The Pirates Own Book, by Charles Ellms

THE LIFE OF CHARLES GIBBS.

Containing an Account of his Atrocities committed in the West Indies.

This atrocious and cruel pirate, when very young became addicted to vices uncommon in youths of his age, and so far from the gentle reproof and friendly admonition, or the more severe chastisement of a fond parent, having its intended effect, it seemed to render him still worse, and to incline him to repay those whom he ought to have esteemed as his best friends and who had manifested so much regard for his welfare, with ingratitude and neglect. His infamous career and ignominious death on the gallows; brought down the "grey hairs of his parents in sorrow to the grave." The poignant affliction which the infamous crimes of children bring upon their relatives ought to be one of the most effective persuasions for them to refrain from vice.

Charles Gibbs was born in the state of Rhode Island, in 1794; his parents and connexions were of the first respectability. When at school, he was very apt to learn, but so refractory and sulky, that neither the birch nor good counsel made any impression on him, and he was expelled from the school.

He was now made to labor on a farm; but having a great antipathy to work, when about fifteen years of age, feeling a great inclination to roam, and like too many unreflecting youths of that age, a great fondness for the sea, he in opposition to the friendly counsel of his parents, privately left them and entered on board the United States sloop-of-war, Hornet, and was in the action when she captured the British sloop-of-war Peacock, off the coast of Pernambuco. Upon the return of the Hornet to the United States, her brave commander, Capt. Lawrence, was promoted for his gallantry to the command of the unfortunate Chesapeake, and to which he was followed by young Gibbs, who took a very distinguished part in the engagement with the Shannon, which resulted in the death of Lawrence and the capture of the Chesapeake. Gibbs states that while on board the Chesapeake the crew previous to the action, were almost in a state of mutiny, growing out of the non payment of the prize money, and that the address of Capt. Lawrence was received by them with coldness and murmurs.

After the engagement, Gibbs became with the survivors of the crew a prisoner of war, and as such was confined in Dartmoor prison until exchanged.

After his exchange, he returned to Boston, where having determined to abandon the sea, he applied to his friends in Rhode Island, to assist him in commencing business; they accordingly lent him one thousand dollars as a capital to begin with. He opened a grocery in Ann Street, near what was then called the Tin Pot, a place full of abandoned women and dissolute fellows. As he dealt chiefly in liquor, and had a "License to retail Spirits," his drunkery was thronged with customers. But he sold his groceries chiefly to loose girls who paid him in their coin, which, although it answered his purpose, would neither buy him goods or pay his rent, and he found his stock rapidly dwindling away without his receiving any cash to replenish it. By dissipation and inattention his new business proved unsuccessful to him. He resolved to abandon it and again try the sea for a subsistence. With a hundred dollars in his pocket, the remnant of his property, he embarked in the ship John, for Buenos Ayres, and his means being exhausted soon after his arrival there, he entered on board a Buenos Ayrean privateer and sailed on a cruise. A quarrel between the officers and crew in regard to the division of prize money, led eventually to a mutiny; and the mutineers gained the ascendancy, took possession of the vessel, landed the crew on the coast of Florida, and steered for the West Indies, with hearts resolved to make their fortunes at all hazards, and where in a short time, more than twenty vessels were captured by them and nearly Four Hundred Human Beings Murdered!

Havana was the resort of these pirates to dispose of their plunder; and Gibbs sauntered about this place with impunity and was acquainted in all the out of the way and bye places of that hot bed of pirates the Regla. He and his comrades even lodged in the very houses with many of the American officers who were sent out to take them. He was acquainted with many of the officers and was apprised of all their intended movements before they left the harbor. On one occasion, the American ship Caroline, was captured by two of their piratical vessels off Cape Antonio. They were busily engaged in landing the cargo, when the British sloop-of-war, Jearus, hove in sight and sent her barges to attack them. The pirates defended themselves for some time behind a small four gun battery which they had erected, but in the end were forced to abandon their own vessel and the prize and fly to the mountains for safety. The Jearus found here twelve vessels burnt to the water's edge, and it was satisfactorily ascertained that their crews, amounting to one hundred and fifty persons had been murdered. The crews, if it was thought not necessary otherways to dispose of them were sent adrift in their boats, and frequently without any thing on which they could subsist a single day; nor were all so fortunate thus to escape. "Dead men can tell no tales," was a common saying among them; and as soon as a ship's crew were taken, a short consultation was held; and if it was the opinion of a majority that it would be better to take life than to spare it, a single nod or wink from the captain was sufficient; regardless of age or sex, all entreaties for mercy were then made in vain; they possessed not the tender feelings, to be operated upon by the shrieks and expiring groans of the devoted victims! there was a strife among them, who with his own hands could despatch the greatest number, and in the shortest period of time.

