself was an early victim. Hernando de Guzman made himself master of the mutineers, and renouncing allegiance to the King of Castile, proclaimed himself Prince and King of all Tierra Firme; but he, in turn fell before his tyrant successor, Lope de Aguirre, whose fantastic and blood-thirsty insanity caused half the continent to shudder at his name, which is still remembered in Venezuelan folk-lore, where the phosphorescence of the swamp is called juego de Aguirre in the belief that under such form the tortured soul of the tyrant wanders abroad.

The true provenance of the story of the Gilded Man (if not of the treasure city) seems certainly to be the region about Bogota in the realm of the Chibcha. Possibly the myth may refer to the practices of one of the nations conquered by the Muyscan Zipas before the coming of the Spaniards, and legendary even at that time; for as the tale is told, it seems to describe a ceremony in honour of such a water-spirit as we are everywhere told the Colombian nations venerated; and it may actually be that the Gilded Man was himself a sacrifice to or a personation of the deity. Whatever the origin, the legends of El Dorado have their node in the lands of the Chibcha a circumstance not without its own poetic warrant, for from no other American people have jewelleries of cunningly wrought gold come in more abundance.

The Zipa of Bogota, at the period of the conquest, was the most considerable of the native rulers in what is now Colombia, having an empire only less in extent than those of the Peruvian Incas and of the Aztec Kings. He also was a recent lord, engaged at the very time of the coming of the whites in extending his power over neighbouring rulers; it is probable that Guatavita, east of Bogota had fallen to the Zipa not many decades before the conquest and this Guatavita is supposed to have been the scene of the rite of El Dorado; in any case it had remained a famous shrine. Tunja was another power to the east of Bogota declining before the rising power of the Zipas, its Zaque (as the Tunjan caciques were called) being saved from the Zipa's forces by the arrival of the Spaniards.

Besides these the Chibcha proper 7 there were in Colombia in the sixteenth century other civilized peoples, akin in culture and language, whose chief centres were in the elongated Cauca valley paralleling the Pacific coast.

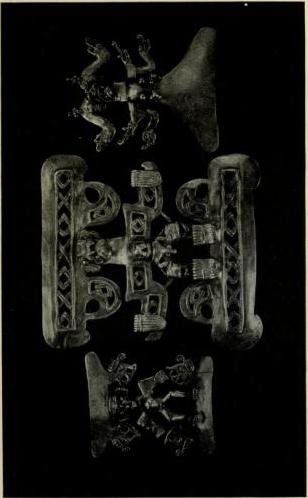

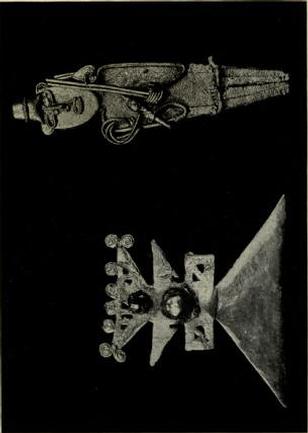

PLATE XXVII: (A) Colombian gold work. Ornaments in the forms of human and monstrous beings, doubtless mythological subjects. The originals are in the American Museum of Natural History.

(B) Colombian gold work. The human figure apparently holds a staff or wand and may represent Bochica or similar personage. The originals are in the American Museum of Natural History.

Farthest north were the tribes in the neighbourhood of Antioquia theTamahi and Nutabi; south of these, about Cartago, were the most famous of gold-workers, the Quimbaya; while near the borders of what is now Ecuador dwelt the Coconuco and their kindred. All these peoples possessed skill in pottery, metal-working, and weaving; and the inhabitants of the Cauca valley were the most advanced of the Colombians in these arts. Indeed, the case of Peru seems to be in a measure repeated; for the Chibcha surpassed their neighbours in the strength of their military and political organization rather than in their knowledge of the arts.

It is even possible that the Chibcha had been driven eastward by the western tribes, for the inhabitants of the Cauca valley possessed traditions of a northern origin, claiming to be immigrants; while the Chibcha still regarded certain spots in the territories of their western enemies, the Muzo, as sacred. Little is known of the mythic systems of any of these peoples save the Chibcha. The Antioquians preserved a deluge-myth (as doubtless did all the other Colombians); and they recognized a creator-god, Abira, a spirit of evil, Canicuba, and a goddess, Dabeciba, who was the same as Dabaiba, the Darien Mother of the Creator. Cieza de Leon says 8 that the Antioquians "carve the likeness of a devil, very fierce and in human form, with other images and figures of cats which they worship; when they require water or sunshine for their crops, they seek aid from these idols."

