A Peep at the Pixies, or Legends of the West

By Anna Eliza Bray

The Lady of the Silver Bell

I HAVE already told you, my young friends, a story in connexion with Tintagel; and now purpose to relate to you another; the events of which occurred in the same place, though at a somewhat more recent period, when a certain Baron was Lord of that ancient castle, and lived there with much splendour and state.

THE LADY OF THE SILVER BELL

This great Baron had only one child, a daughter, who was as fair as a lily, and when she turned her head, her neck moved with the grace and beauty of the swan; at least in such terms of praise was she described by the old harper in his songs, as, every feast day, he gladdened the halls of Tintagel with the thrilling notes and full chords of his harp. She was commonly called Serena, on account of her generally placid demeanour; and as her father was very fond of seeing her dressed in white and silver, because he thought she looked prettiest when so attired; she was not unfrequently called the silver lady.

Her nurse declared, that, when the child was in the cradle, she had been blessed by the Pixies; and it was that which made her look so fair and beautiful, and caused her to be so lucky in all she took in hand. "But woe be to her," would the old gossip add, when she said this, "woe be to her, if my lady Serena should offend the Pixies; for, like us mortal sinners, they will often most hate where they have most loved; and especially if they be jealous or offended."

Although her mother died when she was an infant, Serena received a very good education; for her nurse taught her so well how to work with the needle, that all the finest tapestry hangings in the castle were said to be in part wrought by her. The old minstrel instructed her in playing the harp; and she often sang to it many a Cornish ballad or ditty; and above all, Father Hilary had well disciplined her in her religious duties. She had given him a promise that she would never be absent from church at the ringing of the vesper bell; never, she said, unless prevented by sickness, would she be tempted to stay away when that bell was calling her to prayers, let what would happen. She gave this promise to Father Hilary so seriously, that he, as well as the nurse, assured her, if ever she broke it, the good spirits who were her guardians would fly away from her, and leave her exposed to injury from the bad ones. Serena said, in reply, "No music was so sweet to her ears as the vesper bell."

But though the Baron's daughter had so many good qualities, she had, I am sorry to say, some very great faults. She was excessively vain and fond of dress, and at times sadly whimsical and capricious. When she grew up to womanhood, her father wanted her to marry some one of the gallant young knights who came to the castle; but such was her vanity, she deemed none good enough. Among them was a very gentle and amiable youth, who was so comely and graceful, that every body said how happy she would be as his wife. And the old nurse declared that, from the dreams she had about him, and his having first been brought to the sight of her young lady, by the sounds of sweet music, which seemed to float in the air and to guide his steps to Tintagel, at the very moment Serena was issuing from the castle gates, she was quite sure it was the Pixies, and nothing but the Pixies, who thus led him along to give him, as a very great favour, to Serena for a husband. Serena at first appeared to like him well, and he came very often to the castle; but at length she changed her mind, tossed her head, disappointed him, and said that neither he nor any other of her father's friends, were handsome enough to please her; and in the caprice of her mood, she declared that she would never marry unless she could meet with a young prince who was handsomer, and dressed better, and played on the lute sweeter, than any one she had ever yet seen or heard.

Her old nurse sighed as she listened to all this, and said, "O my dear young lady, do not talk so! Beware what you say. You have behaved ill and whimsically to that poor young gentleman, whom every body loved; he was so good and kind. Depend upon it, the Pixies will take their revenge one of these days for the manner in which you treated him, or I don't know them or their doings. The only way to save yourselves from their spite, is to be very penitent for your fault; and to be mindful of your promise to Father Hilary. For if you go wrong again, the evil spirits may take advantage of your folly, sadly to mislead and deceive you; and I should break my old heart if any harm happened to my dear young lady, whom I have nursed in these arms from the hour she was born."