Without any other motives than to gratify their hellish propensities (in their intoxicated moments), blood was not unfrequently and unnecessarily shed, and many widows and orphans probably made, when the lives of the unfortunate victims might have been spared, and without the most distant prospect of any evil consequences (as regarded themselves), resulting therefrom.

Gibbs states that sometime in the course of the year 1819, he left Havana and came to the United States, bringing with him about $30,000. He passed several weeks in the city of New York, and then went to Boston, whence he took passage for Liverpool in the ship Emerald. Before he sailed, however, he has squandered a large part of his money by dissipation and gambling. He remained in Liverpool a few months, and then returned to Boston. His residence in Liverpool at that time is satisfactorily ascertained from another source besides his own confession. A female now in New York was well acquainted with him there, where, she says, he lived like a gentleman, with apparently abundant means of support. In speaking of his acquaintance with this female he says, "I fell in with a woman, who I thought was all virtue, but she deceived me, and I am sorry to say that a heart that never felt abashed at scenes of carnage and blood, was made a child of for a time by her, and I gave way to dissipation to drown the torment. How often when the fumes of liquor have subsided, have I thought of my good and affectionate parents, and of their Godlike advice! But when the little monitor began to move within me, I immediately seized the cup to hide myself from myself, and drank until the sense of intoxication was renewed. My friends advised me to behave myself like a man, and promised me their assistance, but the demon still haunted me, and I spurned their advice."

In 1826, he revisited the United States, and hearing of the war between Brazil and the Republic of Buenos Ayres, sailed from Boston in the brig Hitty, of Portsmouth, with a determination, as he states, of trying his fortune in defence of a republican government. Upon his arrival he made himself known to Admiral Brown, and communicated his desire to join their navy. The admiral accompanied him to the Governor, and a Lieutenant's commission being given him, he joined a ship of 34 guns, called the 'Twenty Fifth of May.' "Here," says Gibbs, "I found Lieutenant Dodge, an old acquaintance, and a number of other persons with whom I had sailed. When the Governor gave me the commission he told me they wanted no cowards in their navy, to which I replied that I thought he would have no apprehension of my cowardice or skill when he became acquainted with me. He thanked me, and said he hoped he should not be deceived; upon which we drank to his health and to the success of the Republic. He then presented me with a sword, and told me to wear that as my companion through the doubtful struggle in which the republic was engaged. I told him I never would disgrace it, so long as I had a nerve in my arm. I remained on board the ship in the capacity of 5th Lieutenant, for about four months, during which time we had a number of skirmishes with the enemy. Having succeeded in gaining the confidence of Admiral Brown, he put me in command of a privateer schooner, mounting two long 24 pounders and 46 men. I sailed from Buenos Ayres, made two good cruises, and returned safely to port. I then bought one half of a new Baltimore schooner, and sailed again, but was captured seven days out, and carried into Rio Janeiro, where the Brazilians paid me my change. I remained there until peace took place, then returned to Buenos Ayres, and thence to New York.

"After the lapse of about a year, which I passed in travelling from place to place, the war between France and Algiers attracted my attention. Knowing that the French commerce presented a fine opportunity for plunder, I determined to embark for Algiers and offer my services to the Dey. I accordingly took passage from New York, in the Sally Ann, belonging to Bath, landed at Barcelona, crossed to Port Mahon, and endeavored to make my way to Algiers. The vigilance of the French fleet prevented the accomplishment of my design, and I proceeded to Tunis. There finding it unsafe to attempt a journey to Algiers across the desert, I amused myself with contemplating the ruins of Carthage, and reviving my recollections of her war with the Romans. I afterwards took passage to Marseilles, and thence to Boston."