Of the Quimbaya Cieza tells how there appeared to a group of women making salt beside a spring the apparition of a disembowelled man who prophesied a pestilence that soon came. "Many women and boys affirmed that they saw the dead with their own eyes walking again.

These people well understand that there is something in man besides the mortal body, though they do not hold that it is a soul, but rather some kind of transfiguration." The Sun, the Moon, and the Rainbow were important divinities with all these tribes, and they made offerings of gold and jewels and children to water-spirits in rivers and in springs. Human sacrifice was probably universal, and too many of the Indians, as Cieza puts it, "not content with natural food, turned their bellies into tombs of their neighbours."

IV. MYTHS OF THE CHIBCHA

9 Fray Pedro Simon wrote his Noticias Historiales in 1623, some four score years from the conquest, giving in his fourth Noticia an account of the myths and rites of the Chibcha which is our primary source for the beliefs of these tribes. Like other American peoples the Chibcha recognized a Creator, apparently the Heaven Father, but like most others their active cults centred about lesser powers: the Sun (to whom human sacrifices were made), the Moon, the Rainbow, spirits of lakes and other genii locorum, culture deities, male and female, and the manes of ancestors. Idols of gold and copper, of wood and clay and cotton, represented gods and fetishes, and to them offerings were made, especially of emeralds and golden ornaments. Fray Pedro says that thePijaos aborigines and some of those of Tunja had in their sanctuaries images having three heads or three faces on a single body which, the natives said, represented three persons with one heart; and he also records their use of crosses to mark the graves of those dead of snake-bite, as well as their belief that the souls of the dead fared to the centre of the earth, crossing the Stygian river on balsas made of spiders' webs, for which reason spiders were never killed. Like the Aztec they held that the lot of men slain in battle and of women dying in child-birth was especially delectable in the other world.

The worship of mountains, serpents, and lakes was implied in many of the Chibcha rites. Slaves were sacrificed, and their bodies were buried on hill-tops; children, who were the particular offering to the Sun, were sometimes taken to mountain- tops to be slain, their bodies being supposed to be consumed by the Sun; and an interesting case of the surrogate for human victims was the practice of sacrificing parrots which had been taught to speak. In masked dances, addressed to the Sun, tears were represented on the masks as a supplication for pity; and another curious rite, apparently solar, was performed at Tunja, where twelve men in red, presumably typifying the moons of the year, danced about a blue man, who was doubtless the sky-god. The ceremony of El Dorado is only one of many rites in which the divinities of the sacred lakes were propitiated; and it is probable that these water-spirits were conceived in the form of snakes, as when, at Lake Guatavita, a huge serpent was supposed to issue from the depths to secure offerings left upon the bank.

The same concept of serpentiform water-deities appears in the curious and novel creation-myth of the Chibcha, briefly told by Fray Simon. In the beginning all was darkness, for light was imprisoned in a great house in charge of a being called Chiminigagua, whom the friar names as the Supreme God, omnipotent, ever good, and lord of all things. After creating huge black birds, to whom he gave the light, commanding them to carry it in their beaks until all the world was illumined and resplendent, Chiminigagua formed the Sun, the Moon (to be the Sun's wife and companion), and the rest of the universe. The human race was of another origin, for shortly after the creation of light, from Lake Iguaque, not far from Tunja, emerged a woman named Bachue or Turachogue ("the Good Woman"), bearing with her a boy just out of infancy. When he was grown, Bachue married him; and their prolific offspring she brought forth four or six children at a birth peopled the earth; but finally the two returned beneath the waters, Bachue enjoining upon the people to keep the peace, to obey the laws which she had given them, and in particular to preserve the cult of the gods; while the pair assumed the form of serpents, in which they were supposed sometimes to reappear to their worshippers.

