Secret Chambers and Hiding Places, by Allan Fea

CHAPTER IX

JAMES II.'S ESCAPES

We have spoken of the old houses associated with Charles II.'s escapes, let us see what history has to record of his unpopular brother James. The Stuarts seem to have been doomed, at one time or another, to evade their enemies by secret flight, and in some measure this may account for the romance always surrounding that ill-fated line of kings and queens.

James V. of Scotland was wont to amuse himself by donning a disguise, but his successors appear to have been doomed by fate to follow his example, not for recreation, but to preserve their lives.

Mary, Queen of Scots, upon one occasion had to impersonate a laundress. Her grandson and great-grandson both were forced to masquerade as servants, and her great-great-grandson Prince James Frederick Edward passed through France disguised as an abbá.

The escapades of his son the "Bonnie Prince" will require our attention presently; we will, therefore, for the moment confine our thoughts to James II.

With the surrender of Oxford the young Prince James found himself Fairfax's prisoner. His elder brother Charles had been more fortunate, having left the city shortly before for the western counties, and after effecting his escape to Scilly, he sought refuge in Jersey, whence he removed to the Hague. The Duke of Gloucester and the Princess Elizabeth already had been placed under the custody of the Earl of Northumberland at St. James's Palace, so the Duke of York was sent there also. This was in 1646. Some nine months elapsed, and James, after two ineffectual attempts to regain his liberty, eventually succeeded in the following manner.

Though prisoners, the royal children were permitted to amuse themselves within the walls of the palace much as they pleased, and among the juvenile games with which they passed away the time, "hide-and-seek" was first favourite. James, doubtless with an eye to the future, soon acquired a reputation as an expert hider, and his brother and sister and the playmates with whom they associated would frequently search the odd nooks and corners of the old mansion in vain for an hour at a stretch. It was, therefore, no extraordinary occurrence on the night of April 20th, 1647, that the Prince, after a prolonged search, was missing. The youngsters, more than usually perplexed, presently persuaded the adults of the prison establishment to join in the game, which, when their suspicions were aroused, they did in real earnest. But all in vain, and at length a messenger was despatched to Whitehall with the intelligence that James, Duke of York, had effected his escape. Everything was in a turmoil. Orders were hurriedly dispatched for all seaport towns to be on the alert, and every exit out of London was strictly watched; meanwhile, it is scarcely necessary to add, the young fugitive was well clear of the city, speeding on his way to the Continent.

The plot had been skilfully planned. A key, or rather a duplicate key, had given admittance through the gardens into St. James's Park, where the Royalist, though outwardly professed Parliamentarian, Colonel Bamfield was in readiness with a periwig and cloak to effect a speedy disguise. When at length the fugitive made his appearance, minus his shoes and coat, he was hurried into a coach and conveyed to the Strand by Salisbury House, where the two alighted, and passing down Ivy Lane, reached the river, and after James's disguise had been perfected, boat was taken to Lyon Quay in Lower Thames Street, where a barge lay in readiness to carry them down stream.

So far all went well, but on the way to Gravesend the master of the vessel, doubtless with a view to increasing his reward, raised some objections. The fugitive was now in female attire, and the objection was that nothing had been said about a woman coming aboard; but he was at length pacified, indeed ere long guessed the truth, for the Prince's lack of female decorum, as in the case of his grandson "the Bonnie Prince" nearly a century afterwards, made him guess how matters really stood. Beyond Gravesend the fugitives got aboard a Dutch vessel and were carried safely to Middleburg.

We will now shift the scene to Whitehall in the year 1688, when, after a brief reign of three years, betrayed and deserted on all sides, the unhappy Stuart king was contemplating his second flight out of England. The weather-cock that had been set up on the banqueting hall to show when the wind "blew Protestant" had duly recorded the dreaded approach of Dutch William, who now was steadily advancing towards the capital. On Tuesday, December 10th, soon after midnight, James left the Palace by way of Chiffinch's secret stairs of notorious fame, and disguised as the servant of Sir Edward Hales, with Ralph Sheldon—La Badie—a page, and Dick Smith, a groom, attending him, crossed the river to Lambeth, dropping the great seal in the water on the way, and took horse, avoiding the main roads, towards Farnborough and thence to Chislehurst. Leaving Maidstone to the south-west, a brief halt was made at Pennenden Heath for refreshment. The old inn, "the Woolpack," where the party stopped for their hurried repast, remains, at least in name, for the building itself has of late years been replaced by a modern structure. Crossing the Dover road, the party now directed their course towards Milton Creek, to the north-east of Sittingbourne, where a small fishing-craft lay in readiness, which had been chartered by Sir Edward Hales, whose seat at Tunstall[1] was close by.

[Footnote 1: The principal seat of the Hales, near Canterbury, is now occupied as a Jesuit College. The old manor house of Tunstall, Grove End Farm, presents both externally and internally many features of interest. The family was last represented by a maid lady who died a few years since.]

One or two old buildings in the desolate marsh district of Elmley, claim the distinction of having received a visit of the deposed monarch prior to the mishaps which were shortly to follow. King's Hill Farm, once a house of some importance, preserves this tradition, as does also an ancient cottage, in the last stage of decay, known as "Rats' Castle."

