A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume II

By Jacob Bryant

TAR, TOR, TARIT.

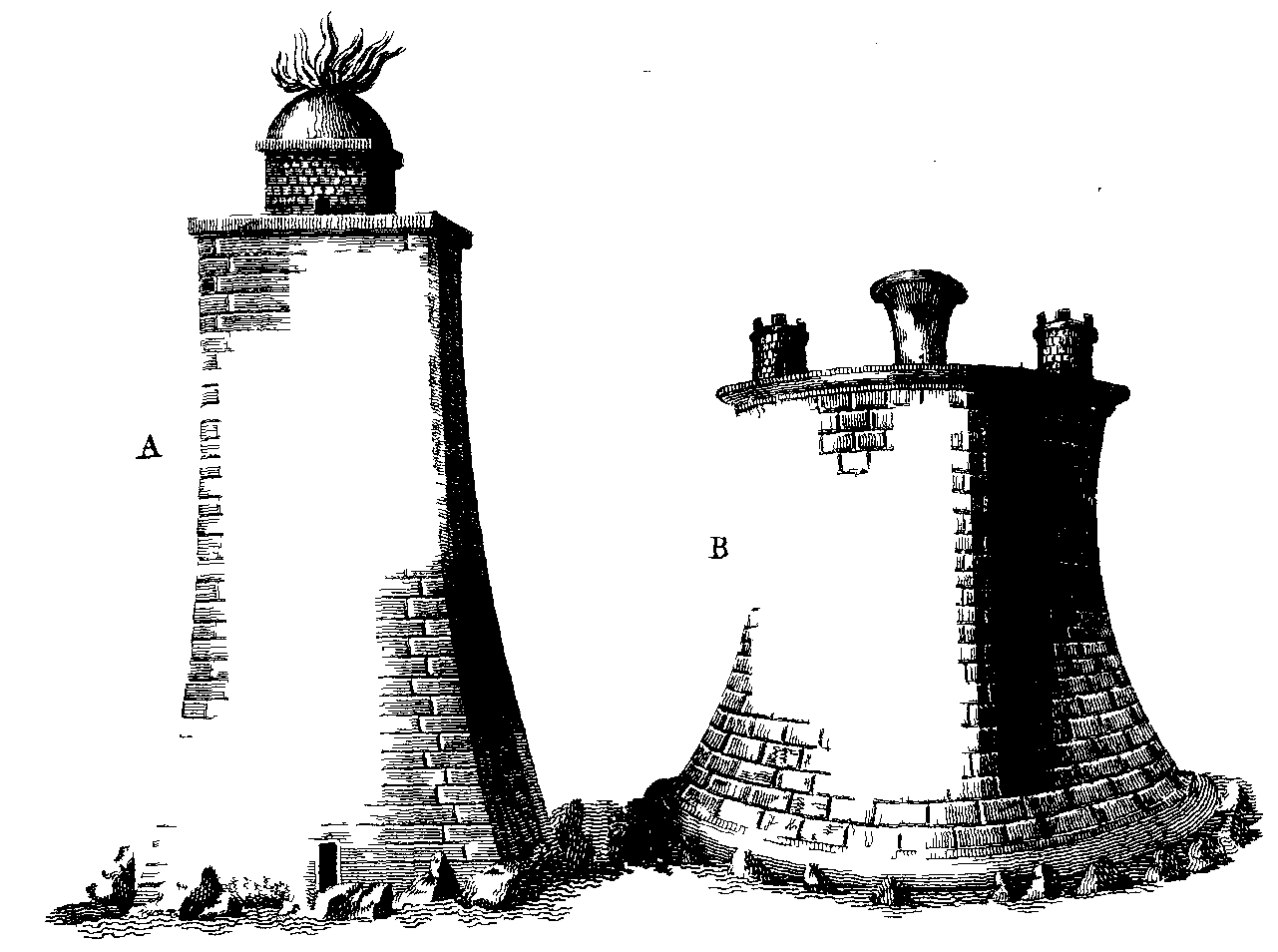

I have taken notice of the fears and apprehensions, under which the first navigators must necessarily have been, when they traversed unknown seas; and were liable to be entangled among the rocks, and shelves of the deep: and I mentioned the expedients of which they made use to obviate such difficulties, and to render the coast less dangerous. They built upon every hill, and promontory, where they had either commerce or settlement, obelisks, and towers, which they consecrated to some Deity. These served in a twofold capacity, both as seamarks by day, and for beacons by night. And as people in those times made only coasting voyages, they continually went on shore with offerings, in order to gain the assistance of the God, whoever there presided; for these towers were temples, and oftentimes richly furnished and endowed. They were built sometimes on artificial mounds; but generally on natural eminences, that they might be seen at a great distance. They were called by the Amonians, who first erected them, [230]Tar, and Tor; the same as the תור of the Chaldees, which signified both a hill and tower. They were oftentimes compounded, and styled Tor-Is, or fire towers: on account of the light which they exhibited, and the fires which were preserved in them. Hence came the turris of the Romans; and the τυρις, τυῤῥις, τυρσις, τυρσος, of the Greeks. The latter, when the word Tor occurred in antient history, often changed it to ταυρος, a bull; and invented a number of idle stories in consequence of this change. The Ophite God Osiris, the same as Apollo, was by the Amonians styled Oph-El, and Ope-El: and there was upon the Sinus Persicus a city Opis, where his rites were observed. There seems likewise to have been a temple sacred to him, named Tor-Opel; which the Greeks rendered Ταυροπολος. Strabo speaks of such an oracular temple; and says, that it was in the island Icaria, towards the mouth of the Tigris: [231]Νησον Ικαριον, και ἱερον Απολλωνος ἁγιον εν αυτῃ, και μαντειον Ταυροπολου. Here, instead of Osiris, or Mithras, the serpent Deity, the author presents us with Apollo, the manager of bulls.

