|

|

Mythical Monsters by Charles Gould 1886

CHAPTER I.

ON SOME REMARKABLE ANIMAL FORMS.

THE reasoning upon the question whether dragons, winged snakes, sea-serpents, unicorns, and other so-called fabulous monsters have in reality existed, and at dates coeval with man, diverges in several independent directions.

We have to consider:—

1.—Whether the characters attributed to these creatures are or are not so abnormal in comparison with those of known types, as to render a belief in their existence impossible or the reverse.

2.—Whether it is rational to suppose that creatures so formidable, and apparently so capable of self-protection, should disappear entirely, while much more defenceless species continue to survive them.

3.—The myths, traditions, and historical allusions from which their reality may be inferred require to be classified and annotated, and full weight given to the evidence which has accumulated of the presence of man upon the earth during ages long prior to the historic period, and which may have been ages of slowly progressive civilization, or perhaps cycles of alternate light and darkness, of knowledge and barbarism.

4.—Lastly, some inquiry may be made into the geographical conditions obtaining at the time of their possible existence.

It is immaterial which of these investigations is first entered upon, and it will, in fact, be more convenient to defer a portion of them until we arrive at the sections of this volume treating specifically of the different objects to which it is devoted, and to confine our attention for the present to those subjects which, from their nature, are common and in a sense prefatory to the whole subject.

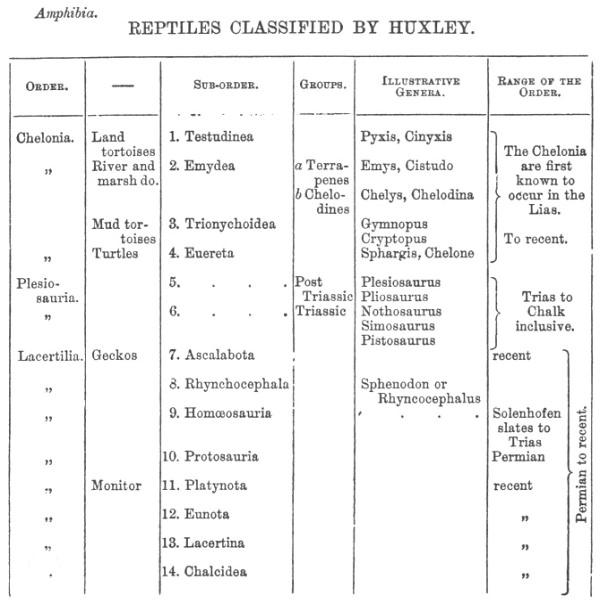

I shall therefore commence with a short examination of some of the most remarkable reptilian forms which are known to have existed, and for that purpose, and to show their general relations, annex the accompanying tables, compiled from the anatomy of vertebrated animals by Professor Huxley.

The most bird-like of reptiles, the Pterosauria, appear to have possessed true powers of flight; they were provided with wings formed by an expansion of the integument, and supported by an enormous elongation of the ulnar finger of the anterior limb. The generic differences are based upon the comparative lengths of the tail, and upon the dentition. In Pterodactylus (see Fig. 2, p. 18), the tail is very short, and the jaws strong, pointed, and toothed to their anterior extremities. In Rhamphorynchus (see Fig. 3, p. 18), the tail is very long and the teeth are not continuous to the extremities of the jaws, which are produced into toothless beaks. The majority of the species are small, and they are generally considered to have been inoffensive creatures, having much the habits and insectivorous mode of living of bats. One British species, however, from the white chalk of Maidstone, measures more than sixteen feet across the outstretched wings; and other forms recently discovered by Professor Marsh in the Upper Cretaceous deposits of Kansas, attain the gigantic proportions of nearly twenty-five feet for the same measurements; and although these were devoid of teeth (thus approaching the class Ayes still more closely), they could hardly fail, from their magnitude and powers of flight, to have been formidable, and must, with their weird aspects, and long outstretched necks and pointed heads, have been at least sufficiently alarming.

We need go no farther than these in search of creatures which would realise the popular notion of the winged dragon.

The harmless little flying lizards, belonging to the genus Draco, abounding in the East Indian archipelago, which have many of their posterior ribs prolonged into an expansion of the integument, unconnected with the limbs, and have a limited and parachute-like flight, need only the element of size, to render them also sufficiently to be dreaded, and capable of rivalling the Pterodactyls in suggesting the general idea of the same monster.

It is, however, when we pass to some of the other groups, that we find ourselves in the presence of forms so vast and terrible, as to more than realise the most exaggerated impression of reptilian power and ferocity which the florid imagination of man can conceive.