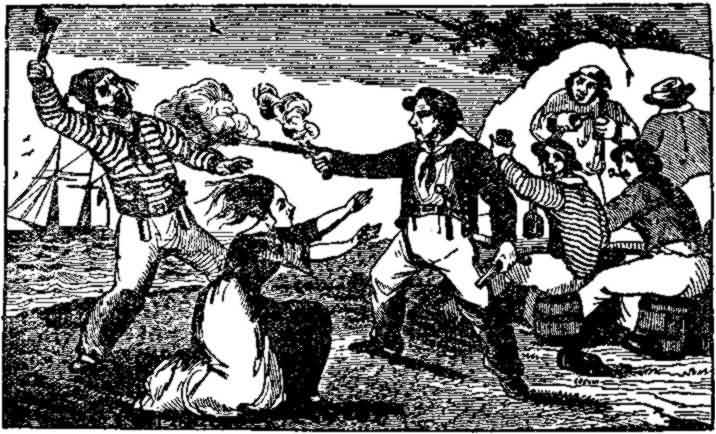

An instance of the most barbarous and cold blooded murder of which the wretched Gibbs gives an account in the course of his confessions, is that of an innocent and beautiful female of about 17 or 18 years of age! she was with her parents a passenger on board a Dutch ship, bound from Curracoa to Holland; there were a number of other passengers, male and female, on board, all of whom except the young lady above-mentioned were put to death; her unfortunate parents were inhumanly butchered before her eyes, and she was doomed to witness the agonies and to hear the expiring, heart-piercing groans of those whom she held most dear, and on whom she depended for protection! The life of their wretched daughter was spared for the most nefarious purposes--she was taken by the pirates to the west end of Cuba, where they had a rendezvous, with a small fort that mounted four guns--here she was confined about two months, and where, as has been said by the murderer Gibbs, "she received such treatment, the bare recollection of which causes me to shudder!" At the expiration of the two months she was taken by the pirates on board of one of their vessels, and among whom a consultation was soon after held, which resulted in the conclusion that it would be necessary for their own personal safety, to put her to death! and to her a fatal dose of poison was accordingly administered, which soon proved fatal! when her pure and immortal spirit took its flight to that God, whom, we believe, will avenge her wrongs! her lifeless body was then committed to the deep by two of the merciless wretches with as much unconcern, as if it had been that of the meanest brute! Gibbs persists in the declaration that in this horrid transaction he took no part, that such was his pity for this poor ill-fated female, that he interceded for her life so long as he could do it with safety to his own!

Gibbs carrying the Dutch Girl on board his Vessel.

Gibbs in his last visit to Boston remained there but a few days, when he took passage to New Orleans, and there entered as one of the crew on board the brig Vineyard; and for assisting in the murder of the unfortunate captain and mate of which, he was justly condemned, and the awful sentence of death passed upon him! The particulars of the bloody transaction (agreeable to the testimony of Dawes and Brownrigg, the two principal witnesses,) are as follows: The brig Vineyard, Capt. William Thornby, sailed from New Orleans about the 9th of November, for Philadelphia, with a cargo of 112 bales of cotton, 113 hhds. sugar, 54 casks of molasses and 54,000 dollars in specie. Besides the captain there were on board the brig, William Roberts, mate, six seamen shipped at New Orleans, and the cook. Robert Dawes, one of the crew, states on examination, that when, about five days out, he was told that there was money on board, Charles Gibbs, E. Church and the steward then determined to take possession of the brig. They asked James Talbot, another of the crew, to join them. He said no, as he did not believe there was money in the vessel. They concluded to kill the captain and mate, and if Talbot and John Brownrigg would not join them, to kill them also. The next night they talked of doing it, and got their clubs ready. Dawes dared not say a word, as they declared they would kill him if he did; as they did not agree about killing Talbot and Brownrigg, two shipmates, it was put off. They next concluded to kill the captain and mate on the night of November 22, but did not get ready; but, on the night of the 23d, between twelve and one o'clock, as Dawes was at the helm, saw the steward come up with a light and a knife in his hand; he dropt the light and seizing the pump break, struck the captain with it over the head or back of the neck; the captain was sent forward by the blow, and halloed, oh! and murder! once; he was then seized by Gibbs and the cook, one by the head and the other by the heels, and thrown overboard. Atwell and Church stood at the companion way, to strike down the mate when he should come up. As he came up and enquired what was the matter they struck him over the head--he ran back into the cabin, and Charles Gibbs followed him down; but as it was dark, he could not find him--Gibbs came on deck for the light, with which he returned. Dawes' light being taken from him, he could not see to steer, and he in consequence left the helm, to see what was going on below. Gibbs found the mate and seized him, while Atwell and Church came down and struck him with a pump break and a club; he was then dragged upon deck; they called for Dawes to come to them, and as he came up the mate seized his hand, and gave him a death gripe! three of them then hove him overboard, but which three Dawes does not know; the mate when cast overboard was not dead, but called after them twice while in the water! Dawes says he was so frightened that he hardly knew what to do. They then requested him to call Talbot, who was in the forecastle, saying his prayers; he came up and said it would be his turn next! but they gave him some grog, and told him not to be afraid, as they would not hurt him; if he was true to them, he should fare as well as they did. One of those who had been engaged in the bloody deed got drunk, and another became crazy!

