|

|

Mythical Monsters by Charles Gould 1886

CHAPTER XI.

THE CHINESE PHŒNIX.

FROM the date of the earliest examination of the literature of China, it has been customary among Sinologues to trace a fancied resemblance between a somewhat remarkable bird, which occupies an important position in the early traditions of that Empire, and the phœnix of Western authors. Some mythologists have even subsequently concluded that the Fung Hwang of the Chinese, the phœnix of the Greeks, the Roc of the Arabs, and the Garuda of the Hindoos, are merely national modifications of the same myth. I do not hold this opinion, and, in opposing it, purpose, in the future, to discuss each of these birds in detail, although in the present volume I treat only of the Fung Hwang.

The earliest notice of it is contained in the ’Rh Ya, which, with its usual brevity, simply informs us that the male is called Fung and the female Hwang; the commentator, Kwoh P‘oh, adding that the Shui Ying bird (felicitous and perfect—a synonym for it) has a cock's head, a snake's neck, a swallow's beak, a tortoise's back, is of five different colours, and more than six feet high. The ’Rh Ya Chen I, a later and supplementary edition of the former work, quotes the Shwoh Wan to the effect that the united name of the male and female bird is Fung Hwang, and that Tso's commentary on the 17th year of the Chao, says one appeared in the time of the Emperor Che (dynastic title, Shaou Haou). The original passage in the Tso Chuen is so interesting that I quote in extenso Dr. Legge's translation of it:—

“When my ancestor, Shaou-Haou Che, succeeded to the kingdom, there appeared at that time a phœnix, and therefore he arranged his government under the nomenclature of birds, making bird officers, and naming them after birds. There were so and so Phoenix bird, minister of the calendar; so and so Dark bird [the swallow], master of the equinoxes; so and so Pih Chaou [the shrike], master of the solstices; so and so Green bird [a kind of sparrow], master of the beginning (of spring and autumn); and so and so Carnation bird [the golden pheasant], master of the close (of spring and autumn). . . . The five Che [Pheasants] presided over the five classes of mechanics.

“So in previous reigns there had been cloud officers, fire officers, water officers, and dragon officers, according to omens.”

I think there is some connection between this old usage and the present or late system of tribe totems among the North American Indians. Thus we have Snake, Tortoise, Hare Indians, &c., and I hope some day to explain some of the obscure and apparently impossible passages of the Shan Hai King, in reference to strange tribes, upon what I may call the totem theory.

The Kin King, a small work devoted to ornithology, and professing to date back to the Tsin dynasty [A.D. 265 to 317], opens its pages with a description of the Fung Hwang, because, as it states, the Fung is the principal of the three hundred and sixty different species of birds. According to it, the Fung is like a swan in front and like a Lin behind; it enumerates its resemblances pretty much as the commentator in the ’Rh Ya gives them; but we now find a commencement of extraordinary attributes. Thus the head is supposed to have impressed on it the Chinese character expressing virtue, the poll that for uprightness, the back that for humanity; the heart is supposed to contain that of sincerity, and the wings to enfold in their clasp that of integrity; its foot imprints integrity; its low notes are like a bell, its high notes are like a drum. It is said that it will not peck living grass, and that it contains all the five colours.*

When it flies crowds of birds follow. When it appears, the monarch is an equitable ruler, and the kingdom has moral principles. It has a synonym, "the felicitous yen." According to the King Shun commentary upon the ’Rh Ya, it is about six feet in height. The young are called Yoh Shoh, and it is said that the markings of the five colours only appear when it is three years of age.†

There appears to have been another bird closely related to it, which is called the Lwan Shui. This, when first hatched, resembles the young Fung, but when of mature age it changes the five colours.

The Shăng Li Teu Wei I says of this, that when the world is peaceful its notes will be heard like the tolling of a bell, Pien Lwan [answering to our "ding-dong "]. During the Chao dynasty it was customary to hang a bell on the tops of vehicles, with a sound like that of the Lwan.‡ From another passage we learn that it was supposed to have different names according to a difference in colour. Thus, when the head and wings were red it was called the red Fung; when blue, the Yu Siang; when white, the Hwa Yih; when black, the Yin Chu; when yellow, the To Fu. Another quotation is to the effect that, when the Fung soars and the Lwan flies upwards, one hundred birds follow them. It is also stated that when either the Lwan or the Fung dies, one hundred birds peck up the earth and bury them.

