A Peep at the Pixies, or Legends of the West

By Anna Eliza Bray

The Belfry Rock; or, The Pixies' Revenge

ON the borders of Dartmoor, in days of yore, there lived a rich old farmer, in one of the fields near whose house, stood a very curious object, a large moor-stone rock, shaped by nature so much like an ancient Gothic church with a tower, that it was known among the country people for miles round by the name of" The Pixies' Church."

THE PIXIES' REVENGE

It was also encompassed by a Pixy ring; and many old persons declared that ever since they could remember, if you placed your ear close to the rock on a Sunday, you could hear a small tinkling sound, resembling the church bells at Tavistock, and usually at the very time they were ringing to warn the good people of that town for the morning service. It was said, likewise, that the same sound could be heard when the bells of Tavistock chimed, as they always did at four, and eight, and twelve o'clock. One old woman protested that so long ago as when her great grand-father, who was fond of music, was a little boy, he was frequently seen to place his ear against the rock to listen, as he thought, to the Pixies' ringing; and although he had never been at Tavistock, he thus learned the tune of the 100th Psalm which the chimes there used to play daily.

He declared that he heard the Pixy music best when he put his head in a hole in the portion of the rock which was called the belfry tower. When he grew up to be a man he learned to play on the bass viol with which he led the choir of a neighbouring village; and it was always noticed that there was no tune he played with so much spirit as the 100th Psalm, which he had so often heard at the belfry rock.

"And, as sure as you are alive," said the ancient dame, who repeated this story round many a Christmas fire, "the Pixies love bell-ringing, and go to church o' Sundays."

Well, it so happened, that the farmer wanted stones, to make the wall of some additional buildings to his house; and the "Church-rock" being near, he bethought him how much time, trouble, and expense would be saved, by making the granite of the tower supply his need. But when he made known his intentions to his workmen, they stood aghast with dread. One and all did they declare that they would have no hand in the matter. What! dare to strike off even a bit of a stone from the Pixies' church! they would not do such a thing for the weight of the whole rock in gold. It would be sure to bring down the vengeance of the whole band of Pixies upon them; they had scarcely ever ploughed up or disturbed a Pixy ring, but they were sure to suffer for it, by pains in the bones, cramps, and rheumatics; and as to touching the rock, they dared not do it for their lives.

Finding that be could do nothing with his men, the old farmer, being as stout and sturdy as he was obstinate, determined to work himself, and to make his sons help him. And so, in good earnest, they began the work of destruction; and block after block was removed from the musical tower. But this deed of mischief and spoliation was not done without some marks of anger, and even of suffering, from the invisible little beings thus disturbed in their favourite haunts. Low and piercing shrieks were constantly heard from the rock; and the masons (those who had refused to help to take the stones from such a quarry), whilst engaged in raising the building, were terribly troubled with cramps, and felt every night, when they lay down to rest, as if pins were running into their flesh, so that they were heartily glad when the work was completed.

But now began the Pixies' revenge upon the man who had been at the head of thus offending them. One morning, when the old farmer came down into the kitchen, he found a heap of ashes on the hearth, within the ample space of the chimney. It looked absolutely as if there had been a bonfire made of a whole rick of wood; and, on going into the wood-yard, he found the better part of his rick, more especially all the great logs that he had been saving up for the Christmas week, gone. He next proceeded to the cow-house. It was in the depth of Winter; and there he was struck with horror on beholding his finest, fattest, and most favourite cow, the very queen of cows for grace and beauty, standing shivering and shaking, reduced to a living skeleton; her eyes staring out of her head, and her bones scarcely covered with skin. What a sight! "The Pixies have pity on me," exclaimed the old man; "for truly do I fear this is their work." On the two following mornings it was just the same thing--a heap of ashes on the hearth, and now a fat ox reduced to a living skeleton! At length the old farmer plucked up courage, and determined that, on the next night, he would watch and find out the mystery.

He effected his purpose by concealing himself in a hollow place in the wall of the kitchen, called the smuggler's hole; for, if fame did him no wrong, the old fellow was said, now and then, to do business in an unlawful way. Well, there was he concealed. Exactly as the clock struck twelve, he heard a noise something like the humming of bees at the kitchen door; and directly after perceived a little creature, very diminutive, but shaped like a human being, come forth through the key-hole.

Immediately Friskey (for such, it seemed, was the name of this Pixy) took down from a nail, where it hung near the door, the ponderous key (the weight of which was almost too much for him), and with it, at length, the young gentleman managed to unlock the door.