One of the principal and most antient settlements of the Amonians upon the ocean was at Gades; where a prince was supposed to have reigned, named Geryon. The harbour at Gades was a very fine one; and had several Tor, or Towers to direct shipping: and as it was usual to imagine the Deity, to whom the temple was erected, to have been the builder, this temple was said to have been built by Hercules. All this the Grecians took to themselves: they attributed the whole to the hero of Thebes: and as he was supposed to conquer wherever he came, they made him subdue Geryon; and changing the Tor, or Towers, into so many head of cattle, they [232]describe him as leading them off in triumph over the Pyranees and Alpes, to Hetruria, and so on to Calabria. From thence, for what reason we know not, he swims them over to Messana in Sicily: and after some stay he swims with them through the sea back again, all the while holding by one of their horns. The bulls of Colchis, with which Jason was supposed to have engaged, were probably of the same nature and original. The people of this country were Amonians, and had once a [233]mighty trade; for the security of which they erected at the entrance of the Phasis towers. These served both as light-houses, and temples; and were sacred to Adorus. They were on this account called Tynador, whence the Greeks formed Tyndarus, Tyndaris, and Tyndaridæ. They were built after some, which stood near the city [234]Parætonium of Egypt; and they are alluded to by the geographer Dionysius:

[235]Παρ δε μυχον Ποντοιο, μετα χθονα Τυνδαριδαων,

Κολχοι ναιεταουσιν επηλυδες Αιγυπτοιο.

Colchis was styled Cutaia, and had been early occupied by the sons of Chus. The chief city, whence the country has been in general denominated, was from its situation called Cal-Chus, and Col-Chus, the hill, or place of Chus. This by the Greeks was rendered Colchis: but as travellers are not uniform in expressing foreign terms, some have rendered what was Colchian, Chalcian, and from Colchus they have formed Χαλκος, brass. The Chalcian towers being moreover interpreted ταυροι, bulls, a story took its rise about the brazen bulls of Colchis. Besides this, there was in these towers a constant fire kept up for the direction of ships by night: whence the bulls were said to breath fire.

