|

|

Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion

Jane Ellen Harrison

1903

CHAPTER IV.

THE WOMEN'S FESTIVALS

THESMOPHORIA, ARREPHORIA, SKIROPHORIA, STENIA, HALOA

The Megara| The Nesteia | Arrephoria | Meaning of Thesmophoria | The Curse And The Law | The Haloa | The Eleusinian Mysteries | The Tokens | The Kernophoria | Purification and Sacrifice

The Thesmophoria

WITH the autumn festival of the Thesmophoria we come to a class of rites of capital interest. They were practised by women only and were of immemorial antiquity. Although, for reasons explained at the outset, they are considered after the Anthesteria and Thargelia, their character was even more primitive, and, owing to the conservative character of women and the mixed contempt and superstition with which such rites were regarded by men, they were preserved in pristine purity down to late days. Unlike the Diasia, Anthesteria, Thargelia, they were left almost uncontaminated by Olympian usage, and a point of supreme interest under the influence of a new religious impulse, they issued at last in the most widely influential of all Greek ceremonials, the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Kathodos and Anodos

To the primitive character and racial origin of these rites we have the witness of Herodotus, though unhappily piety sealed his lips as to details. He says, 'Concerning the feast of Demeter which the Greeks call Thesmophoria I must preserve an auspicious silence, excepting in so far as every one may speak of it. It was the daughters of Danaus who introduced this rite from Egypt and taught it to the Pelasgian women; but after the upset of the whole of Peloponnesos by the Dorians the rite died down completely, and it was only those of the Peloponnesians who were left, and the Arcadians who did not leave their seats who kept it up. Herodotus oddly enough does not mention the Athenians, who were as stable and as untouched as the Arcadians, but his notice is invaluable as fixing the pre-Dorian character of the rites. Knowing that they were of immemorial antiquity, more suo he attributes them to the Egyptians, and as will later be seen there may be some element of probability in his supposition.

The Thesmophoria, like the Anthesteria, was a three days' festival. It was held from the llth 13th of Pyanepsion (October November); the first day, the llth, was called both Kathodos and Anodos, Downgoing and Uprising, the second Nesteia, Fasting, and the third Kalligeneia, Fair-Born or Fair-Birth. The meaning of the name Thesmophoria and the significance of the three several days will appear later: at present it is sufficient to note that the Thesmophoria collectively was a late autumn festival and certainly connected with sowing. Cornutus says, 'they fast in honour of Demeter. . .when they celebrate her feast at the season of sowing.' Of a portion of the ritual of the Thesmophoria we have an unusually detailed account preserved to us by a scholiast on the Hetairae of Lucian; and as this portion is, for the understanding of the whole festival, of capital importance it must at the outset be examined in detail. In the dialogue of Lucian, Myrto is reproaching Pamphilos for deserting her; 'the girl,' says Myrto, 'you are going to marry is not good-looking; I saw her close at hand at the Thesmophoria with her mother.' The notice is important as it has been asserted that the Thesmophoria was a festival of married women only, which, in Lucian's time, was clearly not the case.

The scholiast on the passage comments as follows, and ancient commentators have left us few commentaries more instructive:

'The Thesmophoria, a festival of the Greeks, including mysteries, and these are called also Skirrophoria. According to the more mythological explanation they are celebrated in that Kore when she was gathering flowers was carried off by Plouton. At the time a certain Eubouleus, a swineherd, was feeding his swine on the spot and they were swallowed down with her in the chasm of Kore. Hence in honour of Eubouleus the swine are thrown into the chasms of Demeter and Kore. Certain women who have purified themselves for three days and who bear the name of 'Drawers up' bring up the rotten portions of the swine that have been cast into the m.egara. And they descend into the inner sanctuaries and having brought up (the remains) they place them on the altars, and they hold that whoever takes of the remains and mixes it with his seed will have a good crop. And they say that in and about the chasms are snakes which consume the most part of what is thrown in; hence a rattling din is made when the women draw up the remains and when they replace the remains by those well-known (tceiva) images, in order that the snakes which they hold to be the guardians of the sanctuaries may go away.

'The same rites are called Arretophoria (carrying of things unnamed) and are performed with the same intent concerning the growth of crops and of human offspring. In the case of the Arretophoria, too, sacred things that may not be named and that are made of cereal paste, are carried about, i.e. images of snakes and of the forms of men. They employ also fir-cones on account of the fertility of the tree, and into the sanctuaries called megara these are cast and also, as we have already said, swine the swine, too, on account of their prolific character in token of the growth of fruits and human beings, as a thank-offering to Derneter, inasmuch as she, by providing the grain called by her name, civilized the human race. The interpretation then of the festival given above is mythological, but the one we give now is physical. The name Thesmophoria is given because Demeter bears the title Thesmophoros, since she laid down a law or Thesmos in accordance with which it was incumbent on men to obtain and provide by labour their nurture.'

The main outline of the ritual, in spite of certain obscurities in the scholiast's account, is clear. At some time not specified, but during the Thesmophoria, women, carefully purified for the purpose, let down pigs into clefts or chasms called jieyapa or chambers. At some other time not precisely specified they descended into the megara, brought up the rotten flesh and placed it on certain altars, whence it was taken and mixed with seed to serve as a fertility charm. As the first day of the festival was called both Kathodos and Anodos it seems likely that the women went down and came up the same day, but as the flesh of the pigs was rotten some time must have elapsed. It is therefore conjectured that the flesh was left to rot for a whole year, and that the women on the first day took down the new pigs and brought up last year's pigs.

How long the pigs were left to rot does not affect the general content of the festival. It is of more importance to note that the flesh seems to have been regarded as in some sort the due of the powers of the earth as represented by the guardian snakes. The flesh was wanted by men as a fertility charm, but the snakes it was thought might demand part of it; they were scared away, but to compensate for what they did not get, surrogates made of cereal paste had to be taken down. These paste surrogates were in the form of things specially fertile. It is not quite clear whether the pine-cones etc. or only the pigs were let down at the Thesmophoria as well as the Arrephoria, but as the scholiast is contending for the close analogy of both festivals this seems probable. It does not indeed much matter what the exact form of the sacra was: all were fertility charms.

The remarks of the scholiast about the double Xtxyos, i.e. the double rationale of the festival, are specially instructive. By his time, and indeed probably long before, educated people had ceased to believe that by burying a fertile animal or a fir-cone in the earth you could induce the earth to be fertile; they had advanced beyond the primitive logic of 'sympathetic magic.' But the Thesmophoria was still carried on by conservative womanhood:

'They keep the Thesmophoria as they always used to do.'

An origin less crude and revolting to common sense is required and promptly supplied by mythology. Kore had been carried down into a cleft by Plouton: therefore in her memory the women went down and came up. Pigs had been swallowed down at the same time: therefore they took pigs with them. Such a mythological rationale was respectable if preposterous. The myth of the rape of Persephone of course really arose from the ritual, not the ritual from the myth. In the back of his mind the scholiast knows that the content of the ritual was 'physical' the object the impulsion of nature. But even after he has given the true content his mind clouds over with modern associations. The festival, he says, is a 'thank-offering' to Demeter. But in the sympathetic magic of the Thesmophoria man attempts direct compulsion, he admits no mediator between himself and nature, and he thanks no god for what no god has done. A thank-offering is later even than a prayer, and prayer as yet is not. To mark the transition from rites of compulsion to rites of supplication and consequent thanksgiving is to read the whole religious history of primitive man.

Some details of the rites of the Thesmophoria remain to be noted. The Thesmophoria, though, thanks to Aristophanes, we know them best at Athens, were widespread throughout Greece. The ceremony of the pigs went on at Potniae in Boeotia. The passage in which Pausanias describes it is most unfortunately corrupt; but he adds one certain detail, that the pigs there used were new-born, sucking pigs (us rwv veovwv).

The Megara

Among nations more savage than the Greeks a real Kore took the place of the Greek sucking pig or rather reinforced it. Among the Khonds, as Mr Andrew Lang has pointed out, pigs and a woman are sacrificed that the land may be fertilized by their blood; the Pawnees of North America, down to the middle of the present century, sacrificed a girl obtained by preference from the alien tribe of the Sioux, but among the Greeks there is no evidence that the pigs were surrogates.