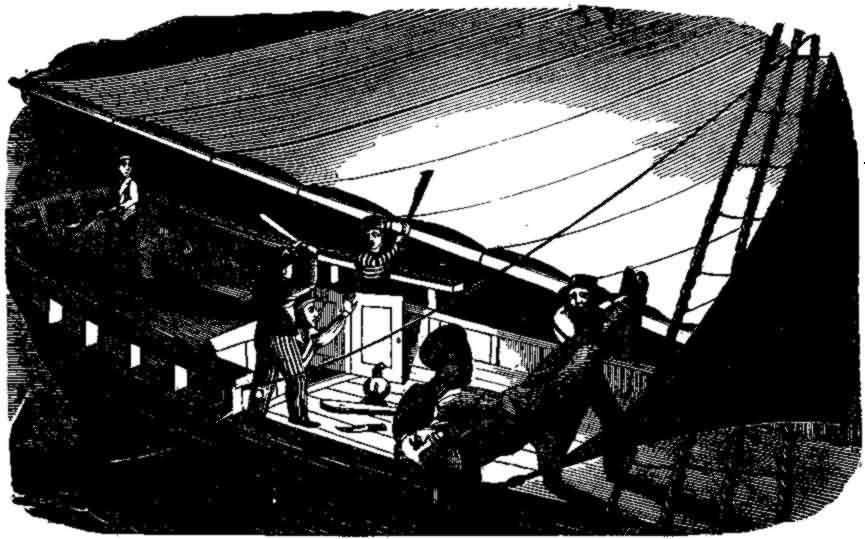

Gibbs shooting a comrade.

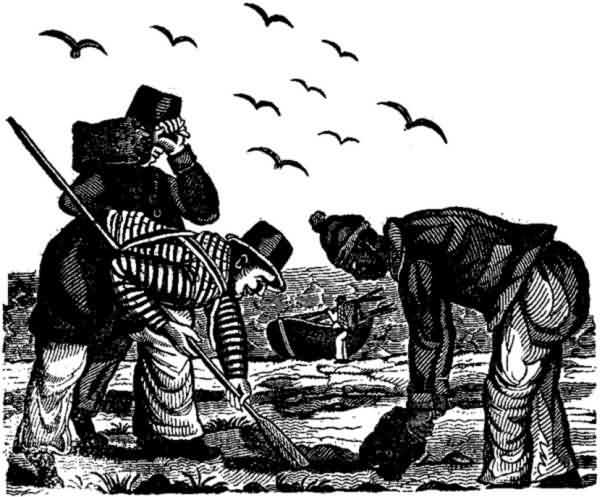

After killing the captain and mate, they set about overhauling the vessel, and got up one keg of Mexican dollars. They then divided the captain's clothes, and money--about 40 dollars, and a gold watch. Dawes, Talbot and Brownrigg, (who were all innocent of the murder,) were obliged to do as they were commanded--the former, who was placed at the helm, was ordered to steer for Long Island. On the day following, they divided several kegs of the specie, amounting to five thousand dollars each--they made bags and sewed the money up. After this division, they divided the remainder of the money without counting it. On Sunday, when about 15 miles S.S.E. of Southampton Light, they got the boats out and put half the money in each--they then scuttled the vessel and set fire to it in the cabin, and took to the boats. Gibbs, after the murder, took charge of the vessel as captain. From the papers they learnt that the money belonged to Stephen Girard. With the boats they made the land about daylight. Dawes and his three companions were in the long boat; the others, with Atwell, were in the jolly boat--on coming to the bar the boats struck--in the long boat, they threw overboard a trunk of clothes and a great deal of money, in all about 5000 dollars--the jolly boat foundered; they saw the boat fill, and heard them cry out, and saw them clinging to the masts--they went ashore on Barron Island, and buried the money in the sand, but very lightly. Soon after they met with a gunner, whom they requested to conduct them where they could get some refreshments. They were by him conducted to Johnson's (the only man living on the island,) where they staid all night--Dawes went to bed at about 10 o'clock--Jack Brownrigg set up with Johnson, and in the morning told Dawes that he had told Johnson all about the murder. Johnson went in the morning with the steward for the clothes, which were left on the top of the place where they buried the money, but does not believe they took away the money.

Captain Thornby murdered and thrown overboard by Gibbs and the steward.