Another author amplifies the fancied resemblances of the Fung, for in the Lun Yü Tseh Shwai Shing we find it stated that it has six resemblances and nine qualities. The former are: 1st, the head is like heaven; 2nd, the eye like the sun; 3rd, the back is like the moon; 4th, the wings like the wind; 5th, the foot is like the ground; 6th, the tail is like the woof. The latter are: 1st, the mouth contains commands; 2nd, the heart is conformable to regulations; 3rd, the ear is thoroughly acute in hearing; 4th, the tongue utters sincerity; 5th, the colour is luminous; 6th, the comb resembles uprightness; 7th, the spur is sharp and curved; 8th, the voice is sonorous; 9th, the belly is the treasure of literature.

When it crows, in walking, it utters "Quai she" [returning joyously]; when it stops crowing, "T‘i fee" [I carry assistance?]; when it crows at night it exclaims "Sin" [goodness]; when in the morning, "Ho si" [I congratulate the world]; when during its flight, "Long Tu che wo" [Long Tu knows me] and "Hwang che chu sz si" [truly Hwang has come with the Bamboos].* Hence it was that Confucius wished to live among the nine I [barbarian frontier countries] following the Fung's pleasure.

The Fung appears to have been fond of music, for, according to the Shu King, when you play the flute, in nine cases out of ten the Fung Wang comes to bear you company; while, according to the Odes, or Classic of Poetry, the Fung, in flying, makes the sound hwuihwui, and its wings carry it up to the heavens; and when it sings on the lofty mountain called Kwang, the Wu Tung tree flourishes,* and its fame spreads over the world.

The presence of the Fung was always an auspicious augury, and it was supposed that when heaven showed its displeasure at the conduct of the people during times of drought, of destruction of crops by insects (locusts), of disastrous famines, and of pestilence, the Fung Wang retired from the civilised country into the desert and forest regions.

It was classed with the dragon, the tortoise, and the unicorn as a spiritual creature, and its appearance in the gardens and groves denoted that the princes and monarch were equitable, and the people submissive and obedient.

Its indigenous home is variously indicated. Thus, in the Shan Hai King, it is stated to dwell in the Ta Hueh mountains, a range included in the third list of the southern mountains; it is also, in the third portion of the same work (treating of the Great Desert), placed in the south and in the west of the Great Desert, and more specifically as west of Kwan Lun.

There is also a tradition that it came from Corea; and the celebrated Chinese general, Sieh Jan Kwéi, who invaded and conquered that country in A.D. 668, is said to have ascended the Fung Hwang mountain there and seen the phœnix.

According to the Annals of the Bamboo Books phœnixes, male and female, arrived in the autumn, in the seventh month, in the fiftieth year of the reign of Hwang Ti (B.C. 2647), and the commentary states that some of them abode in the Emperor's eastern garden; some built their nests about the corniced galleries (of the palaces), and some sung in the courtyard, the females gambolling to the notes of the males.

The commentary of the same work adds that (among a variety of prodigies) the phœnix appeared in the seventieth year of the reign of Yaou (B.C. 2286), and again in the first year of Shun (B.C. 2255).

Kwoh P‘oh states that, during the times of the Han dynasty (commencing B.C. 206 and lasting until A.D. 23), the phœnixes appeared constantly.

In these later passages I have adopted the word phœnix, after Legge and other Sinologues, as a conventional admission; but, as will be seen from all the extracts given, there are but few grounds for identifying it, whether fabulous or not, with the phœnix of Greek mythology. It reappears in Japanese tradition under the name of the Ho and O (male and female), and, according to Kempfer, who calls it the Foo, "it is a chimerical but beautiful large bird of paradise, of near akin to the phœnix of the ancients. It dwells in the high regions of the air, and it hath this in common with the Ki-Rin (the equivalent of the Chinese Ki-Lin), that it never comes down from thence but upon the birth of a sesin (a man of incomparable understanding, penetration, and benevolence) or that of a great emperor, or upon some such other extraordinary occasion."