Serena paid little heed to this good advice, but soon after indulged in such extravagance and gaiety, in so much dancing and singing, that Father Hilary interfered, and strictly enjoined her, as a sort of penance for spending her time so idly, to repair alone every day for one month to come, to a little chapel which stood near St. Nathan's Kieve, and to be sure, according to her promise, always to enter within its doors before the ringing of the vesper bell had ceased.

St. Nathan's Kieve was three miles and a half from Tintagel, a long and weary way, and over a difficult road; and though Serena now and then went on horseback, yet as walking far through such rough paths was a sort of penance, to please old Hilary, who was rather cross-grained and crabbed, and had no pity for her poor feet, she more frequently walked than rode.

On the day of which I am about to speak, Serena set out early on foot, as she was determined not to be hurried in her walk. She was dressed in a long grey cloak, and upon her head she wore a little grey cap made of cloth; a scallop shell was seen in front of it, to show that she was going on a sort of pilgrimage. As she put on her cloak, her nurse gave her a caution to let nothing stay her by the way, but to go on straight to the chapel, to enter before the bell had ceased ringing, come straight home, for, said the good old woman, "those who allow anything they meet with to delay them when they are going to prayers, are sure to lay themselves open to the power of those wicked spirits that I told you of before, they are sure to be punished for it."

Serena took leave of her aged counsellor with repeated promises to mind what she said. She passed the castle gates in a somewhat hurried manner, for fear .of meeting Father Hilary, as she liked not to be lectured by him on her way. With a quick step did she also pass the village of Trevenna. As she began to ascend the high ground beyond it, she slackened her pace, and looked back upon Tintagel, which now opened with all its grandeur of castle and cliff upon the view. She had never so attentively observed it as on this day; and, she could not tell why, but she then gazed upon it with a melancholy interest.

It was indeed a fine sight, and whilst the walls and towers of her father's ancient dwelling were lit up with a flood of light, the rock called Long Island, was in complete gloom from the overshadowing clouds. This rock wild, lofty, broken, close in shore, though surrounded by the waves, was said to be peopled, and especially after nightfall, by sea-gulls and spirits. Serena now, therefore, looked upon it in its sombre hue with a secret sense of dread. Nor was it without a shudder that as she turned to continue her walk she saw a solitary magpie pacing up and down on the very road she had to cross. She did not like the evil sign, and she thought that she would take a shorter way, and find out that the country people sometimes took in going to chapel.

But Serena was soon bewildered, and at length got into a strange rough road over a field that descended as precipitously as the roof of a house to the bottom of a ravine, beautifully clothed with wood. She could hear the running of water, and soon came in sight of a stream that ran rapidly under a vast number of trees. This she crossed and still advanced. She now perceived some overhanging rocks, and on the hill above these stood the little chapel. She had not advanced very far, when she heard the vesper bell. Mindful of her promise she determined to retrace her steps as speedily as possible, and no longer linger, though in so lovely a scene.

But at that very moment she heard strains of the most enchanting music. Nothing earthly seemed to mingle with those sounds. "O Serena! Serena, quickly turn, hark to the vesper bell." She fancied that a voice above the rocks spoke these words. But, alas! she neglected the friendly warning. She looked this way, that way, up the ravine, among the trees, and could see no one; whilst every step she advanced, the music of the unseen musician appeared to move on before her. "I will but tarry a few minutes to see who it is plays thus sweetly, and where the sounds come from," said Serena, "I shall yet reach the chapel yonder, before the bell has done ringing."

She now continued descending the difficult and winding path, which turned sharply round among rocks that peered above her head in the most fantastic forms; the roots of the trees clung to them in all directions. So narrow had the path become between the rocks and the stream, that it scarcely afforded room to pass; and as the stones were slippery with moss and damp, and here and there the arm of a tree crossed close above the head, to pass along was both precarious and dangerous.

Again did Serena listen, and still could she hear, even above the sounds of the rushing waters, the vesper-bell. She now in good earnest determined to turn back. But at that moment, such a strain of sweetness arose; it caught her ear, and she became once more fixed by the spell of such enchanting harmony. Alas! it was of more power than the call of duty over her wavering mind.