We however sometimes meet with sacred towers, which were really denominated Tauri from the worship of the mystic bull, the same as the Apis, and Mneuis of Egypt. Such was probably the temple of Minotaurus in Crete, where the [236]Deity was represented under an emblematical figure; which consisted of the body of a man with the head of a bull. In Sicily was a promontory Taurus, mentioned by Diodorus Siculus; which was called also Tauromenium. He acquaints us, that Hanno the Carthaginian sent his Admiral with orders παραπλειν επι τον λοφον καλουμενον Ταυρον, to sail along the coast to the promontory named Taurus. This Taurus, he thinks, was afterwards named Ταυρομενιον, Tauromenium, from the people who settled, and [237]remained there: as if this were the only place in the world where people settled and remained. It was an antient compound, and no part of it of Grecian [238]original. Tauromenium is the same as Menotaurium reversed: and the figure of the Deity was varied exactly in the same manner; as is apparent from the coins and engravings which have been found in Sicily. The Minotaur is figured as a man with the head of a bull; the Tauromen as a bull with the face of a [239]man.

Among the [240]Hetrurians this term seems to have been taken in a more enlarged sense; and to have signified a city, or town fortified. When they settled in Italy, they founded many places of strength; and are reputed to have been the first who introduced the art of fortification. [241]Τυρσηνοι πρωτον εφευρον την τειχοποιϊαν. Hence the word Tar, and Tur, is often found in the composition of names, which relate to people of this country. They worshipped the Sun, styled Zan, and Zeen; whose temples were called Tur-Zeen: and in consequence of it one of the principal names by which their country was distinguished, was Turzenia. The Scholiast upon Lycophron mentions it as [242]Χωραν απο Τυρσηνου κληθεισαν Τυρσηνιαν, a region, which from Tur-Seen was named Tursenia. The Poet above takes notice of two persons by the names of Tarchon, and Turseen. [243]Ταρχων τε, και Τυρσηνος, αιθωνες λυκοι. From Tarchon there was a city and district named [244]Tarcunia; from whence came the family of the Tarquins, or Tarquinii, so well known in the history of [245]Rome. The Amonians esteemed every emanation of light a fountain; and styled it Ain, and Aines: and as they built lighthouses upon every island and insular promontory, they were in consequence of it called Aines, Agnes, Inis, Inesos, Nesos, Nees: and this will be found to obtain in many different countries and languages. The Hetrurians occupied a large tract of sea-coast; on which account they worshipped Poseidon: and one of their principal cities was Poseidonium. They erected upon their shores towers and beacons for the sake of their navigation, which they called Tor-ain: whence they had a still farther denomination of Tur-aini, and their country was named Tur-ainia; the Τυῤῥηνια of the later Greeks. All these appellations are from the same object, the edifices which they erected: even Hetruria seems to have been a compound of Ai-tur; and to have signified the land of Towers. Another name for buildings of this nature was Turit, or Tirit; which signified a tower or turret. I have often mentioned that temples have been mistaken for Deities, and places for persons. We have had an instance of this above; where Tarchon, and Tursenus are supposed to have been founders of colonies. Torone was a place in Macedonia; and signifies literally the Tower of the Sun. The Poets have formed out of it a female personage; and supposed her to have been the wife of [246]Proteus. So Amphi-Tirit is merely an oracular tower. This too has by the Poets been changed to a female, Amphitrite; and made the wife of Neptune. The name of Triton is a contraction of Tirit-On; and signifies the tower of the Sun, like Torone: but a Deity was framed from it, who was supposed to have had the appearance of a man upwards, but downwards to have been like a fish. From this emblematical representation we may judge of the figure of the real Deity; and be assured that it could be no other than that of Atargatis and Dagon. The [247]Hetrurians were thought to have been the inventors of trumpets: and in their towers upon the sea-coast there were people appointed to be continually upon the watch both by day and night; and to give a proper signal, if any thing happened extraordinary. This was done by a blast from the trumpet; and Triton was hence feigned to have been Neptune's trumpeter. He is accordingly described by Nonnus,