We have long been acquainted with numerous gigantic terrestrial Saurians, ranging throughout the whole of the Mesozoic formations, such as Iguanodon (characteristic of the Wealden), Megalosaurus (Great Saurian), and Hylæosaurus (Forest Saurian), huge bulky creatures, the last of which, at least, was protected by dermal armour partially produced into prodigious spines; as well as with remarkable forms essentially marine, such as Icthyosaurus (Fish-like Saurian), Plesiosaurus, &c., adapted to an oceanic existence and propelling themselves by means of paddles. The latter, it may be remarked, was furnished with a long slender swan-like neck, which, carried above the surface of the water, would present the appearance of the anterior portion of a serpent.

To the related land forms the collective term Dinosauria (from δεινός "terrible") has been applied, in signification of the power which their structure and magnitude imply that they possessed; and to the others that of Enaliosauria, as expressive of their adaptation to a maritime existence. Yet, wonderful to relate, those creatures which have for so many years commanded our admiration fade into insignificance in comparison with others which are proved, by the discoveries of the last few years, to have existed abundantly upon, or near to, the American continent during the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods, by which they are surpassed, in point of magnitude, as much as they themselves exceed the mass of the larger Vertebrata.

Take, for example, those referred to by Professor Marsh in the course of an address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in 1877, in the following terms: "The reptiles most characteristic of our American cretaceous strata are the Mososauria, a group with very few representatives in other parts of the world. In our cretaceous seas they rule supreme, as their numbers, size, and carnivorous habits enabled them to easily vanquish all rivals. Some were at least sixty feet in length, and the smallest ten or twelve. In the inland cretaceous sea from which the Rocky Mountains were beginning to emerge, these ancient 'sea-serpents' abounded, and many were entombed in its muddy bottom; on one occasion, as I rode through a valley washed out of this old ocean-bed, I saw no less than seven different skeletons of these monsters in sight at once. The Mososauria were essentially swimming lizards with four well-developed paddles, and they had little affinity with modern serpents, to which they have been compared."

Or, again, notice the specimens of the genus Cidastes, which are also described as veritable sea-serpents of those ancient seas, whose huge bones and almost incredible number of vertebræ show them to have attained a length of nearly two hundred feet. The remains of no less than ten of these monsters were seen by Professor Mudge, while riding through the Mauvaise Terres of Colorado, strewn upon the plains, their whitened bones bleached in the suns of centuries, and their gaping jaws armed with ferocious teeth, telling a wonderful tale of their power when alive.