The megara themselves are of some importance; the name still survives in the modern Greek form Megara. Megara appear to have been natural clefts or chasms helped out later by art. As such they were at first the natural places for rites intended to compel the earth; later they became definite sanctuaries of earth divinities. In America, according to Mr Lang's account, Gypsies, Pawnees, and Shawnees bury the sacrifices they make to the Earth Goddess in the earth, in natural crevices or artificial crypts. In the sanctuary of Demeter, at Gnidos, Sir Charles Newton found a crypt which had originally been circular and later had been compressed by earthquake. Among the contents were bones of pigs and other animals, and the marble pigs which now stand near the Demeter of Cnidos in the British Museum. It is of importance to note that Porphyry, in his Gave of the Nymphs, says, that for the Olympian gods are set up temples and images and altars, for the chthonic gods and heroes hearths for those below the earth there are trenches and megara. Philostratos, in his Life of Apollonius, says, 'The chthonic gods welcome trenches and ceremonies done in the hollow earth.'

Eustathius says that megara are 'underground dwellings of the two goddesses,' i.e. Demeter and Persephone, and he adds that 'Aelian says the word is fjayapov not jjueyapov and that it is the place in which the mystical sacred objects are placed. 'Unless this suggestion is adopted the etymology of the word remains obscure. The word itself, meaning at first a cave-dwelling, lived on in the megaron of kings'palaces and the temples of Olympian gods, and the shift of meaning marks the transition from under to upper-world rites.

Art has left us no certain

representation of the Thesmophoria; but in the charming little

vase-painting from a lekythos in the National Museum at Athens, a

woman is represented sacrificing a pig. He is obviously held over

a trench and the three planted torches indicate an underworld

service. In her left hand the woman holds a basket, no doubt

containing sacra. There seems a reminiscence of the rites of the

Thesmophoria, though we cannot say that they are actually

represented.

Art has left us no certain

representation of the Thesmophoria; but in the charming little

vase-painting from a lekythos in the National Museum at Athens, a

woman is represented sacrificing a pig. He is obviously held over

a trench and the three planted torches indicate an underworld

service. In her left hand the woman holds a basket, no doubt

containing sacra. There seems a reminiscence of the rites of the

Thesmophoria, though we cannot say that they are actually

represented.

It is practically certain that the ceremonies of the burying and resurrection of the pigs took place on the first day of the Thesmophoria called variously the Kathodos and the Anodos. It is further probable from the name Kalligeneia, Fairborn, that on the third day took place the strewing of the rotten flesh on the fields. The second, intervening day, also called fjuecrrj, the middle day, was a solemn fast, Nesteia; probably on this day the magical sacra lay upon the altars where the women placed them. The strictness of this fast made it proverbial. On this day prisoners were released, the law courts were closed, the Boule could not meet. Athenaeus mentions the fast when he is discussing different kinds of fish. One of the Cynics comes in and says:

'My friends too are keeping a fast as if this were the middle day of the Thesmophoria since we are feasting like cestreis'; the cestreus being non-carnivorous.

The women fasted sitting on the ground, and hence arose the aetiological myth that Demeter herself, the desolate mother, fasted sitting on the'Smileless Stone.'

The Nesteia

Apollodorus, in recounting the sorrows of Demeter, says: 'and first she sat down on the stone that is called after her "Smileless" by the side of the "Well of Fair Dances." 'The'Well of Fair Dances' has come to light at Eleusis, arid there, too, was found a curious monument which shows how the Eleusinians made the goddess in their own image.

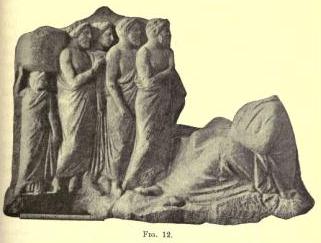

In fig. 12 we have a votive

relief of the usual type, a procession of worshippers bearing

offerings to a seated goddess. But the goddess is not seated

goddess-fashion on a throne; she is the Earth mother, and she

crouches as the fasting women crouched on her own earth.

In fig. 12 we have a votive

relief of the usual type, a procession of worshippers bearing

offerings to a seated goddess. But the goddess is not seated

goddess-fashion on a throne; she is the Earth mother, and she

crouches as the fasting women crouched on her own earth.

A passage in which Plutarch speaks of the women. fasting is of great importance for the understanding of the general gist of the festival. In the discourse on Isis and Osiris he is struck by the general analogy of certain agricultural ceremonies in Egypt and Greece, and makes the following instructive remarks:'How are we to deal with sacrifices of a gloomy, joyless arid melancholy character if it be not well either to omit traditional ceremonies, or to upset our views about the gods or confuse them by preposterous conjectures? And among the Greeks also many analogous things take place about the same time of the year as that in which the Egyptians perform their sacred ceremonies, e.g. at Athens the women fast at the Thesmophoria seated on the ground, and the Boeotians stir up the megara of Achaia, calling that festival grievous (enradrf), inasmuch as Demeter was in grief, on account of the descent of her daughter. And that month about the rising of the Pleiades is the month of sowing which the Egyptians call Athor, and the Athenians Pyanepsion (bean month), and the Boeotians Damatrion. And Theopompos relates that those who dwell towards the West account and call the Winter Kronos, and the Summer Aphrodite, and the Spring Persephone, and from Kronos and Aphrodite all things take their birth.

And the Phrygians think that in the Winter the god is asleep, and that in the Summer he is awake, and they celebrate to him revels which in winter are Goings-to-sleep and in summer Wakings-up. And the Paphlagonians allege that in winter the god is bound down and imprisoned, and in spring aroused and set free again.'

Whatever be the meaning of the difficult Achaia 2 Plutarch has hit upon the truth. Common to all the peoples bordering on the Aegean and, had he known it, to many another primitive race, were ceremonies of which the gist was pantomime, the mimicking of nature's processes, in a word the ritual of sympathetic magic. The women fasted seated on the ground because the earth was desolate; they rose and revelled, they stirred the megara to mimic the impulse of spring. Then when they knew no longer why they did these things they made a goddess their protagonist.

Plutarch has made for himself in his own image his 'ideal' Greek gods, serene, cheerful, beneficent; but he is a close observer of facts, and he sees there are ceremonies 'sacrifices'(Ovaicu) in his late fashion he calls them which are 'mournful,' 'gloomy,' 'smileless.' Who and what are these gods who demand fasting and lamentation? He must either blink the facts of acknowledged authorized ritual this he cannot and will not do, for he is an honest man or he must confuse and confound his conceptions of godhead. Caught on the horns of this dilemma he betakes himself to comparative anthropology and notes analogies among adjacent and more primitive peoples.

Of two other elements in the Thesmophoria we have brief notice from the lexicographers. Hesychius says of the word loyjjia (pursuit), 'a sacrifice at Athens, performed in secret by the women at the Thesmophoria. The same was later called From Suidas 3 we learn that it was also called 'Chalcidian pursuit,' and Suidas of course gives a historical explanation. Only one thing is clear, that the ceremony must have belonged to the general class of 'pursuit' rituals which have already been discussed in relation to the Thargelia.

The remaining ceremony is known to us only from Hesychius. He says,'fyuta (penalty), a sacrifice offered on account of the things done at the Thesmophoria.'

Of the Thesmophoria as celebrated at Eretria we are told two characteristic particulars. Plutarch, in his Greek Questions, asks,

'Why in the Thesmophoria do the Eretrian women cook their meat not by fire but by the sun, and why do they not invoke Kalligeneia?'The solutions suggested by Plutarch for these difficulties are not happy. The use of the sun in place of fire is probably a primitive trait; in Greece to-day it is not difficult to cook a piece of meat to a palatable point on a stone by the rays of the burning midday sun, and in early days the practice was probably common enough; it might easily be retained in an archaic ritual. Kalligeneia also presents no serious difficulty, the word means 'fair-born' or 'fair-birth.' It may be conjectured that the reference was at first to the good crop produced by the rotten pigs' flesh. With the growth of anthropomorphism the 'good crop' would take shape as Kore the 'fair-born, 'daughter of earth. Of such developments more will be said when we discuss the general question of 'the making of a goddess.' A conservative people such as the Eretrians seem to have been would be slow to adopt any such anthropomorphic development.