[248]Τυρσηνης Βαρυδουπον εχων σαλπιγγα θαλασσης·

as possessing the deep toned trumpet of the Hetrurian main. However in early times these brazen instruments were but little known: and people were obliged to make use of what was near at hand, the conchs of the sea, which every strand afforded. By sounding these, they gave signals from the top of the towers when any ship appeared: and this is the implement with which Triton is more commonly furnished. The antients divided the night into different watches; the last of which was called cockcrow: and in consequence of this they kept a cock in their Tirat, or Towers, to give notice of the dawn. Hence this bird was sacred to the Sun, and named Alector, Αλεκτωρ: which seems to be a compound out of the titles of that Deity, and of the tower set apart for his service: for all these towers were temples. Those styled Tritonian were oracular; as we may infer from the application made by the Argonauts. What Homer attributes to Proteus, Pindar ascribes to Triton. [249]Μαντευεται δε ὡς παρ' Ομηρῳ Πρωτευς, και παρα Πινδαρῳ Τριτων τοις Αργοναυταις. Pausanias mentions a tradition of a [250]Triton near Tanagra, who used to molest women, when they were bathing in the sea; and who was guilty of other acts of violence. He was at last found upon the beach overpowered with wine; and there slain. This Triton was properly a Tritonian, a priest of one of these temples: for the priests appear to have been great tyrants, and oftentimes very brutal. This person had used the natives ill; who took advantage of him, when overpowered with liquor, and put him to death.

The term Tor, in different parts of the world, occurs sometimes a little varied. Whether this happened through mistake, or was introduced for facility of utterance, is uncertain. The temple of the Sun, Tor Heres, in Phenicia was rendered Τριηρης, Trieres; the promontory Tor-Ope-On, in Caria, Triopon; Tor-Hamath, in Cyprus, Trimathus; Tor-Hanes, in India, Trinesia; Tor-Chom, or Chomus, in Palestine, Tricomis. In antient times the title of Anac was often conferred upon the Deities; and their temples were styled Tor-Anac, and Anac-Tor. The city Miletus was named [251]Anactoria: and there was an Heroüm at Sparta called Ανακτορον, Anactoron; where Castor and Pollux had particular honours, who were peculiarly styled Anactes. It was from Tor-Anac that Sicily was denominated Trinacis and Trinacia. This, in process of time, was still farther changed to Trinacria; which name was supposed to refer to the triangular form of the island. But herein was a great mistake; for, the more antient name was Trinacia, as is manifest from Homer:

[252]Ὁπποτε δη πρωτον πελασῃς ευεργεα νηα

Τρινακιῃ νησῳ.

And the name, originally, did not relate to the island in general, but to a part only, and that a small district near Ætna. This spot had been occupied by the first inhabitants, the Cyclopians, Lestrygons, and Sicani: and it had this name from some sacred tower which they built. Callimachus calls it, mistakenly, Trinacria, but says that it was near Ætna, and a portion of the antient Sicani.

[253]Αυε δ' αρ' Αιτνα,

Αυε δε Τρινακριη Σικανων ἑδος.

The island Rhodes was called [254]Trinacia, which was not triangular: so that the name had certainly suffered a variation, and had no relation to any figure. The city Trachin, Τραχιν, in Greece, was properly Tor-chun, turris sacra vel regia, like Tarchon in Hetruria. Chun and Chon were titles, said peculiarly to belong to Hercules: [255]Τον Ἡρακλην φησι κατα τον Αιγυπτιων διαλεκτον Κωνα λεγεσθαι. We accordingly find that this place was sacred to Hercules; that it was supposed to have been [256]founded by him; and that it was called [257]Heraclea.