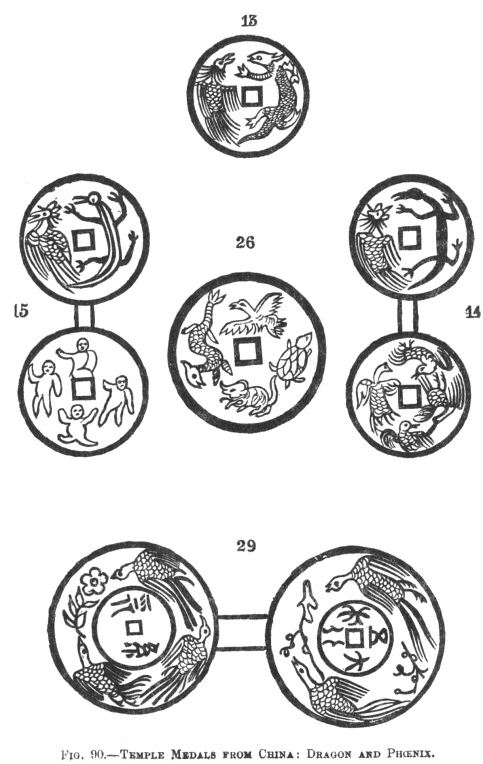

It is a common ornamentation in the Japanese temples; and I select, as an example, figures from some very beautiful panels in the Nichi-hong-wanji temple in Kioto. They depart widely from the original (Chinese) tradition, every individual presenting a different combination of gorgeous colours; they only agree in having two long central tail feathers projecting from a plumose, bird-of-paradise-like arrangement.

These can only be accepted as the evolution of an artist's fancy; nor can any opinion be arrived at from the figure of it illustrating the ’Rh Ya, of which I reproduce a fac-simile. I have already stated that Kwoh P‘oh's illustrations have been lost.

The frontispiece to this volume is reduced from a large and very beautiful painting on silk, which I was fortunate enough to procure in Shanghai, by an artist named Fang Heng, otherwise styled Sien Tang; it professes to be made according to the designs of ancient books. The original is, I believe, of some antiquity.

In this case the delineation of the bird shows a combination of the characters of the peacock, the pheasant, and the bird of paradise; the comb is like that of a pheasant. The tail is adorned with gorgeous eyes, like a peacock's, but fashioned more like that of an argus pheasant, the two middle tail feathers projecting beyond the others, while stiffened plumes, as I interpret the intention of the drawing, are made to project from the sides of the back, and above the wings, recalling those of the Semioptera Wallacii. The bird perches, in accordance with tradition, on the Wu-Tung tree. Without pretending to assert that this is an exact representation of the Tung, I fancy that it comes nearer to it than the ordinary Chinese and Japanese representations.

Looking to the history of the appearance of the Fung, the general description of its characteristics, and disregarding the supernatural qualities with which, probably, Taouist priests have invested it, I can only regard it as another example of an interesting and beautiful species of bird which has become extinct, as the dodo and so many others have, within historic times.

Its rare appearance and gorgeousness of plumage would cause its advent on any occasion to be chronicled, and a servile court would only too readily seize upon this pretext to flatter the reigning monarch and ascribe to his virtues a phenomenon which, after all, was purely natural.

Footnotes

369:* Black, red, azure (green, blue, or black), white, yellow.

369:† Many species of bird do not attain their mature plumage until long after they have attained adult size, as some among the gulls and birds of prey. I think I am right in saying that some of these latter only become perfect in their third year. We all know the story of the ugly duckling, and the little promise which it gave of its future beauty.

369:‡ According to Dr. Williams, the Lwan was a fabulous bird described as the essence of divine influence, and regarded as the embodiment of every grace and beauty, and that the argus pheasant was the type of it.

Dr. Williams says that it was customary to hang little bells from the phœnix that marked the royal cars.

370:* In reference to Hwang Ti (?) writing the Bamboo Books?

371:* The Wu Tung is the Eleococca verrucosa, according to Dr. William; others identify it with the Sterculia platanifolia. There is a Chinese proverb to the effect that without having Wu Tung trees you cannot expect to see phœnixes in your garden.