Another particular as regards the Thesmophoria generally is preserved for us by Aelian in his History of Animals; speaking of the plant Agnos (the Agnus castus), he says,

'In the Thesmophoria the Attic women used to strew it on their couches and it (the Agnos) is accounted hostile to reptiles.'

He goes on to say that the plant was primarily used to keep off snakes, to the attacks of which the women in their temporary booths would be specially exposed. Then as it was an actual preventive of one evil it became a magical purity charm. Hence its name.

The pollution of death, like marriage, was sufficient to exclude the women of the house from keeping the Thesmophoria. Athenaeus tells us that Democritus of Abdera, wearied of his extreme old age, was minded to put an end to himself by refusing all food; but the women of his house implored him to live on till the Thesmophoria was over in order that they might be able to keep the festival; so he obligingly kept himself alive on a pot of honey.

Arrephoria

An important and easily intelligible particular is noted by Isaeus in his oration About the Estate of Pyrrhos. The question comes up,'Was Pyrrhos lawfully married?'I saeus asks. 'If he were married, would he not have been obliged, on behalf of his lawful wife, to feast the women at the Thesmophoria and to perform all the other customary dues in his deme on behalf of his wife, his property being what it was ?'This is one of the passages on which the theory has been based that the Thesmophoria was a rite performed by married women only. It really points the other way; a man when he married by thus obtaining exclusive rights over one woman violated the old matriarchal usages and may have had to make his peace with the community by paying the expenses of the Thesmophoria feast.

Before passing to the consideration of the etymology and precise meaning of the word Thesmophoria, the other women festivals must be briefly noted, i.e. the Arrephoria or Arretophoria, the Skirophoria or Skira, and the Stenia.

The scholiast on Lucian, as we have already seen, expressly notes that the Arretophoria and Skirophoria were of similar content with the Thesmophoria. Clement of Alexandria, a dispassionate witness, confirms this view. 'Do you wish' he asks, 'that I should recount for you the Flower-gatherings of Pherephatta and the basket, and the rape by Aidoneus, and the cleft of the earth, and the swine of Eubouleus, swallowed down with the goddesses, on which account in the Thesmophoria they cast down living swine in the megara. This piece of mythology the women in their festivals celebrate in diverse fashion in the city, dramatizing the rape of Pherephatta in diverse fashion in the Thesmophoria, the Skirophoria, the Arretophoria.'

The Arretophoria or Arrephoria was apparently the Thesmophoria of the unmarried girl. Its particular ritual is fairly well known to us from the account of Pausanias. Immediately after his examination of the temple of Athene Polias on the Athenian Acropolis, Pausanias comes to the temple of Pandrosos, 'who alone of the sisters was blameless in regard to the trust committed to them': he then adds,'what surprised me very much, but is not generally known, I will describe as it takes place. Two maidens dwell not far from the temple of Polias: the Athenians call them Arrephoroi, they are lodged for a time with the goddess, but when the festival comes round they perform the following ceremony by night. They put on their heads the things which the priestess of Athena gives them to carry, but what - it is she gives is known neither to her who gives nor to them who carry. Now there is in the city an enclosure not far from the sanctuary of Aphrodite, called Aphrodite in the Gardens, and there is a natural underground descent through it. Down this way the maidens go. Below they leave their burdens, and getting something else which is wrapt up, they bring it back. These maidens are then discharged and others brought to the Acropolis in their stead.'

From other sources some further details, for the most part insignificant, are known. The girls were of noble family, they were four in number and had to be between the ages of seven and eleven, and were chosen by the Archon Basileus. They wore white robes and gold ornaments. To two of their number was entrusted the task of beginning the weaving of the peplos of Athene. Special cakes called avda-raroi were provided for them, but whether to eat or to carry as sacra does not appear. It is more important to note that the service of the Arrephoroi was not confined to Athene and Pandrosos. There was an Errephoros (sic) to Demeter and Proserpine, and there were Hersephoroi (sic) of 'Earth with the title of Themis' and of 'Eileithyia in Agrae.' Probably any primitive woman goddess could have Arrephoria.

Much is obscure in the account of Pausanias; we do not know what the precinct was to which the maidens went, nor where it was. It is possible that Pausanias confused the later sanctuary of Aphrodite (in the gardens) with the earlier sanctuary of the goddess close to the entrance of the Acropolis. One thing, however, emerges clearly, the main gist of the ceremonial was the carrying of unknown sacra. In this respect we are justified in holding with Clement that the Arrephoria (held in Skirophorion, June July) was a parallel to the Thesmophoria.

It is possible, I think, to go a step further. A rite

frequently throws light on the myth made to explain it.

Occasionally the rite itself is elucidated by the myth to which

it gave birth. The maidens who carried the sacred cista were too

young to know its holy contents, but they might be curious, so a

scare story was invented for their safeguarding, the story of the

disobedient sisters who opened the chest, and in horror at the

great snake they found there, threw themselves headlong from the

Acropolis.

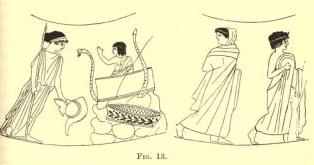

The myth is prettily represented on an amphora in the British Museum, reproduced in fig. 13. The sacred chest stands on rude piled stones that represent the rock of the Acropolis, the child rises up with outstretched hand, Athene looks on in dismay and anger, and the bad sisters hurry away. Erichthonios is here a human child with two great snakes for guardians, but what the sisters really found, what the maidens really carried, was a snake and symbols like a snake. Snake and child to the primitive mind are not far asunder; the Greek peasant of to-day has his child quickly baptized, for till baptized he may at any moment disappear in the form of a snake. The natural form for a human hero to assume is, as will later be seen, a snake.

The little girl-Arrephoroi in ignorance, as became their age, carried the same sacra as the full-grown women in the Thesmophoria. The perfect seemliness and reverence of the rite is shown by the careful precautions taken. When goddesses began to take shape the sacra were regarded, not as mere magical charms, but as offerings as was meet to Ge, to Themis, to Aphrodite, to Eileithyia, but always the carrying was a reverent 'mystery.'

The Skira or Skirophoria presents more difficulties. It was specially closely associated with the Thesmophoria of which it may have formed part. The chorus in the Thesmophoriazusae of Aristophanes says,

'If any of us bear a good citizen to the state, a taxiarch or strategos, she ought to be rewarded by some honourable office, the presidency ought to be given her at the Stenia and the Skira and at any other of the feasts which we (women) celebrate.'

The scholiast remarks, 'both were feasts of women; the Stenia took place before the two days of the Thesmophoria on the 7th of Pyanepsion, and the Skira, some say, are the sacred rites that took place on this feast (i.e. the Thesmophoria) to Demeter and Kore. But others say that sacrifice was made to Athene. On the other hand in an inscription, usually a most trustworthy authority, the two ceremonies are noted as separate though apparently analogous. In the inscription in question 3 which is of the 4th century B.C., certain regulations are enforced'when the feast of the Thesmophoria takes place, and at the Plerosia, and at the Kalamaia and the Skira, and if there is any other day on which the women congregate by ancestral usage.'

The ancients themselves had raised the question whether the Skira were sacred to Athene or to Demeter and Kore. This question is not really relevant to our enquiry; Athene, as will be seen later, when the'making of a goddess'is discussed, is simply inabrvaia coprj, the copy, the maiden of Athens, and any festival of any Kore any maiden would early attach itself to her.

More important is the question, What does the word cr/dpa mean? Two solutions are offered. The scholiast on Aristophanes says ricipov means the same as crcidselov, umbrella, and the feast and the month took that name from the fact that at a festival of Demeter and Kore on the 12th of Skirophorion, the priest of Erechtheus carried a white umbrella. A white umbrella is a slender foundation for a festival, but the element of white points in the right direction. The scholiast on the Wasps of Aristophanes commenting on acipov has a happier thought: he says a certain sort of white earth, like gypsum, is called a-Kippds, and Athene is called, Kippap inasmuch as she is daubed with white, from a similarity in the name.

The same notion of white earth appears in the notice of the Etymologicon Magnum on the month Skirophorion,'the name of a month among the Athenians; it is so called from the fact that in it Theseus carried crcipav by which is meant gypsum. For Theseus, coming from the Minotaur, made an Athene of gypsum, and carried it and as he made it in this month it is called Skirophorion.'