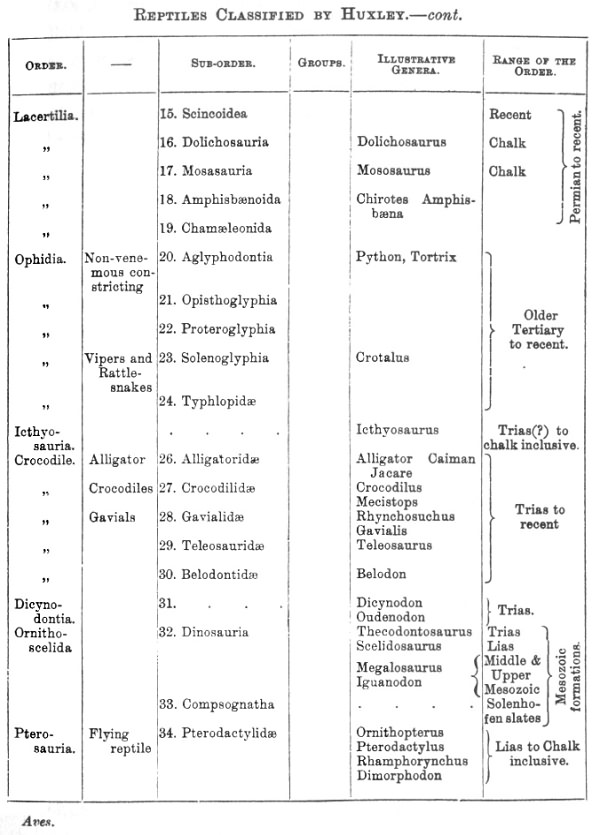

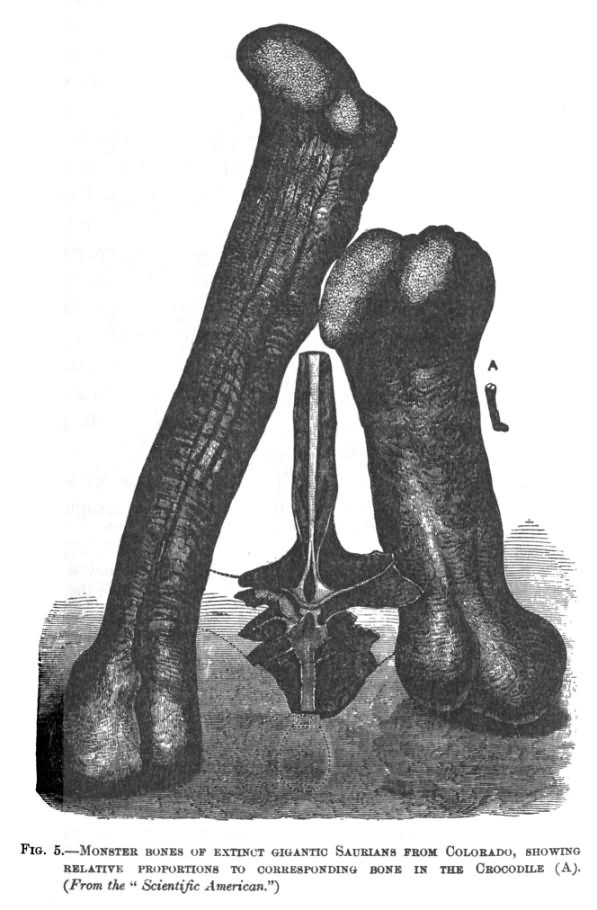

The same deposits have been equally fertile in the remains of terrestrial animals of gigantic size. The Titanosaurus montanus, believed to have been herbivorous, is estimated to have reached fifty or sixty feet in length; while other Dinosaurians of still more gigantic proportions, from the Jurassic beds of the Rocky Mountains, have been described by Professor Marsh. Among the discovered remains of Atlantosaurus immanis is a femur over six feet in length, and it is estimated from a comparison of this specimen with the same bone in living reptiles that this species, if similar in proportions to the crocodile, would have been over one hundred feet in length.

But even yet the limit has not been reached, and we hear of the discovery of the remains of another form, of such Titanic proportions as to possess a thigh-bone over twelve feet in length.

From these considerations it is evident that, on account of the dimensions usually assigned to them, no discredit can be attached to the existence of the fabulous monsters of which we shall speak hereafter; for these, in the various myths, rarely or never equal in size creatures which science shows to have existed in a comparatively recent geological age, while the quaintest conception could hardly equal the reality of yet another of the American Dinosaurs, Stegosaurus, which appears to have been herbivorous, and more or less aquatic in habit, adapted for sitting upon its hinder extremities, and protected by bony plate and numerous spines. It reached thirty feet in length. Professor Marsh considers that this, when alive, must have presented the strangest appearance of all the Dinosaurs yet discovered.

The affinities of birds and reptiles have been so clearly demonstrated of late years, as to cause Professor Huxley and many other comparative anatomists to bridge over the wide gap which was formerly considered to divide the two classes, and to bracket them together in one class, to which the name Sauropsidæ has been given.*

There are, indeed, not a few remarkable forms, as to the class position of which, whether they should be assigned to birds or reptiles, opinion was for a long time, and is in a few instances still, divided. It is, for example, only of late years that the fossil form Archæopteryx* (Fig. 4) from the Solenhofen slates, has been definitely relegated to the former, but arguments against this disposal of it have been based upon the beak or jaws being furnished with true teeth, and the feather of the tail attached to a series of vertebræ, instead of a single flattened one as in birds. It appears to have been entirely plumed, and to have had a moderate power of flight.

On the other hand, the Ornithopterus is only provisionally classed with reptiles, while the connection between the two classes is drawn still closer by the copious discovery of the birds from the Cretaceous formations of America, for which we are indebted to Professor Marsh.

The Lepidosiren, also, is placed mid-way between reptiles and fishes. Professor Owen and other eminent physiologists consider it a fish; Professor Bischoff and others, an amphibian reptile. It has a two-fold apparatus for respiration, partly aquatic, consisting of gills, and partly aerial, of true lungs.

So far, then, as abnormality of type is concerned, we have here instances quite as remarkable as those presented by most of the strange monsters with the creation of which mythological fancy has been credited.