I imagine that the trident of Poseidon was a mistaken implement; as it does not appear to have any relation to the Deity to whom it has been by the Poets appropriated. Both the towers on the sea-coast, and the beacons, which stood above them, had the name of Tor-ain. This the Grecians changed to Triaina, Τριαινα, and supposed it to have been a three-pronged fork. The beacon, or Torain, consisted of an iron or brazen frame, wherein were three or four tines, which stood up upon a circular basis of the same metal. They were bound with a hoop; and had either the figures of Dolphins, or else foliage in the intervals between them. These filled up the vacant space between the tines, and made them capable of holding the combustible matter with which they were at night filled. This instrument was put upon a high pole, and hung sloping sea-ward over the battlements of the tower, or from the stern of a ship: with this they could maintain, either a smoke by day, or a blaze by night. There was a place in Argos named [258]Triaina, which was supposed to have been so called from the trident of Neptune. It was undoubtedly a tower, and the true name Tor-ain; as may be shewn from the history with which it is attended. For it stood near a fountain, though a fountain of a different nature from that of which we have been speaking. The waters of Amumone rose here: which Amumone is a variation from Amim-On, the waters of the Sun. The stream rose close to the place, which was named Tor-ain, from its vicinity to the fountain.

Cerberus was the name of a place, as well as Triton and Torone, though esteemed the dog of hell. We are told by [259]Eusebius, from Plutarch, that Cerberus was the Sun: but the term properly signified the temple, or place, of the Sun. The great luminary was styled by the Amonians both Or and Abor; that is, light, and the parent of light: and Cerberus is properly Kir-Abor, the place of that Deity. The same temple had different names, from the diversity of the God's titles who was there worshipped. It was called TorCaph-El; which was changed to τρικεφαλος, just as Cahen-Caph-El was rendered κυνοκεφαλος: and Cerberus was hence supposed to have had three heads. It was also styled Tor-Keren, Turris Regia; which suffered a like change with the word above, being expressed τρικαρηνος: and Cahen Ades, or Cerberus, was hence supposed to have been a triple-headed monster. That these idle figments took their rise from names of places, ill expressed and misinterpreted, may be proved from Palæphatus. He abundantly shews that the mistake arose hence, though he does not point out precisely the mode of deviation. He first speaks of Geryon, who was supposed to have had three heads, and was thence styled τρικεφαλος. [260]Ην δε τοιονδε τουτο· πολις εστιν εν τῳ Ευξινῳ ποντῳ Τρικαρηνια καλουμενη κλ. The purport of the fable about Geryones is this: There was, upon the Pontus Euxinus, a city named Tricarenia; and thence came the history Γηρυονου του Τρικαρηνου, of Geryon the Tricarenian; which was interpreted, a man with three heads. He mentions the same thing of Cerberus. [261]Λεγουσι περι Κερβερου, ὡς κυων ην, εχων τρεις κεφαλας· δηλον δε ὁτι και ὁυτος απο της πολεως εκληθη Τρικαρηνος, ὡσπερ ὁ Γηρυονης. They say of Cerberus, that he was a dog with three heads: but it is plain that he was so called from a city named Tricaren, or Tricarenia, as well as Geryones. Palæphatus says, very truly, that the strange notion arose from a place. But, to state more precisely the grounds of the mistake, we must observe, that from the antient Tor-Caph-El arose the blunder about τρικεφαλος; as, from Tor-Keren, rendered Tricarenia, was formed the term τρικαρηνος: and these personages, in consequence of it, were described with three heads.