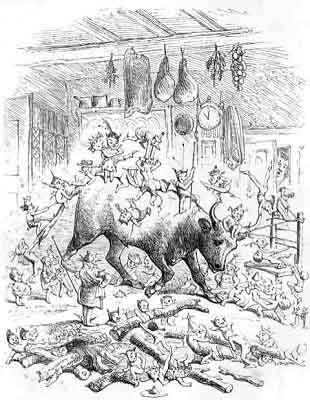

To his utter amazement, what should the old farmer next see, but one of his fine fat oxen driven in by myriads of little creatures; some sitting on the animal's back, others pulling him by the ears, a few swinging on his tail, and a couple of rogues, one perched on the tip of either horn, amusing themselves by turning about, in their antics, like the weather-cocks on the tops of the pinnacles of Tavistock church.

This Pixy progeny, though numerous, were by no means very handsome. The tallest of them was (said the old gossip, the narrator of this most wonderful history) not higher than her kitchen candle-stick; that was, about six inches from crown to toe; and the miniature Pixies, or dwarfs among them, were scarcely half so tall. They looked, added this observing old dame, for all the world like little stoats, standing on their hinder legs. They had fierce black eyes, large mouths, and red fiery tongues, flashing and shining like pen-knives, as they thrust them out.

This band of little imps, who seemed to be of no very gentle or amiable nature, soon drove the poor ox near the kitchen chimney. Then, urchins though they were, they threw him down in a minute; all hands set to work and fairly skinned him, being careful in so doing not to break the hide. Whilst this operation was going on, another party of these diminutive monsters (if so they may be called) busied themselves in bringing in great logs of wood. It was truly wonderful to see such little creatures capable, by their numbers, of removing such loads. The logs were disposed upon the hearth. One of the Pixies then breathed upon them, and immediately they kindled into a flame.

Friskey next clapped his tiny hands, and forthwith three obedient Pixies appeared, each mounted and sitting between the prongs of a pitchfork turned upwards, and so they glided onward towards the fire. The pitchforks stopped of themselves, and then the urchins dismounted; and one putting his fork into the nose of the poor ox, whilst the other did the same to his rump, and the third poked at his side, they had him up in a trice, and contrived to suspend him ready for roasting before the fire. And then they all set to and whirled and turned him backwards and forwards and round about like so many mad turnspits, and basted him with the cook's ladle and with all the butter and cream that they could steal from the dairy; for Pixies are very good cooks, and know that meat is never delicate or tender unless basted with care. The roasting was soon finished; for a fire kindled by such means is strong, swift, and subtle in its operations.

And then, exactly while the old farmer in his hiding hole could count seven, three times was the ox lifted up and three times again let down, before it was transferred to the large kitchen table. This done, one little wretch, far more ugly than all the rest, with something bright and sparkling about his brows (the form of which the farmer could not exactly make out), stamped with his tiny feet, and bade the whole band to the feast. In another moment, out flew a thousand little knives, each in shape resembling a cutlass, and each Pixy fell to "tooth and nail," on the good cheer, cutting and carving and helping himself. They all seemed highly to enjoy their supper, and chatted and talked as fast as they ate in a sort of squeak very like the squeak of mice in a corner. These little wretches contrived in a few minutes, to devour fat and lean, and every part of the ox except the brain, the eyes, and bones and sinews. The bones, however, were picked quite clean, and looked to the wondering farmer, to be as white as drifted snow. They were then cast under the table.

But O how the old man did tremble and quake with fear when he saw that one of the small bones of the beast had fallen near the entrance of the hole in the wall, where he lay concealed. He had, however, courage and presence of mind sufficient to stretch out his hand and catch up this small bone. He then shut to the little softly-sliding panel that formed a sort of door to the entrance of his secret retreat; for he was so overcome with terror that he could not bear any longer to behold such a scene of mischief, and could hardly suppress his groans for the loss of his favourite ox. However, he could not forbear, now and then, taking a peep at what was still going on.

Presently he perceived the Pixy company set to dancing and capering like mad things; and this they did in a ring, holding each other by the hand, and making a humming noise like a tune (though a very wild and strange one) which was only interrupted by the mouselike squeak and a sort of chuckling, for that was their manner of mirth and laughter. After they were pretty well tired with their sports, the little Pixy who looked more old and ugly than all the rest, gave a sharp shrill cry, and immediately all the party began to collect the scattered bones, and to put them together with wonderful ease and precision, fastening them with ligatures and sinews. The little creatures, however, in building up the ox, missed the small bone, and appeared greatly alarmed lest it should bring upon them the anger of their king. But after consulting together, they seemed to form a plan to conceal it from him pretty readily.

They next laid out the skeleton of the ox, as clean and as perfect as if they had been doing it to oblige any Surgeon Hunter, or Professor Owen, for their schools of anatomy. They then took the horns and the hoofs (which they removed before supper) with very great care; and, lastly, drew the skin over the bones with admirable dexterity. It went on without pulling, for there was no flesh left to create the slightest difficulty.