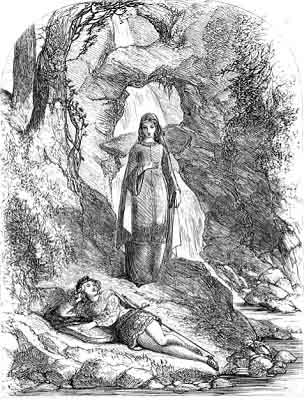

The music now seemed to come from the opposite side of the stream; and so much was her curiosity excited, that she took the resolution to try to cross it, and to find out the unseen minstrel. She looked round and perceived some large loose stones, which served, though not without risk, for stepping-stones. Serena was light of foot and very active; and so by marking well, where to venture, and springing from rock to rock, she managed to get over the stream. Again did she enter on a narrow path, and followed it for a few yards, when, on a sudden turn, she came in sight of the loveliest waterfall that she had ever beheld.

It was situated at the extremity of a recess among the wildest rocks. These formed so complete an inclosure, that it was only in front facing the fall that a view of it could be gained. The cascade itself was not lofty, not above fifty or sixty feet in height; it was its form and accompaniments which rendered it of such surpassing loveliness. A few yards distant from the fall, there stood fronting it some rocks, which half way up had the appearance of a natural arch; and through this opening the foaming waters were seen leaping and dashing over the rocks, with the most beautiful effect. Thence they rushed on in the wildest tumult over vast masses of granite, which lay in the bed of the stream as if to impede its course. Here and there, occasioned by the hollows beneath, might be found a calm deep pool, undisturbed by the impetuosity of the flood.

Serena stopped, delighted with the beauty of the scene. "This is the sweetest ravine in the world," she said; "such a beautiful waterfall, and the rocks so wild and broken; and all shut in to keep it, as it were, from the approach of common mortals. Surely this must be the very place in which my nurse tells me, that Merlin of old, the great magician, in the days of Prince Arthur, used to work his spells; where the Pixies make their favourite haunt, and where they are now most powerful, and, therefore, most to be feared. But that must be false; for nothing to be feared can ever come into such a charming scene as this. But I must not linger; and now to hasten back, for here no vesper-bell can be heard, nor even that delightful music which led me hither, for here the waterfall lets no music but its own meet the ear."

Well might Serena thus admire the scene, for what she so gazed upon were the rocks and fall of Nathan's Kieve.

Serena gave the cascade one last farewell look, and then turned to retrace her steps; but who shall speak her wonder, when, at a short distance from the spot she had quitted, she found it impossible to proceed without the danger of stepping upon a human being, who lay outstretched, with a lute by his side, on the narrow path under the rocks, and so close to the water's edge, that no space was left for her to glide by without disturbing him. She paused a moment; her eyes became as much fascinated by the beautiful appearance of the sleeping figure, as her ears had before been charmed by the mysterious music.

It was a strange place for repose. The sleeper was a young man, of a very good person, and handsome features, with light brown curly hair. His attire was at once rich and elegant. He wore such a cloak and vest as Serena had never before seen; the plumage of the finest birds seemed to have been rifled to give it splendour. And then the cap on his head, and the tiara which was bound around his brows, was so radiant and glittering with jewels, that they looked as if diamonds, and emeralds, and rubies, and sapphires had been clustered together so as to emulate in the manner of their arrangement the colours of the butterfly's wing.

Serena gazed till her admiration of the manly beauty and splendid attire of the youthful sleeper became as great as that which she had felt, a little while before, for the music; and far exceeded her admiration of the beauties of the scene. She thought that, if ever she married, it should be to just such a beautiful youth; and then his dress was so graceful, so rich; and as for his tiara, it would be the prettiest thing imaginable to have just such another to bind around her own dark and flowing hair. She felt quite sure none but a prince could altogether be so charmingly dressed, and so handsome; and he it must be who had produced from that lute such exquisite tones.