But, it will be asked, supposing it be granted that Skira means things made of gypsum and Skirophoria the carrying of such things, what, in the name of common sense, has this to do with a festival of women analogous to the Thesmophoria? Dr A. Mommsen, who first emphasized this etymology, proposes that the white earth was used as manure; this, though possible and ingenious, seems scarcely satisfactory. I would suggest another connection. The scholiast on Lucian has told us that the surrogates deposited in the megara were shaped out of paste made of grain. Is it not possible that the zkipa were such surrogates made of gypsum alone or part gypsum, part flour-paste? That such a mixture was manufactured for food we learn from Pliny. In discussing the preparation of alica from zea (spelt) he says, 'astonishing statement, it is mixed with chalk.' In the case of a coarse sort of zea from Africa, the mixture was made in the proportion of a quarter of gypsum to three of zea. If this suggestion be correct, the Skirophoria is simply a summer Thesmophoria.

If the Skirophoria must, all said, remain conjectural, the gist of the Stenia is clear and was understood by the ancients themselves. Photius remarks on Stenia'a festival at Athens in which the Anodos of Demeter is held to take place. At this festival, according to Euboulos, the women abuse each other by night/ Hesychius explains in like fashion and adds: 'to use bad language, 'to abuse'. According to him they not only abused each other but'made scurrilous jests. Such abuse, we know from Aristophanes, was a regular element of the licence of the Thesmophoria. The Gephyrismoi, the jokes at the bridge, of the Eleusinian Mysteries, will occur to every one: similar in content is the stone-throwing, the Lithobolia of Damia and Auxesia.

It is interesting to note that in the primitive festivals of the Romans, the same scurrility contests appear. At the ancient feast of the Nonae Capratinae, Plutarch tells us,'the women are feasted in the fields in booths made of fig-tree branches, and the servant-maids run about and play; afterwards they come to blows and throw stones at one another. The servant-maids represent here as elsewhere a primitive subject population; they live during the festival in booths as the women did at the Thesmophoria. How precisely this fight and this scurrility serve the end proposed, the promotion of fertility, is not wholly clear, but the throwing of stones, the beating and fighting, all look like the expulsion of evil influences. The scurrilous and sometimes to our modern thinking unseemly gestures savour of sympathetic magic, an intent that comes out clearly in the festival of the Haloa, the discussion of which must be reserved to the end.

Meaning of Thesmophoria

We come next to the all-absorbing question, What is the derivation, the real root-meaning of the term Thesmophoria and the title Thesmophoros? The orthodox explanation of the Thesmophoria is that it was the festival of Demeter Thesmophoros, the law-carrier or law-giver. With Demeter, it is said, came in agriculture, settled life, marriage and the beginnings of civilized law. This is the view held by the scholiast on Theocritus. In commenting on various sacred plants, which promoted chastity, he adds,

'It was a law among the Athenians that they should celebrate the Thesmophoria yearly, and the Thesmophoria is this: women who are virgins and have lived a holy life, on the day of the feast, place certain customary and holy books on their heads, and as though to perform a liturgy they go to Eleusis.'

The scholiast gives himself away by the mention of Eleusis. He confuses the two festivals in instructive fashion, and clearly is reconstructing a ritual out of a cultus epithet. Happily we know from the other and better informed scholiast that the women carried at the Thesmophoria not books but pigs. How then came the pigs and other sacra to be Thesmoi? Dr Frazer proposes a solution. He suggests that the sacra, including the pigs, were called Oevpol, because they were 'the things laid down.' The women were called Thesmophoroi because they carried 'the things laid down'; the goddess took her name from her ministrants.

This interpretation is a great advance on the derivation from Thesmophoros, Law-giver. Thesmophoros is scarcely the natural form for law-giver, which in ordinary Greek appears as Thesmothetes. Moreover the form Thesmophoros must be connected with actual carrying and must also be connected with what we know was carried at the Thesmophoria. But Thesmoi in Greek did certainly mean laws, and Demeter Thesmophoros was in common parlance supposed to be Law-giver. What we want is a derivation that will combine both factors, the notion of law as well as the carrying of pigs.

In the light of Dr Verrall's new explanation of Anthesteria such a derivation may be found. If the Anthesteria be the festival of the charming up, the magical revocation of souls, may not the Thesmophoria be the festival of the carrying of the magical sacra? To regard the Qzapoi, whether they are pigs or laws, as simply 'things laid down,' deriving them from the root 0e, has always seemed to me somewhat frigid. The root Oea is more vivid and has the blood of religion, or rather magic, in its veins. Although it came, when man entered into orderly and civilized relations with his god, to mean'pray,'in earlier days it carried a wider connotation, and meant, I think, to perform any kind of magical ceremonies. Is not fleovcexo alive with magic?

The Curse And The Law

But what has law, sober law, to do with magic? To primitive man, it seems, everything. Magic is for cursing or for blessing, and in primitive codes it would seem there was no commandment without cursing. The curse, the dp a, is of the essence of the law. The breaker of the law is laid under a ban. 'Honour thy father and thy mother' was the first commandment'with promise.' Law in fact began at a time long before the schism of Church and State, or even of Religion and Morality. There was then no such thing as civil'law. Nay more, it began in the dim days when religion itself had not yet emerged from magic, in the days when, without invoking the wrath of a righteous divinity, you could yet 'put a curse' upon a man, bind him to do his duty by magic and spells.

Primitive man, who thought he could constrain the earth to be fertile by burying in it fertile objects, by'sympathetic magic,'was sure to think he could in like fashion compel his fellow. Curse tablets deposited in graves and sanctuaries have come to light in thousands; but before man learnt to write his curse, to spell out the formulary carasco, 'I bind you down,' he had a simpler and more certain plan. In a grave in Attica was found a little lead figure which tells its own tale. It is too ugly for needless reproduction, but it takes us into the very heart of ancient malignant magic. The head of the figure has been wrenched off, both arms are tightly swathed behind the back, and the legs in like fashion; right through the centre of the body has been driven a great nail. Dr Wiinsch, in publishing the figure, compares the story recorded of a certain St Theophilos 'who had his feet and hands bound by magic.' The saint sought relief in vain, till he was told in a dream to go out fishing, and what the fishermen drew up would cure him of his malady. They let down the net and drew up a bronze figure, bound hand and foot and with a nail driven through the hand: they drew out the nail and the saint immediately recovered.

The locus classicus on ancient magic and spells is of course the second Idyll of Theocritus, on Simaetha the magician. Part of her incantation may be quoted here because a poet's insight has divined the strange fierce loveliness that lurks in rites of ignorance and fear, rites stark and desperate and non-moral as the passion that prompts them.

Delphis has forsaken her, and in the moonlight by the sea Simaetha makes ready her magic gear:

'Lo ! Now the barley smoulders in the flame.

Thestylis, wretch ! thy wits are woolgathering!

Am I a laughing-stock to thee, a Shame?

Scatter the grain, I say, the while we sing,

"The bones of Delphis I am scattering."

Bird' , magic Bird, draw the man home to me.

Delphis sore troubled me. I, in my turn,

This laurel against Delphis will I burn.

It crackles loud, and sudden down doth die,

So may the bones of Delphis liquefy.

Wheel, magic Wheel, draw the man home to me.

Next do I burn this wax, God helping me,

So may the heart of Delphis melted be.

This brazen wheel I whirl, so, as before

Restless may he be whirled about my door.

Bird, magic Bird, draw the man home to me.

Next will I burn these husks. Artemis,

Hast power hell's adamant to shatter down

And every stubborn thing. Hark ! Thestylis,

Hecate's hounds are baying up the town,

The goddess at the crossways. Clash the gong.

Lo, now the sea is still. The winds are still.

The ache within my heart is never still.'