The belief that the ancestors of men issued from a lake or spring was common to many Andean tribes, being found far to the south, where the Indians of Cuzco pointed to Lake Titicaca as the place whence they had come. The myth is easy to explain for the obvious reason that lakesides are desirable abodes and that migrating tribes would hark back to abandoned lakeside homes as their primal sites; however, another suggestion is made plausible by various fragments of origin-myths which have been preserved, namely, that the Andean legends belong to the great cycle of American tales which make men immigrants to the upper world from an under-earth realm whence they have been driven by the malevolence of the water-monster, a serpent or a dragon. There are many striking parallels between the Colombian tales and those of the Pueblo tribes of North America the great underworld-goddess, the serpent and the spider as subaqueous and subterranean powers, the return of the dead to the realm below, the importance of birds in cosmogony, the cult of the rainbow; and along with these there are tales of a culture hero and of a pair of divine brothers such as are common to nearly all American peoples.

Other Colombian legends of the origin of men include the Pijaos belief, recorded by Fray Simon, that their ancestors had issued from a mountain, and the tradition of the Muzo western neighbours of the Chibcha that a shadow, Are formed faces from sand, which became men and women when he sprinkled them with water. A true creation-story (as distinguished from tales of origin through generation) was told also by the people of Tunja. In the beginning all was darkness and fog, wherein dwelt the caciques of Ramiriqui and of Sogamozo, nephew and uncle. From yellow clay they fashioned men, and from an herb they created women; but since the world was still unillumined, after enjoining worship upon their creatures, they ascended to the sky, the uncle to become the Sun, the nephew the Moon.

It was at Sogamozo that the dance Q{ the twelve red men each garlanded and carrying a cross, and each with a young bird borne as a crest above his head was danced about the blue sky-man, while all sang how human beings are mortal and must change their bodies into dust without knowing what shall be the fate of their souls.

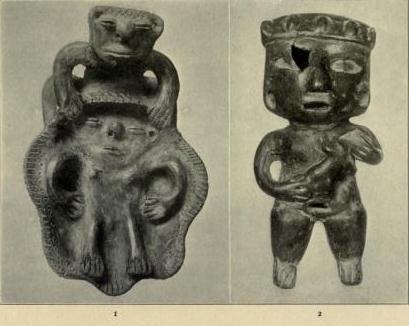

PLATE XXVIII: 1. Ceremonial dish of black ware with monster or animal forms found near Anoire, Antioquia. The original is in the Museum of the University of Nebraska.

2. Image of mother and child, red earthenware, from the coastal regions of Colombia. The original is in the Museum of the University of Nebraska.

Fray Simon relates an episode of these same Indians which is enlightening both as to the missionary and as to the aboriginal conception of the powers that be. After the first missionary had laboured among the natives of Tunja and Sogamozo, "the Demon there began to give contrary doctrines; and among other matters he sought to discredit the teaching of the Incarnation, telling them that such a thing had not yet taken place. Nevertheless, it should happen that the Sun, assuming human flesh in the body of a virgin of the pueblo of Guacheta, should cause her to bring forth that which she should conceive from the rays of the sun, although remaining virgin. This was bruited throughout the provinces, and the cacique of the pueblo named, wishing to prove the miracle, took two virgins, and leading them forth from his house every dawn, caused them to dispose themselves upon a neighbouring hill, where the first rays of the sun would shine upon them. Continuing this for some days, it was granted to the Demon by Divine permission (whose judgements are incomprehensible) that the event should issue according to his desire: in such manner that in a few days one of the damsels became pregnant, as she said, by the Sun." At the end of nine months the girl brought forth a hacuata, a large and beautiful emerald, which was treated as an infant, and after being carried for several days, became a living creature "all by the order of the Demon." The child was called Goranchacha, and when he was grown he became cacique, with the title of "Child of the Sun." It is to be suspected that the story of the virgin-born son of the Sun was older than the first preaching of the Incarnation, and that Spanish ears had too eagerly misheard some tale of rites or myths which must have been analogous to the Inca legends of descent from the Sun and to their consecration of virgins to his worship.