Serena was now in no hurry to pass on, but looked about her, and seeing an opening in some rocks near at hand, that were overshadowed by thick and pendant boughs, she determined to conceal herself and to survey more at her leisure the noble features and the splendid adornments of the. sleeper; hoping that, when he awoke, he would again touch the strings of his lute. The vesper bell was forgotten; and O to think from what a cause! Serena had given herself up to the influence of a vain curiosity! Soon had she cause to rue her folly; for most sadly was she beguiled by what could be nothing more than an illusion to ensnare and deceive her; the work of an enemy to her peace.

After a while, a thick mist suddenly fell like a cloud over every object around her. The very rocks and trees which sheltered her were no longer visible: The wind moaned, and the river rushed along in tumult as the roar of the waterfall became loud as rolling thunder. Serena trembled in every limb; her heart beat quick; she knew not what to do. Move from the spot of her concealment she dared not; she was on the verge of despair, when gradually the mist rose like a veil that had been thrown over the landscape, and now raised by an invisible hand. The rocks, woods, and waterfall once more were distinctly seen, but under a melancholy aspect; no sun-beam fell upon them; all was shadow and gloom. She looked down on the narrow pathway; but neither the beautiful sleeping youth, nor the lute by his side were to be seen; they ware gone; and she saw only the broken and mossy rocks wet with the spray and foam of the stream!

At length she arose, retraced her steps, and approached the chapel; but the vesper bell had long ceased ringing, and the doors of the chapel were closed--closed indeed, for the vesper service had been concluded half an hour before she reached the spot. Serena could net but feel ashamed of her folly; and she added to it by keeping the knowledge of it confined to her own bosom; for neither to Father Hilary, nor to the nurse did she tell what had happened.

She was, however, often seen stealing down the pathway. that led to Nathan's Kieve; for by a strange fascination she was fond of going there alone; although it was in that spot she first received those impressions which now rendered her so melancholy and unhappy. At length Father Hilary saw something was the matter, and obtained from her a confession of the truth, but only in part told; for she confined herself to the statement of having wasted her time in wandering up to the waterfall in Nathan's Kieve, and being too late for the vespers. She blushed, but was so ashamed to confess how much she had been led astray, that she said not one word about the musician, his attire, or the music. But Father Hilary was quite sufficiently shocked by what she confessed, and imposed upon her a very severe penance, namely, that she should take the ten marks given to her by the Baron to buy a splendid dress to wear at a high festival to be held at the castle, and should expend the same in the purchase of

A SILVER BELL,

on which she must cause to be engraved an image of herself attired as a penitent, with her hair hanging down her back, and carrying a taper in her hand, in token of sorrow for what she had done amiss. Serena obeyed, and purchased the silver bell, of which I here give the picture.

This Father Hilary presented in her name to the little chapel situated on the hill above Nathan's Kieve.

But though this was done, and though Serena had worn her old robes at the high festival of Tintagel, to the amusement of all her gaily-clad young friends, who tittered at her shabby apparel and envied her pretty looks, and though she had taken care that her many visits to the waterfall should never again interfere with the hour of ringing the vesper bell; yet was she dull and melancholy. Her spirits flagged, indeed they had never returned with their natural vivacity since that unluckly day on which she committed so great a fault. Still she longed and sighed once more to hear the charming music, and to see the handsome and gaily dressed minstrel. But she was always disappointed in her hopes and expectations.

At length she became so unhappy that she told all her secret to nurse Judy. Now, nurse Judy, though good-natured was not a very wise counsellor, for fearing Father Hilary would put the young lady to a more severe penance than the former did he know all the truth, she gave her very wrong advice as will presently be seen.