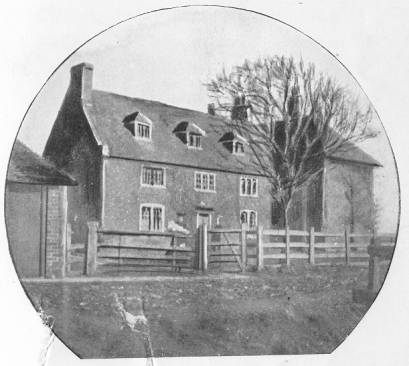

"RATS' CASTLE," ELMLEY, KENT

KING'S HILL FARM, ELMLEY, KENT

At Elmley Ferry, which crosses the river Swale, the king got aboard, but scarcely had the moorings been cast than further progress was arrested by a party of over-zealous fishermen on the look out for fugitive Jesuit priests. The story of the rough handling to which the poor king was subjected is a somewhat hackneyed school-book anecdote, but some interesting details have been handed down by one Captain Marsh, by James's natural son the Duke of Berwick, and by the Earl of Ailesbury.

From these accounts we gather that in the disturbance that ensued a blow was aimed at the King, but that a Canterbury innkeeper named Platt threw himself in the way and received the blow himself. It is recorded, to James II.'s credit, that when he was recognised and his stolen money and jewels offered back to him, he declined the former, desiring that his health might be drunk by the mob. Among the valuables were the King's watch, his coronation ring, and medals commemorating the births of his son the Chevalier St. George and of his brother Charles II.

The King was taken ashore at a spot called "the Stool," close to the little village of Oare, to the north-west of Faversham, to which town he was conveyed by coach, attended by a score of Kentish gentlemen on horseback. The royal prisoner was first carried to the "Queen's Arms Inn," which still exists under the name of the "Ship Hotel." From here he was taken to the mayor's house in Court Street (an old building recently pulled down to make way for a new brewery) and placed under a strict guard, and from the window of his prison the unfortunate King had to listen to the proclamation of the Prince of Orange, read by order of the mayor, who subsequently was rewarded for the zeal he displayed upon the occasion.

The hardships of the last twenty-four hours had told severely upon James. He was sick and feeble and weakened by profuse bleeding of the nose, to which he, like his brother Charles, was subject when unduly excited. Sir Edward Hales, in the meantime, was lodged in the old Court Hall (since partially rebuilt), whence he was removed to Maidstone gaol, and to the Tower.

Bishop Burnet was at Windsor with the Prince of Orange when two gentlemen arrived there from Faversham with the news of the King's capture. "They told me," he says, "of the accident at Faversham, and desired to know the Prince's pleasure upon it. I was affected with this dismal reverse of the fortunes of a great prince, more than I think fit to express. I went immediately to Bentinck and wakened him, and got him to go in to the Prince, and let him know what had happened, that some order might be presently given for the security of the King's person, and for taking him out of the hands of a rude multitude who said they would obey no orders but such as came from the Prince."

Upon receiving the news, William at once directed that his father-in-law should have his liberty, and that assistance should be sent down to him immediately; but by this time the story had reached the metropolis, and a hurried meeting of the Council directed the Earl of Feversham to go to the rescue with a company of Life Guards. The faithful Earl of Ailesbury also hastened to the King's assistance. In five hours he accomplished the journey from London to Faversham. So rapidly had the reports been circulated of supposed ravages of the Irish Papists, that when the Earl reached Rochester, the entire town was in a state of panic, and the alarmed inhabitants were busily engaged in demolishing the bridge to prevent the dreaded incursion.

But to return to James at Faversham. The mariners who had handled him so roughly now took his part—in addition to his property—and insisted upon sleeping in the adjoining room to that in which he was incarcerated, to protect him from further harm. Early on Saturday morning the Earl of Feversham made his appearance; and after some little hesitation on the King's side, he was at length persuaded to return to London. So he set out on horseback, breaking the journey at Rochester, where he slept on the Saturday night at Sir Richard Head's house. On the Sunday he rode on to Dartford, where he took coach to Southwark and Whitehall. A temporary reaction had now set in, and the cordial reception which greeted his reappearance revived his hopes and spirits. This reaction, however, was but short-lived, for no sooner had the poor King retired to the privacy of his bed-chamber at Whitehall Palace, than an imperious message from his son-in-law ordered him to remove without delay to Ham House, Petersham.

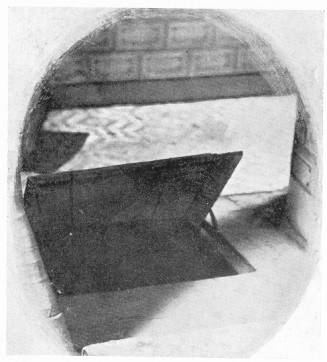

ENTRANCE TO SECRET PASSAGE, "ABDICATION HOUSE," ROCHESTER

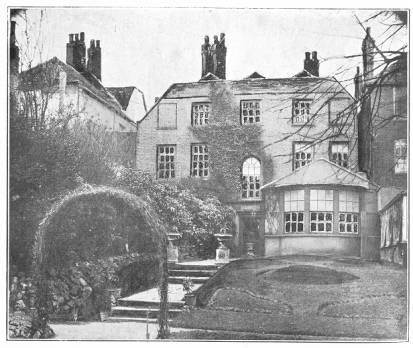

"ABDICATION HOUSE," ROCHESTER

James objected strongly to this; the place, he said, was damp and unfurnished (which, by the way, was not the case if we may judge from Evelyn, who visited the mansion not long before, when it was "furnished like a great Prince's"—indeed, the same furniture remains intact to this day), and a message was sent back that if he must quit Whitehall he would prefer to retire to Rochester, which wish was readily accorded him.

Index | Next: James II.s Escapes (continued)