As I often quote from Palæphatus, it may be proper to say something concerning him. He wrote early: and seems to have been a serious and sensible person; one, who saw the absurdity of the fables, upon which the theology of his country was founded. In the purport of his name is signified an antiquarian; a person, who dealt in remote researches: and there is no impossibility, but that there might have casually arisen this correspondence between his name and writings. But, I think, it is hardly probable. As he wrote against the mythology of his country, I should imagine that Παλαιφατος, Palæphatus, was an assumed name, which he took for a blind, in order to screen himself from persecution: for the nature of his writings made him liable to much ill will. One little treatise of [262]Palæphatus about Orion is quoted verbatim by the Scholiast upon [263]Homer, who speaks of it as a quotation from Euphorion. I should therefore think, that Euphorion was the name of this writer: but as there were many learned men so called, it may be difficult to determine which was the author of this treatise.

Homer, who has constructed the noblest poem that was ever framed, from the strangest materials, abounds with allegory and mysterious description. He often introduces ideal personages, his notions of which he borrowed from the edifices, hills, and fountains; and from whatever savoured of wonder and antiquity. He seems sometimes to blend together two different characters of the same thing, a borrowed one, and a real; so as to make the true history, if there should be any truth at bottom, the more extraordinary and entertaining.

I cannot help thinking, that Otus and Ephiâltes, those gigantic youths, so celebrated by the Poets, were two lofty towers. They were building to Alohim, called [264]Aloëus; but were probably overthrown by an earthquake. They are spoken of by Pindar as the sons of Iphimedeia; and are supposed to have been slain by Apollo in the island Naxos.

They are also mentioned by Homer, who styles them γηγενεις, or earthborn: and his description is equally fine.

[266]Και ῥ' ετεκεν δυο παιδε, μινυνθαδιω δε γενεσθην,

Ωτον τ' αντιθεον, τηλεκλειτον τ' Εφιαλτην·

Ὁυς δη μηκιστους θρεψε ζειδωρος αρουρα,

Και πολυ καλλιστους μετα γε κλυτον Ωριωνα.

Εννεωροι γαρ τοι γε, και εννεαπηχεες ησαν

Ευρος, αταρ μηκος γε γενεσθην εννεοργυιοι.

Homer includes Orion in this description, whom he mentions elsewhere; and seems to borrow his ideas from a similar object, some tower, or temple, that was sacred to him. Orion was Nimrod, the great hunter in the Scriptures, called by the Greeks Nebrod. He was the founder of Babel, or Babylon; and is represented as a gigantic personage. The author of the Paschal Chronicle speaks of him in this light. [267]Νεβρωδ Γιγαντα, τον την Βαβυλωνιαν κτισαντα—ὁντινα καλουσιν Ωριωνα. He is called Alorus by Abydenus, and Apollodorus; which was often rendered with the Amonian prefix Pelorus. Homer describes him as a great hunter; and of an enormous stature, even superior to the Aloeidæ above mentioned.

[268]Τον δε μετ' Ωριωνα Πελωριον εισενοησα,

Θηρας ὁμου ειλευντα κατ' ασφοδελον λειμωνα.

The Poet styles him Pelorian; which betokens something vast, and is applicable to any towering personage, but particularly to Orion. For the term Pelorus is the name by which the towers of Orion were called. Of these there seems to have been one in Delos; and another of more note, to which Homer probably alluded, in Sicily; where Orion was particularly reverenced. The streight of Rhegium was a dangerous pass: and this edifice was erected for the security of those who were obliged to go through it. It stood near Zancle; and was called [269]Pelorus, because it was sacred to Alorus, the same as [270]Orion. There was likewise a river named from him, and rendered by Lycophron [271]Elorus. The tower is mentioned by Strabo; but more particularly by Diodorus Siculus. He informs us that, according to the tradition of the place, Orion there resided; and that, among other works, he raised this very mound and promontory, called Pelorus and Pelorias, together with the temple, which was situated upon it. [272]Ωριωνα προσχωσαι το κατα την Πελωριαδα κειμενον ακρωτηριον, και το τεμενος του Ποσειδωνος κατασκευασαι, τιμωμενον ὑπο των εγχωριων διαφεροντως. We find from hence that there was a tower of this sort, which belonged to Orion: and that the word Pelorion was a term borrowed from these edifices, and made use of metaphorically, to denote any thing stupendous and large. The description in Homer is of a mixed nature: wherein he retains the antient tradition of a gigantic person; but borrows his ideas from the towers sacred to him. I have taken notice before, that all temples of old were supposed to be oracular; and by the Amonians were called Pator and Patara. This temple of Orion was undoubtedly a Pator; to which mariners resorted to know the event of their voyage, and to make their offerings to the God. It was on this account styled Tor Pator; which being by the Greeks expressed τριπατωρ, tripator, gave rise to the notion, that this earthborn giant had three fathers.