She told Serena that she was convinced all that had happened to her was a Pixy delusion, brought about by some of those malignant and spiteful beings, who it was well known were powerful in Nathan's Kieve, and more especially over any one who had been negligent in the performance of their duty. She did not doubt that the music was the work of their spells; and as to the beautiful musician, she felt certain that he was nothing more than some mischievous imp, who had assumed that appearance on purpose to deceive her.

In order therefore to counteract these spells, she persuaded Serena to go and consult old Swillpot, the famous Cornish wizard, who dwelt near the waterfall at Nathan's Kieve, and who, nurse Judy said, was noted for being a kind wizard in his way, that was if he entertained no spite against the person who came to consult him; and more especially if the individual gave him a purse full of money, and a jar of strong rich metheglin or mead, which had been made at the full of the moon (then considered the best time for making it), and was three years old at least. Judy declared, that she had metheglin in her own particular cupboard which had been made under all the quarters of the moon, and old Swillpot should have that decocted at the full.

Serena, though not without fear, took all the money she had and put it into her purse; she took also Judy's jar of metheglin, which was so large she found it difficult to carry it under her cloak, and set out for the wizard's dwelling.

A very poor and miserable cottage was not the most agreeable place for so delicate a young lady as Serena to visit; but she was unhappy and wanted relief, and so she did not care to be nice, but after a gentle rap at once entered the dwelling. She was civilly received by old Swillpot, more especially when he handled the purse, and took

the jar of metheglin, and with a good-humoured chuckle tucked it under his arm. He then bade Serena sit down, and he would presently taIk with her.

Old Swillpot had not much the look of a wizard, for he was stout and burly, had a round full face, not unlike the moon (as that luminary is painted on the face of a clock), a very round red nose, and a beard so thick and long it reached quite down to his waist. He was in an exceeding good humour, placed himself at the head of a little table, produced a brown loaf and some Cornish cheese, as hard as if it had been cut out of the rocks, or from one of the Cornish mines, bustled up to his cupboard, produced a couple of horn cups, opened the jar, and very heartily pressed Serena to partake with him some of her own choice metheglin. This, with a smack of the lips, he pronounced to be excellent, clear as amber, rich as the honey from which it was originally made, and fit for the king himself if he ever came into Cornwall. Serena, not to offend him, just tasted the cup, and then would have proceeded to tell her tale; butt the charms of the metheglin were so much greater than those of the young lady in the estimation of old Swillpot, that not until he had half emptied the jar would he hear a word she had to say.

At last he seemed a little boozy with the strength of the potation; as he sat, neither quite awake nor yet asleep, tapping his fingers on the table, his nose three times redder than it was before, he bade her tell her story, and gave a yawn and a lengthened hum at the end of every sentence, to let her know how very attentive he was to her discourse.

He then leaned back in his chair, looked wise, considered, made a snatch at a fine tabby cat that was rubbing herself against the side of his chair, took her up on his knee, and rubbed her hair the wrong way, as she raised up her tail till it reached his chin and brushed his beard. After consulting either his own thoughts, or the motion of the cat's tail, it was doubtful which, he very solemnly assured Serena, that all her sufferings and uneasiness proceeded from a wicked delusion--that, in fact, she had been Pixy-led in the most injurious manner. Having said this, he proceeded to the subject of her cure--to free her from the powerful spell under which she was still labouring; to cure her vain desire to hear again the mysterious music, and to see the handsome musician, which so disturbed her peace. Lastly, as what she had to do must be performed at the Kieve, and in sight of the waterfall, at the full of the moon, he offered to accompany her to the spot. As the moon would be at the full that very night, he said no time should be lost; it was therefore agreed that they should set out together. fore departing, old Swillpot tucked the jar, containing the remainder of the metheglin, under his arm, and so the speedily gained the place of their destination.