The incantations of Simaetha are of course a private rite to an individual end. That the practice of such rites was very frequent long before the decadent days of Theocritus is clear from the fact that Plato in the Laws regards it as just as necessary that his ideal state should make enactments against the man who tries to slay or injure another by magic, as against him who actually does definite physical damage. His discussion of the two kinds of evil-doing is curious and instructive, both as indicating the prevalence of sorcery in his days, and as expressing the rather dubious attitude of his own mind towards such practices.' There are two kinds of poisoning in use among men, the nature of which forbids any clear distinction between them. There is the kind of which we have just now spoken, and which is the injury of one body by another in a natural and normal way, but the other kind injures by sorceries and incantations and magical bindings as they are called caraseo-eo-t, and this class induces the aggressors to injure others as much as is possible, and persuades the sufferers that they more than any other are liable to be damaged by this power of magic. Now it is not easy to know the whole truth about such matters, nor if one knows it is one likely to be able lightly to persuade others. When therefore men secretly suspect each other at the sight of, say, waxen images fixed either at their doors or at the crossways or at the tombs of their parents, it is no good telling them to make light of such things because they know nothing certain about them. 'Evidently Plato is not quite certain as to whether there is something in witchcraft or not: a diviner or a prophet, he goes on to admit, may really know something about these secret arts. Anyhow, he is clear that they are deleterious and should be stamped out if possible, and accordingly, any one who injures another either by magical bindings carasea-ecriv or by magical inductions (firarywyak) or by incantations (etrwsats) or by another form of magic is to die.

The scholiast on the Idyll of Theocritus just quoted knows that one at least of the magical practices of Simaetha was also part of public ritual:

'The goddess at the crossways. Clash the gong.'

Hecate is magically induced, yet her coming is feared. The clash of the bronze gong is apotropaic. The scholiast says that 'they sound the bronze at eclipses of the moon... because it has power to purify and to drive off pollutions. Hence, as Apollodorus states in his treatise Concerning the Gods, bronze was used for all purposes of consecration and purgation.' Apollodorus also stated that 'at Athens, the Hierophant of her who had the title of Kore sounded what was called a gong.' It was also the custom' to beat on a cauldron when the king of the Spartans died.' All the ceremonies noted, relating to eclipses, to Kore and to the death of the Spartan king, are on public occasions, and all are apotropaic, directed against ghosts and sprites. Metal in early days, when it is a novelty, is apt to be magical. The din (fcporos) made by the women when they took down the sacra, whether it was a clapping of hands or of metal, is of the same order. The snakes are feared as hostile demons. These apotropaic rites are not practised against the Olympians, against Zeus and Apollo, but against sprites and ghosts and the divinities of the underworld, against Kore and Hecate. These underworld beings were at first dreaded and exorcised, then as a gentler theology prevailed, men thought better of their gods, and ceased to exorcise them as demons, and erected them into a class of'spiritual beings who preside over curses.' Pollux has a brief notice of such divinities. He says 'those who resolve curses are called "Protectors from evil spirits," Who-send-away, Averters, Loosers, Putters-to-flight; those who impose curses are called gods or goddesses of Vengeance, Gods of Appeal, Exactors.' The many adjectival titles are but so many descriptive names for the ghost that cries for vengeance.

The curse that binds throws light on another element that went to the making of the ancient notion of sacrifice. The formula in cursing was sometimes tcaraad 'I bind down,' but it was also sometimes irapaiwfja 'I give over.' The person cursed or bound down was in some sense a gift or sacrifice to the gods of cursing, the underworld gods: the man stained by blood is 'consecrate' to the Erinyes. In the little sanctuary of Demeter at Cnidos the curse takes even more religious form. He or she dedicates, or offers as a votive offering, and finally we have the familiar dvaoepa of St Paul. Here the services of cursing, the rites of magic and the underworld are half way to the service of 'tendance' the service of the Olympians, and we begin to understand why, in later writers, the pharmakos and other 'purifications' are spoken of as Ovcriai. It is one of those shifts so unhappily common to the religious mind. Man wants to gain his own ends, to gratify his own malign passion, but he would like to kill two birds with one stone, and as the gods are made in his own image, the feat presents no great difficulty. Later as he grows gentler himself, he learns to pray only'good prayers, 'bonas preces'.

The curse (apa) on its religious side developed into the vow and the prayer (evxn), on its social side into the ordinance and ultimately into the regular law; hence the language of early legal formularies still maintains as necessary and integral the sanction of the curse. The formula is not 'do this' or 'do not do that,' but 'cursed be he who does this, or does not do that.'

One instance may be selected, the inscription characteristically known as 'the Dirae of Teos.' The whole is too long to be transcribed, a few lines must suffice.

'Whosoever maketh baneful drugs against the Teans, whether against individuals or the whole people:

''May he perish, both he and his offspring.

'Whosoever hinders corn from being brought into the land of the Teans, either by art or machination, whether by land or sea, and whosoever drives out what has been brought in:

'May he perish, both he and his offspring?

So clause after clause comes the refrain of cursing, like the tolling of a bell, and at last as though they could not have their fill, comes the curse on the magistrate who fails to curse:

'Whosoever of them that hold office doth not make this cursing, what time he presides over the contest at the Anthesteria and the Herakleia and the Dia, let him be bound by an overcurse, and whoever either breaks the stelae on which the cursing is written, or cuts out the letters or makes them illegible:

'Nay Tie perish, both he and his offspring'

It is interesting to find here that the curses were recited at the Anthesteria, a festival of ghosts, and the Herakleia, an obvious hero festival, and at the Dia this last surely a festival of imprecation like the Diasia.

On the strength of these Dirae of Teos, recited at public and primitive festivals, it might not be rash to conjecture that at the Thesmophoria some form of decroi or binding spells was recited as well as carried. This conjecture becomes almost a certainty when we examine an important inscription found near Pergamos and dealing with the regulations for mourning in the city of Gambreion in Mysia. The mourning laws of the ancients bore harder on women than on men, a fact explicable not by the general lugubriousness of women, nor even by their supposed keener sense of convention, but by those early matriarchal conditions in which relationship naturally counted through the mother rather than the father. Women, the law in question enacts, are to wear dark garments; men if they 'did not wish to do this' might relax into white; the period of mourning is longer for women than for men. Next follows the important clause: 'the official who superintends the affairs of women, who has been chosen by the people at the purifications that take place before the Thesmophoria, is to invoke blessings on the men who abide by the law and the women who obey the law that they may happily enjoy the goods they possess, but on the men who do not obey and the women who do not abide therein he is to invoke the contrary, and such women are to be accounted impious, and it is not lawful for them to make any sacrifice to the gods for the space of ten years, and the steward is to write up this law on two stelae and set them up, the one before the doors of the The smophorion, the other before the temple of Artemis Lochia.'

From the Thesmophoriazusae of Aristophanes we learn almost nothing of the ritual of the Thesmophoria, save the fact that the feast was celebrated on the Pnyx: but the fashion in which the woman-herald prays is worth noting; she begins by a real prayer:

'I bid you pray to Gods and Goddesses

That in Olympus and in Pytho dwell

And Delos, and to all the other gods.'

But when she comes to what she really cares about, she breaks into the old habitual curse formularies:

'If any plots against the cause of Woman

Or peace proposes to Euripides

Or to the Medes, or plots a tyranny,

Or if a female slave in her master's ear

Tells tales, or male or female publican

Scants the full measure of our legal pint

Curse him that he may miserably perish,

He and his house, but for the rest of you

Pray that the gods may give you all good things.'

It is of interest to find that not only were official curses written up at the doors of a Thesmophorion, but, at Syracuse, an oath of special sanctity 'the great oath' was taken there. Plutarch tells us that when Callippus was conspiring against his friend Dion, the wife and sister of Dion became suspicious. To allay their suspicions, Callippus offered to give any pledge of his sincerity they might desire. They demanded that he should take 'the great oath'. 'Now the great oath was after this wise. The man who gives this pledge has to go to the temenos of the Thesmophoroi, and after the performance of certain sacred ceremonies, he puts on him the purple robe of the goddess, and taking a burning torch he denies the charge on oath'. It is clear that this 'great oath' was some form of imprecation on the oath-taker, who probably by putting on the robe, dedicated himself in case of perjury to the goddess of the underworld. That the goddess was Kore we know from the fact that Callippus eventually forswore himself in sacrilegious fashion by sacrificing his victim on the feast of the Koreia, 'the feast of the goddess by whom he had sworn.' The curse is the dedication or devotion of others; the oath, like its more concrete form the ordeal, is the dedication of the curser himself.