Like the other civilized American nations the Chibcha preserved the tradition of a bearded old man, clothed in long robes who came from the east to instruct them in the arts of life and to raise them from primeval barbarism; and like other churchly writers Fray Pedro Simon regarded this as evidence of the preaching of the Gospel by an apostle. Nempterequeteva, or Nemquetheba, and Xue, or Zuhe, are two of the names of this culture hero, worshipped as the god Bochica. He taught the weaving of cotton, the cultivation of fruits, the building of houses, the adoration of the gods; and then he passed on his mysterious way, leaving as proof of his mission designs of crosses and serpents, and the custom of erecting crosses over the graves of the victims of snake-bite to Fray Pedro an obvious reminiscence of the brazen serpent raised on a cross by Moses in the Wilderness. One of the epithets of this greybeard was Chiminizagagua, or "Messenger of Chiminigagua," the supreme god; and when the Spaniards appeared they were called Gagua, after the light-giver; but later, when their cruelties had set them in a different context, the aborigines changed the name to Suegagua ("Demon with Light") after their principal devil, Suetiva, "and this they give today to the Spaniards." Piedrahita says the Spaniards were termed Zuhd y but he identifies the name as belonging to the hero Bochica.

A curious episode follows the departure of the culture hero. Among the people appeared a woman, beautiful and resplendent "or, better to say, a devil in her figure" who taught doctrines wholly opposed to the injunctions of Chiminizagagua. Dancing and carousal were the tenets of her evangel; and in displeasure at this, Chiminizagagua transformed the woman (variously known as Chie, Huytaca, or Xubchasgagua) into an owl, condemning her to walk the night. Humboldt says that Bochica changed his wife Chia into the Moon (chia signifies "moon" in the Chibchan tongue, says Acosta de Samper); and it seems altogether likely that in the culture hero, Messenger of Light, and the festal heroine, with their opposite doctrines, we have a myth of sun and moon.

The Chibcha, of course, had their deluge-legend. In the version given by Fray Pedro Simon it is associated with the appearance of the rainbow as the symbol of hope; and since the rainbow cult was important throughout the Andean region, it may everywhere have been associated with some such myth as the friar recounts. Chibchachum, the tutelary of the natives of Bogota, being offended by the people, who murmured against him and indeed openly offended, sent a flood to punish them, whereupon they, in their peril, appealed to Bochica, who appeared to them upon a rainbow, and, striking the mountains with his staff, opened a conduit for the waters. Chibchachum was punished, as Zeus punished the Titans, by being thrust beneath the earth to take the place of the lignum-vitae-trees which had hitherto upheld it, and his weary restlessness is the cause of earthquakes; while the rainbow, Chuchaviva, was thenceforth honoured as a deity, though not without fear; for Chibchachum, in revenge for his disgrace, announced that when it appeared, many would die. In the version of this tale given by Piedrahita, Huytaca plays a part, for it is as a result of her artifices that the waters rise; but Bochica is again the deliverer, and the place opened for the issuance of the waters was shown at the cataract of Tequendama one of the wonders of the world."

The myth of Chibchachum, shaking the world which he supports, has its analogue not only in the tale of Atlas but also in the Tlingit legend of the Old Woman Below who jars the post that upholds the world. It would seem, however, not impossible that the story is an etymological myth, for Fray Pedro Simon says that Chibchachum means "Staff of the Chibcha," a name which might easily lend itself to the mythopoesy of the deluge-tale; nor is it unreasonable from the point of view of cultural advancement, for the Chibcha were beyond the stage in which it is profitable to refer all deifications to natural phenomena. Chibchachum, says the friar, was god of commerce and industries a complex divinity, not a mere hero of myth and Bochica, the most universally venerated of Chibchan deities, was revered as a law-giver, divinity of caciques and captains; served with sacrifices of gold and tobacco, he was worshipped with fasts and hymns, and his image was that of a man with the golden staff of authority. There was a fox-god and a bear-god, but Nemcatacoa, the bear-god, was patron of weavers and dyers, and, oddly, of drunkards; in his bear's form he was supposed to sing and dance with his followers. Chukem, deity of boundaries and foot-races, must have been an American Hermes, and Bachue, goddess of agriculture and of the springs of life, was, no doubt, a personification of the earth itself, a Ge or Demeter. Chuchaviva, the Rainbow, aided women in child-birth and those sick with a fever and we think of the images of the rainbow goddess on the sweat lodges of the Navaho far to the north, and of the rainbow insignia of the royal Incas in the imperial south. Certain it is that here we have to do with a pantheon that reflects the complexity of a life developed beyond the primitive needs of those whom we call nature-folk.

V. THE MEN FROM THE SEA

The most picturesque account of the landing of gigantic strangers on the desert-like Pacific coast, just south of the equator, is that given by Cieza de Leon. 10 "I will relate what I have been told, without paying attention to the various versions of the story current among the vulgar, who always exaggerate everything." With this proclamation of modesty, he proceeds with the tale which the natives, he says, have received from their ancestors of a remote time.