The prisoners, (Gibbs and Wansley,) were brought to trial at the February term of the United States Court, holden in the city of New York; when the foregoing facts being satisfactorily proved, they were pronounced guilty, and on the 11th March last, the awful sentence of the law was passed upon them in the following affecting and impressive manner:--The Court opened at 11 o'clock, Judge Betts presiding. A few minutes after that hour, Mr. Hamilton, District Attorney, rose and said--May it please the Court, Thomas J. Wansley, the prisoner at the bar, having been tried by a jury of his country, and found guilty of the murder of Captain Thornby, I now move that the sentence of the Court be pronounced upon that verdict.

Gibbs and Wansley burying the Money.

By the Court. Thomas J. Wansley, you have heard what has been said by the District Attorney--by the Grand Jury of the South District of New York, you have been arraigned for the wilful murder of Captain Thornby, of the brig Vineyard; you have been put upon your trial, and after a patient and impartial hearing, you have been found Guilty. The public prosecutor now moves for judgment on that verdict; have you any thing to say, why the sentence of the law should not be passed upon you?

Thomas J. Wansley. I will say a few words, but it is perhaps of no use. I have often understood that there is a great deal of difference in respect of color, and I have seen it in this Court. Dawes and Brownrigg were as guilty as I am, and these witnesses have tried to fasten upon me greater guilt than is just, for their life has been given to them. You have taken the blacks from their own country, to bring them here to treat them ill. I have seen this. The witnesses, the jury, and the prosecuting Attorney consider me more guilty than Dawes, to condemn me--for otherwise the law must have punished him; he should have had the same verdict, for he was a perpetrator in the conspiracy. Notwithstanding my participating, they have sworn falsely for the purpose of taking my life; they would not even inform the Court, how I gave information of money being on board; they had the biggest part of the money, and have sworn falsely. I have said enough. I will say no more.

By the Court. The Court will wait patiently and hear all you have to say; if you have any thing further to add, proceed.

Wansley then proceeded. In the first place, I was the first to ship on board the Vineyard at New Orleans, I knew nobody; I saw the money come on board. The judge that first examined me, did not take my deposition down correctly. When talking with the crew on board, said the brig was an old craft, and when we arrived at Philadelphia, we all agreed to leave her. It was mentioned to me that there was plenty of money on board. Henry Atwell said "let's have it." I knew no more of this for some days. Atwell came to me again and asked "what think you of taking the money." I thought it was a joke, and paid no attention to it. The next day he said they had determined to take the brig and money, and that they were the strongest party, and would murder the officers, and he that informed should suffer with them. I knew Church in Boston, and in a joke asked him how it was made up in the ship's company; his reply, that it was he and Dawes. There was no arms on board as was ascertained; the conspiracy was known to the whole company, and had I informed, my life would have been taken, and though I knew if I was found out my life would be taken by law, which is the same thing, so I did not inform. I have committed murder and I know I must die for it.

By the Court. If you wish to add any thing further you will still be heard.

Wansley. No sir, I believe I have said enough.

The District Attorney rose and moved for judgment on Gibbs, in the same manner as in the case of Wansley, and the Court having addressed Gibbs, in similar terms, concluded by asking what he had to say why the sentence of the law should not now be passed upon him.

Charles Gibbs said, I wish to state to the Court, how far I am guilty and how far I am innocent in this transaction. When I left New Orleans, I was a stranger to all on board, except Dawes and Church. It was off Tortugas that Atwell first told me there was money on board, and proposed to me to take possession of the brig. I refused at that time. The conspiracy was talked of for some days, and at last I agreed that I would join. Brownrigg, Dawes, Church, and the whole agreed that they would. A few days after, however, having thought of the affair, I mentioned to Atwell, what a dreadful thing it was to take a man's life, and commit piracy, and recommended him to "abolish," their plan. Atwell and Dawes remonstrated with me; I told Atwell that if ever he would speak of the subject again, I would break his nose. Had I kept to my resolution I would not have been brought here to receive my sentence. It was three days afterwards that the murder was committed. Brownrigg agreed to call up the captain from the cabin, and this man, (pointing to Wansley,) agreed to strike the first blow. The captain was struck and I suppose killed, and I lent a hand to throw him overboard. But for the murder of the mate, of which I have been found guilty, I am innocent--I had nothing to do with that. The mate was murdered by Dawes and Church; that I am innocent of this I commit my soul to that God who will judge all flesh--who will judge all murderers and false swearers, and the wicked who deprive the innocent of his right. I have nothing more to say.