The connection between primitive law and agriculture seems to have been very close. The name of the earliest laws recorded they are rather precepts than in our sense laws the'Ploughman's Curses'speaks for itself. Some of these Ploughman's Curses are recorded. We are told by one of the 'Writers of Proverbs' that the Bouzyges at Athens, who performs the sacred ploughing, utters many other curses and also curses those who do not share water and fire as a means of subsistence and those who do not show the way to those who have lost it.'Other similar precepts, no doubt sanctioned by similar curses, have come down to us under the name of the Thrice-Plougher Triptolemos, the first lawgiver of the Athenians. He bade men'honour their parents, rejoice the gods with the fruits of the earth and not injure animals. 'Perhaps these were to the Greeks the first commandments 'with promise'.

Such are the primitive precepts that grow up in a com- munity which agriculture has begun to bind together with the ties of civilized life. In the days before curses were graven in stone and perhaps for long after, it was well that when the people were gathered together for sowing or for harvest, these salutary curses should be recited. Amid the decay of so much that is robust and primitive, it is pleasant to remember that in the Commination Service of our own Anglican Church with its string of holy curses annually recited

'They keep the Thesmophoria as they always used to do.'

The Haloa

The consideration of the Haloa has been purposely reserved to the end for this reason. The rites of the Thesmophoria, Skirophoria and Arrephoria are carried on by women only, and when they come to be associated with divinities at all, they are regarded as'sacred to'Demeter and Kore or to analogous women goddesses Ge, Aphrodite, Eileithyia and Athene. Moreover the sacra carried are cereal cakes and nephalia: but the rites of the Haloa, though indeed mainly conducted by women, and sacred in part to Demeter, contain a new element, that of wine, and are therefore in mythological days regarded as'sacred to 'not only Demeter but Dionysos.

On this point an important scholion to Lucian is explicit. The Haloa is 'a feast at Athens containing mysteries of Demeter and Kore and Dionysos on the occasion of the cutting of the vines and the tasting of the wine made from them.' Eustathius states the same fact. 'There is celebrated, according to Pausanias, a feast of Demeter and Dionysos called the Haloa. 'He adds, in explaining the name, that at it they were wont to carry first-fruits from Athens to Eleusis and to sport upon the threshing-floors, and that at the feast there was a procession of Poseidon. At Eleusis, Poseidon was not yet specialized into a sea-god only; he was Phytalmios, god of plants, and as such, it will be later seen his worship was easily affiliated to that of Dionysos.

The affiliation of the worship of the corn-goddess to that of the wine-god is of the first importance. The coming of Dionysos brought a new spiritual impulse to the religion of Greece, an impulse the nature of which will later be considered in full, and it was to this new impulse that the Eleusinian mysteries owed, apart from political considerations which do not concern us, their ultimate dominance. Of these mysteries the Haloa is, I think, the primitive prototype.

As to the primitive gist of the Haloa, there is no shadow of doubt: the name speaks for itself. Harpocration 3 rightly explains the festival, 'the Haloa gets its name, according to Philochorus, from the fact that people hold sports at the threshing-floors, and he says it is celebrated in the month Poseideon.' The sports held were of course incidental to the business of threshing, but it was these sports that constituted the actual festival. To this day the great round threshing-floor that is found in most Greek villages is the scene of the harvest festival. Near it a booth is to this day erected, and in it the performers rest and eat and drink in the intervals of their pantomimic dancing.

The Haloa was celebrated in the month Poseideon (December January), a fact as surprising as it is ultimately significant. What has a threshing festival to do with mid-winter, when all the grain should be safely housed in the barns? Normally, now as in ancient days, the threshing follows as soon as may be after the cutting of the corn; it is threshed and afterwards winnowed in the open threshing-floor, and mid-winter is no time even in Greece for an open-air operation.

The answer is simple. The shift of date is due to Dionysos. The rival festivals of Dionysos were in mid-winter. He possessed himself of the festivals of Demeter, took over her threshing-floor and compelled the anomaly of a winter threshing festival. The latest time that a real threshing festival could take place is Pyanepsion, but by Poseideon it is just possible to have an early Pithoigia and to revel with Dionysos. There could be no clearer witness to the might of the incoming god.

As to the nature of the Haloa we learn two important facts from Demosthenes. It was a festival in which the priestess, not the Hierophant, presented the offerings, a festival under the presidency of women; and these offerings were bloodless, no animal victim (lepelov) was allowed. Demosthenes records how a Hierophant, Archias by name,'was cursed because at the Haloa he offered on the eschara in the court of Eleusis burnt sacrifice of an animal victim brought by the courtezan Sinope.'His condemnation was on a double count, 'it was not lawful on that day to sacrifice an animal victim, and the sacrifice was not his business but that of the priestess.' The epheboi offered bulls at Eleusis, and, it would appear, engaged in some sort of 'bull fight' but this must have been in honour either of Dionysos or of Poseidon who preceded him: the vehicle of both these divinities was the bull. It was the boast of the archon at the Haloa that Demeter had given to men 'gentle foods.'

Our fullest details of the Haloa, as of the Thesmophoria, come to us from the newly discovered scholia on Lucian. From the scholiast's account it is clear that by his day the festival was regarded as connected with Dionysos as much as, or possibly more than, with Demeter. He definitely states that it was instituted in memory of the death of Ikarios after his introduction of the vine into Attica. The women he says celebrated it alone, in order that they might have perfect freedom of speech. The sacred symbols of both sexes were handled, the priestesses secretly whispered into the ears of the women present words that might not be uttered aloud, and the women themselves uttered all manner of what seemed to him unseemly quips and jests. The sacra handled are, it is clear, the same as those of the Thesmophoria: that their use and exhibition were carefully guarded is also clear from the exclusion of the other sex. The climax of the festival, it appears, was a great banquet.'Much wine was set out and the tables were full of all the foods that are yielded by land and sea, save only those that are prohibited in the mysteries, I mean the pomegranate and the apple and domestic fowls, and eggs and red sea-mullet and black-tail and crayfish and shark. The archons prepare the tables and leave the women inside and themselves withdraw and remain outside, making a public statement to the visitors present that the gentle foods were discovered by them (i.e. the people of Eleusis) and by them shared with the rest of mankind. And there are upon the tables cakes shaped like the symbols of sex. And the name Haloa is given to the feast on account of the fruit of Dionysos for the growths of the vine are called Aloai

The materials of the women's feast are interesting. The diet prescribed is of cereals and of fish and possibly fowl, but clearly not of flesh. As such it is characteristic of the old Pelasgian population before the coming of the flesh-eating Achaeans. Moreover a second point of interest it is hedged in with all manner of primitive taboos. The precise reason of the taboo on pomegranates, red mullet and the like, is lost beyond recall, but some of the particular taboos are important because they are strictly paralleled in the Eleusinian mysteries. That the pomegranate was 'taboo' at the Eleusinian mysteries is clear from the aetiological myth in the Homeric hymn to Demeter Hades consents to let Persephone return to the upper air.

'So spake he, and Persephone the prudent up did rise

Glad in her heart and swift to go. But he in crafty wise

Looked round and gave her stealthily a sweet pomegranate seed

To eat, that not for all her days with Her of sable-weed,

Demeter, should she tarry.'

The pomegranate was dead men's food, and once tasted drew Persephone back to the shades. Demeter admits it; she says to Persephone:

'If thou hast tasted food below, thou canst not tarry here,

Below the hollow earth must dwell the third part of the year.'

Porphyry in his treatise on Abstinence from Animal Food, notes the reason and the rigour of the Eleusinian taboos. Demeter, he says, is a goddess of the lower world and they consecrate the cock to her. The word he uses, djiepacrav, really means put under a taboo. We are apt to associate the cock with daylight and his early morning crowing, bub the Greeks for some reason regarded the bird as chthonic. It is a cock, Socrates remembers, that he owes to Asklepios, and Asklepios, it will be seen when we come to the subject of hero-worship, was but a half-deified hero. The cock was laid under a taboo, reserved, and then came to be considered as a sacrifice. Porphyry goes on 'It is because of this that the mystics abstain from barndoor fowls. And at Eleusis public proclamation is made that men must abstain from barndoor fowls, from fish and from beans, and from the pomegranate and from apples, and to touch these defiles as much as to touch a woman in child-birth or a dead body.' The Eleusinian Mysteries were in their enactments the very counterpart of the Haloa.

The Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries are usually treated as if they were a thing by themselves, a ceremony so significant, so august, as to stand apart from the rest of Greek Ritual. If my view be correct, they are primarily but the Eleusinian Haloa: all their ultimate splendour and spiritual as well as social prestige are due to two things, first the fact that Athens for political purposes made them her own, second that at some date we cannot exactly fix, they became affiliated to the mysteries of Dionysos. To Athens the mysteries owe their external magnificence, to Dionysos and Orpheus their deep inward content. The external magnificence, being non-religious, does not concern us; the deep inward content, the hope of immortality and the like are matters of cardinal import, but must stand over till a later chapter, after the incoming of Dionysos has been discussed. For the present what concerns us is, setting aside all vague statements and opinions as to the meaning and spiritual influence attributed by various authors, ancient and modern, to the mysteries, to examine the actual ritual facts of which evidence remains.

Mysteries were by no means confined to the religion of Demeter and Kore. There were mysteries of Hermes, of lasion, of Ino, of Archemoros, of Agraulos, of Hecate. In general mysteries seem to occur more usually in relation to the cult of women divinities, of heroines and earth-goddesses; from the worship of the Olympians in Homer they are markedly absent. In general, by a mystery is meant a rite in which certain sacra are exhibited, which cannot be safely seen by the worshipper till he has undergone certain purifications.

The date of the mysteries at Eleusis is fortunately certain. The ceremonies began on the 13th of Boedromion, i.e. about the end of September, an appropriate date for any harvest festival which was to include the later fruits and notably the grape. Our evidence for this date is an imperial Roman inscription, but this inscription expressly states that its enactments are'according to ancient usage.' 'The people has decided to order the Kosmeter of the Epheboi in accordance with ancient usage to send them to Eleusis on the 13th day of Boedromion, in their customary dress, for the procession that accompanies the sacra, in order that on the 14th they may escort them to the Eleusinion which is at the foot of the Acropolis. Also to order the Kosmeter of the Epheboi to conduct them on the 19th to Eleusis in the same dress, escorting the sacra.' The inscription is of great importance, as it is clear evidence that sacra were part of the regular ritual. What precisely these sacra were we do not know; presumably they were objects like those in use at the Thesmophoria. The going to and fro from Eleusis to Athens is purely political. The sacra were really resident at Eleusis, but Athens liked to think she brought them there. The Epheboi escorted the sacra, but, as was fitting, they were really in charge of, and actually carried by, priestesses.

On the 15th of Boedromion took place the assembling of the candidates for initiation, and the proclamation by the Hierophant in the Stoa Poikile interdicting those whose hands were defiled and those whose lips spoke unintelligible words. Some such interdiction, some 'fencing of the tables' took place in all probability before all mysteries. It is this prorrhesis of course that is parodied by Aristophanes in the Frogs, who actually dares to put his burlesque into the mouth of the Hierophant himself.

The 16th of Boedromion saw the accomplishment of a rite of cardinal importance. The day was called in popular parlance aase fjuva-rai, 'To the sea ye mystics' from the cry that heralded the act of purification. Hesychius in commenting on the expression says 'a certain day of the Mysteries at Athens.' Polyaenus is precise as to the date. He says 'Chabrias won the sea-fight at Naxos on the 16th of Boedromion. He had felt that this was a good day for a battle, because it was one of the days of the Great Mysteries. The same thing happened with Themistocles against the Persians at Salamis. But Themistocles and his troops had the "lacchos" for their call, while Chabrias and his troops had "To the sea ye mystics.'" The victory of Chabrias was won, as we know from Plutarch, at the full moon, and at the full moon the Mysteries were celebrated.

The procession to the sea was called by the somewhat singular name exacrts, 'driving' or 'banishing' and the word is instructive. The procession was not a mere procession, it was a driving out, a banishing. This primary sense seems to lurk in the Greek word zrollzrsz, which in primitive days seems to have mainly meant a conducting out, a sending away of evil. The bathing in the sea was a purification, a conducting out, a banishing of evil, and each man took with him his own pharmakos, a young pig. The exarts, the driving, may have been literally the driving of the pig, which, as the goal was some 6 miles distant, must have been a lengthy and troublesome business. Arrived at the sea, each man bathed with his pig the pig of purification was itself purified. When in the days of Phocion the Athenians were compelled to receive a Macedonian garrison, terrible portents appeared. When the ribbons with which the mystic beds were wound came to be dyed, instead of taking a purple colour they came out of a sallow death-like hue, which was the more remarkable as when it was the ribbons belonging to private persons that were dyed, they came out all right. And more portentous still'when a mystic was bathing his pig in the harbour called Kantharos, a sea-monster ate off the lower part of his body, by which the god made clear beforehand that they would be deprived of the lower parts of the city that lay near the sea, but keep the upper portion.'

The pig of purification was a ritual

element, so important that when Eleusis was permitted (B.C. 350

327) to issue her autonomous coinage it is the pig that she

chooses as the sign and symbol of her mysteries. The bronze coin

in fig. 14 shows the pig standing on the torch: in the exergue an

ivy spray. The pig was the cheapest and commonest of sacrificial

animals, one that each and every citizen could afford. Socrates

in the Republic says

The pig of purification was a ritual

element, so important that when Eleusis was permitted (B.C. 350

327) to issue her autonomous coinage it is the pig that she

chooses as the sign and symbol of her mysteries. The bronze coin

in fig. 14 shows the pig standing on the torch: in the exergue an

ivy spray. The pig was the cheapest and commonest of sacrificial

animals, one that each and every citizen could afford. Socrates

in the Republic says

'if people are to hear shameful and monstrous stories about the gods it should be only rarely and to a select few in a mystery, and they should have to sacrifice not a (mere) pig but some huge and unprocurable victim'

Purification, it is clear, was an essential feature of the mysteries, and this brings us to the consideration of the meaning of the word mystery. The usual derivation of the word is from fjujo, I close the apertures whether of eyes or mouth. The mystes, it is supposed, is the person vowed to secrecy who has not seen and will not speak of the things revealed. As such he is distinguished from the epoptes who has seen, but equally may not speak; the two words indicate successive grades of initiation. It will later be seen that in the Orphic Mysteries the word mystes is applied, without any reference to seeing or not seeing, to a person who has fulfilled the rite of eating the raw flesh of a bull. It will also be seen that in Crete, which is probably the home of the mysteries, the mysteries were open to all, they were not mysterious. The derivation of mystery from fjuvo, though possible, is not satisfactory. I would suggest another and a simple origin.

The ancients themselves were not quite comfortable about the connection with uvw. They knew and felt that mystery, secrecy, was not the main gist of 'a mystery': the essence of it all primarily was purification in order that you might safely eat and handle certain sacra. There was no revelation, no secret to be kept, only a mysterious taboo to be prepared for and finally overcome. It might be a taboo on eating first-fruits, it might be a taboo on handling magical sacra. In the Thesmophoria, the women fast before they touch the sacra; in the Eleusinian mysteries you sacrifice a pig before you offer and partake of the first-fruits. The gist of it all is purification. Clement says significantly, 'Not unreasonably among the Greeks in their mysteries do ceremonies of purification hold the initial place, as with barbarians the bath.' Merely as an insulting conjecture Clement in his irresponsible abusive fashion throws out what I believe to be the real origin of the word mystery. 'I think' he says, 'that these orgies and mysteries of yours ought to be derived, the one from the wrath of Demeter against Zeus, the other from the pollution relating to Dionysos. 'Of course Clement is formally quite incorrect, but he hits on what seems a possible origin of the word mystery, that it is the doing of what relates to a a pollution, it is primarily a ceremony of purification. Lydus makes the same suggestion, 'Mysteries,' he says, 'are from the separating away of a pollution as equivalent to sanctification.'

The bathing with the pig was not the only rite of purification in the mysteries, though it is the one of which we have most definite detail. From the aetiology of the Homeric Hymn to Demeteiy we may conjecture that there were, at least for children, rites of purification by passing through fire, and ceremonies of a mock fight or stone-throwing. All have the same intent and need not here be examined in detail.

The Tokens

On the night of the 19-20th the procession of purified mystics, carrying with them the image of lacchos, left Athens for Eleusis, and after that we have no evidence of the exact order of the various rites of initiation. The exact order is indeed of little importance. Instead we have recorded what is of immeasurably more importance, the precise formularies in which the mystics avowed the rites in which they had taken part, rites which we are bound to suppose constituted the primitive ceremony of initiation.