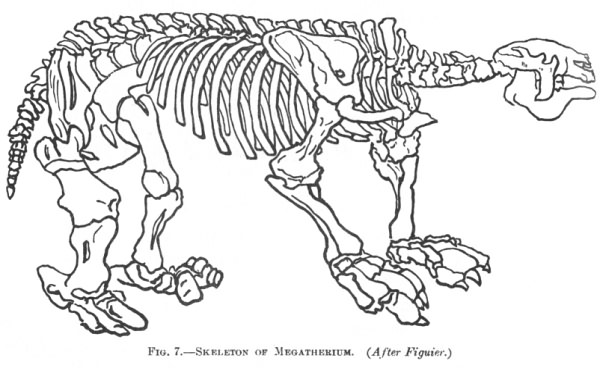

Among mammals I shall only refer to the Megatherium, which appears to have been created to burrow in the earth and to feed upon the roots of trees and shrubs, for which purpose every organ of its heavy frame was adapted. This Hercules among animals was as large as an elephant or rhinoceros of the largest species, and might well, as it has existed until a late date, have originated the myths, current among the Indians of South America, of a gigantic tunnelling or burrowing creature, incapable of supporting the light of day.*

Footnotes

38:* "It is now

generally admitted by biologists who have made a study of the

Vertebrata that birds have come down to us through the Dinosaurs,

and the close affinity of the latter with recent struthious birds

will hardly be questioned. The case amounts almost to a

demonstration if we compare with Dinosaurs their contemporaries,

the Mesozoic birds. The classes of birds and reptiles as now

living are separated by a gulf so profound that a few years since

it was cited by the opponents of evolution as the most important

break in the animal series, and one which that doctrine could not

bridge over. Since then, as Huxley has clearly shown, this gap

has been virtually filled by the discoveries of bird-like

reptiles and reptilian birds. Compsognathus and Archaeopteryx of

the old world, and Icthyornis and Hesperornis of the new, are the

stepping-stones by which the evolutionist of to-day leads the

doubting brother across the shallow remnant of the gulf, once

thought impassable."—Marsh.

38:* "It is now

generally admitted by biologists who have made a study of the

Vertebrata that birds have come down to us through the Dinosaurs,

and the close affinity of the latter with recent struthious birds

will hardly be questioned. The case amounts almost to a

demonstration if we compare with Dinosaurs their contemporaries,

the Mesozoic birds. The classes of birds and reptiles as now

living are separated by a gulf so profound that a few years since

it was cited by the opponents of evolution as the most important

break in the animal series, and one which that doctrine could not

bridge over. Since then, as Huxley has clearly shown, this gap

has been virtually filled by the discoveries of bird-like

reptiles and reptilian birds. Compsognathus and Archaeopteryx of

the old world, and Icthyornis and Hesperornis of the new, are the

stepping-stones by which the evolutionist of to-day leads the

doubting brother across the shallow remnant of the gulf, once

thought impassable."—Marsh.

39:* Professor Carl Vogt regards the Archaeopteryx "as neither reptile nor bird, but as constituting an intermediate type. He points out that there is complete homology between the scales or spines of reptiles and the feathers of birds. The feather of the bird is only a reptile's scale further developed, and the reptile's scale is a feather which has remained in the embryonic condition. He considers the reptilian homologies to preponderate."

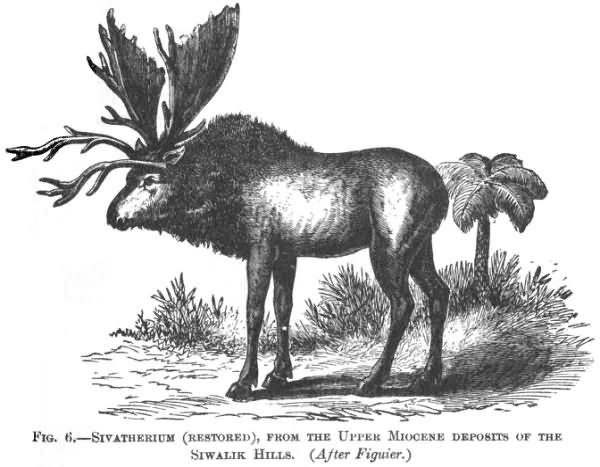

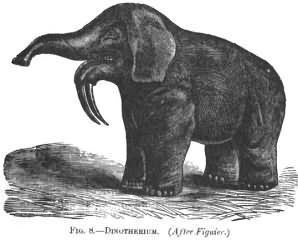

41:* A similar habit is ascribed by the Chinese to the mammoth and to the gigantic Sivatherium (Fig. 6, p. 39), a four-horned stag, which had the bulk of an elephant, and exceeded it in height. It was remarkable for being in some respects between the stags and the pachyderms. The Dinotherium (Fig. 8), which had a trunk like an elephant, and two inverted tusks, presented in its skull a mixture of the characteristics of the elephant, hippopotamus, tapir, and dugong. Its remains occur in the Miocene of Europe.