"There arrived on the coast, in boats made of reeds, as big as large ships, a party of men of such size that, from the knee downwards, their height was as great as the entire height of an ordinary man, though he might be of good stature. Their limbs were all in proportion to the deformed size of their bodies, and it was a monstrous thing to see their heads, with hair reaching to the shoulders. Their eyes were as large as small plates. They had no beards and were dressed in the skins of animals, others only in the dress which nature gave them, and they had no women with them. When they arrived at this point [Santa Elena], they made a sort of village, and even now the sites of their houses are pointed out. But as they found no water, in order to remedy the want they made some very deep wells, works which are truly worthy of remembrance, for such is their magnitude that they certainly must have been executed by very strong men. They dug these wells in the living rock until they met with water, and then they lined them with masonry from top to bottom in such sort that they will endure for many ages. The water in these wells is very good and wholesome, and always so cold that it is very pleasant to drink it. Having built their village and made their wells or cisterns where they could drink, these great men, or giants, consumed all the provisions they could lay their hands upon in the surrounding country, insomuch that one of them ate more meat than fifty of the natives of the country could. As all the food they could find was not sufficient to sustain them, they killed many fish with nets and other gear. They were detested by the natives, because in using their women they killed them, and the men also in another way; but the Indians were not sufficiently numerous to destroy this new people who had come to occupy their lands. . . . All the natives declare that God, our Lord, brought upon them a punishment in proportion to the enormity of their offence. ... A fearful and terrible fire came down from heaven with a great noise, out of the midst of which there issued a shining angel with a glittering sword, with which, at one blow, they were all killed, and the fire consumed them. There only remained a few bones and skulls, which God allowed to remain without being consumed by the fire, as a memorial of this punishment."

Cieza de Leon's story is only one among a number of accounts of this race of giants, come from the sea and destroyed long ago by flame from heaven for the sin of sodomy. To these legends recent investigations have added a new interest; for during excavations in the coast region to the north of Cape Santa Elena the members of the George G. Heye Expeditions (1906-08) discovered the remains of a unique aboriginal civilization in this region, among its monuments being stone-faced wells corresponding to those mentioned by the early narration. Another and peculiarly interesting type of monument, found here in abundance, is the stone seat, whether throne or altar, carved with human or animal figures to support it, and reminiscent of the duhos of the Antilles and of carved metates and seats found northward in the continent and beyond the Isthmus. It is the opinion of the excavators that these seats were thrones for deities; possibly also for human dignitaries, especially as clay figures represent men sitting upon such seats images, perhaps, of household gods; while the figures of men, pumas, serpents, birds, monkeys, and other figures crouching caryatid-like are, no doubt, depictions of supporting powers, divine auxiliaries or gods themselves. Monstrous forms, composite animals, and grotesquely frog-like images of a female goddess in bas-relief on stele-like slabs mute emblems of a forgotten pantheon add curious interest to the vanished race, remembered only in distorted legend when the first-coming Spaniards received the tale from the aborigines.

Juan de Velasco11 in the beginning of his history of Quito, places the coming of the giants about the time of the Christian era; and six or seven centuries later, he declares, another incursion of men from the sea appeared on this coast, destined to leave a more permanent trace, for the present city of Caraques not only marks the site of their first power, but bears the name of the Cara. These invaders are said to have come on balsas the strange boats of this coast, formed of logs bound together, the longest at the centre, into the form of a hull, on which a platform was built, while masts bore cloth sails; and it is stated that the Spaniards encountered such craft capable of carrying forty or fifty men.

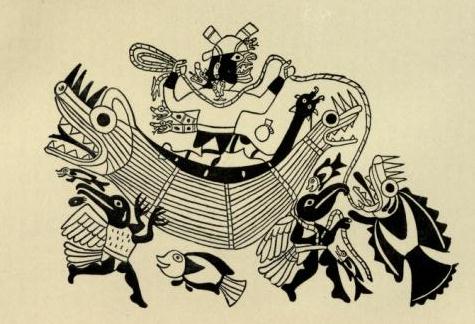

PLATE XXIX: Scene from a vase, Truxillo, showing balsa. The drawing is in the Chimu style. After Joyce, South American Archaeology, page 126.