But what were the fears and astonishment of Serena, when, on arriving there, the wizard directed her to climb up to the top of the rock which forms the natural arch in front of the waterfall, and lies directly over what may truly be styled a boiling and foaming cauldron. And, when there, he directed her to perform certain magical rites to appease the Pixies; for Pixies, he still declared, had been her foes

In what all these rites consisted, I do not know; but, watching the moon till a cloud passed over her disk, and then repeating certain words of mysterious signification, were among them. Lastly, she was enjoined to stay on the rock till she heard, even above the fall of the water, the scream of a night-bird that was said to haunt the ravine, and there to make the most dismal shrieks that could be imagined. No one knew where it had a nest. It was popularly believed to be the spirit of the great enchanter, Merlin, thus inhabiting the body of a bird for a certain term of years. Merlin, it was said, had been a cruel enemy to the Pixies. Serena was directed to watch; and when she saw something dark come sailing over the rocks above, on out-spread wings, and with loud screams prepare to dash itself into the midst of the fall, then was she to address it in a form of words, which the wizard instructed her how to repeat. This done, she might descend from the rock, and would no more be troubled with any mischievous spells or fancies.

Serena, with much fear, and a quickly-beating heart, managed to ascend the rock, and to take her perilous stand upon the natural arch above the rapid and roaring flood: she did all as commanded. At length she heard a flapping of wings, and saw the dark form of a majestic bird, whose plumage shone bright and silvery in the moonbeams, rise from among the trees. Instantly she addressed it, in a firm and plaintive tone--

"Bird of night, 'tis time to leave

Thy nest, and seek St. Nathan's Kieve;

Bird of power o'er Pixy dells,

Disenchant me from their spells.

Give me freedom from their thrall,

Ere thou seek'st yon waterfall;

Drive from me idle Fancy's mood,

Or drown my folly in the flood."

Serena, as she spoke these last words, raised herself hastily from the summit of the rock on which she was so precariously placed. At that very moment the bird with outspread wings dashed against the moon-illumined waterfall, she lost her footing and tottered. Before she could regain her balance, old Swillpot, as fast as he could make the effort, stepped forward to give assistance. Unfortunately whilst Serena had been performing the rites he dictated, in order to keep the night air from chilling his stomach, he had emptied into it the remaining half of the jar of metheglin, so that he was a little more unsteady than before; and neither his foot in stepping, nor his hand in helping, were so much under his control as at all to be sure of their purpose; and he bungled so terribly in trying to give aid, that his foot slipped, and having caught Serena by the arm, down he pushed her; and both were soused into the water. Swillpot was nearer to the banks, and some how or other managed to scramble out.

But not so the unfortunate young lady; she had been pushed so completely over the rock by the tipsy wizard, that she fell at once into a pool which lay immediately below it; the most deep and dangerous in the whole course of the stream. Poor Serena was seen no more. But long did her memory survive her unhappy fate; long was her story told as a sad example of so young and so lovely a creature being led into folly by her vain and idle curiosity.

Old Swillpot, who was not of an unkind heart, though he did not possess a very clear head, was so shocked and concerned at what had happened, owing to his having bewildered his brains and rendered his footing unsteady, by making too free with the metheglin; that, as the very severest penance he could possibly inflict upon himself, he renounced strong drink for ever after. And old nurse Judy was so vexed and angry with herself for having recommended her young lady to go and consult him, and for sending such an old fool, as she called him, her best and stoutest metheglin, that she took the resolution never more to give away one drop of it to any mortal creature; and so well did she observe this determination that it never more went down any throat but her own. And as a reward for keeping so strictly her purpose, old Swillpot's red nose seemed to have passed from his face to her own.

It is said to this day, when the moon is at the full, and her beams sparkle, like filaments of diamonds on the beautiful waterfall of Nathan's Kieve, Serena's Silver Bell is heard ringing in a slow and melancholy cadence, like a funeral chime; though the chapel to which it was given has long been destroyed, and neither the belfry nor bell are any more to be found.

NOTES TO "THE LADY OF THE SILVER BELL."

For the wild Pixy incidents which suggested this tale, I am indebted to my husband, the Rev. E. A. Bray, who many years since commenced a little poem on the subject, which is lost.