[273]Ωριων τριπατωρ απο μητερος ανθορε γαιης.

These towers, near the sea, were made use of to form a judgment of the weather, and to observe the heavens: and those which belonged to cities were generally in the Acropolis, or higher part of the place. This, by the Amonians, was named Bosrah; and the citadel of Carthage, as well as of other cities, is known to have been so denominated. But the Greeks, by an unavoidable fatality, rendered it uniformly [274]βυρσα, bursa, a skin: and when some of them succeeded to Zancle [275]in Sicily, finding that Orion had some reference to Ouran, or Ouranus, and from the name of the temple (τριπατωρ) judging that he must have had three fathers, they immediately went to work, in order to reconcile these different ideas. They accordingly changed Ouran to ουρειν; and, thinking the misconstrued hide, βυρσα, no improper utensil for their purpose, they made these three fathers co-operate in a most wonderful manner for the production of this imaginary person; inventing the most slovenly legend that ever was devised. [276]Τρεις (θεοι) του σφαγεντος βοος βυρσῃ ενουρησαν, και εξ αυτης Ωριων εγενετο. Tres Dei in bovis mactati pelle minxerunt, et inde natus est Orion.

[230] Bochart Geog. Sacra. l. 1. c. 228. p. 524. of תור.

[231] Strabo. l. 16. p. 1110.

[232] Diodorus Siculus. l. 4. p. 231.

[233] Strabo. l. 11. p. 762.

[234] Τυνδαριοι σκοπελοι. Ptolemæus. p. 122. See Strabo. l. 17. p. 1150.

[235] Dionysius. v. 688. Pliny styles them oppida.

Oppida—in ripâ celeberrima, Tyndarida, Circæum, &c. l. 6. c. 4.

[236] The Minotaur was an emblematical representation of Menes, the same as Osiris; who was also called Dionusus, the chief Deity of Egypt. He was also the same as Atis of Lydia, whose rites were celebrated in conjunction with those of Rhea, and Cybele, the mother of the Gods. Gruter has an inscription, M. D. M. IDÆ, et ATTIDI MINOTAURO. He also mentions an altar of Attis Minoturannus. vol. 1. p. xxviii. n. 6.

[237] Diodor. Sicul. l. 16. p. 411.

[238] Meen was the moon: and Meno-Taurus signified Taurus Lunaris. It was a sacred emblem, of which a great deal will be said hereafter.

[239] See Paruta's Sicilia nummata.

[240] Τυρις, ὁ περιβολος του τειχους. Hesych. From whence we may infer, that any place surrounded with a wall or fortification might be termed a Tor or Turris.

Ταρχωνιον πολις Τυῤῥηνιας. Stephan. Byzant.

[241] Scholia upon Lycophron. v. 717.

[242] Scholia upon Lycophron. v. 1242.

The Poet says of Æneas, Παλιν πλανητην δεξεται Τυρσηνια. v. 1239.

[243] Lycophron. v. 1248.

[244] Ταρκυνια πολις Τυῤῥενιδος απο Ταρχωνος· το εθνικον Ταρκυνιος. Steph. Byzant.