The Cara were an adventurous people, and after dwelling for a time upon the coast, they advanced into the interior until, about 980 A. D., according to Velasco, they eventually established their power in the neighbourhood of Quito, where the Scyri (as the Cara king was called) became a powerful overlord. From that time until Quito was subdued by the Incas Tupac Yupanqui and Huayna Capac in the latter part of the fifteenth century, the Scyris reigned over the northern empire, constantly extending their territories by war; but their power was finally broken when the Inca added the emerald of the Scyris to the red fringe of Cuzco to complete his imperial crown.

The followers of the Scyris, Velasco says, were mere idolaters, having at the head of their pantheon the Sun and the Moon who had guided them on their journeys; and he describes the temples built to these deities on two opposite hills at Quito, that to the Sun having before the door two pillars which served to measure the solar year, while twelve lesser columns indicated the beginning of each month. Elsewhere in their empire were the usual local cults, worship of animals and elements, with tales of descent from serpentiform water-spirits and with adoration of fish and of food animals while on the coast the Sea was a great divinity, and the islands of Puna and La Plata were the seats of famous sanctuaries, at the former shrine prisoners being sacrificed to Tumbal, the war-god, by having their hearts torn out. The neighbouring coast was the seat of the veneration of the great emerald (mentioned by Cieza de Leon and Garcilasso de la Vega) which was famous as a god of healing; and it is altogether probable that the Scyris brought their regard for the emerald from this region in which the gem abounded, though this may well have been merely a local intensification of that belief in the magic of green and blue gems which is broadcast in the two Americas.

Besides the stories of the giants and the Cara, there is a third legend of an ancient descent of seamen upon the equatorial coast. Balboa 12 is the narrator of the tale of the coming of Naymlap and his people to Lambeyeque, a few degrees south of Cape Santa Elena, and the story which he tells is given with a minuteness as to name and description that leaves no doubt of its native origin. At a very remote period there arrived from the north a great fleet of balsas, commanded by a brave and renowned chieftain, Naymlap. His wife was called Ceterni, and a list of court officers is given Pitazofi, the trumpeter; Ninacolla, warden of the chief's litter and throne; Ninagentue, the cup-bearer; Fongasigde, spreader of shell-dust before the royal feet (a function which leads us to suspect that the royal feet, for magic reasons, were never to touch the earth); Ochocalo, chief of the cuisine; Xam, master of face-paints; and Llapchilulli, charged with the care of vestments and plumes. From this account of the entourage, one readily infers that the chieftain is more than man, himself a divinity; and, indeed, Balboa goes on to say that immediately after the new comers had landed, they built a temple, named Chot, wherein they placed an idol which they had brought and which, carved of green stone in the image of the chief, was called Llampallec, or "figure of Naymlap." After a long reign Naymlap disappeared, leaving the report that, given wings by his power, he had ascended to the skies; and his followers, in their affliction, went everywhere in search of their lord, while their children inhabited the territories which had been acquired. Cium, the successor of Naymlap, at the end of his reign, immured himself in a subterranean chamber, where he perished of hunger in order that he might leave the reputation of being immortal; and after Cium were nine other kings, succeeded by Tempellec, who undertook to move the statue of Naymlap. But when a demon, in the form of a beautiful woman, had seduced him, it began to rain a thing hitherto unknown on that dry coast and continued for thirty days, this being followed by a year of famine, whereupon the priests, binding Tempellec hand and foot, cast him into the sea, after which the kindgom was changed into a republic.

This tale bears all the marks of authentic tradition. We may well suppose that Naymlap and his successors were magic kings, reigning during the period of their vigorous years and then sacrificed to make way for a successor who should anew incarnate the sacred life of Llampallec. Such rulers, as corn-spirits and embodiments of the communal soul of their people, have been made familiar by Sir James G. Frazer's monumental Golden Bough; and in this case it would appear that the sacred king was regarded as a marine divinity, probably as the son of Mother Sea. Certainly this would not merely explain the shell-dust spread beneath his feet, but it might also account for the punishment of Tempellec, who had brought the cataclysm of water to the land and so was cast back to his own element; while it is even possible that the worship of the emerald, which all writers mention in connexion with this coast, may have here received its especial impetus from the colour and translucency of the stone, suggesting the green waters of the ocean.