This finished, once more all joined hands, made a ring, and danced three several times round the ox; and, lastly, all united in uttering one small shrill piercing cry. This was repeated thrice more, "and thrice again," as the witches say in the play of Macbeth, "to make up nine." Several of them then climbed upon the creature's back, as nimbly as young cats, and placed themselves about the head, and seemed to breathe and utter sounds in the mouth and ears.

All these rites being accomplished, the leader among the Pixies took several pieces of birch from a broom in the kitchen, and, making one after his own fashion, proceeded to rub down the ox, from the tip of his nose to the end of his tail. Whereupon the animal began slowly to re-animate. First he opened one eye, and then another; shook his ears, and rolled out his tongue; and then he gave such a sudden whisk with his tail, that he tumbled off from it a dozen or two of Pixies who were amusing themselves by hanging upon it, as ship-boys do upon a rope; and, lastly, he gave such a bellow, that it even startled the old farmer in his hole. Their sport for the night being accomplished, and fearing the ox, with his bellowing, would disturb the house, the Pixy tribe proceeded to drive the poor beast towards the door; but they could. not do even this like other creatures, for they did it by teazing and pinching him in a very wanton manner. And then it was found, that, for want of the small missing bone, the animal limped terribly, and went lame on one leg. They all, however, got out, much in the same way that they got in. Friskey staid behind, to lock the door and hang up the key, and then bobbed through the key-hole after the others.

And now, my young friends, you want to know what became of the old man; and I'll tell you. As soon as all was quiet, he crept out of his smuggling-hole, and went to bed, terribly frightened; but could not get a wink of sleep all the night for thinking of the Pixies. As soon as it was day, he got up, and went straight to the ox-house; and there he found his poor skeleton beast, halting on one leg. Now, there was a strange kind of old woman lived near him, who was called old Joan, the witch; but, though he consulted her upon the case, it seemed that she could do nothing for him, but rather inclined to favour the Pixies; very probably they were her personal friends. However, being hard pressed to give advice, she told the farmer to go to a conjuror, known by the name of the White Wizard of Exeter; a little, short, funny old man, who was very formidable when he chose to use his power over witches and pixies, and little devils of all kinds and degrees.

The farmer did go to Exeter, and related to the White Wizard all that had happened. How he took down the tower of the Pixy church, and broke it up for stones for his building, and every thing which had befallen him; and all that he had both seen and heard with his own eyes and ears. The White Wizard thought the affair a very bad one; but not altogether hopeless. He counselled the farmer to go home, pull down his new building, carry back all the stones to where he had taken them from, put them down on the same spot, but not to attempt to do anything more to them. Although grieved, and vexed to think he must be at so great a loss as all this implied, yet the old man obeyed. Great was his surprise when, on going out the next morning, he found the Pixy church and tower built up again, exactly as it was before, and not a stone out of its place.

But, alas! after he had first disturbed the Pixy tower, nothing went well with him; for, though it had been built up again, he moped about in low spirits, which he could not overcome, and got as lean and as miserable as one of his poor skeleton oxen. All this the old farmer related to the parson of the parish, and said that he made the confession on purpose to ease his conscience before he died, which he did soon after.

Now this very sad and disastrous tale was, for a long period, the subject of narrative at Christmas and Michaelmas eves, over the hot pies and the white ale, also made hot, with the addition of spice, eggs, and sugar, in all the villages bordering on Dartmoor. It was related as a warning both to young and old, never to meddle with, or to destroy, any Pixy rocks, houses or buildings, or rings of any kind or description, as these little Pixy beings, though sometimes of service where they take a fancy, are, nevertheless, spiteful and revengeful in their nature, and will requite an offence with tenfold injury, be it what it may.

NOTES TO "THE BELFRY ROCK; OR, THE PIXIES' REVENGE."

The Belfry Rock, commonly called the Church Rock, on Dartmoor, on account of its resemblance to a church. I know not if it is still in being, as great havoc of late years has taken place on the moor; many rocks have been blasted with gunpowder, broken up for the roads, and otherwise destroyed. But the Church Rock was long remembered; and many old persons have declared, that they could recollect the time when, if you placed your ear close to it on a Sunday, you could hear a low tinkling sound like the bells of Tavistock Church, and always at the time of warning for service; and they also said, that the chimes, at the regular hours of the day for chiming, could be so heard at the rock. All this was duly ascribed to the Pixies, who, it was believed, loved bell-ringing, and went to church. Hence the rock in question received the name of the Pixies' Church. It is not at all improbable, that, when the wind was in the right quarter, the sounds heard at the rock were the faint echoes of the Tavistock bells.

For a knowledge of the local tradition, on which the tale of the Belfry Rock is founded, I am indebted to Mr. Merrifield, a barrister, and a man of talent in more things than the law, a native of the town of Tavistock, and the husband of a lady well known for her literary merits.

THE END.