Before these are examined it is necessary to state definitely what already has been implied, i.e. the fact that at the mysteries there was an offering of first-fruits; the mysteries were in fact the Thargelia of Eleusis. An inscription of the 5th century B.C. found at Eleusis is our best evidence. 'Let the Hierophant and the Torch-bearer command that at the mysteries the Hellenes should offer first-fruits of their crops in accordance with ancestral usage To those who do these things there shall be many good things, both good and abundant crops, whoever of them do not injure the Athenians, nor the city of Athens, nor the two goddesses. 'The order of precedence is amusing and characteristic. Here we have indeed a commandment with promise.

The 'token' or formulary by which the mystic made confession is preserved for us by Clement as follows:'/ fasted, I drank the kykeon, I took from the chest, (having tasted?) I put back into the basket and from the basket into the chest! The statement involves, in the main, two acts besides the preliminary fast, i.e. the drinking of the kykeon and the handling of certain unnamed sacra.

It is significant of the whole attitude of Greek religion that the confession is not a confession of dogma or even faith, but an avowal of ritual acts performed. This is the measure of the gulf between ancient and modern. The Greeks in their greater wisdom saw that uniformity in ritual was desirable and possible; they left a man practically free in the only sphere where freedom is of real importance, i.e. in the matter of thought. So long as you fasted, drank the kykeon, handled the sacra, no one asked what were your opinions or your sentiments in the performance of those acts; you were left to find in every sacrament the only thing you could find what you brought. Our own creed is mainly a Credo, an utterance of dogma, formulated by the few for the many, but it has traces of the more ancient conception of Confiteor, the avowal of ritual acts performed. Credo in unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam is immediately followed by Confiteor unum baptismum, though the instinct of dogma surges up again in the final words in remissionem peccatorum.

The preliminary fast before the eating of sacred things is common to most primitive peoples; it is the simplest negative form of purification: among the more logical savages it is often accompanied by the taking of a powerful emetic. The kykeon requires a word of explanation. The first-fruits at Eleusis were presented in the form of a pelanos. The nature of a pelanos has already been discussed, and the fact noted that the word pelanos was used only of the half-fluid mixture offered to the gods. Its equivalent for mortals was called alphita or sometimes kykeon. Eustathius in commenting on the drink prepared by Hekamede for Nestor, a drink made of barley and cheese and pale honey and onion and Pramnian wine, says that the word kykeon meant something between meat and drink, but inclining to be like a sort of soup that you could sup. Such a drink it was that in the Homeric Hymn Metaneira prepared for Demeter, only with no wine, for Demeter, as an underworld goddess 'might not drink red wine': and such a wineless drink, made in all probability from the pelanos and only differing from it in name, was set before the mystae.

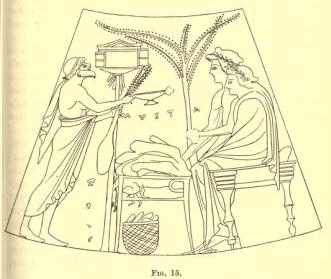

Some ceremony like the drinking of

the kykeon is represented in the vase-painting in fig. 15. Two

worshippers, a man and a woman, are seated side by side; before

them a table piled with food, beneath it a basket of loaves. They

are inscribed Mystae (Mvora). A priest

holding in the left hand twigs and standing by a little shrine,

offers to them a cylix containing some form of drink. The

presence of the little shrine has made some commentators see in

the priest an itinerant quack priest (dyvptrjs), but it is quite possible that shrines

of this kind containing sacra were carried at the Eleusinian

mysteries. Anyhow the scene depicted is analogous.

Some ceremony like the drinking of

the kykeon is represented in the vase-painting in fig. 15. Two

worshippers, a man and a woman, are seated side by side; before

them a table piled with food, beneath it a basket of loaves. They

are inscribed Mystae (Mvora). A priest

holding in the left hand twigs and standing by a little shrine,

offers to them a cylix containing some form of drink. The

presence of the little shrine has made some commentators see in

the priest an itinerant quack priest (dyvptrjs), but it is quite possible that shrines

of this kind containing sacra were carried at the Eleusinian

mysteries. Anyhow the scene depicted is analogous.

The Sacra

Of the actual sacra which the initiated had to take from the chest, place in the basket, and replace in the chest, we know nothing. The sacra of the Thesmophoria are known, those of the Dionysiac mysteries were of trivial character, a ball, a mirror, a cone, and the like: there is no reason to suppose that the sacra of the Eleusinian mysteries were of any greater intrinsic significance.

Clement in a passage preceding that already quoted gives the Eleusinian'tokens with slightly different wording and with two additional clauses: he says 'the symbols of this initiation are,

I ate from the timbrel, I drank from the cymbal, I carried the kernos, I passed beneath the pastos.'

The scholiast on Plato's Gorgias makes a similar statement. He says

'at the lesser mysteries many disgraceful things were done, and these words were said by those who were being initiated: I ate from the timbrel, I drank from the cymbal, I carried the kernos';

He further adds by way of explanation'the kernos is the liknon or ptuon,' i.e. it is some form of winnowing fan.

There has been much and, I think, needless controversy as to whether this form of the tokens belongs to the mysteries at Eleusis or not. From the words that precede Clement's statement, a mention of Attis, Kybele and the Korybants, it is quite clear that he has in his mind the mysteries of the Great Mother of Asia Minor, but from his mentioning Demeter also, it is also clear that he does not exactly distinguish between the two. The mention of the'tokens'by the scholiast on Plato is expressly made with reference to the Lesser Mysteries, and these, it will later be seen, are related especially to Kore and Dionysos. The whole confusion rests on the simple mythological fact that Demeter and Cybele were but local forms of the Great Mother worshipped under diverse names all over Greece. Wherever she was worshipped she had mysteries, the timbrel and the cymbal came to be characteristic of the wilder Asiatic Mother, but the Mother at Eleusis also clashed the brazen cymbals. In her 'tokens' however her mystics ate from the cista and the basket, but the distinction is a slight one.

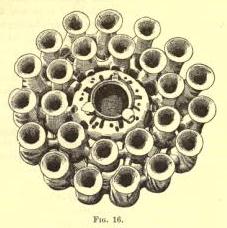

The KernophoriaThe question of the kernos is of some interest. The scholiast states that the kernos was a winnowing fan, and the winnowing fan we shall later see was, at least in Alexandrine days, used in the mysteries of Eleusis. It was a simple agricultural instrument taken over and mysticized by the religion of Dionysos. From Athenaeus however we learn of another kind of kernos. In his discussion of the various kinds of cups and their uses he says:'Kernos, a vessel made of earthenware, having in it many little cups fastened to it, in which are white poppies, wheat, barley, pulse, vetch, ochroi, lentils; and he who carries it after the fashion of the carrier of the liknon, tastes of these things, as Ammonius relates in his third book On Altars and Sacrifices.' A second and rather fuller notice of the kernos is given by Athenaeus a little later in discussing the kotylos.' Polemon in his treatise "On the Dian Fleece " says, " And after this he performs the rite and takes it from the chamber and distributes it to those who have borne the kernos aloft."' Then follows an amplified list of the contents of the kernos. The additions are italicized: 'sage, white poppies, wheat, barley, pulse, vetch, ochroi, lentils, beans, spelt, oats, a cake, honey, oil, wine, milk, sheep's wool unwashed.'

The list of the traycaptria, the offering of all fruits and natural products, is in some respects a primitive one: the unwashed wool reminds us of the simple offering made by Pausanias at the cave of Demeter at Phigalia; but there are late additions, the manufactured olive oil and wine. Demeter in early days would assuredly never have accepted wine. The kernos, like the offerings it contained, is comparatively late and complex. Vessels exactly corresponding to the description given by Athenaeus have been found in considerable numbers in the precinct at Eleusis, both vessels meant for use and others obviously votive. In the accounts of the officials at Eleusis for the year 408 B.C. there is mention of a vessel called cepxvos, which in all probability is identical with the kernos of Athenaeus. The shape and purport of the vessel are clearly seen in the very perfect specimen in fig. 16.

Such a vessel might well be called

a separator; each of the little kotyliskoi attached would contain

a sample of the various grains and products. It is easy to see

how the scholiast might explain it as a liknon. The liknon was an

implement for winnowing, separating grain from chaff, the kernos

a vessel in which various sorts of grain could be kept separate.

The Kernophoria was nothing but a late and elaborate form of the