By the Court. Thomas J. Wansley and Charles Gibbs, the Court has listened to you patiently and attentively; and although you have said something in your own behalf, yet the Court has heard nothing to affect the deepest and most painful duty that he who presides over a public tribunal has to perform.

You, Thomas J. Wansley, conceive that a different measure of justice has been meted out to you, because of your color. Look back upon your whole course of life; think of the laws under which you have lived, and you will find that to white or black, to free or bond, there is no ground for your allegations; that they are not supported by truth or justice. Admit that Brownrigg and Dawes have sworn falsely; admit that Dawes was concerned with you; admit that Brownrigg is not innocent; admit, in relation to both, that they are guilty, the whole evidence has proved beyond a doubt that you are guilty; and your own words admit that you were an active agent in perpetrating this horrid crime. Two fellow beings who confided in you, and in their perilous voyage called in your assistance, yet you, without reason or provocation, have maliciously taken their lives.

If, peradventure, there was the slightest foundation for a doubt of your guilt, in the mind of the Court, judgment would be arrested, but there is none; and it now remains to the Court to pronounce the most painful duty that devolves upon a civil magistrate. The Court is persuaded of your guilt; it can form no other opinion. Testimony has been heard before the Court and Jury--from that we must form our opinion. We must proceed upon testimony, ascertain facts by evidence of witnesses, on which we must inquire, judge and determine as to guilt or innocence, by that evidence alone. You have been found guilty. You now stand for the last time before an earthly tribunal, and by your own acknowledgments, the sentence of the law falls just on your heads. When men in ordinary cases come under the penalty of the law there is generally some palliative--something to warm the sympathy of the Court and Jury. Men may be led astray, and under the influence of passion have acted under some long smothered resentment, suddenly awakened by the force of circumstances, depriving him of reason, and then they may take the life of a fellow being. Killing, under that kind of excitement, might possibly awaken some sympathy, but that was not your case; you had no provocation. What offence had Thornby or Roberts committed against you? They entrusted themselves with you, as able and trustworthy citizens; confiding implicitly in you; no one act of theirs, after a full examination, appears to have been offensive to you; yet for the purpose of securing the money you coolly determined to take their lives--you slept and deliberated over the act; you were tempted on, and yielded; you entered into the conspiracy, with cool and determined calculation to deprive two human beings of their lives, and it was done.

You, Charles Gibbs, have said that you are not guilty of the murder of Roberts; but were you not there, strongly instigating the murderers on, and without stretching out a hand to save him?--It is murder as much to stand by and encourage the deed, as to stab with a knife, strike with a hatchet, or shoot with a pistol. It is not only murder in law, but in your own feelings and in your own conscience. Notwithstanding all this, I cannot believe that your feelings are so callous, so wholly callous, that your own minds do not melt when you look back upon the unprovoked deeds of yourselves, and those confederated with you.

You are American citizens--this country affords means of instruction to all: your appearance and your remarks have added evidence that you are more than ordinarily intelligent; that your education has enabled you to participate in the advantages of information open to all classes. The Court will believe that when you were young you looked with strong aversion on the course of life of the wicked. In early life, in boyhood, when you heard of the conduct of men, who engaged in robbery--nay more, when you heard of cold blooded murder--how you must have shrunk from the recital. Yet now, after having participated in the advantages of education, after having arrived at full maturity, you stand here as robbers and murderers.

It is a perilous employment of life that you have followed; in this way of life the most enormous crimes that man can commit, are MURDER AND PIRACY. With what detestation would you in early life have looked upon the man who would have raised his hand against his officer, or have committed piracy! yet now you both stand here murderers and pirates, tried and found guilty--you Wansley of the murder of your Captain, and you, Gibbs, of the murder of your Mate. The evidence has convicted you of rising in mutiny against the master of the vessel, for that alone, the law is DEATH!--of murder and robbery on the high seas, for that crime, the law adjudges DEATH--of destroying the vessel and embezzling the cargo, even for scuttling and burning the vessel alone the law is DEATH; yet of all these the evidence has convicted you, and it only remains now for the Court to pass the sentence of the law. It is, that you, Thomas J. Wansley and Charles Gibbs be taken hence to the place of confinement, there to remain in close custody, that thence you be taken to the place of execution, and on the 22d April next, between the hours of 10 and 4 o'clock, you be both publicly hanged by the neck until you are DEAD--and that your bodies be given to the College of Physicians and Surgeons for dissection.