[245] Strabo. l. 5. p. 336. Ταρκωνα, αφ' ὁυ Ταρκυνια ἡ πολις.

[246] Lycophron. v. 116.

Ἡ Τορωνε, γυνη Πρωτεως. Scholia ibidem.

[247] Τυῤῥηνοι σαλπιγγα. Tatianus Assyrius. p. 243.

[248] L. 17. p. 468.

[249] Scholia upon Lycophron. v. 754.

[250] Pausanias. l. 9. p. 749.

[251] Pausanias. l. 7. p. 524.

Δειμε δε τοι μαλα καλον Ανακτορον. Callimachus. Hymn to Apollo. v. 77.

[252] Homer. Odyss. λ. v. 105. Strabo supposes Trinakis to have been the modern name of the island; forgetting that it was prior to the time of Homer. l. 6. p. 407: he also thinks that it was called Trinacria from its figure: which is a mistake.

[253] Hymn to Diana. v. 56. I make no doubt but Callimachus wrote Τρινακια.

[254] Pliny. l. 5. c. 31.

[255] Etymolog. Magn.

[256] Stephanas Byzant.

[257] Τραχιν, ἡ νυν Ἡρακλεια καλουμενη. Hesych. or, as Athenæus represents it, more truly, Ἡρακλειαν, την Τραχινιαν καλεομενην. l. 11. p. 462.

[258] Τριαινα τοπος Αργους· ενθα την τριαιναν ορθην εστησεν ὁ Ποσειδων, συγγινομενος τη Αμυμωνη, και ευθυς κατ' εκεινο ὑδωρ ανεβλυσεν, ὁ και την επικλησιν εσχεν εξ Αμυμωνης. Scholia in Euripidis Phœniss. v. 195.

[259] Eusebius. Præp. Evan. l. 3. c. 11. p. 113.

[260] Palæphatus. p. 56.

[261] Ibid. p. 96.

[262] Palæphatus. p. 20.

[263] Iliad. Σ. v. 486.

[264] Diodorus Siculus. l. 3. p. 324.

[265] Pindar. Pyth. Ode 4. p. 243.

[266] Homer. Odyss. Λ. v. 306.

[267] Chron. Paschale. p. 36.

Νεβρωδ——καλουσιν Ωριωνα. Cedrenus. p. 14.

[268] Homer. Odyss. Λ. v. 571.

[269] Strabo. l. 3. p. 259.

[270] Alorus was the first king of Babylon; and the same person as Orion, and Nimrod. See Radicals. p. 10. notes.

[271] Ἑλωρος, ενθα ψυχρον εκβαλλει ποτον. Lycophron. v. 1033.

Ῥειθρων Ἑλωρου προσθεν. Idem. v. 1184. Ὁ ποταμος ὁ Ἑλωρος εσχε το ονομα απο τινος βασιλεως Ἑλωρου. Schol. ibid. There were in Sicily many places of this name; Πεδιον Ἑλωριον. Diodorus. l. 13. p. 148. Elorus Castellum. Fazellus. Dec. 1. l. 4. c. 2.

Via Helorina. Ἑλωρος πολις. Cluver. Sicilia Antiqua. l. 1. c. 13. p. 186.

[272] Diodorus Siculus. l. 4. p. 284.

[273] Nonni Dionysiaca. l. 13. p. 356.

[274] Κατα μεσην δε την πολιν ἡ ακροπολις, ἡν εκαλουν βυρσαν, οφρυς ἱκανως ορθια. Strabo. l. 17. p. 1189.

See also Justin. l. 18. c. 5. and Livy. l. 34. c. 62.

[275] Ζαγκλη πολις Σικελιας—απο Ζαγκλου του γηγενους. Stephanus Byzant.

[276] Scholia in Lycophron. v. 328.

Index | Next: Tit And Tith