NOTES

I. The ethnology of the Andean region is treated by Joyce [c], Wissler, The American Indian, and Beuchat, II. iv. Bastian, Culture and History, give more extended views; while tribal distribution in its cultural relations is probably best presented by Schmidt, in ZE xlv. Spinden, "The Origin and Distribution of Agriculture in America," and Means, "An Outline of the Culture-Sequence in the Andean Area," both in CA xix (Washington, 1917), are significant contributions to the problem of origins and history; with these should be placed, "Origenes Etnograficos de Colombia," by Carlos Cuervo Marquez, in the Proceedings of the Second Pan American Scientific Congress, i (Washington, 1917). Spinden conceives an archaic American culture, probably originating in Mexico and thence spreading north and south, which was based upon agriculture and characterized by the use of pottery, textiles, etc., and which, in the course of time, made its influence felt from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to that of La Plata. This hypothesis admirably accounts for the obvious affinities of the civilizations of the two continents.

2. The linguistic and cultural affinities of the Isthmian tribes are described by Wissler, Beuchat, Joyce [c], and Thomas and Swanton; and on the archaeological side especially by Hartman [a], [b], and Holmes [c], [d]. For the broader analogies of the Central American, North Andean, and Antillean regions see also Saville, Cuervo Marquez, and Spinden's article mentioned in Note I, supra, Spinden, Maya Art (MPM), argues against the conception of extensive borrowing. Of the earlier authorities for this region, the important are Peter Martyr, Benzoni, Oviedo, Herrera, and Las Casas. Among writers of later times, Humboldt holds first place.

3. Oviedo (TC), pp. 211-22. Other references in this paragraph are: Benzoni (HS), ii; Andagoya (HS), pp. 14-15; Cieza de Leon, 1864, ch. viii.

4. Peter Martyr, 1912, ii (pp. 319, 326 quoted).

5. Gabb, pp. 503-06; Pittier de Fabrega [b], pp. 1-9; Las Casas [b], ch. cxxv.

6. The most recent work, summarizing the legend of El Dorado, is Zahm [b]; and the earliest versions of the tale are those of Simon, Fresle, Piedrahita, Cavarjal, and Castellanos, the latter of whom incorporated the story in his poetical Elejias de Farones Ilustres de Indias, which was printed at Madrid, in 1850. Critical accounts, in addition to Zahm, are Bollaert's "Introduction" to Simon's Expedition of Pedro de Ursua (Spanish in Serrano y Sanz, Historiadores de Indias, ii) and in Bandelier's The Gilded Man. On the historical side, especially as regards the period of the Conquest, Andagoya, Castellanos, Carvajal, Fresle, Simon, give unforgettable pictures of the adventurous extravagance and bizarrerie of a time scarcely to be paralleled in human annals. Father Zahm's Quest of El Dorado is an inviting introduction to this literature.

7. For Chibchan ethnology and archaeology, see Joyce [c], Acosta de Samper, and Cuervo Marquez.

8. Cieza de Leon (#S), 1864, pp. 59, 88, 101.

9. The primary sources for the mythology of the Chibchan tribes at the time of the Conquest are Pedro Simon, Lucas Fernandez Piedrahita (especially I, iii, iv), and Cieza de Leon. Simon's "Cuarta Noticia," in eighteen chapters, is the fullest exposition of Chibcha beliefs and history; along with the "Tercera Noticia" it is printed in Kingsborough, viii, which is here cited (pp. 244, 263-64 quoted). Other authorities include Humboldt, Joyce [c], chh. i, ii; Acosta de Samper, ch. viii; Sir Clements Markham, art. "Andeans," in ERE; and Beuchat, pp. 549-50. On the deluge myth see also Bandelier [c].

10. The story of the giants is given by Cieza de Leon [a], ch. Hi; see also Velasco, p. 12; Bandelier [b], where the literature of the subject is assembled; and Saville, 1907, p. 9. The archaeology of the region, with numerous plates, is presented in Saville's reports; ii. 88-123 ( I 9 I ) contains a description and discussion of the stone seats; while brief accounts are to be found in Beuchat and in Joyce [c].

11. Velasco is the chief authority for the career of the people of Cara. The discoveries of Dorsey on the island of La Plata give an added significance to these tales of men from the sea.

12. Balboa (TC), ch. vii; cf. Joyce [c], ch. iii.