The Court added, that the only thing discretionary with it, was the time of execution; it might have ordered that you should instantly have been taken from the stand to the scaffold, but the sentence has been deferred to as distant a period as prudent--six weeks. But this time has not been granted for the purpose of giving you any hope for pardon or commutation of the sentence;--just as sure as you live till the twenty-second of April, as surely you will suffer death--therefore indulge not a hope that this sentence will be changed!

The Court then spoke of the terror in all men of death!--how they cling to life whether in youth, manhood or old age. What an awful thing it is to die! how in the perils of the sea, when rocks or storms threaten the loss of the vessel, and the lives of all on board, how the crew will labor, night and day, in the hope of escaping shipwreck and death! alluded to the tumult, bustle and confusion of battle--yet even there the hero clings to life. The Court adverted not only to the certainty of their coming doom on earth, but to THINK OF HEREAFTER--that they should seriously think and reflect of their FUTURE STATE! that they would be assisted in their devotions no doubt, by many pious men.

When the Court closed, Charles Gibbs asked, if during his imprisonment, his friends would be permitted to see him. The Court answered that that lay with the Marshal, who then said that no difficulty would exist on that score. The remarks of the Prisoners were delivered in a strong, full-toned and unwavering voice, and they both seemed perfectly resigned to the fate which inevitably awaited them. While Judge Betts was delivering his address to them, Wansley was deeply affected and shed tears--but Gibbs gazed with a steady and unwavering eye, and no sign betrayed the least emotion of his heart. After his condemnation, and during his confinement, his frame became somewhat enfeebled, his face paler, and his eyes more sunken; but the air of his bold, enterprising and desperate mind still remained. In his narrow cell, he seemed more like an object of pity than vengeance--was affable and communicative, and when he smiled, exhibited so mild and gentle a countenance, that no one would take him to be a villain. His conversation was concise and pertinent, and his style of illustration quite original.

Gibbs was married in Buenos Ayres, where he has a child now

living. His wife is dead. By a singular concurrence of

circumstances, the woman with whom he became acquainted in

Liverpool, and who is said at that time to have borne a decent

character, was lodged in the same prison with himself. During his

confinement he wrote her two letters--one of them is subjoined,

to gratify the perhaps innocent curiosity which is naturally felt

to know the peculiarities of a man's mind and feelings under such

circumstances, and not for the purpose of intimating a belief

that he was truly penitent. The reader will be surprised with the

apparent readiness with which he made quotations from

Scripture.

"BELLEVUE PRISON, March 20, 1831.

"It is with regret that I take my pen in hand to address you with these few lines, under the great embarrassment of my feelings placed within these gloomy walls, my body bound with chains, and under the awful sentence of death! It is enough to throw the strongest mind into gloomy prospects! but I find that Jesus Christ is sufficient to give consolation to the most despairing soul. For he saith, that he that cometh to me I will in no ways cast out. But it is impossible to describe unto you the horror of my feelings. My breast is like the tempestuous ocean, raging in its own shame, harrowing up the bottom of my soul! But I look forward to that serene calm when I shall sleep with Kings and Counsellors of the earth. There the wicked cease from troubling, and there the weary are at rest!--There the prisoners rest together--they hear not the voice of the oppressor; and I trust that there my breast will not be ruffled by the storm of sin--for the thing which I greatly feared has come upon me. I was not in safety, neither had I rest; yet trouble came. It is the Lord, let him do what seemeth to him good. When I saw you in Liverpool, and a peaceful calm wafted across both our breasts, and justice no claim upon us, little did I think to meet you in the gloomy walls of a strong prison, and the arm of justice stretched out with the sword of law, awaiting the appointed period to execute the dreadful sentence. I have had a fair prospect in the world, at last it budded, and brought forth the gallows. I am shortly to mount that scaffold, and to bid adieu to this world, and all that was ever dear to my breast. But I trust when my body is mounted on the gallows high, the heavens above will smile and pity me. I hope that you will reflect on your past, and fly to that Jesus who stands with open arms to receive you. Your character is lost, it is true. When the wicked turneth from the wickedness that they have committed, they shall save their soul alive.

"Let us imagine for a moment that we see the souls standing before the awful tribunal, and we hear its dreadful sentence, depart ye cursed into everlasting fire. Imagine you hear the awful lamentations of a soul in hell. It would be enough to melt your heart, if it was as hard as adamant. You would fall upon your knees and plead for God's mercy, as a famished person would for food, or as a dying criminal would for a pardon. We soon, very soon, must go the way whence we shall ne'er return. Our names will be struck off the records of the living, and enrolled in the vast catalogues of the dead. But may it ne'er be numbered with the damned.--I hope it will please God to set you at your liberty, and that you may see the sins and follies of your life past. I shall now close my letter with a few words which I hope you will receive as from a dying man; and I hope that every important truth of this letter may sink deep in your heart, and be a lesson to you through life.

"Rising griefs distress my soul,

And tears on tears successive

roll--

For many an evil voice is

near,

To chide my woes and mock my

fear--

And silent memory weeps

alone,

O'er hours of peace and gladness

known.

"I still remain your sincere friend, CHARLES GIBBS."

In another letter which the wretched Gibbs wrote after his condemnation to one who had been his early friend, he writes as follows:--"Alas! it is now, and not until now, that I have become sensible of my wicked life, from my childhood, and the enormity of the crime, for which I must shortly suffer an ignominious death!--I would to God that I never had been born, or that I had died in my infancy!--the hour of reflection has indeed come, but come too late to prevent justice from cutting me off--my mind recoils with horror at the thoughts of the unnatural deeds of which I have been guilty!--my repose rather prevents than affords me relief, as my mind, while I slumber, is constantly disturbed by frightful dreams of my approaching awful dissolution!"

On Friday, April twenty-second, Gibbs and Wansley paid the

penalty of their crimes. Both prisoners arrived at the gallows

about twelve o'clock, accompanied by the marshal, his aids, and

some twenty or thirty United States' marines. Two clergymen

attended them to the fatal spot, where everything being in

readiness, and the ropes adjusted about their necks, the Throne

of Mercy was fervently addressed in their behalf. Wansley then

prayed earnestly himself, and afterwards joined in singing a

hymn. These exercises concluded, Gibbs addressed the spectators

nearly as follows:

MY DEAR FRIENDS,

My crimes have been heinous--and although I am now about to suffer for the murder of Mr. Roberts, I solemnly declare my innocence of the transaction. It is true, I stood by and saw the fatal deed done, and stretched not forth my arm to save him; the technicalities of the law believe me guilty of the charge--but in the presence of my God--before whom I shall be in a few minutes--I declare I did not murder him.

I have made a full and frank confession to Mr. Hopson, which probably most of my hearers present have already read; and should any of the friends of those whom I have been accessary to, or engaged in the murder of, be now present, before my Maker I beg their forgiveness--it is the only boon I ask--and as I hope for pardon through the blood of Christ, surely this request will not be withheld by man, to a worm like myself, standing as I do, on the very verge of eternity! Another moment, and I cease to exist--and could I find in my bosom room to imagine that the spectators now assembled had forgiven me, the scaffold would have no terrors, nor could the precept which my much respected friend, the marshal of the district, is about to execute. Let me then, in this public manner, return my sincere thanks to him, for his kind and gentlemanly deportment during my confinement. He was to me like a father, and his humanity to a dying man I hope will be duly appreciated by an enlightened community.

My first crime was piracy, for which my life

would pay for forfeit on conviction; no punishment could be

inflicted on me further than that, and therefore I had nothing to

fear but detection, for had my offences been millions of times

more aggravated than they are now, death must have

satisfied all.

Gibbs having concluded, Wansley began. He said he might be called a pirate, a robber, and a murderer, and he was all of these, but he hoped and trusted God would, through Christ, wash away his aggravated crimes and offences, and not cast him entirely out. His feelings, he said, were so overpowered that he hardly knew how to address those about him, but he frankly admitted the justness of the sentence, and concluded by declaring that he had no hope of pardon except through the atoning blood of his Redeemer, and wished that his sad fate might teach others to shun the broad road to ruin, and travel in that of virtue, which would lead to honor and happiness in this world, and an immortal crown of glory in that to come.

He then shook hands with Gibbs, the officers, and clergymen--their caps were drawn over their faces, a handkerchief dropped by Gibbs as a signal to the executioner caused the cord to be severed, and in an instant they were suspended in air. Wansley folded his hands before him, soon died with very trifling struggles. Gibbs died hard; before he was run up, and did not again remove them, but after being near two minutes suspended, he raised his right hand and partially removed his cap, and in the course of another minute, raised the same hand to his mouth. His dress was a blue round-about jacket and trousers, with a foul anchor in white on his right arm. Wansley wore a white frock coat, trimmed with black, with trousers of the same color.

After the bodies had remained on the gallows the usual time, they were taken down and given to the surgeons for dissection.

Gibbs was rather below the middle stature, thick set and powerful. The form of Wansley was a perfect model of manly beauty.